The World Bank Group Outcome Orientation at the Country Level

Chapter 2 | Aiming for Outcomes

Highlights

The model of how the World Bank Group aims for outcomes at the country level is sound and, for the most part, country teams practice this model well.

The Bank Group’s country strategies set out to influence country outcomes and frame their objectives in terms of outcomes, while facing difficulties in being selective because of internal competition for program space and heterogeneous client demand.

The Bank Group pursues its objectives through both direct and indirect pathways, but indirect pathways are not well articulated in country documents and the relatively short country engagement cycle does not promote the long-term vision needed to sustain indirect pathways.

There has been progress in integrating teams from the International Finance Corporation (IFC) and the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency into Country Partnership Framework design, but Country Partnership Frameworks do not serve IFC’s strategic needs well. This motivated IFC to launch its own internal country strategies and other country products. Early experience with these IFC country strategies shows that they offer potential for increasing IFC’s focus on country outcomes; close alignment with the World Bank and Bank Group country engagement is a condition of success and of avoiding risks of duplicated efforts.

This chapter reviews how country teams aim for outcomes in their country engagement. The country engagement is not meant to be the simple aggregation of the Bank Group’s discrete projects taking place in a country. Its value proposition is in providing a strategic platform for articulating and coherently managing the Bank Group’s response to country needs. It is intended to pursue meaningful and significant objectives, to combine instruments in the pursuit of short- and long-term development trajectories, and to combine the strengths of the three Bank Group institutions.

