The World Bank Group in Ecuador

Chapter 3 | Support for Ecuador’s Rebalancing to a Private Sector–Led Growth Model

Highlights

The government’s emphasis on private sector–led growth diminished during the 2007–17 period.

The World Bank Group supported Ecuador’s renewed focus on private sector–led growth after 2017 through policy support and direct investments in commercial banks and agribusiness firms.

The World Bank strategically focused on knowledge building during the 2007–17 period to make it “shovel ready” to support any eventual government transition to a more market-oriented and private sector–led approach to development.

After 2017, the World Bank provided a well-coordinated and comprehensive program to strengthen the country’s macroeconomic environment and expand the private sector’s role in the economy.

The International Finance Corporation took a systematic and relevant approach to supporting enterprise access to finance—a major constraint to the private sector. However, its investments in productive sectors were not grounded in an identification of the country’s needs related to the shift to a private sector–led growth model; thus, the International Finance Corporation may have missed opportunities to better contribute to this shift.

The World Bank’s private sector development support yielded early achievements in improving budget processes, expanding private sector access to credit, and improving market competitiveness by reducing tariffs and making it easier to create businesses.

In two reform areas—fuel subsidy reform and minimum wage reform—the World Bank’s suggested approach was not adopted or was adopted but subsequently reversed. In both cases, the World Bank failed to build the needed consensus and provide adequate technical support that would ensure understanding of the reform rationale to those tasked with their implementation and use.

The International Finance Corporation supported expanded small and medium enterprise access to finance and agribusiness growth, but it does not adequately track data to assess contributions to broader development outcomes, reducing its accountability.

Chapter Objectives and Methodology

This chapter assesses the relevance and effectiveness of Bank Group support for private sector development in Ecuador. The chapter considers the extent to which the Bank Group laid the foundation for later support when conditions for change presented, including by conducting relevant analytic work to inform the agenda. It also considers the support delivered in terms of its alignment with identified priorities (through diagnostic work). The effectiveness of the support considers the outcomes attributable to Bank Group support (drawing on results indicators used to monitor efficacy, if applicable). The chapter examines the Bank Group support both over the period from 2007 to 2017 of heightened state intervention and public investment and after 2017, the move to a more sustainable private sector–led growth development model. Bank Group support is evaluated according to (i) its relevance to recognized development priorities, in the context of the evolving partnership, and (ii) the effectiveness of the support (examining the Bank Group’s contributions to key objectives for the transition). The chapter finds that from 2007 to 2017 the World Bank built knowledge to be “shovel ready” should the government decide to transition to more of a private sector–led growth model and, after 2017, expanded this support to promote market competitiveness and high-potential growth sectors. However, the World Bank failed to ensure broad-based buy-in for energy subsidy and minimum wage reforms in the face of social opposition, leading to reform reversals.

Context of World Bank Group Support for Private Sector–Led Growth

The process of rebalancing toward a private sector–led growth in Ecuador has involved transition along two main fronts. On a first front, Ecuador has worked to address macroeconomic imbalances and a range of regulatory constraints that undermine private sector competitiveness and growth across the board. The World Bank’s FY18 SCD for Ecuador outlined three core policy agendas. On the macroeconomic front, the SCD highlighted an urgent need to bring the fiscal accounts to a sustainable position and rebuild fiscal buffers. On the trade and regulatory front, the SCD identified several challenges that had deterred greater private sector activity in Ecuador: (i) the lack of a coherent policy framework for private investment that reduces investor certainty and elevates costs; (ii) a complex and discretionary setting of the minimum wage; (iii) high costs associated with business regulatory compliance, including taxation; and (iv) trade restrictions and import tariffs that undermine competitiveness (World Bank 2018b). Outside of the trade and regulatory environment, significant distortions in the financial sector have reduced investor access to finance.

On a second front, Ecuador has aimed to encourage private investment in particularly high-potential growth sectors that have underperformed in the face of regulatory and other constraints. As part of its Plan de Prosperidad, the government of Ecuador has actively sought to attract foreign direct investment (FDI) that can facilitate Ecuador’s integration into regional and global markets. IFC’s FY21 Country Private Sector Diagnostic identified four sectors that demonstrate significant potential for greater participation from the private sector but that have been especially restrained by policy and regulatory constraints (both cross-cutting and specific to the sector). The four sectors—(i) medium- and large-scale mining; (ii) export of fruit, vegetables, and fisheries; (iii) transport and logistics for agriculture; and (iv) tourism—contribute in different ways to the government broader economic development goals (through jobs, export orientation, and links with the rest of the economy), and thus, special attention toward these sectors is viewed as potentially significant for the private sector–led growth transition (IFC 2021).

The Bank Group has supported Ecuador’s transition along both fronts. The World Bank provided early technical assistance over the FY07–17 period to identify core constraints to private sector competitiveness and growth. With a change in administration in 2017, the World Bank shifted its support from purely technical knowledge to policy-based finance targeting public sector efficiency and fiscal sustainability and the removal of key regulatory and financial sector barriers to private sector development. IFC support included both early advisory work at the municipal level to support regulatory simplification and advisory support and investment finance to banks and agribusiness firms. IFC support to banks aimed to expand access to credit to small and medium enterprises (SMEs) and enable exporter access to international markets, whereas its investments in the agribusiness sector sought to expand market position and access to global markets and to support access to nutritious food across the country.

