Reducing Disaster Risks from Natural Hazards

Chapter 2 | Engaging Strategically in Countries Experiencing Disaster Risk

The World Bank has tripled its disaster risk reduction (DRR) support since fiscal year 2010, with a considerable expansion of DRR lending operations into new countries. The expansion of DRR is associated with the World Bank’s prioritization of climate change adaptation, the International Development Association’s special theme on climate change, the support of the Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery, and a conducive global authorizing environment for DRR.

The World Bank’s support for DRR has been highly relevant and focused on countries with the most serious natural hazards. The World Bank’s support often uses multiple and synergistic pillars of DRR engagement that include hazard identification, the development of resilient infrastructure, early-warning and preparedness activities, and disaster risk finance on occasion. DRR has been increasingly mainstreamed into sector operations. The World Bank has also shifted its focus from post-disaster response toward risk reduction and has built risk reduction into nearly all disaster response activities.

World Bank support for DRR has been comprehensive in International Development Association countries, including in low-income countries experiencing fragility, conflict, and violence, where it has addressed multiple pillars of DRR engagement through lending and nonlending activities.

However, there are coverage gaps in the Middle East and North Africa and in Europe and Central Asia, as well as across hazard types. Some hazard types that are rarer (tsunamis, volcanic eruptions) or less catastrophic (landslides) receive less attention in World Bank engagements than do others (floods, cyclones, droughts, and earthquakes).

Although Global Practices are increasingly mainstreaming DRR considerations into operations, the share of such operations remains low for the Agriculture and Food and Energy and Extractives Global Practices, and mainstreaming does not happen evenly across subsectors.

This chapter assesses the relevance of the World Bank’s engagement in countries experiencing disaster risk. First, it examines broad portfolio trends. Second, it uses global natural hazard data, disaggregated by hazard type, to identify overlaps and gaps with Systematic Country Diagnostics (SCDs) and lending and advisory portfolios (see appendix A for the methodology). Third, it uses portfolio data to assess the extent to which the World Bank has undertaken DRR in line with good practices (appendix A explains the source of good practices).

Portfolio Composition and Trends

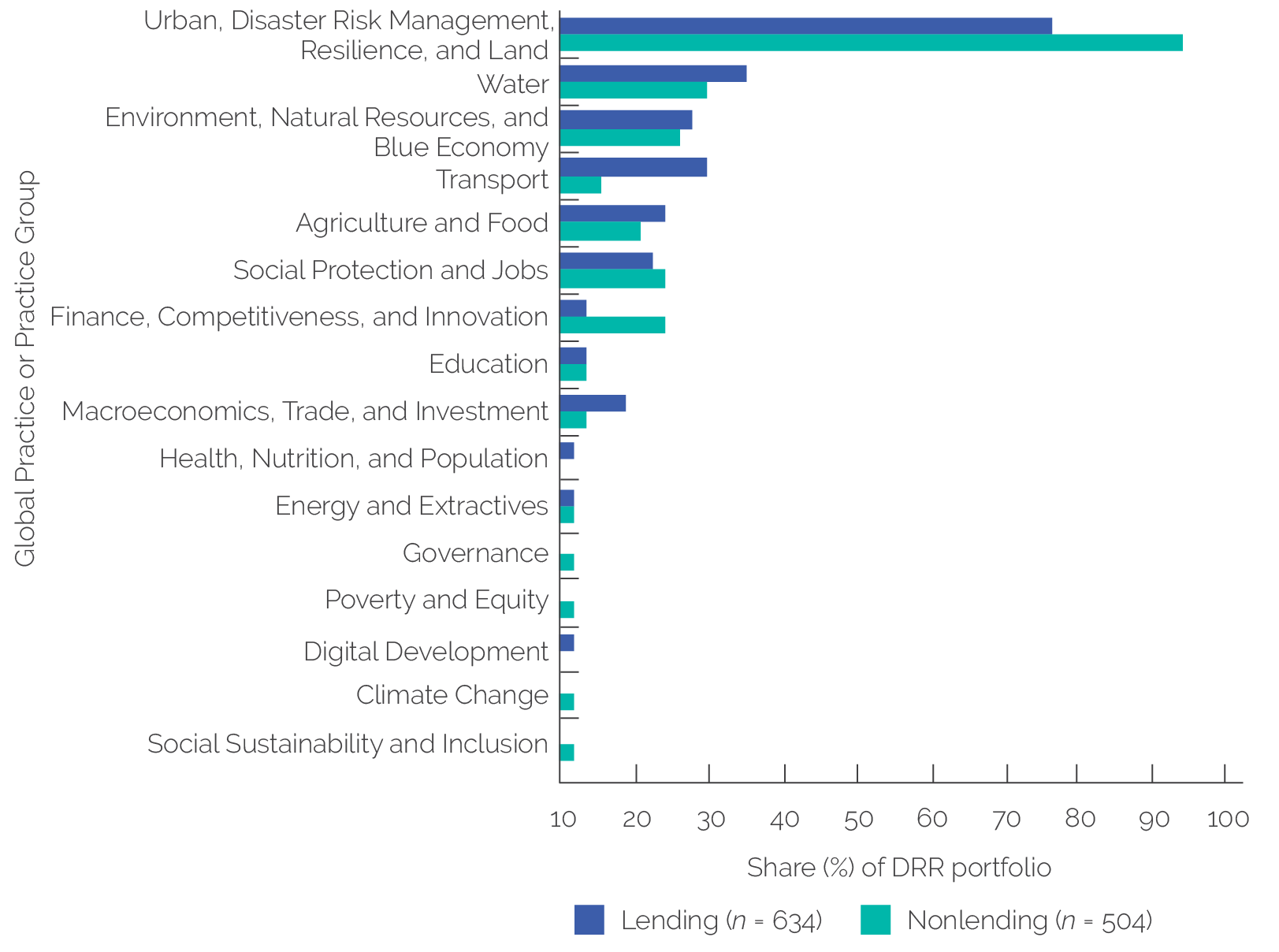

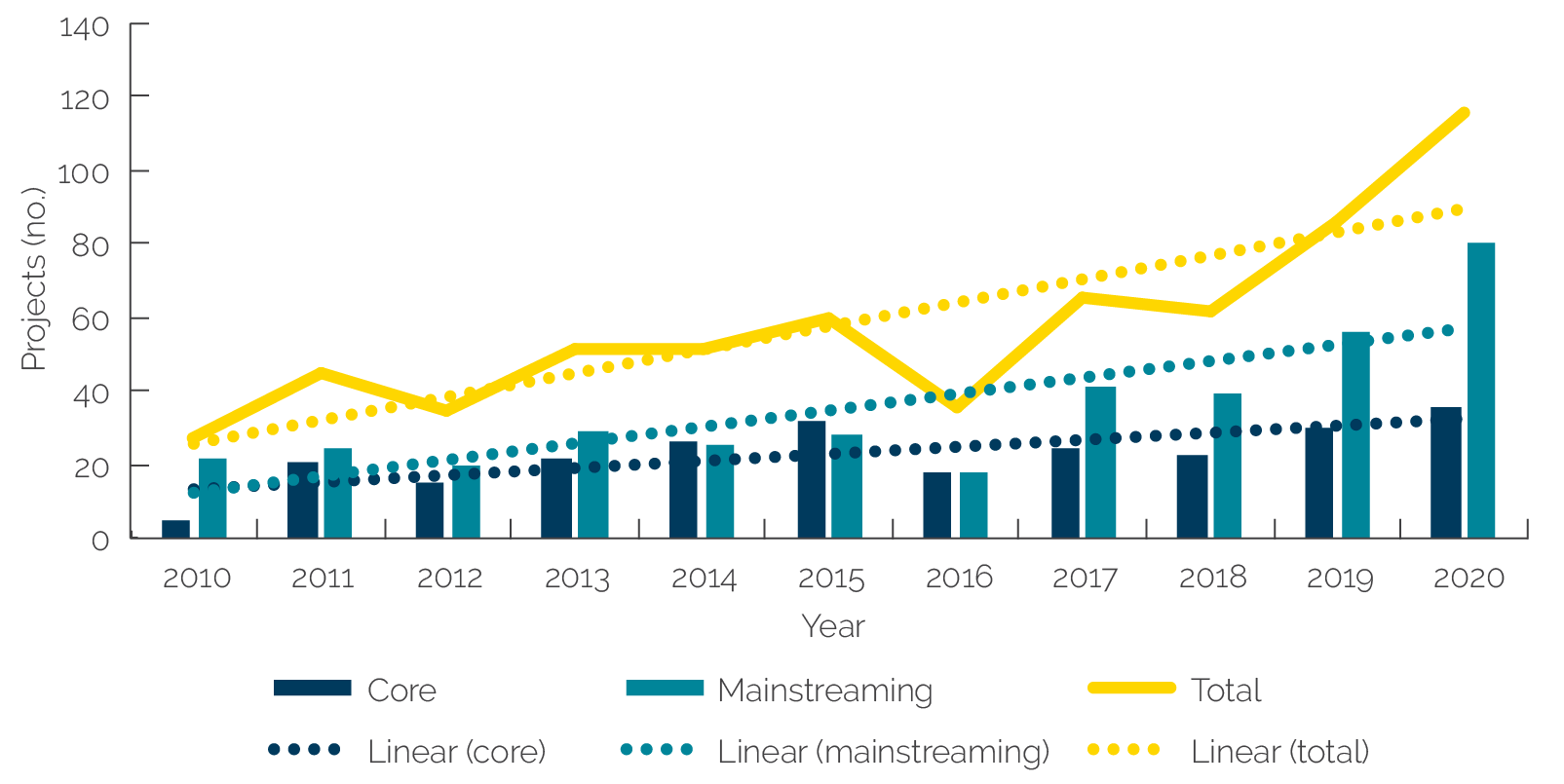

The World Bank has approved a large portfolio of DRR activities that help clients mitigate, prepare for, and recover from disasters caused by natural hazards. Between fiscal year (FY)10 and FY20, the World Bank approved 1,130 operations with DRR activities, including 634 lending and 504 nonlending products (420 country and 84 regional). Of these, 543 are investment project financing (IPF), 82 are development policy financing (DPF), and 9 are Program-for-Results financing. Projects mapped to the Urban, Disaster Risk Management, Resilience, and Land Global Practice (GP) make up almost half of the total portfolio, whereas Water GP and Environment, Natural Resources, and Blue Economy (ENB) GP projects make up roughly one-quarter of the portfolio; all three GPs have sizable amounts of both lending and nonlending projects (figure 2.1). The Social Protection and Jobs, Agriculture and Food, and Transport GPs account for much of the remaining lending projects, whereas the Finance, Competitiveness, and Innovation GP has a larger share of nonlending projects (8 percent) but a smaller share of lending ones (2 percent). GP mappings also do not capture the nature of cross-sectoral teams, such as the involvement of Finance, Competitiveness, and Innovation GP staff working on projects mapped to the Urban, Disaster Risk Management, Resilience, and Land GP. Both lending and nonlending activities support a range of DRR activities, including capacity building, policy reforms, hazard identification, resilient infrastructure, and protective works; disaster risk finance (for example, insurance); and hydrometeorological monitoring and EWSs, as well as community-preparedness activities. In the aftermath of disasters, these operations also support resilient recovery.

Figure 2.1. Disaster Risk Reduction Portfolio Composition, by Global Practice Share (FY10–20)

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: DRR = disaster risk reduction; FY = fiscal year.

