The World Bank Group in Ecuador

Chapter 1 | Background and Context

Introduction

This Country Program Evaluation (CPE) assesses the relevance and effectiveness of the World Bank Group’s support to Ecuador from fiscal year (FY)08 to FY22. Specifically, it examines the evolution of the Bank Group’s support to Ecuador after a structural break in the World Bank’s partnership with the government of Ecuador in 2007—one in which dialogue was severely circumscribed and World Bank lending ceased. The evaluation examines Bank Group’s support along two fronts. First, it examines the process by which the World Bank restored a productive partnership with the government of Ecuador after 2007 and assesses that approach in terms of relationship strengthening and development effectiveness. Second, it examines Bank Group’s support for the government of Ecuador’s rebalancing after 2017 from a state-led development model to an economic growth model that could support an expanded, dynamic, diversified, and resilient private sector while protecting the vulnerable over the transition.

Overall, the report finds that the Bank Group’s support to Ecuador was relevant and generally effective despite a difficult relationship with the government. The evaluation period was defined by two major stages. During the first stage, from 2007 to 2017, the World Bank provided low-visibility support to gradually reestablish a constructive partnership with the government after a near-total break in relations in 2007. During the second stage, after 2017, the World Bank worked with a new government to help rebalance the government’s development model toward more sustainable state spending and private sector–led growth. Over the evaluation period, the Bank Group’s support to Ecuador was both relevant to the country’s development priorities and appropriate to the constraints of the evolving partnership with the government. However, the World Bank underestimated institutional capacity constraints and political economy challenges, leading to project implementation days and policy reversals.

The report is organized into five chapters. The remainder of chapter 1 introduces Ecuador’s development context and highlights the government of Ecuador’s shifting development policy agenda over the period. The chapter then introduces the evaluation design and methodology. Chapter 2 investigates and evaluates the process by which the World Bank normalized its relationship with the government after the structural break in relations beginning in 2007. Chapter 3 assesses the relevance and effectiveness of the Bank Group’s support for Ecuador’s rebalancing to a sustainable, private sector–led growth model. Chapter 4 assesses the relevance and effectiveness of the World Bank’s complementary support toward improved protection of poor and vulnerable people over the government of Ecuador’s transition to a private sector–led growth model. Chapter 5 presents the conclusions emerging from the evaluation’s evidence and lessons to help inform future Bank Group support to Ecuador.

Economic Context

Ecuador is a small, middle-income country straddling the equator, with an ethnically diverse population of 18 million people. The country encompasses a wide range of landscapes and climates, including coastal deserts, mountains, and rain forests. Ecuador’s income per capita in 2022, at $6,400, puts it at about 75 percent of the average for Latin America and the Caribbean countries (up from about 50 percent of the average in 2007)1 and about on par with all middle-income countries.

