International Finance Corporation Additionality in Middle-Income Countries

Chapter 1 | Introduction

Highlights

Additionality is the unique contribution—not offered by commercial sources of finance—that a development finance institution, such as the International Finance Corporation, brings to a private investment project. It comprises financial and nonfinancial additionality.

Financial additionality includes features such as the financing structure (for example, loan tenor, local currency loans) and innovative financing (for example, derivatives, green bonds). Nonfinancial additionality encompasses other unique contributions such as the deployment of knowledge and standards.

Additionality is different from, but contributes to, development impact. It varies by country, sector, market, and client characteristics.

Proper articulation of additionality is especially important in middle-income countries, where private investment is much more common than official development assistance and where financial sectors are more developed.

This evaluation examines the relevance and effectiveness of the International Finance Corporation’s approach to additionality in middle-income countries. This includes not only attention to project-level additionality but also—for the purpose of learning—consideration of additionality at the country and sector levels. From the evaluation, we derive lessons on how the International Finance Corporation can further strengthen its additionality.

The findings are based on mixed methods, including portfolio review and analysis, country case studies, statistical and econometric analysis, a structured literature review, semistructured interviews of experts, and deep dive input papers.

Definition and Nature of Additionality

The International Finance Corporation (IFC) defines additionality as the unique contribution that it brings to a private investment project that is typically not offered by commercial sources of finance (IFC 2019b). Development finance institutions (DFIs), such as IFC, play a critical role in supporting the development and growth of markets and private sector investment in low-income countries (LICs) and middle-income countries (MICs).1 To avoid crowding out (displacing) the private sector, IFC’s and other DFIs’ investments have to provide unique value to clients, offering features not available from commercial sources of finance. IFC’s unique value is rooted in its comparative advantage over the private sector in bridging the gap between private and public sectors, leveraging its global expertise and knowledge, investing in markets perceived as too risky for the private sector, and taking a longer-term view than other investors (IFC 2019b).

The concept of additionality can be traced back to IFC’s Articles of Agreement and is articulated for all the major multilateral development banks (MDBs). The concept of adding to and not displacing private financing is outlined in IFC’s Articles of Agreement, which state that “the Corporation shall not undertake any financing for which in its opinion sufficient private capital could be obtained on reasonable terms” (IFC 2020). The concept of additionality is most clearly articulated for all the major MDBs in the Multilateral Development Banks’ Harmonized Framework for Additionality in Private Sector Operations (the Harmonized Framework). In response to demand from stakeholders, IFC joined 10 other prominent MDBs to adopt this Harmonized Framework in 2018 (AfDB et al. 2018). The Harmonized Framework provides a common definition of additionality, requiring that “interventions by [MDBs] to support private sector operations should make a contribution beyond what is available in the market and should not crowd out the private sector” (AfDB et al. 2018, 3). IFC’s Revised Additionality Framework is fully aligned with the MDBs’ Harmonized Framework, while aiming to introduce more rigor to IFC’s assessments of additionality (IFC 2019b). This framework, with its detailed typology and guidance, is consistent with prior IFC practice, enhancing the definitions and guidance IFC already had in place.

Additionality contributes to achieving development impact. IFC’s Revised Additionality Framework acknowledges a direct link between additionality and development impact. It states that additionality is essential for delivering development impact that would not have happened without IFC’s involvement (IFC 2019b). The link can be direct, for instance when IFC helps the client reduce emissions by introducing environmental standards, or indirect, when IFC’s additionality reduces a project’s risk profile and contributes to the likelihood of the development outcomes materializing.

Furthermore, the Sustainable Development Goals require DFIs to support private investment in a unique way. DFI additionality may be delivered, for example, by creating the market conditions for the private sector to invest (through noncommercial risk mitigation, a feature of nonfinancial additionality) or by mobilizing private capital (a feature of financial additionality). The unique support provided to the private sector is critical to allow DFIs to contribute to the objective of increasing development assistance from “billions to trillions” (AfDB et al. 2015). Examples of Sustainable Development Goals for which DFIs’ additional support to the private sector is vital include combating climate change, building infrastructure, fostering innovation, and enabling access to energy.

