Transitioning to a Circular Economy

Chapter 1 | Background and Context

Highlights

This evaluation assesses how well the World Bank Group has supported client countries with managing municipal solid waste to advance their development and sustainability goals. The evaluation covers World Bank, International Finance Corporation, and Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency activities that supported municipal solid waste management (MSWM) in fiscal years 2010–20.

Municipal solid waste—waste generated from residential and commercial sources and managed mainly by local governments—is projected to triple in volume in low-income countries (and nearly double in lower-middle-income countries and upper-middle-income countries) by 2050. Most of the waste in low-income countries and lower-middle-income countries is managed improperly, untreated, and disposed of in open dumps.

The growing volume and changing composition of waste (including nonbiodegradable and plastic waste), if left unmanaged, will continue to contribute to greenhouse gas emissions and global and local land and water pollution that affect the health and welfare of impoverished people disproportionately.

It is widely accepted that municipal solid waste should be managed through a waste hierarchy approach that seeks to reduce consumption and increase reuse to complement efforts focused on waste collection, recovery, and disposal. The waste hierarchy is complemented by a wider circular economy approach that advocates for designing products to reduce waste, using products and materials for as long as possible, and recycling end-of-life products back into the economy.

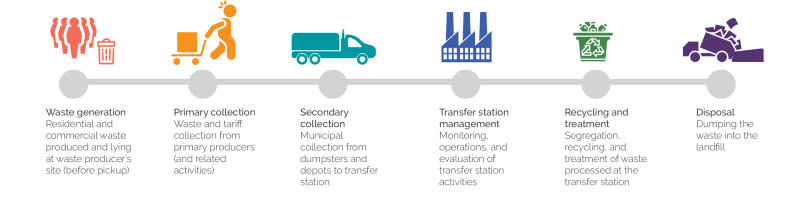

The Bank Group delivers MSWM support to its clients across two pillars that are an organizing framework for this evaluation: policies and institutions, and infrastructure, access, and service delivery. This evaluation also considers how the Bank Group articulates and captures the environmental, social, health, and economic outcomes that are expected to come from improved MSWM.

Municipal solid waste is one of the most pressing challenges worldwide. Global municipal solid waste is increasing rapidly; currently, the world’s cities produce about 1.3 billion tons of waste annually, expected to rise to 2.2 billion tons annually by 2025 (Hoornweg and Bhada-Tata 2012). Historically, the causes and effects of municipal solid waste were considered local or regional; however, with increasing volumes and changing waste compositions, municipal solid waste has become a global challenge with growing public health, environmental, social, and economic costs.

Definition and Dimensions

Municipal solid waste is waste generated mainly from residential and commercial sources and managed mostly by local governments. Municipal solid waste is defined as waste collected and treated by or for municipalities. It covers waste from households, including bulky waste; similar waste from commerce and trade, office buildings, institutions, and small businesses; yard and garden waste; street sweepings; the contents of litter containers; and market waste if managed as household waste. The definition excludes waste from municipal sewerage networks and treatment, as well as waste from construction and demolition activities.1

