Making Procurement Work Better

Chapter 3 | Improving Procurement Economy, Integrity, Transparency, and Fairness

Highlights

Market analyses, prequalifications, and procurement approaches introduced with the 2016 reform could help projects identify and contract qualified suppliers, increasing procurement competitiveness. Open market approaches account for, on average, about 50 percent of procurement, with the lowest use in Africa and the Middle East and North Africa.

Projects mostly use the same procurement approaches as before the 2016 reform and have not consistently applied less familiar approaches, such as rated criteria or negotiation, to improve quality and sustainability. Only about 15 percent of projects use at least two innovative approaches to support quality.

Coaching teams in applied learning, enhancing third-party oversight to reduce innovation risks, increasing country dialogues, and creating staff incentives could help address quality and sustainability approaches. A menu of approaches that consider quality across the procurement cycle is important.

There is an opportunity to use clients’ procurement systems in World Bank–supported projects to ease procurement, save resources, and improve client perceptions about the World Bank.

The reform started a process of using technology to enhance procurement integrity, transparency, and fairness, which can be built on. Remote monitoring of procurement and post review assessment could be enhanced to strengthen integrity, especially for clients with lower capacity or higher risk. Less than 10 percent of projects had a post review report to validate procurement by the second year of implementation. Complaint handling continues to take a long time, an average of about 170 days.

Post reviews and complaints data, which highlight repeat problems in project procurement, can be used to systematically improve the quality of clients’ procurement.

This chapter assesses the reform’s impact on the procurement principles of economy, integrity, transparency, and fairness. Economy refers to the cost and noncost dimensions of procurement, which, for the purpose of the evaluation, includes competitiveness, engagement of qualified suppliers, familiarity with market analyses, and use of procurement approaches that improve quality, costs, partnerships, and social and environmental sustainability. For integrity, transparency, and fairness, the evaluation focused on post-reform improvements to oversight and looked at open procurement data, risk assessments, complaint handling, and monitoring of whether procured goods and services reach communities. The 2016 reform made nominal progress in enhancing procurement’s economy by emphasizing the quality, competition, and sustainability of procurement, with few projects using approaches to support economy in procurement (appendix C). Integrity, transparency, and fairness improved with the introduction of STEP and a standstill period, but oversight and complaint handling remain areas that could improve.

Strengthened Market Analysis That Could Enhance Competitive Approaches and Engagement of Qualified Suppliers

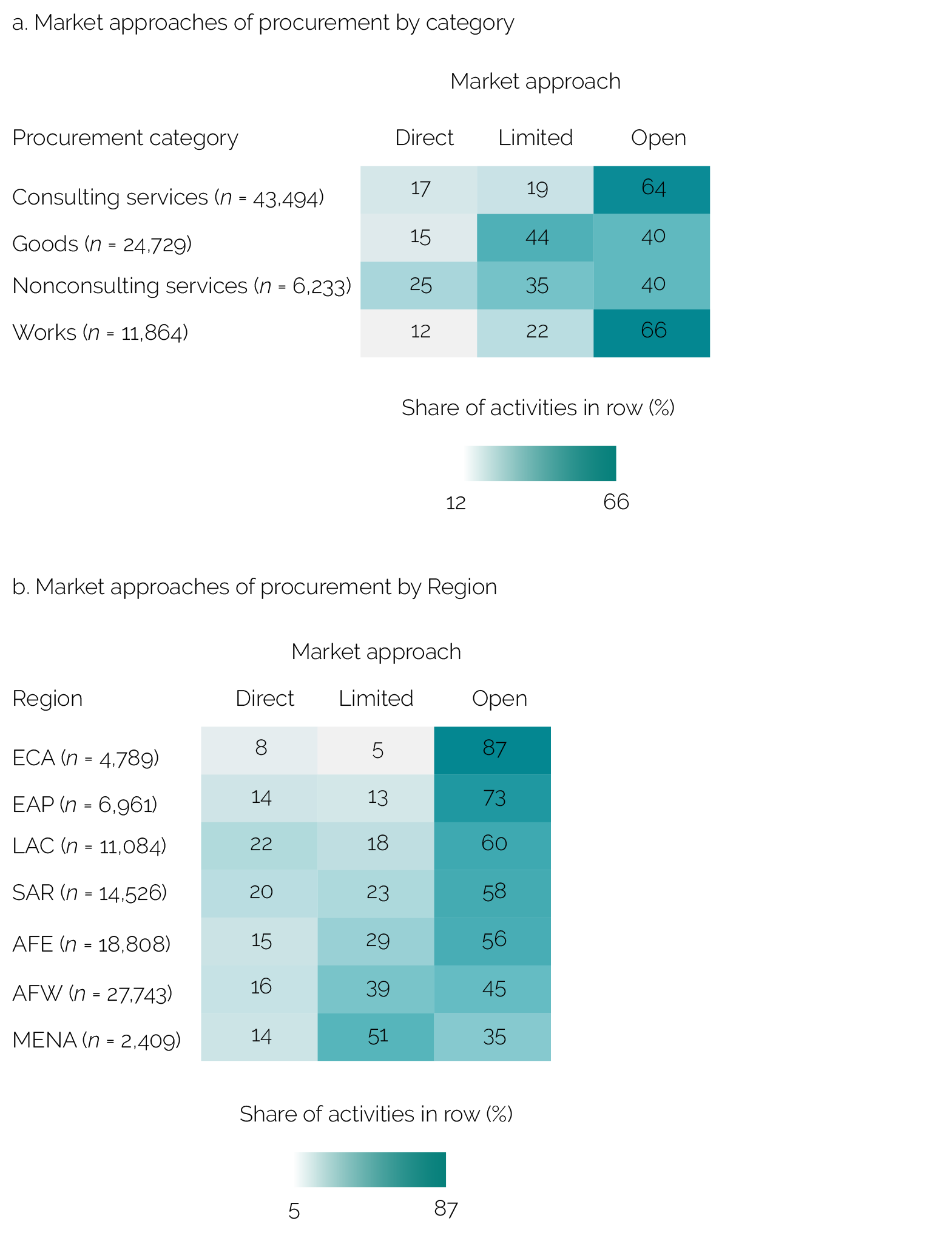

World Bank–supported projects could pay greater attention to open competitive procurement. Just over half of procurement in World Bank–supported projects uses open market competitive approaches. Open market approaches promote procurement quality, fairness, transparency, and cost-effectiveness, but projects often have difficulties attracting enough qualified suppliers to bid. Finding sufficient qualified suppliers ensures smooth processes and prevents delays from rebidding procurement activities.1 The risk of such delays might deter clients from using competitive approaches despite the obvious benefits. Open market approaches are most common for procuring works and consulting services (figure 3.1, panel a), likely because countries have more suppliers in these areas or they are international contracts. Open market approaches are also more common in IDA and IBRD countries than FCS countries and certain Regions, such as Europe and Central Asia (figure 3.1, panel b), likely because of the challenges of market capacity (appendix E). The remaining procurements use limited competitive approaches, in which the client identifies potential suppliers without publicly advertising procurements, or direct selection approaches, in which the client directly contracts a supplier without competition. Limited selections account for about 30 percent of project procurements, and direct selections account for about 20 percent. The use of direct selection in World Bank–supported projects is not significantly lower than in the European Union’s single market countries, where in 2021, about 16 percent of procurement used direct contracting, with rates ranging from about 3 percent to 42 percent. However, the European Commission’s Single Market Scoreboard, which includes data on public procurement, considers direct selection above 10 percent a red flag, though it does not cover the same mix of IDA and FCS countries as the World Bank (European Court of Auditors 2023).

Figure 3.1. Procurement Activities by Market Approach

Source: Independent Evaluation Group Systematic Tracking of Exchanges in Procurement data analysis.

Note: Data include prior and post review activities. The total number of procurement activities with available information on market approach in 687 projects is 86,320. AFE = Eastern and Southern Africa; AFW = Western and Central Africa; EAP = East Asia and Pacific; ECA = Europe and Central Asia; LAC = Latin America and the Caribbean; MENA = Middle East and North Africa; SAR = South Asia.

Using less competitive approaches is optimal when suppliers are limited or speed is essential. Suppliers are often limited during emergencies or in small markets or insecure and remote areas. Direct or limited competitive selection approaches speed up contracting. Direct approaches are about four times quicker on average than open market approaches, and limited competitive approaches are about three times quicker because qualified potential suppliers are already identified (appendix C). In Haiti, a country with insecurity and a small pool of available suppliers, a health project’s limited approaches for procuring small works and medical professionals expedited contracting. In Malawi, a project used a direct approach to procure macronutrient powder from a state-owned enterprise because it was the only supplier with subnational warehouses that could store and distribute the products. During COVID-19, emergency projects used direct approaches to sign contracts and secure limited supplies, which allowed aid to meet critical needs faster.