World Bank Group Private Sector–Led Growth Support from 2007 to 2017

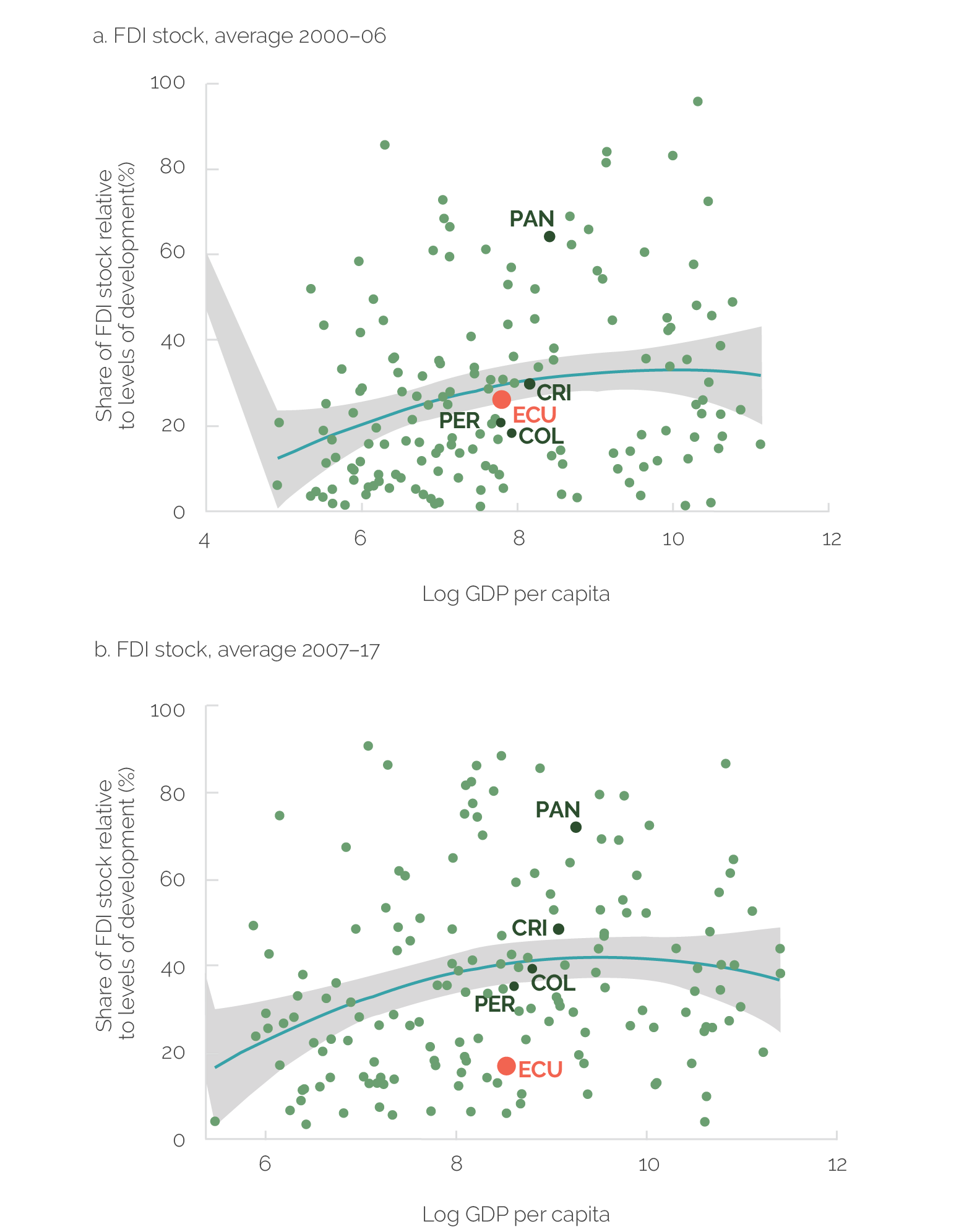

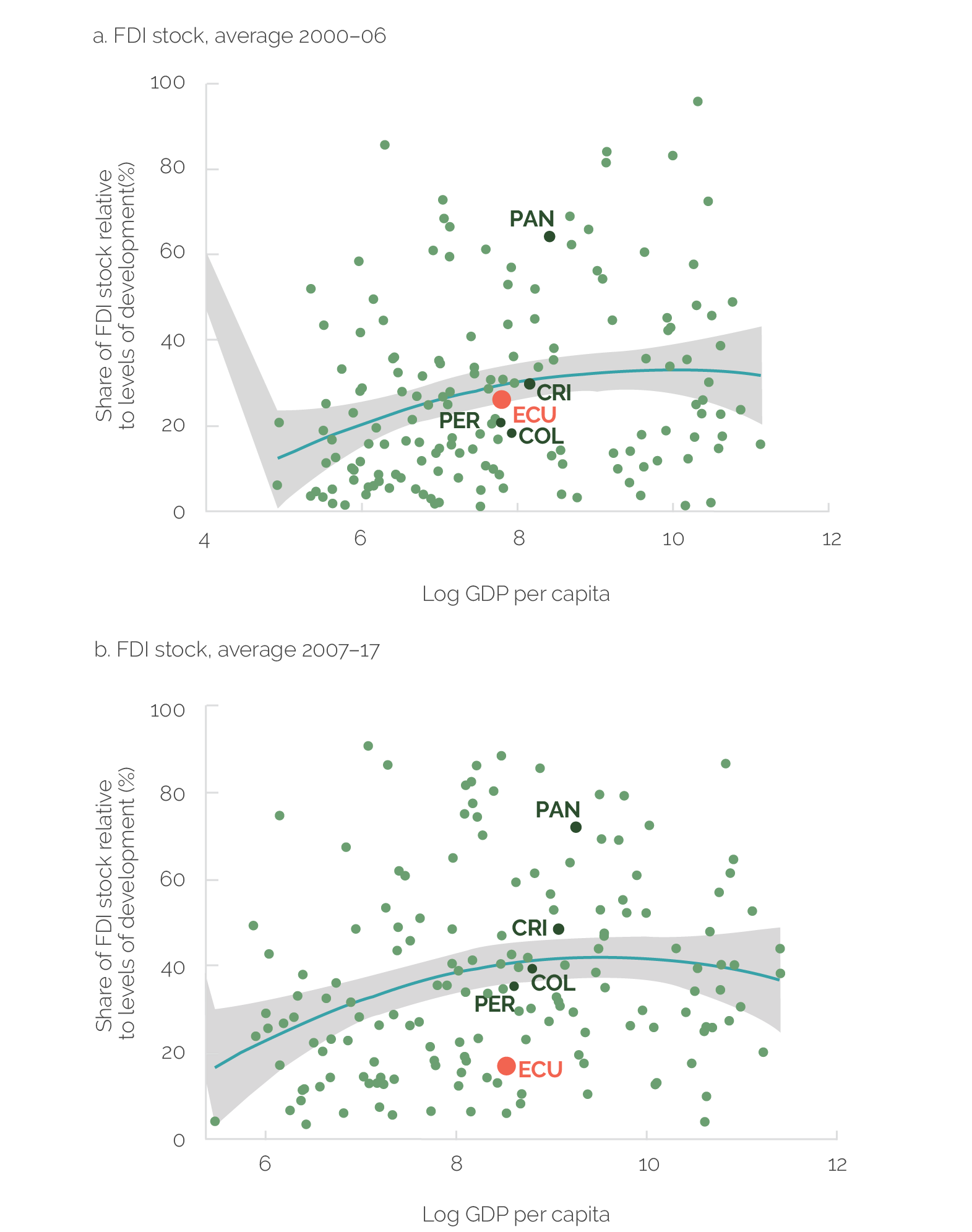

Ecuador’s private sector showed increasing signs of strain over the 2007–17 period. By many indicators, Ecuador’s private sector was weakened over the Buen Vivir period starting in 2007. Private investment as a share of GDP had declined from 16.6 percent in 2006 to 13.9 percent in 2014. Annual FDI had also fallen from an average of 2.0 percent of GDP between 2001 and 2006 to an average of 0.6 percent between 2009 and 2014, making Ecuador’s FDI rate the lowest in the region (World Bank 2018b). Relative to its level of development, Ecuador’s FDI stock declined sharply from the 2000–06 to the 2007–17 period, whereas its peers either maintained their FDI stocks or gained ground (figure 3.1).

Figure 3.1. Foreign Direct Investment Stock Relative to Levels of Development, 2000–06 versus 2007–17

Source: International Finance Corporation 2021.

Note: COL = Colombia; CRI = Costa Rica; ECU = Ecuador; FDI = foreign direct investment; PAN = Panama; PER = Peru.

Several factors contributed to weak private sector growth in Ecuador. Various diagnostics point to key obstacles to private investment and growth (IFC 2021; World Bank 2011, 2017a). Among them are the following:

- Frequent economic, commercial, and investment policy changes created a layer of uncertainty for investors, affecting incentives to engage in long-term projects.

- Access to finance by firms is hindered by a shallow financial sector that is constrained from playing its role as an intermediary in support of the private sector. The financial sector is dominated by banks and credit cooperatives, and the framework for financial sector oversight is complex and uncoordinated, reducing banks’ ability to lend and shifting the allocation of credit away from more productive purposes toward consumer lending (World Bank 2018b).

- Trade and investment regulations, from insolvency procedures to taxation to licensing, inhibit firm entry and operations.

- The framework for public-private partnerships has made it difficult to structure tenders that are bankable, transparent, and competitive.

- Labor productivity is low and has not kept pace with wage increases. One factor contributing to a lack of correspondence between productivity increases and wage increases was the process for setting minimum wages, which was complex (including a national minimum wage and minimum wages by 21 sectors and across 2,300 occupations) and not evidence based. The minimum wages reflected a bargaining process between workers, employers, and government representatives, but when no agreement was reached, the minimum wage was set by the Ministry of Labor, resulting in divergent minimum wages for similar occupations and not reflecting differences in productivity within and across sectors and firms (figure 3.2).