Objectives for Country Engagements

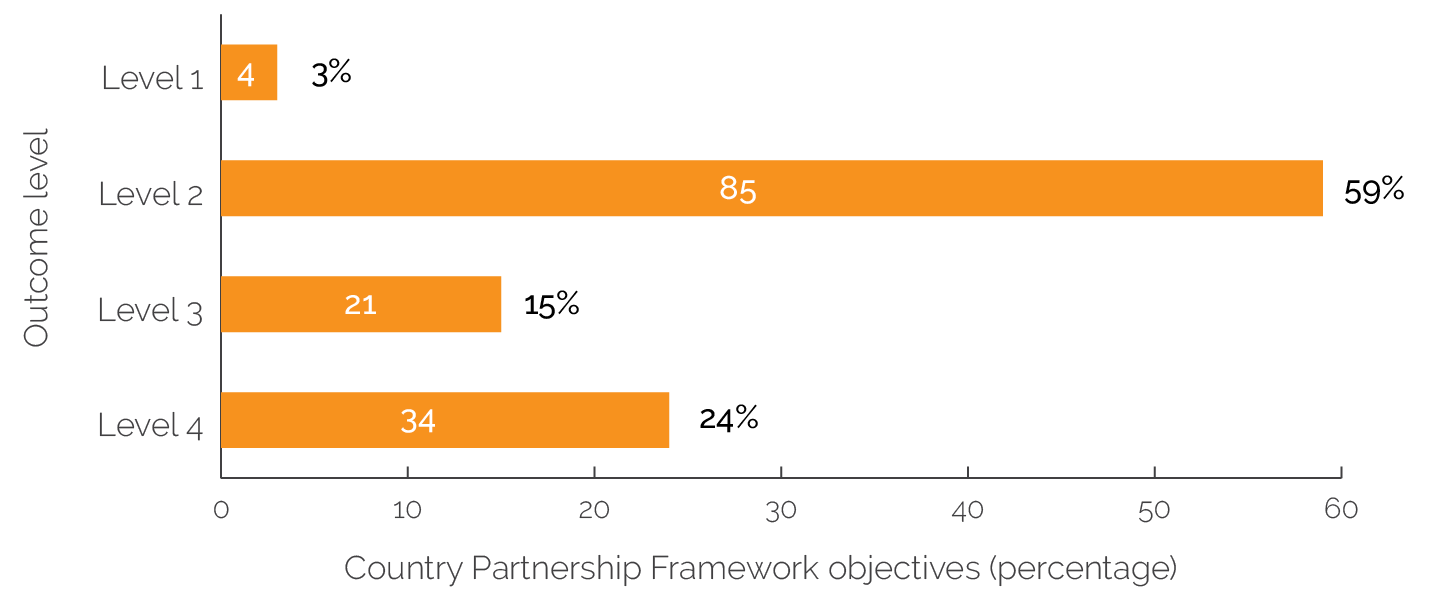

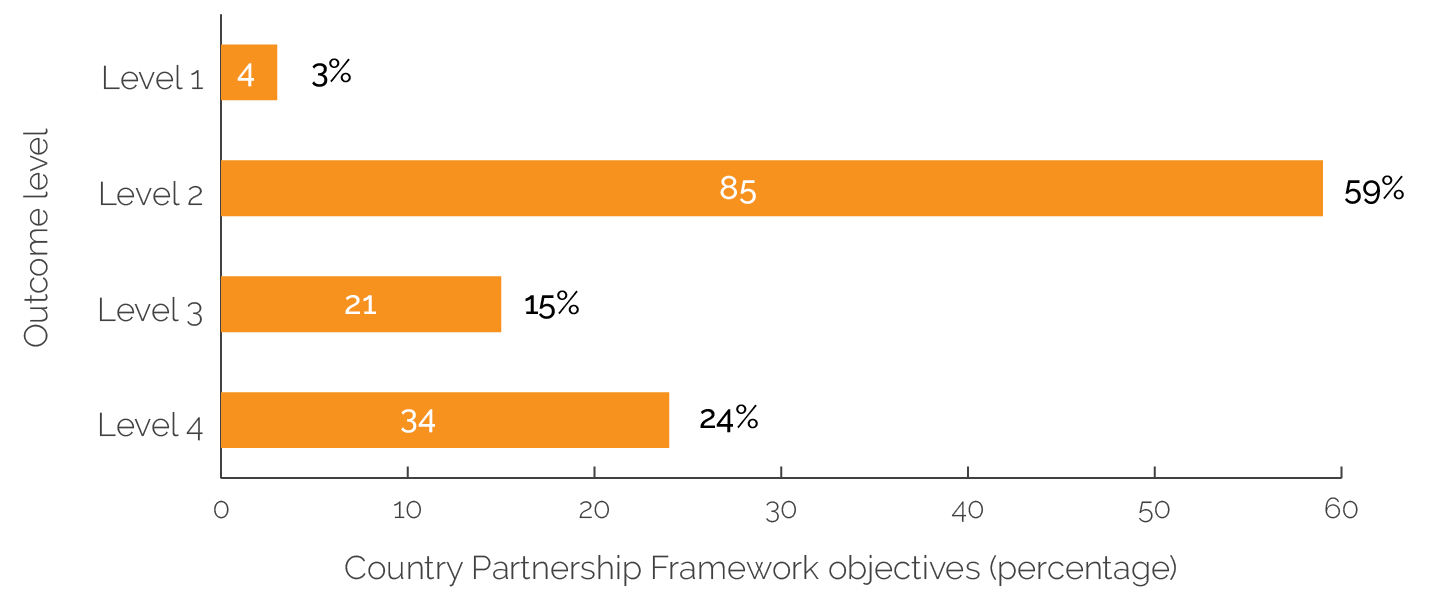

The Bank Group’s country strategies set out to influence country outcomes and frame their objectives in terms of outcomes. The CPF is the institutional platform created to identify the strategic direction of the Bank Group in each country. Country teams use this platform well to articulate how the Bank Group will contribute to the longer-term development trajectory. Aided by the SCD and in-depth consultation, the CPF narratives spell out the country’s most critical development challenges and how Bank Group interventions will contribute to address them in explicitly identified outcome areas and sectors, each with its own objectives. The evaluation applied a classification plan developed for the RAP 2020 to identify the range of objectives pursued in CPF and indicators used to capture them (box 2.1). In the CPF and outcome areas reviewed for this evaluation, nearly all objectives were framed in terms of outcomes. A quarter sought to influence long-term country outcomes, seeking a major change in service delivery or governance systems or a sustained benefit to citizens (level 4); 15 percent sought to change the behavior or capability of key government agents or ultimate beneficiaries (level 3); and while the majority pursued intermediate outcomes (level 2)—whereas virtually none were defined in terms of outputs (level 1). There is significant variation across outcome areas, however, with strategies more likely to frame intangible goals such as governance in terms of high-level outcomes (figure 2.1). Interviews also made clear that country teams understand well the country outcomes they are working toward.

Box 2.1. Objective and Indicator Classification

Level 1—Output. Product or service provided within the control of the client.

- For example, creating a national performance management framework (Botswana CPF FY16–20).

Level 2—Immediate outcome. Development of the capability of a group or organization, an initial benefit to people, infrastructure delivered.

- For example, improving access to quality education and health services in targeted rural areas (Indonesia CPF FY16–20).

Level 3—Intermediate outcome. Stakeholders apply a new capability to solve an issue; change in the lives of ultimate beneficiaries.

