The World Bank Group in Ecuador

Chapter 2 | Rebuilding a Productive Partnership with the Government of Ecuador

Highlights

The World Bank’s relationship with the government of Ecuador was severely affected by a series of events early in Rafael Correa’s presidency, including the cancellation of World Bank loans, the expulsion of the World Bank’s country representative, and a selective debt default by the government of Ecuador.

The World Bank gradually rebuilt its dialogue with the government by delivering low-visibility analytic work and technical assistance in politically nonsensitive sectors. The World Bank increased its finance for analytic activities sixfold to increase its nonlending technical assistance.

The World Bank’s dialogue with municipal authorities paved the way for the World Bank’s operational reengagement in Ecuador.

The World Bank’s reengagement approach was relevant for partnership rebuilding but occasionally came at the expense of project quality. The speed of infrastructure project preparation to meet government demands came at the expense of quality engineering designs, which resulted in significant implementation delays across projects.

World Bank strategies from 2007 to 2017 neglected to include results frameworks with higher-level outcome objectives, reducing accountability and blurring the line of sight between World Bank Group support and higher-level achievements.

Partnership rebuilding was slowed by lack of a clear approach to working with the government of Ecuador. The World Bank would take six years to approve a formal strategy for working with the government, and lack of internal guidance on the strategy hampered the World Bank from taking consistent actions.

The World Bank’s eventual strategy was aligned with the government’s national plan and priorities identified in earlier diagnostic work. Operational support to municipal capacity building was relevant both to improved public service delivery and to the context of evolving responsibilities at the local level.

The World Bank underestimated the government’s institutional capacity weaknesses, leading to project implementation delays.

The Bank Group failed to mitigate implementation risks at the strategy phase and over the project cycle by including covenants in additional financing approvals or leveraging the International Finance Corporation to play a larger role in guiding municipal authorities on public-private partnerships.

Introduction

This chapter examines the steps taken by the World Bank to restore a productive engagement with the government of Ecuador after a structural break in 2007. After discussing the early events that defined the structural break, the chapter reconstructs the evolving theories of change that guided the World Bank’s major decisions toward reengagement through the end of the operational normalization period. The chapter then assesses the relevance and effectiveness of the World Bank’s reengagement strategy and demonstrates that the World Bank was largely effective in rebuilding a partnership with the government through low-visibility technical assistance that opened spaces for dialogue. However, the World Bank’s desire to respond quickly to government needs came at the expense of project design and monitoring quality, which undermined the World Bank’s development impact and accountability for achieving development outcomes.

The relevance and effectiveness of the World Bank’s reengagement strategy are based on two distinct (but related) objectives. The first objective relates to achieving specific development outcomes within the country, attributable to the partnership activities. In general, the Bank Group articulates the development outcome objectives it aims to support within the pertinent CPFs governing the engagement cycles, with the plans for achieving these objectives outlined through a planned portfolio of activities. The second objective concerns the partnership status. This objective encompasses the set of conditions necessary for an effective country partnership to be established—one in which the resources of both the World Bank and the government are optimized to deliver development solutions. A minimum level of partnership is necessary to provide any support for the country’s development objectives. In this sense, the partnership-rebuilding aspect of the reengagement is a necessary (but insufficient) condition for the attainment of development outcomes.

The chapter considers both aspects of the World Bank’s reengagement strategy. Relevance to partnership building considers the degree to which the strategy and its associated activities would be expected to contribute to the restoration of a productive partnership with the government of Ecuador, and relevance to development challenges considers the degree to which the support delivered under the engagement aligned with key national development priorities and was sensitive to the political economy and capacity conditions of the government. Effectiveness of partnership rebuilding takes into consideration the degree to which the reengagement strategy and its associated activities resulted in a more productive partnership with the government, and effectiveness of development solutions considers the development outcomes achieved that are attributable to the Bank Group’s support. In evaluating the effectiveness of the reengagement with respect to partnership building, the team considered the extent to which the actions created opportunities for dialogue, built trust with the government, and demonstrated mutual benefit.

The chapter focuses on the World Bank’s strategies over the limited activity and the operational normalization periods from 2007 to 2017. The time frame reflects the period over which the World Bank’s relationship was fundamentally altered and when relationship rebuilding occurred. The chapter focuses on World Bank because IFC’s investment program was largely unaffected by the events of 2007.

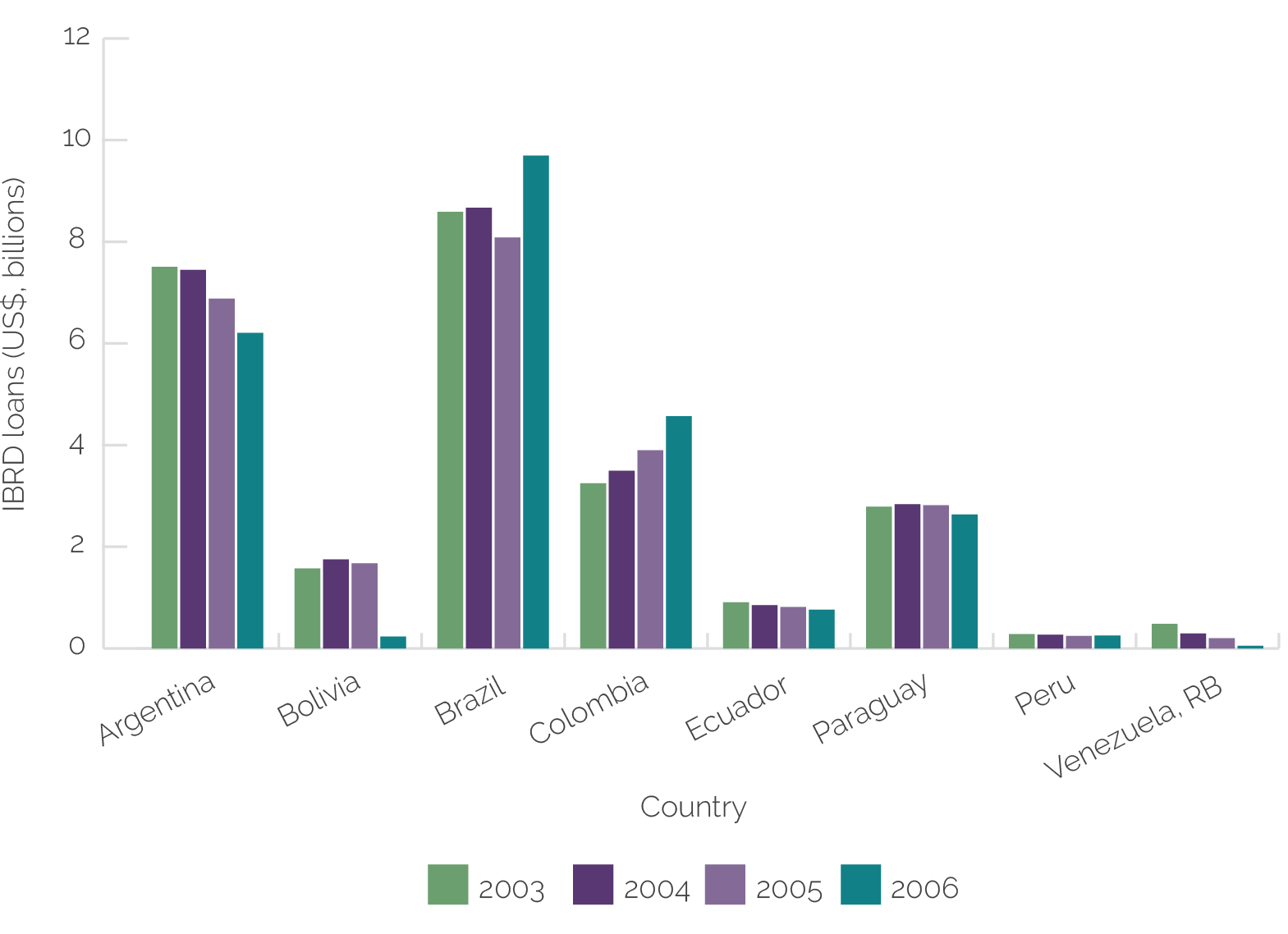

Background on the Break in the World Bank’s Engagement in Ecuador

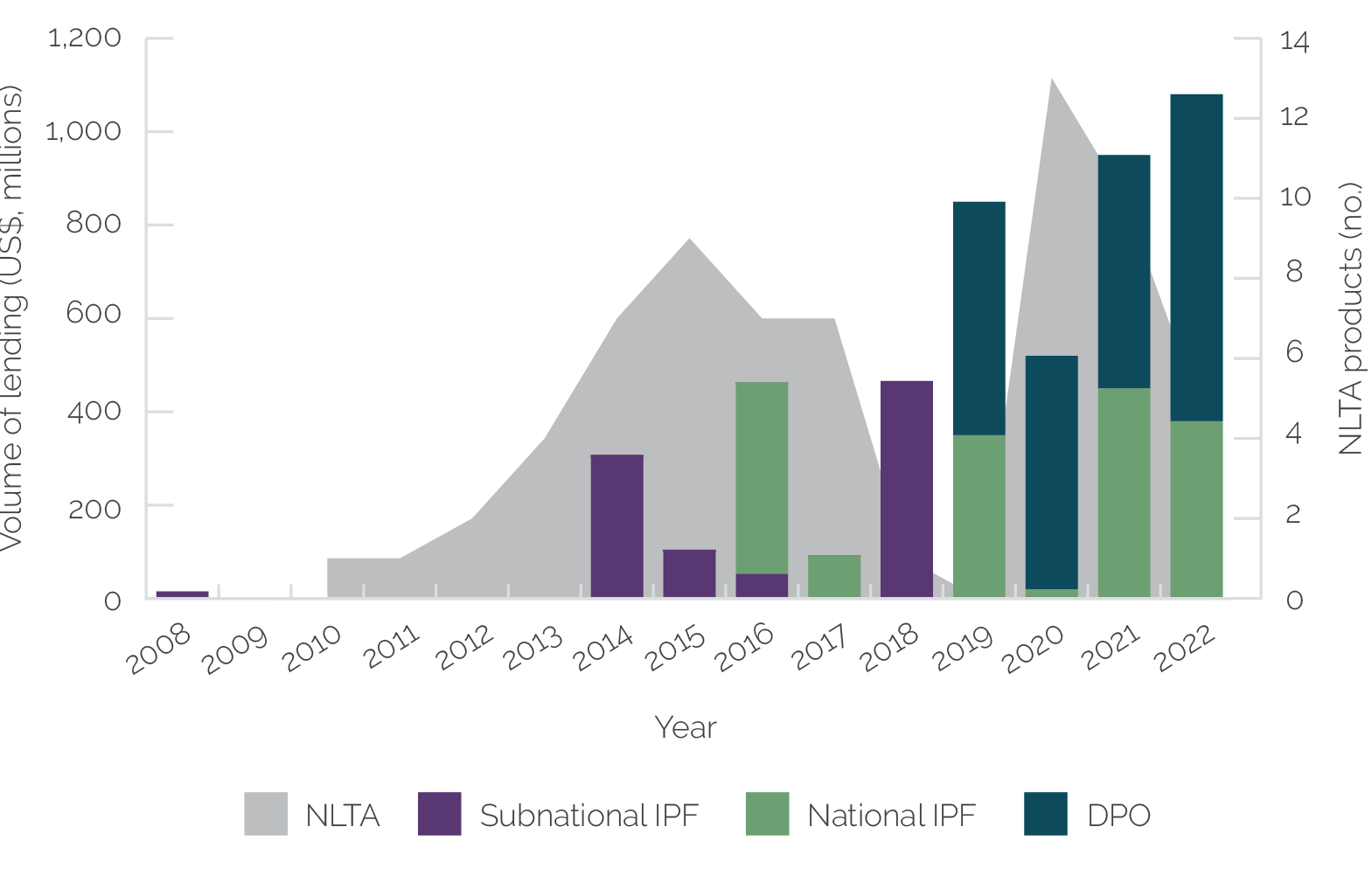

The Bank Group had an established program of World Bank and IFC activities in Ecuador in the early 2000s. Between 2003 and 2006, the World Bank’s lending portfolio in Ecuador amounted to about $800 million, small relative to Latin American comparators but relatively large in per capita terms (figure 2.1).1 Development policy financing accounted for a little more than one-third of all World Bank financing over the period. The World Bank’s support over the Country Assistance Strategy 2003–07 cycle focused on helping the government of Ecuador weather the economic fallout from the 1999 fiscal crisis, including support for macroeconomic stabilization through building fiscal buffers, complemented by improving inclusive access to economic resources and strengthened governance and public service delivery. For its part, IFC had established trade finance with three banks, supporting export-oriented businesses to expand. IFC was also supporting two agribusiness companies to expand their operations and advising on simplification of regulatory requirements in two municipalities.