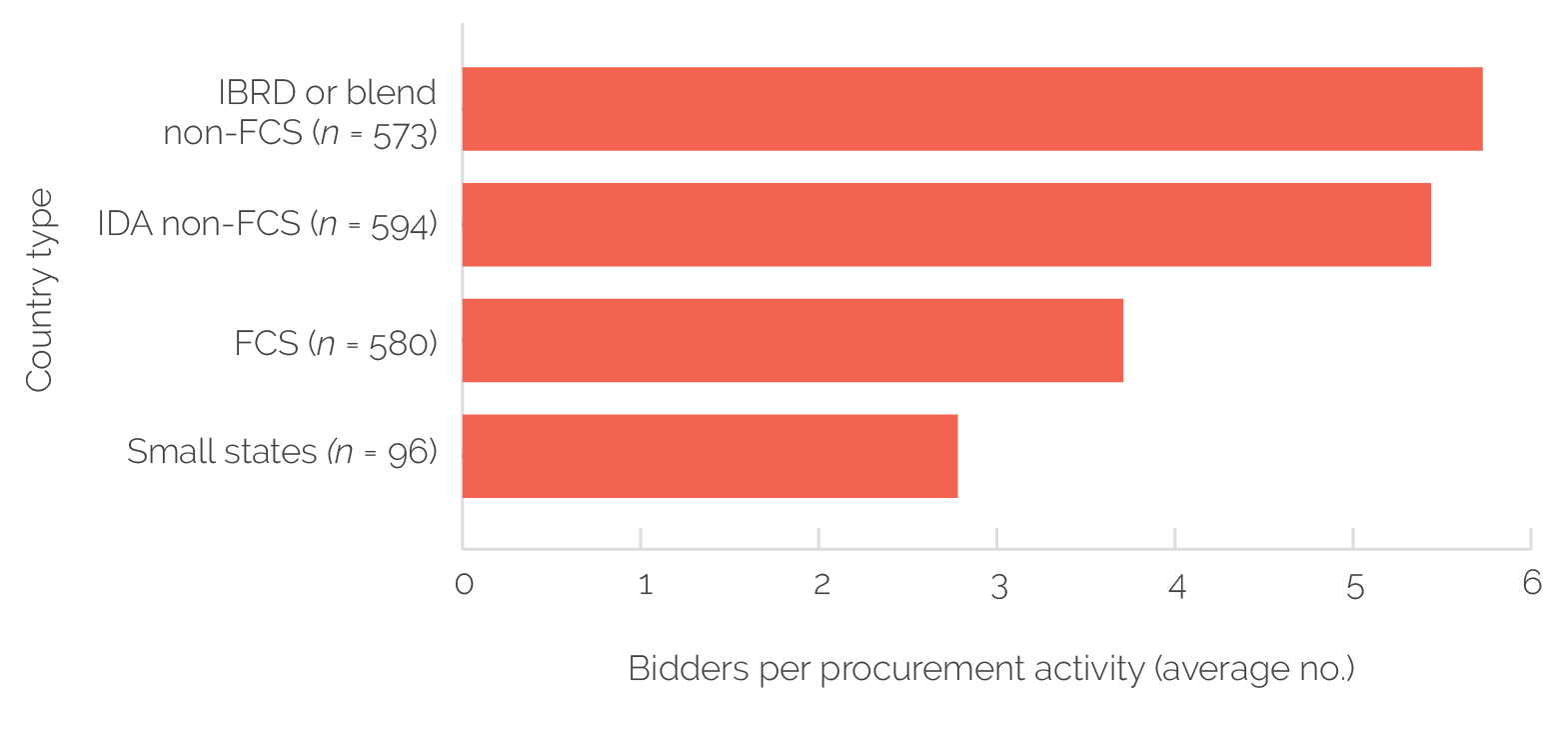

Difficulties in attracting qualified suppliers in less developed markets can delay or even jeopardize project implementation. The challenge of market risk is reinforced by the regression analysis (appendix C), which finds that market risk is negatively associated with project implementation ratings. In some projects, key procurement activities are canceled and relaunched because of a lack of qualified bids. In the Central African Republic’s fragile context, challenges in attracting qualified bids for construction activities delayed a natural resource project. In Sierra Leone, the lack of qualified suppliers caused clients to cancel and relaunch procurement processes for geographical surveys several times. IBRD projects receive the highest average number of bids for procurement activities, largely because these projects take place in more developed markets that are attractive to qualified suppliers. IDA countries receive nearly as many bids on average, and FCS countries and small states receive the lowest number of bids (figure 3.2). The average number of bidders for published public sector procurements in European countries was about three in 2021 (the range was between two and seven bids per contract), suggesting that, in many countries, it may be challenging to attract bidders in public procurement (European Court of Auditors 2023).

Figure 3.2. Bids for Competitive Prior Review Processes by Country Type

Source: Independent Evaluation Group Systematic Tracking of Exchanges in Procurement data analysis.

Note: Data are limited to prior review procurement. The total number of bidders in 1,843 prior review procurement activities with open market approach and available bidder information in 377 projects is 7,310. FCS = fragile and conflict-affected situations; IBRD = International Bank for Reconstruction and Development; IDA = International Development Association.

When done early, prequalifying potential suppliers can save time and enhance the quality of projects, though context should be considered. Less than 3 percent of procurement activities in World Bank–supported projects use prequalification, which consists of preselecting qualified suppliers who will be invited to participate in a procurement process. The preselection process is publicly advertised; hence, it is competitive. It can help clients or country programs preidentify suppliers with a high-quality track record. Case studies show time savings from prequalification if it is done early in project implementation or at the country level. In a project in Eastern Europe, the client used prequalification to identify a pool of qualified suppliers in advance of a procurement activity when the project was still finalizing its technical designs. A regional project in Eastern and Southern Africa benefited from a list of prequalified suppliers already identified from another project in the country. However, prequalification may be unnecessary at times, and using it could cause delays because it is an additional step in the procurement process (ADB 2018). For example, a long prequalification stage delayed a regional transmission line project in East Africa for almost a year.

Market analysis tools, such as procurement strategy documents and risk assessments, are meant to improve procurement but often lack operationally useful information. Clients are expected to prepare the project procurement strategy for development (PPSD), including the market analysis, before the project is approved. At that time, often not all procurement activities are known, and the client’s project implementation team is typically not yet in place. Hence, consultants frequently prepare PPSDs with limited client involvement. Market analysis is a tool to understand the market characteristics for specific works, goods, or services; identify potential suppliers; and help design effective procurement strategies that encourage competition and quality. The market analysis at the PPSD stage is usually done through a desk analysis rather than an outreach to identify potential suppliers and engage with them to customize procurement requirements. A review of PPSDs shows that the PPSD’s market analysis is mostly a theoretical exercise with limited practical value, and that it is rarely an updated living document. Moreover, case studies show that the eventual project implementation teams rarely use the PPSD’s market analysis because it lacks detail to guide the project activities. Interviews suggest that clients could identify actions for market analysis in the project’s first year of implementation when the implementation team is in place.

Well-conducted, early-stage market analysis and engagement can prevent setbacks for projects. In the Kyrgyz Republic, international suppliers did not bid on technology contracts because of the risk the country context poses. In an education project in Malawi, the client canceled and relaunched a procurement process for classroom construction in rural districts because international bidders lacked interest in working in remote areas. In these cases, identifying potential suppliers by engaging with, for example, business associations before starting the procurement process, could have helped customize the procurement approach to market capabilities so it could advance smoothly. World Back procurement staff often echo this shortcoming in their reviews of projects by suggesting that clients use a market analysis to identify and engage quality suppliers and customize procurement approaches.

Practical applied approaches to market analyses are enough to help procurement succeed in unpredictable markets. In a project series in Nicaragua, the client already knew which procurement approaches would work, making it unnecessary to conduct a market analysis. However, conducting market analysis is helpful for project activities that include client procurement staff with limited experience. For example, in Albania, the client procured a local consultant to supervise rural road construction because a market analysis recommended that a supervisor be on-site to oversee the construction. In Nigeria, the client designed a first-time procurement process for an e-procurement system based on the market analysis that recommended using multiple currency bids and performance-based contracting to attract international bidders. Box 3.1 provides examples of three practical approaches to identify potential suppliers to customize procurement to market capabilities.

Box 3.1. Three Practical Ways to Identify Markets for Procurement Activities

Communication with potential suppliers. For example, in a Malawi child development project, the client engaged with the National Construction Industry Council to identify suppliers for small works (which resulted in many bids). In an electricity project in Nigeria, the client communicated with potential suppliers to learn their costs, capabilities, and works, goods, and services that could support project needs.

Desk reviews to identify qualified suppliers. For example, during the preparation of projects in Colombia and the Marshall Islands, clients conducted initial market analyses using suppliers’ databases and later deepened these analyses based on engineering specifications.

