The World Bank Group in Ecuador

Chapter 4 | Complementary Support for Improved Social Protection Systems

Highlights

The World Bank’s support for the economic transition was complemented by continuous technical assistance on social protection. This technical assistance built a foundation for providing expanded support to poor and vulnerable people throughout the major reforms.

Evolving from an initial narrow focus to improve nutrition programming, the World Bank’s social protection agenda expanded steadily from 2008 to a much broader scope of diagnostics, which aimed to promote solutions to shortfalls in Ecuador’s social service delivery and data collection systems.

After the change in administration, implementation of this agenda was spearheaded by the Social Safety Net Project and underpinned by regulatory reforms supported by the Inclusive and Sustainable Growth and the Green and Resilient Recovery development policy operation series. Focus areas included strengthening the Social Registry and nutrition programming to mitigate the impacts of subsidy reform, COVID-19, and climate change.

The World Bank’s work in social protection across the evaluation period demonstrated effectiveness with respect to relationship building and in terms of measurable improvements in targeting and service delivery.

These achievements notwithstanding, the World Bank was largely unsuccessful in improving low institutional capacity in a principle implementing ministry, reducing effectiveness of the Social Safety Net Project’s sustainability component.

Chapter Objectives and Methodology

This chapter evaluates the World Bank’s efforts to improve Ecuador’s social protection services. NLTA, ASA, and lending are reviewed, with contributions assessed in terms of (i) relevance to the recognized development priorities of maintenance and expansion of social protection and inclusion, in the context of the evolving relationship (recognizing that certain types of support became feasible only as engagement was restored), and (ii) the effectiveness of support (examining whether interventions achieved their stated objectives in the area of maintaining and expanding achievements in social protection and inclusion). With respect to effectiveness, the chapter considers both measurable results and process-oriented outcomes (for example, influence dividends) concerning government uptake of technical guidance and policy advice. Although the latter cannot be weighted equivalent to quantified outcomes, they do reflect steps along a given results chain leading to the desired consequence.

The scope of analysis is limited to noncontributory schemes, as opposed to the entire social protection matrix. Although Ecuador has contributory social insurance programs that cover formal labor market workers via mandatory saving mechanisms,1 most low-income beneficiaries (who are either informal workers or unemployed) have historically been covered exclusively by the social safety net (box 4.1), which consists of conditional and unconditional cash transfer programs and complementary social services, implemented by the Ministry of Economic and Social Inclusion (MIES).