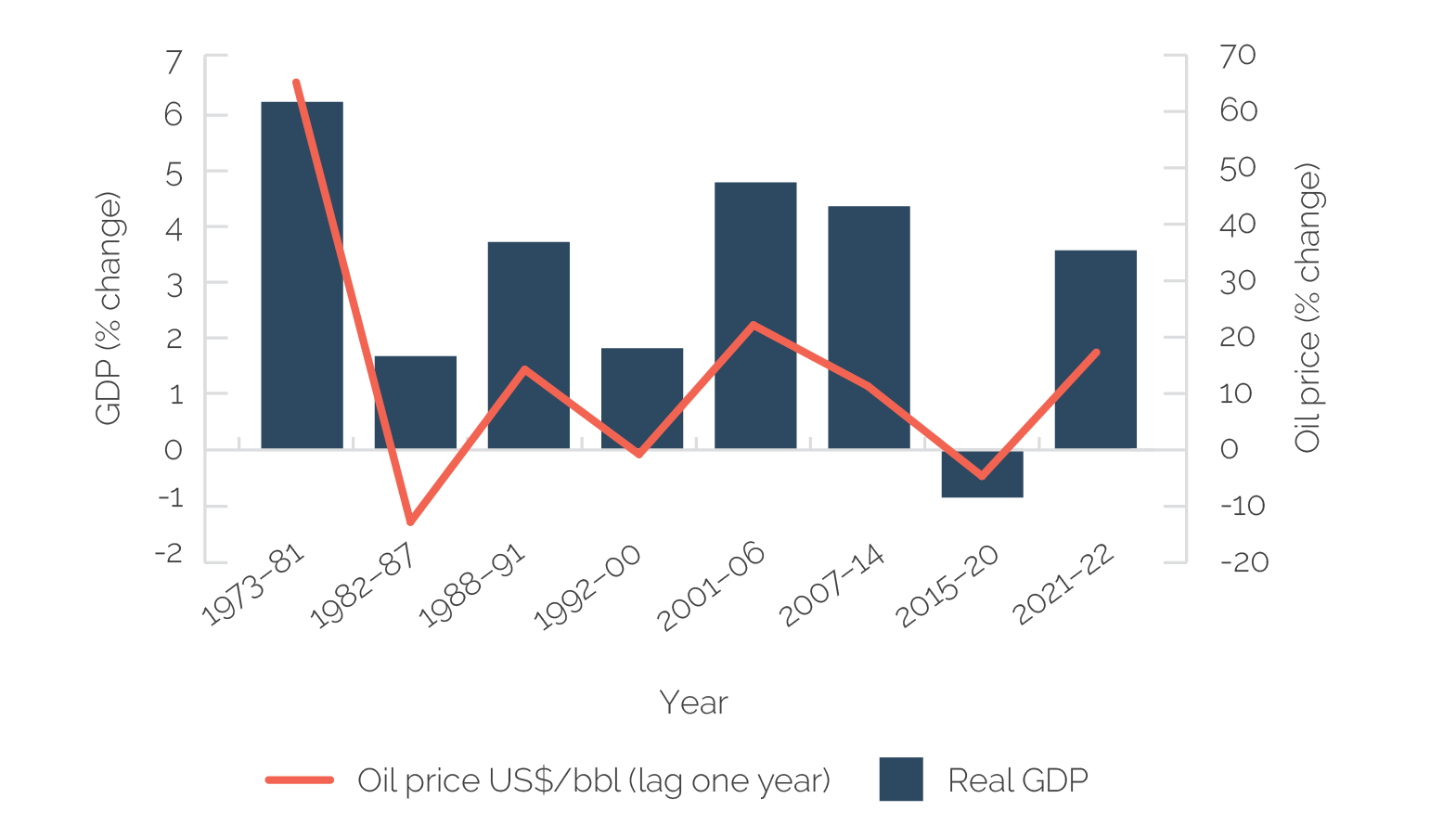

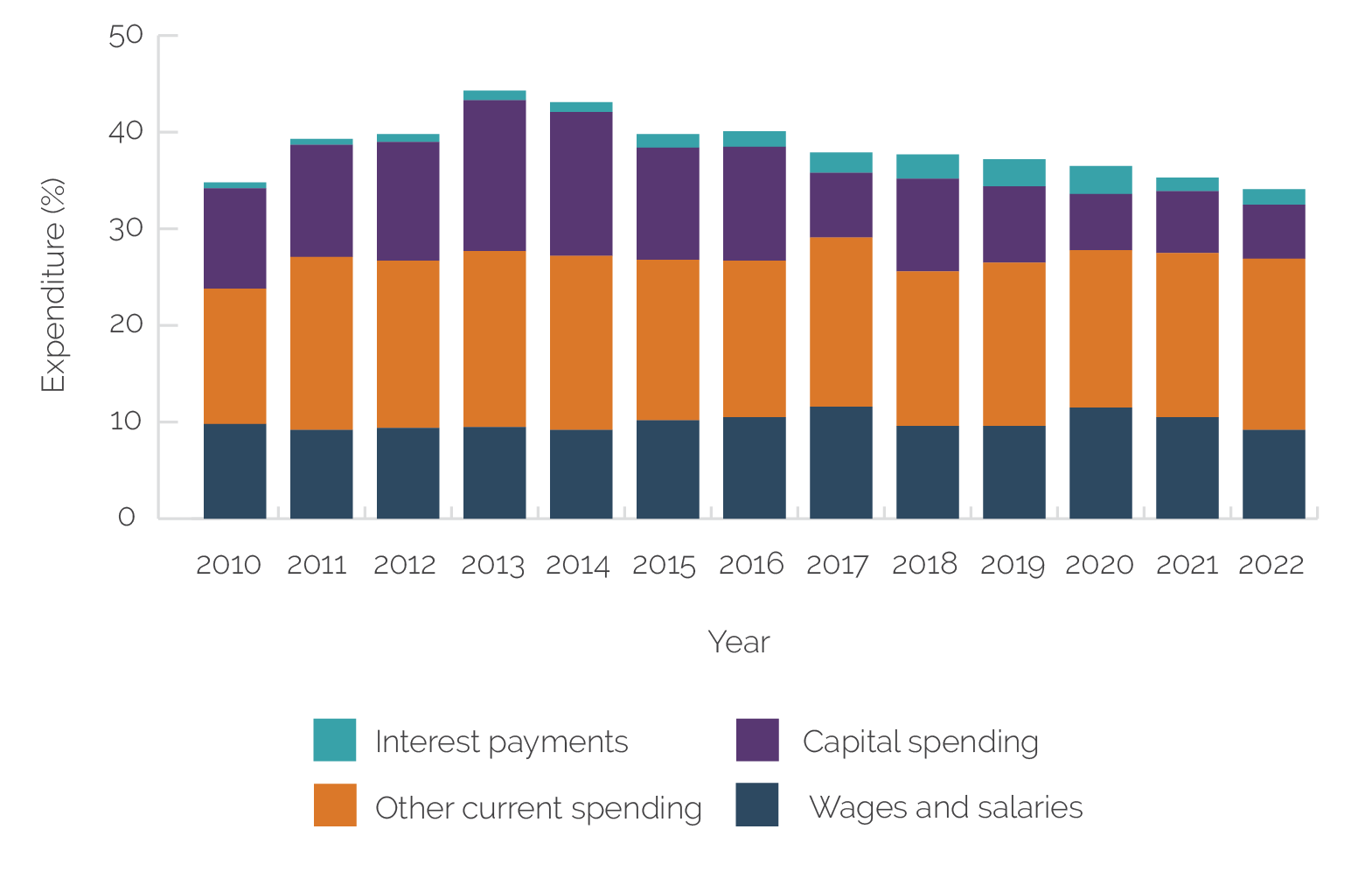

Ecuador’s oil exports have driven its economic performance and public finance outcomes. Ecuador became an oil exporter in 1972. Since then, oil market developments have driven economic growth (figure 1.1). In 2006, petroleum sales represented about 60 percent of goods exports and 27 percent of fiscal revenues (IDB 2008), leaving Ecuador highly vulnerable to commodity price shocks. The abundance of oil has discouraged investment in economic diversification (Orozco Espinel 2019), intensifying the vulnerability to oil price changes.

Figure 1.1. Average Annual Changes in Real GDP and Oil Prices

Source: World Development Indicators data (real GDP) and World Bank commodity price data (annual average, Dubai, Brent, and West Texas Intermediate).

Note: bbl = barrel.

Ecuador is at high risk of natural hazards. More than two-thirds of the population live in areas subject to natural hazards, including floods, landslides, droughts, volcanic eruptions, and earthquakes (GFDRR 2010). The majority of the population live in the mountainous and coastal areas most vulnerable to natural disaster. In 2016, in the midst of dealing with impacts from the El Niño phenomenon, Ecuador was struck by a 7.8 magnitude earthquake, resulting in 676 deaths, 6,274 injuries, and 80,000 displacements, as well as $3.3 billion in reconstruction costs, $515 million in losses in the productive sector, and 21,823 job losses (World Bank 2022d). Creating greater resilience to its ongoing natural disaster risks is thus a continuing priority to safeguard Ecuador’s development.

In the early 2000s, Ecuador was emerging from an economic and financial crisis. Fueled by a string of domestic economic factors (including fiscal rigidities, the accumulation of high levels of dollarized debt in a weakly regulated financial sector, and institutional weaknesses)2 and external shocks (including depressed oil prices, widespread crop failures stemming from El Niño, and a worldwide shrinking of external credit), Ecuador experienced a sharp reversal of capital inflows over the late 1990s, which triggered financial instability and economic stagflation. As oil prices bottomed out to below $20 per barrel, the government deficit ballooned to 6.2 percent of GDP, output contracted by 7 percent, and Ecuador defaulted on its Brady bonds. A number of leading financial institutions were shut down between 1998 and 2000, and in March 1999, the government ordered bank deposits frozen. Annual inflation reached 52 percent, causing Ecuador’s national currency to depreciate rapidly. The social impacts of the crisis were significant. Between 1998 and 1999, unemployment doubled from 8.5 percent in May 1998 to 16.9 percent in June 1999 (IDB 2008), real wages declined by about 25 percent, and the poverty head count ratio at $3.65 per day rose from 40.5 percent to 50.3 percent. The crisis also caused massive migrations, with approximately 400,000 Ecuadorans migrating to the United States between 1999 and 2000.

There were deep social divisions around the country’s fiscal reforms to address the crisis. The 1999 crisis was addressed by a significant fiscal contraction exercise through a series of fiscal austerity and revenue-raising measures—accompanied by a $300 million Stand-By Arrangement with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in 2000. Most important among the actions taken to deal with the crisis was the government of Ecuador’s decision to dollarize in January 2000. Taken together, the measures lowered inflation and improved fiscal and debt balances. The reform agenda—most importantly, the dollarization decision—was initially met by widespread social opposition, ultimately leading to the removal of then-president Jamil Mahuad from office. Over time, dollarization gained broader support, but the crisis exposed a profound lack of consensus internally about Ecuador’s policy reform agenda.

