Making Waves

Chapter 2 | The World Bank’s Articulation of the Blue Economy

Highlights

As a knowledge broker, the World Bank lifted a progressive blue economy concept onto the world stage, heightening its credibility through blue economy–focused analytics, often financed by bilateral partners. These analytics focused on the potential of the blue economy to achieve balanced economic, environmental, and social development aims in coastal and marine areas.

However, the World Bank’s corporate definition of the blue economy falls short of articulating key tenets of the blue economy as expressed in its own analytics and that of key partners. The World Bank’s corporate definition refers to resource preservation, rather than restorative goals; lacks references to inclusion and equity; does not refer to integrated approaches; and appears decoupled from pressing food and nutrition security, climate change, biodiversity, and circular economy goals.

Clearly articulating the holistic purpose of the blue economy is important because clients are using the World Bank’s corporate definition to inform their blue economy strategies, and key partners rely on the World Bank to communicate the more holistic aim in their dialogue with clients. With some exceptions, there is low understanding among World Bank staff of the more holistic meaning of the blue economy.

The blue economy is being referenced in many small island developing states country diagnostics (that is, Systematic Country Diagnostics and Country Climate and Development Reports) and it is slowly emerging in those for coastal states, but the comprehensiveness of the concept is low overall. Apart from those for small island developing states, the blue economy concept is not being referenced in Country Economic Memorandums.

Whereas focused blue economy analytics have been critical for integrating the blue economy concept in country diagnostics, sector analytic work (for example, on fisheries, waste management, or pollution) has not sufficiently reflected blue economy considerations.

This chapter focuses on how well the World Bank is articulating blue economy aims, including in relation to other actors, at the corporate and country levels. To assess how well the World Bank is articulating blue economy aims at the corporate level, we used content analysis to determine the presence, meaning, and evolution of the blue economy concept as expressed in focused World Bank–published blue economy analytic products. To evaluate how well the World Bank is articulating blue economy aims at the corporate level in relation to other actors, we used content analysis to assess how the blue economy concept is articulated in key partner strategies and publications. We then complemented these analyses of partner publications by conducting 24 global blue economy expert interviews. These interviews were conducted with representatives of other agencies and organizations, including PROBLUE donors (Canada, France, Germany, Iceland, Ireland, Norway, and Sweden), the United Nations Development Programme, the United Nations Environment Programme Sustainable Blue Economy Initiative, the United Nations Environment Programme Finance Initiative, the Commonwealth Secretariat, the Global Environment Facility, the World Wide Fund for Nature (previously the World Wildlife Fund), the International Coral Reef Initiative, the Ocean Risk and Resilience Action Alliance, and the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services as well as individual global experts who are helping shape global and country blue economy policies (anonymized information on interviewee selection—ensuring representative viewpoints—is included in appendix A). To assess how well the World Bank is articulating blue economy aims at the country level, we used content analyses, coding templates, and scoring rubrics to determine the presence and comprehensiveness of the blue economy concept in all 84 SCDs, 46 CEMs, and 23 CCDRs for countries in scope. These diagnostics were chosen because they serve as reference points for client consultations and are used to set priorities for World Bank Group country engagements (World Bank 2016c; see appendix A for coding templates for each diagnostic; the data package for the coded qualitative data is available on request).

Corporate Articulation of the Blue Economy

As a knowledge broker, the World Bank lifted a progressive blue economy concept onto the world stage, heightening its credibility through analytics. Beginning in 2016, the World Bank helped lift the blue economy concept out of country conferences into a series of client-facing, focused analytics that enhanced the concept’s credibility and reach. This effect was confirmed by interviews with clients and donor partners. By explicating the concept in its earliest analytic, Toward a Blue Economy: A Promise for Sustainable Growth in the Caribbean (Patil et al. 2016), the World Bank helped lift the concept out of the Eastern Caribbean onto the global stage, including by presenting the concept, together with Caribbean leaders, at the 27th Conference of the Parties.1 These blue economy analytics included clear purpose statements and explanations about the potential of the blue economy to achieve balanced economic, environmental, and social development objectives in ocean and coastal areas. The report stated that the blue economy is “a lens by which to view and develop policy agendas that simultaneously enhance ocean health and economic growth, in a manner consistent with principles of social equity and inclusion” (Patil et al. 2016, 43). Pursuant to its support in the Eastern Caribbean, the World Bank transferred this knowledge to South Asia (Bangladesh) through analytics co-produced with the European Union. The Bangladesh analytic (the second of its kind) refers to the blue economy as “a sustainable ocean economy, in which economic wealth is balanced with the health of ocean ecosystems and their natural assets, and is socially sustainable” (Patil et al. 2018, 5). The World Bank also acted globally to facilitate a common understanding of the blue economy concept. By partnering with the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, the World Bank convened a multistakeholder event and copublished the seminal report on the topic, titled The Potential of the Blue Economy: Increasing Long-Term Benefits of the Sustainable Use of Marine Resources for Small Island Developing States and Coastal Least Developed Countries (World Bank and UN DESA 2017). This effort produced a common understanding that the blue economy must prioritize ocean health; it also established parameters for blue economy investments that must (i) provide social and economic benefits for current and future generations; (ii) restore, protect, and maintain the diversity, productivity, resilience, core functions, and intrinsic value of marine ecosystems; and (iii) be based on clean technologies, renewable energy, and circular material flows that reduce waste and promote recycling.