- For example, enhanced educational outcomes for better employability (Bulgaria CPF FY17–22)

Level 4—Long-term outcome. A sustained change in delivery or governance or a sustained benefit to an ultimate beneficiary.

- For example, improving living standards in the lagging areas (Sri Lanka CPF FY17–20).

Source: World Bank 2015b, 2015f, 2016b, 2016e, 2020b.

Note: CPF = Country Partnership Framework.

In selecting objectives for country engagements, the most commonly observed challenge is the difficulty of being selective because of internal competition for program space. Among the 29 CPFs reviewed for this evaluation, CPFs with more objectives were less likely to have good-quality indicators that adequately measured the objective. In interviews, staff argued that the Bank Group “spreads itself too thin in CPFs,” which reduces the chances of significantly influencing country outcomes. Interviewees believe the lack of selectivity is driven by the World Bank operational model whereby Global Practices jockey for space in CPF envelopes, in part for the associated work programs and budget but in part because of the institutional incentives for them to maximize lending portfolios. As one staff member put it, “I know there is no space in the portfolio for my sector, but my practice manager still pushes me to try to get a project in.”

Figure 2.1. Country Partnership Framework Objectives by Outcome Level

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: n = 144 Country Partnership Framework objectives. Level 1: Outputs; level 2: Immediate outcome; level 3: Intermediate outcome; level 4: Long-term outcome.

Challenges in selectivity are also driven by heterogeneous client demand. Client demand is a key factor in country program design. As a financial institution, the Bank Group needs to balance strategic and opportunistic responses to development challenges to generate the lending on which its business model relies. This is particularly true of IFC and MIGA investments and guarantees. In certain contexts, the heterogeneity of client demand significantly constrains country teams’ ability to aim for a selective and sustained contribution to country outcomes. Especially in countries where Bank Group financing volumes are small compared with overall investment, it can be unrealistic to expect to achieve significant effects on country outcomes. In countries where the Bank Group faces significant competition for lending, the imperative to lend can make it difficult to be selective, so CPF objectives are deliberately written to be very broad to ensure that any demand that arises can be classified as relevant to the strategy. Both effects are prevalent in large upper-middle-income countries, which tend to articulate broad high-level objectives. Similarly, in countries with very fast-changing government priorities, such as Peru or Sri Lanka, of necessity, the CPF is written in broad terms to give country teams room to maneuver during the cycle with fast turnaround.

Country leaders use a range of practices to curb competition and enhance selectivity to achieve country objectives. Country managers and directors play a pivotal role in catalyzing the Global Practice (GP) energy and maintaining the focus of the portfolio. Some are more effective than others. Interviewees consistently see leadership skills as the most critical factor, but some tools and filters have also proven useful. For example, drawing lessons from the CLR, the Zambia CPF used spatial alignment to tighten the selectivity of the use of IDA funds. It identified three spatial circles as the poorest areas of the country and put in place mechanisms to prioritize investments in these high-need areas. For the preparation of the Morocco CPF, the country leadership organized multi-GP results teams around focused outcomes. This took away the competition for securing a place in the CPF for a particular GP. The Morocco CPF was also designed as an adaptive framework in contrast with more conventional practices, as shown in table 2.1. A CMU staff member described it as “a living strategy that incorporates learning-by-doing and constantly adapts to country circumstances and unforeseen or changing priorities.”

Table 2.1. Morocco’s Adaptive Country Partnership Framework in Contrast with More Conventional Approaches

|

From |

To |

|

CPF as a document |

CPF as a living strategy that needs adjustments |

|

Overly ambitious project design that does not get implemented |

Experimental design that learns early and incorporates lessons as it scales |

|

Linear log-frames and causal chains |

Recognition that the World Bank Group works on complex problems in complex systems |

|

Measuring what is known |

Measuring what is important |

|

Supply-driven, sector-focused interventions |

Multisectoral programmatic approaches |

|

Focusing on project design |

Focusing on implementation and implementation support |

|

Reputational risk as a key driver for decisions |

Learning mind-set to achieve results and generate capacity by doing |

Source: World Bank 2019m, 37.

Note: CPF = Country Partnership Framework.

In Romania, the country manager uses CPF filters to provide a strong strategic direction to sector teams developing new business in the country. All new operations and reimbursable advisory services (RAS) have to demonstrate how they contribute to institutional strengthening, which is the Bank Group’s main contribution to Romania’s development. In the Western Balkans, the country director is requiring that all proposed advisory services and analytics (ASA) clearly articulate how they contribute to a specific outcome area of the CPF and that they include an outcome indicator. In the Pacific Islands, the CMU has established a ceiling on the number of projects that can be prepared for a country within an IDA cycle to avoid overwhelming thin capacity. This has helped delimit the sectors where the World Bank is active.