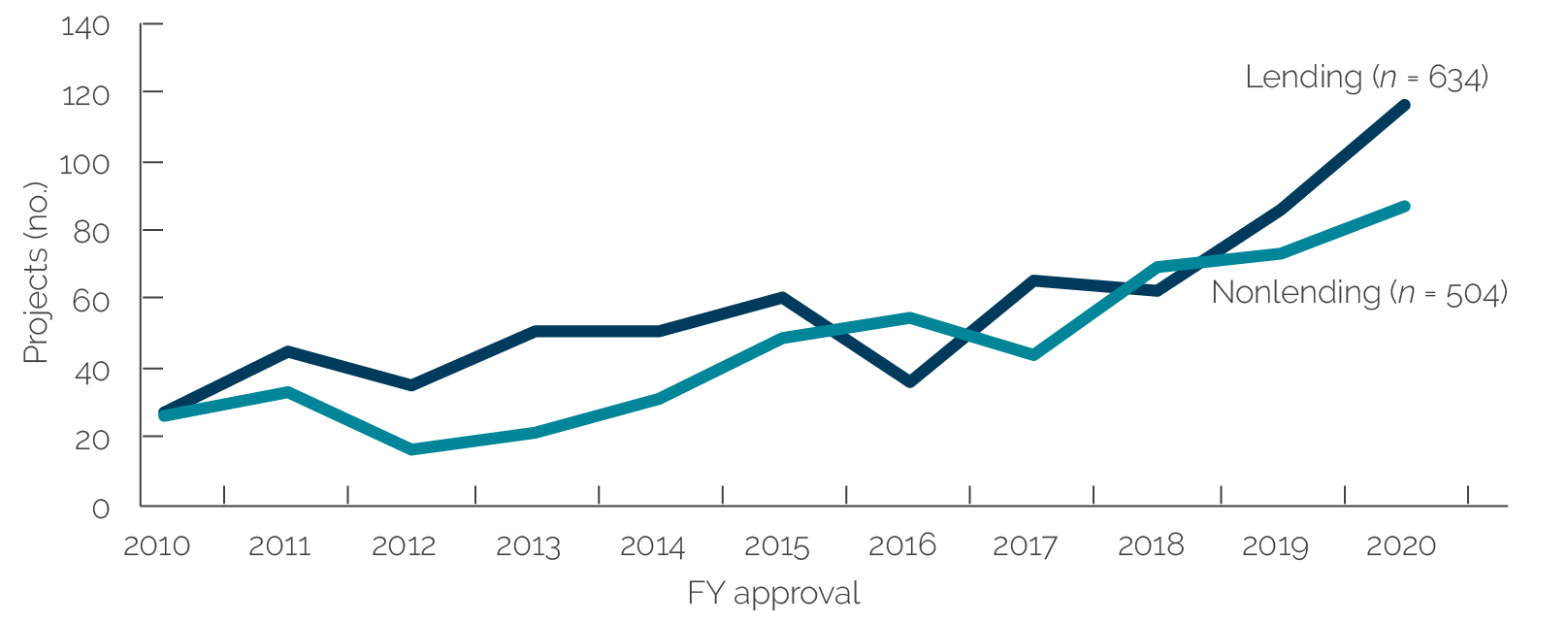

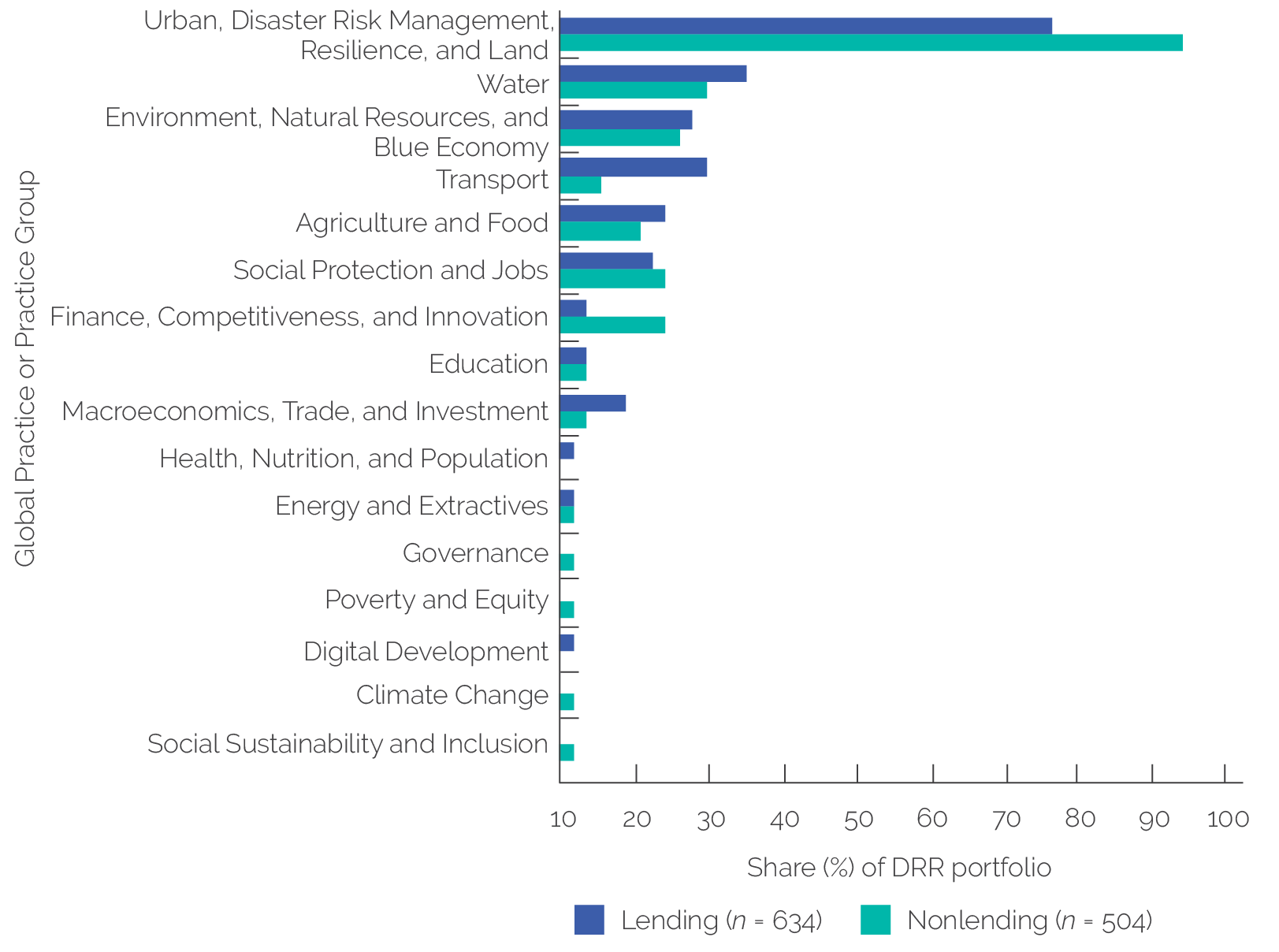

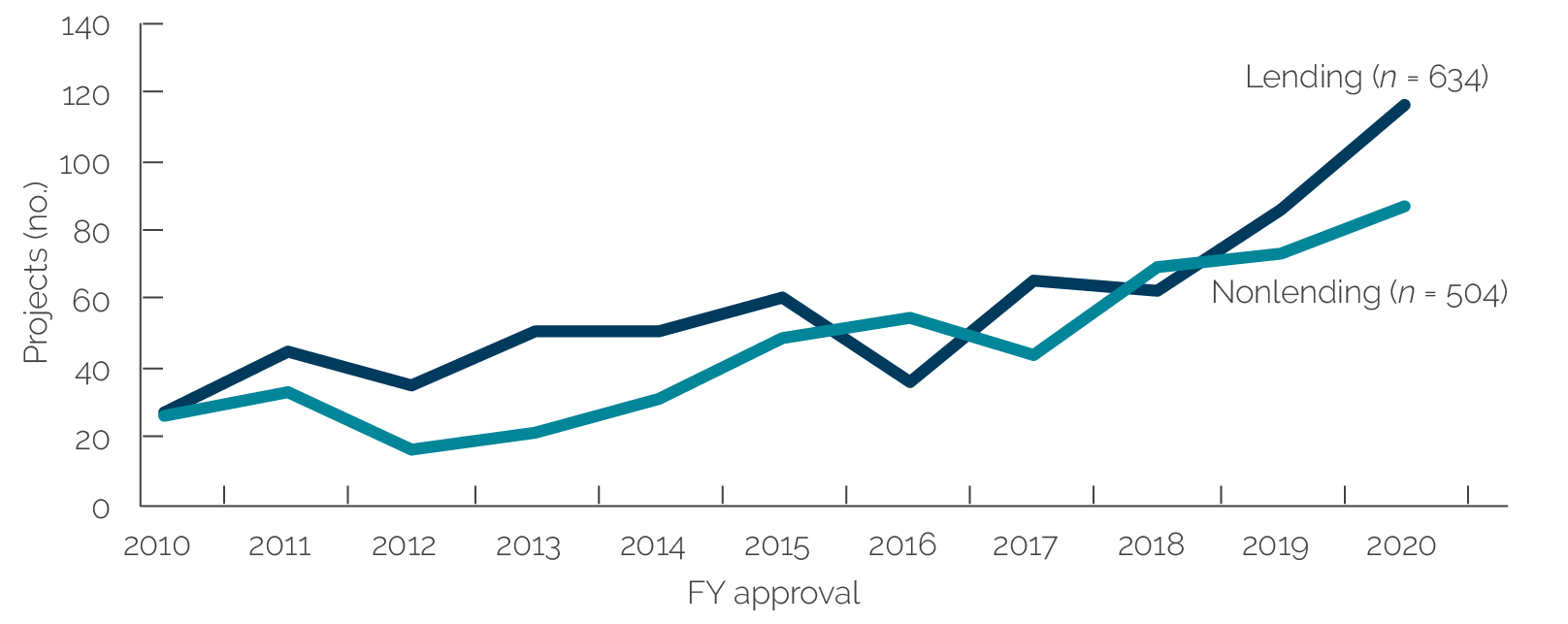

The World Bank has more than tripled its support for DRR over the evaluation period. DRR lending projects and nonlending activities have steadily increased during FY10–20 (figures 2.2 and 2.3). More than one-third of the DRR lending portfolio was approved in FY19–20. DRR nonlending has also grown steadily. The growth in DRR activities has accelerated since FY16.