However, the World Bank’s corporate definition of the blue economy falls short of articulating key tenets of the blue economy as expressed in its analytics. As indicated in chapter 1, the corporate definition for the blue economy put forth by the World Bank in 2017 is “the sustainable use of ocean resources for economic growth, improved livelihoods, and job creation while preserving the health of ocean ecosystems” (World Bank 2017e). This definition leaves out core tenets of the blue economy concept that are more clearly and comprehensively articulated in the abovementioned analytics. Although the World Bank’s corporate definition references three pillars (growth, livelihoods, and ocean health), the focus on economic growth while preserving the health of the ocean implies that the oceans are in a state of existing good health. The definition lacks references to the restorative potential of the blue economy, including efforts to regenerate, restore, and conserve resources, which also deliberately tackle the drivers of degradation. The definition also lacks references to inclusion and equity; does not refer to integrated approaches;2 and appears decoupled from pressing food and nutrition security, climate change, biodiversity, and circular economy goals. Alongside the definition, the World Bank put forth a schematic and guidance note referred to as the Blue Economy Development Framework (World Bank 2016a; World Bank Group and European Commission 2021), which also exhibits the same limitations as the definition and is largely unfamiliar to and unused by both clients and partners.

The World Bank’s corporate definition of the blue economy is also increasingly unaligned with the way key partners are evolving and articulating their understanding of the blue economy. International actors that work to achieve blue economy aims alongside the World Bank have increasingly clarified that the sustainable blue economy concept converges around the need for a more balanced approach, reconciling economic growth with environmental stewardship and social equity (box 2.1). In the case of the European Union, this clarification represents a sea change compared with the previous definition. The World Bank has historically partnered with the European Union in its blue economy analytics (the Blue Economy Development Framework was originally produced in partnership with the European Commission). Since 2018, the World Bank has been a signatory to the Sustainable Blue Economy Finance Principles hosted by the United Nations Environment Programme Finance Initiative, which—together with the European Commission, the World Wide Fund for Nature, the World Resources Institute, and the European Investment Bank—aims to support the integration of a set of environmental, social, and governance considerations into blue economy investments.

Box 2.1. Articulation of the Holistic Sustainable Blue Economy Aims by the Partners

The European Union. As part of the European Green Deal, the European Union has transitioned its blue economy approach from one focused on blue growth (on jobs and growth), stated in the 2012 Communication, to one focused on the sustainable blue economy, as articulated in the May 2021 Communication. This represents a fundamental reorientation of policy and objectives: a move away from primarily pursuing economic growth—”an initiative to harness the untapped potential of Europe’s oceans, seas[,] and coasts for jobs and growth” (European Commission 2012, 2)—toward achieving balanced growth while integrating climate change and environmental priorities—”replacing unchecked expansion with clean, climate-proof[,] and sustainable activities that tread lightly on the marine environment” (European Commission 2021a, 2). Per its new position, the European Union has indicated that “under a sustainable blue economy, maritime and coastal activities reconcile economic development, improved livelihoods[,] and social inclusion with fighting the climate crisis, protecting biodiversity and ecosystems, using resources responsibly[,] and achieving the zero-pollution ambition” (European Commission 2021b).

The United Nations Environment Programme houses the Sustainable Blue Economy Initiative and is launching the Sustainable Blue Economy Decision Support and Enabling Framework. The latter states that the sustainable blue economy “increases revenue and enables sustainable growth in the marine economy through enhanced services provided by healthy environments; strengthens livelihoods and food security; ensures fair and equitable access to the oceans’ wealth; and contributes to climate change mitigation through renewable energy and de-carbonizing blue sectors” (UNEP, forthcoming). A sustainable blue economy approach overcomes the disconnected way oceans are managed and is fundamental for addressing the three planetary crises (climate change, biodiversity loss, and pollution) and meeting the Sustainable Development Goals.

The United Nations Environment Programme Finance Initiative hosts the Sustainable Blue Economy Finance Principles—a global framework developed in 2018 that is co-signed by the World Bank, the European Commission, the World Wide Fund for Nature, the World Resources Institute, and the European Investment Bank. The principles are designed to guide banks, insurers, and investors in financing a sustainable blue economy in alignment with Sustainable Development Goal 14 (Life below Water). Taken together, the principles offer a road map for ensuring that financial activities and investments in the ocean and coastal sectors are environmentally sustainable and socially equitable.

The World Wide Fund for Nature put forth Principles for a Sustainable Blue Economy (2015), which emphasizes the need for environmental restoration and protection to ensure intergenerational economic and social benefits. A sustainable blue economy “provides social and economic benefits for current and future generations[;] . . . restores, protects[,] and maintains the diversity, productivity, resilience, core functions, and intrinsic value of marine ecosystems[; and] . . . is based on clean technologies, renewable energy, and circular material flows” (WWF 2015, 4). It also promotes an approach that is inclusive, cooperative, and cross-sectoral based on knowledge sharing and the development and application of standards, guidelines, and best practices.

