World Bank Group Gender Strategy Mid-Term Review

Chapter 2 | Commitment to the Strategic Objectives

The gender strategy outlines an approach that intends to translate Bank Group commitments on closing gender gaps into demonstrable results. Interviews, data, and documents demonstrating the strategic objectives of the gender strategy have received ongoing and well-documented commitment from management and development partners, a precondition for success. The organizational commitment to the strategy has translated into updated project design, as demonstrated by increased gender tagging and flagging. Further translation of organizational commitment to project implementation is constrained by the lack of familiarity with a gender gap approach among task team leaders, project leads, investment officers, and practice managers.

Management and Development Partner Commitment

The objectives of the strategy have received development partner commitment. Two development partners interviewed for the review were supportive of the strategy and its potential to help identify, address, and close gender gaps across sectors. Representatives of the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency and Global Affairs Canada said the gender strategy has high global visibility; stakeholders, they said, are on board with its potential. International commitment to the objectives of the strategy is further demonstrated by the incorporation of gender gaps into International Development Association (IDA) replenishments and Bank Group capital package proposals. The commitments noticeably evolved from a focus on improving Bank Group processes in the 16th Replenishment of IDA (IDA16) and IDA17 to outcome-focused gender gap targets in IDA18, IDA19, and the capital package after the introduction of the strategy. These commitments are further described in box 2.1.

Box 2.1. International Development Association and Capital Replenishment Commitments That Reinforce the Gender Strategy

Commitments agreed on by International Development Association (IDA) shareholders during the Replenishment process demonstrate the World Bank Group’s enhanced focus on gender gaps and international commitment. The focus of commitments on gender has shifted from improving internal processes to closing gender gaps.

IDA16 and IDA17 Replenishments

The IDA16 and IDA17 commitments supported the development of the World Bank’s approach to gender. These commitments focused on knowledge and processes, including the following:

- Making the case in the World Development Report 2012 that investing in women and girls is smart economics (World Bank 2011).

- Implementing and deepening the integration of gender into World Bank action plans for Regions and countries, and in the reproductive health and education sectors.

- Strengthening results frameworks that incorporate gender mainstreaming by including indicators at the country level and for operational efforts.

- Intensifying capacity-building efforts through experiential learning.

IDA18 and IDA19 Replenishments

The commitments for IDA18 and IDA19 shifted to focus on the following:

- Closing first-generation gaps in human endowments, specifically in primary and secondary education and reproductive health.

- Removing constraints for more and better jobs through developing skills, reducing occupational segregation, and addressing mobility and security needs in urban passenger transport.

- Increasing women’s financial inclusion and entrepreneurship through improving access to and use of financial services and land, reporting on financial inclusion, and supporting better participation in the digital economy and information and communications technologies.

- Enhancing women’s voice and agency, engaging men to respond to gender-based violence, and implementing a global task force on gender-based violence.

- Enabling country-level action through data collection, ensuring at least basic availability of gender data and knowledge for all IDA countries through a core data package, and encouraging further investments in “what works.”

In the Bank Group capital package, the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development and the International Finance Corporation made commitments to meaningfully narrow gender gaps.

- International Bank for Reconstruction and Development: Increasing the proportion of its operations that close gender gaps and taking specific actions to close gender gaps in the access to and use of financial services by fiscal year 2023 with ambition maintained or increasing to fiscal year 2030.

- International Finance Corporation: By 2030, quadrupling the amount of annual financing dedicated to women and women-led small and medium enterprises, increasing annual commitments to financial intermediaries targeting women, and doubling the share of women directors that it nominates to boards of companies; by 2020, flagging all projects with gender components.

In the Mid-Term Review of IDA18, all targets were reported to be on track, though implementation challenges were noted in filling data gaps and in identifying and working on the highest-impact interventions in key focus areas, for example. IDA19 also sought to build interconnections with the other IDA special themes of fragility, conflict, and violence; jobs and economic transformation; and governance and institutions.

Source: World Bank 2010b, 2013, 2017c, 2020.