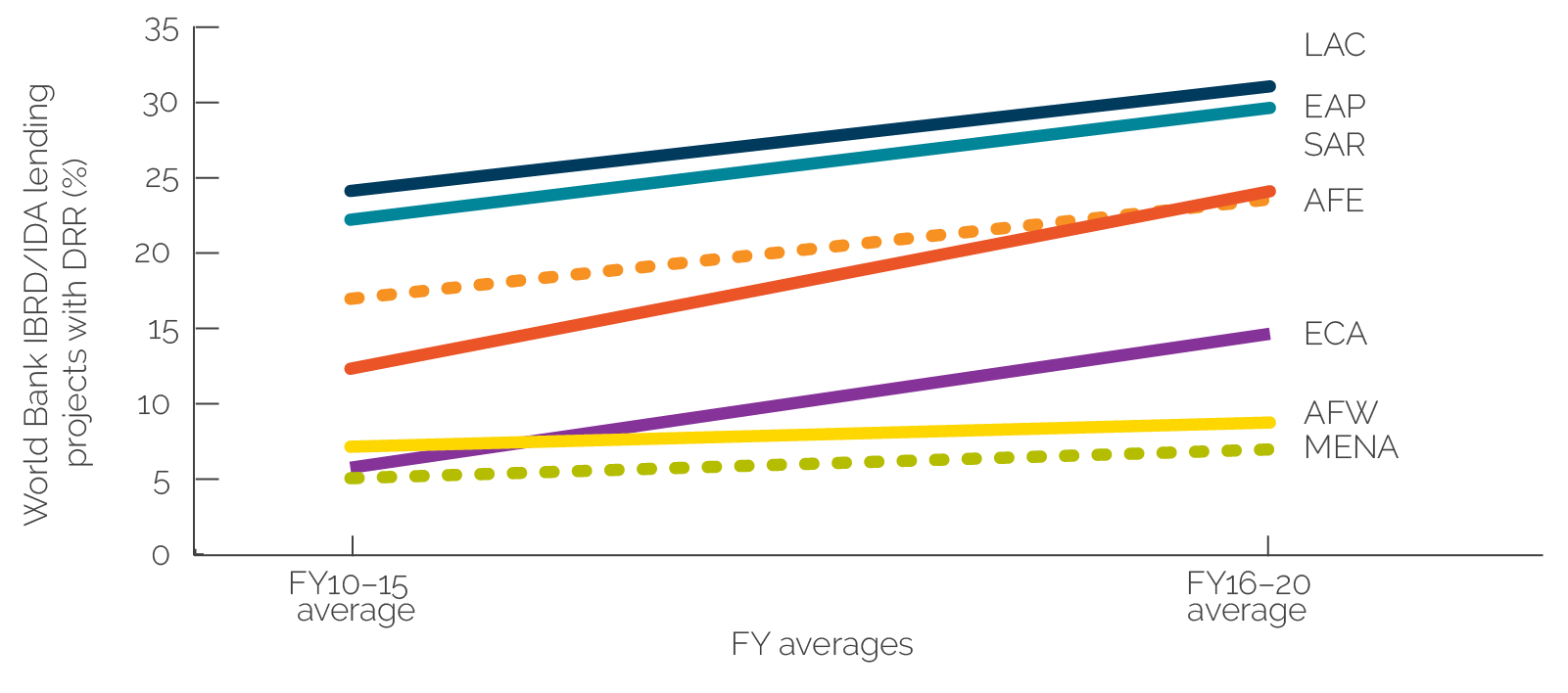

There has been a considerable expansion of DRR lending operations into many new countries where DRR lending historically has been absent. DRR lending activities were approved in 100 countries between FY16 and FY20, up from 75 countries in FY10–15. The share of newly approved DRR lending projects has increased across all Regions (see figure 2.3), with recent increases in West Africa, the Middle East and North Africa, and Europe and Central Asia, where DRR lending was sparse before. In West Africa, the slight growth of DRR is driven by the integration of DRR considerations into social safety nets and urban development, especially in coastal cities and for urban flooding. In the Middle East and North Africa, expansion is explained by the initiation of dedicated disaster risk management (DRM) programs (such as in Morocco) and the integration of DRR into urban development, including in wastewater management in West Bank and Gaza, housing in the Arab Republic of Egypt, and slum upgrading in Djibouti.

Figure 2.2. World Bank Nonlending and Lending Projects with Disaster Risk Reduction Activities (FY10–20)

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: FY = fiscal year.

Figure 2.3. Disaster Risk Reduction Lending Projects as a Share of All Projects, by Region (FY10–20)

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: AFE = Africa East; AFW = Africa West; DRR = disaster risk reduction; EAP = East Asia and Pacific; ECA = Europe and Central Asia; FY = fiscal year; IBRD = International Bank for Reconstruction and Development; IDA = International Development Association; LAC = Latin America and the Caribbean; MENA = Middle East and North Africa; SAR = South Asia.

The expansion of DRR support is associated with the World Bank’s prioritization of climate change adaptation, the special theme on climate change of the International Development Association (IDA), the support of the Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery (GFDRR), and a conducive international authorizing environment for DRR. The World Bank has made climate change a corporate priority since 2008 and has put greater emphasis on adaptation and resilience in its climate portfolio since the publication of the World Bank Group Climate Change Action Plan 2016–2020. Consistent with the corporate strategic directions, Country Management Units (CMUs) have identified and promoted projects that support climate adaptation, including through DRR engagements. IDA’s special theme on climate change, its emphasis on adaptation and disasters, and its core indicator on DRR have also encouraged corporate efforts to prioritize DRR in IDA countries. GFDRR support has played a major role in enabling growth of DRR by financing analytical work and technical assistance and developing a critical mass of disaster experts to support World Bank project teams. A supportive international authorizing environment for DRR associated with the Sendai Framework may have also played a role by generating demand from clients who were signatories to this framework. Greater interest in DRR from major donor countries influenced IDA priorities and provided trust fund resources, especially to GFDRR.

Strategic Alignment of the World Bank’s Disaster Risk Reduction Portfolio

This evaluation assesses the World Bank’s strategic DRR focus by determining whether it has primarily supported DRR in the countries where specific natural hazards are most serious. The evaluation team identified the hazard level for seven natural hazard types for the 138 countries that had at least one lending project, using global data from ThinkHazard!, a tool developed by GFDRR that indicates the likelihood of different natural hazards affecting areas (ranging from high to very low levels; see appendix A). Countries with high hazard levels are those where the likelihood of a hazard event of at least a specific magnitude exceeds a threshold probability, as defined in ThinkHazard! Subsequently, the team assessed the extent to which the World Bank identifies disaster risks in its SCDs and incorporates risk reduction in its lending and nonlending activities, as well as how this coverage differs across hazards and countries.

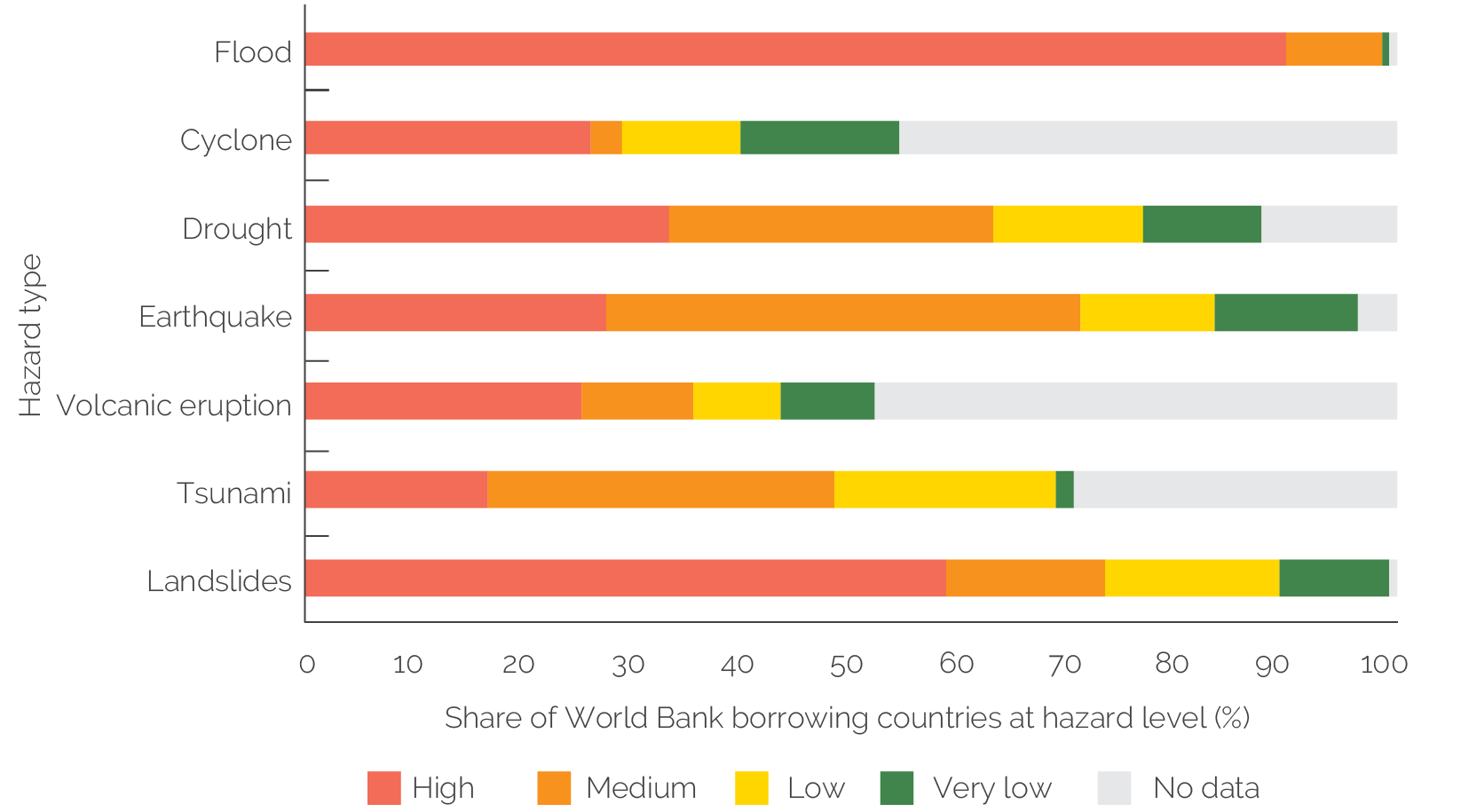

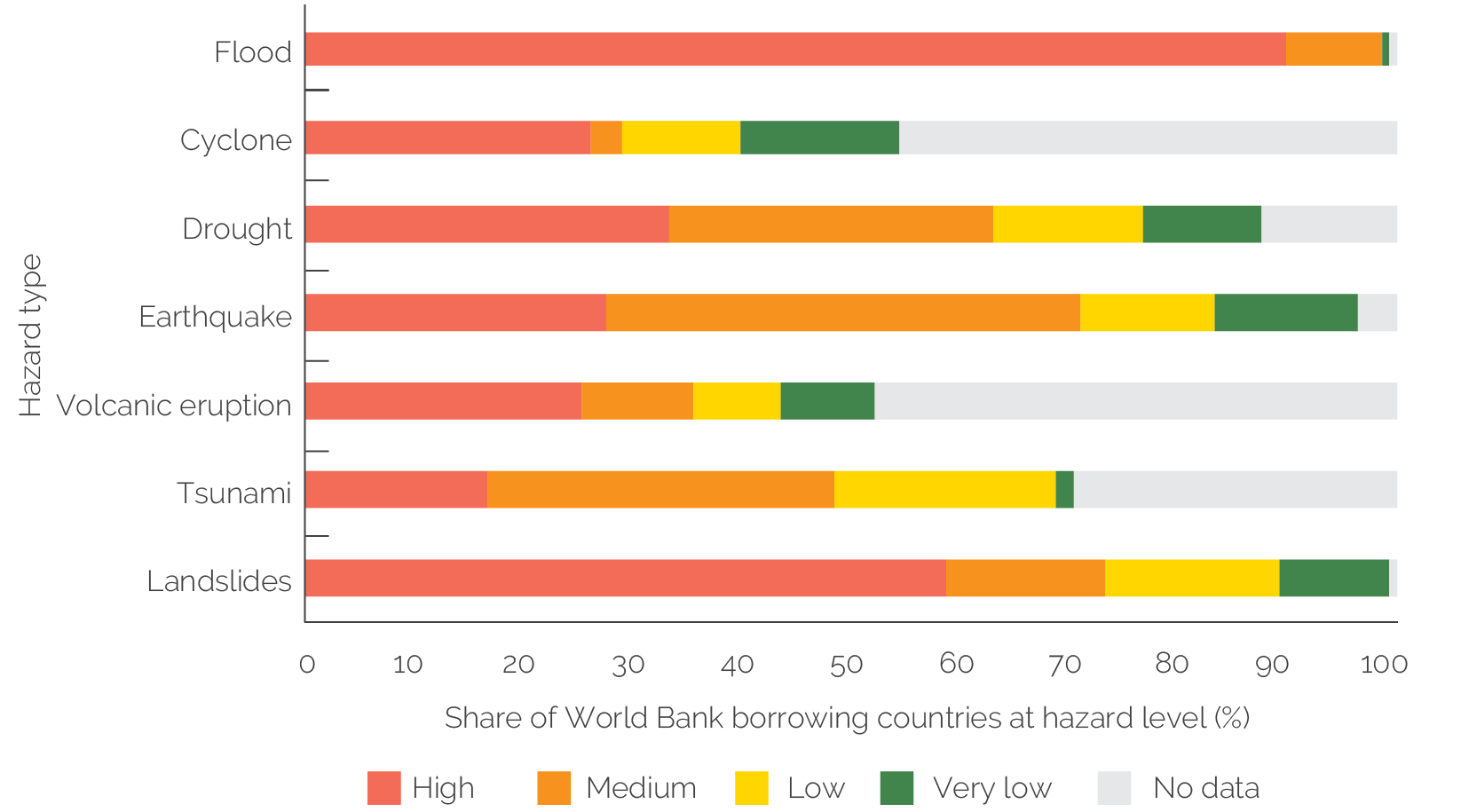

Nearly all World Bank client countries face serious natural hazards, especially flooding. Among all 138 borrowing countries, 133 are at high hazard levels for at least one hazard type (figure 2.4). High flood hazard levels are ubiquitous among borrowing countries, with 90 percent of countries having a high flood hazard level. High landslide hazard levels are also relatively common across World Bank borrowing countries (59 percent). Forty-six countries have a high drought hazard level; these countries are concentrated in Asia, the Sahara-Sahel belt, and western South America. Furthermore, 38 countries have a high hazard level for earthquakes; these countries are largely situated in the Pacific Ring of Fire and in Asia. High hazard levels for cyclones, volcanic eruptions, and tsunamis are comparatively less common.

