A Focused Assessment of the International Development Association’s Private Sector Window

Chapter 3 | Enabling Factors

International Development Association (IDA) Private Sector Window (PSW) concessionality enables PSW projects to materialize. Without it, the International Finance Corporation (IFC) and the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency could not execute high-risk transactions in PSW-eligible countries because their cost of risk would make their pricing uneconomical for local borrowers.

PSW projects meet the minimum concessionality principle, which mandates that IDA concessionality should not be greater than necessary to induce the intended investment and ensures that IFC and the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency do not distort markets.

The IDA capital allocated to the PSW is underleveraged. Currently, IDA sets aside capital for the maximum potential loss that could occur—an extremely conservative capital reserve.

Periodic reports on the profits and losses of IDA, IFC, and the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency for the PSW overall and for its facilities and instruments are currently not available.

Nearly three-quarters of PSW projects anticipate a combination of financial and nonfinancial additionalities. Financing structure, particularly long-term and local currency financing, is the most common form of anticipated financial additionality in PSW projects. Financing innovation is also high.

IFC PSW projects underuse nonfinancial additionalities, including standard setting, noncommercial risk mitigation, catalyzing policy or regulatory changes, and (to a lesser extent) knowledge and capacity building.

This chapter assesses whether concessionality has enabled PSW projects to occur and whether, along with financial and nonfinancial additionality, it has created the conditions for achieving market development and broader development outcomes. In chapter 2, we discussed that PSW projects are expected to address constraints on private sector investment and have increased the scope and scale of IFC’s and MIGA’s transactions, creating the conditions for market development. We also discussed that their objectives align with the IDA special themes and the SDGs. This chapter looks at the enabling factors of PSW projects: concessionality and financial and nonfinancial additionality. It explores whether concessionality has enabled PSW transactions to materialize and to what extent the PSW subsidies have followed the minimum concessionality principle (that is, the concessionality level should not be greater than necessary to induce the intended investment so as not to distort markets and crowd out the private sector). It then assesses whether the IDA PSW is adequately leveraged and whether decision-making by management and the Board on the IDA PSW is adequately supported by current financial reporting. Finally, it examines the types of financial and nonfinancial additionality features PSW projects include and whether these features may enable PSW transactions to have potential market development effects. We look at concessionality for both IFC and MIGA. We examine only financial and nonfinancial additionality for IFC because MIGA’s tracking of these features at the project level (in MIGA’s role and contribution) does not offer sufficient granularity to carry out this analysis.

Concessionality

Why Is Concessionality Needed?

IFC and MIGA could not execute high-risk transactions in PSW-eligible countries without IDA PSW because their cost of risk would make their pricing uneconomical for local borrowers. The level of concessionality provided by IDA PSW is estimated based on the difference between (i) a “reference price” (either a market price, if available, or the price calculated using IFC’s pricing model) and (ii) the “concessional price” being charged by the blended concessional finance co-investment (IFC 2021). Concessionality is estimated at a specific point in time—the time of project approval. IFC’s pricing is determined by its cost of funds, operations, risk, and capital. Similarly, MIGA’s pricing is determined by its cost of claims, operations, risk, and capital. For both IFC and MIGA, the cost of risk and capital allocations are dramatically higher in IDA countries because of their high risk ratings. Our estimates indicate that the pricing of IFC and MIGA transactions without IDA PSW would be 5–30 percentage points higher (depending on the client and the country) than with IDA PSW. Although risk mitigation instruments, such as collateral, guarantees, or credit insurance, could contribute to reducing IFC’s and MIGA’s pricing, these mitigation instruments are rarely available in PSW-eligible countries. Moreover, they are too expensive to enable IFC or MIGA to meet market rates for the transactions they aim to support (for example, banks targeting SMEs or companies entering new sectors). (See appendix D for more details on concessionality.)