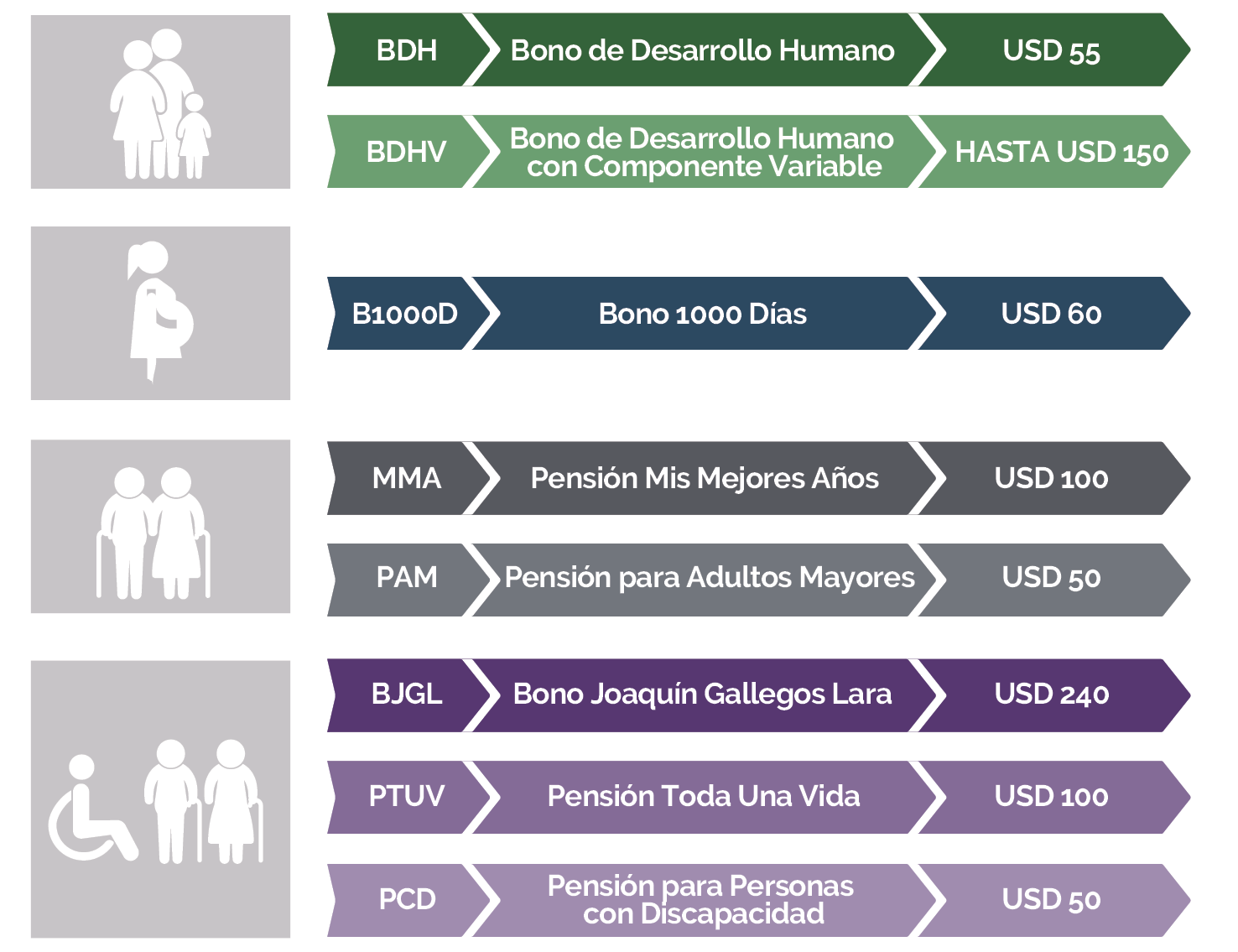

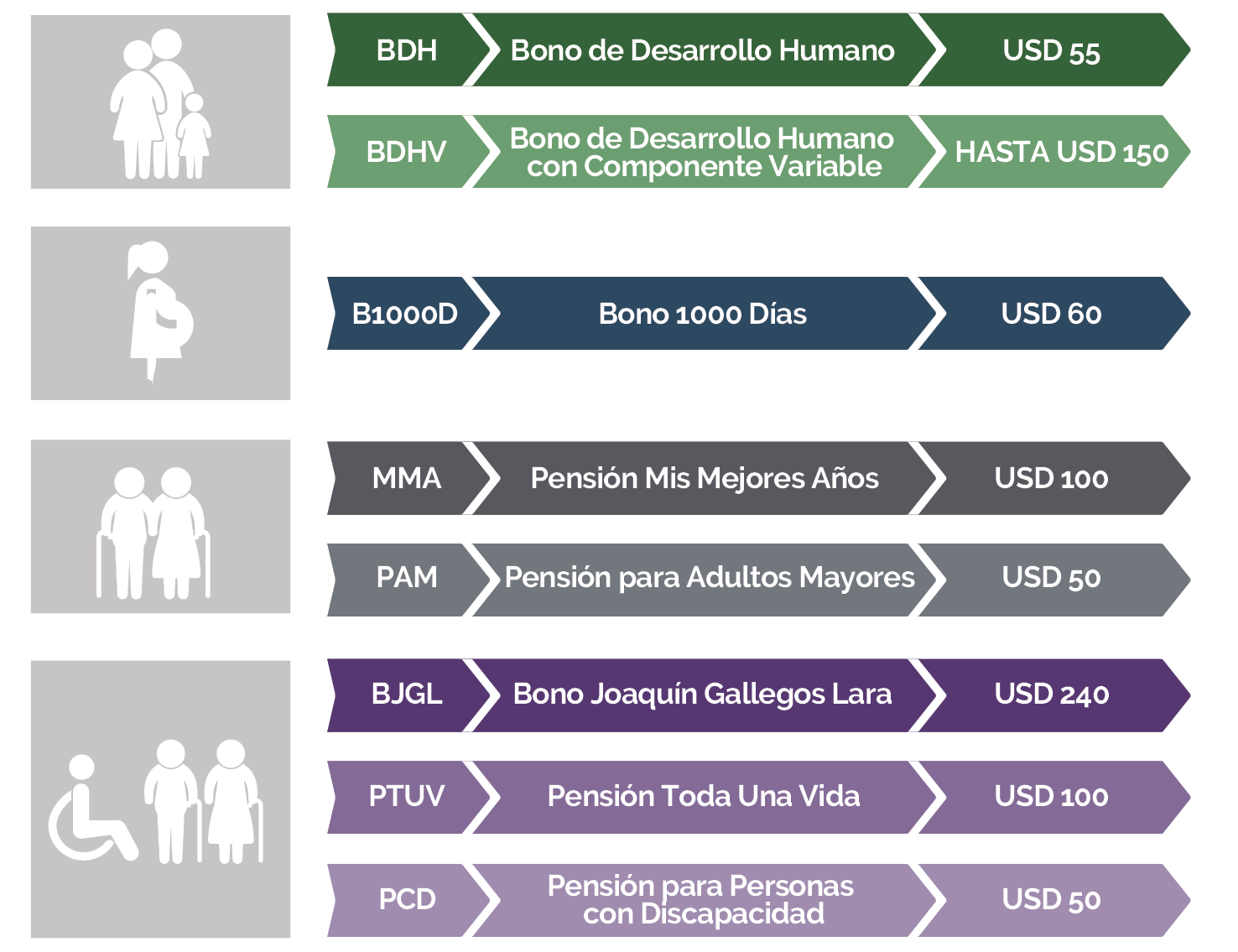

Box 4.1. Major Components of Ecuador’s Social Safety Net System

Bono de Desarrollo Humano (BDH) provides monthly income support with health and education conditionalities, targeted to poor and extremely poor households with children under 18 years of age.

BDH con Componente Variable targets extremely poor families with children under 17 years of age, providing a monthly fixed transfer and an additional transfer based on the number of children.

Bono 1000 Días, launched in 2022, provides monthly income support with health and nutrition conditionalities, targeted to poor and extremely poor pregnant women and children under 2 years of age.

Crédito de Desarrollo Humano: Whereas BDH is a monthly transfer meant to guarantee a minimum level of consumption, Crédito de Desarrollo Humano pays a yearly amount aimed at promoting productive investments and can be requested only by households that are active recipients of BDH. It is informally considered the “graduation program” of BDH.

Pensión Adulto Mayor and Pensión para Adultos Mayores en Extrema Pobreza—Mis Mejores Años provide monthly unconditioned income support to poor and extremely poor seniors over 65 years of age.

Pensión para Personas con Discapacidad, Pensión Toda Una Vida, and Bono Joaquín Gallegos Lara provide monthly unconditioned income support to poor and extremely poor people with disabilities (figure B4.1.1).

Figure B4.1.1. Major Components of Ecuador’s Social Safety Net System

Note: All transfer amounts circa February 2023. USD = US dollar.

Source: Ministry of Economic and Social Inclusion.

Description of World Bank Support

The government’s social safety net policy at the start of the evaluation period did not adequately protect poor and vulnerable people. Despite the administration’s heavy investment in public services, errors of inclusion, exclusion, and duplication in targeting for the flagship BDH and related transfers were widespread. The challenge was exacerbated by low transparency regarding verification of recipient eligibility data and weak compliance with the program’s health and education conditionalities (Mideros and Gassmann 2017),2 both of particular concern given persistently high rates of malnutrition and other risk factors among vulnerable groups.