Pathways to Achieving Development Objectives

The Bank Group pursues its objectives through direct and indirect pathways to influence clients’ development trajectories. Bank Group country engagements have direct effects from investing in assets, services, or other measures that yield short-term benefits to citizens that are tangible, measurable, and attributable to specific interventions, and indirect effects that strengthen institutions, improve the quality of governments’ spending, or catalyze private sector development. These indirect effects also come from fostering learning-by-doing in governments and market institutions and can originate from both project and nonproject instruments. By engaging with Bank Group interventions, clients gain capacity in project management, procurement, financial management, safeguards, and so on, ultimately improving how governments function. They are among the most common CPF objectives. About one-third of CPF objectives coded for this evaluation explicitly aimed at building institutional capacity within a sector. Country teams working in International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD) countries consider that this is the most significant contribution to country outcomes, because direct investment in service delivery can only have marginal effects. For example, in European Union (EU) member or candidate countries, the World Bank is a small funder compared with the EU but is playing a key role in addressing the institutional weaknesses (institutional bottlenecks and weak capacity in managing funds, implementing projects, and carrying out policy changes) that prevent the countries from taking full advantage of the financial support provided by the European Commission. The Bank Group’s main contributions in Romania and the Western Balkans are focused on addressing these challenges, mainly through RAS for the former and a mix of technical assistance and lending in the latter.

However, indirect pathways to country outcomes are not well articulated in country documents. In part, this is because theories of change for indirect pathways are not as well articulated compared with those of direct pathways. Although indirect pathways are one of the most important contributions of the Bank Group to country outcomes, there are still many unknowns on how institution building connects to country outcomes, including identifying the type of support that leads to better institutions and understanding under what conditions stronger institutions lead to better outcomes for citizens (World Bank 2019f). The results measurement system is also not designed to encourage teams to emphasize indirect pathway effects. The effects of these pathways for citizens do not materialize immediately, causal chains are long, and the influence of specific actors is harder to trace and the effects harder to quantify. For example, in the Solomon Islands, Bank Group projects on rural development and youth employment have probably played a contributing role in peace and stability through project activities that build social dispute resolution mechanisms, increasing rural incomes, improving service delivery, and providing jobs in some areas. The country team was dissuaded from emphasizing those types of changes in their country evaluation products, because they are hard to quantify and to attribute to specific interventions.

The relatively short CPF timeline does not match the long-term vision needed to sustain indirect pathways. Interviews with country teams show that though indirect pathways and long-term development trajectories are part of their thinking, the platforms created by the country products do not promote a long-term vision. There is limited discussion in CPFs or other country documents about how each cycle builds on past achievements and contributes to long-term development trajectories. Although CPFs use the active portfolio as a baseline and the closing portfolio as the end line to assess results, there is no line of sight on the long-term development trajectory. In our sample of CPFs, there were only four country engagements reviewed that provided a sense of how the Bank Group will seek to maintain and strengthen outcomes over multiple country engagement cycles (Afghanistan, Romania, North Macedonia, and Vietnam).

Aiming for Development Objectives across the Bank Group Institutions

The CPF is intended to provide an overarching strategy incorporating not only the World Bank but also IFC and MIGA. The Bank Group tries to pursue objectives through mixing and sequencing multiple interventions to achieve outcomes greater than the sum of their parts; however, this is not always possible. At the CPF stage, country teams articulate well how the combination of Bank Group operations aims to influence certain outcomes. When such packages exist, the intervention logic laid out in the CPF narrative and in the dedicated portion of results matrixes explains quite well how multiple interventions, including ASA, private sector investment, and guarantees, contribute to each objective. However, where portfolios of activities within sectors are small, articulating a results chain that conveys cumulative effects across operations and contributions to higher-level objectives can be artificial. For instance, in the Western Balkans or the Pacific Islands, portfolios tend to have a single project in any given sector that can be the sole vehicle for influencing outcomes. In these contexts, project objectives and country objectives are largely the same, and so the country-level results system adds little value to the project-level results system.