There are two types of additionality: financial and nonfinancial. Financial additionality is based on the features of the financial package offered by IFC, including the financing structure (such as longer tenors and provision of local currency financing), resource mobilization (from the private sector or other DFIs), or innovative financing (such as derivatives and green bonds). Nonfinancial additionality relates to the deployment of knowledge and standards—for example, mitigation of noncommercial risks, such as country or project risks, or provision of expertise in environmental and social (E&S) standards or industrial standards that are material to improve development impact. A single project can anticipate more than one form of additionality—for example, by IFC offering both long tenor and resource mobilization. See table 1.1.

Table 1.1. Types of Additionality

|

Type |

Subtype |

Description |

|

Financial additionality |

||

|

1. Financing structure |

Amount of financing provided, tenors and grace periods, provision of local currency financing |

|

|

2. Innovative financing structure and/or instruments |

Includes financing structures not available in the market that add value by lowering the cost of capital or better addressing risks (such as trade finance, derivative products, green bonds, or securitizations) |

|

|

3. Resource mobilization |

IFC’s verifiable role in mobilizing commercial financing from an institutional or private financier that would be delayed, reduced, or unlikely in the absence of IFC involvement |

|

|

4. IFC’s own account equity |

IFC provides equity unavailable in the market in a way that strengthens the financial soundness, creditworthiness, and governance of the client. |

|

|

Nonfinancial additionality |

||

|

1. Noncommercial risk mitigation, including trusted partnerships |

IFC provides comfort to clients and investors by mitigating noncommercial nonenvironmental and social risks, such as country, regulatory, project, or political risks, while adhering to IFC’s principle of political neutrality. |

|

|

2. Frameworks: catalyzing policy or regulatory change |

IFC’s involvement in a project catalyzes the investment response to changes in the policy/regulatory framework. The project is the first to test a new or untested policy, regulatory regime, or legal framework/PPP model. IFC’s involvement is also likely to mitigate further regulatory changes or other risks to the project. |

|

|

3. Knowledge, innovation, and capacity building |

IFC plays a verifiable, active, and direct role in providing expertise, innovation, knowledge, and/or capabilities that are material to the project’s development impact due to the perceived weak institutional capacity of the borrower or investee. |

|

|

4. Standard setting |

IFC is a provider of expertise in environmental and social standards, corporate governance, insurance, and gender, and is additional where the laws and market practice do not reinforce this behavior. Changes in practices have to be significant enough to matter from a development impact angle: they have to pass the “so what” test. |

|

Source: International Finance Corporation 2019b.

Note: IFC = International Finance Corporation; PPP = public-private partnership.

In IFC, documenting anticipated additionality is a condition for project approval. In IFC and many other DFIs, anticipated additionality is a condition for approval of potential private investment projects, along with strategic relevance, development impact, sustainability, and financial viability (IFC 2019b). Additionality types and combinations vary by country income, sector, market and clients, all of which evolve over time (AfDB et al. 2018). Yet for project approval, additionality is either present or not present—IFC and most DFIs do not rate its strength nor adapt their additionality requirements by context. The European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) is an exception in this respect, as it does scale its evidence of additionality to context, by using triggers to identify cases where additionality requires enhanced scrutiny and evidence (box 1.1).