These shortfalls were traceable in large part to a service delivery system that was poorly aligned with transfers and a data collection strategy that lacked cohesion and accountability. With respect to service delivery, implementation was compromised by (i) poor internal coordination within MIES, (ii) poor coordination between MIES and other government institutions providing complementary services, (iii) weak monitoring of local service providers, and (iv) infrequent or nonextant evaluation of the impact of individual social assistance programs.3 As a result, many beneficiary families who were intended to receive cash transfers in conjunction with an integrated package of services (thus facilitating compliance with BDH conditionalities) frequently received either only the transfer or an incomplete, irregularly accessed package of services. In addition, the Crédito de Desarrollo Humano informally considered the “graduation” strategy for beneficiaries of BDH (see box 4.1) and faced design and operational challenges preventing it from ensuring a sustainable exit strategy for program users. With respect to data collection, the beneficiary selection process faced challenges related to outdated information and targeting accuracy. Although the Social Registry Unit (Unidad del Registro Social; URS) was created in 2009 to address these issues, it initially had neither the legal capacity to fulfill its mandate nor enough budget and human resources to perform its designated role as the unique entry point for accessing social programs.

Between 2007 and 2019, the World Bank generated over 20 diagnostic knowledge products to address these challenges. Predicated on a single ASA in 2007 to strengthen implementation of nutrition programming (World Bank 2007), World Bank support to MCDS and MIES expanded steadily from 2008, eventually including a wide portfolio of NLTA ranging from (among other things) studies to inform family planning and early childhood development (ECD) services, to research on vocational training and labor market inclusion to inform an exit strategy for BDH via the Crédito de Desarrollo Humano, to diagnostics for strengthening capacity of rural households and community authorities to monitor and improve children’s physical growth and developmental outcomes. From 2009, the World Bank also provided technical assistance to the National Institute of Statistics and Census on the Human Opportunity Index and Poverty Assessment series. These ASA, including the Survey on Household Socioeconomic Status, collected a wealth of information on poverty mobility and data on BDH recipients, facilitating MCDS’s assessment of multiple aspects of BDH’s targeting criteria and strengthening the case for improving the government of Ecuador’s data harmonization protocol. In line with the World Bank’s work with the National Institute of Statistics and Census, a comprehensive census sweep (RS2018) was initiated in 2018 to improve the accuracy of the Social Registry database.

After the change in administration, the World Bank provided policy support and direct operational assistance to implementing agencies. From 2019 onward, the World Bank resumed lending support through (i) the Social Safety Net Project, which provided direct support on targeting and service delivery, and (ii) two DPO series (Inclusive and Sustainable Growth and Green and Resilient Recovery). Both DPOs included pillars to foster inclusion and stipulated regulatory reforms that underpinned the implementation goals of the Social Safety Net Project as follows:

- Mandating that public executive agencies share their data registers with the URS.4

- Mandating the permanent updating of Social Registry data every three years.5

- Expanding the Social Registry’s objectives to extend beyond targeting the extreme poor.6

- Creating a unit within the Ministry of Economy and Finance to support the design of compensation mechanisms to mitigate the impact of subsidy reforms.7

World Bank operations prioritized reducing malnutrition and protecting the vulnerable from climate-related disasters. Both the Social Safety Net Project and the Green and Resilient Recovery DPO series supported the establishment in 2021 of the National Strategy “Ecuador Grows without Child Malnutrition.” This included the introduction of a nutrition assistance package for pregnant women and children consisting of a cash transfer (Bono 1000 Días)8 linked to ECD services provided by MIES and the Ministry of Public Health, improved provision of water and sanitation services, and an annual statistical survey of chronic child malnutrition rates to monitor progress and better target the prioritized package. In addition, the Green and Resilient Recovery DPO series supported the creation of the Single Registry of Victims (Registro Único de Afectados y Damnificados; RUAD) database, linked to the URS and designed to improve MIES’s capacity to identify beneficiaries at high risk of natural disasters. This database supported activities under the Social Safety Net Project, which added the Contingency Emergency Response Component in 2023 (World Bank 2023b), after increased risk of severe weather events.