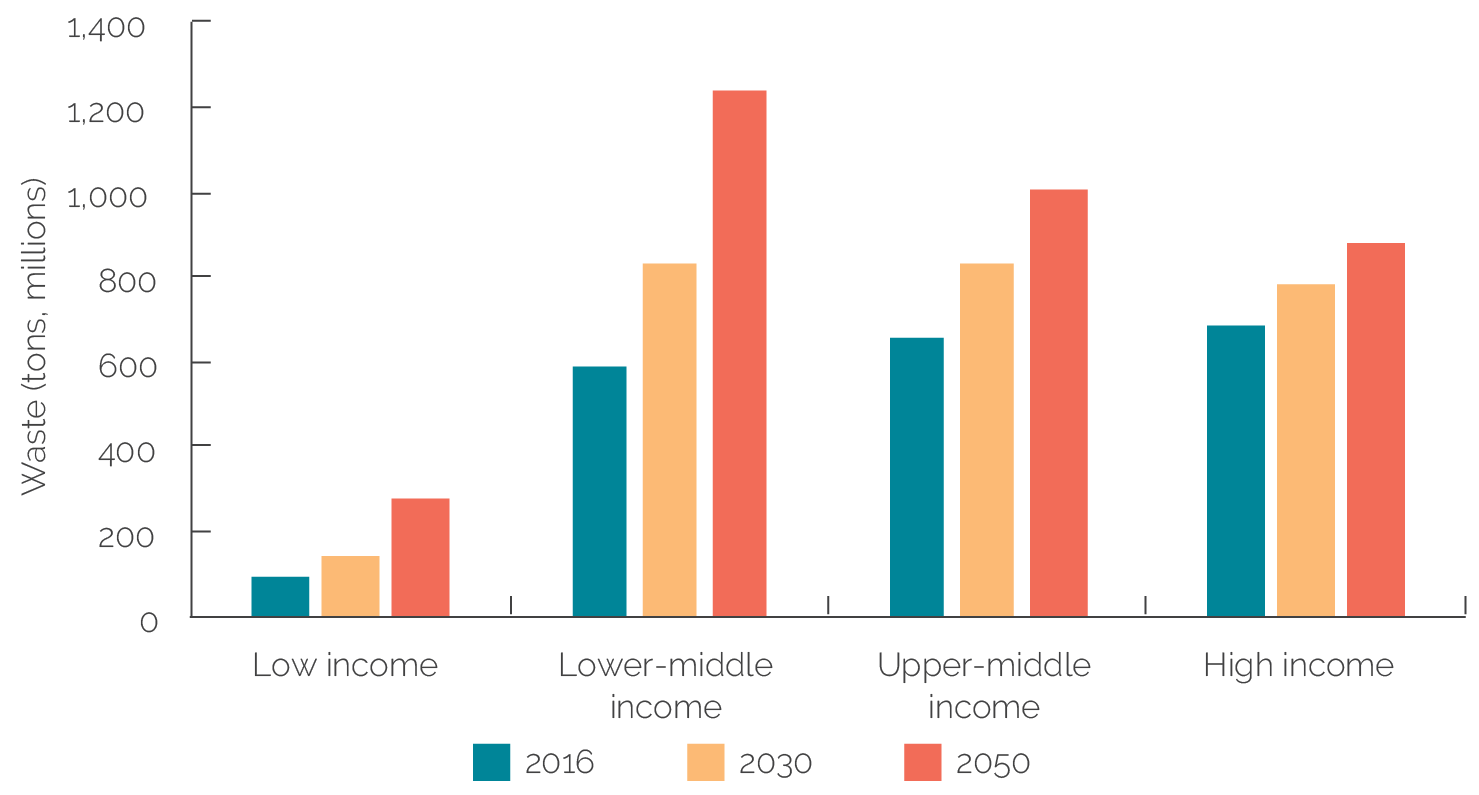

Municipal solid waste management (MSWM) consists of six stages: generation, primary collection, secondary collection, transfer station management, recycling and treatment, and disposal. Typically, waste generated by residential and commercial entities undergoes primary collection at the source. It is then conveyed through secondary collection to a transfer station, where it is segregated and composted, recycled, or treated before the remaining waste is disposed of in a controlled landfill. The treatment or recovery can be through converting waste to energy using biological or thermal treatment, including incinerators (figure 1.1).2