Figure 3.2. Minimum Wage Relative to Value Added per Worker in Ecuador, 2007–17

Source: World Bank 2018b.

In addition, the development model was no longer fiscally viable. The commodity boom allowed for sizable public spending increases, but when oil prices fell, Ecuador faced increasing fiscal strains. High fiscal deficits and weak growth prospects led to a rapid rise in government debt from 19.2 percent of GDP in 2010 to 46.1 percent in 2019 and 61 percent in 2021 (IMF 2019a, 2021).

The World Bank’s support for fiscal sustainability and private sector–led growth responded to two distinct political economy settings. The World Bank’s engagement over the 2007–17 period was affected both by the rupture in dialogue with the government of Ecuador and by a fundamentally altered development model (relative to the prior administration, which guided World Bank support under the Country Assistance Strategy 2003–07 cycle). As a result, the World Bank’s strategy of support for a fiscally sustainable, private sector–led growth model went through two distinct stages: (i) over the Correa administration, where the focus was on building dialogue and knowledge, and (ii) after 2017, where the World Bank’s focus was on supporting the new government’s wide-ranging reform agenda.

The World Bank’s support during the 2007–17 period focused narrowly on building knowledge. With limited avenues established, the World Bank used NLTA on a few diverse topics to keep abreast of economic developments and mitigate information gaps. Early activities did not provide comprehensive assessments of policy but laid a foundation of knowledge that could mitigate information gaps. Later analytic work tackled broader policy questions, bringing together the established analysis.

Several of these early analytic pieces built knowledge on constraints facing the private sector. For example, the World Bank undertook two studies to understand dynamics of informality, both at the firm level and at the labor force level. The early work would be extended with subsequent analytic work in conjunction with the National Institute of Statistics and Census (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censos) and would create important knowledge on the role that the minimum wage played in reducing formal sector employment (and increasing informality), among others.

The World Bank effectively filled knowledge gaps through development partnerships. For example, World Bank and IMF staff had limited confidence in official statistics provided by the Ministry of Economy and Finance and the Central Bank of Ecuador;1 therefore, staff from both institutions organized a high-level working group to discuss and evaluate Ecuador’s macroeconomic developments. The working group included actors from other development banks and from the private sector and academia (for example, the chief economists of large private banks).2 This allowed the World Bank to fill information gaps from official channels and remain informed on emerging challenges.

The World Bank leveraged its dialogue with MCPEC to analyze constraints to Ecuador’s firm productivity. After the passage of the 2010 Organic Code of Production, Commerce, and Investment, MCPEC was tasked with implementing Ecuador’s transformation of the productive matrix. The main goal was to transform production away from natural resources and imports and to incentivize local production and systems of innovation and entrepreneurship. MCPEC reached out to the World Bank to provide limited analytic work on select subjects. Over the FY12–17 period, the World Bank expanded its range of analytic work to fill knowledge gaps on Ecuador’s trade and investment dynamics. The World Bank’s earliest work on informality (assessing aspects of the regulatory framework affecting firms’ formality, their access to finance, and their growth potential) broadened to cover innovation policy. The growing dialogue led to the first reimbursable advisory services to the government of Ecuador to examine the role of services in competitiveness and to inform policies for service sector innovation, their integration into export-oriented global value chains, and trade competitiveness through services. Further work on global value chains investigated constraints to greater global value chain integration and identified untapped global value chain opportunities. The analytic work ultimately led to the preparation of a Country Economic Memorandum in 2016, providing the core knowledge base from which to support the incoming administration in 2017.

Starting in FY17, the World Bank developed technical notes to inform the incoming administration on economic priorities. The World Bank presented a series of policy notes to the new government on fiscal policy, productivity and diversification, social protection, labor costs, labor inclusion, and financial sector stability. The World Bank used that knowledge base to draft its SCD (delivered in June 2018), which became the starting point for the World Bank’s operational support starting in FY19. The Bank Group further strengthened analytic work after the SCD, undertaking a flagship report aimed at synthesizing the main macroeconomic stability and competitiveness challenges (World Bank Group 2019). The report wove together four related pieces of diagnostic work: (i) Ecuador—Public Finance Review: Phase II (World Bank 2019b); (ii) Public Investment Management Technical Assistance; (iii) Financial Stability and Inclusion ASA; and (iv) Trade, Investment, and Competitiveness ASA. Simultaneously, IFC and the World Bank jointly initiated a Country Private Sector Diagnostic (delivered in FY21).

After 2007, IFC focused on the financial and agribusiness sectors. In 2005, IFC launched the Global Trade Finance Program (GTFP), which supported participating banks’ access to international corresponding banks,3 important for enabling trade finance to flow in the country, particularly under fluctuating macroeconomic conditions and at times high country risk. IFC added three Ecuadoran banks to its GTFP over 2007 and one in FY08.4 This was IFC’s first substantial engagement in Ecuador’s commercial financial sector—an engagement that IFC would build on over time.

Over the same period, IFC provided advisory services to support regulatory simplification at the municipal level. In 2006–09, IFC supported the municipalities of Manta and Quito to simplify the processes for obtaining an operating license and a construction permit. This project was coordinated with a semiautonomous agency under MCPEC. Based on the success of this activity, subsequent advisory services were undertaken in 2009–13 that expanded the work to four additional municipalities (Guayaquil, Cuenca, Loja, and Zamora).

World Bank Group Private Sector–Led Growth Support after 2017

A new government in 2017 sought comprehensive support from the World Bank to navigate a new development model. Although President Lenín Moreno was elected under the auspices of his predecessor’s political movement, his government quickly distanced itself from the prior government’s policy stance, seeking to reduce the state’s footprint on the economy, restore fiscal sustainability, and create space for the private sector to expand. The new government of Ecuador reached out to the World Bank and IMF for both financing and guidance on fiscal consolidation.

The Bank Group’s support toward the government reform agenda was developed under the CPF for FY19–23. The CPF foresaw Bank Group assistance (i) supporting fundamentals of inclusive growth by addressing macroeconomic imbalances, removing barriers to private sector activity, and enabling the financial sector to better intermediate the allocation of resources to productive use; (ii) boosting human capital and protecting the vulnerable by improving access to basic services and quality education, addressing malnutrition, and protecting the vulnerable through well-targeted social programs; and (iii) enhancing institutional and environmental sustainability by bolstering the ability for the public sector to make effective decisions based on solid evidence.

The World Bank used two programmatic DPO series to support the government transition to a private sector–led growth model. The first programmatic series—the Inclusive and Sustainable Growth development policy loan series (FY19, FY20, and FY21)—was prepared to support a major transition to a more market-oriented and private sector–led approach to development. The DPO series (undertaken in parallel with a $4.2 billion arrangement under IMF’s Extended Fund Facility) centered on three main pillars: (i) reducing the barriers to private sector development, (ii) promoting public sector efficiency and fiscal sustainability, and (iii) protecting poor and the most vulnerable people. The second DPO programmatic series—the Green and Resilient Recovery development policy loan series (FY22)—supported improved tax revenue collection and reduced trade barriers to support global integration, among others. The DPO series, along with an investment finance operation to improve firm access to finance (Promoting Access to Finance for Productive Purposes for MSMEs, FY21), allowed the World Bank to support reforms across three areas.

The DPO series and a financial sector IPF would also support broader reforms to remove fiscal and competitiveness constraints in Ecuador. Through the DPO series, along with an investment finance operation to improve firm access to finance (Promoting Access to Finance for Productive Purposes for MSMEs, FY21), the World Bank supported reforms across areas that constituted important barriers to fiscal sustainability and private sector–led growth.