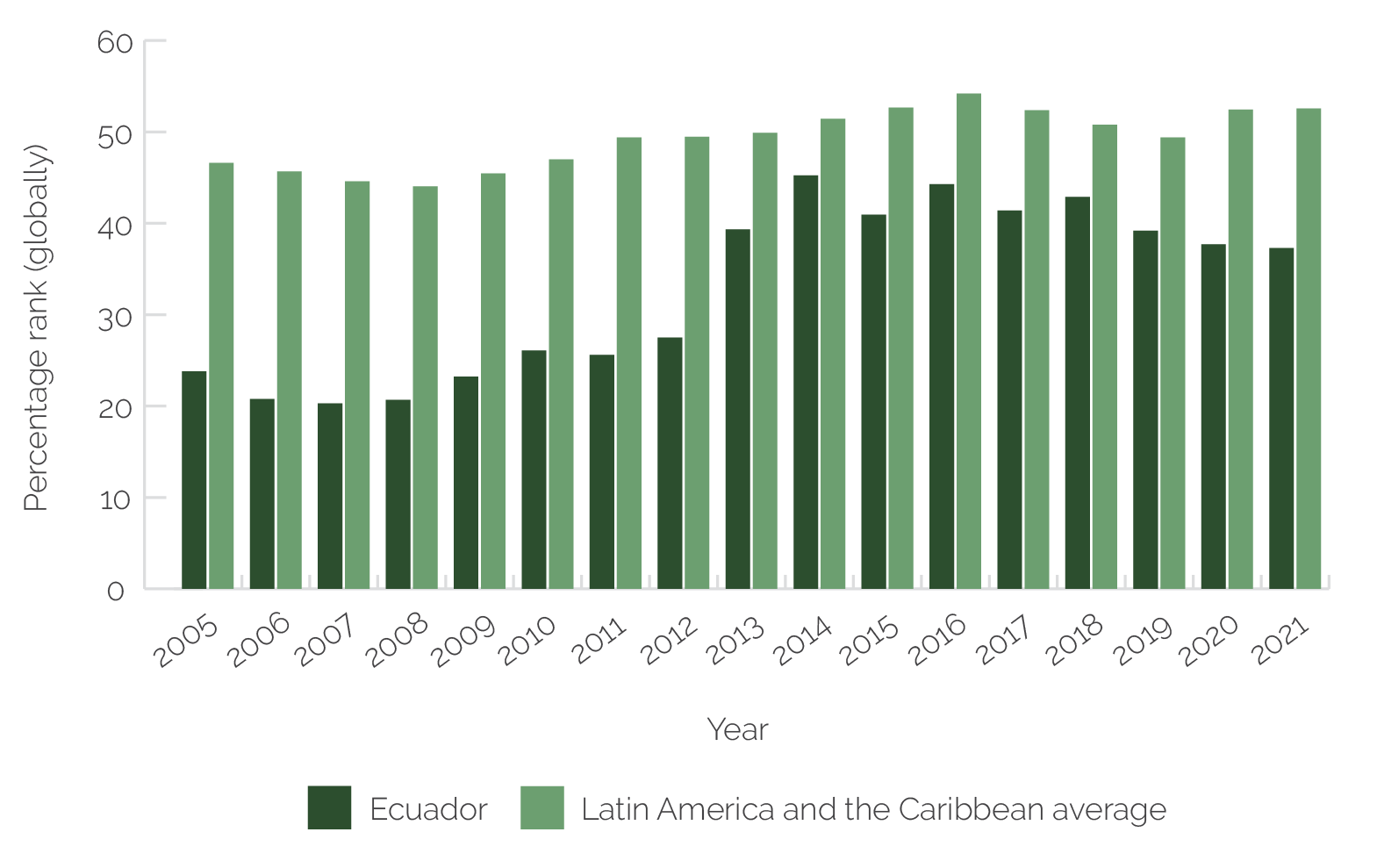

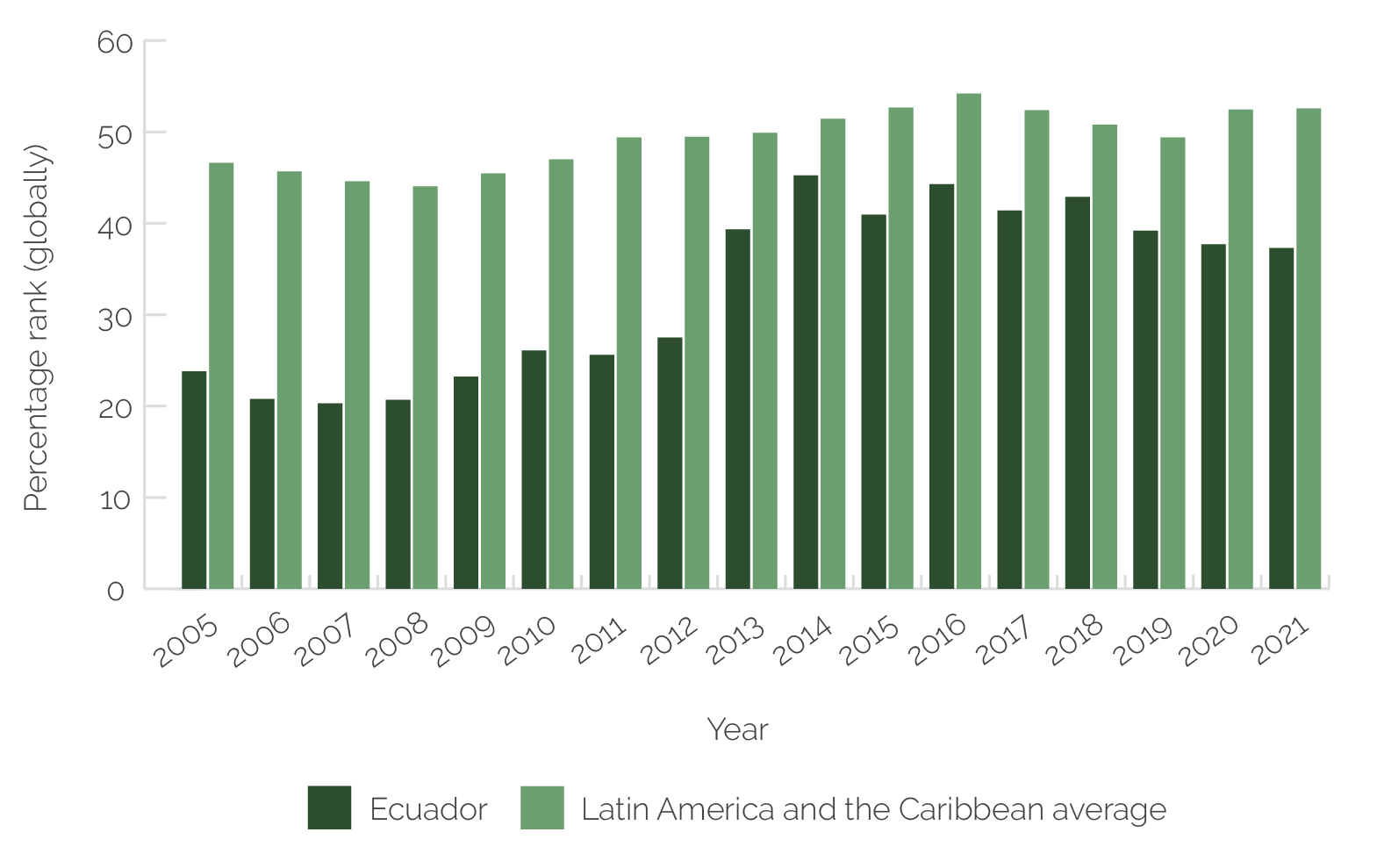

Ecuador’s socioeconomic fragmentation has led to inconsistent economic policies and political instability. In the decade before 2007, Ecuador had eight presidents, none of whom remained in office for a full term. Although constitutional processes of succession were observed throughout the political turmoil, each would be removed from office and replaced by a vice president for the remainder of the term. Intense socioeconomic fragmentation between the Coast region (including Guayaquil, the largest city and economic core) and the Sierra region (including Quito, the capital and center of political administration) is reflected by distinct and often opposed views about the route of development that Ecuador must follow (Jácome 2004), resulting in political instability. According to the World Bank’s Worldwide Governance Indicators, Ecuador had one of the lowest levels of political stability in the region during the 2000s (figure 1.2), which has made it difficult to pursue a coherent economic policy. Divided and powerful groups within civil society (including Indigenous groups) create challenges for implementing and sustaining policy reforms.

Figure 1.2. Political Stability in Ecuador versus Latin America and the Caribbean

Source: Worldwide Governance Indicators (database), World Bank.

Note: The Worldwide Governance Indicators database is a research data set summarizing the views on the quality of governance provided by a large number of enterprise, citizen, and expert survey respondents in industrial and developing countries. These are gathered from survey institutes, think tanks, nongovernmental organizations, international organizations, and private sector firms. They do not reflect the official views of the World Bank, its executive directors, or the countries they represent and are not used by the World Bank to allocate resources.

Ecuador’s Development Policy and Economic Performance, 2007–22

Ecuador’s development agenda from 2007 to 2022 is characterized by two distinct phases. Between 2007 and mid-2017, the country’s development model pivoted away from an open-market approach to one that enhanced state participation in the economy—increasing its regulatory and planning power—and promoted greater equity through greatly enhanced social spending. Beginning in mid-2017, with deteriorating economic conditions and a new government, revisions to that model reduced the state’s role in the economy, sought to put the country on a more sustainable fiscal path, and undertook reforms to enhance private sector–led growth. External conditions also changed markedly over the two phases of the development agenda. Over the 2007–14 period, Ecuador’s economy benefited from record high oil prices, boosting economic growth and public revenues. After 2014, oil prices fell sharply (dropping 50 percent between mid-2014 and end of 2019), and COVID-19 brought a collapse of global demand and oil prices, severely affecting Ecuador’s economic performance and macroeconomic outcomes.

Buen Vivir, 2007–17

The government of Ecuador’s Buen Vivir development model from 2007 to 2017 emphasized human development, national sovereignty, and citizen participation in the public sphere. The new government administration that took office in 2007 viewed many of the stabilization and structural adjustment policies promoted by multilateral financial institutions as contributing to the economic crises experienced by the country over the earlier two decades. Under President Rafael Correa, the government of Ecuador launched the Plan Nacional para el Buen Vivir (National Plan for Good Living), which articulated a strong focus on poverty reduction, health, national sovereignty, and citizen participation in the public sphere (box 1.1).

Box 1.1. Core Objectives of the Plan Nacional para el Buen Vivir

- Foster social and territorial equality, cohesion, and integration, while respecting diversity.

- Improve citizens’ capacity and potential.

- Improve quality of life for the population.

- Guarantee the rights of nature and promote a healthy and sustainable environment.

- Guarantee sovereignty and peace and promote strategic insertion in the world and in Latin America.

- Guarantee stable, fair, and dignified work in its diverse forms.

- Build and strengthen public and intercultural places.

- Affirm and strengthen national identity, diverse identities, and a plurinational and intercultural state.

- Guarantee human rights and social justice.

- Guarantee access to public and political participation.

- Establish a social, inclusive, and sustainable economic system.

- Build a democratic state to promote “el buen vivir.”

Source: World Bank 2013.