Figure 2.4. Hazard Levels across Borrowing Countries, by Hazard Type

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: n = 138.

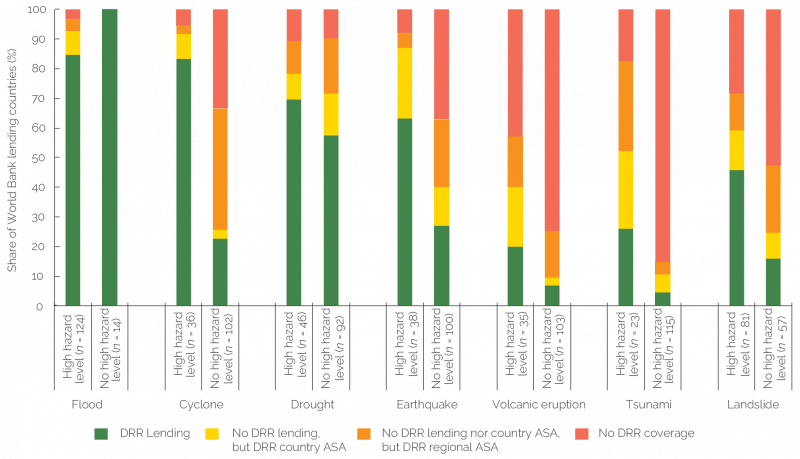

In general, the World Bank strategically focuses its DRR work on those countries where hazards are most serious. Across most hazard types, the World Bank provides hazard-specific DRR more often in countries with high hazard levels than in countries with lower hazard levels (figure 2.5).1 For flood and drought, the difference in country coverage is smallest, as these hazards are universally well covered. For cyclones, earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, tsunamis, and landslides, the targeting of countries with high hazard levels is much more pronounced. Countries with high hazard levels also tend to receive more lending and nonlending interventions in line with their specific hazard risks, as compared with countries with lower hazard levels.

The World Bank has supported flood, cyclone, drought, and earthquake risk reduction in most countries with serious hazards. The World Bank has supported risk reduction through lending activities in more than 80 percent of countries facing high hazard levels for floods and cyclones and more than 60 percent of countries facing high hazard levels for droughts and earthquakes. Furthermore, it has supported nonlending risk reduction activities in most of the remaining countries with high hazard levels. As a result, only between 3 percent and 11 percent of countries with high hazard levels have no lending or nonlending across these four hazard types. In contrast, World Bank lending support for risk reduction in countries with high hazard levels has been lower for volcanic eruptions (20 percent), tsunamis (26 percent), and landslides (46 percent). However, a substantial share of nonlending support for these three hazard types has been through regional activities. Across these three hazard types, between 17 percent and 43 percent of countries with high hazard levels have no coverage.

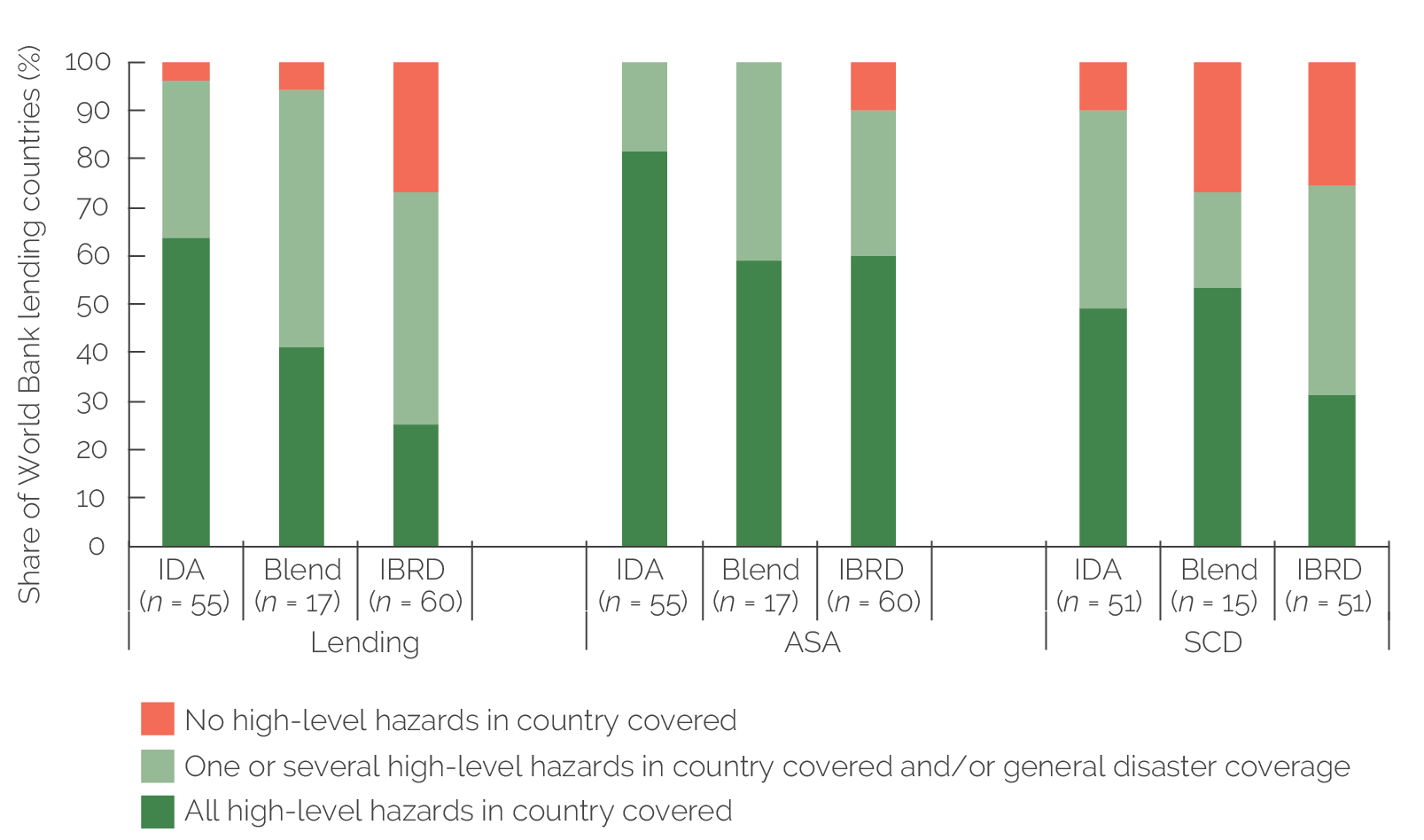

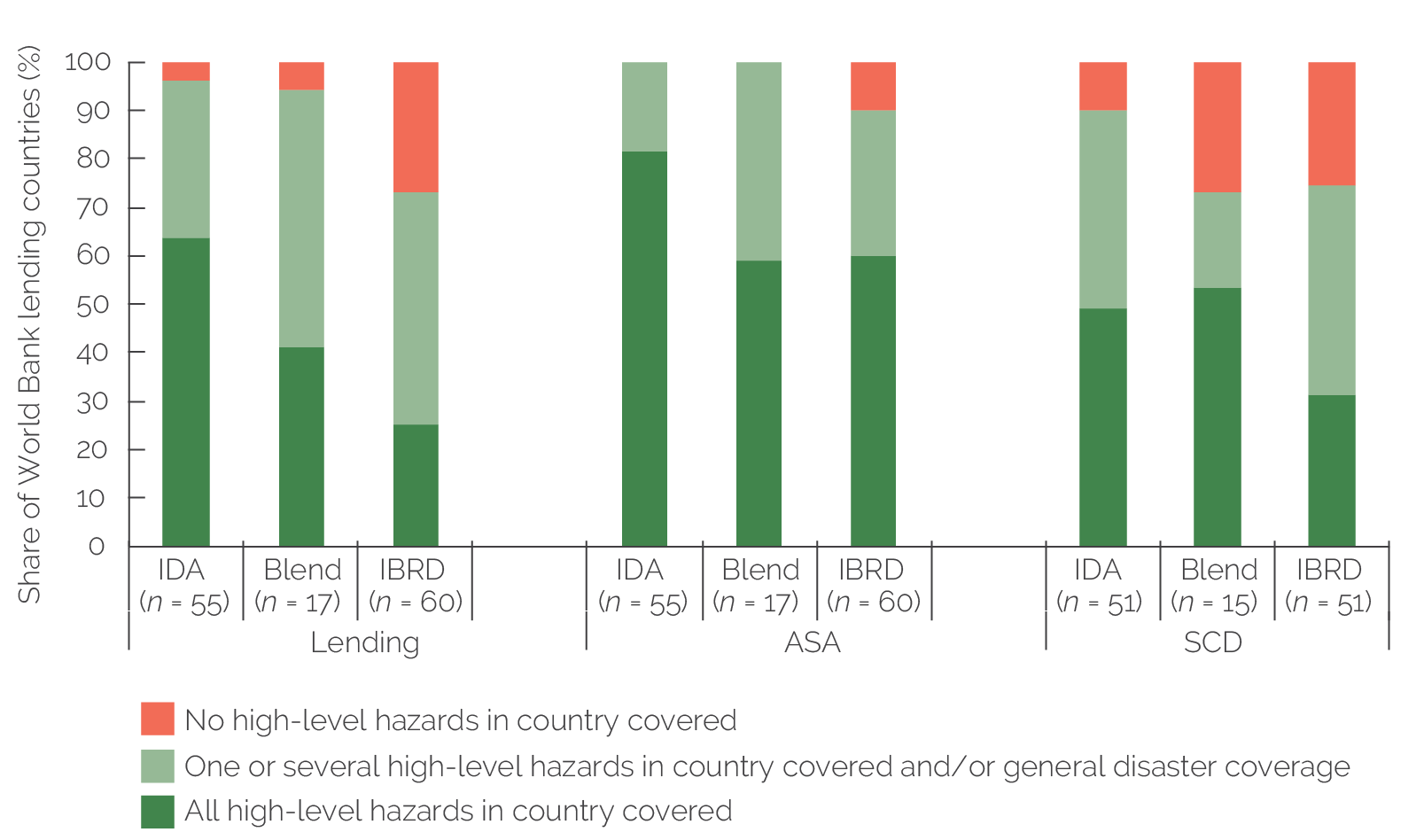

Serious hazards are being comprehensively addressed in IDA countries and in small island developing states (SIDS). In more than 60 percent of IDA countries with high hazard levels, the World Bank is providing lending operations that address all corresponding hazard types (figure 2.6). In almost all remaining high hazard–level IDA countries, the World Bank is addressing at least one or several high-level hazards through lending. There is even more comprehensive coverage of nonlending work in IDA countries: 82 percent of IDA countries are receiving nonlending support for all high-level hazards. Similarly, in 95 percent of SIDS with high hazard levels, the World Bank is providing lending operations that address at least one, several, or all corresponding hazard types. This share is lower but still high for fragility, conflict, and violence (FCV; mostly in IDA-FCV) countries (85 percent).