Sources: European Commission 2012, 2021a, 2021b; UNEP 2018, forthcoming; WWF 2015.

Clearly articulating the holistic purpose of the blue economy is important because clients are using the World Bank’s corporate definition to inform their own blue economy strategies and key partners rely on the World Bank to communicate the more holistic aim. The case studies show that clients are using the World Bank’s corporate definition to inform their own blue economy strategies;3 yet these strategies are better at articulating blue growth aims than articulating how triple-bottom-line objectives will be achieved across relevant ministries. Many international, regional, and bilateral development agencies supporting clients with their blue economy development also look to the World Bank to communicate holistic blue economy aims as part of their economic dialogue with clients. However, apart from a few key staff, the evaluation found that there is low understanding among World Bank staff interviewed about the more holistic meaning of the blue economy.4

Articulation of the Blue Economy in Country Diagnostics

The blue economy is being referenced in many SIDS SCDs, and the concept is slowly emerging in coastal state SCDs. Eighteen out of the 84 SCDs in scope reference the blue economy, even though all 84 reference at least one marine sector. Seven out of 12 SCDs for SIDS refer to the blue economy (in the Caribbean, Indian Ocean, and West Africa). Between 2016 and 2019, with one exception (Dominican Republic), the blue economy concept was articulated in SCDs of SIDS, which is not surprising since the concept was put forth by coastal countries. Between 2020 and 2023, with the rollout of increased blue economy analytics, the blue economy concept began to appear in the SCDs of coastal states in Albania, Indonesia, and Kenya (2020); the Arab Republic of Egypt, Bangladesh, Bulgaria, and Namibia (2021); Côte d’Ivoire (2022); and Togo and Panama (2023). The blue economy concept is referenced in five CEMs, of which four are SIDS (Cabo Verde, the Comoros, Mauritius, and São Tomé and Príncipe), and one is a coastal state (Albania).