Figure 1.1. Municipal Solid Waste Management Process: Typical Stages

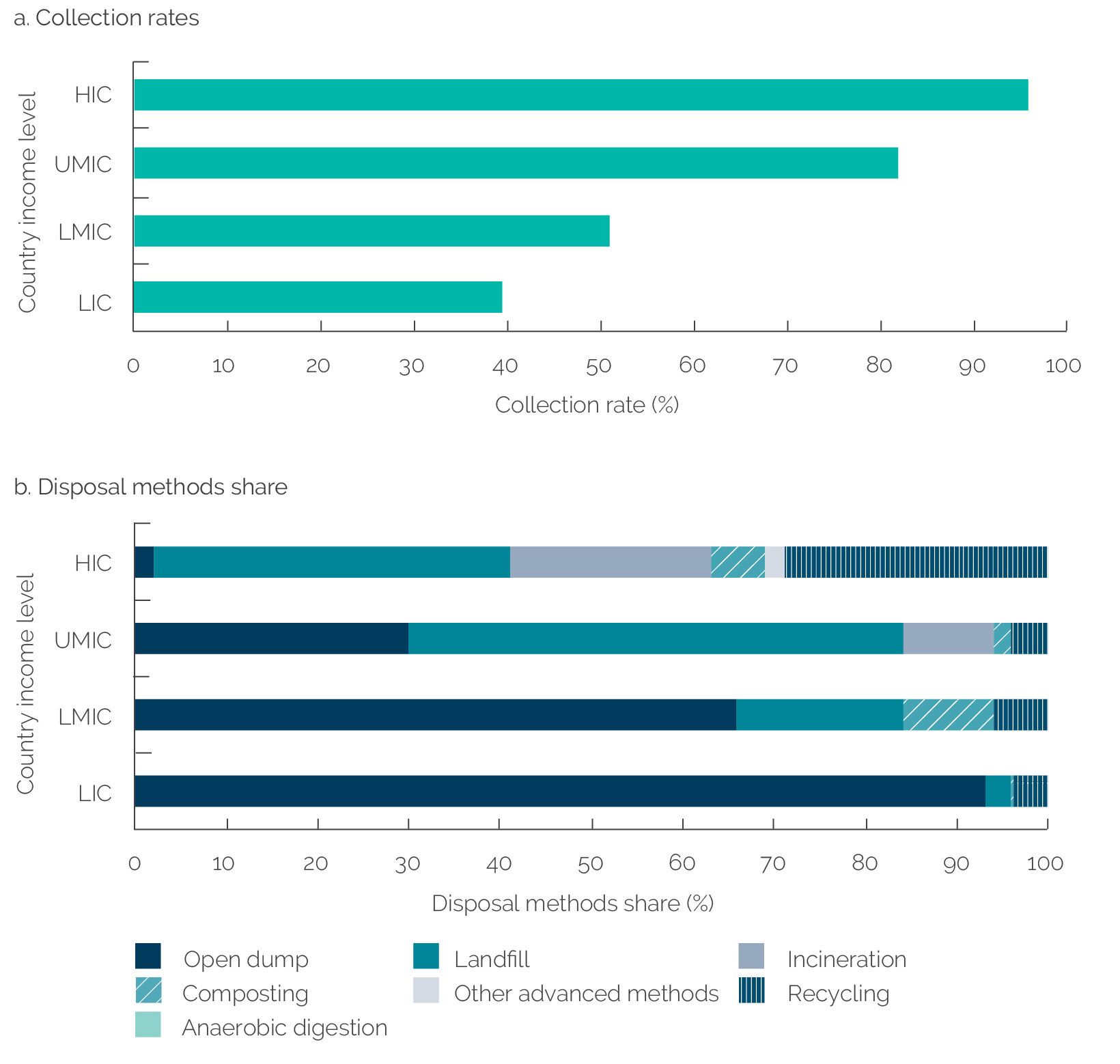

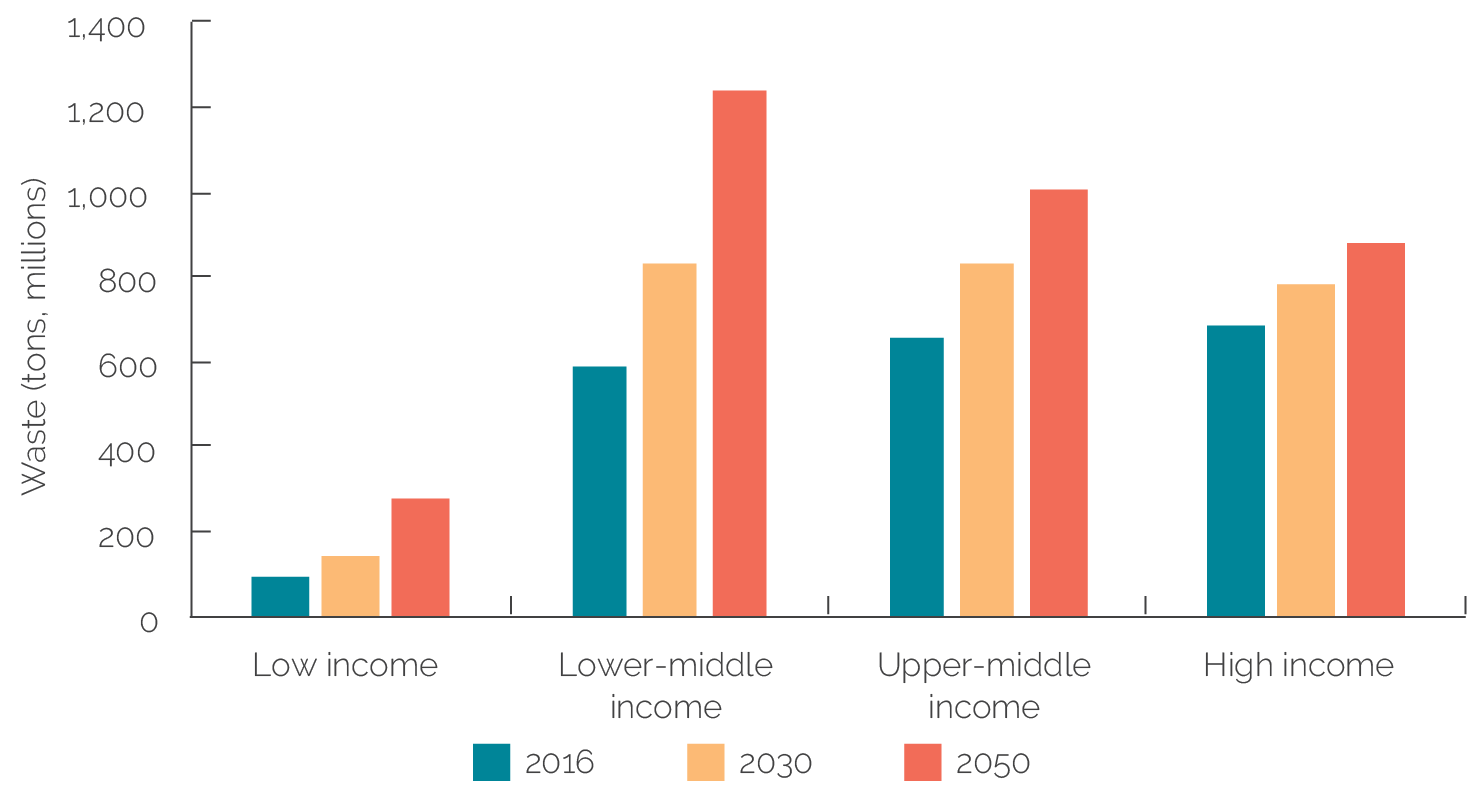

The volume of municipal solid waste is growing fastest in low-income countries (LICs). As of 2020, high-income countries (HICs) and upper-middle-income countries (UMICs) together generate 71 percent of all municipal solid waste (Kaza, Shrikanth, and Chaudhary 2021). The average quantity of municipal solid waste generation per person per day is about 1.6 kilograms in HICs, 0.91 kilograms in UMICs, 0.47 kilograms in lower-middle-income countries (LMICs), and less than 0.41 kilograms in LICs. Fast-growing large- and medium-size cities will nearly double the waste generation in LMICs and UMICs by 2050 (figure 1.2). LICs will see even faster growth, with annual waste generation tripling from 93 million tons to 283 million tons over the same period. By contrast, the corresponding growth will be less than 30 percent in HICs.