First, the World Bank supported reforms to promote public sector efficiency and fiscal sustainability. These included the following:

- Reforms oriented toward improved budget control and fiscal discipline (including strengthened budget preparation processes, the adoption of a medium-term fiscal framework, and improved oversight and mitigation of fiscal risks)

- Reforms toward improved procurement processes, expanding the use of competitive processes

- Elimination of public sector staff redundancies

- Improved taxpayer compliance and elimination of select personal income tax expenditures

- Energy subsidy reform aimed at rationalizing and reducing fossil fuel subsidies, thereby offsetting their negative impact on fiscal sustainability

Second, the World Bank supported reforms to improve private sector investment and competitiveness. The DPO series supported a range of reforms that together accounted for significant barriers to private investment. These reforms included the following:

- A revision of the legal code to require the inclusion of international arbitration clauses on large contracts, paving the way for Ecuador to also rejoin the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) and signaling to foreign investors the government’s commitment to protect their investments

- A reduction in tariffs and nontariff barriers on intermediate inputs that adversely affected Ecuador’s export competitiveness, value added, and total factor productivity growth

- Facilitation of enterprise creation, including through enhanced use of limited liability modality for firms, simplified regimes for registering a company, and simplified procedures for import

- Minimum wage reform, reducing the number of sectoral minimum wages (estimated at 2,300 in 2018) by 5 percent a year (and setting a timeline toward a universal minimum per sector) and providing an objective, productivity-based formula for wage increases when tripartite negotiations failed

Third, the World Bank supported reforms to enhance access to finance for firms, particularly MSMEs. Through the Inclusive and Sustainable Growth DPO series, the World Bank supported government actions to enhance financial market efficiency through four main actions:

- Supporting reforms to reduce financial distortions by consolidating credit segments and adopting flexible rate ceilings toward a gradual interest rate liberalization

- Supporting reforms to eliminate central bank financing of public banks, in the process not only limiting quasi-fiscal operations but also helping level the playing field in terms of costs of funding between private and public banks

- Supporting an increase in the effective liquidity of commercial banks through revisions to the interpretation of liquidity requirements

- Supporting reforms to allow remote account opening, including via mobile phone, facilitating access to finance

The World Bank also supported SME access to finance through an investment project and ASA. Public banks traditionally had responded to gaps left by private banks in the MSME segment, but in the presence of fiscal constraints (most importantly over the COVID-19 pandemic), public banks had fewer resources. Through the Promoting Access to Finance for Productive Purposes for MSMEs IPF, the World Bank supported a strengthening of the institutional capacity of the Corporación Financiera Nacional (CFN)—Ecuador’s largest public bank. In addition, it helped CFN develop new or improved existing financial products to promote access to finance for productive purposes, especially MSMEs. The project supported CFN’s establishment of second-tier lending operations to the commercial and cooperative sector to serve MSMEs. The World Bank also provided ASA toward financial inclusion, undertaken through the Ecuador Financial Stability and Inclusion ASA and the Ecuador Financial Inclusion FIRST Project (an advisory project).

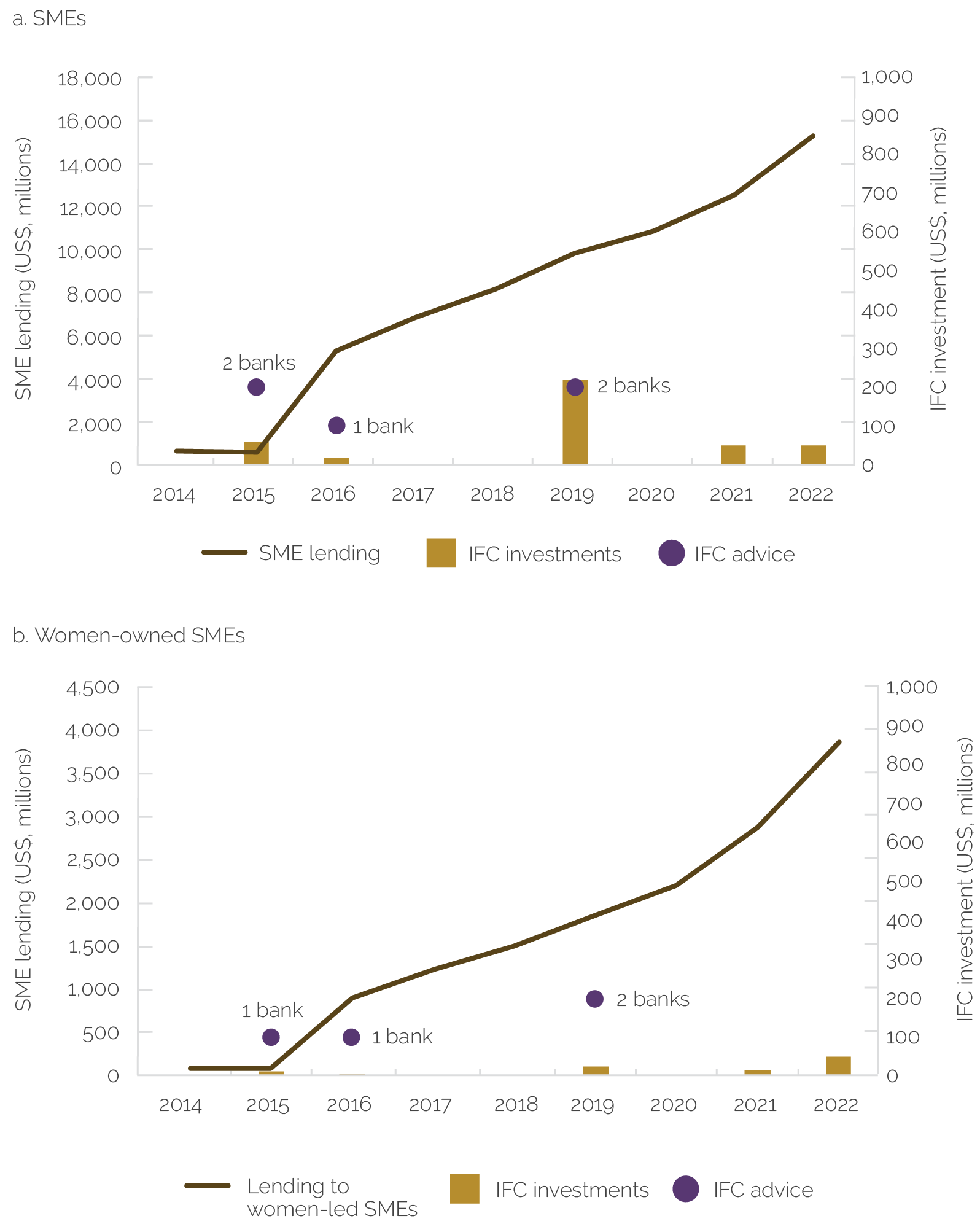

IFC supported Ecuador’s financial sector through an evolving stream of investments and advisory support. Starting in 2014, having developed relationships with banks through the GTFP, IFC moved into supporting the banks’ operations for lending to SMEs, including women-owned SMEs and some support for “climate-smart” projects. IFC lent $150 million to four of Ecuador’s largest banks for these purposes from 2015 through mid-2017. IFC also provided knowledge, helping banks develop and grow their business with women-owned SMEs and energy efficiency. IFC’s relationships with these banks continued to grow in the 2017–22 period, with $360 million in investment.

IFC’s investments in agribusiness aimed to help market leaders expand. IFC invested in market leaders in dairy, pork and poultry, shrimp, and bananas, aiming to help firms expand production and distribution, upgrade environmental standards, improve energy efficiency, and make other improvements. In addition to investment finance, IFC provided support to clients (at times through advisory services but also as part of its standard monitoring processes) to identify risks and establish strategies for mitigating them and to improve monitoring systems and social and environmental standards.