Figure 2.1. Size of the Ecuador International Bank for Reconstruction and Development Loan Portfolio, Early 2000s

Source: International Debt Statistics, World Bank.

Note: IBRD = International Bank for Reconstruction and Development; RB = República Bolivariana.

The World Bank’s cancellation of a 2005 loan contributed to a fracturing of the relationship between the World Bank and the government of Ecuador. The World Bank had approved a $100 million Second Fiscal Consolidation and Competitive Growth structural adjustment loan to Ecuador in March 2005, after the government of Ecuador had met all the effectiveness conditions, including a condition to legislate that 70 percent of windfall oil revenues would be used to pay off external public debt. When significant antigovernment protests began in reaction to the austerity measures in connection with that loan and conditions of an IMF program, President Lucio Gutiérrez was removed by Congress in April 2005. Rafael Correa, the new minister of finance, successfully lobbied Congress to reduce the required allocation from the oil stabilization fund for external debt repayment and increase spending on health and education. The World Bank responded by canceling the Second Fiscal Consolidation and Competitive Growth loan to Ecuador, leading to Correa’s resignation in August 2005. He would subsequently launch a successful run for president in 2006 and assume office in January 2007.

Three actions early in the Correa presidency disrupted the partnership between the World Bank and the government of Ecuador. These events would set the stage for a heavily circumscribed dialogue between the World Bank and the government of Ecuador from 2007 to about 2013. The events were as follows: (i) the dismantling of ongoing Bank Group operations, (ii) the expulsion of the World Bank’s country representative, and (iii) a selective debt default exercise.

- First, the government of Ecuador withdrew from World Bank borrowing. Starting in 2007, the government discontinued further borrowing from the World Bank. Projects under preparation were canceled, and active projects were closed before full disbursement, with the government failing to meet subsequent effectiveness conditions. For example, the implementation partner for a $45 million World Bank–supported project on rural development for Indigenous and Afro-Ecuadoran peoples halted steps to advance the project shortly after the change in administration (World Bank 2006b).2 The $76 million National Rural Water Supply and Sanitation Project (of which the World Bank was to finance $48 million) that was declared effective in December 2006 was closed with only $7.5 million of World Bank financing disbursed. The $32 million Rural Roads Project (of which the World Bank was to finance $20 million) was approved in July 2006 but never became effective. In total, 15 operations underway (either active or under preparation) were subsequently canceled or closed early.3

- Second, the government of Ecuador expelled the World Bank’s country representative in Ecuador. Shortly after taking office, the president declared the World Bank’s country representative persona non grata and requested the representative leave the country (Weitzman 2007). The expulsion was one of only two dismissals of World Bank representatives by country authorities.4

- Third, the government of Ecuador defaulted on a large portion of its foreign debt. In July 2007, the government formed the Comisión para la Auditoría Integral del Crédito Público (Comprehensive Public Credit Audit Commission) to evaluate the legality of national debt incurred by the country over the prior three decades, including loans from multilateral development banks. The result of that inquiry was the default on two corporate bond issues totaling $3.2 billion in December 2008 (about one-third of Ecuador’s external debt), subsequently repurchased by the government at a discount at the end of 2009.5

The combined effect of these developments was a steep decline in interaction between the government of Ecuador and the World Bank. The dialogue between the World Bank and the government was circumscribed for several years, and the World Bank would not initiate new lending in Ecuador until 2013.

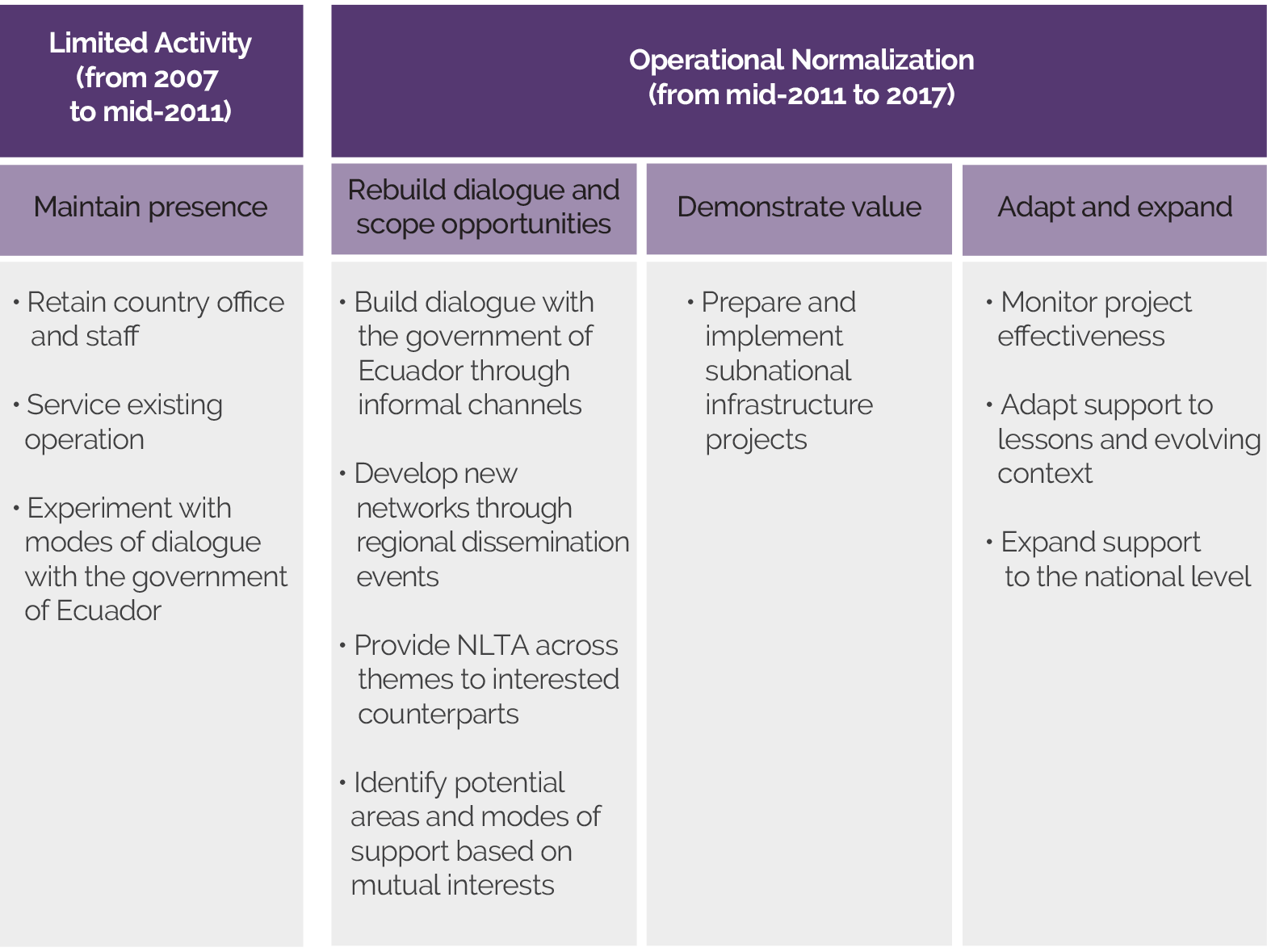

World Bank Actions toward Reengagement over 2007–17

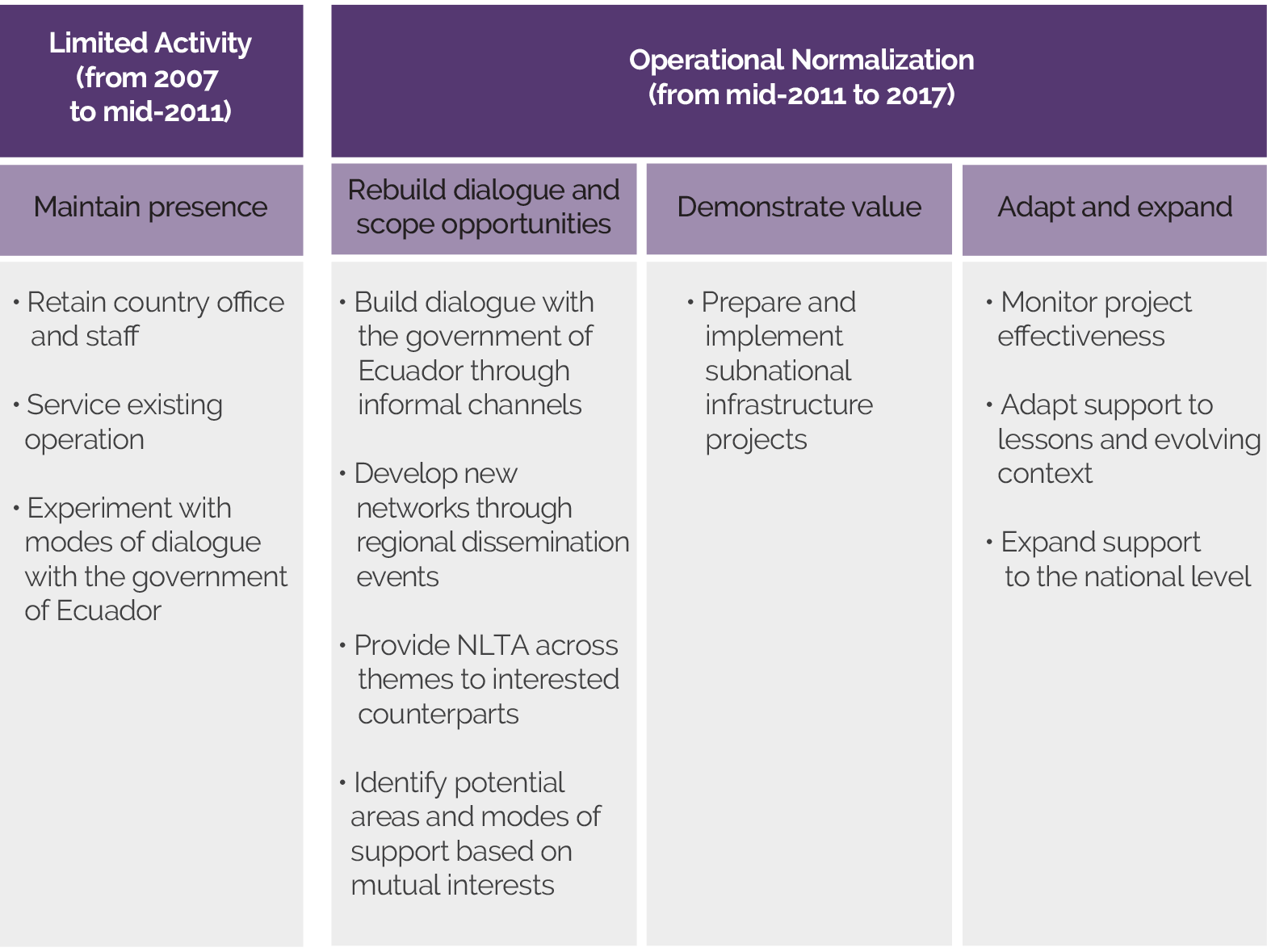

The World Bank’s actions from 2007 to 2017 reflected expanding engagement objectives as the partnership with the government of Ecuador strengthened. Although the World Bank did not articulate a formal strategy for reengagement until the spring of 2013, it is possible to reconstruct the evolving theories of change that guided World Bank decisions over the 2007–17 period.6 The objectives can be broadly described as follows: stage 1—maintaining a presence; stage 2—rebuilding dialogue and scoping opportunities; stage 3—demonstrating value, through subnational operations; and stage 4—adapting and expanding (figure 2.2).