Figure 2.5. Hazard-Specific Disaster Risk Reduction Lending and Nonlending in Countries, by Hazard Type and Country Hazard Level (FY10–20)

Figure 2.5. Hazard-Specific Disaster Risk Reduction Lending and Nonlending in Countries, by Hazard Type and Country Hazard Level (FY10–20)

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: ASA = advisory services and analytics; DRR = disaster risk reduction; FY = fiscal year.

Figure 2.6. Extent of Disaster Risk Reduction Coverage for High-Level Hazards in Countries, by Lending Status (FY10–20)

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: ASA = advisory services and analytics; FY = fiscal year; IBRD = International Bank for Reconstruction and Development; IDA = International Development Association; SCD = Systematic Country Diagnostic.

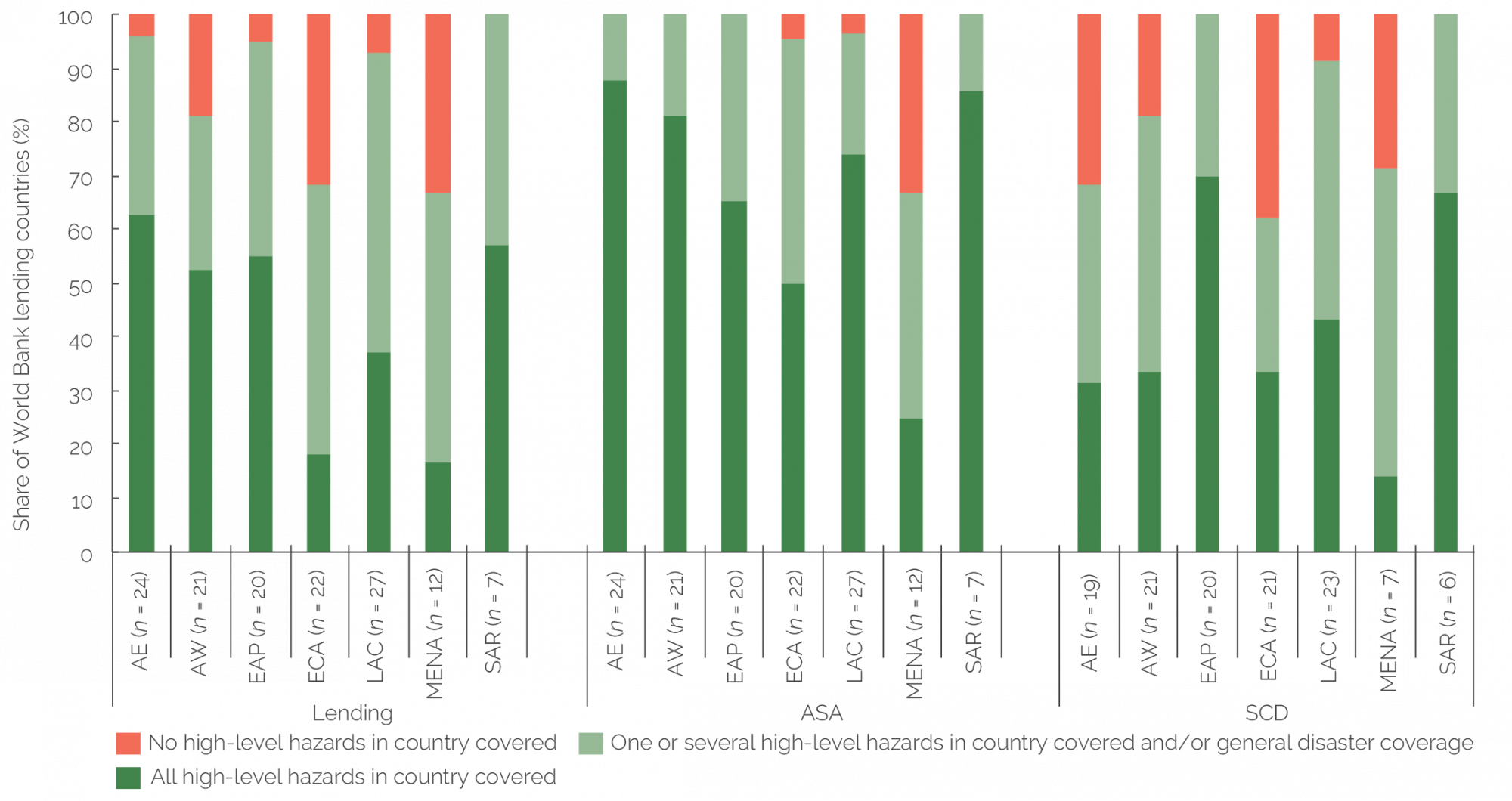

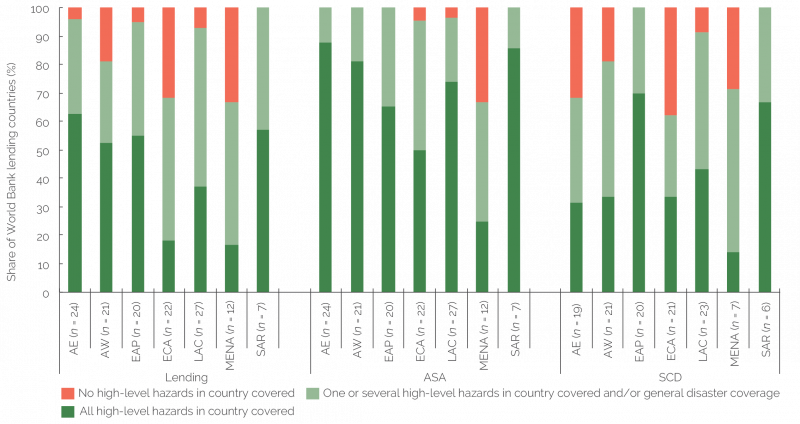

There are DRR coverage gaps for some serious hazards in the Middle East and North Africa and Europe and Central Asia. These gaps are shown in figure 2.7, whereas box 2.1 explains potential reasons for these gaps. In the Middle East and North Africa, infrastructure investments in Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Tunisia, and the Republic of Yemen have not incorporated flood or drought risk reduction elements, even though these countries face high hazard levels for floods and drought. In Europe and Central Asia, countries with high flood hazard levels have not incorporated flood prevention measures into their infrastructure lending in Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Ukraine. Countries in Europe and Central Asia with high seismic risks—Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia—have not incorporated seismic risk activities into their infrastructure investments (whereas seismic risks have been covered by lending in the Kyrgyz Republic, Tajikistan, and Türkiye). It is also noteworthy that the World Bank has only supported disaster risk finance and no other elements of DRR in some countries in Europe and Central Asia with high hazard levels—Albania, Kazakhstan, and North Macedonia.

Figure 2.7. Extent of Disaster Risk Reduction Coverage for High-Level Hazards in Countries, by Region (FY10–20)

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: AE = Africa East; ASA = advisory services and analytics; AW = Africa West; EAP = East Asia and Pacific; ECA = Europe and Central Asia; FY = fiscal year; LAC = Latin America and the Caribbean; MENA = Middle East and North Africa; SAR = South Asia; SCD = Systematic Country Diagnostic.

In Europe and Central Asia, and to a lesser extent in the Middle East and North Africa, nonlending activities were used to supplement a lack of investment demand. In Middle East and North Africa countries where there is no flood-specific DRR lending, the World Bank provided a few important pieces of analytical work, including one regional advisory services and analytics (ASA) on water security; an ASA on disaster resilience in the agricultural sector in Jordan and Lebanon; climate and disaster studies in Tunisia; and a DRR training exercise in the Republic of Yemen, which was held before the current war. In countries in Europe and Central Asia with high earthquake hazard levels, the World Bank helped catalog at-risk schools in Armenia and integrated DRR into Azerbaijan’s housing strategy. For Europe and Central Asia countries with high flood hazard levels, the World Bank integrated DRR into urban planning and Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM) technical assistance in Armenia and Croatia and provided ASA on flash floods in Georgia. The World Bank has also provided Europe and Central Asia with regional ASA focused on broad DRR awareness raising.

Box 2.1. Reasons for Disaster Risk Reduction Coverage Gaps in the Middle East and North Africa and Europe and Central Asia Regions

Several factors may explain lower coverage for disaster risk reduction (DRR) in the Europe and Central Asia and Middle East and North Africa Regions. Both Regions are predominantly made up of International Bank for Reconstruction and Development clients, where the borrowing costs for DRR are sometimes seen to be high. In the Middle East and North Africa, there is a difference between the gradual uptake of DRR actions in the Maghreb—especially in Morocco, where technical support has underpinned DRR policy reforms—and the conflict-affected countries in the region where there has been modest to no uptake of DRR, in part because conflict and governance issues have been higher priorities than DRR in World Bank engagements. The Middle East and North Africa Region has also received less financing from the Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery (only 4 percent of this support over 2010–20) in comparison with other Regions, a factor that may explain the dearth of DRR analytical work there. The Europe and Central Asia Region has several small countries with a limited International Bank for Reconstruction and Development envelope that constrains

the number of sectors in which the World Bank can engage. Other regions with small countries are eligible for International Development Association support, including under the broader International Development Association eligibility for small states. European Union (includes potential) candidates have been more motivated to borrow for flood prevention than other hazards because the European Union has a flood prevention directive with which members must comply, but not a directive for any other hazard.

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

In general, SCDs in countries facing serious natural hazards adequately diagnose and discuss corresponding disaster risks, and lending for DRR is more common in countries with such SCDs. About two out of five SCDs adequately cover all high-level hazards in the country, while another two out of five adequately cover at least one or more high-level hazards (see appendix A for assessment criteria). Only 3 percent of SCDs fully lack DRR analysis and content. However, the depth of risk analysis and DRR content varies widely across SCDs: from SCDs that only list the hazards and refer to isolated DRR actions within sections on climate resilience to SCDs with disaster risk maps and integrated DRR strategies in dedicated sections. Furthermore, SCDs provide (i) higher coverage for floods, cyclones, earthquakes, and droughts (69 to 79 percent) compared with tsunamis, volcanic eruptions, and landslides (47 to 50 percent); (ii) higher coverage in IDA countries (figure 2.6); and (iii) lower coverage in Europe and Central Asia and the Middle East and North Africa (figure 2.7). In this sense, lending, nonlending, and SCD patterns are similar. Adequate coverage for high-level hazards in SCDs is associated with higher lending coverage for the corresponding hazard types (that is, positive correlation across all hazard types except drought).

Aligning Disaster Risk Reduction Support with Good Practices

This section of the evaluation examines whether the World Bank has evolved its approach to DRR in line with stated good practices. These good practices are derived from the World Bank’s report to the Board of Executive Directors, Mainstreaming Disaster Risk Management in World Bank Group Operations (published in 2014, 2016, 2018, and 2020). These good practices include (i) the pursuit of integrated approaches, (ii) a focus on predisaster vulnerability reduction, (iii) the mainstreaming of DRR considerations in sectors, and (iv) appropriate use of nature-based solutions (NBSs).

Integrated Approaches

The World Bank and external frameworks cite the need for “integrated approaches” to achieve effective DRR. Integrated approaches use multiple and synergistic pillars of engagement to help clients mitigate disaster risk and are expected to be more effective than partial approaches. The evaluation classifies these approaches into four pillars, adapted from the World Bank’s pillars and based on the Sendai Framework: (i) risk identification; (ii) risk reduction activities, especially resilient infrastructure and assets (including resilient reconstruction in post-disaster situations); (iii) preparedness activities, especially support for EWSs; and (iv) financial protection. To assess whether the World Bank is pursuing integrated approaches, the evaluation categorized the lending data in line with these pillars and analyzed the extent of country engagement on multiple pillars.