Relevance of World Bank Group Support

World Bank

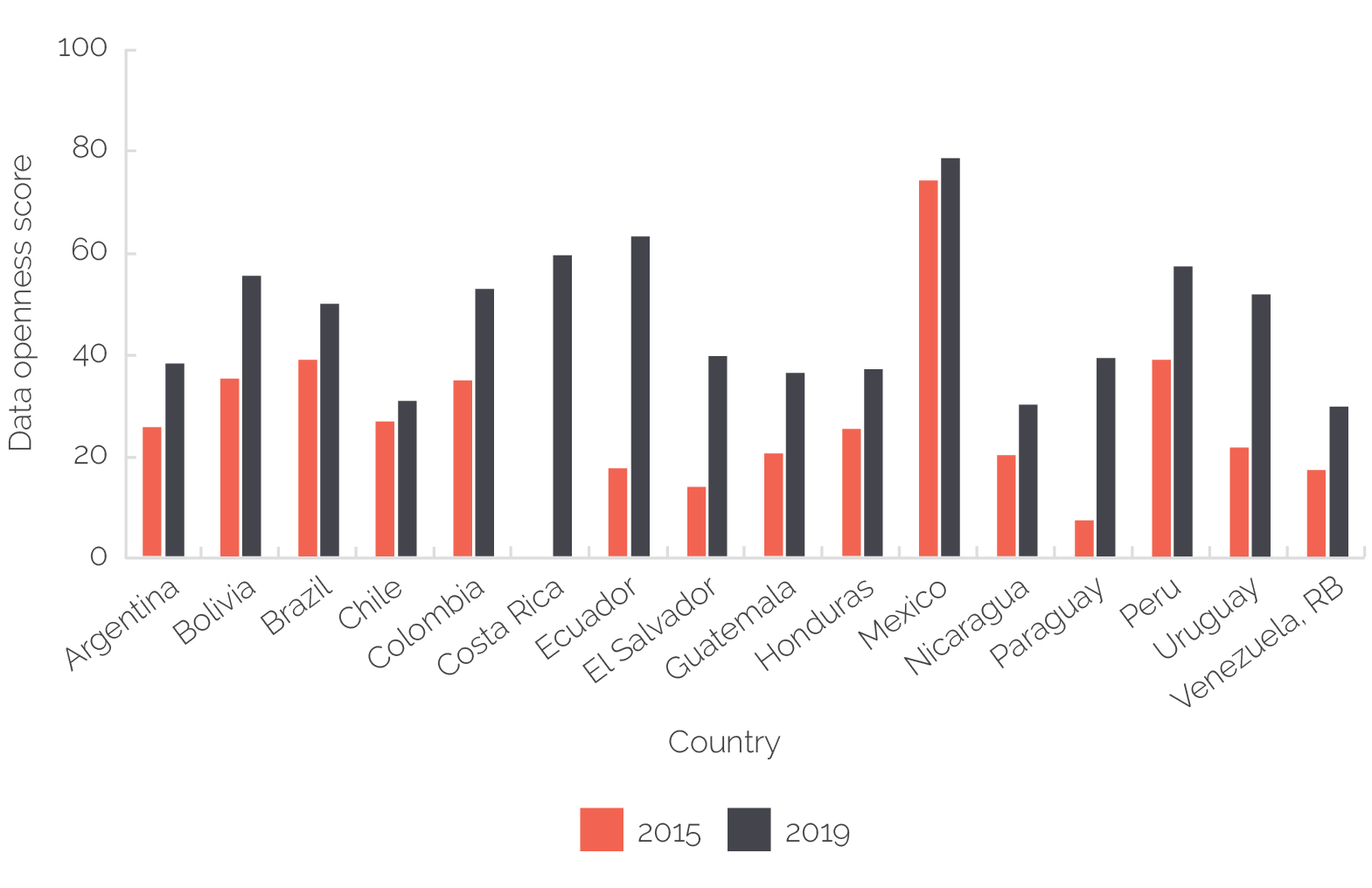

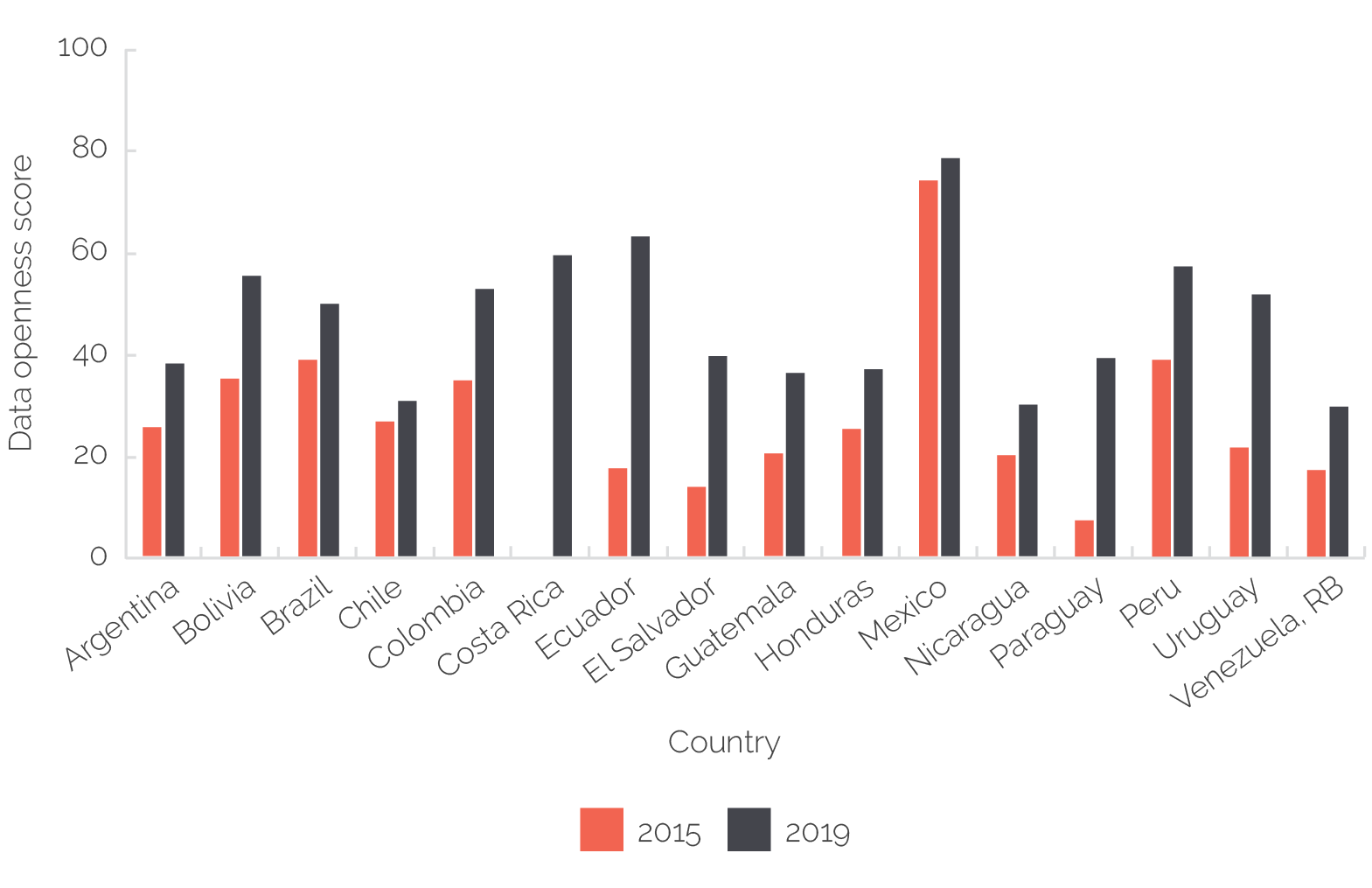

The World Bank’s early focus on ASA was relevant to the context, filling information gaps to inform future engagement. Over the periods of limited activity and operational reengagement (2007–17), Ecuador’s data transparency was low. According to the Open Data Inventory, which assesses the coverage and openness of official statistics, Ecuador ranked near the bottom of all Latin American countries in 2015, with significant problems in access to key data—a situation that was significantly improved after the change in government (figure 3.3). The World Bank’s analytic work over both periods and its coordination with other development partners used narrow windows of dialogue both to strengthen engagement and to fill information gaps for future policy support.