During COVID-19, the World Bank supported the government’s emergency efforts to reach vulnerable households not covered by social assistance programs. Both DPOs and the Social Safety Net Project pivoted during COVID-19 to support the following actions:

- Creation of an emergency cash transfer program—Bono de Protección Familiar—explicitly designed to reach highly vulnerable households not covered by existing social assistance programs. These new beneficiaries were identified using initial results from RS2018 and were eligible only if designated as “nonwage earners” or “informally employed.”

- Facilitating access to this transfer by expanding the availability of retail banking agents, adjusting the calendar of payments, and improving communication with beneficiaries, including promotion of digital banking via remote uptake of basic accounts using mobile phones.

- Creating the Migratory Registry to be shared with the URS and based on information drawn from the Migratory Census to ensure provision of public services to Venezuelan refugees during the pandemic.

Relevance of World Bank Support

Extensive early diagnostics identified weaknesses in Ecuador’s social safety net system and generated evidence to inform improvements. The ASA released by the World Bank in 2007 provided a detailed evaluation of the country’s inefficiencies in tackling chronic undernutrition (World Bank 2007). The report recommended a revised approach to increase agency accountability via improved data collection and strengthened delivery of proven, cost-effective interventions in regions where stunted growth of children was highest, primarily via ECD services provided by MIES. These recommendations drew on Ecuador-specific data (for example, with respect to drivers of undernutrition among Indigenous children) and regional and global evidence (Black et al. 2008; Horton et al. 2010) and provided a springboard for the aforementioned spectrum of NLTA on social assistance services, which, although opportunistic, was underpinned by a farsighted World Bank strategy to improve the effectiveness of public spending on the entire social safety net system. This strategy drew on a solid evidence base of global learning and the Ecuador-specific studies (World Bank 2012b).

Operational support conducted after 2018 was grounded in the substantial analytic work previously performed. In line with the World Bank’s work on private sector development, diagnostics for social protection conducted before 2018 informed the ISN, the CEN, both DPO series, the Social Safety Net Project, and the SCD, providing a robust foundation for government collaboration and the overall design of operations. Additional diagnostics, which underpinned the relevance of post-2018 social protection operations, included the Rapid Social Response Program to assess the contribution of Ecuador’s social protection system in reducing stunted growth of children and the poverty and social impact assessment showing that addressing inclusion and exclusion errors in BDH could reduce extreme poverty by 2–3 percentage points among women-headed households.

Policy reforms to improve the URS were relevant to various country needs. Improving the URS’s capacity to accurately identify low-income households was fundamental to strengthening the social safety net. As such, both DPO series stipulated regulatory reforms to improve that agency’s reach and functionality. These reforms were also critical for the introduction of the emergency transfer program during COVID-19. With respect to climate change, the creation of RUAD, including a mandated link to the URS, was intended to facilitate MIES’s capacity to identify and assist beneficiaries at high risk of natural disasters.

Strengthening the capacity of the URS database to identify vulnerable households was also relevant to reducing malnutrition. In 2021, the Social Registry covered 3.1 million households, of which only 30 percent had documented access to social assistance programs. Child malnutrition stood at 23 percent, one of the highest rates in the region and indicative of the pressing need for the nutrition assistance package described in this chapter. Improving the capacity of the URS to target the most vulnerable households increased the likelihood of these nutrition services reaching children that needed them most. In addition, because many of these households were also the most vulnerable to climate change and other shocks, this objective dovetailed with the relevance of RUAD. It is for precisely this reason that the Contingency Emergency Response Component was added to the Social Safety Net Project in 2023.