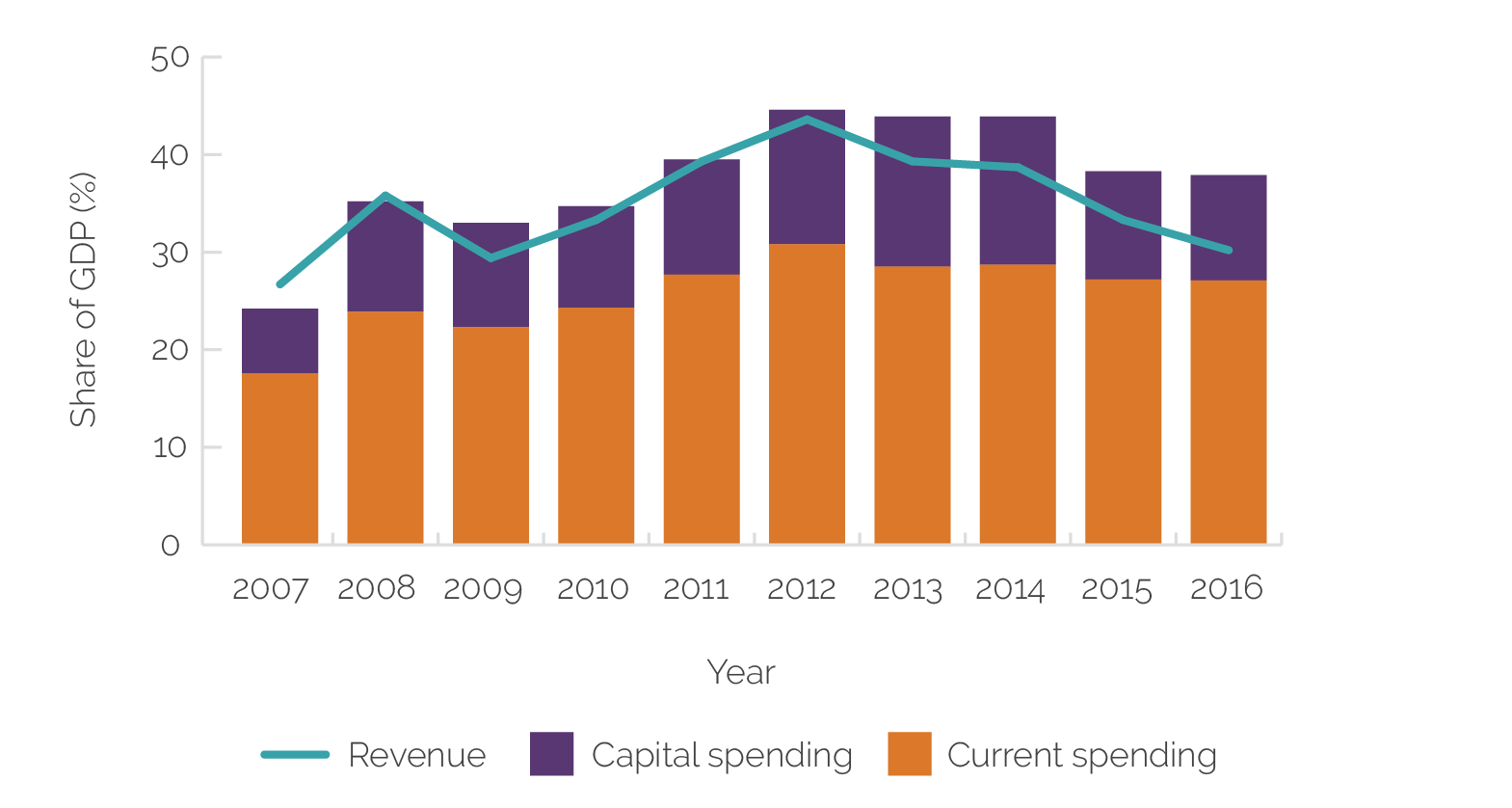

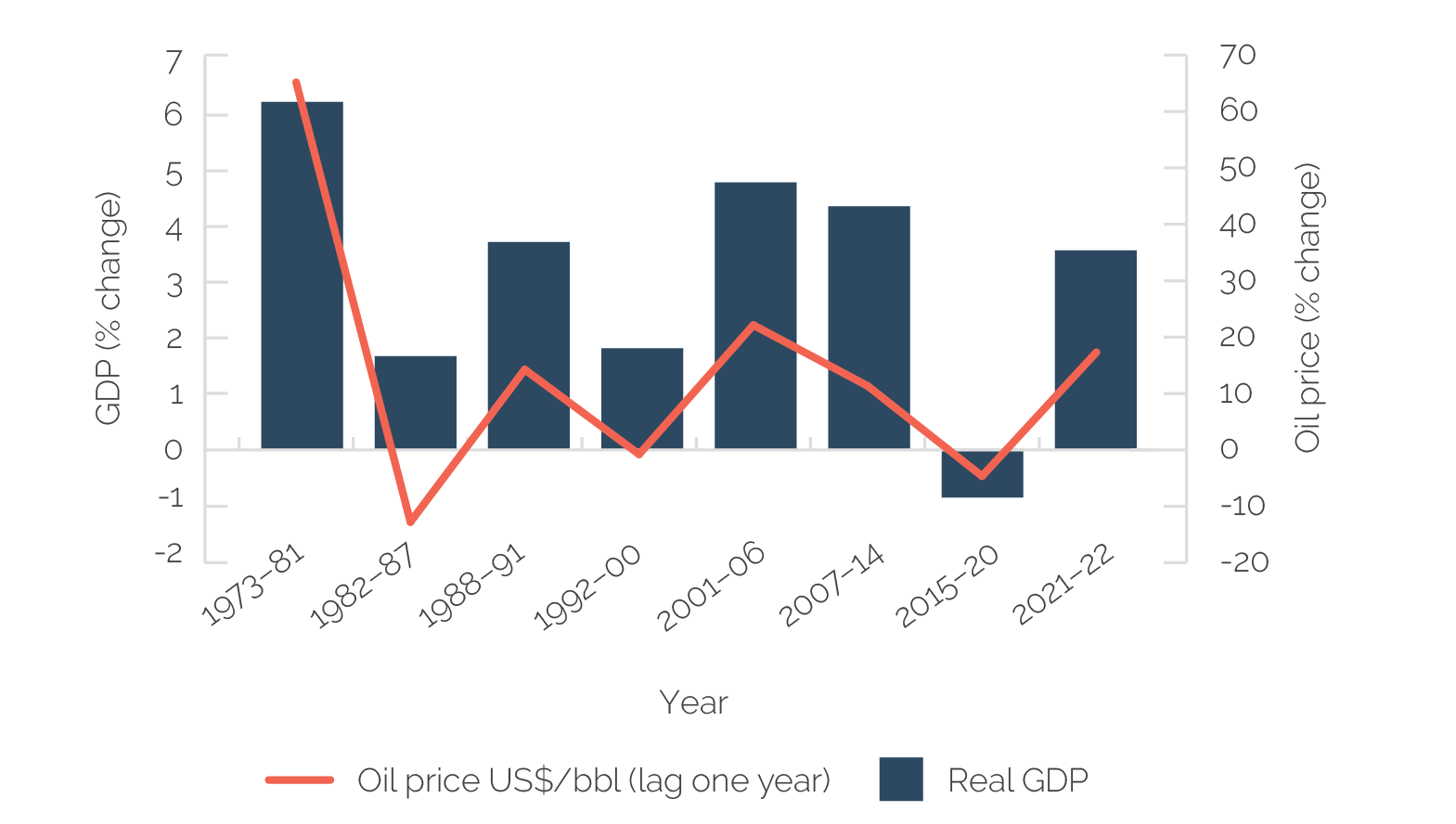

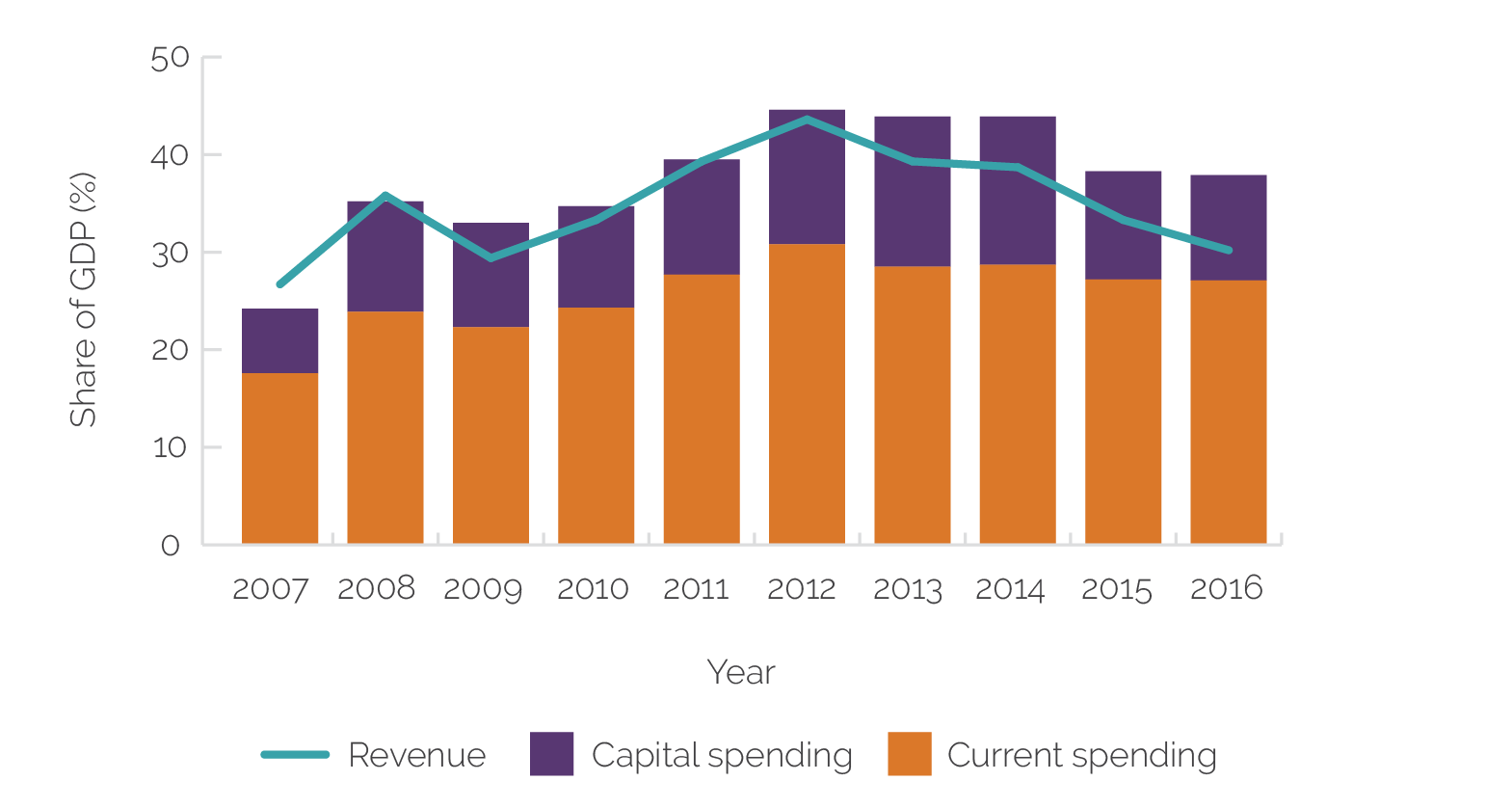

The Buen Vivir plan nearly doubled public spending, with particularly large increases in social spending. Public spending increased from nearly 24 percent of GDP in 2006 to about 46 percent of GDP in 2018, putting Ecuador at a level above that of comparator countries in the region such as Argentina at 40 percent, Bolivia at 35 percent, Colombia at 29 percent, and Peru at 19 percent (World Bank 2013). Between 2007 and 2016, spending on health doubled, whereas spending on higher education tripled from 0.7 percent of GDP to 2.1 percent, putting Ecuador at the top of Latin American countries in public spending on higher education. Spending on the government conditional cash transfer program—Bono de Desarrollo Humano (BDH)—also increased sharply from 0.49 percent of GDP in 2003 to 0.67 percent by 2013 (figure 1.3), and by 2010, 30 percent of households benefited from the program (IDB 2012).

Figure 1.3. Government Finance in Ecuador, 2007–16

Source: World Development Indicators (database), World Bank.

The Buen Vivir plan also increased infrastructure investment, targeting traditionally underresourced populations (World Bank 2018b). Public investment more than doubled from 7 percent of GDP in 2007 to 15.4 percent in 2013. The government undertook a number of large investment projects in housing, transport, energy, and water, intending to address bottlenecks and support greater inclusion in public infrastructure access. Between 2007 and 2017, the share of the population with access to safe drinking water increased from 62 percent to 66 percent, with rural households experiencing the largest gains (with the share rising from 46 percent to 51 percent). Over the same period, access to electricity became universal (rising from 97 percent to 99 percent), with electrification to rural households driving the change.3