Development partners also confirmed strong recognition of knowledge developed by the Bank Group on gender gaps. The interviewees identified the Bank Group as producing and contributing to important research in support of gender equality, which they used to inform their own positions. The development partners also identified World Bank products that they built on in their own work, such as the report Unrealized Potential: The High Cost of Gender Inequality in Earnings (Wodon and de la Brière 2018); the sector report The Rising Tide—A New Look at Water and Gender (Das 2017); and the Women Business and the Law project and data set, which has expanded over time and analyzes laws and regulations affecting women’s economic inclusion in 190 countries. The interviewees from the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency and Global Affairs Canada also cited valuable IFC products and initiatives,1 such as Energy2Equal, through which IFC is working with large and small companies across Sub-Saharan Africa to close gender gaps and increase women’s participation in the renewable energy sector. They also mentioned Driving toward Equality: Women, Ride-Hailing, and the Sharing Economy (IFC and Uber 2018), which explores how women and men participate in ride-hailing, particularly in emerging markets, as well as more specific work, such as the IFC (2017) case study Gender-Smart Solutions Reduce Employee Absenteeism and Turnover in Solomon Islands.

Management across senior levels of the World Bank and IFC demonstrates commitment to the gender strategy and pushes relevant concepts and practices downward.2 IEG found strong commitment to the strategy among vice presidents and senior management in the World Bank and IFC. In interviews and focus groups, staff confirmed that top management across the institutions supports the aims of the strategy. This is also true of World Bank and IFC management at the regional level, in Global Practices, and in industry groups. For example, when RGAPs are discussed during periodic updates, staff reported evident ownership, learning, and commitment from management. IFC regional directors and industry managers we interviewed saw the strategic potential in closing gender gaps for developing new business lines. Senior management further demonstrated commitment through conspicuous and explicit support for the strategy in speeches, articles, and blogs.3

There was widespread support of the strategic focus on the four key outcomes in human endowments, jobs, asset control and ownership, and voice and agency among Bank Group management. Several vice presidents, regional directors, and country directors mentioned that their policy dialogue with governments and the private sector on gender has become much more effective since they have been able to show data linking persistent gender gaps with hindered economic growth, rather than the more general discussions they had under the gender mainstreaming approach (box 2.2). A few senior staff cautioned that the gender gap analysis may push teams toward human endowments, where the gender differences are apparent and data are more available, compared with voice and agency.

Box 2.2. Gender Mainstreaming and Gender Gap Approaches

Gender mainstreaming is the process of assessing the implications for women and men of any planned action, including legislation, policies, or programs, in all areas and at all levels. It is a strategy for making women’s and men’s concerns and experiences an integral dimension of the design, implementation, monitoring, and evaluation of policies and programs in all political, economic, and societal spheres so that women and men benefit equally, and inequality is not perpetuated.

A gender gap approach promoted in the World Bank Group Gender Strategy seeks to address specific disparities using diagnostics and analytics to identify gaps between men and women in a country or sector that can then be targeted through operations to achieve clearly articulated results.

Source: Cited in United Nations Economic and Social Council 2018; Adapted from IFC, forthcoming a; World Bank 2015d, 2019b.

Operational Commitment

World Bank and IFC operational staff who participated in IEG interviews and focus groups expressed their personal and professional commitment to the principle of addressing gender disparities. Staff in both institutions appreciated the value of closing gender gaps, but not necessarily because they were familiar with the strategy document. They understood that the development cost of not addressing gender gaps is high and that the approach offered opportunities to develop new business with clients. IFC staff appreciated the gender community of practice that helped develop their understanding of the corporate commitment to deliver gender outcomes.

In both IFC and the World Bank, increasing percentages of projects have received the gender tag or flag based on data supplied by their reporting systems. The gender tags of the World Bank and the gender flags of IFC assess the results chains of projects by identifying whether their design has analyzed a gender gap, developed an activity to respond to the gap, and put gender gap indicators in results frameworks. Gender tags are validated by the Gender Group of the World Bank after the Board approves the operation. Gender flags are self-assigned by IFC staff, with review, advice, support, and training, but not validation, from the GBG.4 To provide further assurance, IFC could revisit the quality control processes of flagging, for example by reviewing a random sample of flagged projects to quantify the extent to which self-assigned flagging diverges from the guidance.