Figure 2.2. Key Stages in World Bank Reengagement Decisions

Source: Independent Evaluation Group classification based on World Bank country program review.

Note: NLTA = nonlending technical assistance.

Stage 1: Maintaining Country Presence as a Window for Dialogue

The World Bank’s main objectives from 2007 to mid-2011 were to preserve its presence in Ecuador and prevent a more permanent disengagement, with a view to eventually supporting the government development agenda in some capacity. In the midst of a rapidly devolving partnership, World Bank management took no explicit steps to address the ruptured partnership with the government of Ecuador.7 However, the World Bank maintained its country office in Quito with a view to eventually reestablishing dialogue with the government—a move that contrasted a contemporaneous decision by Latin America and the Caribbean management to close the World Bank’s country office in Caracas.8 With a single operation financed by the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, still active in Ecuador at the time, and with no formal request for the World Bank to close its office, the World Bank’s country management successfully argued to maintain a small country office in Quito, from which it could assess developments and gradually rebuild dialogue with the government of Ecuador.

The World Bank maintained a few existing channels of dialogue with the government. The World Bank’s dialogue with the Coordinating Ministry for Social Development (MCDS), to whom it had delivered a 2006 child nutrition review, remained intact after the structural break, and the World Bank leveraged that dialogue to initiate a nonlending technical assistance (NLTA) activity in July 2008 to explore how the government conditional cash transfer program—BDH—could be used to incentivize nutritional outcomes (with a follow-up activity in 2010).9 The World Bank also responded to a request from the Coordinating Ministry for Production, Employment, and Competitiveness (MCPEC) for NLTA on select subjects related to productivity in 2011.10 Operationally, the World Bank serviced the single World Bank–financed project under implementation (in Chimborazo).11 It also drew on a global trust fund to finance a small technical assistance project on disaster prevention and management for the Municipality of Quito.12

Stage 2: Scoping Potential Partnerships

Over FY12 and FY13, the World Bank took greater steps to proactively rebuild dialogue with the government of Ecuador and scope potential partnerships. Beginning in mid-2011, as the debt default exercise was resolved, the World Bank shifted from a holding pattern to actively seeking to reestablish dialogue with a few line ministries and establish new partnerships with subnational authorities.

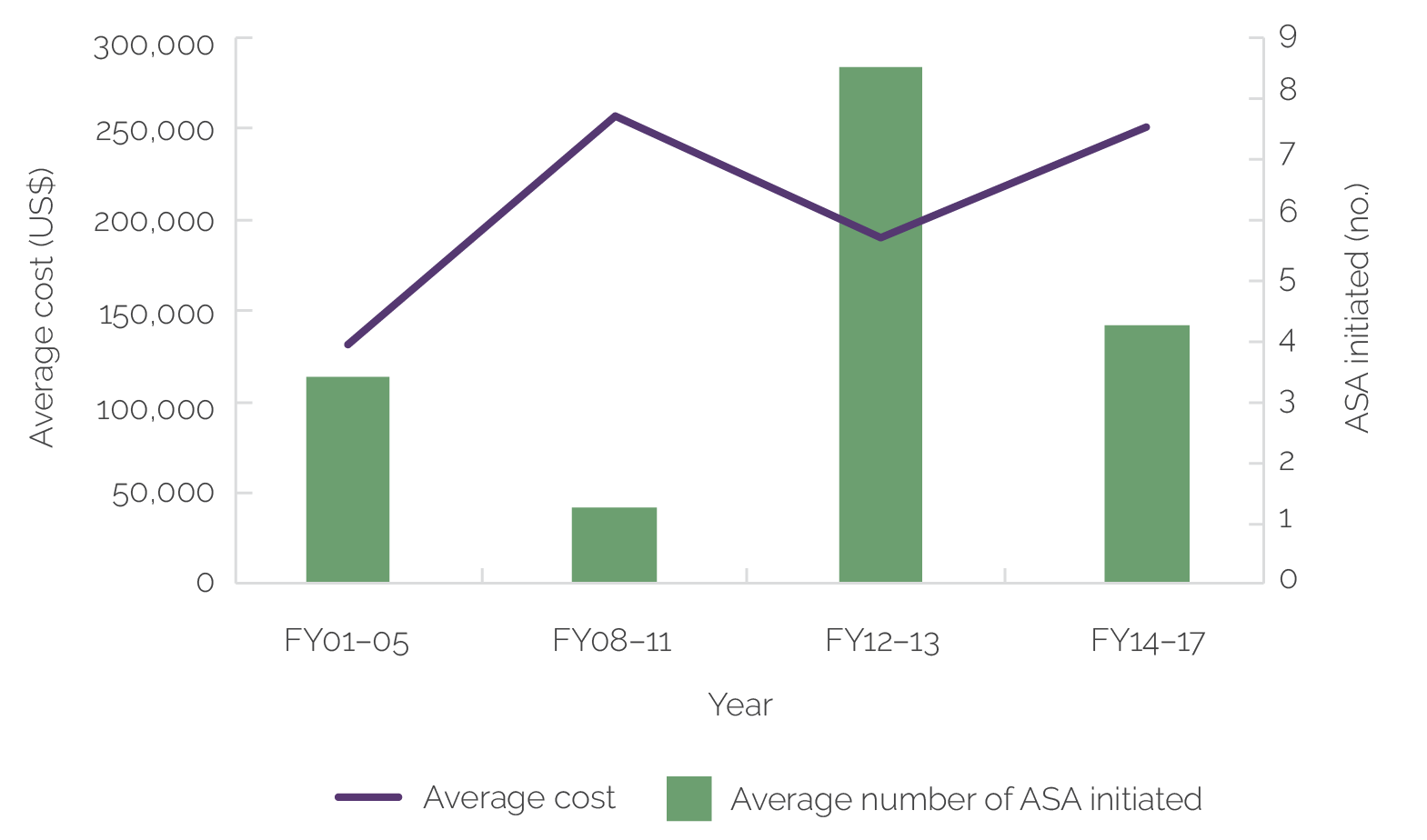

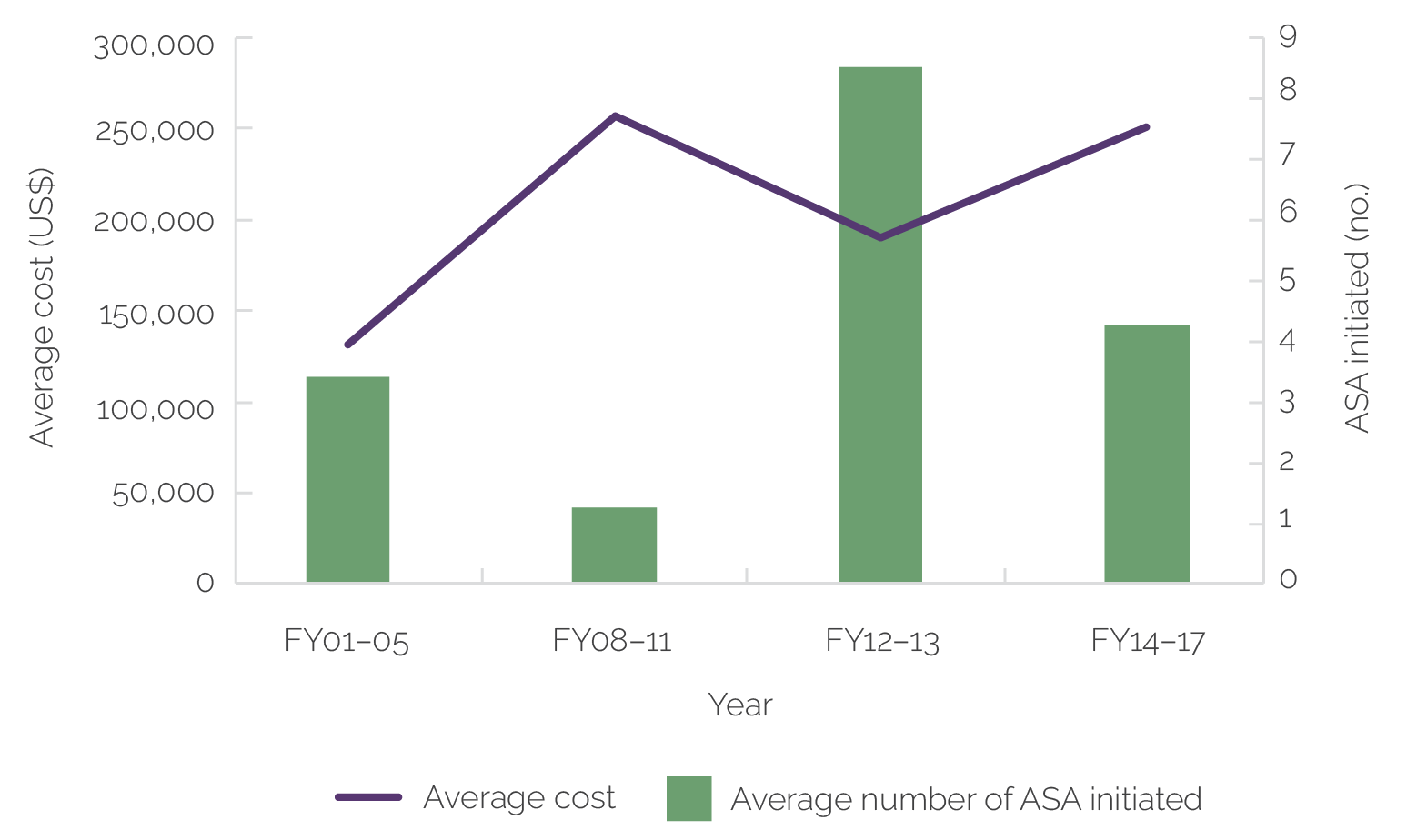

The World Bank built dialogue with the government of Ecuador through NLTA. The World Bank initiated 17 pieces of analytic work over FY12–13, a ninefold increase in the number of ASA per year from the previous four years (figure 2.3). The World Bank provided NLTA across diverse topics, including state-owned enterprise governance, informality, innovation, environmental management, payment systems, and low-income housing finance. The World Bank also initiated NLTA in a few sectors that would ultimately expand over the period, including nutrition and social protection, transport, and disaster risk management (DRM).

Figure 2.3. Advisory Services and Analytics Initiated per Year in Ecuador: Reengagement, Fiscal Years 2008–17 versus Fiscal Years 2001–05

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: ASA = advisory services and analytics; FY = fiscal year.

The World Bank financed the NLTA scale-up through a sixfold increase in budget (and increased use of trust funds). Over the period FY12–13, the World Bank increased its budgeting to ASA by more than 600 percent, whereas its use of trust funds for financing ASA increased tenfold. The World Bank drew on trust funds to partially finance NLTA activities on nutrition, social protection, DRM, and affordable housing. With the significant scale-up in finance, the number of ASA increased from 2 activities over the FY08–10 period to 21 over the FY11–13 period.

The World Bank used NLTA to rebuild lost knowledge. On several occasions, the World Bank took narrow openings and expanded the dialogue beyond the original requests. For example, when MCPEC requested the World Bank’s help in improving design of two of its flagship innovation programs in 2011, the World Bank broadened the assistance to conduct critical economic analysis of Ecuador’s enterprise sector, allowing the World Bank to strategically reposition itself on private sector development issues after a five-year hiatus. The World Bank similarly expanded NLTA on labor informality to build knowledge on minimum wage legislation.

The World Bank was resourceful in creating channels for dialogue with the government of Ecuador. Country directors for Ecuador over the 2007–12 period indicated that personal relationships were instrumental in creating the inroads for productive dialogue.13 For several years after the break, formal World Bank meetings with line ministries were difficult to secure. Building up the small set of government counterparts receptive to World Bank support often depended on taking advantage of existing personal relationships (for example, drawing on mutual connections of World Bank staff and line ministries to enable introductions) or through meetings at informal social events. The World Bank also strategically used existing regional or global reports as a vehicle for dialogue with government officials, in which it could demonstrate value and also highlight Ecuador’s successes. In 2012, for example, the World Bank hosted one of the launch events for the World Report on Disability in Quito (WHO and World Bank 2011), in which it highlighted actions Ecuador had taken to enhance disability access and rights and build dialogue with the vice presidency.14 Similarly, in 2012, the World Bank organized a workshop on safe and inclusive cities, “Hacia Ciudades Seguras, Sostenibles e Incluyentes,” and co-sponsored the event América Solidaria with the office of the vice president of Ecuador to spotlight successful interventions taken by the government of Ecuador in DRM, transport, and housing.