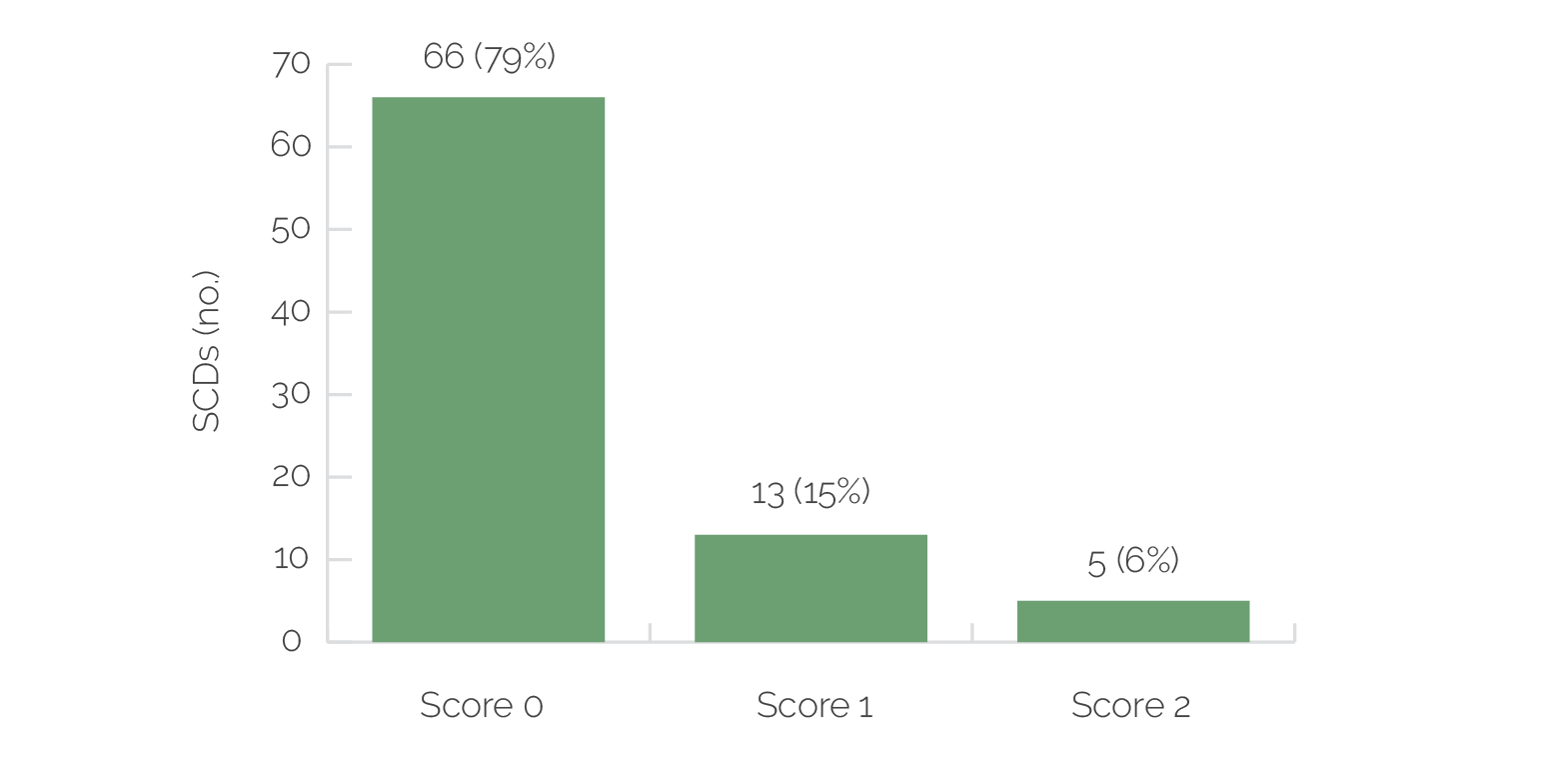

Although SCDs are beginning to reference the blue economy, the comprehensiveness is low overall in many SCDs that reference it. A total of 5 out of 18 SCDs that refer to the blue economy (Kenya, Mauritius, OECS, São Tomé and Príncipe, and the Seychelles) articulated well the need to reconcile economic, environmental, and social aims through cross-sectoral coordination and planning processes that identify synergies and address sector trade-offs (figure 2.1). These SCDs speak to the need to transition away from sector-siloed approaches. They also recognize the connection between marine and terrestrial systems (for example, the way solid waste management or tourism affects coastal and ocean environments or the way that agriculture and deforestation contribute to runoff, sedimentation, pollution, and eutrophication in local coastal systems). The OECS SCD presents a best-case example of how to embed a blue economy approach into development planning: it focuses on the need to balance growth, environmental sustainability, and equity aims; sets milestones for achieving blue economy aims; and highlights associated financing options. The remaining SCDs (13 out of 18) reference the blue economy but continue to address sector issues in silos. Although emerging blue economy opportunities (for example, offshore energy) are cited, there is neither a discussion of sectoral coordination nor an analysis of how to address trade-offs, especially between marine development and environmental sustainability. The absence of a discussion of trade-offs was most notable in SIDS that refer to the blue economy or multiple marine sectors as a source of comparative advantage (for example, fisheries, aquaculture, and tourism) without considering the negative impacts on other sectors (for example, impacts of rapid tourism development on fisheries through increased pollution and land use change or the negative impacts aquaculture facilities can have on coastal tourism).