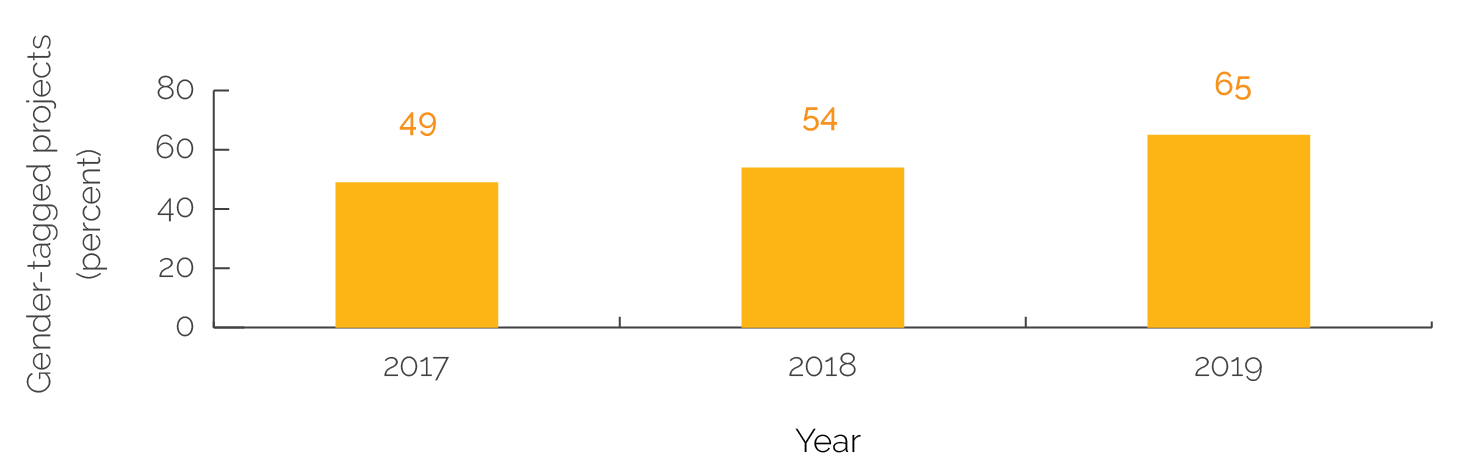

In the World Bank, 65 percent of all operations approved in FY19 were designed with the intention to close gender gaps (figure 2.1). Before the implementation of the gender strategy, an IEG review found that only 24 percent of World Bank projects that closed between FY12 and FY14 had applied a gender lens in analysis, action, and monitoring (World Bank 2016). In contrast, during the strategy period between FY17 and FY19, the number of projects that received the tag increased by 16 percentage points (49 to 65 percent). The corporate target for gender-tagged projects is currently 55 percent for World Bank, IDA, and International Bank for Reconstruction and Development projects, except for International Bank for Reconstruction and Development operations that seek to narrow gaps in access to financial services, whose target is 60 percent. In FY19, all Regions met or exceeded this target. Of the 573 gender-tagged projects between FY17 and FY19, 478 (83 percent) were investment projects. Across the three-year period, the prevalence of gender tagging was greater in IDA (59 percent) and in fragile and conflict-affected situation (FCS) countries (59 percent) than in International Bank for Reconstruction and Development and non-FCS countries.

Figure 2.1. World Bank Gender-Tagged Projects out of All Lending, FY17–19

Source: World Bank gender tag data.

Note: FY = fiscal year.