Several streams of World Bank dialogue gained traction with the government of Ecuador and expanded. The World Bank’s dialogue on improving child nutrition through BDH led to a program of NLTA to support broader aspects of social protection, including improvement of skills and employability of BDH recipients, the need for unemployment insurance reform, and improvement of the social and economic inclusion of people with disabilities. At the subnational level, the World Bank capitalized on the trust fund–financed technical assistance project on disaster prevention and management for the Municipality of Quito to broach discussions on DRM with other municipalities, leading to follow-up NLTA covering other cities. The World Bank leveraged the municipal dialogue on DRM to discuss other topics, including water and waste management.15 Separately, the World Bank initiated an NLTA program on transport to provide technical support to municipal governments planning urban transport upgrades.16 The NLTA focused on mobility planning, design, policy, and financing.

The World Bank’s municipal transport NLTA helped open the door to an operational reengagement in Ecuador. The World Bank’s NLTA to subnational governments on urban transport revealed a demand for World Bank financial support at the subnational level. Most prominently, the Municipality of Quito required considerable financing for its underground metro construction. Although the city had secured commitments from IDB, CAF, and the European Investment Bank, it additionally wanted the World Bank as a partner, primarily for cofinancing but also because of the World Bank’s experience in transport system construction. In addition, the city of Manta was planning road network upgrades together with improvements to the water and sanitation network and nonmotorized transport infrastructure. With the objective of reestablishing an operational relationship in Ecuador, the World Bank took steps to repair the relationship with the president through high-level talks (actions that had not been taken previously). The culmination of stage 2 was the identification of two municipal transport projects that would reinitiate the World Bank’s operational presence in Ecuador.

Stage 3: Demonstrating Value through Subnational Operations

The World Bank demonstrated its value and changed government perceptions of it through subnational investment projects. Interviews with country management over the operational reengagement suggest that the World Bank focused its operational reengagement on subnational infrastructure investment projects as the best platform for demonstrating value and changing perceptions within Ecuador. First, the World Bank felt that its deep experience with infrastructure investment projects would allow the World Bank to best demonstrate its operational effectiveness, technical rigor, and value for money after the seven-year lapse in operations. Second, targeting municipal governments, which had their own political autonomy, allowed the World Bank to circumvent the impasse in dialogue that continued at the national level.

The World Bank prepared two municipal-level infrastructure projects—the first World Bank–financed operations in Ecuador since 2007. The FY14 $205 million Quito Metro project (with additional $230 million financing in June 2018) sought to improve urban mobility through construction and operationalization of a metro line in the city of Quito, including investments in underground stations, tunnel and track, train cars, and technical assistance. The Quito Metro project was jointly financed by the World Bank, IDB, CAF, and the European Investment Bank. The FY14 $100 million Manta Public Services Improvement Project sought to strengthen the sustainability of the municipality’s water, sanitation, and urban mobility services through investments in water supply and sewerage, road improvement, and institutional strengthening. Both projects provided finance directly to municipal authorities, with the central government providing a guarantee. The World Bank would also begin preparation of the Guayaquil Wastewater Management Project, aimed at increasing access to improved sanitation services and reducing wastewater pollution in Ecuador’s second largest city, which would be approved the following year.

The World Bank’s reengagement strategy was formalized in its ISN for FY14–15. Approval of World Bank projects in Ecuador required a formal country strategy. In the spring of 2013, the Bank Group’s ISN was approved by the Board, laying out a flexible strategy of support around three broad pillars—sustainable and inclusive growth, social protection and quality service provision, and public sector institutional strengthening. Its focus was partnership rebuilding, with the main objective to “consolidate progress in the dialogue in a few key areas and have flexibility to respond to evolving requests for support” (World Bank 2013).

Stage 4: Adapting and Expanding

The World Bank’s strategy after FY15 remained flexible to the evolving context and government dialogue. The World Bank followed up the ISN with another short-term strategy, the CEN for FY16–17, with two broad pillars of support designed to be flexible to its evolving engagement by capturing a range of potential activities. The first pillar—quality service delivery (including safety nets, water and sanitation, and transport)—umbrellaed the operation under preparation in Guayaquil and an urban mobility project planned in Ibarra, as well as continued support toward social protection. The second pillar—promoting economic diversification—would encompass a range of technical assistance that had already been started on competitiveness, innovation, and productivity. A cross-cutting theme of mitigating the risks from climate change was also included, which could incorporate ongoing technical dialogue on DRM (which would ultimately lead to a project at the national government level on risk mitigation and emergency recovery from both natural disasters and macroeconomic shocks).17

The World Bank’s strategic shift to national-level projects was in part to manage portfolio risks. The CEN shifted the operational focus to the national level as the World Bank’s subnational portfolio exhibited increasing implementation challenges. At the time of its drafting, all three World Bank projects approved over the ISN cycle (the Quito Metro project, the Manta Public Services Improvement Project, and the Guayaquil Wastewater Management Project) were exhibiting implementation delays, in part attributed to their lack of familiarity with World Bank processes and procedures. The World Bank’s shift to central government lending reflected an effort to mitigate further risks to the portfolio. Interviews with country management suggest that the shift out of municipal infrastructure was part of an adjustment to manage expectations about the reengagement. With few results to show at the time of the CEN, in 2016, the World Bank shifted its reengagement approach to lending at the national level, where institutional capacity for implementation was greater.

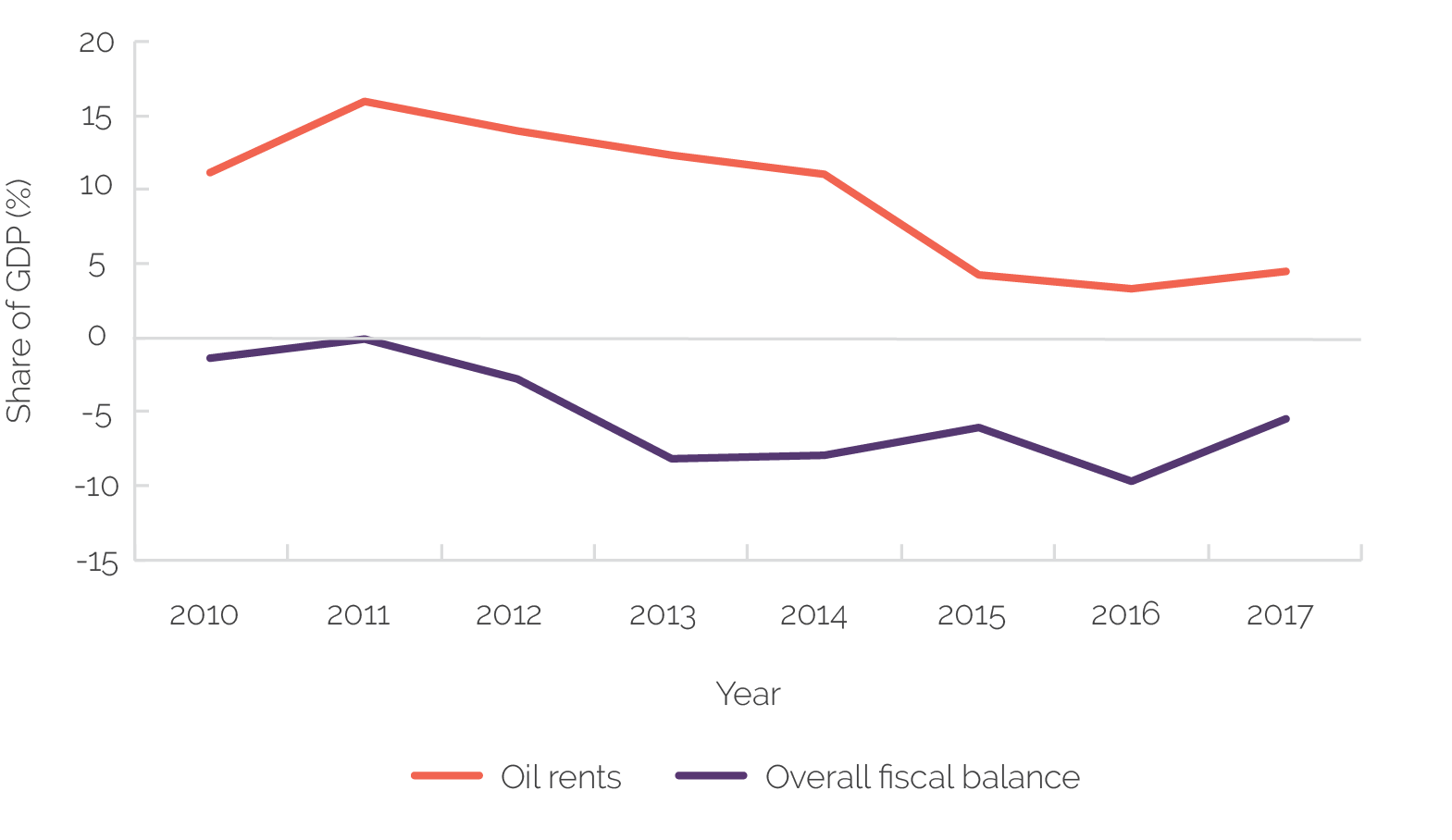

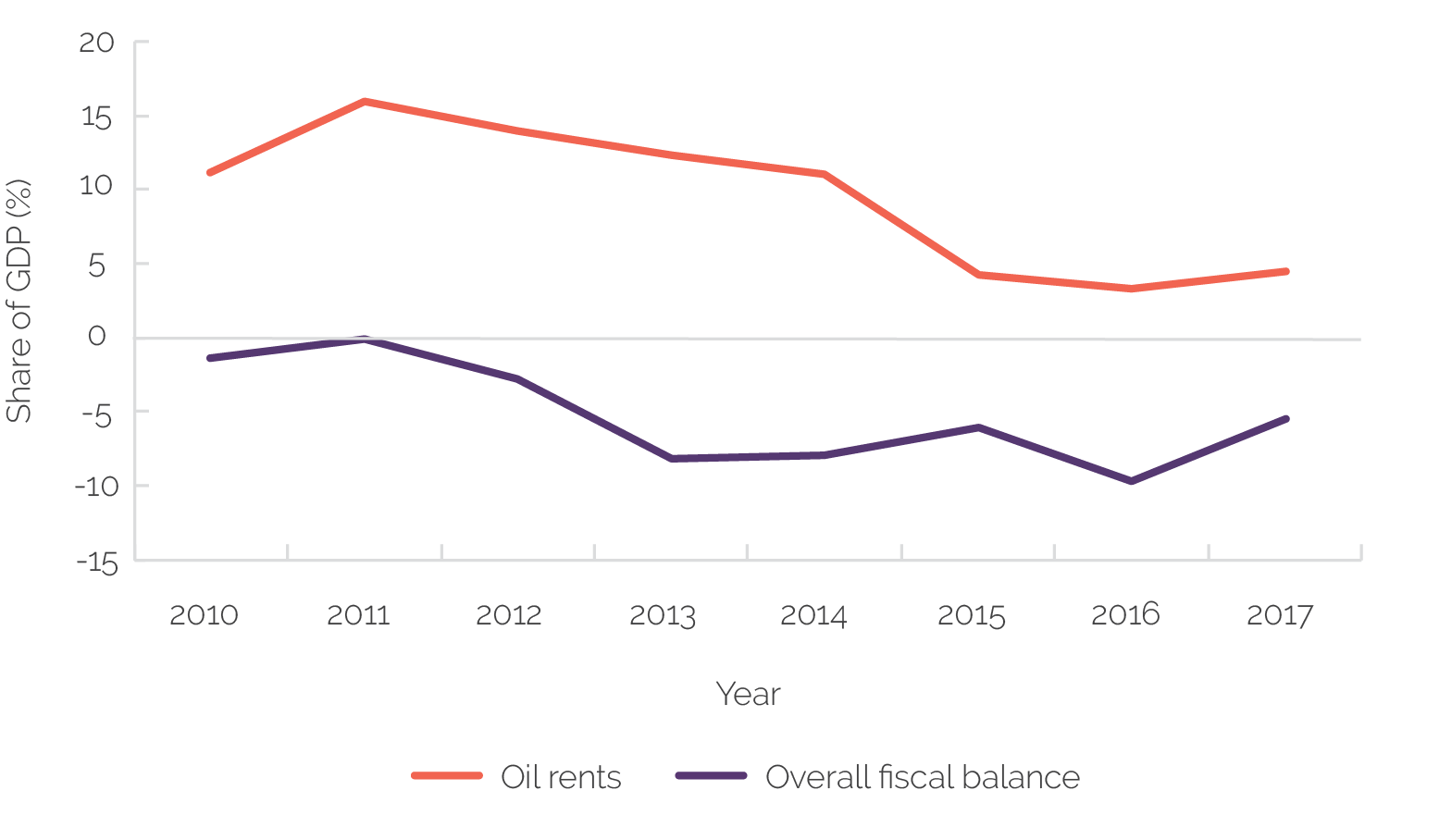

The World Bank’s shift to national-level operations also reflected the central government’s renewed openness to World Bank finance. The macroeconomic environment in Ecuador had changed substantially from the ISN period, which created central government demand for World Bank finance after a break of eight years. Crude oil prices had dropped more than 50 percent between 2011 and 2015, and Ecuador’s crude oil rents over the same period dropped from 15.6 percent of GDP to 4.4 percent (World Bank 2024b; figure 2.4). In an environment of reduced fiscal space, the central government reopened channels for World Bank borrowing.