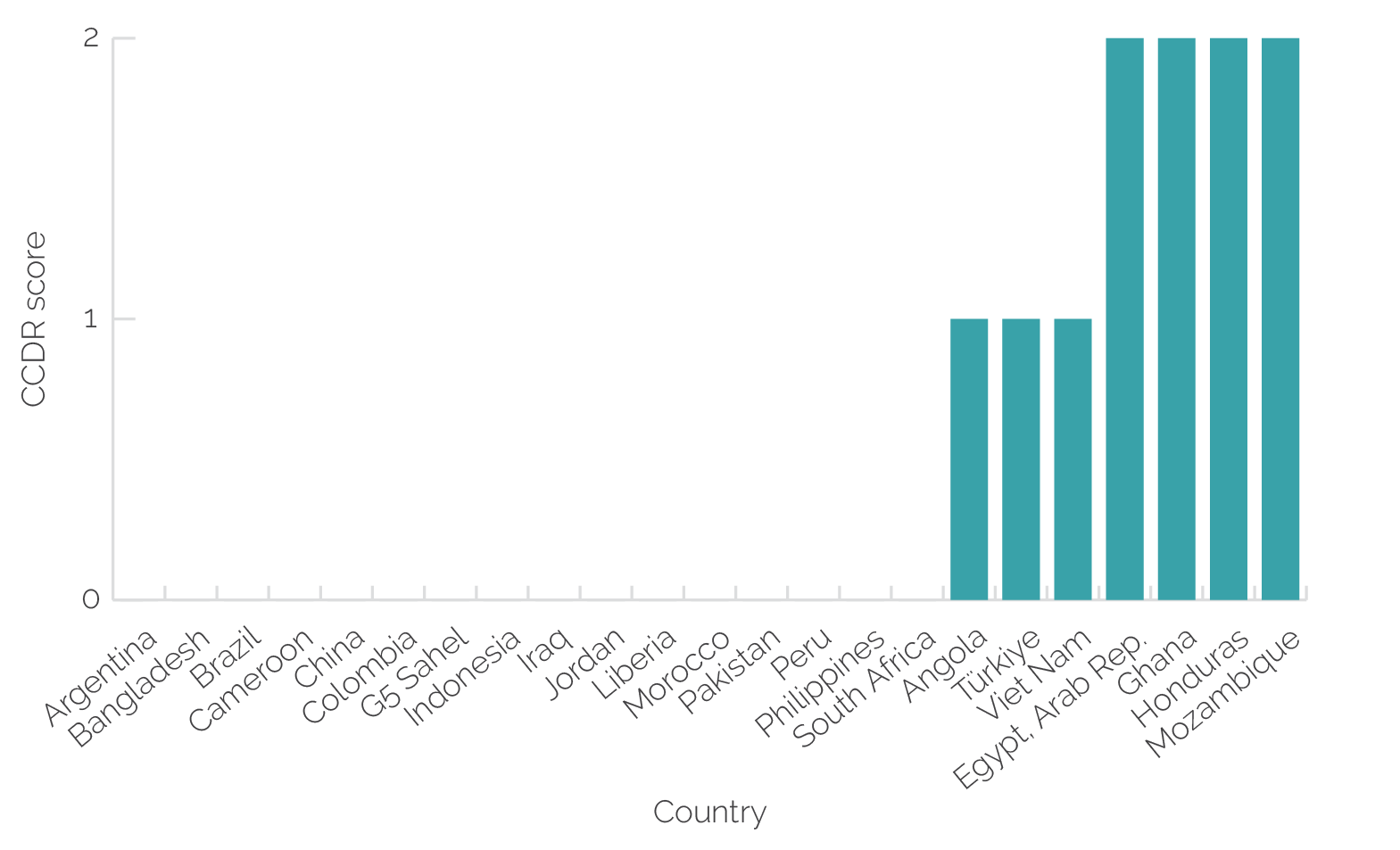

Figure 2.1. Articulation of the Blue Economy in Systematic Country Diagnostics

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: The number of in-scope SCDs is 84. SCD scoring 1: Albania, Bangladesh, Bulgaria, Cabo Verde, Côte d’Ivoire, the Dominican Republic, the Arab Republic of Egypt, Indonesia, Jamaica, Maldives, Namibia, Panama, and Togo. SCD scoring 2: Kenya, Mauritius, Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States countries, São Tomé and Príncipe, and the Seychelles. Scoring rubric: 0 = SCD does not reference the blue economy; 1 = SCD explicitly refers to the blue economy but lacks full articulation of commonly understood meaning, tends to treat sectors in silos, and neglects to identify trade-offs; 2 = SCD comprehensively explains the blue economy as a way of balancing economic, environmental, and social aims and refers to cross-sectoral coordination, planning, and identification of synergies and trade-offs. SCD = Systematic Country Diagnostic.