Effectiveness of World Bank Support

The extensive portfolio of diagnostics and NLTA generated between 2007 and 2018 is linked to measurable improvements in targeting and service delivery. Between 2007 and 2019, in anticipation of resuming operations, the World Bank built credibility with the government of Ecuador counterparts regarding recommendations to strengthen both the URS and nutrition and related social services. These recommendations were then operationalized under the Social Safety Net Project and the Inclusive and Sustainable Growth DPO series and can be linked to documented improvements (discussed in this section). In addition, they can be linked to process-oriented outcomes whose trajectories spanned the entire evaluation period, strengthening the World Bank’s dialogue and influence in the sector as follows:

- The World Bank’s knowledge work influenced how MIES and the Ministry of Public Health approached nutrition surveillance and ECD counseling. From 2007, World Bank ASA promoted (i) educating parents regarding the importance of growth monitoring and antenatal care and (ii) routine monitoring of height for age both to improve data harmonization between MIES and the Ministry of Public Health and to enable provincial civil registries to track individuals from birth (World Bank 2007).9 Both of these strategies were implemented under the Japan Social Development Fund: Growing with Our GUAGUAS (Children) project beginning in 2012. Results from this pilot included substantially reduced chronic malnutrition in historically high prevalence parishes of Chimborazo.10 The nutrition assistance package, initiated by Secretaría Técnica de Ecuador Crece Sin Desnutrición Infantil in 2022 with support from the World Bank, has adopted the approach nationwide.

- The World Bank’s knowledge work also influenced how the National Secretariat for Planning and Development, MCDS, and other government actors approached data collection. From 2009, the World Bank used results from the Human Opportunity Index and the Survey on Household Socioeconomic Status surveys and other ASA to highlight the targeting and coverage shortfalls of BDH and related transfers and to advocate for a more cohesive and transparent data collection system, including an independent URS empowered to request and analyze data from public executive agencies. Similarly, this and related objectives were implemented as prior actions under two DPO series during the Moreno administration.

The World Bank’s support of the URS after 2019 can be linked to documented improvements in BDH targeting. Between 2019 and 2023, there were several measurable improvements in the targeting accuracy of BDH and related cash transfers.11 This progress can be largely attributed to strengthened URS performance, which can, in turn, be partially attributed to World Bank support. Given the absence of major reforms that could have led to similar outcomes, it is reasonable to infer that the World Bank’s work on strengthening the URS before 2018 can be linked to improving the targeting of Ecuador’s social protection system thereafter—namely, in terms of extending coverage of poor and vulnerable households. These improvements to BDH targeting include the following:

- The share of poor households included in the Social Registry increased from 38 percent in 2019 to 91 percent by 2021 via increased data collection and methodological index improvement (World Bank 2024a).

- The share of extremely poor households with updated information in the Social Registry increased from 12 percent in 2019 to 96 percent in 2023.

- The share of poor households receiving BDH and BDH con Componente Variable increased from 38 percent in 2020 to 71 percent by 2023.

- By 2023, the share of extremely poor older adult beneficiaries of Pensión para Adultos Mayores en Extrema Pobreza—Mis Mejores Años had increased from 9 percent to 53 percent.

World Bank support can also be linked to improvements in data harmonization and service delivery. Ecuador’s social safety net policy at the beginning of the evaluation period was constrained by a fractured service delivery system characterized by poor coordination and inadequate data sharing between MIES and other government providers and within MIES itself. As such, the Social Safety Net Project includes a strong focus on data harmonization to reduce silo effects and strengthen the integration of service delivery with receipt of cash benefits. Progress toward these goals is ongoing, with achievements as of June 2023 documented as follows:

- Use of Social Registry data in MIES programs increased from 55 percent in 2019 to 95 percent in 2023.

- Use of administrative records to validate, update, and correct records in the Social Registry database increased from 43 percent in 2019 to 72 percent in 2023.

- By 2023, use of RUAD to assess exposure to climate-related risks had been completed for 55 percent of households in the Social Registry.

- The share of poor households with children under three years of age receiving BDH or BDH con Componente Variable and corresponding ECD services nationwide increased from 4 percent in 2019 to 16 percent in 2023.

- The share of extremely poor Indigenous older adult beneficiaries receiving Pensión para Adultos Mayores en Extrema Pobreza—Mis Mejores Años and older adult–care services increased from 6 percent in 2019 to 17 percent in 2023.