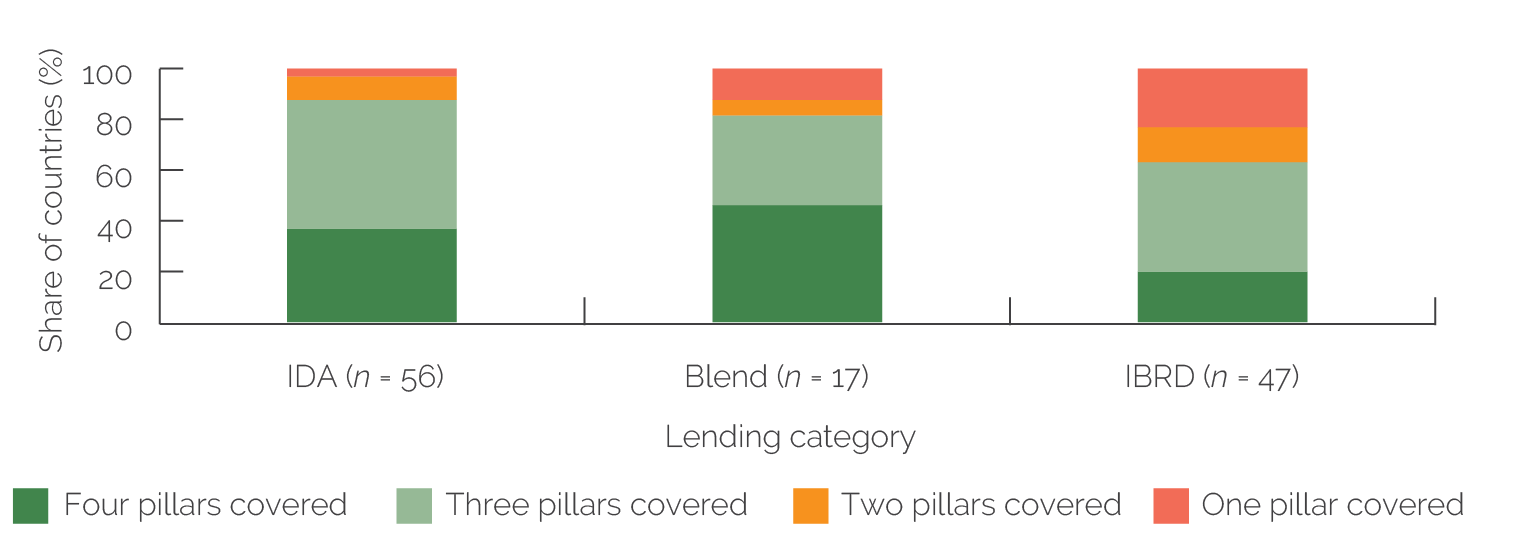

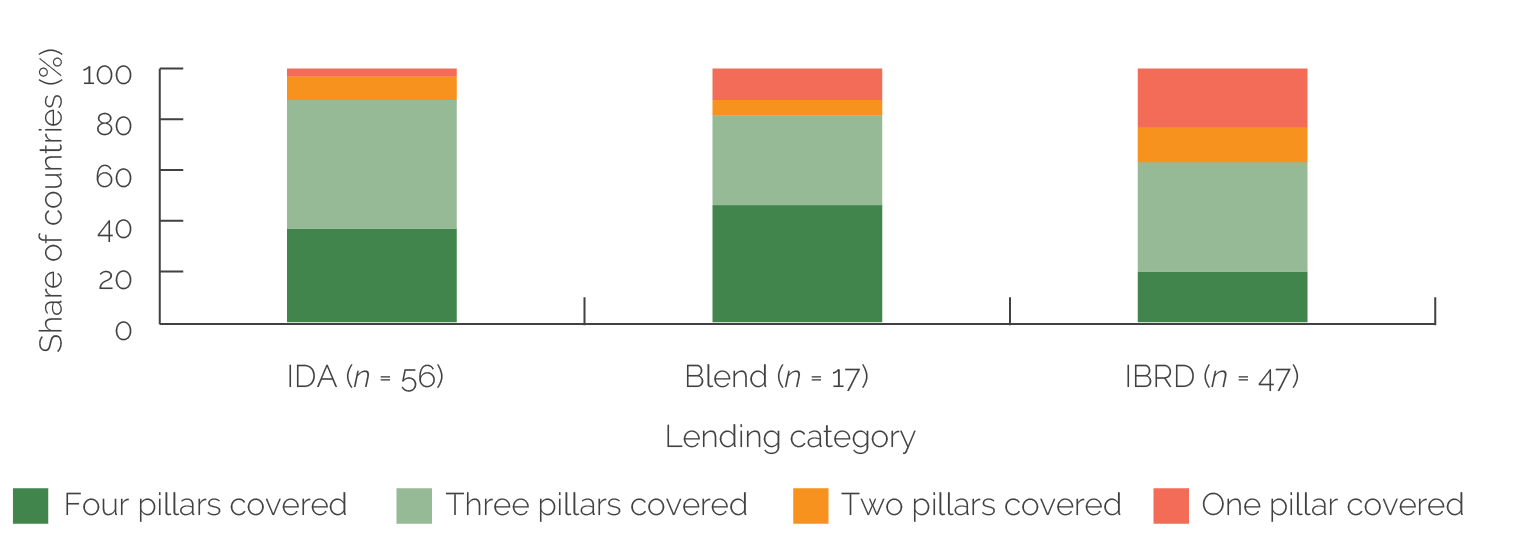

The World Bank pursued at least three pillars of support in about 80 percent of countries that received DRR lending. Fifty-five countries received a combination of three engagement pillars (45 percent of countries that received DRR lending), whereas 39 countries received all four pillars (32 percent). Of countries that received three pillars, most (84 percent) received support for hazard risk identification, resilient infrastructure, and early-warning and preparedness activities. Countries with four pillars also received support for financial protection. All but five countries that received support for three or more pillars had more than one DRR lending project.

In IDA countries, the World Bank is providing strong coverage of serious hazards and often addresses these hazards through multiple pillars of engagement, including in FCV countries. Eighty-eight percent of IDA countries with DRR lending had three or four DRR pillars (figure 2.8). Combined with the fact that most IDA countries with high hazard levels had lending that addressed all corresponding hazard types (see previous section on strategic alignment), this analysis finds that IDA is well covered. The World Bank also supported three or four pillars in 78 percent of FCV countries, most of which were IDA countries as well.

World Bank support for DRR is comparatively less integrated in International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD) countries, including in IBRD SIDS. Although 64 percent of IBRD countries engaged in three or four DRR pillars (figure 2.8), several countries (23 percent of all IBRD countries with DRR lending) had just one pillar, either for financial protection (including in Albania, Antigua and Barbuda, Costa Rica, Kazakhstan, North Macedonia, and Trinidad and Tobago) or for resilient infrastructure (as in Croatia, Ecuador, Palau, and Uruguay). Overall, 40 percent of IBRD SIDS had only one or two DRR pillars, compared with 18 percent of IDA SIDS that had two or fewer.

Figure 2.8. Extent of Disaster Risk Reduction Coverage across Country Lending Categories

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: Colors show the number of disaster risk reduction pillars supported in each country. IBRD = International Bank for Reconstruction and Development; IDA = International Development Association.

The World Bank provided less integrated DRR support to the Europe and Central Asia and Middle East and North Africa Regions, which are also the Regions least likely to include DRR lending for high-level hazards. The World Bank has provided three or more pillars to all countries receiving DRR lending in East Africa and to between 75 and 88 percent of countries in the East Asia and Pacific, Latin America and the Caribbean, Western and Central Africa, and South Asia Regions. However, only 50 percent of Middle East and North Africa countries and 59 percent of Europe and Central Asia countries receiving DRR lending had three or more pillars of DRR support.