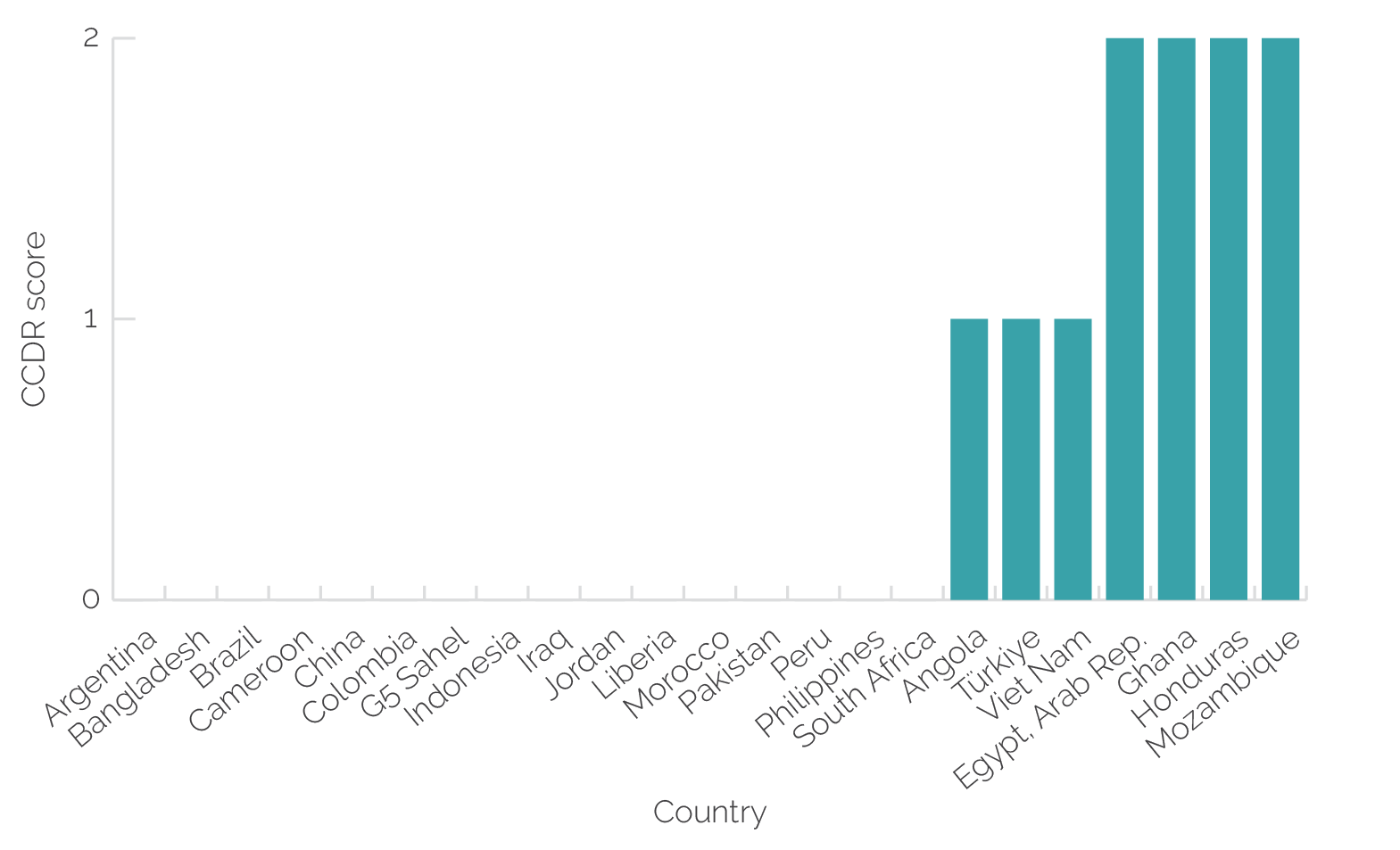

Few CCDRs articulate how a blue economy approach can support national climate change and development goals. CCDRs are new core Bank Group diagnostic reports that have the objective to help countries prioritize the most impactful actions to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and boost adaptation while delivering on broader development goals. Per figure 2.2, only 7 out of 23 CCDRs (for countries in scope) refer to the blue economy; 3 of the CCDRs that do not refer to the blue economy are for countries for which this topic is a key government priority (Indonesia, Morocco, and South Africa), and 2 CCDRs are for countries where the blue economy is explicitly articulated in the SCD. For example, in Indonesia, climate change is woven throughout the country’s Blue Economy Roadmap, yet the CCDR neither refers to the blue economy nor provides much context on coastal or marine issues (as opposed to forests), missing a critical opportunity to diagnose the policy integration and coordinated action needed to achieve blue economy–related climate change aims. Across the cohort, almost no CCDRs discuss the potential of blue carbon toward achieving nationally determined commitments. For example, mangroves, except for Indonesia, are not identified as part of CCDR priorities, which speaks to a gap in identifying nature-based solutions in relation to achieving climate change goals. Conversely, 4 out of 23 CCDRs articulate clear links between marine activities and climate action (scored as 2 in figure 2.2), with Ghana being a best practice example. The Ghana CCDR identifies a blue economy approach as a way to achieve the climate change objectives articulated in the CCDR (box 2.2).

Box 2.2. Articulation of the Blue Economy Approach in Ghana’s Country Climate and Development Report

Ghana’s Country Climate and Development Report advocates for a blue economy approach to enhance climate resilience along the coastline. In the short term, it recommends the establishment of a blue economy framework to maximize socioeconomic benefits and protect blue carbon to support mitigation goals. It cites the need to apply integrated coastal zone management tools for coordinated action and clear delineation of responsibilities across ministries. In the long term, the Country Climate and Development Report calls for a transformative shift from carbon-intensive offshore oil and gas to renewable marine-based energy and a move from infrastructure-based resilience approaches to nature-based solutions. This transition requires policy reforms, capacity development, and innovative financial mechanisms (such as blue bonds and carbon markets) to fund the shift toward a sustainable and resilient blue economy, ensuring a balanced approach that maximizes economic benefits while addressing climate challenges.

Source: World Bank 2022e.

Figure 2.2. Articulation of the Blue Economy in Country Climate and Development Reports

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: The number of in-scope CCDRs is 23. Scoring: 0 = no articulation of the blue economy; 1 = explicit reference to the blue economy (coastal and marine sectors may be referenced, but there is no articulation of how to accurately apply the blue economy concept as a way to achieve climate change and development goals); 2 = explicit reference to the blue economy and demonstration of a comprehensive understanding of the potential of the blue economy approach as a way to achieve climate change and development goals. CCDR = Country Climate and Development Report; G5 = Group of Five.