Figure 3.3. Open Data Openness Score: Latin American Countries, 2015 and 2019

Source: Open Data Inventory (database), Open Data Watch.

Note: The data openness score is based on data gaps and open data policies in 22 topical data categories grouped as social statistics, economic and financial statistics, and environmental statistics. The overall score reflects how well a country’s data offerings meet international standards of openness. RB = República Bolivariana.

The World Bank’s subsequent operational support starting in FY19 was relevant for restoring investor confidence and helping guide a credible policy agenda. Interviews with the Ministry of Economy and Finance suggest that the World Bank’s support was critical to the government reform program for two reasons. First, the World Bank and IMF played an instrumental role in building credibility for the government reform agenda among the international community, which was vital to preserve dollarization and recover macroeconomic fundamentals. In 2018, the government of Ecuador was actively seeking to improve ties with US banks and multilateral lenders as means to address the rapidly deteriorating fiscal situation. The “stamp of approval” on Ecuador’s reform agenda by the World Bank and IMF in particular was viewed as instrumental for the later bond repurchase agreement the government negotiated with Goldman Sachs. Second, and as important, the World Bank’s technical staff guided key aspects of government reform agenda—one that included efforts to increase efficiency in the mobilization and allocation of government resources, to eliminate barriers hindering private sector development, and to improve protection of Ecuador’s most vulnerable population groups.

The World Bank–supported reforms undertaken by the government of Ecuador were informed by a breadth of analytic work.

- Fiscal reforms: The government of Ecuador’s subsidy reform agenda was informed by early distributional analysis on subsidies undertaken by the World Bank. The elimination of staff redundancies in deconcentrated offices responded to a growing public sector wage bill identified in the Ecuador—Public Finance Review (2018) and reflected an appropriate way to reduce costs without adversely affecting service delivery. Reforms toward improved budget control, fiscal discipline, and fiscal risks assessment emanated from priorities identified in the Ecuador—Public Finance Review (2018), which stated that the major budgetary challenges were absence of “budget preparation procedures and milestones that ensure consistency between the macro-fiscal programming exercise and the annual budget programming” (with a more than 20 percent deviation between approved and executed budgets); weak multiyear planning; and “a bottom[-]up approach with no aggregate, sectoral, or institutional ceilings” (World Bank 2024a, 13).

- Trade and regulatory reforms: The removal of restrictions on international arbitration clauses was highlighted in both the SCD and the Country Private Sector Diagnostic as key to reducing perceived risks of investing in Ecuador, which at the time of the DPO series were particularly affecting private participation in the oil and infrastructure sectors. The reduction of tariffs and nontariff barriers undertaken in the context of the World Bank’s Green and Resilient Recovery DPO targeted intermediate inputs that would have the highest immediate impact on productivity (and competitiveness), drawing in part on analytic work that showed that the shift from domestic intermediate inputs to imported inputs would increase Ecuador’s manufacturing firm productivity by 7 percent. Similar analytic work underpinned other World Bank–supported reforms. The Inclusive and Sustainable Growth DPO series drew on more than 30 analytic activities and advisory tasks that set forth the priorities and challenges for transition from a state-led to a more market-oriented development strategy, the majority of which also underpinned the 2018 Systemic Country Diagnostic. Design of the series also drew on the 2018 and 2019 Public Finance Reviews; the 2019 Trade, Investment, and Competitiveness diagnostic; and the Energy Sector Management Assistance Program study on sustainable and equitable energy subsidy reforms in Ecuador (2018–20), among others.

- Financial sector reforms: The World Bank–supported financial sector reforms addressed known constraints to access to finance. Fixed interest rate caps across all credit segments prevented lending to new or riskier borrowers, diverting resources to consumer lending, which is less constrained. Under the Inclusive and Sustainable Growth DPO series, the World Bank supported initial steps for interest rate flexibilization and transparency, by revising the criteria for determining the ceilings in different credit segments and by consolidating the credit segments. The action was expected to reduce opacity and increase flexibility in interest rate ceilings. Even though the action reflects a meaningful step toward interest rate liberalization, interest rates need to converge to market clearing rates across all credit segments. The World Bank’s support toward strengthening CFN, although not an identified constraint to financial access, remains relevant to expanding financial access to MSMEs. As with IFC support to financial institutions, the World Bank’s support to CFN allows participating financial institutions to expand their ability to service MSMEs through technical assistance, designated credit lines, and partial credit guarantees.

The World Bank closely coordinated its support with development partners. The World Bank–supported Inclusive and Sustainable Growth DPO series was complemented by a three-year Extended Fund Facility by IMF and financing packages from CAF, IDB, and the Latin American Reserve Fund. With regard to content, World Bank support toward fiscal sustainability and private sector–oriented regulatory reform under the Inclusive and Sustainable Growth DPO series and the Green and Resilient Recovery DPO series was part of a package of coordinated financial assistance from Ecuador’s main international partners: IMF, the World Bank, IDB, and CAF. Staff of the institutions met regularly to align messages and coordinate efforts, and there was a high degree of complementarity among the programs,5 with IMF focusing on improving the fiscal framework and strengthening the credibility of the dollarization regime and the World Bank supporting efficiency gains in the allocation of government resources, structural reforms to foster private sector developments, and improvements in social protection and inclusion. There was an effort to ensure no overlap of specific measures supported in the development policy financing series with either the structural benchmarks in the IMF program or the prior actions included in the IDB and CAF operations (table 3.1).

Table 3.1. Coordinations of World Bank Group Support to Private Sector Agenda with Multilateral Financial Institutions

|

Reform Area |

World Bank |

IMF |

IDB |

Other |

|

1. Private sector and private investment |

• |

• |

||

|

• |

• |

||

|

• |

• |

||

|

||||

|

||||

|

• |

|||

|

• |

• |

||

|

• |

• |

||

|

2. Labor reform |

• |

|||

|

3. Financial sector |

• |

• |

• |

|

|

• |

• |

• |

|

|

||||

|

• |

|||

|

• |

|||

|

||||

|

4. International trade |

• |

• |

• |

|

|

• |

CAF |

||

|

• |

|||

|

• |

|||

|

||||

|

5. State-owned enterprise reform |

• |

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: CAF = Banco de Desarrollo de América Latina y el Caribe; IDB = Inter-American Development Bank; IMF = International Monetary Fund.

IFC’s support to the financial sector was relevant to SME financing needs. Lack of access to finance was a major constraint to the private sector. IFC’s financing enabled exporters to access international markets through trade finance, the need for which was particularly acute in the earlier part of the evaluation period and that remained strong through the period. IFC expanded banks’ capacity to lend to SMEs, with a focus on women-owned SMEs, particularly with loans of longer tenor than were available from domestic banks.

IFC’s agribusiness support was relevant to promoting economic growth and improving conditions for poor people. Agribusiness is a major engine of the country’s economy and export competitiveness. Loans at tenors offered by IFC (and in one case, the amount provided by IFC) were not available on the domestic market. IFC’s activities were also relevant to improving conditions for poor people, reaching farmers and small suppliers (upstream), and lower-income consumers across the country through access to nutritional food (downstream). IFC’s advisory services to food production companies in partnership with the Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition helped develop fortified food products for infants and children 6–24 months of age, targeted to low-income households.