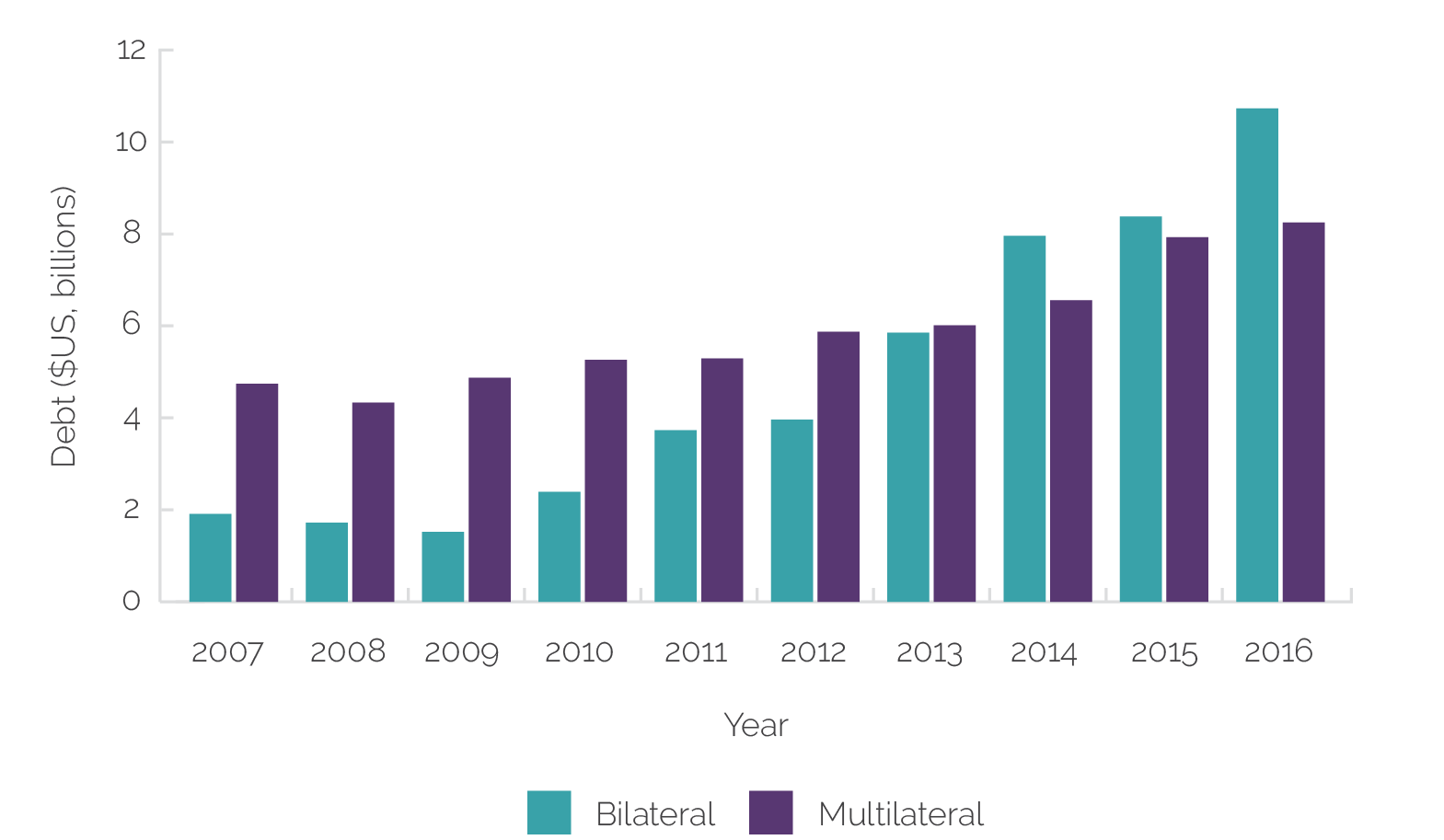

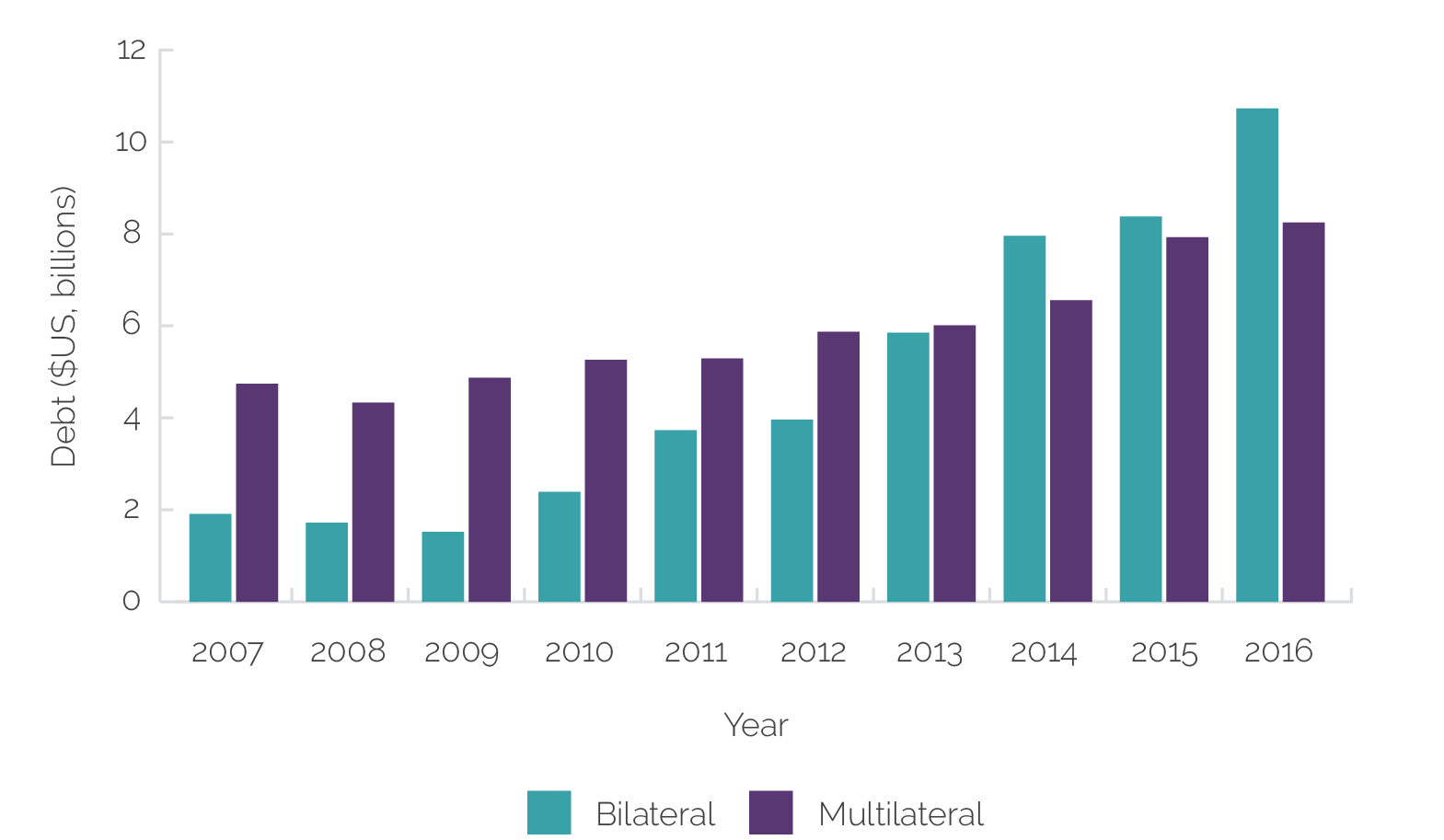

Over the early years of Buen Vivir, Ecuador realized significant public spending increases, made possible by high oil prices and borrowing from the central bank and external sources. The government agenda was supported by significantly higher oil revenues on the back of oil prices doubling between 2005 and 2011 (from $53 per barrel to $104 per barrel; they remained above $100 per barrel until mid-2014)4 and the operationalization of a new heavy crude pipeline. In addition, the government of Ecuador reduced foreign debt through a default and repurchase of sovereign bonds.5 Although dollarization reduced the ability to use monetary policy as a tool for macroeconomic management, a series of accounting practices and subsequent changes in legislation approved over the period 2009–14 allowed an expansion of the Central Bank of Ecuador’s balance sheet to finance the central government (Erraez and Reynaud 2022). Central bank borrowing to the public sector increased from 0 in 2011 to a peak of 4.4 percent of GDP in 2016 (World Bank 2019b). Over the same period, Ecuador increased its external borrowing, drawing increasingly on bilateral lenders (most importantly, China, through oil-backed loans) instead of multilateral development partners (figure 1.4). The central government also drew on nontraditional sources of finance, including short-term bonds and arrears accumulation.

Figure 1.4. Bilateral and Multilateral Debt, 2007–16

Source: Saá 2018.