Figure 2.4. Overall Fiscal Balance and Oil Rents, 2010–17

Sources: Macro Poverty Outlook (database), World Bank; World Bank 2024b.

The World Bank would deliver four national-level projects over the CEN cycle. These included a DRM project (FY16 Ecuador Risk Mitigation and Emergency Recovery Project), two investment projects in education (FY16 Supporting Education Reform in Targeted Circuits and FY17 Transformation of the Tertiary Technical and Technological Institutes Project), and an agriculture project (Sustainable Family Farming Modernization Project).

The World Bank also planned to ramp up its analytic work to inform a new government administration. In anticipation of a new government in mid-2017,18 the CEN made plans for a significant increase in analytic work. The CEN proposed an ASA program that would build knowledge on macro and structural policy issues, which could underpin the World Bank’s medium-term assistance. Toward that purpose, the World Bank prepared a Country Economic Memorandum in FY16, which would assess challenges facing the oil and gas sector, export diversification, the investment climate and innovation, and human capital development. The Country Economic Memorandum would be the first piece of major analytic work since 2007 to candidly outline major constraints of the development model, including those related to the size of the public sector; a poorly targeted fuel subsidy system; labor market rigidities and an opaque and complex formula for determining minimum wage increases; uncertainty regarding the regulatory environment; and the lack of resolution of international investor disputes. The World Bank would also develop a set of policy notes across a range of themes, including fiscal policy, financial sector stability and regulation, and social protection.

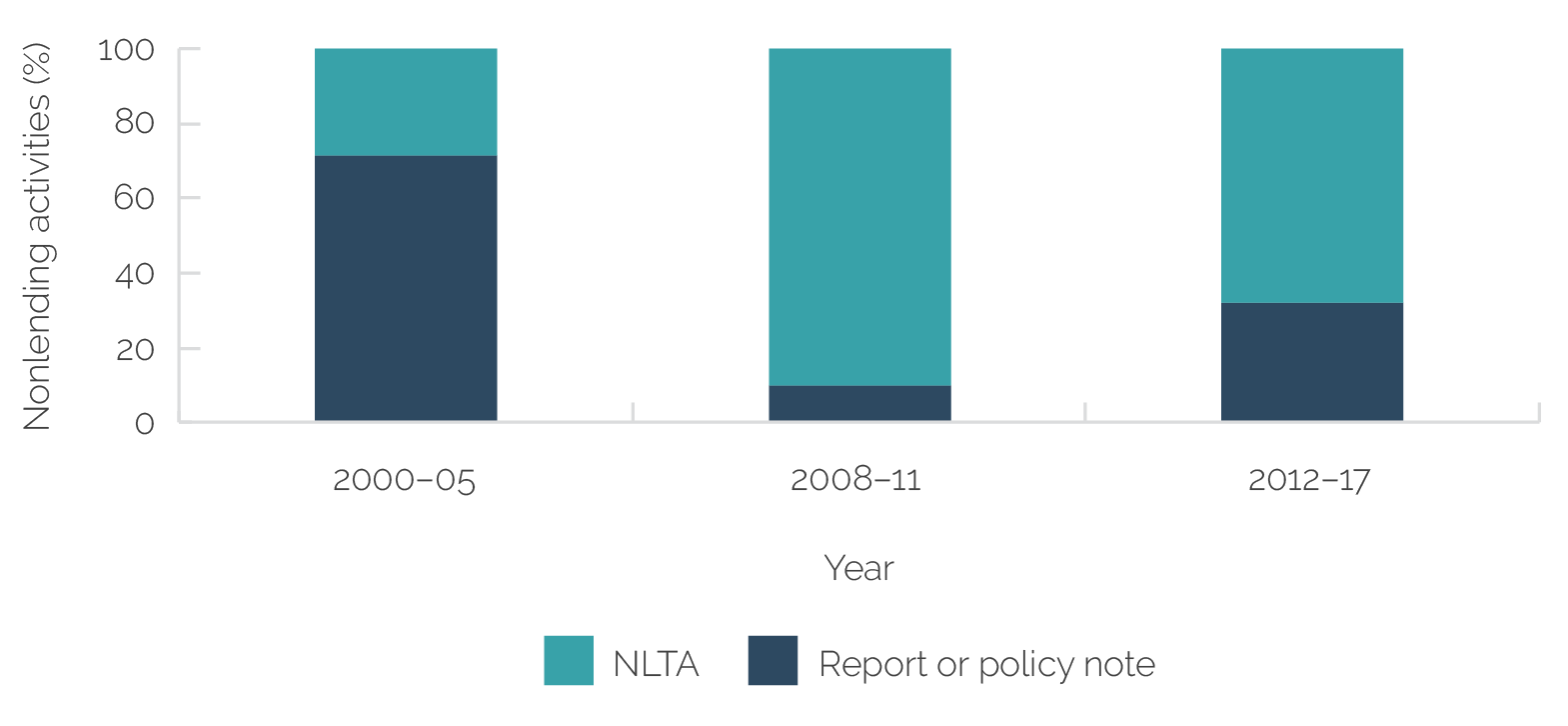

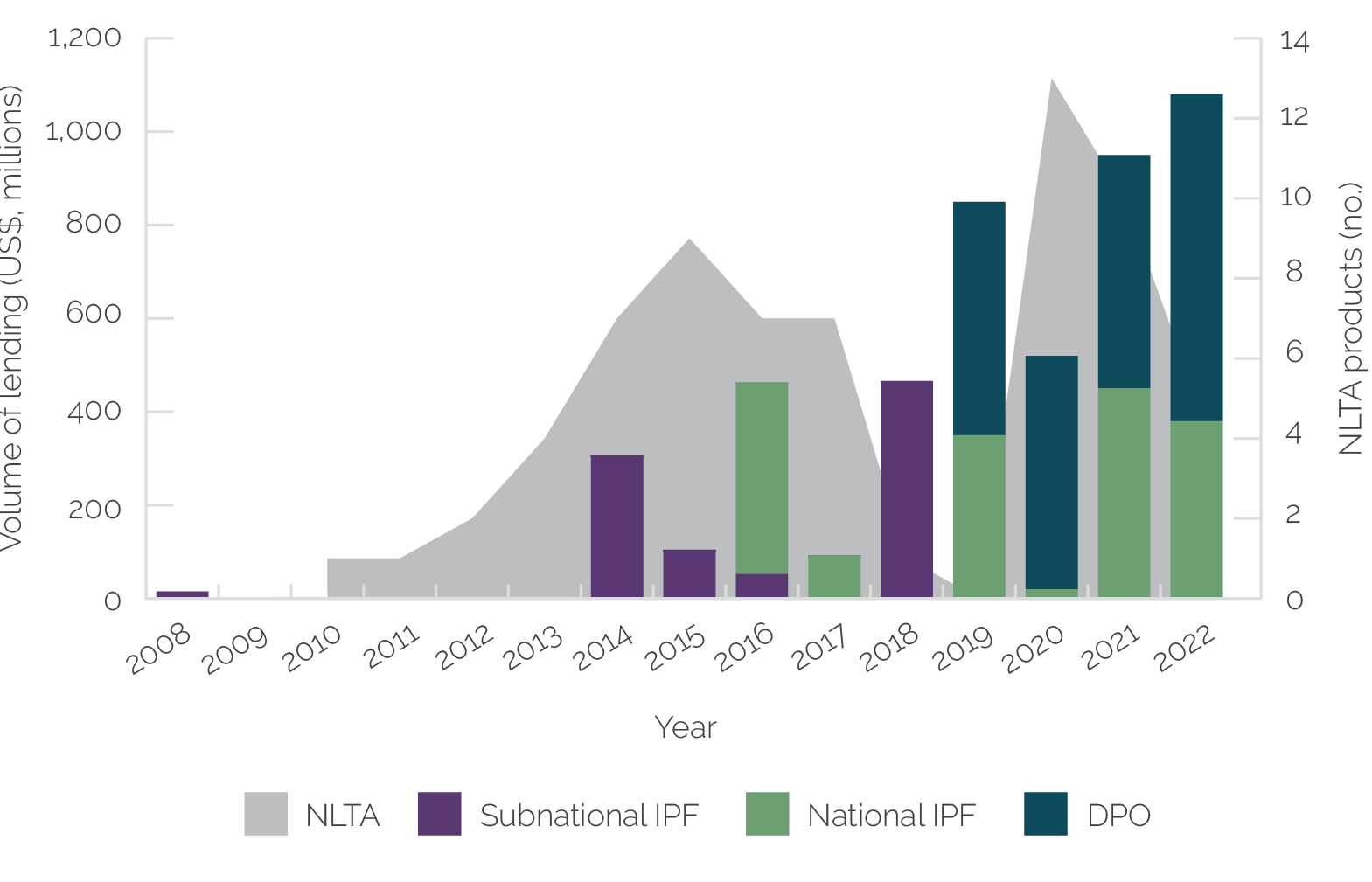

The World Bank’s operational support from FY14 to FY17 was limited to investment finance. Despite the strengthened partnership, the World Bank would not provide policy-based lending to Ecuador until a new government was installed after May 2017. Only then, in support of the government’s new development model, would the World Bank provide policy-based lending to Ecuador (in 2019, for the first time since 2006). That shift reflected the full rebuilding of the relationship between the World Bank and the government of Ecuador, from strictly NLTA to subnational-level IPFs, to national-level IPFs, to national-level DPOs (figure 2.5).

Figure 2.5. Evolution of World Bank Lending to Ecuador by Level of Government and Instrument, 2008–22

Source: Independent Evaluation Group staff calculations from World Bank operational portfolio data.

Note: The 2018 lending reflects additional financing for earlier subnational projects. DPO = development policy operation; IPF = investment project financing; NLTA = nonlending technical assistance.

Assessing the Relevance and Effectiveness of the World Bank’s Reengagement Strategy

Relevance and Effectiveness to Partnership Rebuilding

The World Bank was effective in rebuilding its partnership with the government, but the strategy limited the World Bank’s accountability for delivering outcomes. Many of the steps taken by the World Bank were effective in creating greater opportunities for dialogue, building goodwill, and demonstrating the World Bank’s value. However, the World Bank’s formal strategies over the period prioritized flexibility over results, limiting World Bank accountability and monitoring. The World Bank’s desire to demonstrate value through quick project preparation came at the expense of project quality.