Rapid assessments to understand markets. For example, a rapid assessment of a solar energy project in India found that the markets were not well developed. As a result, the project identified national and international suppliers that could be matched to support the project’s wind and solar energy activities. These matches could help national suppliers learn from international ones to develop new market competencies. In an agriculture project in Mozambique, the client’s rapid market screening predicted an uneven distribution of qualified suppliers among the provinces. To manage this, the client procured international and local suppliers in joint work ventures to cover local capacity shortfalls and help develop the competencies of local suppliers.

Source: Independent Evaluation Group case study analysis.

Opportunities to Emphasize a Menu of Approaches That Can Enhance Quality

Clients and TTLs tend to use procurement approaches that are familiar to them rather than unfamiliar approaches that consider quality. Clients do not fully use the greater selection of procurement approaches introduced through the 2016 reform, including e-auctions, which offer efficiency solutions and ways to reach new markets, and requests for proposals, which the reform envisaged for works, goods, and nonconsulting services when used with rated criteria to consider quality in bid evaluation. For works, goods, and nonconsulting services, clients frequently use familiar approaches, such as requests for quotations or requests for bids, without combining them with innovations, such as rated criteria, negotiation, or competitive dialogue, to enhance quality (figure 3.3, panel a).2 Requests for bids are frequently used for higher-value and international procurement (appendix C), whereas requests for quotations are often used for smaller-value activities (figure 3.3, panel b). Most consultants are individuals and firms selected based on their qualifications. IEG’s 2014 procurement evaluation similarly found limited use of quality-based selection for consulting services that considers the technical proposal before cost (World Bank 2014). In procurement reviews, World Bank procurement staff repeatedly recommend that clients use negotiation to reduce costs or refine the technical details of consulting services to help ensure quality; however, this rarely happens.

Figure 3.3. Procurement Approaches Used by Projects by Category and Value

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: The figure shows the share of procurement approaches used in procurement activities by procurement category and value. The total number of activities with available information on procurement approaches in 681 projects is 75,369.

Innovative procurement approaches can help clients improve the quality of World Bank–supported projects by balancing cost considerations. Case studies show that when projects are supported to carry out innovative procurement approaches client satisfaction often happens because specific needs for project activities are addressed. Examples of such innovative procurement approaches, include engaging suppliers based on technical quality criteria, not only cost, for solar and wind power contracts; ensuring performance-based measurement of contracts for delivering services; using procurement to empower local leadership in communities; matching international suppliers to help develop local small business competencies; and agreeing on technical specifications before setting the cost of the procurement. Box 3.2 describes examples of innovative procurement approaches that address needs in projects. Some 40 percent of projects use at least one less common procurement approach—often two-envelope system bidding—that allows for discussion on technical specification quality before reviewing cost. Only about 15 percent of projects use more than one innovative procurement approach, despite the many procurement activities in a project. Other examples provided in figure 3.3 are approaches that are used less frequently. Because of social distancing mandates during COVID-19, some clients used e-auctions to allow for transparent reach of suppliers across geographies.

Box 3.2. Examples of Innovative Approaches Facilitating Projects

Contracts with performance indicators to track outputs and their quality. For example, in Ghana, a performance-based contract for river dredging used a two-stage procurement to increase the quality of bids and an external independent agency to certify outcomes before payment. In Brazil, a project used a long-term contract for water connection works. The contractor was paid part of the contract price after completion of the works based on performance standards and output levels, such as the number of inhabitants connected to the networks.

Procurement approaches that consider maintenance for a good or service. For example, in Kenya, a project procured solar mini-grids through an international contract that included seven years of supplies, installation services, and maintenance. In the Kyrgyz Republic, a digital connectivity project followed a two-segment approach to contracting: the first contract established the infrastructure and set up the services, and the second contract ensured the delivery of those services for seven years.

Negotiating contracts to reduce costs and specify technical quality. For example, a project in the Kyrgyz Republic used negotiation to procure an operator service for broadband access. A probity assurance auditor addressed transparency concerns by overseeing negotiations. In a Pakistan project, a probity adviser improved the transparency of negotiation with the supplier during contracting of a large enterprise resource planning system.

Grouping together similar procurements to ease the processing burden on clients. For example, a Burkina Faso financial inclusion project used a framework agreement to group together the procurement of separate mobile network operators. In Mozambique, a project grouped the procurement of suppliers that would carry out similar agricultural surveys in four different provinces to save time and effort. In Lesotho, a project procured COVID-19 vaccines from suppliers based on agreed pricing, and quantities were then staggered for delivery. In Nicaragua, a project procured furniture and construction materials in one contract for multiple schools to reduce transport costs to the project’s remote sites and ease processing for the client.

Source: Independent Evaluation Group case study analysis.

Third-party oversight could be enhanced to encourage clients to take advantage of less used procurement approaches to foster their confidence about the integrity of these approaches.3 For example, the use of approaches such as negotiations and best and final offer could be enhanced with third-party oversight. Negotiations and best and final offer set the activity’s prices, technical terms, and conditions before the contract is awarded. About 28 percent of requests for proposals and 5 percent of requests for bids use these two approaches, mainly for international contracts. These approaches are nearly absent from national contracts. Clients are wary about the potential integrity risks—that is, the risk that the clients’ negotiation with suppliers will be seen as a form of corruption. As such, the biggest barrier to expanding clients’ use of negotiations or best and final offer is understanding of transparent oversight mechanisms. In a project in Europe and Central Asia, the use of third-party probity assurance to monitor the negotiation worked well once addressed with the client.