There has been progress in integrating IFC and MIGA teams into the CPF design, but CPFs do not serve IFC’s strategic needs well. According to interviews with IFC, MIGA, and World Bank staff, the inclusion of IFC and MIGA teams in the preparation of the SCD and CPF has improved over time. In the sample of CPF objectives reviewed for this evaluation, IFC and MIGA were integrated into 40 percent of the CPF objectives, with 39 percent as contributors to Bank Group–wide objectives, and 1 percent as a stand-alone IFC/MIGA objective. MIGA’s risk management officers need to have an in-depth understanding of the country to arrive at a risk rating, which is at the core of MIGA’s business model. Thus, MIGA values highly the knowledge sharing and network building across the Bank Group that comes with the country engagement model. MIGA participates in the CPF process in all the countries for which the Bank Group is engaged but prioritizes its involvement in countries that are of strategic priority, primarily IDA and fragility, conflict, and violence (FCV) countries. Conversely, more than two-thirds of IFC staff interviewed continue to consider the CPF as a World Bank-centric document geared toward an external audience and with limited influence on IFC’s strategic outlook. The content is considered too upstream and detached from IFC’s business model, which engages with specific corporate clients rather than governments. It is not used by IFC as a road map for action within countries. Staff consider it inherently difficult for the CPF to represent IFC well and to serve its strategic needs; the strategy discussions and document concentrate on the larger World Bank engagement, and the consultations prioritize the single government client rather than numerous private sector clients.

IFC launched its own Country Strategies (CSs) in 2016 to improve IFC’s inputs to the CPF and to better guide its investment decisions within countries. IFC has introduced a number of internal country products with the intention of informing the Bank Group country cycle: the joint IFC-World Bank Country Private Sector Diagnostics to inform and complement the SCD, the IFC CSs to lay out strategic priorities and reinforce IFC’s position in the CPF, and a country-level business plan and its subsequent reviews. The CS articulates clear investment and sometimes development impact scenarios captured by “if-then” matrixes, which lay out critical policy barriers where reform (and potentially World Bank engagement) could unlock investment opportunities. The process of developing CSs has created a useful platform to bridge the gap between country and industry teams. In interviews, staff report largely positive feedback on the consultations, team brainstorming, and leadership involvement in the preparation of the CS. Anchoring advisory and investment decisions in a country framework marks a departure from business as usual at IFC. Acceptance by industry teams of this country lens is driven by the IFC 3.0 strategy, the commitment of the senior management team (regions and industries), and the ability of the CS to add value to business development activities.

Early experience with IFC CSs suggests they offer potential for increasing IFC’s focus on country outcomes. The process of combining an assessment of country development gaps and IFC’s comparative advantage with market data and analytics and a detailed understanding of regulatory and capacity barriers enables IFC to develop a common road map of priority sectors for engagement. This has the potential to enhance the internal coherence of IFC interventions and depth of impact by influencing which sectors IFC is active in. When there is strong support from both regional and industry directors, CSs can influence project decisions by guiding business development efforts and discouraging project proposals that are not well aligned with CS priorities. Links to investment scenarios and expected developmental impact are made more explicit in if-then matrixes. IFC CSs contain investment scenarios that are articulated based on the likelihood of specific reforms taking place. In scenarios where few reforms take place, the matrix identifies the IFC 1.0 and 2.0 investments that could take place by industry. The matrix also identifies IFC 3.0 projects that could materialize in high-reform cases. These matrixes make explicit specific IFC requests from the World Bank or the government to work on reform processes that could unlock IFC investments. All if-then matrixes articulate an estimated IFC investment target for each scenario. However, only a few lay out a developmental impact objective linked to the scenarios. This practice is a good marker of enhanced country outcome orientation and should be encouraged but need not include quantified targets that could create false expectations of precision.

Close alignment with the World Bank and Bank Group country engagement is a condition of success. IFC’s country products are supposed to feed into the Bank Group country engagement cycle. The first set of IFC Country Private Sector Diagnostics and CSs were not always timed to be integrated in the SCD and CPF, and so the CPFs did not capture their contents, leading the two to function as parallel and duplicative systems. However, sequencing of IFC and Bank Group country products has been improving over time. Moreover, the investment scenarios and necessary reforms are not always discussed with the government counterparts, which means that some of the assumptions on which IFC’s CSs rest can become “wishful thinking,” as one interviewee put it. The degree of alignment and joint commitment between the Bank Group and IFC on the if-then matrix is highly dependent on the relationships between World Bank country director and IFC regional leadership. It was clear from interviews with IFC staff and management that the proliferation of strategy-related documents puts a strain on IFC staff. Interviewees highlighted that close coordination with World Bank colleagues is necessary to avoid duplicative efforts and ensure alignment between IFC and Bank Group country products, but this comes with transaction costs.