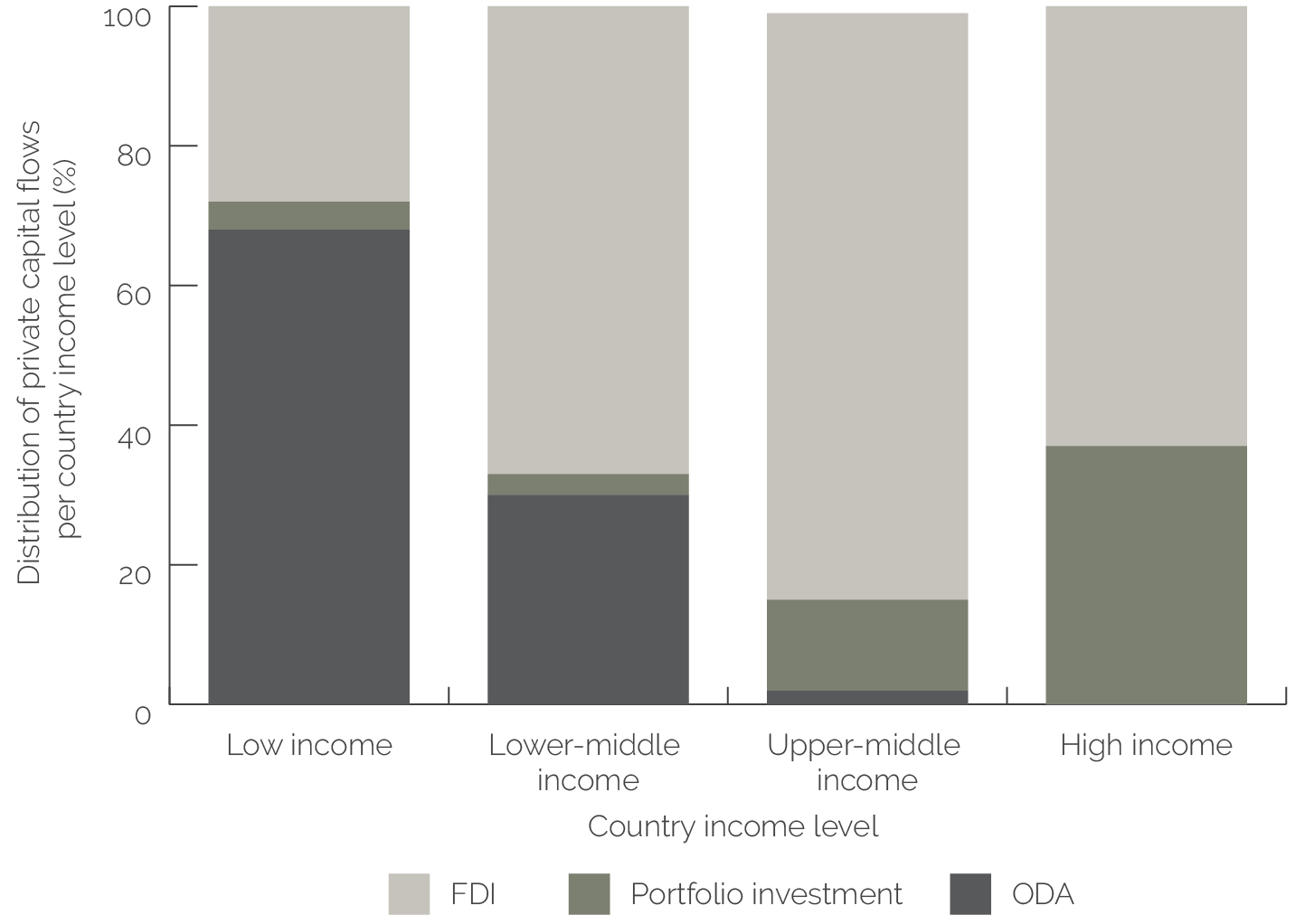

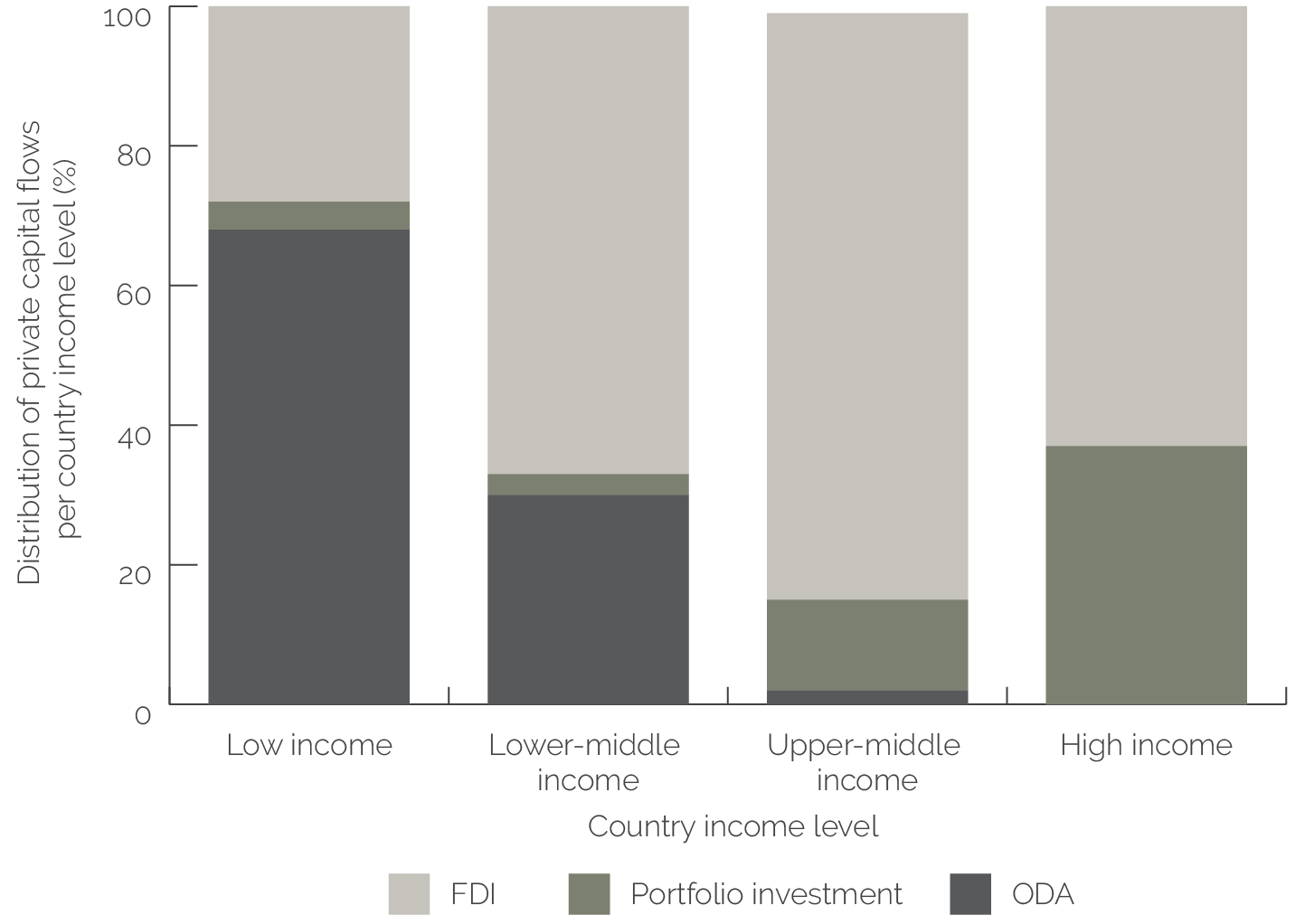

Proper identification of additionality is particularly important in MICs because of the higher availability of private capital in these countries relative to LICs. It is well recognized that global challenges embodied in the Sustainable Development Goals will require substantial progress in MICs, especially on issues related to poverty, inclusion, and the environment. Proper identification of additionality ensures that DFIs’ activities in these markets do not displace private financing, which is increasingly available in MICs. Private capital flows to developing countries have grown over time, and private investment is prominent in both lower-middle-income countries (LMICs) and upper-middle-income countries (UMICs), with volumes of official development assistance being negligible in UMICs (figure 1.1). The detailed dimensions of additionality established in IFC’s framework help it identify cases where, in financial or nonfinancial dimensions, it can contribute to development beyond what available private finance can do. If additionality is not present, there is a real danger of crowding out the private sector. Thus, assessing IFC’s additionality in MICs and identifying lessons to increase it are vital.

Box 1.1. Sufficient Additionality: The Approach of the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development

For the International Finance Corporation, as for most other development finance institutions, additionality is a condition for approval of potential private investment projects and is considered either present or not present. This binary approach to additionality works most times. In some instances, however, discussions arise about whether the additionality presented is “sufficient” to justify the International Finance Corporation’s engagements, for example, with a strong repeat client or in an upper-middle-income country with a well-developed financial sector.

The European Bank for Reconstruction and Development tries to address this issue by applying a “triggers” system, by which stronger additionality evidence is required in potentially contentious cases where additionality appears weak. The triggers are related to the type of client, type of financing, and use of proceeds, among others.

For instance, projects with strong clients that are better able to find good financing terms (or rely on a parent for funds) or to access international capital markets more easily than other market players will trigger the requirement for a stronger articulation of additionality.

Although the International Finance Corporation implicitly follows a similar approach by providing a more thorough additionality rationale for some projects (for example, a project in an upper-middle-income country with a repeat client), the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development has an explicit procedure which introduces greater clarity on the circumstances under which teams should strengthen a project’s additionality rationale.

Source: Independent Evaluation Group (see appendix F).

Figure 1.1. Private Capital Flows per Country Income Level

Source: World Development Indicators database 2018 (https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators).

Note: FDI = foreign direct investment; ODA = official development assistance.

Evaluation Questions

The evaluation investigates the relevance and effectiveness of IFC’s approach to additionality in MICs.