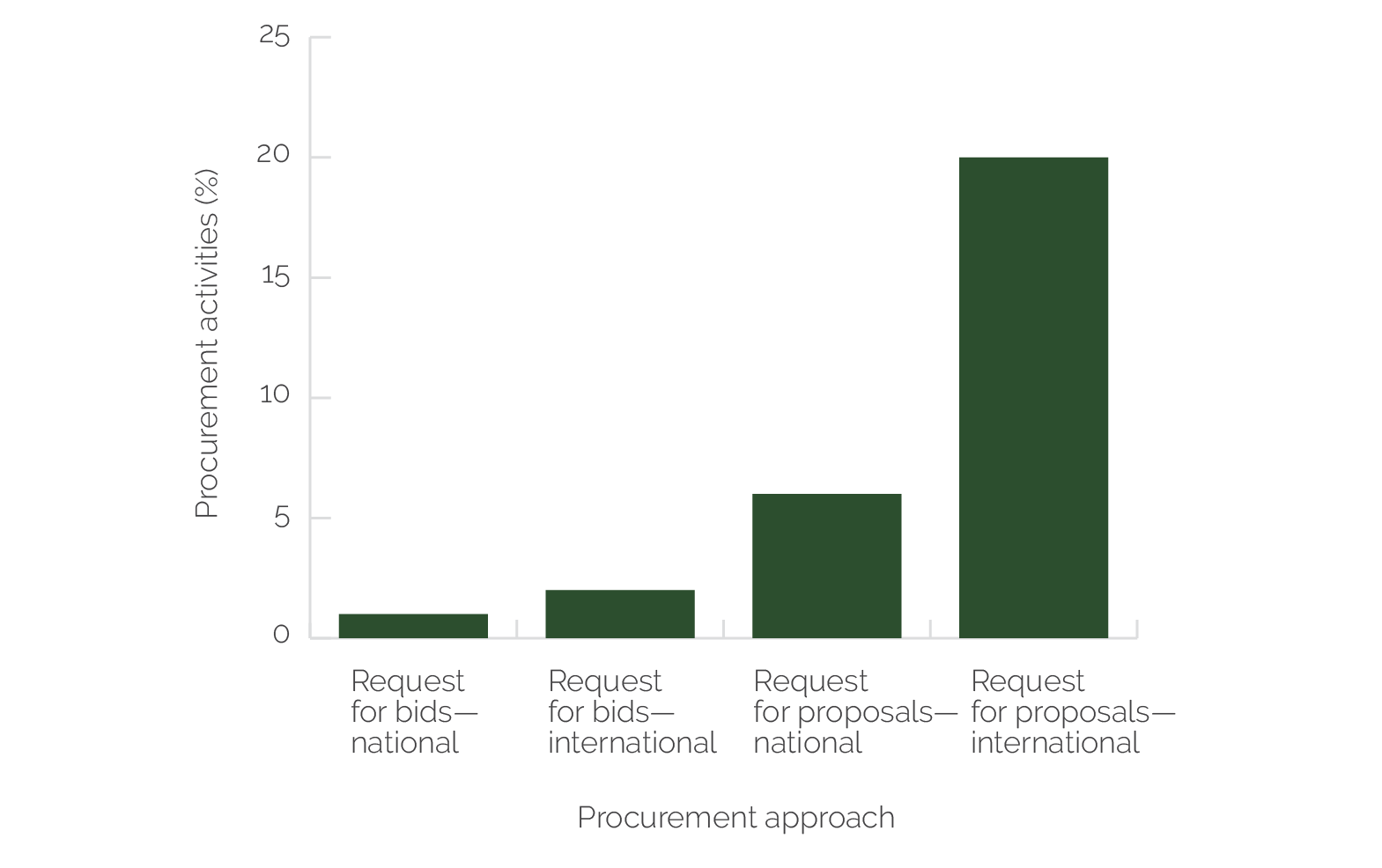

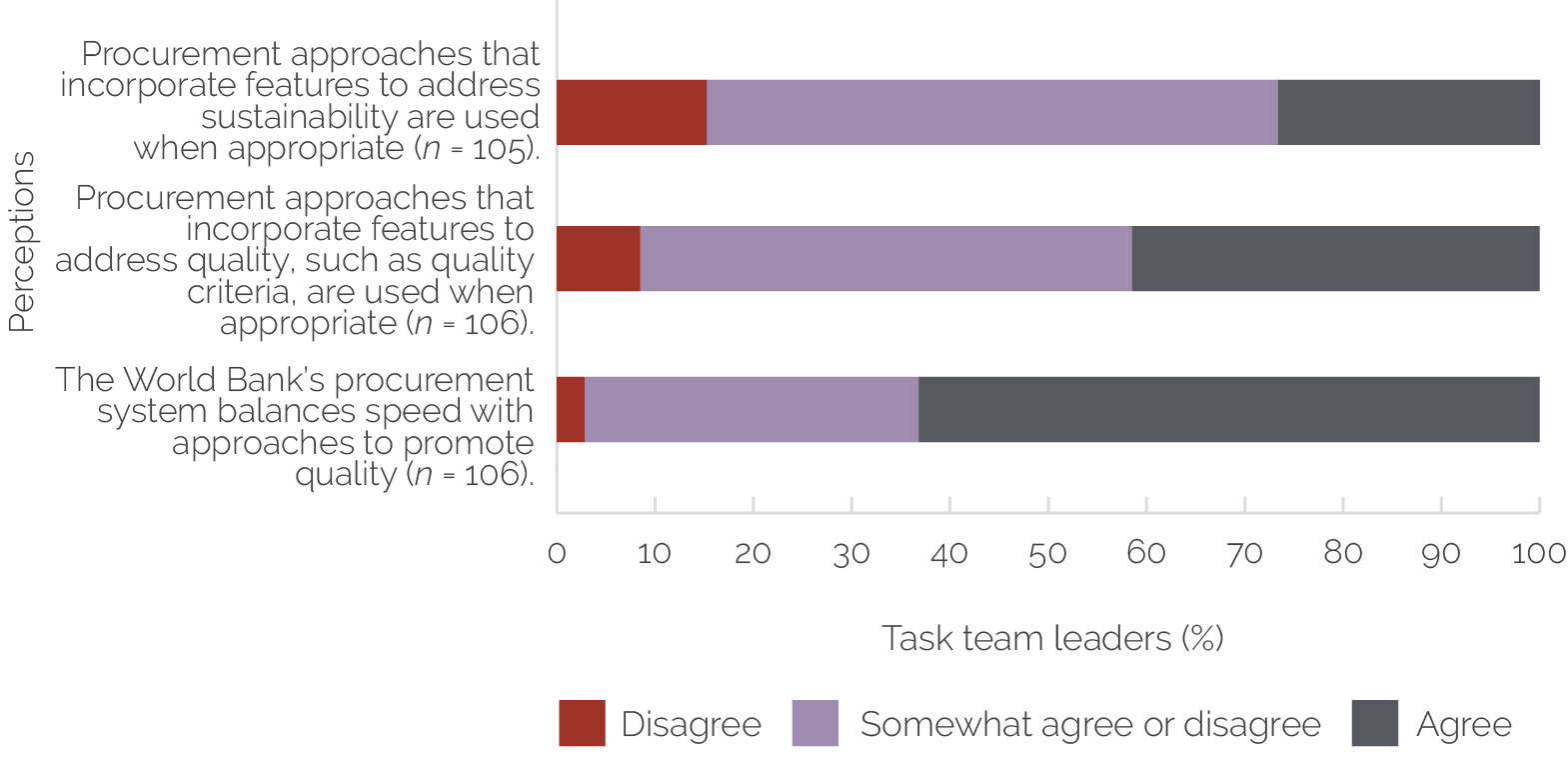

Clients’ use of rated criteria to enhance quality is limited in both national and international procurement. Since the procurement reform, the World Bank has emphasized improving procurement economy by encouraging rated criteria—or nonprice factors such as quality, sustainability, and innovative aspects—to evaluate bids. Quality evaluation by clients is common when procuring consulting services but rare when procuring other project activities. Case studies show that World Bank staff and clients are positive about rated criteria and perceive that the approach could help improve the quality of suppliers. As of August 2023, clients used rated criteria in the procurement of works, goods, and nonconsulting services in about 2 percent of procurement activities,4 with higher use reported in international procurement. International requests for proposals show the highest use of rated criteria (figure 3.4). The Asian Development Bank has experienced similar challenges in the uptake of rated criteria, which it ascribes to the lack of clients’ skills and the perception that they cannot depart from their national laws and regulations (ADB 2023). In European countries, by comparison, nearly half of contracts (42 percent) are awarded based on rated criteria and not simply the lowest price (European Court of Auditors 2023). However, in 2021, in eight European Union member states, the level of awards in favor of the lowest price exceeded 80 percent. In the TTL survey, TTLs do not agree that clients use rated criteria and other features to address quality when appropriate in projects (figure 3.5).

As of September 1, 2023, the World Bank requires rated criteria as the default approach for most international procurement, demonstrating leadership among multilateral development banks to start to improve procurement quality. However, international procurement is only 10 percent of procurement in terms of volume and about 37 percent in terms of value. Rated criteria and other quality features could help national procurement because this is the area where most procurement occurs in World Bank–supported projects.

Figure 3.4. Use of Rated Criteria for Assessing Quality in Selected National and International Procurement

Source: Independent Evaluation Group Systematic Tracking of Exchanges in Procurement data analysis.

Note: The figure shows the share of rated criteria used in procurement activities for requests for bids and requests for proposals. The total number of procurement activities in works, goods, and nonconsulting services with rated criteria is 126. National and international = market approach used by the procurement.

Figure 3.5. Task Team Leaders’ Perceptions of Quality and Sustainability Approaches

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

World Bank staff and clients do not understand well the concept of quality and how to apply it. Procurement quality refers to the noncost factors that increase procurement value and the balancing of those factors with costs throughout the project cycle to fit project needs. Case studies show that clients and World Bank staff use a range of practices to address quality at different stages of procurement (although different practices may be applied by different task teams), and that there could be a greater emphasis on aspects of quality across the procurement cycle (box 3.3). The World Bank’s commitment to use rated criteria could be part of a comprehensive strategy to help projects improve procurement quality along with, for example, market analyses, prequalification practices, technical aspect negotiations, technical requirement clarity, and contract monitoring.