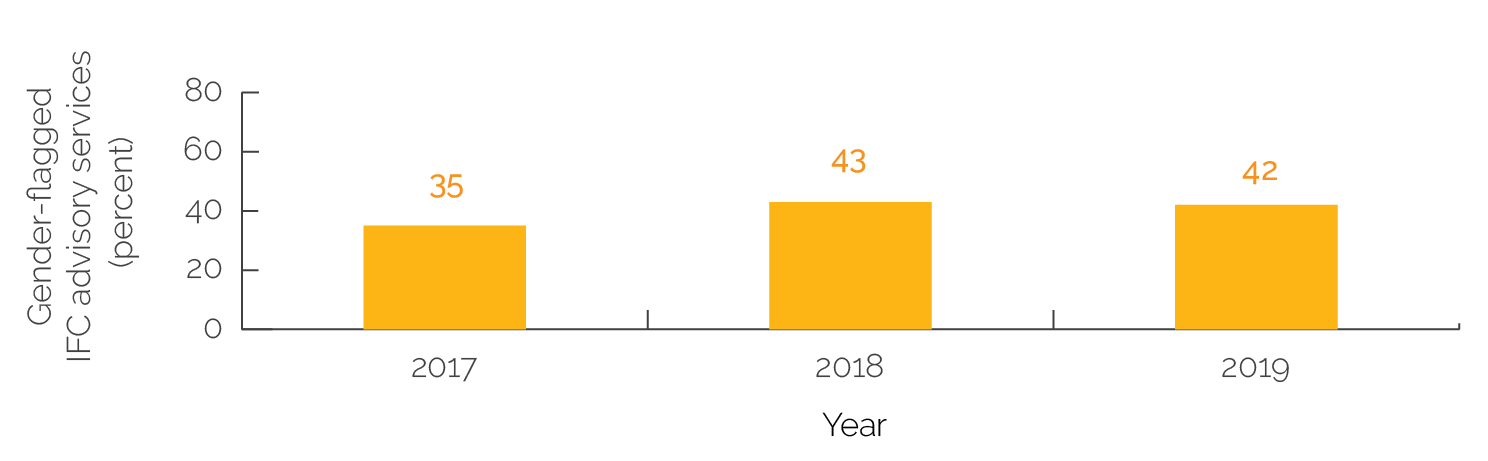

Within the IFC portfolio, advisory services (AS), which were required to be gender flagged throughout the period this review examined, increased from 35 percent in FY17 to 42 percent in FY19. The corporate target for gender-flagged AS projects of 40 percent was exceeded in both FY18 and FY19. Sub-Saharan Africa and global programs contributed the most to exceeding this target in FY19, with all other regions falling below the target. For FY17–19, 185 AS projects are flagged, only 27 of which are in FCS countries (15 percent; figure 2.2). IDA countries account for the majority of tagged AS projects (117; 63 percent).

Figure 2.2. Gender-Flagged IFC Advisory Services out of All IFC Advisory Services, FY17–19

Source: International Finance Corporation gender flag data.

Note: FY = fiscal year; IFC = International Finance Corporation.