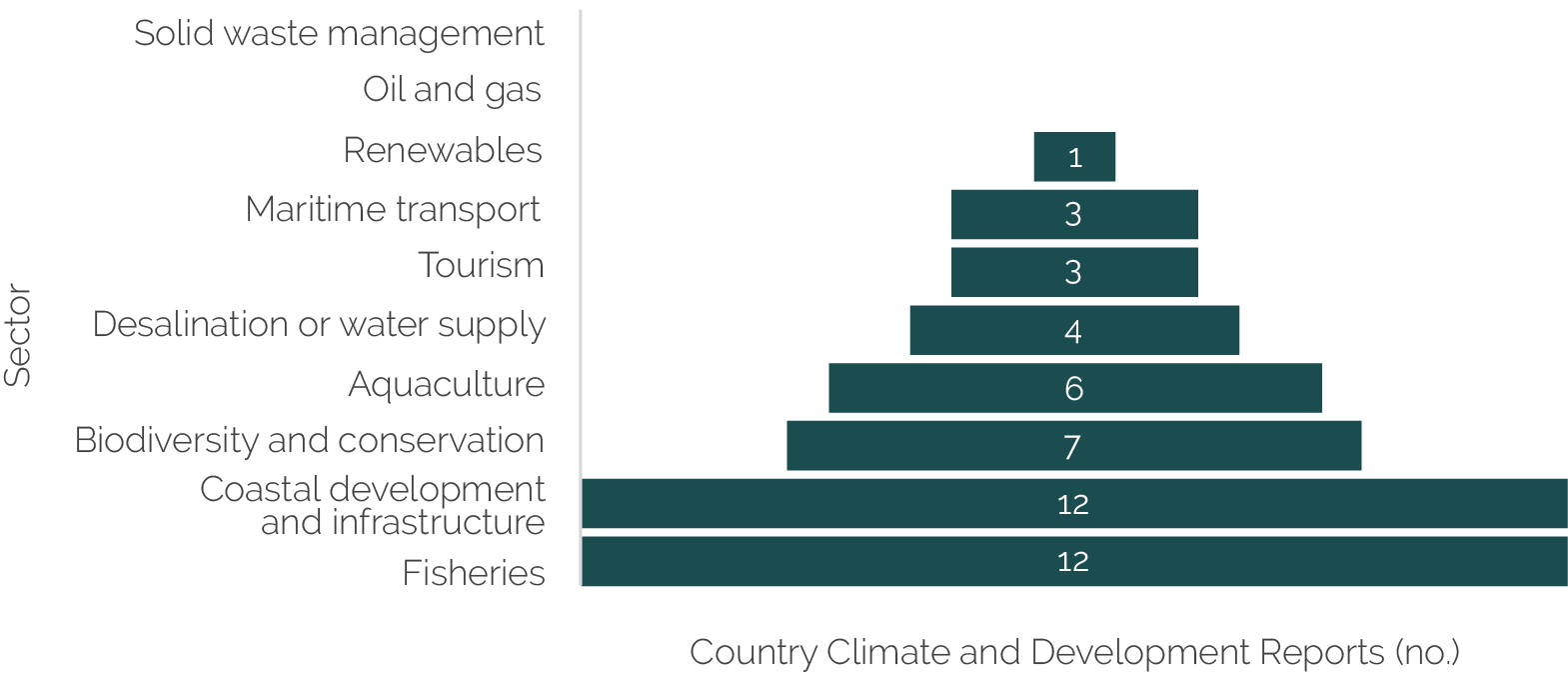

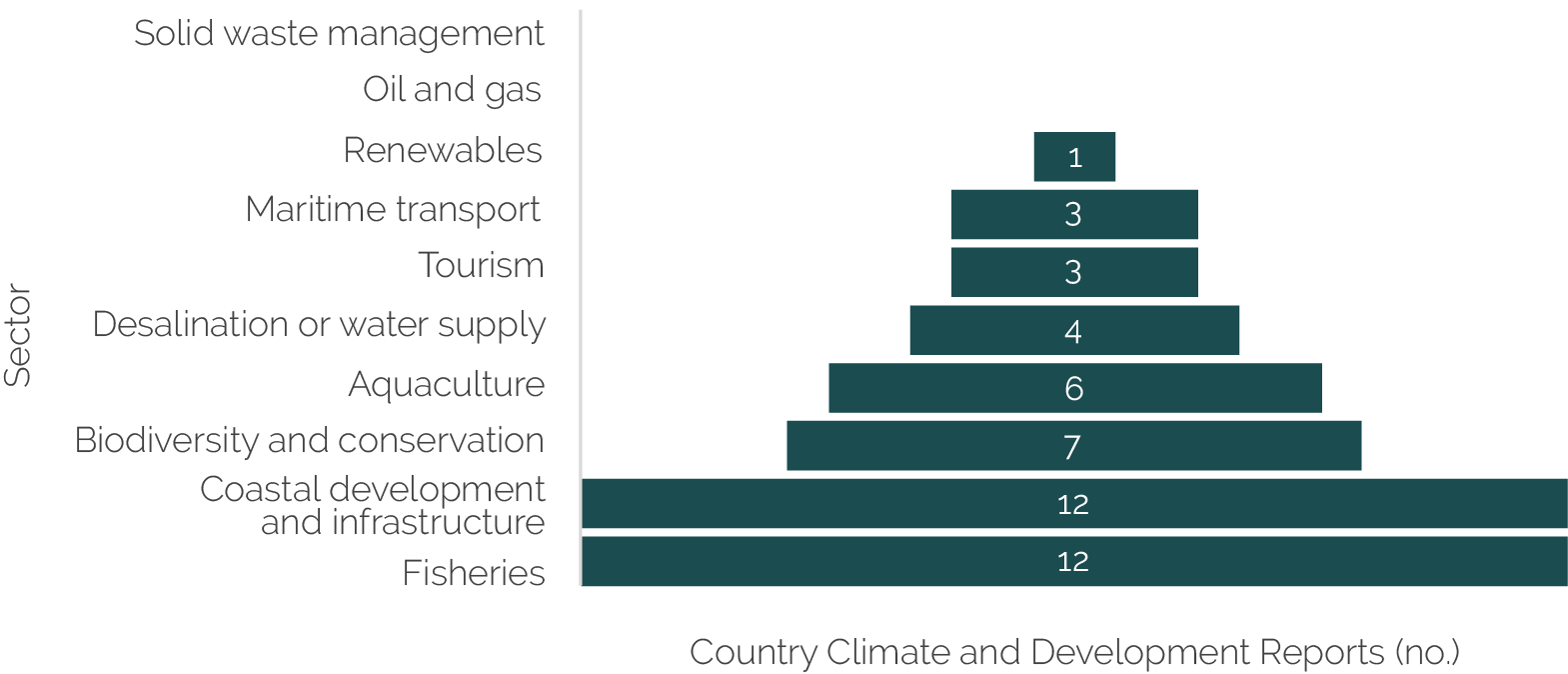

CCDRs also only partially identify risks posed by climate change to marine and coastal areas, and there is scant reference to how emerging blue economy sectors will affect the marine environment. A total of 74 percent of CCDRs (in the countries in scope) identified at least one marine sector at risk from climate change. Risks posed to fisheries and coastal development (that is, housing, industry, and infrastructure at risk from flooding located on the coast) were referenced in approximately half of the CCDRs. However, there were few references, and no robust analyses, of the effects of climate change on other sectors, such as ports and shipping (figure 2.3). Similarly, there is very little discussion across all CCDRs on how some sectors—proposed as part of countries’ mitigation or adaptation strategies—will affect the marine environment, including the development of offshore renewables or the use of desalination plants for water security.

Figure 2.3. Country Climate and Development Reports That Reference Climate Risks to Blue Economy Sectors

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Focused blue economy analytics, largely financed by donors, have been critical for articulating the blue economy in country diagnostics. Almost all (27 out of 29, or 93 percent) of the country diagnostics (SCDs, CCDRs, and CEMs) that refer to the blue economy had prior or parallel access to blue economy–focused analytics. In the two cases where the country diagnostic referred to the blue economy without the benefit of underlying focused analytics, there either was a dedicated senior environmental staff member engaged (Panama) or the World Bank and the government were engaged in dialogue as part of the High Level Panel for a Sustainable Ocean Economy (Namibia).5

Sector analytics, including those focused on fisheries, marine pollution, and waste, have been insufficient to support the transfer of the blue economy concept into country diagnostics. Twenty countries have had access to specific sector analytics focused on a coastal or marine sector, such as fisheries, pollution, and waste management. These analytics did not make explicit the links to the blue economy, and none of the country diagnostics of the countries that had these sector analytics refer to the blue economy. A total of 80 percent of the focused blue economy analytics that informed country diagnostics were financed or co-financed by bilateral donors, including the European Commission, the Commonwealth, the Nordic Development Fund, the German Agency for International Cooperation, and the PROBLUE trust fund. By way of contrast, the World Bank has tended to fund sector analytics.

Articulation of the Blue Economy in the World Bank’s Evolution