Poverty and equity indicators improved markedly over the Buen Vivir plan. Aided by high oil prices, real GDP growth averaged 4.6 percent between 2007 and 2014, well above the 2.6 percent average for the Latin America and the Caribbean Region.6 With the significant boost to subsidies and government spending on social sectors, poverty and inequality declined sharply. Poverty fell from 38.3 percent to 25.8 percent between 2006 and 2014 (World Bank 2016), whereas extreme poverty was more than halved, falling from 30.9 percent in 2001 to 11.2 percent in 2012 (World Bank 2013)—the result of both stronger economic growth and government programs that targeted poor people (including the BDH cash transfer program, which doubled in size in terms of share of GDP). Ecuador’s progress on the social front put it among the best performers in the region in terms of reducing poverty (World Bank 2016).

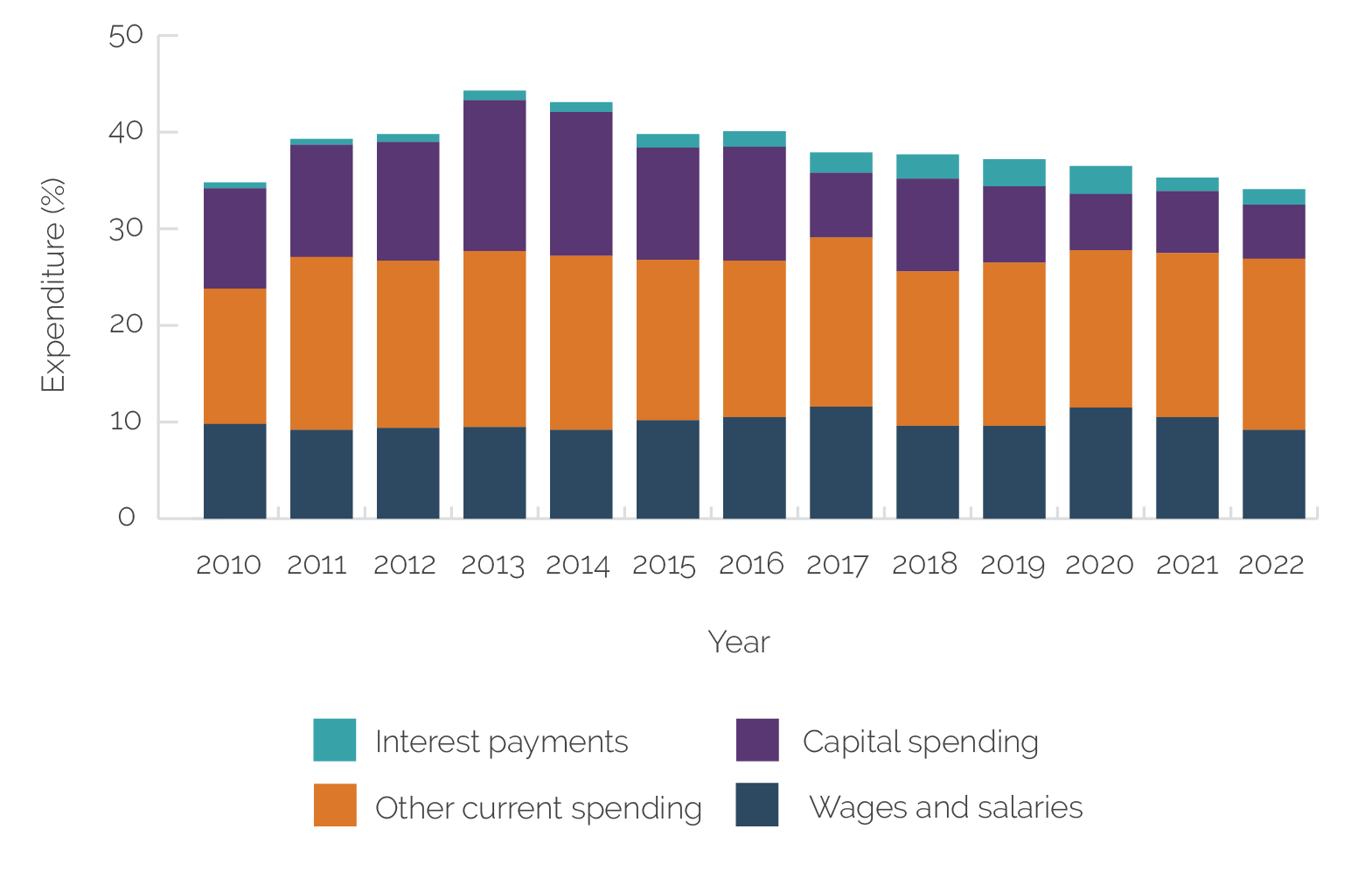

A sharp decline in oil prices starting in 2012 led to growth stagnation and growing fiscal and balance of payments pressures. Central bank financing of government spending steadily undermined the viability of the dollarization framework. This, in turn, resulted in an increase in balance of payments vulnerabilities, a high public debt-to-GDP ratio, inadequate reserve coverage, and an overvalued real exchange rate. Between 2012 and 2016, crude oil prices dropped by more than 75 percent, from an average of $113 per barrel to less than $27 per barrel (EIA 2024), resulting in a decline in oil revenues from 16.3 percent of GDP to 5.5 percent (World Bank 2019b). GDP growth stagnated in 2015 and turned negative in 2016 (contracting by 1.2 percent), and the government deficit grew, reaching 10 percent of GDP by 2016. The government of Ecuador responded by implementing tax measures and expenditure cuts, including a 25 percent reduction in public investment (figure 1.5), a temporary freeze on public sector wages, and a revision of the electricity subsidy and fuel subsidies for specific sectors.