Figure 1.2. Estimated Waste Generation by Country Income Classification

Source: Adapted from Kaza et al. 2018.

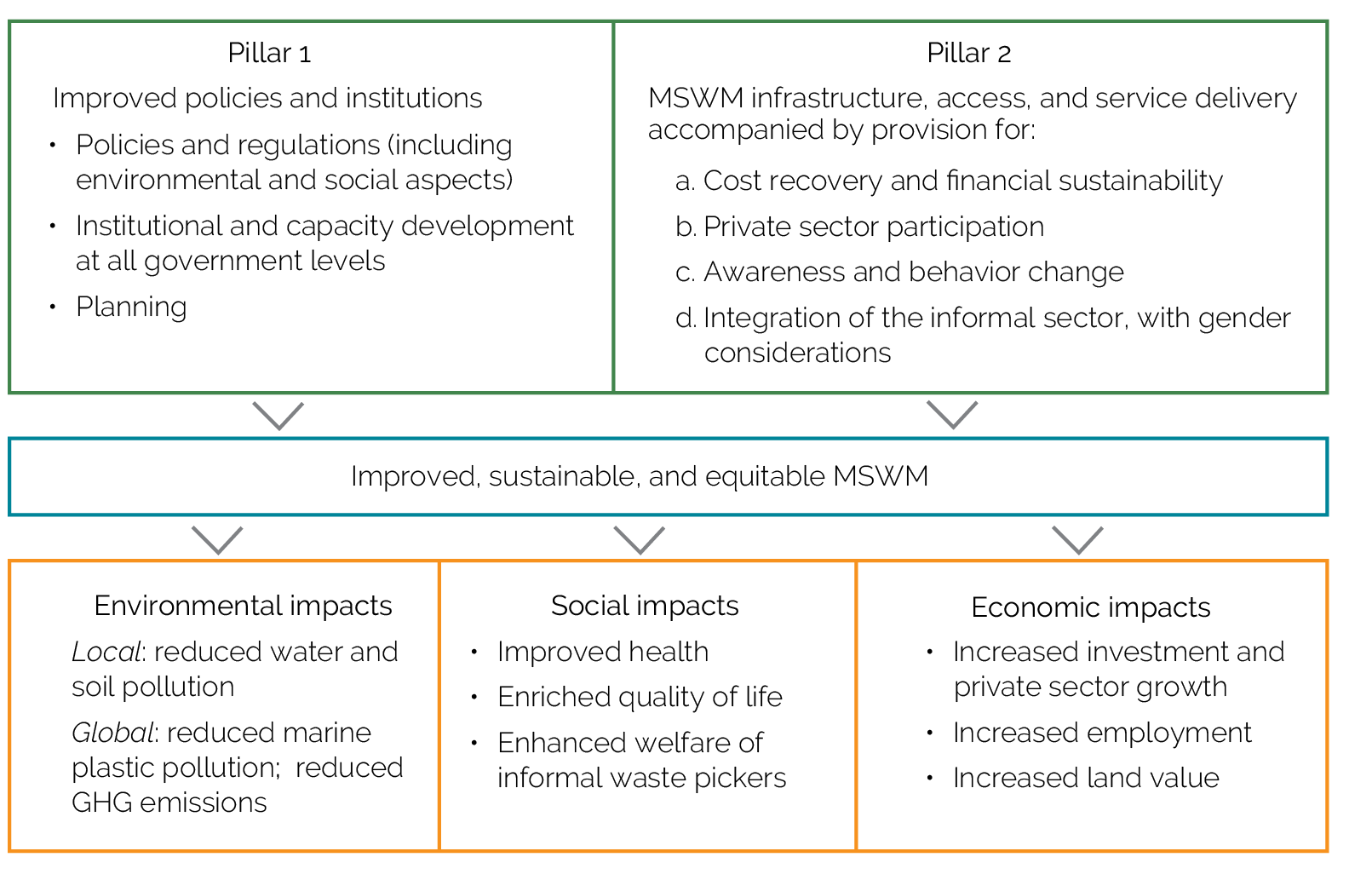

LICs and LMICs have greater challenges than UMICs and HICs in managing municipal solid waste. Collection rates correlate with country income. LICs collect only 39 percent (by weight) of the municipal waste they generate; LMICs collect 51 percent, UMICs collect 82 percent, and HICs collect 96 percent (figure 1.3, panel a). The use of proper disposal methods also varies by country income. The collected waste ends up predominantly in open dumps in LICs (93 percent) and LMICs (66 percent); this share is progressively less in UMICs (30 percent) and HICs (2 percent). LICs and LMICs have few sanitary landfills or recycling facilities and no incineration facilities (Kaza et al. 2018; figure 1.3, panel b).

Figure 1.3. Select Municipal Solid Waste Parameters by Country Income Category

Source: Adapted from Kaza et al. 2018.

Note: HIC = high-income country; LIC = low-income country; LMIC = lower-middle-income country; UMIC = upper-middle-income country.

Several actors have roles to play in MSWM. Residential and commercial entities are the sources of municipal solid waste and the beneficiaries of municipal solid waste services. Local governments are the principal sources of municipal solid waste financing and service provision, but central and regional governments perform policy setting and regulatory functions and provide supplementary financial support. Civil society and nongovernmental organizations raise awareness for MSWM, hold service providers accountable, and support the informal waste picker community, which plays an important role in collecting and reclaiming recyclable and reusable material. The private sector is a potential source of investment, higher efficiency in service delivery, and improved practices, including extended producer responsibility, whereby manufacturers are physically and financially responsible for the disposal of their products. The informal sector (informal waste pickers) operates where formal services are inadequate.

Inadequate MSWM causes harmful local and global impacts through air, land, and water contamination. At the local level, inadequate MSWM has a significant bearing on overall quality of life through environmental, social, and economic impacts that affect impoverished people disproportionately. Globally, it contributes to climate change and growing plastic pollution.