These achievements notwithstanding, low institutional capacity has reduced the World Bank’s effectiveness in improving social services. Since 2017, MIES has served as the nominal leader for Ecuador’s entire social safety net system.12 This has proved challenging for MIES staff, whose remit was historically limited to implementing specific programs, with little to no expertise in interagency coordination or multilateral development bank lending protocol. High levels of staff turnover exacerbate the situation, not least with respect to limiting the long-term value of trainings provided by the World Bank or other agencies.

The World Bank underestimated these capacity challenges in the design phase of the Social Safety Net Project. Although the Project Appraisal Document identified low institutional capacity as a substantial risk and included credible mitigating measures (World Bank 2019c), MIES-executed aspects of this operation have faced delays in procurement and staff hiring and inadequate documentation of expenditures and miscommunication regarding project processes and outcome indicators, with the latter frequently perceived by MIES staff as outside their institution’s authority to execute (World Bank 2021b, 2022b, 2022c).13 The World Bank attempted to address these issues by providing training and technical support regarding disbursement-linked indicators and procurement. Despite these efforts, inefficiencies in implementation have persisted. In addition, disagreement between MIES and the World Bank regarding the design and execution of the Crédito de Desarrollo Humano led to cancellation of a sustainability subcomponent on graduation (World Bank 2021a). This subcomponent included plans for a package of economic inclusion services designed to assist households that had exceeded BDH eligibility criteria and represented an important aspect of the project’s theory of change,14 underpinned by multiple diagnostics on vocational training and labor market inclusion.15

- As of 2015, contributory schemes reached approximately 40 percent of the country’s population (Apella and Zunino 2018).

- Interviews with World Bank, Ministry of Economic and Social Inclusion, and Secretaría Técnica de Ecuador Crece Sin Desnutrición Infantil staff.

- Child development centers, parent education groups (Creciendo con Nuestros Hijos), nutrition counseling programs (Círculos de Cuidado, Recreación y Aprendizaje), services for people with disabilities (Las Manuelas and Las Joaquinas), and senior citizens programs (day-care centers, home visits, and nursing homes).

- The Green and Resilient Recovery development policy operation (DPO) series.

- The Green and Resilient Recovery DPO series.

- The Inclusive and Sustainable Growth DPO series.

- The Inclusive and Sustainable Growth DPO series.

- The Bono 1000 Días cash transfer is linked to the Bono de Desarrollo Humano and aims to encourage the routine use of early childhood development services provided through the Ministry of Economic and Social Inclusion and growth monitoring, vaccination, and iron supplementation services provided through the Ministry of Public Health. It is also referred to as the Bono Infancia con Futuro.

- See also the Ecuador Child Development series and the Japan Social Development Fund: Growing with our GUAGUAS (Children).

- A significant reduction in stunted growth of children occurred at the province level during implementation of the Japan Social Development Fund: Growing with our GUAGUAS (Children) project, equivalent to a reduction in height-for-age Z score <2 of 2.5 percentage points per year. This was double the speed of the reduction of the stunted growth of children in the country as a whole at project close (Japan Social Development Fund: Growing with Our GUAGUAS [Children], November 2015 [TF098887]; World Bank 2018a).

- Unless otherwise noted, all statistics cited in this section are drawn from the disbursement-linked indicator matrix in World Bank (2023c).

- In 2017, the government reduced the Coordinating Ministry for Social Development’s reach by making it a technical secretariat of the Plan Toda una Vida. In 2021, under President Lasso, Independent Evaluation Group World Bank Group 91 the agency was transformed again to the Secretaría Técnica Ecuador Crece Sin Desnutrición Infantil, further reducing scope, such that its purview was limited exclusively to nutrition.

- In addition, interviews with World Bank and Ministry of Economic and Social Inclusion staff.

- See figure 1 in the Project Appraisal Document (World Bank 2019c).

- From 2013, the World Bank used diagnostics on vocational training and labor market inclusion to demonstrate how increasing the employability of Bono de Desarrollo Humano recipients would facilitate a sustainable exit strategy. Although these advisory services and analytics informed the graduation component of the Social Safety Net Project and the Interim Strategy Note, Country Engagement Note, and other World Bank documents, they failed to galvanize reform of the Crédito de Desarrollo Humano during the evaluation period.