Figure 1.5. Evolution of Public Expenditure, 2010–22

Source: Independent Evaluation Group staff estimates from World Bank and International Monetary Fund data.

Development Agenda, 2017–24

Ecuador’s new government shifted its economic policies to support macroeconomic stabilization and private sector development. Although President Lenín Moreno was elected under the auspices of his predecessor’s political movement, the new government pivoted its policy stance to stem the deteriorating fiscal and external positions and to reverse several legislative actions undertaken in the prior administration. The National Assembly passed the Productive Development Law, which reestablished the independence of the Central Bank of Ecuador, created a fiscal framework that capped the growth of public spending, set a debt anchor, and reestablished the oil stabilization fund meant to smooth spending over the commodity cycle. The government of Ecuador also adopted measures to improve public spending and tax efficiency, build fiscal buffers, and realign domestic prices and costs to address external imbalances.

The COVID-19 pandemic derailed Ecuador’s economic recovery. Oil prices dropped from almost $70 per barrel in early January 2020 to less than $30 per barrel by early April 2020. As a result, economic activity had contracted by 10 percent year on year by the second quarter of 2020, driven by large contractions in investment (−19 percent) and private consumption (−12 percent). With oil accounting for 39 percent of exports and 21 percent of fiscal revenues, Ecuador’s fiscal situation deteriorated dramatically, with the deficit for 2020 reaching 7 percent of GDP (from a 3 percent deficit in 2019). On a human scale, Ecuador was heavily hit, with over 200,000 cases and 14,000 deaths by the end of 2020. Ecuador was one of the first countries in the world to receive World Bank funds to respond to the crisis.

Reform efforts since 2021 have faced widespread social opposition. In 2021, Ecuador elected Guillermo Lasso, the first center-right president since 1996. Although President Lasso was initially praised for his handling of the COVID-19 vaccination rollout (vaccinating 9 million people within his first 100 days), there was widespread opposition to his reform agenda, which included increased taxes and changes to the calculation of the minimum wage increase. Rising food and fuel prices over 2022 led to protests in June 2022, prompting the declaration of a state of emergency in three provinces and triggering suspension of the gasoline and diesel price band system introduced in 2020. At the same time, a minimum wage increase above inflation was applied over 2022 to improve the dialogue on labor reforms.

In the context of a fragile political environment, Ecuador is mired in spiraling criminal violence. Facing an unsupportive National Assembly, President Lasso lost the constitutional referendum needed to pass legislative reforms and dissolved the legislature, which triggered early presidential and National Assembly elections in August 2023. The new president, Daniel Noboa, who will serve the remainder of Lasso’s term to 2025, confronts a rapidly deteriorating security situation in Ecuador. The highest level of violent crime in the country’s modern history was seen in 2023. Poverty (the national poverty rate stands at approximately 25 percent) and lack of job opportunities likely contribute to the recruitment of youth for criminal gangs. In the midst of a deteriorating security situation, the new government has prioritized stopping the criminal violence surge and restoring peace.

Evaluation Questions, Scope, and Methods

Background on Evaluation Questions

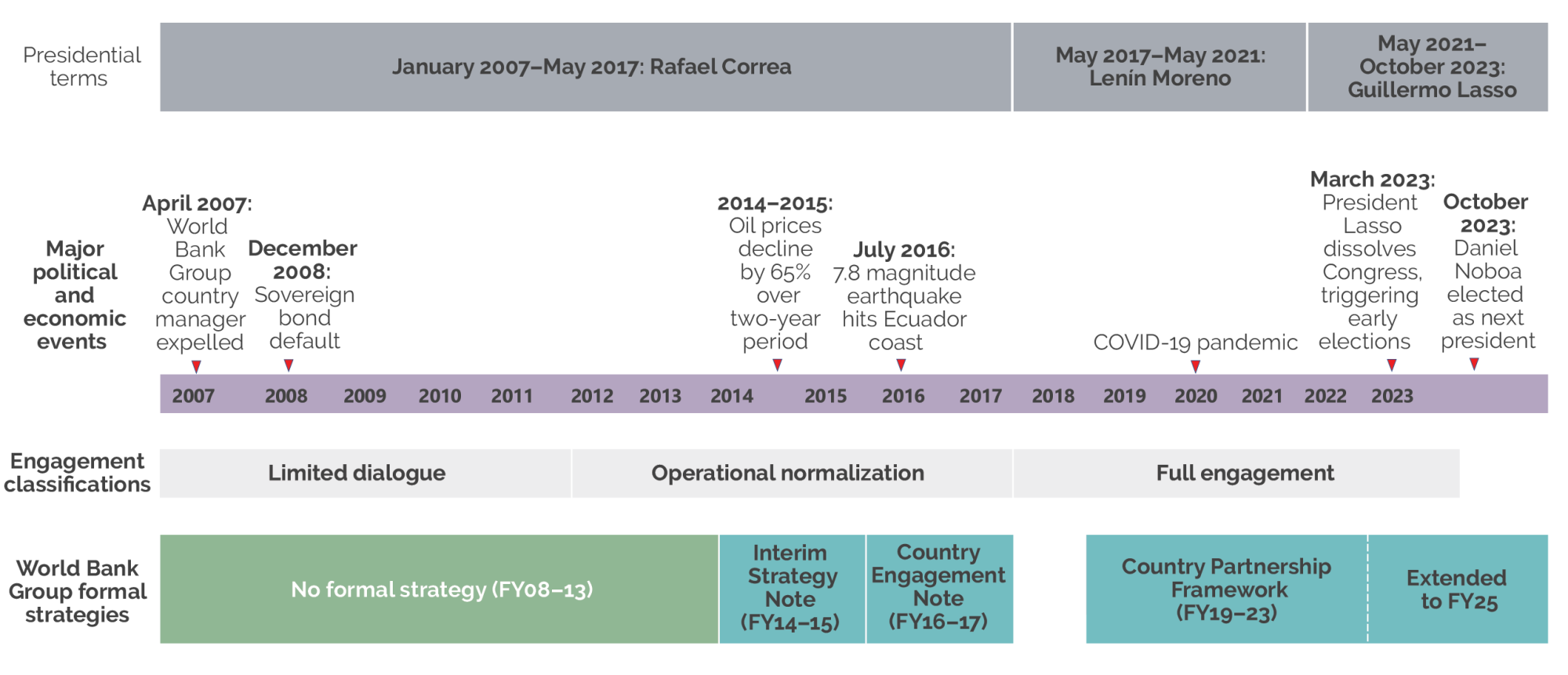

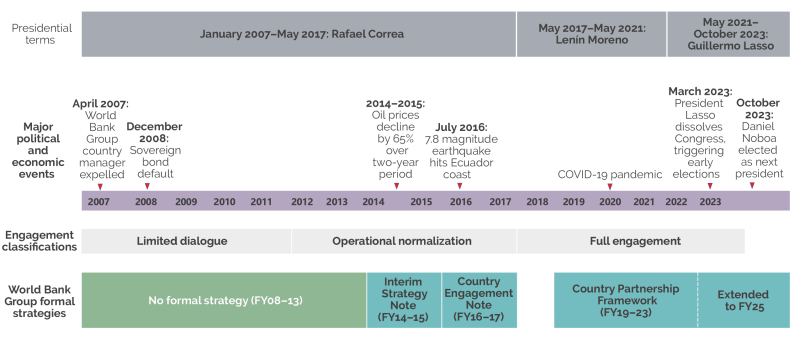

The evaluation period was a tumultuous time in which the World Bank’s engagement in Ecuador was redefined. At the start of the period, the government of Ecuador expelled the World Bank’s representative from the country and canceled all World Bank operations. The Bank Group’s support over the next 15 years can be characterized by two approaches to engagement: (i) from 2007 to 2017, the Bank Group worked to gradually reestablish a constructive partnership with the government, and (ii) from 2017 onward, the Bank Group transitioned to supporting an economic growth model that could support an expanded, dynamic, diversified, and resilient private sector. The period spans three presidential administrations (Rafael Correa 2007–17, Lenín Moreno 2017–21, and Guillermo Lasso 2021–23), three formal Bank Group strategies, and a six-year period from 2008 to 2013 without a formal strategy.