- Weak MSWM at the local level affects health and quality of life adversely. Improper waste management and open dumping and burning of municipal solid waste—which are more common in LICs and LMICs—pollute soil, air, and water and attract disease vectors. Mismanaged waste can clog stormwater drains, resulting in flooding that creates unsanitary and toxic conditions, disproportionately affecting impoverished people, who are likely to live near or work at waste disposal locations (Giusti 2009). When waste is burned, the resulting toxins and particulate matter in the air can cause respiratory and neurological diseases, among other health issues (Thompson 2014).

- Weak MSWM also contributes to climate change. Landfills and open dumps contribute about 4 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions, though waste can potentially be a resource and a net sink of greenhouse gases through recycling and reuse (Barrera and Hooda 2016).

- Marine and riverine plastic pollution have particularly serious consequences for ecosystems and the health and livelihoods of people living near the water. Damage caused by plastics to the marine environment is estimated at $13 billion per year and upward of $75 billion when considering the total natural capital cost of plastics used in consumer goods (World Bank Group 2021). In a business-as-usual scenario, the global flow of plastics to the oceans will nearly double between 2015 and 2025. About 80 percent of ocean plastic originates from land, and 75 percent of that comes from poorly operating MSWM systems (Fletcher 2021).

- The millions of informal waste pickers worldwide who make a living by collecting, recycling, and selling reusable waste face low social status, work and live in deplorable conditions, and get little support from local governments. An estimated 24 million waste pickers are in the informal sector worldwide, mostly in developing countries but also in richer countries (ILO 2013). Informal waste pickers provide widespread public benefits by recovering a greater proportion of recyclables than the formal sector in most LICs and LMICs, but they work under difficult conditions and with low returns. Women and children are significant participants in the informal sector and are especially vulnerable regarding their safety and welfare (Dias 2021).