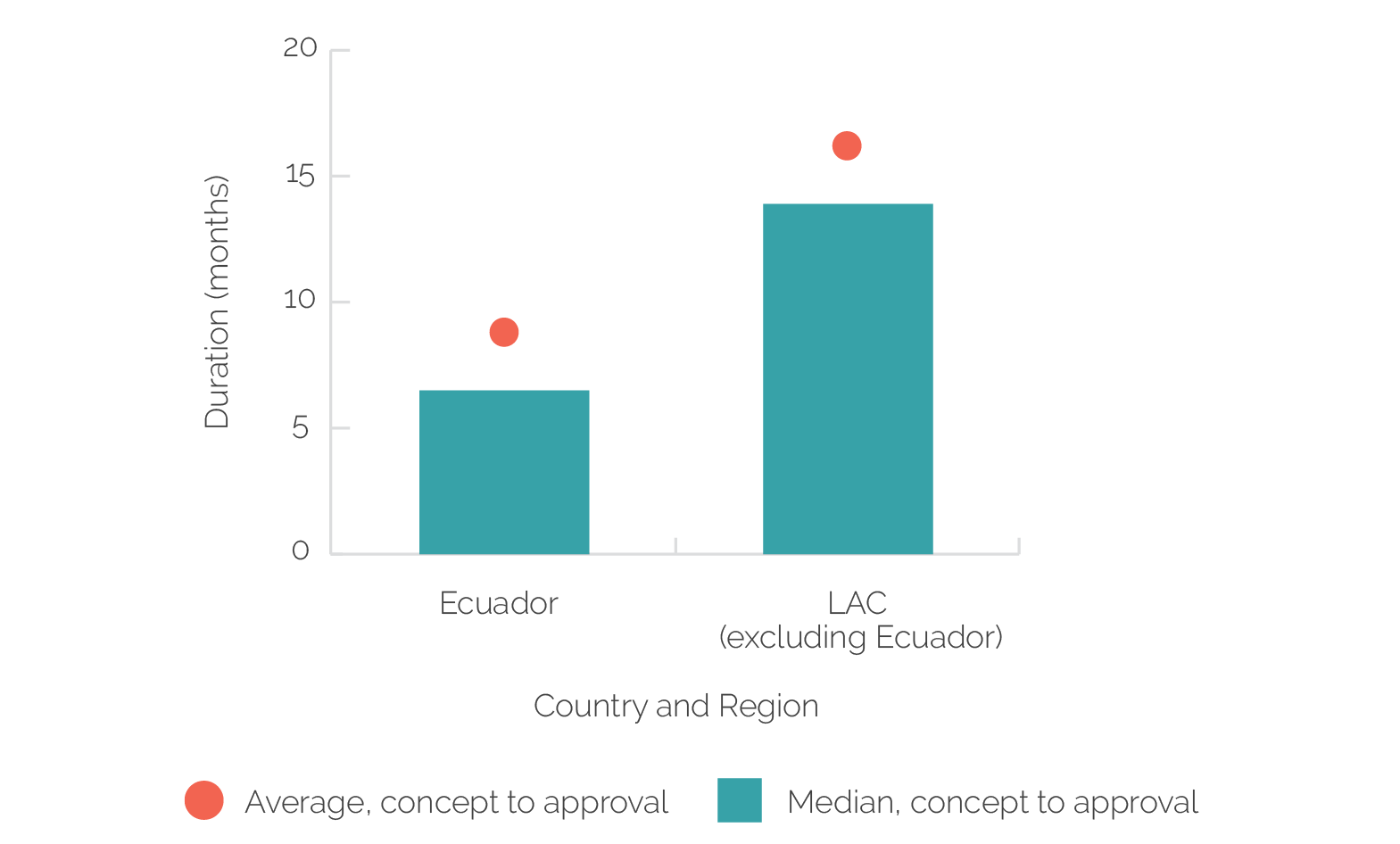

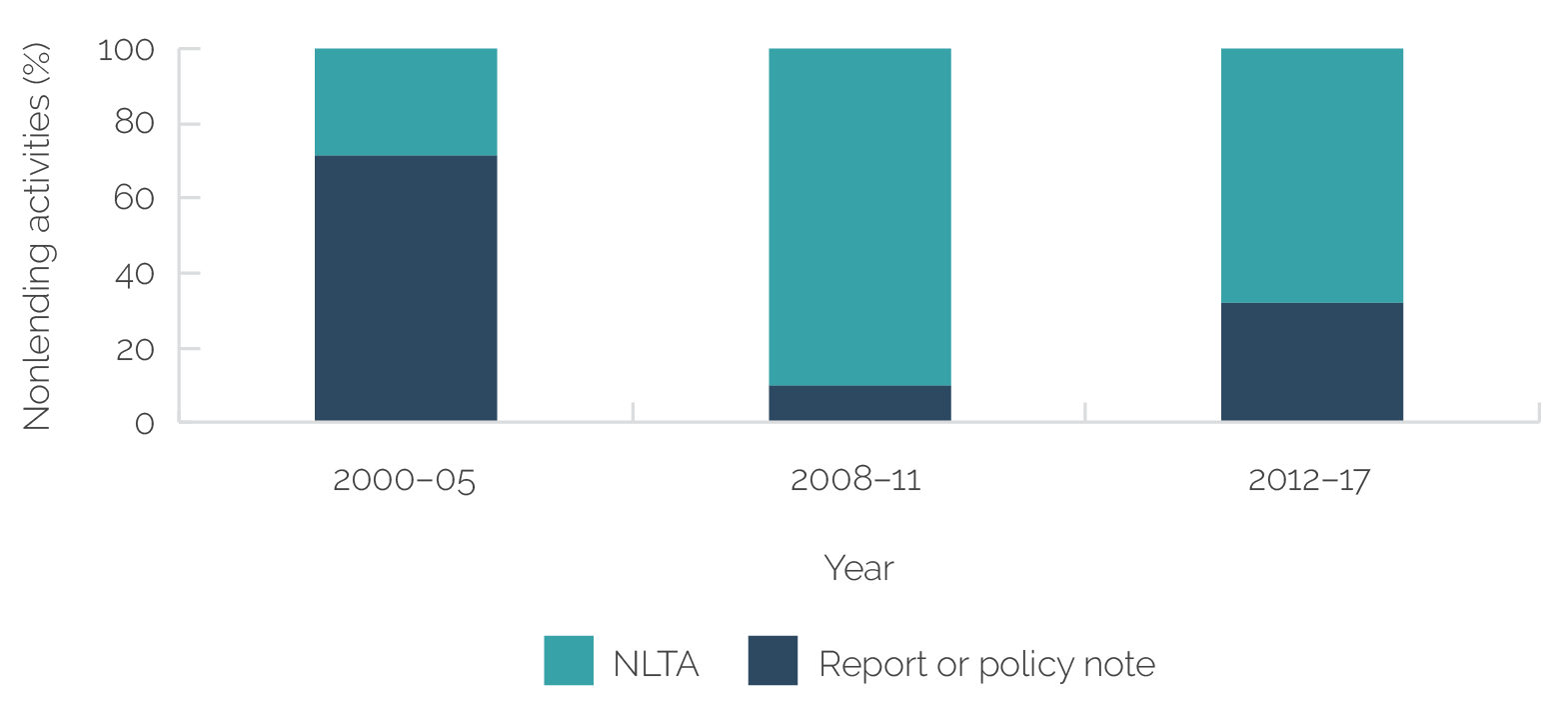

The World Bank built goodwill through discreet or informal activities to meet the government’s desire to limit the World Bank’s visibility. The World Bank’s normalization of relations entailed a significant step back in terms of the World Bank’s visibility, including by shifting its mode of delivery of analytic work toward unpublished NLTA, primarily World Bank financed.19 NLTA captured a range of activities in response to government demand, and it allowed associated tasks to be delivered without a published output. From 2007 through 2017, most of the World Bank’s ASA in Ecuador took the form of NLTA—a significant shift from an earlier emphasis on published reports. Between 2002 and 2005, approximately 75 percent of ASA took the form of published reports or policy notes, with only 25 percent taking the form of NLTA (which were not required to be published). Over 2008–17, however, close to 70 percent of ASA was through NLTA (figure 2.6). This shift responded to the government of Ecuador desire for limited circulation of World Bank analytic work. The World Bank also carefully controlled dissemination of outputs to meet government requests. The Country Economic Memorandum, for example, limited dissemination to specific ministries, but its content was comprehensive, and its messages were candid. The dissemination of other policy notes and reports over the period was similarly contained.

Figure 2.6. World Bank Use of Nonlending Technical Assistance, 2000–17

Source: World Bank portfolio data.

Note: Activities reflect unique project codes. NLTA = nonlending technical assistance.

The World Bank’s operational reengagement demonstrated value in a politically acceptable way. Interviews with country office staff suggest that for several years after the break in dialogue, the government of Ecuador was wary of signaling any visible cooperative relationship with the World Bank (operational or otherwise). With municipal authorities as the official borrowers over the first years of the operational normalization (although the central government provided a guarantee), the World Bank was able to resume operations while preserving the government’s external posture. Municipal infrastructure investments also provided the opportunity for the World Bank to demonstrate comparative advantage as a strategic partner in terms of technical rigor, operational effectiveness, and financial benefits.

However, the World Bank’s prioritization of partnership rebuilding undermined development outcomes. The World Bank’s approach was relevant for partnership rebuilding, but several elements of the strategy came at the expense of development outcomes. Among them are the following:

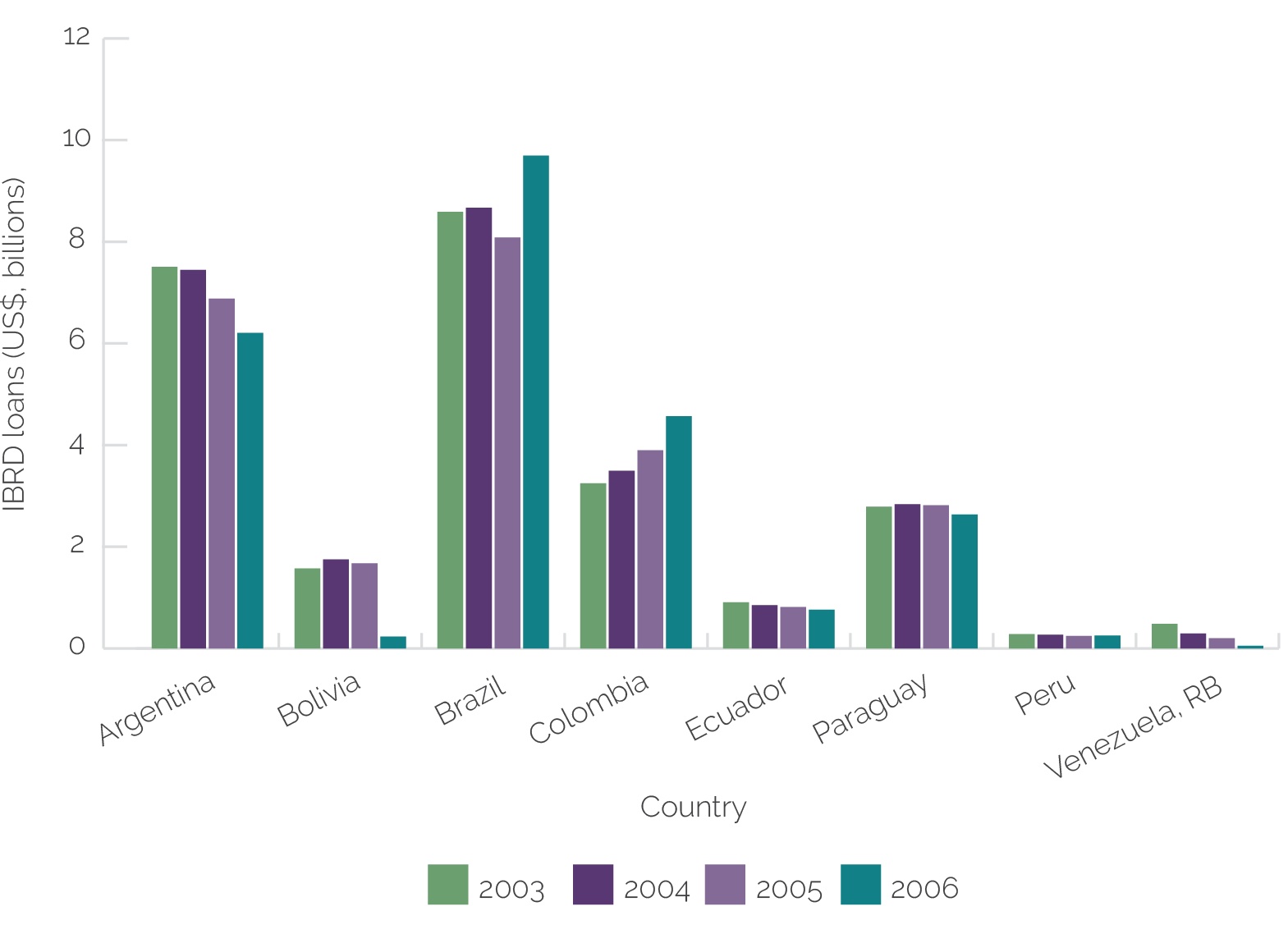

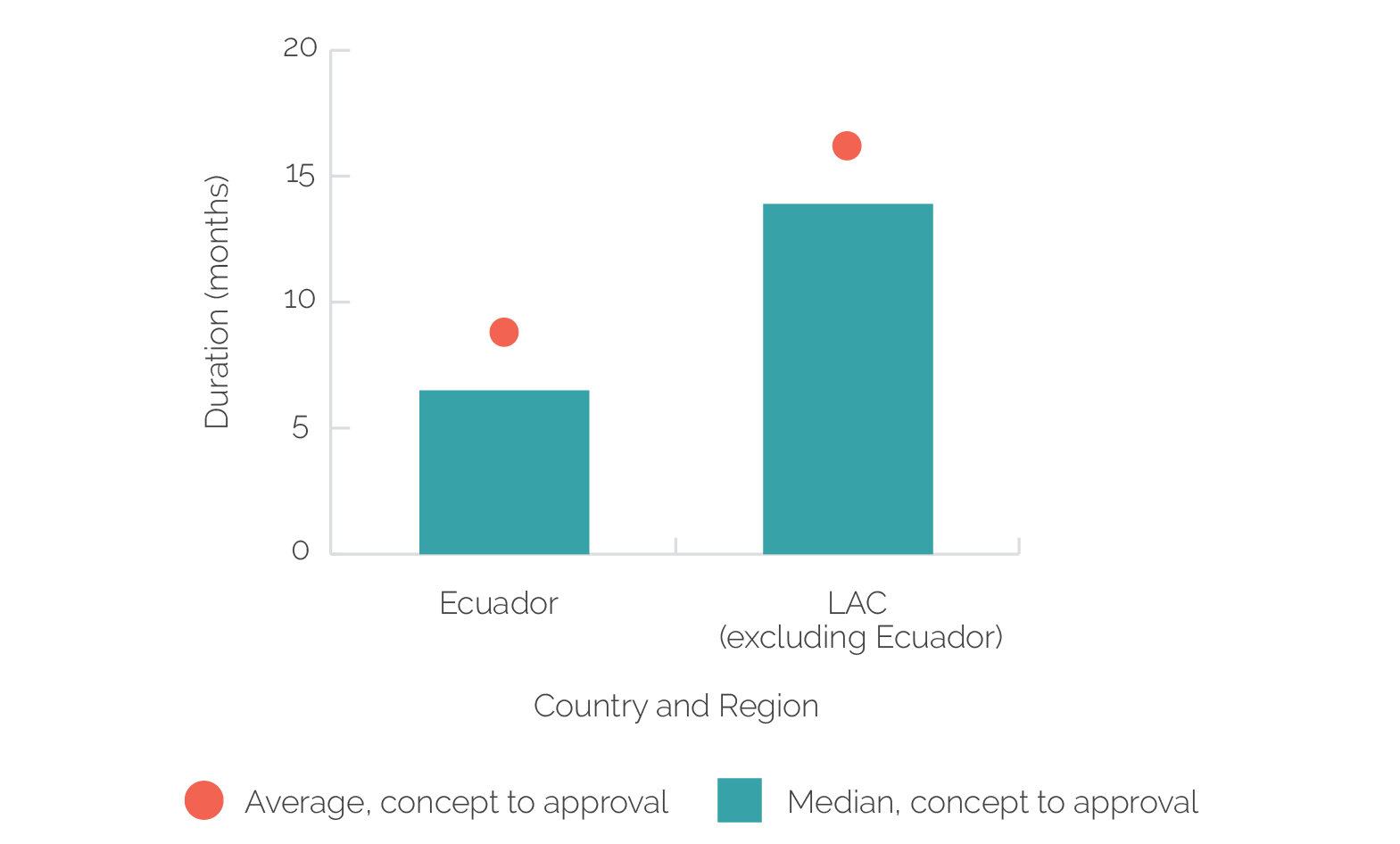

- The World Bank’s quick project preparation came at the expense of project readiness. In preparing the Quito Metro project, the World Bank came in as the last of four multilateral lenders (the other three being CAF, IDB, and the European Investment Bank). As the latecomer in the process, and to meet project delivery deadlines, the World Bank prepared its participation in the Quito Metro project in 5 months. Other operations were also prepared rapidly. The Guayaquil Wastewater Management Project was approved within 4 months from Concept Note review. The Manta Public Services Improvement Project was approved in less than 6 months from Concept Note review. Over the 2007–17 period, the median duration between project concept and approval for the World Bank’s projects in Ecuador was 6.5 months. That compares to a median duration of 13.9 months for other countries in Latin America and the Caribbean (figure 2.7). However, in some cases, the rapid preparation came at the expense of quality engineering designs. After approval of the Ibarra Transport Infrastructure Improvement Project, for example, deficiencies were found in the technical and financial design, making it necessary to substantially revise the project. In Manta, the project was also prepared and approved quickly, given the eagerness of both the municipality and the World Bank, but the subsequent staff self-evaluation acknowledged that project design was underdeveloped at approval. In addition, lack of quality technical studies affected later national infrastructure projects, including both the Ecuador Risk Mitigation and Emergency Recovery Project and the Sustainable Family Farming Modernization Project (which was approved before the subproject designs and feasibility studies were drafted), resulting in the loan not being used for three years.

- The World Bank’s formal strategies neglected to include results frameworks, limiting the World Bank’s accountability for results. Neither strategy approved over the 2007–17 period included a results framework that could articulate higher-level development outcomes by which to measure progress. Reflecting the uncertain nature of the state of dialogue, the ISN for FY14–15 was relatively unspecific about the expected deliverables (beyond the two transport projects close to approval) and presented a menu of potential areas of reengagement, depending on how dialogue progressed. Progress was to be judged in terms of “timeliness of the analytic work, support provided through trust funds, the relevance of World Bank support to the government’s development strategy and policy formulation, and the government’s interest in a continued partnership with the World Bank.” Neither did the CEN for FY16–17 contain a results framework. Although the Bank Group’s short-term strategies do not require results frameworks, there are examples of ISNs and CENs elsewhere that have included both expected outcomes and results matrices, helping establish a clear line of sight between the Bank Group’s support and higher-level goals.20 The inclusion of results indicators would have also better allowed the Bank Group to take midcourse corrective actions where results lagged.

Figure 2.7. Duration between Project Concept Note Review and Project Approval in Ecuador and Latin America and the Caribbean, 2007–17

Source: Independent Evaluation Group staff estimates from World Bank operational data.

Note: LAC = Latin America and the Caribbean.

The World Bank’s partnership rebuilding was slowed by its lack of a clear and consistent approach to working with the government of Ecuador. The World Bank eventually rebuilt a relatively full partnership, but it was slow to define a strategy for working with the government. The World Bank would take six years to approve a strategy. That compares with IDB, which would pivot its country strategy to work with the new administration within a year, and CAF, which had no interruption in relations. Interviews with World Bank country management suggest that the delay in strategy was the result of internal disagreement about the reengagement for the first several years after the break in engagement. The country team supported efforts to establish the preconditions for International Bank for Reconstruction and Development finance, but the World Bank’s credit risk department rejected lending proposals.21 It would be only after 2012, which coincided with the change in World Bank senior management (at the regional and top leadership levels), that the World Bank would formally support renewed lending to Ecuador and a deepened partnership with the national government.

Relevance and Effectiveness to Development Priorities

The World Bank’s reengagement strategy eventually targeted a development agenda that was aligned with the national plan and fell within the scope of priorities identified in earlier diagnostic work. The World Bank’s Country Assistance Strategy (FY03–07) had identified three key agendas that were needed for sustained growth and poverty reduction: macroeconomic stabilization (to lay the foundations for private sector–led growth and address severe liquidity challenges the government of Ecuador was facing in the context of a dollarization framework), inclusive access to economic resources, and strengthened governance and public service delivery (World Bank 2003). Under a distinctly changed development model, the World Bank gradually defined an agenda that supported the national development agenda in politically nonsensitive sectors and that fit within the core objectives of public service delivery and improved access to resources.

Early support toward social protection and nutrition was relevant to the national development agenda. Enhancing social protection aligned with priorities articulated in the government of Ecuador’s national development plan—Plan Nacional para el Buen Vivir. One of the main principles of the Buen Vivir plan was to reduce the gaps constraining inclusive growth through education and health. At the time, chronic child malnutrition was severe, affecting 44 percent of children in the lowest income quintile. Ecuador’s conditional cash transfer program, BDH, was designed to incentivize improved health and education outcomes among poor people through conditional cash transfers to low-income mothers based on required behaviors (including taking children to preventive health checkups and requiring a minimum level of attendance at school for school-age children). Reinforcing Ecuador’s social protection systems more broadly served the objective of reducing poverty and mitigating the impact of later subsidy reforms by strengthening the program’s design, implementation, and monitoring and evaluation.

Support to municipal capacity building was also relevant to improved public service delivery in the context of evolving responsibilities at the local level. Under the country’s Law on Decentralization of the State and Public Participation (1997), reinforced through the new constitution (2008), many functions had been devolved to provincial, district, and parish levels, making capacity building at the local level increasingly important. The World Bank’s DRM support to municipalities aligned with municipal needs as they assumed greater responsibilities, both in the development of DRM strategies and the execution of risk reduction. The World Bank’s NLTA on nutrition (to the province of Chimborazo) served a similar purpose, strengthening subnational capacity in the face of the new requirements imposed by decentralization. At the operational level, the World Bank’s support to infrastructure development focused on Buen Vivir’s objectives for quality of life for the population and access to work, among others; support toward water and sanitation was relevant to identified priorities for poverty alleviation.

However, operations did not adequately account for low institutional capacity. World Bank projects over the operational normalization period did not adequately account for capacity constraints, leading to significant delays in project implementation (discussed further in this section). IEG’s evaluation of the Manta Public Services Improvement Project noted that the project implementation unit (PIU) had no previous experience with World Bank procedures and faced huge coordination challenges because the project involved the Manta public water authority and six municipal directorates (World Bank 2022a). Most of the other municipality projects faced similar challenges. Interviews with government counterparts over the period suggest that the World Bank did not provide the level of support needed for effective implementation. According to one PIU coordinator, “the country lost the expertise to implement World Bank projects. The World Bank’s procurement team provided training to the PIU, but insufficient to deal with the rotation in PIU staff that comes with a change in government administration.”

The national government’s absence from subnational projects heightened the need to build subnational implementation capacity. National authorities often play a pivotal role in the effective delivery and scaling up of subnational infrastructure initiatives. They can directly support subnational agencies in project implementation, share best practice experiences on financing and delivery, facilitate authorizations and approvals, and adapt national laws, regulations, and institutions to ensure more effective project implementation. However, the deliberate hands-off role of the national government during the period of the World Bank’s subnational lending increased the need for institutional capacity building.

World Bank projects over the reengagement period were generally effective. Only four World Bank projects approved over the operational normalization period closed and had their staff self-evaluations validated by IEG (three other projects closed in December 2023 and have not yet been evaluated). Of these, three were rated moderately satisfactory for project outcomes, with one (Ecuador Risk Mitigation and Emergency Recovery Project) rated moderately unsatisfactory (table 2.1).