The evolution reshapes the World Bank’s vision and mission to include a “livable planet” but omits references to marine ecosystems. As per the September 2023 Development Committee paper “Ending Poverty on a Livable Planet: Report to Governors on World Bank Evolution,” the newly launched Global Challenge Program on Forests for Development, Climate, and Biodiversity does not refer to the blue economy, and actions on biodiversity and nature do not refer to coastal or ocean resources (World Bank 2023a). This reflects a limited interpretation of a “livable planet,” restricted to terrestrial environments, which overlooks the significant role of marine ecosystems in global ecological and economic systems and important land-sea links.

- For more information, see https://live.worldbank.org/en/event/2022/cop27-unleashing-blue-economy-caribbean.

- The PROBLUE trust fund, which is administered by the World Bank, defines the blue economy as the sustainable and integrated development of economic sectors in a healthy ocean (World Bank 2022l). Although this definition acknowledges the need for an integrated approach in the blue economy, it exhibits most of the same limitations as outlined in the Corporate Articulation of the Blue Economy section in chapter 2.

- For example, at the regional level, the African Union Interafrican Bureau for Animal Resources—the regional body charged with helping African countries draft their blue economy strategies—refers to the World Bank’s definition in its country-facing engagements. The government of Belize indicated that the World Bank’s definition of the blue economy is the definition of the blue economy at its official launch of their Blue Economy Development Policy and Strategy and Maritime Economy Roadmap. Indonesia’s 2023 Blue Economy Roadmap also cites the World Bank’s definition.

- Interviews with staff across the World Bank in the country case studies and in covered sectors demonstrate inconsistent awareness of and, in a few cases, a lack of buy-in for the blue economy concept. This finding is further exemplified by the limited integration of the blue economy concept into the reviewed client-facing country diagnostics (that is, Systematic Country Diagnostics, Country Economic Memorandums, Country Climate and Development Reports), as shown in the Articulation of the Blue Economy in Country Diagnostics section in chapter 2.

- There are also two cases where the World Bank performed blue economy—focused analytics where the blue economy has not been articulated in country diagnostics; however, Country Climate and Development Reports have not yet been conducted (Costa Rica and the Pacific Islands). In these countries, it may be anticipated that the forthcoming Country Climate and Development Reports will use the blue economy concept.