Box 3.3. Quality Considerations throughout the Procurement Life Cycle

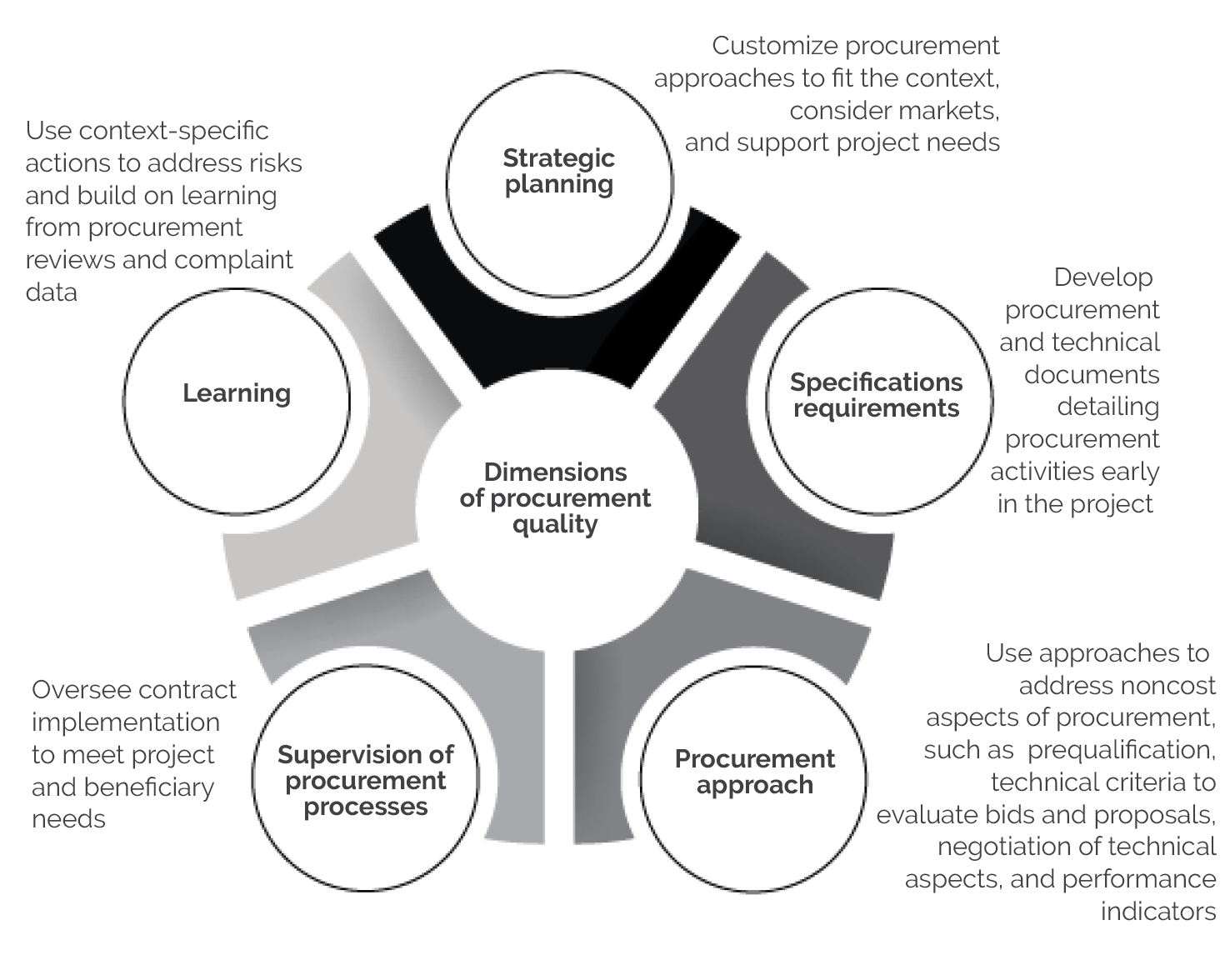

Attention to quality to enhance technical and noncost aspects of procurement in practice often happens at different stages of a project’s processing and management of procurement. Quality can happen, for example, through strategically planning procurement approaches to foster quality, using clear technical specifications, applying criteria to assess technical aspects, conducting market engagement to identify experienced suppliers, negotiating to discuss technical aspects, paying attention to contract management during supervision, and learning from procurement reviews and problems identified by complaints (figure B3.3.1). For example, a project in Nigeria used a comprehensive approach to enhance quality, including a procurement strategy, market analysis, customized technical specification documents that describe procurement needs and align with market expertise, performance indicators, requests for proposals, and rated criteria. Projects used remote monitoring and databases to adaptively manage contracts during supervision. Projects also enhanced procurement processes using feedback from the World Bank’s procurement reviews and, in some cases, information on procurement complaints.

Figure B3.3.1. Procurement Quality Considerations in Projects at Different Stages

Source: Independent Evaluation Group based on case study analysis.

Emphasis Placed on Sustainable Procurement and Alternative Procurement Approaches

Sustainable procurement approaches can improve procurement outcomes, especially during the World Bank’s current transformation process. Sustainable procurement requires incorporating sustainability considerations throughout the entire procurement process. This means that sustainability considerations, such as energy efficiency considerations, could be reflected in the technical specifications, evaluation criteria, contract conditions, and contract management for goods or works to be procured. It can also be used to foster social and economic sustainability, such as gender equality and local private sector development. The literature suggests that the benefits of sustainable procurement could be significant for client governments, although there needs to be leadership and collaboration across units to guide implementation (Molino 2019). With the World Bank’s new focus on a livable planet and the introduction of Global Challenge Programs that strongly focus on environmental and climate considerations, solutions that accept sustainability considerations in procurement will likely become very important. Coordination will also be needed between procurement staff and the World Bank’s Environmental and Social Framework to expand sustainability approaches.

Enhancements to procurement sustainability are not fully applied at the World Bank or other international organizations. Before the 2016 reform, there were already examples of sustainable procurement approaches in projects, but these were never systematically increased in the portfolio (World Bank 2014). Addressing sustainable procurement has mostly been limited to meeting the requirements of the World Bank’s Environmental and Social Framework. PPSDs also briefly mention sustainability as it is one of the fields in the template (appendix E). Sustainable procurement approaches to promote, for example, green technologies, gender equality, supply chain reliability, and local market development are rarely detailed in technical specifications. Moreover, when projects implement sustainable procurement, such as using gender criteria for contracting, results are rarely monitored. TTLs agree, stating in their survey that clients do not consider sustainability features in procurement when appropriate (figure 3.5). The European Union’s reform of its procurement system in 2014 and the Asian Development Bank’s reform in 2017 also encourage greater consideration of environmental and social aspects in procurement, but both have seen little success (ADB 2023; European Court of Auditors 2023).

World Bank staff and clients show a positive attitude toward sustainable procurement, although a lack of experience in implementing it hinders uptake. In the case studies, World Bank staff and clients recognize that sustainability aspects are important but do not understand what procurement can achieve. In interviews, TTLs and clients say that they require concrete guidance and examples of addressing sustainable procurement in their sector. In the survey, about 20 percent of TTLs agree that they have the necessary experience to advise clients on sustainable procurement approaches (appendix G). IEG’s 2014 procurement evaluation echoes this, reporting that World Bank staff and clients’ lack of understanding of sustainable procurement approaches hinders their uptake (World Bank 2014).

Several projects use alternative procurement arrangements (APAs) by relying on development partners’ procurement systems, but none follow national systems. APAs are procurement arrangements that projects can use instead of the World Bank’s procurement regulations. APAs might be the procurement arrangements of another multinational or bilateral organization or of a client’s agency or entity (World Bank 2020b). Approximately 2 percent of World Bank–supported projects use the APAs of other multinational or bilateral organizations, but none use the procurement arrangement of a client’s agency or entity. Clear reasons exist for the limited uptake of APAs. In the survey, half of World Bank procurement staff perceive APAs as difficult to justify because clients rarely meet the necessary requirements. About 40 percent of TTLs think that management does not promote APAs. Feedback from the case studies suggests that APA use is limited because World Bank procurement staff perceive risks from relying on client agencies to regulate procurement. The full use of country systems may be further limited by the requirement that clients use the World Bank’s standard anticorruption clauses in every contract.

APAs could provide benefits to both the World Bank and its clients. About one-third of World Bank procurement staff and half of TTLs report that clients in higher-capacity countries are interested in using their own national systems for procurement. An APA can facilitate this. IEG’s 2014 procurement evaluation also notes that projects can apply partial APAs that rely on national systems while also relying on World Bank staff to support capacity strengthening (World Bank 2014). Using national procurement systems for certain high-capacity countries with low procurement risks might speed up some procurement in World Bank–supported projects, save clients’ and World Bank resources, and improve clients’ perceptions about the difficulties of procurement in projects. However, shifting toward client systems will require greater attention to procurement capacity strengthening and additional skills that some World Bank procurement specialists might have to acquire. In development policy loan and Program-for-Results financing, the World Bank carries out the necessary accountability assessment and capacity strengthening. In the survey, about a quarter of procurement staff report that APAs could simplify procurement when the project is cofinanced by other development partners. For example, the World Bank allowed an APA to finance a metro system together with the Inter-American Development Bank and the European Investment Bank and a water supply and sanitation project in the Pacific Islands with the Asian Development Bank.

Change Management That Emphasizes Coaching, Dialogue, and Incentives to Facilitate Quality and Sustainability

TTLs and clients report that they require learning to help them apply APAs and quality and sustainability procurement approaches. Change management requires targeted applied support. TTLs and clients hesitate to apply unfamiliar innovative approaches to address quality and sustainability without coaching support from World Bank procurement staff. The case studies show that clients and task teams who apply innovative approaches typically learn as they go without much assistance (which can delay projects). In a project in Nigeria, World Bank procurement staff coached clients to successfully implement quality procurement, which combined market analysis, rated criteria, and performance-based criteria. In interviews, TTLs report that APAs are still unfamiliar to them, and staff require more learning around the responsibilities for APA procurement oversight.