However, apart from the financial sector, IFC did not take a strategic approach to alleviating the private sector’s constraints to growth or systematically promoting opportunities for growth. This was partially because of the substantial political and economic risk perceived by IFC, which led IFC to take a cautious approach. The ISN and CEN kept the scope of IFC’s possible investments very broad. In the real sector, IFC financed companies with strong sponsors in sectors with low perceived regulatory risk, and each project that IFC financed had a plausible development outcome (as discussed in this section). However, as seen in projects’ Board approval documents, IFC did not ground its support in an understanding of needs or a theory of change related to the shift to a private sector–led growth model. Although the CPF established that IFC would focus on export-oriented agribusiness and energy (the latter as appropriate conditions are established), only one of IFC’s clients in FY19–22 was primarily export oriented (this investment represented just under 20 percent of IFC’s net commitments in the nonfinancial sector during that time). IFC did not have its own Country Strategy for Ecuador. Unlike in the financial sector, IFC did not take a strategic approach to supporting industries or themes (for example, participation in global or regional value chains) in the real sector. Diagnostics and a more strategic approach may have been useful even in a risky context. Thus, IFC may have missed opportunities to better contribute to the shift to a private sector–led growth model.

Effectiveness of World Bank Group Support

The World Bank’s support for increasing the private sector’s access to credit delivered important achievements. The World Bank–supported government actions to increase interest rate flexibility, reduce barriers to digital financial services, and increase bank liquidity through the Inclusive and Sustainable Growth DPO series contributed to an expansion of credit to the private sector from 34.3 percent of GDP in 2017 to 48.8 percent in 2022, although it is not possible to link the increase solely to the World Bank–supported reform agenda, within the context of a range of market-oriented reforms. Credit to MSMEs has also expanded, aided by the World Bank’s support for restructuring CFN and the development of credit lines for second-tier lenders toward beneficiary MSMEs. After the World Bank’s FY21 Promoting Access to Finance for Productive Purposes for MSMEs IPF, approximately $272.9 million was disbursed to 20 participating financial institutions for onlending to MSMEs. Of this amount, the participating financial institutions have already on-lent $99.1 million to final beneficiaries, corresponding to 3,738 loans. Although not direct evidence of increased investment, these achievements reflect reasonable steps in the results chain to enhanced access to credit by the private sector.

The World Bank’s support facilitated the entry of new firms into the domestic market. The World Bank’s support to facilitate enterprise creation contributed to an increase in the number of formal commercial companies registered from 8,200 to more than 22,000 by 2022 (five times the increase targeted through the Inclusive and Sustainable Growth DPO series). Other positive results from this action included increased tax revenues from these businesses and increased participation of women as owners and employees.

The World Bank contributed to the government reducing tariffs on intermediate inputs, thereby increasing the competitiveness of domestic exporters. The World Bank supported tariff reforms under the same Inclusive and Sustainable Growth DPO series. As a result of these reforms, the share of capital and intermediate inputs in agriculture and technology subject to reduced tariff rates increased from 12 percent in 2017 to 24 percent in 2022 (doubling the targeted change). This represented a notable step toward the longer-term outcome of improved international competitiveness of domestic exporters.

The World Bank’s support contributed to several improvements in government budget processes that reduce fiscal risks. Reforms toward budgetary preparation processes undertaken in connection with the Inclusive and Sustainable Growth DPO series supported a reduction in divergences between approved and executed budgets from 16.3 percent in 2017 to 8 percent by 2022. The improvement in budgetary processes could reasonably be expected to support improved budget control, fiscal discipline, and assessment of fiscal risks in the medium term, toward the objective of improved fiscal sustainability.

The World Bank–supported energy and minimum wage reforms were reversed by the government. Although the Inclusive and Sustainable Growth DPO series supported reforms to energy subsidies and minimum wage increases, these reforms were partially or fully reversed. In the case of energy subsidy reform, the reforms undertaken led to large oil price increases that triggered violent protests and a subsequent reversal. The fuel subsidy reform agenda was revised over the third DPO toward more gradual removal of gasoline and diesel subsidies, while establishing a price smoothing formula to protect consumers from excessive price volatility. In the case of the minimum wage reform, the World Bank had supported a revision to the formal minimum wage setting process, providing an objective, productivity-based formula for setting minimum wages when tripartite negotiations (between unions, employers, and the government) failed. However, the reform was reversed by executive action.

The World Bank did not ensure government buy-in for an incremental approach to energy subsidy reforms. During the preparation of the First Inclusive and Sustainable Growth DPO, the World Bank recommended a gradual process for fuel subsidy reform based on prior incidence analysis.6 The World Bank provided extensive technical support to the government to steer its reform agenda, including technical reports on cost recovery and distributional impacts of subsidies and just in time technical support on compensation mechanisms for subsidy removal. Based in part on that support, Ecuador eliminated high-quality gasoline subsidies (super) and in December 2018 increased the price of gasoline. However, in October 2019, the government eliminated gasoline subsidies entirely. Although this action was not officially part of the DPO series discussions, the government’s decision points to a failure in adequately communicating and building consensus within the government of Ecuador on the need for an incremental approach to the reforms. The government’s desire to use its narrow political window to implement reform resulted in the government implementing a bolder set of fuel subsidy reforms that brought on widespread social protests.7 These protests led to the ultimate reversal of these reforms. Since then, through the support of the development policy financing series, the government adopted a price smoothing formula that was applied without interruption until October 2021, and the price of gasoline has made progress in converging toward international prices.

Inadequate technical assistance undermined minimum wage reforms. The World Bank supported the government of Ecuador’s revision to the minimum wage setting process, including through a reduction in the number of sectoral and occupational minimum wages (from over 2,000) and the adoption of an objective, productivity-based formula for setting minimum wages when tripartite negotiations failed. If sustained, the minimum wage setting mechanism could better align labor costs with productivity to help firms remain competitive. The reform was implemented in 2020, but the continued use of the formula was interrupted when the new administration announced minimum wage increases of $25 per year over President Lasso’s term. The continued use of the formula depended on a deep consensus building within the country, with adequate understanding of its rationale and sufficient technical support toward the three parties tasked with its use (the Ministry of Labor, the Chamber of Industries and Production, and labor unions). Insufficient reform championing and technical assistance to the involved actors hindered that consensus building internally and the reform’s continued uptake. At the same time, since 2023, the current administration has resumed the minimum wage salary setting in compliance with the legal instrument supported by the World Bank.

IFC’s early advisory services helped simplify certain municipal-level processes. IFC’s 2006–09 support to the municipalities of Manta and Quito to simplify the processes for obtaining an operating license and a construction permit led to combined cost savings for businesses of $3.4 million against a target of $1.6 million. The subsequent advisory services in 2009–13 expanded the work to four more municipalities (Guayaquil, Cuenca, Loja, and Zamora). The project simplified procedures, substantially reduced the time to obtain an operating license (94 percent reduction) and construction permit (67 percent reduction), and saved businesses $3.7 million; however, these savings fell short of the target.

IFC’s support also improved SME access to trade finance through financing and knowledge. The GTFP program played a key role in bank access to international corresponding banks,8 and when IFC moved into longer-term finance, its investment enabled banks to extend loans of longer tenor than were available with domestic resources and to improve financial products and management. This includes products and methodologies for lending to women-owned SMEs, for energy efficiency, and for enhanced portfolio monitoring of gender aspects. Overall, IEG estimates that over the evaluation period, IFC lent $558 million to banks for lending to SMEs and $216.5 million for lending to women-led SMEs.