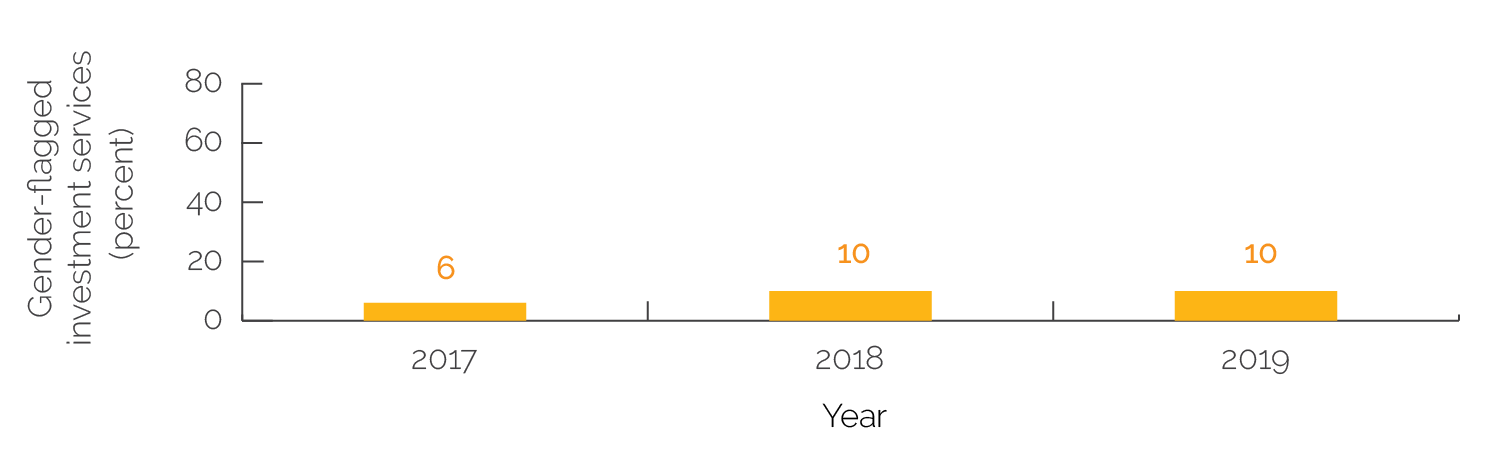

IFC investment services (IS) have a lower proportion of projects that address gender gaps than AS, with the amount flagged increasing from 5 percent in FY17 to 10 percent in FY19. Initially, the flagging of IS projects was voluntary in 2017, and it was only made mandatory in December 2018 to meet the Bank Group capital package commitment. Consequently, 38 percent of the IS projects approved for FY17 and FY18 did not record whether they addressed gender gaps. For the purposes of corporate reporting and this review, projects that did not report on the gender flag are treated as not having addressed gender gaps. Between FY17 and FY19, 66 out of 773 IS projects were flagged as addressing gaps (figure 2.3). The largest proportion of these projects was in Sub-Saharan Africa, which accounted for just over a third (23). Of the gender-flagged projects, 8 were in FCS countries and 25 in IDA countries. Just under two-thirds of the gender-flagged investments were in the Financial Institutions Group (FIG), a topic discussed further below.

Figure 2.3. Gender-Flagged IFC Investment Services out of All IFC Investment Services, FY17–19

Source: International Finance Corporation gender flag data.

Note: FY = fiscal year; IFC = International Finance Corporation.

Task team leaders, staff designated to support work on gender, and practice managers reported that the tag process in the World Bank absorbs significant time and effort given the shift from mainstreaming to gap analysis and a rigorous validation process. In the first half of the strategy, the tag process has emphasized applying the gap analysis across Global Practice portfolios, which has helped smooth the shift from mainstreaming. For example, multiple Global Practice gender experts and focal points reported that all their allotted time has gone to advising on tagging processes, which has limited their ability to assist teams during implementation. Practice managers and task team leaders across Regions overwhelmingly believed that corporate targets (currently 55 percent) permit the strategic use of human resources and that 100-percent targets led to “force-fitting” gender gaps within operations. Force-fitting of gender gaps was not reported in IFC, where there were no reported pressures to meet additional higher targets. Chapter 5, meanwhile, provides evidence that the Bank Group needs to place more emphasis on the monitoring and evaluation of implementation to close gender gaps.

The strategy aims for gender gaps to be part of every phase of the project cycle, yet staff, outside of those with gender expertise, are still insufficiently familiar with the gender gap approach. Interviews highlighted that the Bank Group lacks a requirement for gender awareness development among staff; in a minority of instances, this missing requirement was reported to lead to gender issues being deemed irrelevant. IFC and World Bank gender groups have each implemented focused training on gender tagging and flagging, and supported the development of guidance notes, a variety of reports, and information sessions to raise the awareness of staff. IFC also has an e-learning training on gender gaps. Stand-alone e-learning for the World Bank that would improve knowledge on gender gaps has been developed in 4 of 15 Global Practices—Agriculture, Environment and Natural Resources, Energy, and Social Sustainability and Inclusion. Although these efforts were very useful in developing general awareness, task team leaders still felt the need for support from staff with gender expertise. For example, in all Regions, staff also cited issues in maintaining client dialogue on gender gaps, especially given deep-seated norms that perpetuate gender inequality. Task team leaders and investment officers expressed the need for staff with gender expertise to be part of client dialogue, not just about design, but throughout implementation.