Multilateral development institutions and private investment pay substantially less attention to MSWM than to other urban services. An assessment by the International Solid Waste Association found that, between 2003 and 2012, the share of solid waste management in all official development finance was only 0.32 percent (Lerpiniere et al. 2014). Recent donor assistance for MSWM (from the Asian Development Bank, the African Development Bank, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, and the Inter-American Development Bank) varied between 0.5 and 6.1 percent of all urban sector commitments during 2010–20. The Public-Private Infrastructure Advisory Facility database shows that in 2020, MSWM received $1 billion in private investments, compared with $4 billion for water supply and sanitation. All the private investment in MSWM was directed toward UMICs.

The municipal solid waste sector lacks an international mechanism to promote a coordinated approach. There is no global coordination mechanism devoted to solid waste management, unlike in other urban sectors (such as water supply, sanitation, transport, and energy). The only such mechanism focusing on waste management, the Global Partnership on Waste Management, was launched in 2010 but stopped functioning in 2019 without conducting any significant activities.3

Current and Emerging Approaches

MSWM is at the core of (i) Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 11 for sustainable cities and SDG 12 for reducing waste (and is relevant to issues addressed by other SDGs) and (ii) efforts to achieve green, resilient, and inclusive development. SDG 11 for sustainable cities addresses it directly by targeting service delivery for waste management, and SDG 12 for reducing waste generation addresses it through prevention, reduction, recycling, and reuse, which are essentially the elements of the waste hierarchy approach to MSWM described in the next paragraph. Other SDGs address means of converting selected waste to energy, the welfare of informal waste pickers, the role of MSWM in climate action, and marine plastic pollution (appendix A).

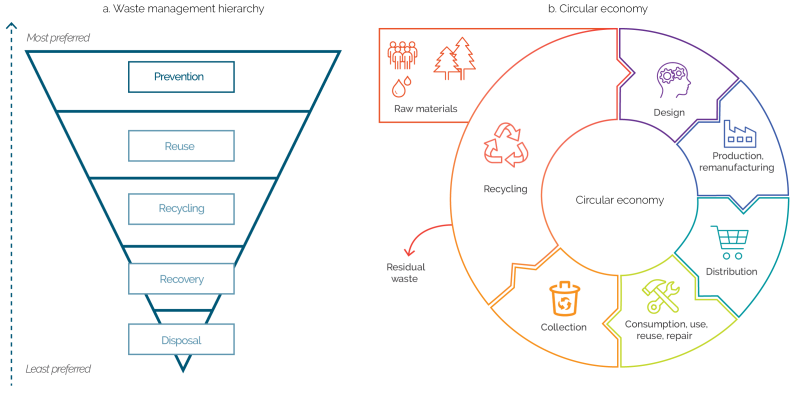

The waste hierarchy is a widely accepted principle for managing waste efficiently and sustainably. The waste hierarchy is typically presented as an inverted pyramid that shows approaches to MSWM from most to least preferred (figure 1.4, panel a). In this formulation, minimizing consumption and improving source reduction, along with increasing reuse, are preferable to recycling, which is preferred to recovery (for example, waste to energy, composting, and incineration) before disposing the remaining waste in an environmentally responsible manner, typically in sanitary landfills. Countries vary widely in how much they have transitioned from less to more desirable approaches in the waste hierarchy.

The broader circular economy approach is a sustainable alternative to the traditional linear (take-make-dispose) economic model. The circular economy approach advocates for designing products to reduce waste, using products and materials for as long as possible, and recycling end-of-life products back into the economy (figure 1.4, panel b). In the transition to a circular economy, it is important for consumers to demand extended producer responsibility, whereby manufacturers are physically and financially responsible for the disposal of their products.4 According to the independent Circularity Gap Report 2021, the global economy is only 8.6 percent circular, wasting 91.4 percent of everything that is used (Circle Economy 2021). Application of the circular economy principle to MSWM is gaining traction in HICs, and awareness and interest is increasing in LICs, LMICs, and UMICs.