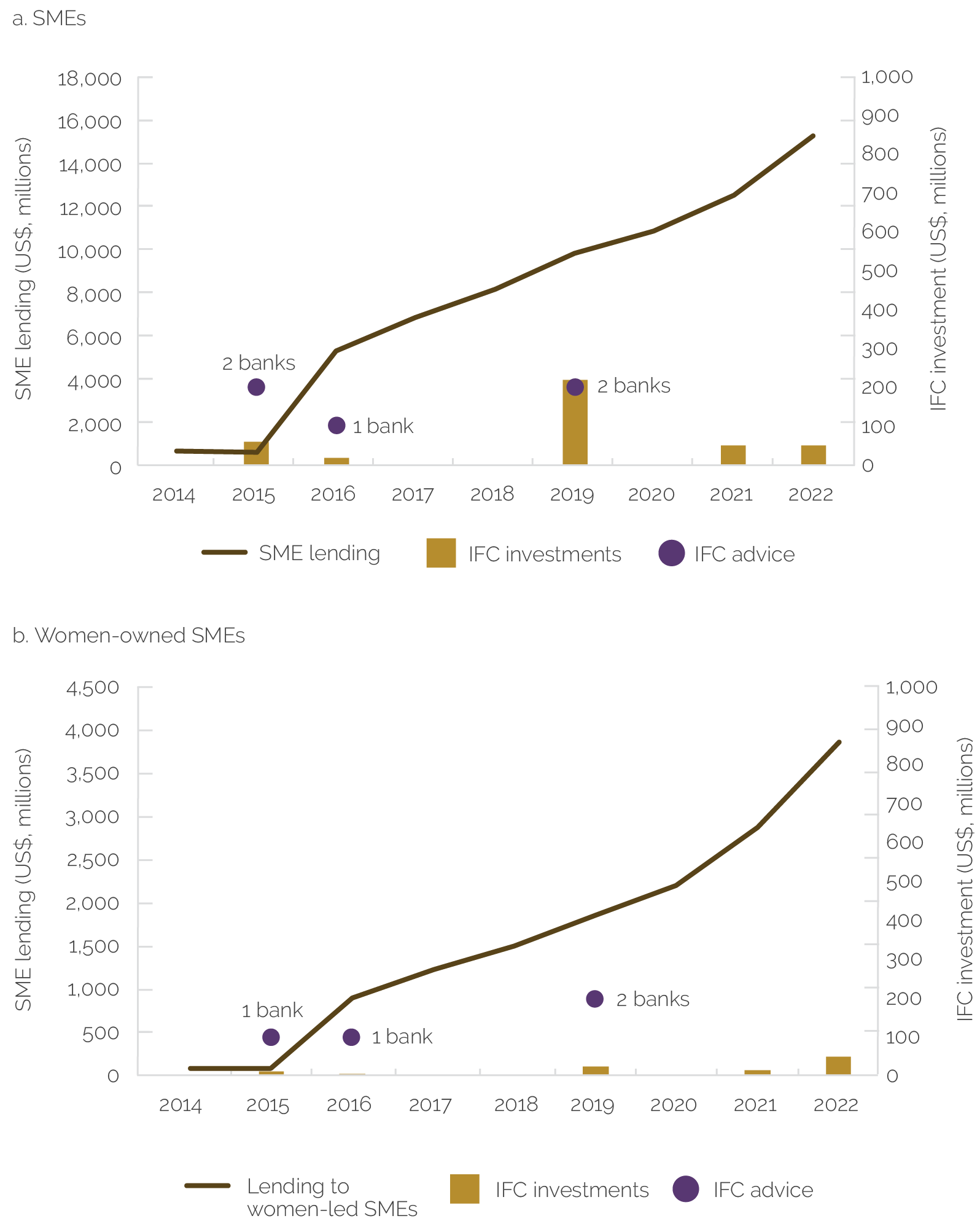

Although IFC made a plausible contribution to access to finance in these areas, its monitoring was insufficient to quantify its contribution. Despite the apparent success of its activities in the financial sector, there were gaps in IFC’s monitoring, with data on actual lending by purpose (SME or women-led SME) some clients in some years. Few data were reported on outputs or outcomes of climate finance.9 Although some of its clients were already active in the areas supported, lending in each of these segments experienced substantial growth after IFC investment and advice. Figure 3.4 outlines how the portfolios of three of IFC’s four client banks in Ecuador have grown over time, along with IFC investment and advice (not limited to official advisory services engagements) in the respective areas.

Figure 3.4. Increase in Lending by Segment and International Finance Corporation Engagement (Three out of Four Banks), 2014–22

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: IFC = International Finance Corporation; SME = small and medium enterprise.

Assessing IFC’s impact in the agribusiness sector is also hindered by lack of monitoring. The impacts of IFC support on agribusiness are difficult to assess because of the lack of relevant data monitoring. Clients suggest that IFC support enabled them to expand production and distribution, upgrade environmental standards, improve energy efficiency, identify and better manage risks, and improve monitoring systems and environmental standards. However, similar to in the financial sector, data to assess IFC’s overall impact on development outcomes—and also triangulate information gathered through interviews—are limited. IFC tracks some standard indicators—for example, suppliers and buyers reached, volume of product, employment, and score (out of 100 percent) on environmental and social management—but does not report on achievements for a client’s specific project. For instance, it does not track the extent to which IFC-supported capacity expansions enabled production to increase, does not track export volumes and values, and for projects that aimed to support access to food by poor people through distribution networks, did not monitor the poverty profile of the areas reached through the distribution networks. Such aspects may be examined ex post in XPSRs,10 but few XPSRs were done for projects active in Ecuador during the evaluation period. The lack of focus of IFC monitoring on outcomes attributable to IFC support limit the ability to identify IFC’s contribution to development outcomes, its accountability for development outcomes, and its ability to course correct when outcomes fail to be attained.

- The International Monetary Fund would not conduct an Article IV consultation in Ecuador until 2014 (with the first on-site Article IV occurring the following year).

- Based on interviews with World Bank country office staff and management.

- The Global Trade Finance Program (GTFP) offers confirming (international) banks partial or full guarantees to cover payment risk on banks in the emerging markets (see https://www.ifc.org/en/what-we-do/sector-expertise/financial-institutions/global-trade/global-trade-finance for more information). GTFP remained relevant throughout the evaluation period, with $478 million of use through fiscal year 2022.

- In the wake of increasing country risk, the International Finance Corporation would close the trade lines in 2010 and reopen them in 2013.

- Based on interviews with the International Monetary Fund and World Bank staff and program documentation.

- For example, the first development policy operation required the elimination of subsidies on premium gasoline, industrial diesel, and natural gas for commercial and industrial use—all of which were regressive, with most consumption by higher-income quintiles.

- On the basis of interviews with the World Bank development policy operation team, with little notice, the president announced the broader energy subsidy reforms in place of the original plans to implement a value-added tax.

- GTFP offers confirming (international) banks partial or full guarantees to cover payment risk on banks in the emerging markets (see https://www.ifc.org/en/what-we-do/sector-expertise/financial-institutions/global-trade/global-trade-finance for more information). GTFP remained relevant throughout the evaluation period, with $450 million of use through fiscal year 2022.

- The Independent Evaluation Group was unable to develop a consistent time series data set for International Finance Corporation clients’ lending to small and medium enterprises, women-owned small and medium enterprises, and for climate, and relied on data provided by each bank. One bank declined to provide data. For projects that supported climate finance, only one out of five projects monitored the volume of climate lending, and this project reports data for only one year. Another project monitored estimated greenhouse gas reductions, reporting on it for only two years.

- Expanded Project Supervision Reports, which the International Finance Corporation prepares for 40 percent of its projects and the Independent Evaluation Group validates.