Table 2.1. Independent Evaluation Group Project Ratings for Closed Projects Undertaken between Fiscal Years 2007 and 2017

|

Project Name |

Relevance |

Outcome |

Efficiency |

Bank Performance |

|

Chimborazo Development Investment Project |

Substantial |

MS |

Modest |

MS |

|

Manta Public Services Improvement Project |

Substantial |

MS |

Substantial |

MS |

|

Supporting Education Reform in Targeted Circuits |

High |

MS |

Modest |

MS |

|

Ecuador Risk Mitigation and Emergency Recovery Project |

Substantial |

MS |

Modest |

MU |

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: The Independent Evaluation Group’s validation of the Supporting Education Reform in Targeted Circuits project has not yet been conducted, and the scores shown reflect the self-evaluation ratings from country teams. Relevance for development policy operations is based on relevance of prior actions. MS = moderately satisfactory; MU = moderately unsatisfactory.

The bulk of the World Bank’s municipal infrastructure projects achieved their outcome objectives. The Chimborazo Development Investment Project increased production and market access of rural families. Annual production and average family incomes increased, and vehicle operating costs and travel times declined, although the project did experience cost overruns, and assessed benefits were lower than anticipated. The Manta Public Services Improvement Project expanded the quality of water supply and sanitation services to the city in terms of continuity of service, access, and availability, and roads construction improved the quality and sustainability of urban mobility. There were shortcomings in achieving the financial sustainability of water supply and sanitation services.

World Bank projects near closure are also expected to achieve their objectives. According to the latest Implementation Status and Results Reports, recently closed and active projects approved over the reengagement period are likely to achieve their targeted results. The Quito Metro project (which closed in December 2023 but has not yet been evaluated) resulted in the construction and eventual operation of a universally accessible underground line that is expected to enhance citywide transport choices. Commercial operations began at the end of 2023, and several project development objectives related to capacity, reduced transport times, and accessibility have been achieved.22 The Implementation Status and Results Reports for the Guayaquil Wastewater Management Project (closing FY26) suggest that substantial progress has been made toward two-thirds of outcome indicators related to beneficiaries,23 although outcomes related to pollution loads removed and extent of pro-poor service provision have not yet been achieved (World Bank 2023a).

However, World Bank projects suffered delays of 60 percent during the ISN period because of municipal capacity issues. Of the three projects approved over the ISN cycle, the Manta Public Services Improvement Project closed with a delay of 2.5 years, bringing the implementation period from 4 to 6.5 years (more closely reflecting the average time for an investment project); the Quito Metro project closed with a delay of 3 years (from 5.25 to 8.25 years, from effectiveness to closure); and the Guayaquil Wastewater Management Project remains open, with an expected increase in implementation of 3 years (from an expected implementation of 7.5 to 10.5 years).24 The average implementation delays over the ISN period were 60 percent for closed projects and 40 percent for the open project (figure 2.8). ISN project delays can be linked to implementation capacity issues, including inefficiencies in Ecuador’s budgeting process and restrictions in financial management systems, which impeded the timely disbursement of funds. In the case of Manta, underdeveloped designs at approval also impeded implementation (with designs requiring subsequent revision). Finally, restrictions stemming from the COVID-19 pandemic also affected implementation, particularly in Quito and Guayaquil.

Figure 2.8. Increase in Implementation Time of World Bank Investment Projects in Ecuador by Period of Project Approval

Source: Independent Evaluation Group estimates from review of portfolio.

Note: CEN = Country Engagement Note; CPF = Country Partnership Framework; ISN = Interim Strategy Note.

Implementation delays persisted during the CEN cycle, despite the portfolio’s shift to national-level projects. The shift to national-level projects after FY15 reduced some of the project implementation delays, with delays over the CEN cycle among closed projects almost halved from the ISN cycle. However, project implementation continued to suffer delays that averaged more than twice the Latin America and the Caribbean average. Among open projects approved over the ISN and CEN cycles, the average disbursement lag (over the planned timeline) was 50 percent. All projects approved between 2007 and 2017 experienced implementation delays—the result of both weak implementation readiness and changes in leadership that resulted in shifting priorities.25

Political turnover within subnational governments accelerated institutional capacity losses and stalled project implementation. A high degree of subnational government turnover created further challenges for World Bank projects, not only through the loss of technical capacity of implementing units but also through substantial shifts in subnational government priorities. Over the implementation of the Quito Metro project, for example, the mayor changed three times. As a result, although almost all the civil works associated with the metro line were successfully completed by 2019, it would not be until December 2023 that commercial operations began because two essential conditions for achievement of outcomes—the award of contracts for operation and fare collection—were not realized promptly. At the time of project approval, the municipality had outlined its business model for public sector operation of the metro. However, midway through construction (and under a new mayor), the municipality shifted plans and sought a private sector operator instead. With political instability and staff turnover, the PIU was unable to defend its decisions on the approval of a private operator to the new government with technical and legal arguments, stalling the process for years.

The Bank Group missed opportunities to mitigate known institutional capacity risks. There were several opportunities in the project cycle (over preparation and implementation) to mitigate known capacity risks, but the Bank Group never took appropriate steps to do so. The Bank Group missed three main opportunities for mitigating risks:

- The World Bank did not outline mitigation measures within its formal strategies. The ISN did not outline specific mitigation measures for known implementation capacity constraints; however, at the time of its drafting, two projects in the province of Chimborazo—a World Bank–financed project for rural roads and irrigation and a small trust fund–financed project for nutrition—were under implementation, and both exhibited weak capacity in implementing entities. Although the ISN noted these delays, it did not outline specific support to address institutional capacity weaknesses and procedural differences in working at the subnational level beyond the World Bank’s “due diligence” of regular procurement training and close supervision.

- The World Bank did not use additional financing requests to include effective stipulations that could reduce risks. The Quito Metro project was significantly delayed when municipal authorities shifted their plans from a public sector to a private sector operator. With political instability and staff turnover, the PIU was unable to defend decisions on the approval of a private operator to the new government for several years. Although at the time of the Quito Metro project approval, the World Bank could not have foreseen the change in operator plans, this information was known by 2018 when the World Bank approved an additional financing for the metro. At that time, it had the opportunity to include covenants to ensure that an agreement on the operator was reached before disbursement, but it did not.

- The Bank Group did not leverage IFC’s expertise to guide the Quito Metro authority. The risks involved in a delayed metro operation were high, with all of the intended benefits dependent on the metro being fully operational. Even without IFC direct investment in the eventual operator or a formal advisory transaction, a limited informal engagement by IFC to advise and share knowledge and experience could also have been instrumental in moving the process forward.

- The value of Ecuador’s International Bank for Reconstruction and Development loans in 2003 in per capita terms was $68, higher than Brazil ($47), Paraguay ($52), and República Bolivariana de Venezuela ($18), and not markedly lower than Colombia ($79).

- The Second Indigenous and Afro-Ecuadorian Peoples Development Project was the follow-up to an earlier project (fiscal year [FY]02), at the time considered by the government as the model for the promotion of local development in rural and peri-urban areas (and with outcomes rated satisfactory by the Independent Evaluation Group).

- The $32 million Rural Roads Project, for example, in which the World Bank was to finance $20 million, was approved in July 2006 and never became effective. The $76 million National Rural Water Supply and Sanitation Project, in which the World Bank was to finance $48 million and that built on a previous phase, was declared effective in December 2006. It had serious implementation issues because of diverging points of views between the government and the World Bank on how and what to implement. A significant part of the loan amount was canceled. It was prematurely closed in March 2009 with only $7.5 million of World Bank financing disbursed.

- In December 2023, the government of Poland dismissed the World Bank’s representative.

- After the default, in the midst of the global financial crisis and as bond prices dropped, Ecuador began a program of repurchasing them through financial intermediaries, ultimately buying back 91 percent of the bonds at 35 cents on the dollar (Feibelman 2017).

- The objectives guiding the World Bank’s decisions (and hence the theories of change to reach those objectives) were reconstructed based on analysis of program documentation and interviews with World Bank regional and country management, country office staff, and World Bank task team leaders over the period, with World Bank interview information corroborated through interviews with contemporaneous government authorities, where pertinent.

- No high-level talks were initiated on President Correa’s election to the presidency in October 2006 (despite mounting public rhetoric against the World Bank’s earlier actions). The World Bank Group did not send a high-level representative to his inauguration (although both the Inter-American Development Bank and Banco de Desarrollo de América Latina y el Caribe did so). The absence of attempts to defuse the confrontation directly suggests ambivalence on the part of the World Bank to the normalization process over the early years.

- In April 2007, Hugo Chávez announced withdrawal of República Bolivariana de Venezuela from the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank. Both the World Bank and the 48 The World Bank Group in Ecuador Chapter 2 International Monetary Fund closed their offices in Caracas, although República Bolivariana de Venezuela would ultimately not formally withdraw from either institution.

- Child Development nonlending technical assistance (FY08).

- After the passage of the 2010 Organic Code of Production, Commerce, and Investment, the Coordinating Ministry for Production, Employment, and Competitiveness was tasked with implementing Ecuador’s transformation of the productive matrix. The main goal was to transform production away from natural resources and imports and to incentivize local production and systems of innovation and entrepreneurship.

- Chimborazo Development Investment Project (FY08).

- The nonlending technical assistance on disaster risk management to Quito would lead to a small $0.8 million World Bank–executed project, financed through the World Bank’s Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery, a trust fund established in 2006 to help low- and middle-income countries reduce vulnerabilities to natural hazards and climate change.

- For example, according to the two country directors from 2007 to 2011 and from 2011 to 2014, the country manager appointed in 2010 was entrepreneurial in initiating low-level dialogue at social events that government ministry staff attended.

- Lenín Moreno, the vice president of Ecuador from 2007 to 2013, pushed strongly for disability rights, in part stemming from his personal experience as a paraplegic.

- For example, the United Nations Development Programme hosted an international conference on disaster risk management in Guayaquil in 2014, which provided one of the first opportunities for the World Bank to engage with the mayor, an engagement that would ultimately lead to a municipal-level wastewater management operation.

- Ecuador Transport nonlending technical assistance.

- Ecuador Risk Mitigation and Emergency Recovery Project (P157324).

- President Correa was not eligible for reelection in 2017.

- A total of 69 percent of the spending associated with analytic work delivered over the 2008–17 period was financed by the World Bank.

- See, for example, Libya Country Engagement Note FY19–21, South Sudan Country Engagement Note FY18–19, the Republic of Yemen Country Engagement Note FY20–21, Haiti Independent Evaluation Group World Bank Group 49 Interim Strategy Note FY13–14, Madagascar Interim Strategy Note FY12–13, and Tunisia Interim Strategy Note FY13–14.

- International Bank for Reconstruction and Development financing requires adequate creditworthiness, which was absent after the bond default at end 2008 when Ecuador’s rating from S&P Global (formerly Standard & Poor’s) declined to below investment grade (CCC). However, even when Ecuador’s credit rating rose and stabilized (by August 2010), the World Bank management remained unsupportive of operations financed by the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development to Ecuador until after 2012.

- According to the December 2023 staff implementation report, within the first two weeks of operation, the number of passengers per day had met 45 percent of the targeted change, travel time reduction had met its target, the operating cost reduction for Quito’s vehicle fleet was 45 percent of the targeted change, the reduction in emissions was 22 percent of the targeted change, and targets had been met for passenger capacity and satisfaction, satisfaction among female users, and percent of jobs accessible within one hour of travel time.

- With more than half of the targeted change in the outcome indicator achieved by December 2023.

- However, the bulk of the extension relates to a scale-up in activities from an additional financing request.

- For example, the national-level Sustainable Family Farming Modernization Project was restructured twice because of delays in most subprojects (irrigation works, training plans, and delivery of agri-environmental investment). The World Bank’s Transformation of the Tertiary Technical and Technological Institutes Project experienced delays averaging more than 40 percent to date, with significant delays in civil works in several provinces, blocking the advancement of other components. A level 2 restructuring canceling part of the loan, changing implementation arrangements, and reducing the number of provinces supported by the project, along with a subsequent request to extend the closing date, improved disbursement rates.