Figure 1.4. The Waste Hierarchy and the Circular Economy

Sources: Panel a: UNEP 2011; panel b: European Parliament 2021.

Evaluation Scope and Organizing Framework

The evaluation covers World Bank, International Finance Corporation (IFC), and Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA) activities that supported MSWM during fiscal years (FY)10–20. It covers World Bank projects and advisory services and analytics (ASA), IFC investments and advisory services, and MIGA guarantees.

The World Bank Group delivers MSWM support to its clients across two pillars that are an organizing framework for this evaluation: policies and institutions, and infrastructure, access, and service delivery. The first pillar covers the interlinked areas of policies, institutions, capacity, and planning at the central, provincial, and local government levels. The second pillar covers improved and sustainable access and service delivery through enhanced infrastructure and processes that promote accountability for service delivery, financial sustainability, and awareness and behavior change.

Integrated support for the two pillars is expected to lead to improved, sustainable, and equitable MSWM that will result in positive local and global environmental, social, and economic impacts. Global environmental impacts include reduced greenhouse gas emissions and marine plastic pollution. Local environmental impacts include reduced soil and water contamination and improved air quality, which would also enhance health. Social impacts include improving the welfare and livelihood security of informal waste pickers. Economic impacts come from job creation in the sector and the secondary effects that improved MSWM can have on land value and the expansion of economic activity in general (for example, in tourism) (figure 1.5).

Figure 1.5. Evaluation Framework for Improved Municipal Solid Waste Management

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: GHG = greenhouse gas; MSWM = municipal solid waste management.

Evaluation Aim, Questions, and Methods

This evaluation is the first major Independent Evaluation Group (IEG) study of the Bank Group’s support for MSWM. The evaluation builds on and contributes to IEG’s work stream on climate change and environmental sustainability.

This evaluation aims to assess how well the Bank Group has supported client countries to manage solid waste to advance goals related to development and sustainability, including climate-related goals. The three main evaluation questions are as follows:

- How relevant is the Bank Group’s approach and engagement in meeting client country needs, considering the latest evidence and thinking on MSWM practices and country context and readiness?

- How effective have Bank Group engagements been in delivering improved MSWM for clients?

- How coherent has Bank Group engagement been in collaboration among the World Bank, IFC, and MIGA, and collaboration and partnerships with other actors to support better outcomes for client needs in MSWM?

The evaluation uses a mixed methods approach based on consultative theory- and case-based principles. The evaluation team consulted with staff across World Bank Global Practices and IFC industry departments and conducted a targeted literature review, a review of Bank Group country strategies, a Bank Group portfolio review, two project performance assessments, and seven country case studies. IEG conducted the case studies through virtual discussions with World Bank staff and stakeholders for six economies (Azerbaijan, Colombia, Kenya, Morocco, Nigeria, and West Bank and Gaza) and through desk-based research for Liberia. Coronavirus pandemic–related travel restrictions made virtual discussions necessary (appendix C).

- As defined in https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/environment/municipal-waste/indicator/english_89d5679a-en

- Waste to energy is a very broad term that encompasses several technology options, from low-temperature landfill gas recovery through medium-temperature anaerobic (bio) digestion, to high-temperature thermal treatment (incineration, gasification, pyrolysis). The application of high-temperature thermal treatment facilities in most client countries should be considered carefully in terms of costs of technology and operation, potential for environmental risks if not operated correctly, maintenance and repair, capability to operate, and public perception.

- The Global Partnership on Waste Management was launched in 2010 to enhance international cooperation, outreach, advocacy, and knowledge management and sharing and to raise awareness and political will for waste management. It was a partnership of four international agencies, but multilateral development banks and international agencies covering urban issues were not represented. It was closed in December 2019, and there have been no activities since then. The partnership’s website has no mention of activities between 2010 and 2019.