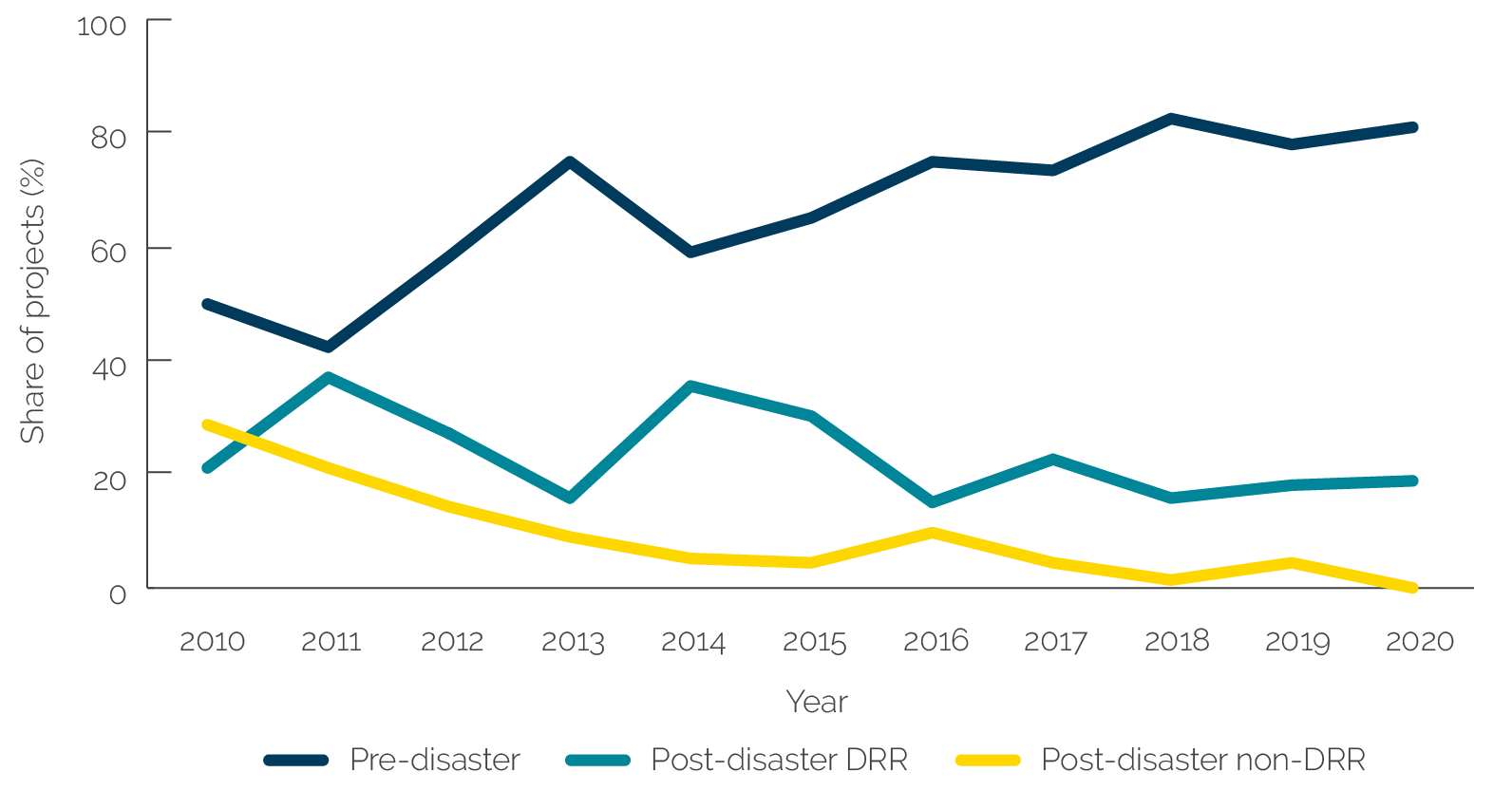

Pre- and Post-Disaster Risk Reduction Assistance

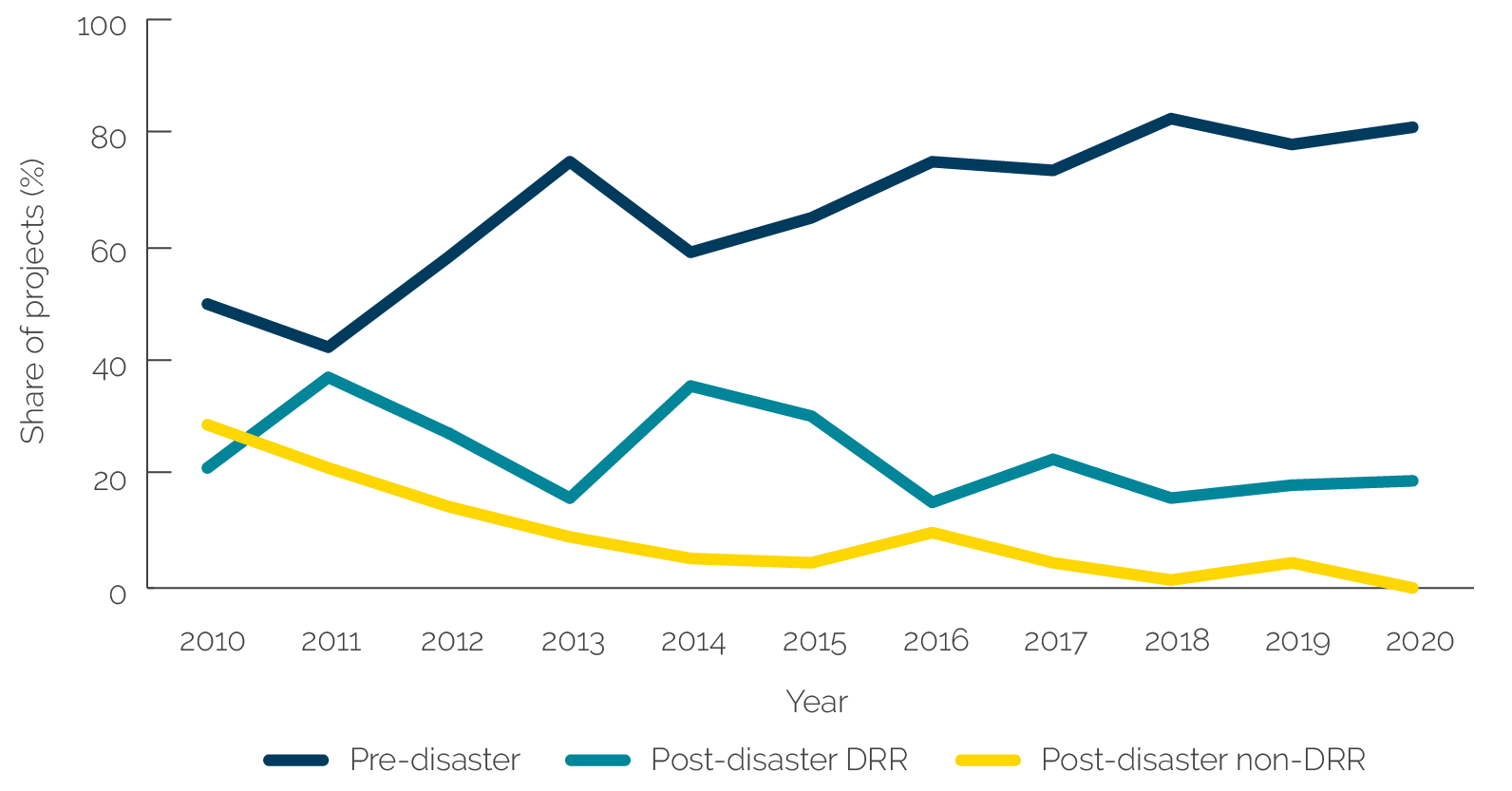

There is an increasing share of lending projects that support predisaster DRR activities as compared with post-disaster activities. Good practice on DRR emphasizes the importance of ex ante actions to reduce exposure and vulnerability. The share of World Bank DRR projects that engage in predisaster activities, compared with post-disaster ones, rose from 50 to 81 percent between FY10 and FY20 (figure 2.9). Moreover, the share of projects supporting disaster response without DRR elements declined from 29 to 0 percent between FY10 and FY20. Although there will likely always be a need for disaster response projects, the number of these projects that do not include risk reduction elements should go to zero over time.

Figure 2.9. Share of Pre- and Post-Disaster Risk Reduction Projects, by Type (FY10–20)

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: DRR = disaster risk reduction; FY = fiscal year.

Mainstreaming Disaster Risk Reduction into Sectors

The number of mainstreamed DRR projects has quadrupled. “Mainstreaming” refers to the integration of DRR elements into sector operations that have non-DRR aims. “Core” DRR projects have an explicit DRR development objective, theory, and activities. Most DRR projects are mainstreamed (60 percent), meaning they are sector operations that contain DRR elements. Both core and mainstreamed projects have increased over time, but mainstreamed projects have increased at a higher rate, from 22 projects in FY10 to 80 in FY20 (figure 2.10).

Figure 2.10. Share of Core versus Mainstreamed Disaster Risk Reduction Projects (FY10–20)

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: n = 634. FY = fiscal year.

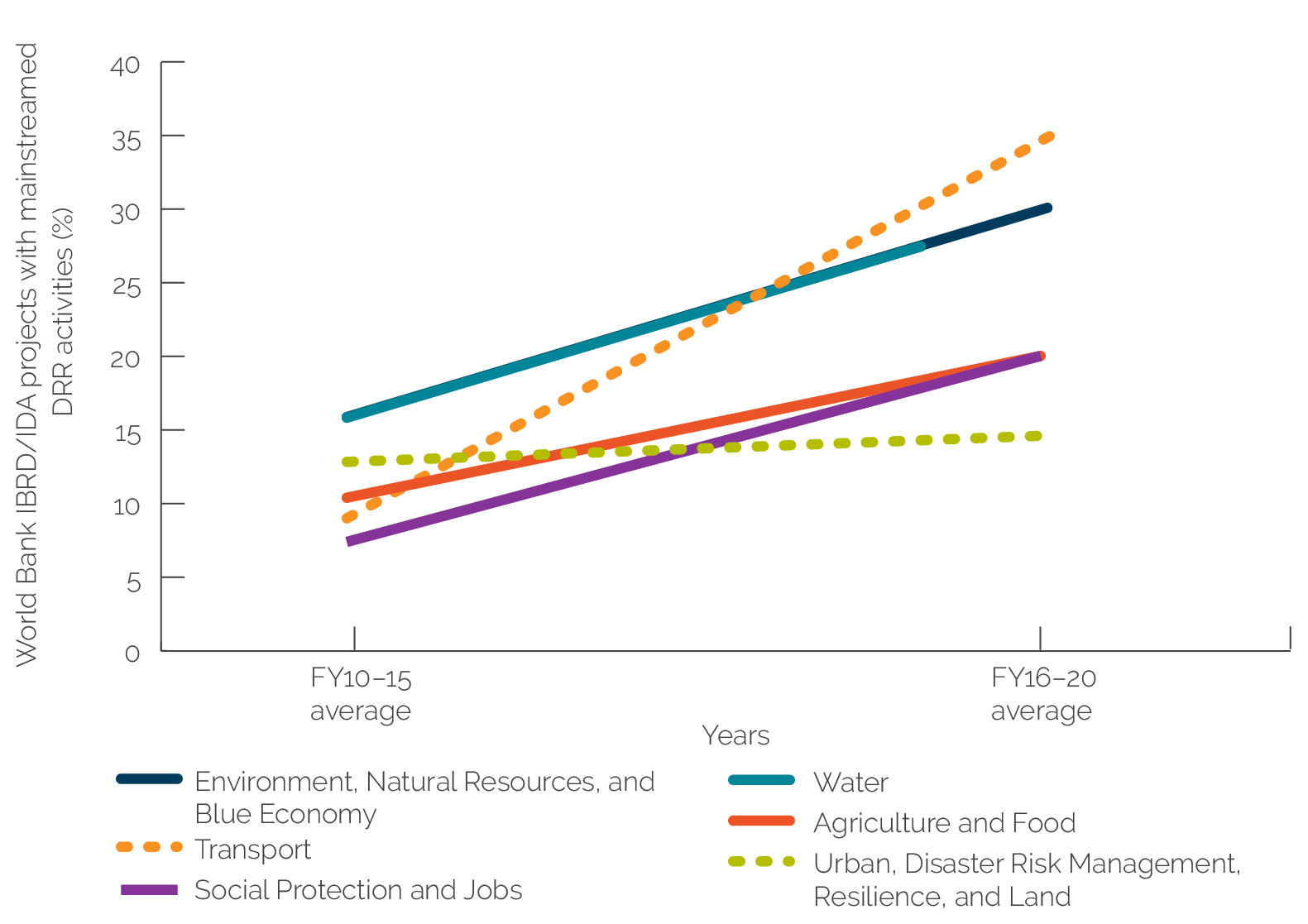

DRR has been increasingly mainstreamed into sector operations across all key GPs; many GPs, however, are starting from a low base. The Water GP and the ENB GP have nearly doubled their share of operations that include mainstreamed DRR activities during the evaluation period (figure 2.11). The Agriculture and Food GP doubled, the Social Protection and Jobs GP nearly tripled, and the Transport GP quadrupled their shares of projects with mainstreamed DRR; however, these GPs started from a very low base (figure 2.11). The share of mainstreamed projects in the Urban, Disaster Risk Management, Resilience, and Land GP—the GP primarily supporting core operations (70 percent of its DRR operations are core)—stayed the same, at just below 15 percent. There were only six projects in the Energy and Extractives GP with DRR activities. The DRR elements of these projects focused on reducing disruption from disasters and improving disaster preparedness. For example, some renewable energy projects sought to improve resilience through enhanced siting and by financing protective works. (Note, however, that dam safety projects were not included in the evaluation scope.)

Figure 2.11. Share of World Bank Projects with Mainstreamed Disaster Risk Reduction Activities (excludes core disaster risk reduction projects)

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: The Energy and Extractives Global Practice is excluded, as only 1–2 percent of projects had mainstreamed DRR. DRR = disaster risk reduction; FY = fiscal year; IBRD = International Bank for Reconstruction and Development; IDA = International Development Association.

DRR activities are increasingly being mainstreamed into water sector operations across countries of different types and through multiple subsector activities. The share of all Water GP lending operations with mainstreamed DRR activities rose from 16 to 27 percent between FY10 and FY15 and between FY16 and FY20 in 39 countries—of which 50 percent are IDA countries, 15 percent are Blend, and 35 percent are IBRD countries—while the share of core DRR projects remained the same (6–7 percent). There has been consistent attention to DRR in IWRM activities, a tripling of DRR activities in water supply and sanitation activities, and an introduction of DRR considerations into wastewater management since 2015. The increased mainstreaming of DRR in Water GP operations occurred alongside the launch in 2017 of the World Bank’s Water Security Diagnostic Initiative, which supported a broad shift in relation to water systems thinking. During the second half of the evaluation, project objectives and themes were more focused on water security, sustainable supply, reduced water loss, and efficiency in water systems.

The ENB GP is mainstreaming DRR considerations through its climate and green growth policy agenda, sustainable land management, and, increasingly, coastal and basin operations. The share of all ENB GP lending operations with mainstreamed DRR activities rose from 16 to 29 percent between FY10 and FY15 and between FY16 and FY20 in 27 countries—of which 56 percent are IDA countries, 4 percent are Blend, and 40 percent are IBRD countries—while the share of core DRR projects has remained steady at approximately 10 percent during both periods. One-fifth of this portfolio are development policy operations (DPOs) that support climate and disaster resilience. The shift includes increased focus, although small in project numbers, on support for coastal and marine management and the introduction of climate adaptation and resilience projects with DRR activities.