Task team leaders, project leads, investment officers, and practice managers stressed in interviews and focus groups that developing and maintaining a focus on gender gaps across the project cycle requires a large investment of effort, which they are sometimes unable to provide. Developing and maintaining a gender gap approach was reported to require additional efforts to identify and contextualize evidence; adapt gender analysis during restructuring; and convince all staff members of the importance of gender. Since other corporate mandates (such as climate, fragility, and environmental and social compliance) compete for attention, task team leaders and investment officers reported, staff may not consider gender issues, particularly when they do not have access to gender expertise.

Many investment officers outside of FIG also reported that they lacked the knowledge to engage clients and develop demand, relying instead on focal points and gender leads. As noted above, only 66 IS projects were flagged. Of these projects, 42 out of 66 (64 percent) were in the FIG industry group, which is focused on lending to women and women-led small and medium enterprises. For example, the Banking on Women investment portfolio exceeded $2.5 billion in commitments by February 2020. The Manufacturing, Agribusiness, and Services group flagged the second-largest number of projects (20 percent), followed by Disruptive Technologies and Funds (14 percent) and Infrastructure (3 percent). In most cases, investment officers wanted to learn more, but outside of FIG, few were sure how to proceed in their industry. Some investment officers reported that they had championed the incorporation of gender into their operations, seeing it as an important opportunity. A minority of investment officers reported gender as a burden in seeking to make deals with clients.

Interviewees suggested that undertaking repeat AS with clients could help establish IS by introducing the application of a gender lens to the business case for targeting market gaps. Examples of AS translating to IS were cited within FIG from Lebanon and West Bank and Gaza (IFC 2016b, n.d.). However, no examples were cited outside of FIG and a review of the investment project data found limited opportunities for repeat business to introduce gender issues. Interviewees reported that many IFC clients, though generally supportive, are still on a journey to understanding how to close gender gaps when working with suppliers or delivering services to customers. Many investment officers, meanwhile, reported difficulties in developing client demand. To improve the action and awareness of gender across industries, IFC has developed advisory programs and case studies to make a business case for increasing opportunities. Business cases have been implemented for Women on Boards and in Business Leadership, the Women’s Employment Program, and community stakeholder efforts in infrastructure and natural resources. Interviewees noted that these efforts were helpful, but no evidence arose during the review for how these and other services translate into new investments that would help close gender gaps or shift the way markets operate. IEG evaluations also confirm the lack of evidence in developing IS from AS (World Bank 2017d). Although corporate commitments are present within the World Bank and IFC, awareness among task team leaders, project leads, and investment officers is not yet at a level to ensure consistent implementation. Commitment is a prerequisite, but other internal actions, such as synergies in the country portfolio and the development of staff designated to support work on gender, are also needed. The next chapter describes variations in the country-driven approach to addressing gender gaps.

- Three premises are at the foundation of its framework: (i) households are heterogenous entities composed of individuals with varying preferences and needs; (ii) markets and institutions influence the relationship between economic development and gender equality on a direct and indirect basis; and (iii) markets and institutions are dynamic, and their attributes can change and evolve in response to society and to external stimuli, such as policy interventions. The domains of gender equality are human endowments, economic opportunity, and voice and agency.

- A Gender Entrepreneurship Markets program was launched in December 2004 to mainstream gender issues into all dimensions of International Finance Corporation work, while at the same time helping to better leverage the untapped potential of women and men in emerging markets. In 2010, the initiative was renamed Women in Business.

- In addition to the Gender-Based Violence Task Force, the World Bank Group has developed guidance documents to safeguard protection in investment project financing.

- In addition to the reports cited in this section, the International Finance Corporation developed 38 reports, over 60 case studies, and nearly 30 blogs and other documents between 2016 and 2019.

- Including the World Bank Group president; World Bank managing directors, senior vice presidents, and chief operating officer; and International Finance Corporation chief executive officer and chief operating officer.

- See, for example, IFC 2020; Malpass 2020; World Bank 2018f.

- Both the Gender Group and the Gender Business Group also track changes, such as the uptake of knowledge, training of focal points, and the treatment of gender in diagnostics and strategies. Although monitoring of internal processes can support implementation, the tag and flag provide the most direct indication of the extent to which the Bank Group intends to address gender gaps.