The evaluation seeks to answer three questions:

1.Relevance. To what extent does IFC’s anticipated additionality vary, and what explains variance according to country and industry or sector conditions in LMICs and UMICs, IFC instruments and platforms, and the presence and role of other providers of finance and services in the same industry, sector, or country?

2.Effectiveness. To what extent was IFC’s anticipated financial and nonfinancial additionality actually realized in LMICs and UMICs, and to what extent was it plausibly linked to enhanced development outcomes and impact at the project, industry or sector, and country level?

3.Learning. How can IFC strengthen its additionality at the country, industry or sector, and project or instrument level?

As is reflected in the questions, the evaluation distinguishes between anticipated and realized additionality. At the outset of a project, when it is being designed and appraised, IFC identifies the additionality it believes will be associated with its support. This is the project’s anticipated additionality. Once a project is terminated, it may be evaluated to determine whether the anticipated additionality actually occurred—that is, whether IFC delivered a unique contribution to the client or partner consistent with its expectation. This is realized additionality.

Methods

The evaluation applied mixed methods. The evaluation applied a combination of methods that provide qualitative and quantitative evidence to answer the evaluation questions. The use of mixed methods supported triangulation of findings from multiple sources to enhance their robustness. The main methods included the following:

- Portfolio review and analysis (PRA) of evaluated and nonevaluated investment services (IS) projects (table 1.2). The Independent Evaluation Group (IEG) conducted a PRA of the anticipated and realized additionality of 579 IFC IS evaluated during fiscal years (FY)11–21 and an analysis of success factors. IEG also conducted a PRA on the treatment of anticipated additionality in a representative sample of 95 unevaluated investment projects approved during FY11–21. IEG could not apply a parallel approach to analyzing advisory services (AS) projects because of shortcomings in additionality information in IFC AS documents.

Table 1.2. Summary of Identified International Finance Corporation Portfolio

|

Country Cases |

Approved FY11–21a |

Evaluated FY11–21 |

|||||||||

|

Projects |

Volumeb |

Projects |

Volumeb |

||||||||

|

(no.) |

(%) |

(US$, millions) |

(%) |

(no.) |

(%) |

(US$, millions) |

(%) |

||||

|

IFC IS |

2,400 |

100 |

97,966 |

100 |

661 |

100 |

22,395 |

100 |

|||

|

Country casesc |

811 |

34 |

38,572 |

39 |

227 |

34 |

8,232 |

37 |

|||

|

Noncountry cases |

1,589 |

66 |

59,394 |

61 |

434 |

66 |

14,163 |

63 |

|||

|

IFC AS |

1,010 |

100 |

1,524 |

100 |

414 |

100 |

539 |

100 |

|||

|

Country casesc |

204 |

20 |

311 |

20 |

92 |

22 |

148 |

28 |

|||

|

Noncountry cases |

806 |

80 |

1,213 |

80 |

322 |

78 |

390 |

72 |

|||

|

MICs |

3,410 |

100 |

99,489 |

100 |

1,075 |

100 |

22,934 |

100 |

|||

|

Country casesc |

1,015 |

30 |

38,883 |

39 |

319 |

30 |

8,381 |

37 |

|||

|

Noncountry cases |

2,395 |

70 |

60,606 |

61 |

756 |

70 |

14,553 |

63 |

|||

Source: Independent Evaluation Group portfolio review and analysis.

Note: Totals may not add up because of rounding. AS = advisory services; FY = fiscal year; IFC = International Finance Corporation; IS = investment services; MIC = middle-income country. a. Excludes rights issues, swaps, B-loan increase, risk management, agency master, and restructuring. b. For IS projects, it consists of IFC’s commitment at approval; for AS projects, it consists of total funds managed by IFC. c. Includes projects from Nigeria and Bangladesh approved or evaluated between 2011 and 2021, when they were still low-income countries.

- Country case studies. IEG conducted nine case studies in select countries: Bangladesh, China, Colombia, the Arab Republic of Egypt, Indonesia, Mexico, Nigeria, South Africa, and Türkiye. The selection reflected diverse country conditions, including income level (UMIC and LMIC), region, and fragility. Country selection also considered the size of the portfolio and the representativeness and comparability of sectors. For focus and comparability purposes, in each country case study, two sectors were chosen as areas of interest. The sectors were commercial banking, microfinance and chemical and fertilizers (assessed in four countries), and electric power (assessed in five countries). Case studies involved both desk-based research and field assessments (mostly remote) that interviewed IFC staff, clients, governments, and other organizations (DFIs and others) that offer similar services and products.