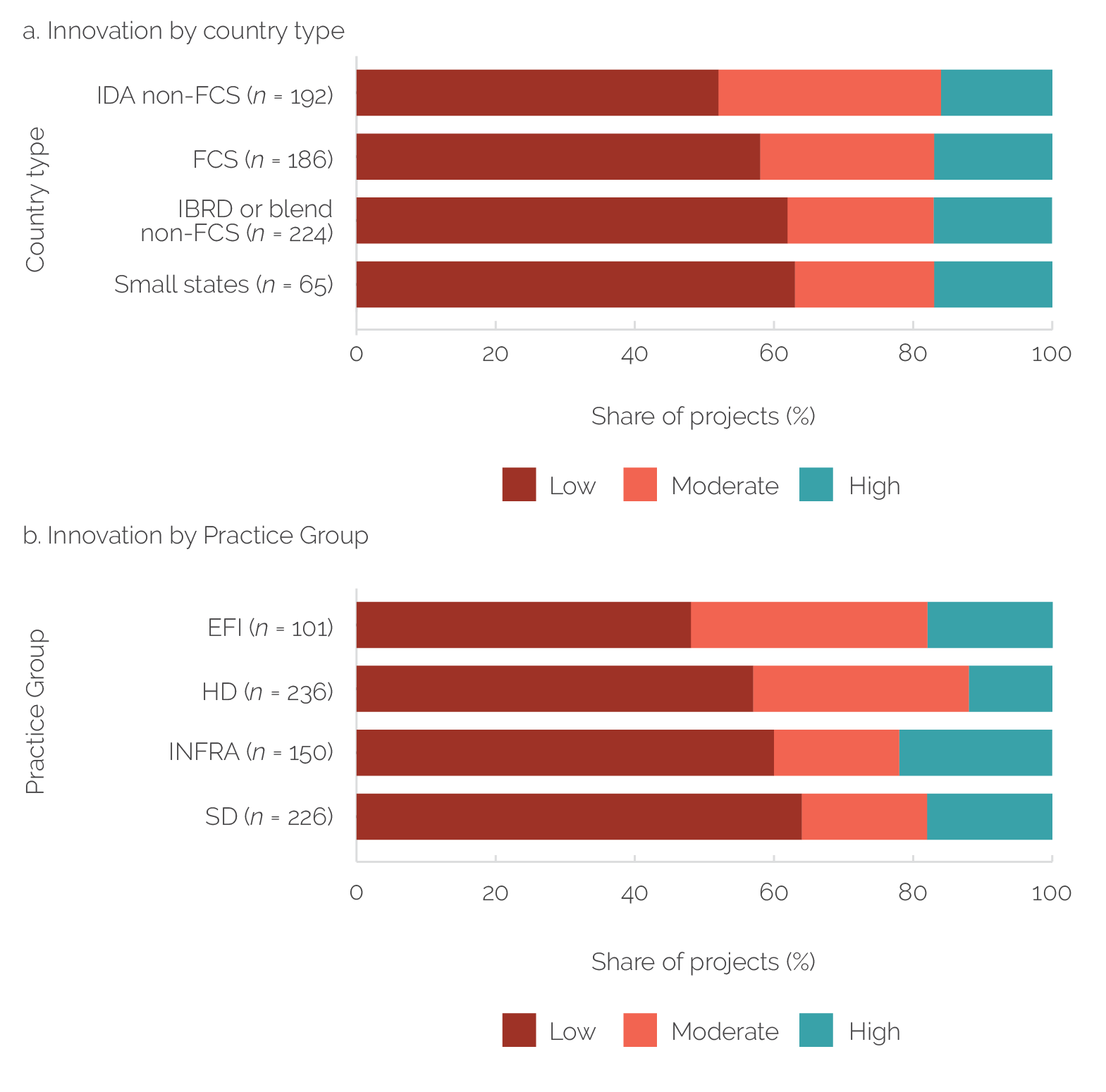

Clients who receive World Bank technical support to overcome the risk of new approaches are more likely to innovate. Projects in IDA and FCS countries use more innovative procurement approaches than in IBRD countries. Among Practice Groups, innovation is lowest in Sustainable Development and highest in Equitable Growth, Finance, and Institutions and Human Development (figure 3.6). The greater use of innovative approaches in IDA and FCS countries can, in part, be explained by the greater support those low-capacity clients receive from World Bank procurement specialists. Clients are more comfortable taking risks when there is support to help them learn. Furthermore, the Human Development Practice Group received more World Bank procurement staff support than other Practice Groups during COVID-19.

Figure 3.6. Use of Innovative Procurement Approaches by Country Type and Practice Group

Source: Independent Evaluation Group Systematic Tracking of Exchanges in Procurement data analysis.

Note: The figure shows the extent to which projects use innovative procurement approaches by country type and Practice Group. Levels are based on the number of innovative procurement features in a project: low is zero innovations; moderate is one innovation; and high is two or more innovations. The measure includes 12 innovative procurement features: alternative procurement arrangements, requests for proposals, rated criteria, best and final offer, negotiations, competitive dialogue, one-stage two-envelope bidding, e-auctions, service delivery contracts, public-private partnerships, performance-based conditions, and community-driven development. The total number of projects is 713. EFI = Equitable Growth, Finance, and Institutions; FCS = fragile and conflict-affected situations; HD = Human Development; IBRD = International Bank for Reconstruction and Development; IDA = International Development Association; INFRA = Infrastructure; SD = Sustainable Development.

Stronger incentives could encourage World Bank procurement staff to promote innovative and sustainability procurement approaches to clients. The case studies suggest that World Bank procurement staff often lack the space in their work program to learn how to support new procurement approaches or help clients design innovative approaches. Similarly, in interviews, procurement staff often report that they have limited time to help clients carry out innovative procurement approaches in projects, despite seeing their value. That said, the Governance Global Practice and procurement management in regions led a change management process to implement the reform, which was intended to integrate quality and sustainability approaches into procurement processes. However, change management has not yet supported the consistent implementation of quality and sustainability approaches across the portfolio, where they are fit for purpose. There could be more emphasis on strategic, portfolio-wide incentives to encourage applied learning of procurement staff to help projects adopt innovative and sustainability procurement approaches.

TTLs and clients state that enhanced policy dialogues and strengthened capacity could help them adopt quality and sustainability approaches. Clients welcome the use of innovative procurement approaches to improve project implementation, but they are concerned about the integrity risks related to using new approaches and the alignment of the approaches with national laws. The main constraints on countries implementing these approaches are pushback from political leaders and the lack of supportive rules and regulations in the country (Fisher 2013; Zaidi et al. 2019). The case studies also show that TTLs and clients want more dialogue and support at the country level to help the transition to using less common sustainability procurement approaches. Clients also appreciate adapting standard bidding documents to their country context and having access to examples of specifications and terms of references to better understand procurement approaches in international and national procurements.