The Bank Group’s engagement from FY08 to FY22 can be broadly classified into three distinct periods:

- Limited activity (FY08–12): After a structural break between the government of Ecuador and the World Bank, the World Bank paused new activities in Ecuador for several years, only undertaking nonlending technical activities.

- Operational normalization (FY13–17): The World Bank reestablished lending operations in Ecuador by lending directly to municipalities with a guarantee from the national government. As the relationship with the government of Ecuador improved and economic conditions in Ecuador deteriorated, the World Bank broadened its lending to the national government in politically nonsensitive sectors.

- Full engagement (FY18–22): The World Bank reestablished a deep and broad dialogue and operational engagement in Ecuador, including through policy-based operations. The support is guided by a significant ramp-up in analytic work at the start of the new administration.

Evaluation Questions and Methodology

This CPE focuses on three key questions pertinent to the Bank Group’s engagement:

- Evaluation question 1 (in the context of the ruptured relationship): How effectively did the Bank Group prepare for and respond to opportunities to restore productive and broad-based engagement with the government of Ecuador?

- Evaluation question 2: How effective were the Bank Group’s preparation and support for Ecuador’s rebalancing toward a private sector–led growth model?

- Evaluation question 3: To what extent has the Bank Group contributed to ensuring that gains in social protection and inclusion were maintained and expanded, particularly in disadvantaged groups?

Evaluation question 1 examines the steps taken to strengthen the World Bank’s partnership with the government of Ecuador and assesses their relevance and effectiveness. The time frame in which this question is examined is the period 2007–17, after which (and in conjunction with a change in government administration) the World Bank resumed policy-based lending in Ecuador (representing the culmination of the rebuilding of the World Bank’s relationship with the government of Ecuador). Relevance is assessed both in terms of how the World Bank’s strategy of support to Ecuador aligned with key development priorities (as articulated in evidence-based analysis) and in terms of whether the World Bank’s strategy was pertinent to the specific objective of restoring a productive partnership with the government after the structural break. Understanding that there may be trade-offs between these distinct notions of relevance, this evaluation examines those trade-offs. The effectiveness of the Bank Group’s support is similarly examined, considering not only the Bank Group’s contributions to specific development outcomes but also whether the interventions supported the objective of restoring a productive partnership (explained further in chapter 2).

The scope of the first evaluation question covers the Bank Group’s de facto or formal country strategies and analytic and operational support over 2007–17. The Bank Group approved two formal strategies during the period: the Interim Strategy Note (ISN) for FY14–15 and the Country Engagement Note (CEN) for FY16–17. Before FY14, the World Bank had no formal strategy document for reengagement. However, major elements of the de facto strategy have been reconstructed based on information attained through document review and semistructured interviews (described in appendix A). The scope of the World Bank activities examined consists of 31 separate advisory services and analytics (ASA) initiated by the World Bank over the period (2 over the limited activity period and 29 over the operational normalization period) and 9 operations approved over the period (3 over the limited activity period and 6 over the operational normalization period). The International Finance Corporation (IFC) is not considered in the reengagement because IFC’s activities were unaffected by the World Bank’s structural break with the government of Ecuador.

Evaluation question 2 examines the Bank Group’s support for Ecuador’s transition toward a more fiscally sustainable, private sector–led growth model. The CPE assesses the Bank Group’s preparation for and implementation of support toward Ecuador’s rebalancing of its sources of economic growth. The Bank Group support is evaluated according to (i) its relevance to recognized development priorities in the context of the evolving partnership and (ii) the effectiveness of the support (examining the Bank Group’s contributions to key objectives for the transition). The key development priorities for the transition to a fiscally sustainable and private sector–led growth model correspond to the main constraints to private sector competitiveness and growth outlined in the World Bank’s Systematic Country Diagnostic (SCD) for Ecuador (FY18) and include the key conditions to address macroeconomic imbalances (primarily through fiscal and public finance reforms) and to lift the barriers to private sector development (primarily through trade, investment, and financial sector reforms and strengthening).

The scope of the second evaluation question encompasses the support of the World Bank and IFC over the full evaluation period. First, the evaluation covers World Bank analytic and operational support that focused on macroeconomic management or on the enabling conditions for the private sector. With regard to the enabling environment for the private sector, the evaluation limits its coverage to support toward the policy environment (through trade and business regulatory and labor market reforms) but not activities addressing the physical conditions of the enabling environment (such as infrastructure, information and communication technology, and transport). Second, the evaluation covers IFC advisory services toward business regulatory reform. Third, the evaluation covers both World Bank and IFC support toward improving firms’ access to finance (with World Bank support primarily toward financial sector reforms and with IFC support primarily toward investments in the banking sector). Finally, the evaluation covers IFC investments in the agribusiness sector. The list of examined World Bank support activities includes (i) 5 World Bank–financed operations (the First, Second, and Third Inclusive and Sustainable Growth development policy operations [DPOs], FY19, FY20, and FY21, respectively; Promoting Access to Finance for Productive Purposes for Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises [MSMEs] investment project financing [IPF], FY21; and the First Green and Resilient Recovery DPO, FY22, with a follow-up operation not included in the evaluation period); (ii) 25 World Bank analytic and advisory activities; (iii) 7 advisory services undertaken by IFC in Ecuador and 6 regional Latin America and the Caribbean advisory services that benefited clients in Ecuador; (iv) 18 IFC investments in the banking sector; and (v) 16 IFC investments in the agribusiness sector.

Evaluation question 3 assesses the World Bank’s support for social protection and inclusion. The World Bank’s support is evaluated based on (i) its relevance to the recognized development priorities of maintenance and expansion of social protection and inclusion, in the context of the evolving relationship, and (ii) its effectiveness in maintaining and expanding achievements in social protection and inclusion.

The scope of the third evaluation question covers the Bank Group’s social protection support over the full evaluation period. In total, the support included 25 pieces of analytic work and 2 operations (1 with additional financing).

The CPE draws on several information sources. The main documentation drawn on is as follows: (i) World Bank portfolio documentation over the period, including outputs of ASA, Project Appraisal Documents, Implementation Completion and Results Reports, Implementation Completion and Results Report Reviews, Implementation Status and Results Reports, Restructuring Documents, Project Completion Reports, aide-mémoire, review of meeting minutes, and project-related communication; (ii) IFC portfolio documentation, including Board approval documents, supervision reports, Expanded Project Supervision Report (XPSR) Evaluative Notes, and Evaluative Notes of IFC advisory services; (iii) internal and external diagnostic analytic work; (iv) formal Bank Group strategies (figure 1.6), including the ISN for FY14–15, the CEN for FY16–17, the Country Partnership Framework (CPF) for FY19–23, and the Performance and Learning Review for FY19–23, as well as the strategies of external development partners, including the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) and Banco de Desarrollo de América Latina y el Caribe (CAF; formerly Corporación Andina de Fomento); and (v) media content. Independent Evaluation Group (IEG) staff supplemented these sources with information from interviews conducted during the CPE preparation. IEG undertook structured interviews with more than 100 Bank Group staff who worked on the Ecuador country program over the evaluation period, including three vice presidents, four country directors, and five country managers. In addition, IEG undertook a mission to Ecuador in February 2023, during which it interviewed more than 75 government counterparts involved with World Bank–supported projects or IFC investments. IEG also interviewed development partners heavily involved in supporting the government of Ecuador over the period.

The evaluation draws primarily on qualitative data and validates findings through data triangulation. Data analysis methods included portfolio review and analysis, content analysis of existing evaluations, review of internal and external analytic work, analysis of structured interview responses, media analysis, and theory-based evaluation techniques. Drawing on a range of deliberative evidence, including minutes from review meetings, project documentation, and structured interview responses, the team reconstructed the theories of change that guided the World Bank’s decisions over the reengagement period, supplemented with contribution analysis to confirm and revise these theories. Appendix A describes the specific methods and information sources used for each evaluation question.

Figure 1.6. Timeline of Major Political and Economic Events in Ecuador, 2007–23

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: FY = fiscal year.

- Excluding high-income countries.

- According to an International Monetary Fund working paper that analyzed the causes of the crisis (Jácome 2004), institutional weaknesses restricted the government’s ability to respond to the crisis in a timely manner, public finance rigidities limited the government’s capacity to correct emerging imbalances, and financial dollarization fostered foreign currency demand and accelerated a currency crisis, thereby further worsening the solvency of banks.

- World Development Indicators (database), World Bank; between 2007 and 2017, rural electrification rose from 92 percent to 98 percent.

- Average crude oil price per barrel (Brent, Dubai, and West Texas Intermediate average; World Bank Commodity Price Data, World Bank Prospects Group).

- The government of Ecuador defaulted on two sovereign global bond issues totaling $3.2 billion in December 2008 (about one-third of Ecuador’s external debt), which were subsequently repurchased by the government at a discount.

- World Development Indicators (database), World Bank.