- Statistical and econometric analysis. The analysis used PRA data and other indicators to relate the successful realization of financial and nonfinancial additionality to a variety of explanatory factors, including work quality.

- Structured literature review on additionality. The evaluation explored the very limited available literature on donor financial and nonfinancial additionality in the private sector, including on links between additionality and development outcomes and donor financial sustainability.

- Semistructured interviews of experts. IEG interviewed 21 IFC staff with expert knowledge of additionality. The interviews discussed, among other topics, aspects of IFC’s additionality and related practices beyond what is reflected in corporate documents, its use of additionality as a decision-making tool, the differences between additionality in LMICs and UMICs, and identification of best practices and challenges.

- Deep dive input papers. The evaluation team produced in-depth papers on (i) DFIs’ additionality in MICs and (ii) additionality features of IFC’s financing instruments in MICs.

The evaluation focuses on assessing additionality at the project level but also applies country and sector lenses for learning purposes to explore achievement of additionality beyond the project level. The main focus of the evaluation is on examining additionality at the project level, consistent with IFC’s commitment to achieve additionality at this level. However, as agreed with IFC management at the Approach Paper phase, the relevance of the country and sector lens can provide valuable learning and reveal where and how IFC’s additionality transcended the project level, thus influencing sectors’ or countries’ development.

The remainder of this report is organized into four chapters that aim to address the evaluation questions.

- Chapter 2 addresses question 1 on the relevance of additionality. It first describes anticipated additionality at the project level and how additionality varies depending on country income level, sector, and IFC’s financing instruments. For learning purposes, the chapter then presents a discussion of anticipated additionality that goes beyond the project level and speaks to the value that IFC may add in a sector in a given country (referred to as “country sector”).

- Chapter 3 addresses question 2 on the effectiveness of IFC additionality. First, it analyzes the extent to which IFC is realizing anticipated financial and nonfinancial additionality in MICs. Second, it assesses the extent to which the additionality IFC is realizing plausibly contributes to enhanced project development outcomes. Finally, it applies the country and sector lenses to learn about where and when the additionality of IFC’s overall activities in a sector or country adds up to something greater than the value added by each individual project.

- Chapter 4 presents evidence and findings on the factors that help explain both cases in which IFC realized additionality and cases in which it did not. It considers internal explanatory factors that IFC can directly control and external factors, some of which IFC may not be able to influence. It then applies the country and sector lens to consider factors influencing additionality that transcend the level of individual projects.

- Chapter 5 discusses IEG recommendations to enhance IFC’s additionality, based on the analysis of the preceding chapters.

Limitations

The evaluation follows the definition and additionality types presented in IFC’s additionality framework. It does not consider types of additionalities that are not present in the framework, nor is it an evaluation of the framework itself. In addition, although the evaluation considers the relationship of additionality to development effectiveness, it is not an evaluation of IFC’s development effectiveness. Further, IEG was unable to consider the additionality of AS projects, because IFC did not consistently identify and evaluate AS project additionality over the evaluation period. Furthermore, because IFC’s Revised Additionality Framework was activated only in FY19, there were virtually no evaluated projects approved under the new framework. Trends can be observed in anticipated additionality through project documents and interviews with well-informed observers, but project evaluations do not include information about realized additionality in the recent period. Although the evaluation conducted an analysis of anticipated additionalities in a sample of the unevaluated portfolio, its results are not conclusive given the sample size. In addition, although IEG considers additionality through sector and country lenses for learning purposes, as agreed at the Approach Paper stage, it does not aggregate additionality above the project level. Next, this evaluation focuses on IFC’s work in MICs. IFC’s work in LICs is outside its scope; the evaluation does not explicitly compare IFC’s work in MICs to its work in LICs. Finally, country case studies were designed to focus on a limited number of sectors for comparability and critical mass of observation. It is recognized that other sectors in which IFC may have been highly additional were not analyzed.

- The term development finance institutions encompasses bilateral and multilateral donors. The term multilateral development banks refers exclusively to multilateral finance institutions such as the Asian Development Bank, the Inter-American Development Bank, the European Investment Bank, and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, among others. Bilateral donors include agencies such as Norfund and British International Investment.