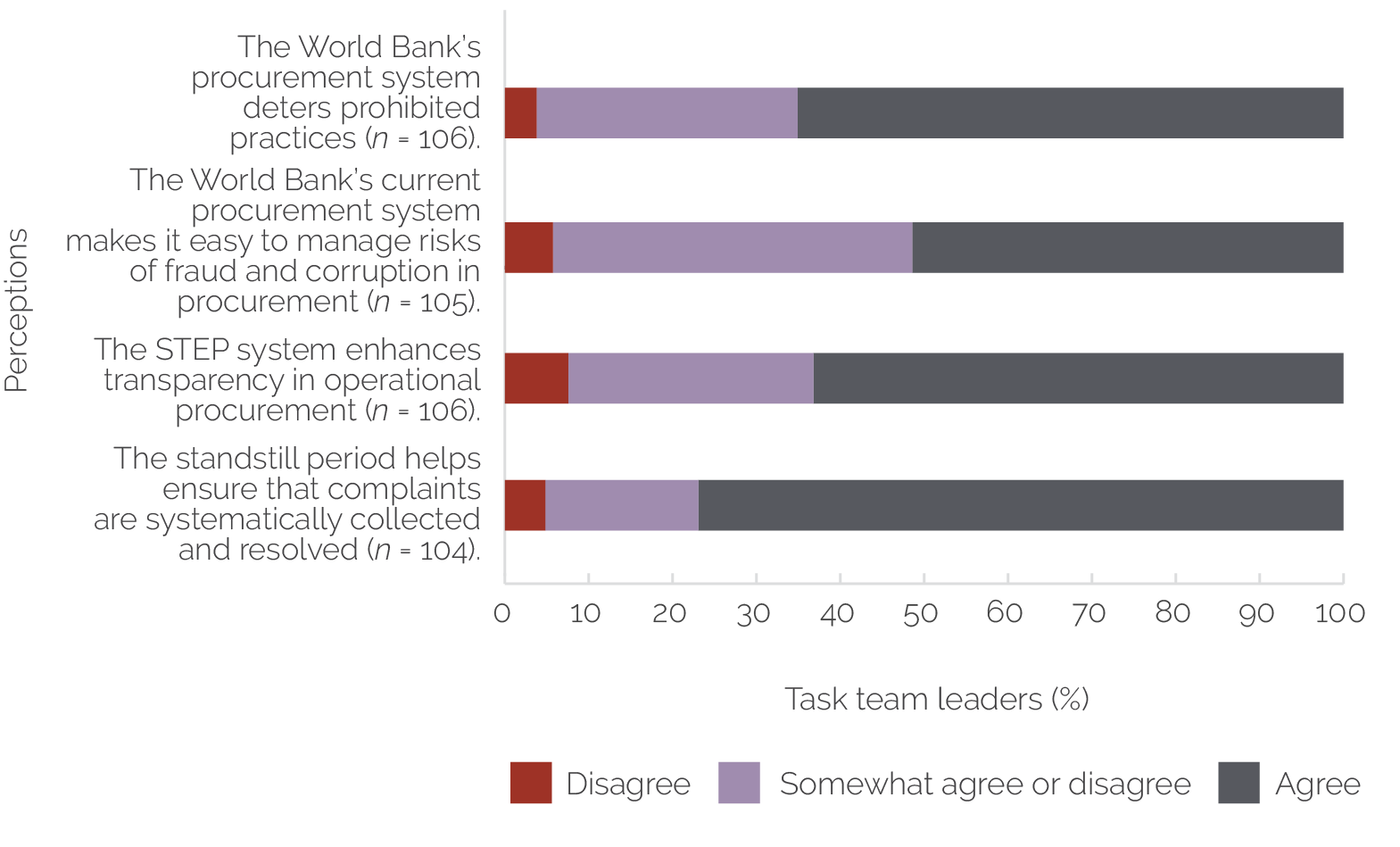

Technology and Transparency, Integrity, and Monitoring

STEP increases transparency and integrity by tracking procurement activities and publishing contract data. STEP tracks procurement transactions in a single website, simplifying transactions and making them easier to oversee. Most World Bank staff—about two-thirds of procurement staff and more than half of TTLs—agree that STEP enhances transparency (figure 3.7). STEP allows the World Bank to routinely publish contract data online, with information on over 80 percent of procurement activities now available publicly. Most TTLs also agree that STEP deters prohibited practices and mitigates the risk of fraud and corruption. This is consistent with the case studies that emphasize the contribution of STEP to the transparency of the procurement process. Moreover, the Integrity Vice Presidency of the World Bank uses STEP data to detect integrity risks.

Figure 3.7. Task Team Leaders’ Perceptions of Transparency and Integrity Changes since the Reform

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: STEP = Systematic Tracking of Exchanges in Procurement.

One challenge for contract management5 is that STEP does not link to the World Bank’s financial management information systems. The case studies demonstrate that clients want systems that integrate financial management to oversee procurement in World Bank projects. Currently, there is no institutional mandate to coordinate financial management and procurement oversight. As a result, the financial management information system and STEP are separate—with the financial management information system used for financial management and STEP for procurement oversight. In interviews, World Bank staff and clients stated that linking the two systems would provide a unified, comprehensive picture of a project’s procurement and financial management, thereby improving contract management.

The World Bank could have a more consistent process for monitoring whether procured goods, works, and services reach beneficiaries. Tracking is especially difficult in subnational or crisis and insecure contexts (World Bank 2022c). The case studies and experiences during COVID-19 exposed this challenge. For example, during COVID-19, procurement teams found it challenging to track goods because national procurement systems lack remote monitoring mechanisms. This made it difficult to know which areas of a country needed supplies, whether the supplies arrived at communities or were sitting in a warehouse, and how to coordinate the purchase of items among donors. Monitoring these outcomes would help increase the transparent and participatory engagement of beneficiaries in projects (PTF 2024).

Some projects have resolved the monitoring challenge by using new technologies or engaging third parties to monitor procurement. For example, in Bangladesh, a project used an application for the participatory monitoring of procurement. In Malawi, Nicaragua, and Paraguay, projects used georeferencing data to supervise project contracts. In Tajikistan and Zimbabwe, projects used SMS to verify that communities received project goods. Other projects have contracted third-party organizations or regional supervisors to oversee the implementation of procurement activities. For example, in a Mozambique agriculture project, provincial client representatives verified the quality of works before issuing payments to suppliers.

Procurement Reviews and Complaint Data to Help Clients Enhance Quality

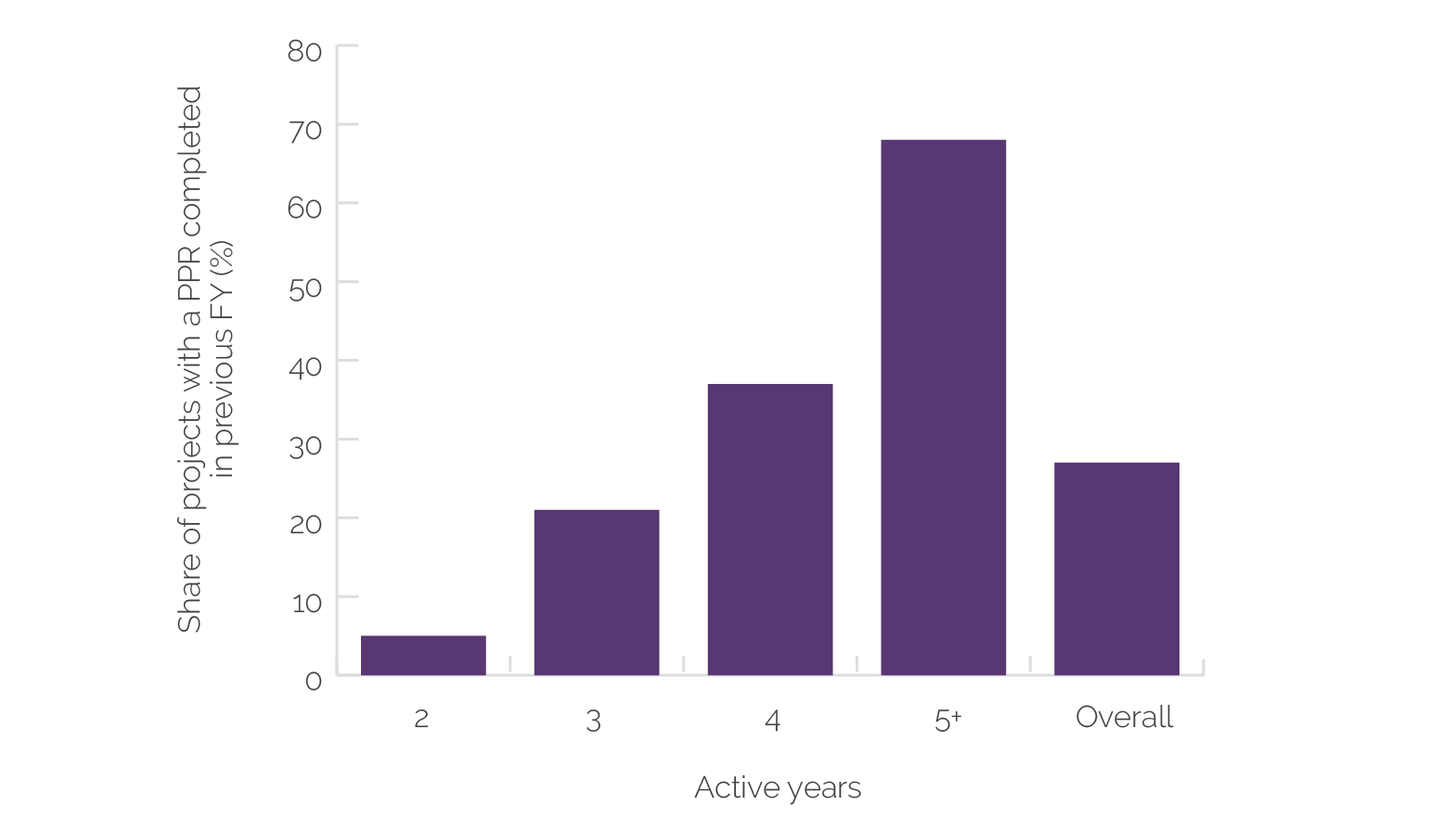

World Bank reviews of client procurement activities take place late in project implementation and are not always tailored to different project needs. Procurement post review reports (PPRs) are used to verify that clients carried out procurement activities in World Bank–supported projects in compliance with the procurement framework. However, World Bank procurement staff are often unable to complete annual PPRs, especially during the first years of implementation (figure 3.8), because projects have yet to carry out enough procurement activities to sample from or there are delays uploading data to STEP. The Governance Global Practice’s procurement reviews also report a low frequency of PPRs (World Bank 2021a). Procurement staff often take different approaches to sampling procurement activities for PPRs, leading to inconsistent audits. This is largely because the guidelines for PPRs provide flexibility in the criteria for World Bank procurement staff to make decisions on when a PPR should be done. The high flexibility limits consistent practice on when PPRs are required (World Bank 2016b). In interviews, World Bank procurement staff repeatedly note that management incentivizes them to prioritize support and reviews of high-value and high-risk activities, typically subject to prior review. TTLs emphasize the importance of greater attention in post reviews to projects at risk of having procurement issues.

Figure 3.8. Projects with Procurement Post Review Validations by Year of Project Implementation

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: The figure shows the percentage of projects with a PPR to audit procurement in the previous fiscal year by number of active years of project implementation. The total number of projects is 713. FY = fiscal year; PPR = procurement post review report.