The World Bank is significantly expanding its support to strengthen disaster preparedness by mainstreaming DRR considerations in its adaptive social protection programs. Adaptive social protection programs are flexible programs that can protect poor households from climate and disaster shocks before they occur, with the help of predictable transfers, the building of disaster-resilient community assets, skills-building programs, and the scaling of these programs, especially by providing cash transfers in the face of extreme events. These projects recognize the role that governments need to play in building a shock-responsive social protection system and improving household resilience. The share of Social Protection and Jobs DRR mainstreamed lending projects rose from 7 to 20 percent between FY10 and FY15 and between FY16 and FY20, with new projects in 26 countries, mostly in Africa. The World Bank also tripled the amount of Social Protection and Jobs DRR country analytical work between FY10 and FY20.

The Agriculture and Food GP has doubled the share of its lending projects that include mainstreamed DRR, mostly through efforts to integrate climate resilience into value chains, but there is low focus on the disaster resilience of livestock and fishing communities. The share of all Agriculture and Food GP lending operations with mainstreamed DRR activities rose from 10 to 20 percent between FY10 and FY15 and between FY16 and FY20 in 29 countries—of which 52 percent are IDA countries, 19 percent are Blend countries, and 30 percent are IBRD countries—while the Agriculture and Food GP rarely supports DRR core activities (2 percent during both periods). Eighty-five percent of mainstreamed agricultural projects focused on integrating DRR into crop value chains; very few mainstreamed DRR into livestock and fisheries.

There has been significant progress in mainstreaming DRR in the Transport GP; however, these activities are less frequent in transport operations in Europe and Central Asia and in Sub-Saharan Africa. Although the share of DRR mainstreamed Transport projects rose from 8 to 27 percent, only 6 percent and 10 percent of the Europe and Central Asia and Sub-Saharan Transport portfolios, respectively, included mainstreamed DRR activities. Eighty-six percent of Transport projects with DRR mainstreaming are in middle-income countries, in part because 79 percent of Transport projects approved during the evaluation period were in middle-income countries.

Mainstreamed DRR activities increasingly cover drought risks. Forty percent of projects that mainstream DRR include a focus on drought management in 60 countries. The number of lending operations that mainstream activities to address drought risks has increased from 60 during the first half of the evaluation period to 91 during the second half. Social Protection programs were four times as likely to cover drought risks in the second half of the evaluation period as compared with the first half. The Water GP has increased the number of regional and country-level IWRM projects that strengthen institutional capacity for drought management, such as in the Nile Basin, the Horn of Africa, northeast Brazil, and India (for groundwater management). The Agriculture and Food GP has increasingly focused on drought and pastoral and livestock welfare in Africa.

Mainstreaming of DRR in World Bank operations is associated with staff awareness and relationships, CMU and government champions, and the availability of core disaster risk specialists. Three factors are associated with successful DRR mainstreaming. First, the extent to which staff actively promote and engage on DRR depends on the professional backgrounds and interests of country directors, country managers, task team leaders, program leaders, and practice managers, as well as their relationships with disaster specialists. Core disaster staff turnover acts as a constraint in this respect. Second, DRR support benefits from champions who are capable of coordinating the exercise, both in the government and in the World Bank, as there are often multiple stakeholders with diverging interests involved. Third, successful DRR mainstreaming may require a dedicated core of disaster specialists to contribute their expertise in projects led by other GPs.

Nature-Based Solutions

NBSs can be a cost-effective approach for DRR and can also contribute to climate change mitigation and adaptation goals. NBSs for DRR are approaches that use natural systems to provide DRR and mitigation services, which are a subset of broader NBSs. NBSs for DRR can include the use of bioengineering approaches to increase road resilience, mangrove planting, and the development of riverside parks to protect cities. The general financial case for using NBSs to enhance DRR has been well documented, although it has also been noted that costs and benefits depend on local conditions (World Bank 2019f; WWAP 2018). In combined infrastructure gray-green approaches, green activities can reduce the cost of services by reducing the cost of gray components (by reducing capital and operation and maintenance [O&M] costs).2 Green infrastructure can also generate ancillary social, economic, and environmental benefits related to human health and livelihoods, food and energy security, ecosystem rehabilitation and maintenance, climate adaptation and resilience, and biodiversity (WWAP 2018). For example, according to the Global Commission on Adaptation, the global benefits of protecting mangroves are more than five times the cost

of doing so, as they protect 15 million people from annual flooding (World

Bank 2021c).

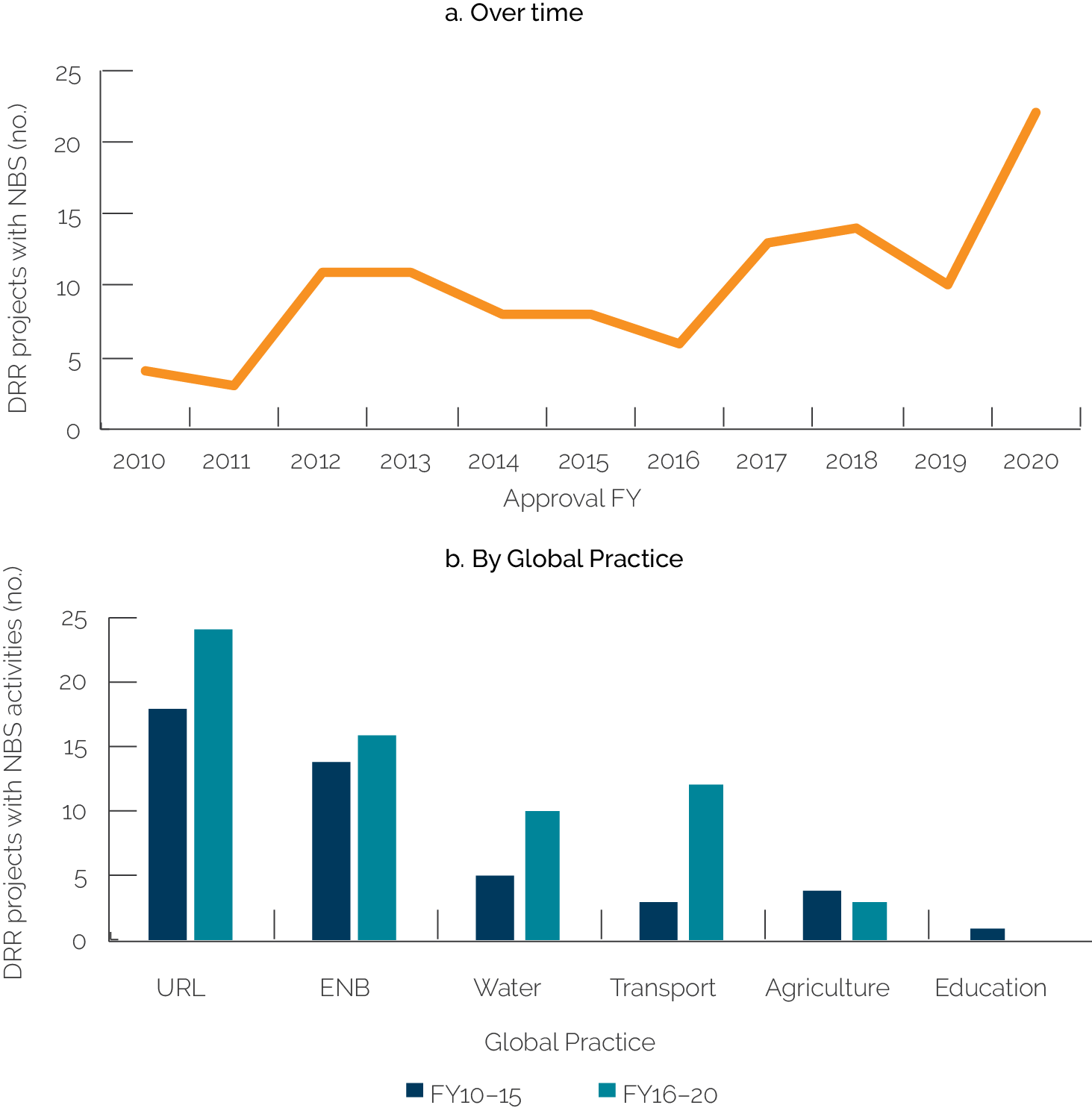

Although it does so infrequently, the World Bank is increasingly using NBSs as part of DRR approaches. Since 2010, the World Bank has supported 110 DRR projects in 48 countries (plus 4 regional programs) that use NBSs, representing 17 percent of the DRR lending portfolio. NBSs have increased since 2010, although from a low base (figure 2.12).

Figure 2.12. Disaster Risk Reduction Lending Projects with Nature-Based Solutions Activities over Time and by Global Practice

Figure 2.12. Disaster Risk Reduction Lending Projects with Nature-Based Solutions Activities over Time and by Global Practice

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: DRR = disaster risk reduction; ENB = Environment, Natural Resources, and Blue Economy; FY = fiscal year; NBS = nature-based solution; URL = Urban, Disaster Risk Management, Resilience, and Land.

However, NBSs for DRR are still concentrated in environmental and urban sector projects. Sixty-five percent of DRR NBS activities were implemented by the Urban, Disaster Risk Management, Resilience, and Land (38 percent) and ENB (27 percent) GPs (figure 2.12). Two-thirds of NBSs–Urban, Disaster Risk Management, Resilience, and Land GP activities are in core DRR projects, often aimed at reducing hydrometeorological risks. The ENB GP uses NBSs for coastal and marine management to mitigate flood risks and as part of land and watershed management to mitigate flood, landslide, erosion, and drought risks. The World Bank has integrated NBSs into 10 percent of all post-disaster operations with DRR elements and 20 percent of predisaster operations. The Water GP is increasingly integrating NBSs, with 10 DRR operations with NBSs approved in the second half of the evaluation versus 5 DRR operations in the first half. These DRR operations include green urban drainage infrastructure, watershed and catchment management, and riverine protection in China, Poland, and Uganda. There is also an increasing number of regional efforts—especially in East Africa—where the Water and ENB GPs collaborate on DRM activities with NBSs at basin or catchment levels. NBSs in transport operations typically include planting vegetation or using other bioengineering measures to stabilize slopes or improve drainage to increase the resilience of critical infrastructure to floods and landslides.

The use of NBSs in DRR operations is constrained by an insufficient level of evidence on NBSs’ benefits, as well as clients’ and staff’s lack of familiarity with these approaches and their perception that the approaches are too complex. Although the use of NBSs is increasing, little is known about their effectiveness in the portfolio. Such analysis requires rigorous considerations of costs and benefits, including social and environmental (such as ecosystem services and climate change) benefits. An analysis also requires scientific understanding of how NBSs function to reduce disaster risk. As noted by the Global Program on Nature-Based Solutions for Climate Resilience, “just planting a tree or protecting a forest, however, is not necessarily NBS” (Zanten et al. 2021). Although mangrove planting is a popular restoration approach, many planting projects fail to restore a functioning mangrove system, often due to inadequate understanding of socioeconomic conditions, ecological conditions, or a lack of community support. As such, it is critical to ensure that NBSs are, in fact, solutions (Zanten et al. 2021). Staff who are less exposed to programs such as the Global Program on Nature-Based Solutions for Climate Resilience, which is situated within the same GP as the GFDRR and the City Resilience Program, may be less familiar with NBSs and less able to benefit from the technical support offered by those programs. Recently, African regional directors requested greater GP collaboration on NBSs. However, adoption of NBSs is also challenged by perceptions that they are too complex because they require many staff specializations and time-consuming engagement with land users. World Bank staff cited the short timeline of World Bank projects as a limitation and the need for greater skills integration.

- The evaluation team considered countries that (i) had at least one World Bank lending project between fiscal year 2010 and fiscal year 2020 and (ii) have an assigned lending status (International Development Association/International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/Blend) in 2022.

- For example, the use of mangrove restoration along the coasts of Vietnam to enhance existing gray infrastructure and reduce flood risk significantly cut the cost of damages to the dikes and resulted in large amounts of savings associated with avoided damages to private property and other public infrastructure (IFRC 2011).