Identifying post review procurement problems earlier could help clients improve procurement quality and avoid strained relationships between clients and the World Bank. As described in chapter 2, the higher thresholds for conducting prior reviews increase the number of procurement activities that undergo a post review, with some projects having no prior reviews at all. It also implies that clients follow World Bank post review requirements for higher-value procurement activities. In practice, this means that clients conduct increasingly more procurement activities in projects on their own without World Bank guidance, making frequent PPRs important to develop clients’ confidence and capacity to conduct procurement with minimum oversight. In addition, if World Bank staff identify serious procurement problems during the preparation of PPRs, it often strains the relationship between clients and the World Bank.

Consistent World Bank follow-up on procurement review findings could help clients avoid repeat mistakes, thereby enhancing procurement quality. Procurement validations in PPRs often document specific procurement issues, such as problems with terms of reference, shortlisting processes, or bid evaluation. However, according to the interviews, clients could benefit from more systematic follow-up to help them overcome these issues in the future. Doing so would likely make procurement implementation quicker and smoother. Instead, clients often face the same types of issues at the same stages of procurement, especially in lower-capacity contexts. Feedback from TTLs and clients in case studies emphasizes that the World Bank needs a more strategic approach to follow up with clients on the problems, especially repeat problems, identified in post reviews and to prioritize client learning and capacity strengthening.

The 2016 reform introduced a procurement pause for suppliers to submit complaints, enhancing fairness but not improving complaint handling times. Most procurement staff and TTLs agree that the standstill period provides a window for suppliers to submit complaints and for clients to systematically collect them. Nevertheless, there are trade-offs for collecting complaints without strong systems to respond and address them. The average standstill time adds about one month to procurement, and the maximum time is about four months, with some projects experiencing longer delays. The average number of complaints per project is 4, with some projects receiving 1 complaint and others as many as 19. Clients’ complaint resolution process in World Bank–supported projects remains lengthy. The average time for clients to resolve complaints in World Bank–supported projects after the reform is about 170 days (table 3.1), compared with 150 days before the reform (World Bank 2014). In some countries, clients have lengthy national complaint handling mechanisms, and supporting more agile national complaint systems could improve complaint handling times and systematically and promptly address quality issues that arise from complaints.

Table 3.1. Timelines in Days to Handle Complaints by Procurement Category

|

Procurement Category |

Mean |

Minimum |

Fast |

Median |

Slow |

Maximum |

Complaints (no.) |

|

Consulting services |

191 |

2 |

31 |

84 |

225 |

1,449 |

283 |

|

Works |

163 |

3 |

26 |

65 |

154 |

1,209 |

203 |

|

Nonconsulting services |

104 |

3 |

18 |

63 |

83 |

853 |

56 |

|

Goods |

177 |

0 |

27 |

83 |

212 |

1,450 |

227 |

|

Overall |

173 |

0 |

28 |

75 |

189 |

1,450 |

769 |

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: “Fast” refers to the bottom 25 percent of projects, and “slow” refers to the top 75 percent of projects. Timeline is in days. The total number of complaints in 240 projects with complaint timeliness information available is 769.

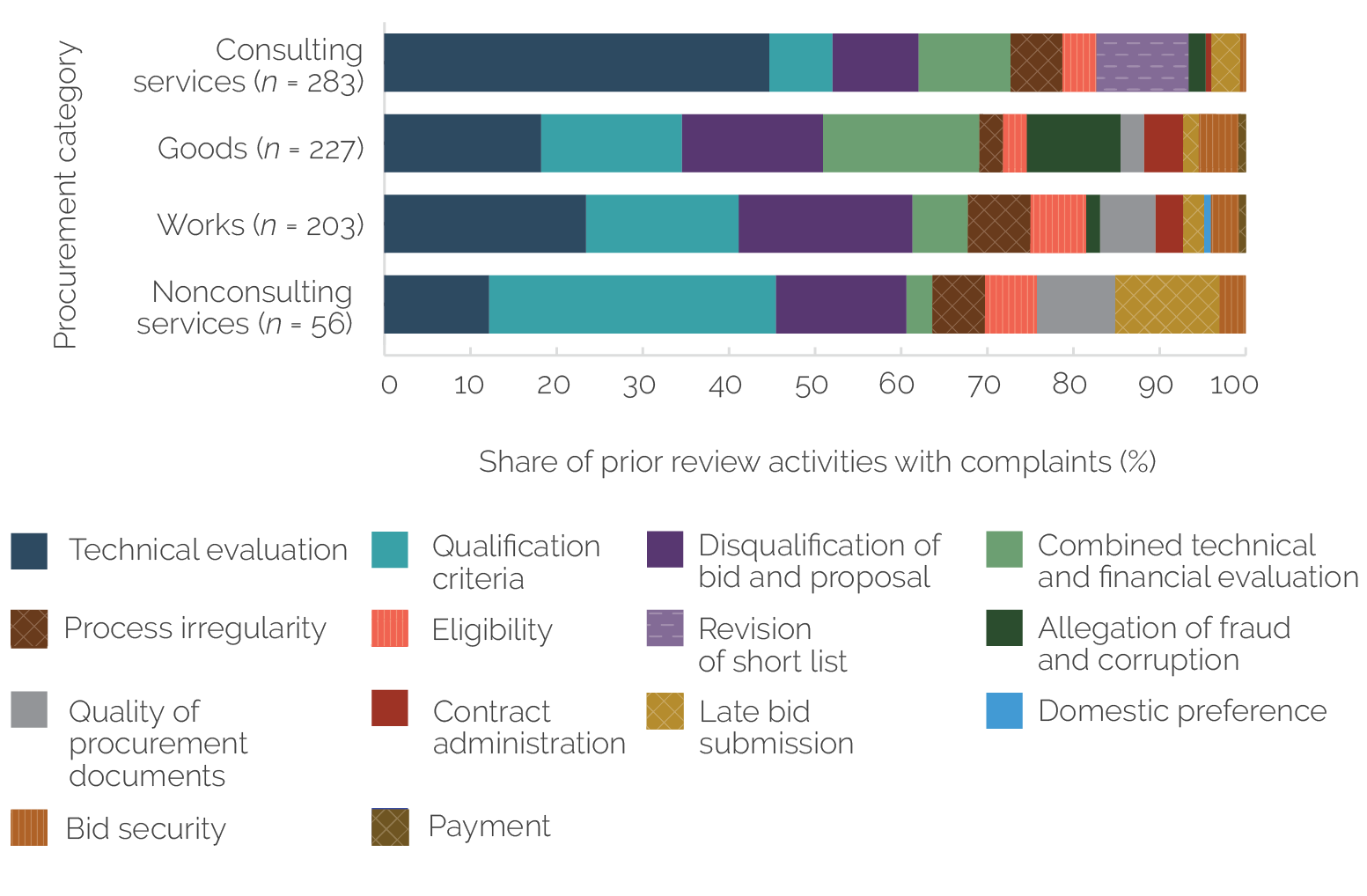

The World Bank could support clients in using complaint information to systematically improve procurement quality. The World Bank and clients make limited use of complaint data to improve procurement quality. Repeat complaints often involve procurement quality challenges, such as weaknesses related to technical evaluations or disqualification of bids (figure 3.9). Studies suggest that procurement complaints can be a tool to strengthen national systems (Hargreaves 2022). However, the review of country procurement capacity strengthening portfolios shows that it is rare that World Bank country programs use this information to improve procurement. This suggests that strengthening clients’ capacity to overcome repeat systemic problems raised in complaints would improve procurement quality.

Figure 3.9. Complaints by Type in World Bank–Supported Prior Review Procurement

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: The figure shows the share of prior review activities with complaints, by nature of the complaint, recorded in the Systematic Tracking of Exchanges in Procurement system. The total number of complaints in 240 projects is 769.

- Market approaches include direct selection, which identifies a supplier or consultant without competition from a preidentified candidate. Limited selection invites preidentified qualified suppliers to bid on a procurement (which allows for competition). The open, competitive approach provides qualified suppliers or contractors in the market the opportunity to submit their proposals through a public tender. Market approaches also consider whether a procurement is international, to attract suppliers outside of a country, or national, for suppliers in the country (World Bank 2020b).

- Rated criteria can be combined with procurement methods to assess quality and other nonprice features for decisions on the award of the contract. Competitive dialogue is an interactive engagement with potential suppliers of a proposal to optimize the details of the work to the project context (World Bank 2020b).

- Negotiation can help the client in an iterative two-way communication, with the potential supplier bidding on the contract and focusing on improving various aspects of the bid or proposal. Negotiations could involve technical aspects of the design, cost, or other aspects. Best and final offer is a process enabling potential suppliers to improve their bid or proposal, including by reducing prices, clarifying or modifying details, or providing additional information. It can be helpful if there are multiple, similar competitive bids (World Bank 2020b).

- The analysis focuses on requests for proposals and requests for bids that are prioritized for rated criteria use. The rate is higher in international contracts than national contracts.

- Contract management was only marginally examined in the evaluation because the World Bank’s contract management system was broadly rolled out in 2023. This system is likely to face issues similar to those observed with the Systematic Tracking of Exchanges in Procurement system, especially in terms of clients’ burden and the completeness and quality of data.