Interviews with clients and with IFC, MIGA, and IDA staff confirm that, without the IDA PSW concessionality, IFC and MIGA could not execute most transactions they currently pursue through PSW projects. Evidence from case studies reveals that, in 15 out of 17 PSW projects examined across Burkina Faso, Cambodia, Nigeria, and Tanzania, IFC would not have been able to price the transactions at a level affordable for clients or for the projects to be viable without PSW support, given the prevailing risks in these countries. For the other two projects (both under the Working Capital Solutions Facility as part of IFC’s COVID-19 emergency response), the interviewees indicated that the transactions might have gone ahead without the PSW but would have been structured differently (for example, shorter terms, higher collateral, or guarantees required to proceed). One interview in Nigeria reported that IFC had identified a project in FY19, but the project was put on hold after the credit rating went down two notches because of political instability in the country. The deal was eventually committed, with PSW support, in FY21, after Nigeria became PSW eligible. An interview in Tanzania reported that the client rejected a deal that did not secure PSW funding. Clients mentioned that—even when IFC and MIGA provide PSW (concessional) transactions—their prices are often above those of local competitors. Interviews with clients, staff, and experts also indicated that operating without concessionality may still allow IFC and MIGA to provide financing to the higher-rated enterprises in PSW-eligible countries. Operating without concessionality would, however, allow them to work only with a limited number of the target groups they need to reach, such as microfinance companies and banks that serve SMEs and women, high-risk manufacturing firms, and firms entering untested sectors. They also indicated that concessions are essential to enable IFC to operate in local currencies in markets where foreign exchange market risks are difficult to hedge (for example, in Nigeria and Tanzania).

How Does Concessionality Work?

IDA sets aside some of its capital to provide risk-taking capacity to IFC and MIGA projects in PSW-eligible countries. The IDA capital set-aside, which the Board approves in each IDA PSW allocation, enables IFC’s and MIGA’s investment transactions in PSW-eligible countries by partially mitigating risks and potential losses of IFC, MIGA, and third-party private sector investors in these countries. The IDA set-asides for the PSW are completely backed by IDA capital. These amounts are ring-fenced so that if IDA lost the entire set-aside, its capital would decline, but it would not affect IDA’s AAA credit rating. Partially moving risks from IFC and MIGA to IDA under these set-asides allows IFC and MIGA to lower their prices to market rates and frees up headroom for them to do more transactions in PSW-eligible countries. For IFC and MIGA to take these IDA risks on to their own balance sheets would require large capital allocations and could eventually affect their credit ratings. In effect, IDA has capital that can be productively used to support IFC and MIGA.1

The four PSW facilities use various instruments. As mentioned in chapter 1 (table 1.1), the BFF, for example, uses first-loss guarantees (FLGs) and PFLGs, among other instruments. With a 40 percent FLG, for example, the PSW would cover the first 40 percent of losses on a transaction before IFC or MIGA would face any losses. Similarly, on a PFLG, the PSW would cover a percentage of the first loss on an agreed portfolio. The LCF enables IFC to make local currency loans at market rates by transferring the foreign exchange risk to the PSW via cross-currency hedges executed between the IFC and IDA treasuries. IFC converts local currency loan repayments it receives back into US dollars at the spot rate in effect at the time, whereas IDA pays IFC the US dollar amount owed at the rate that was in effect when the loan was made. If the currency remains stable or increases in value, IDA makes money. If the currency declines in value, IDA loses money, but IFC is protected. The MIGA Guarantee Facility uses FLGs and risk participation to bring down the cost of noncommercial political risk insurance to private sector lenders and investors funding projects in IDA countries, mostly in infrastructure. FLGs and risk participation also bring down the loss potential on the overall MIGA insurance policy, allowing MIGA to buy reinsurance from major reinsurance companies, effectively crowding these companies into IDA markets (see appendix D).

IFC and MIGA pay IDA for risk mitigation at concessional rates reported to the Board. On FLGs and PFLGs, IFC and MIGA pay IDA a percentage of their spread equal to the loss coverage. For example, on the first two rounds of the BOP platform, IFC paid IDA 40 percent of its spread on the IDA PSW-supported loans in the BOP platform portfolio in exchange for a 40 percent pooled first-loss coverage offered by IDA. For the LCF, IFC generally pays IDA a below-market swap rate (which represents IFC’s funding cost), agreed on each transaction, while retaining the credit spread component (as IFC retains the credit risk on LCF transactions). The concession size varies by instrument and country, depending on the difference between the commercial price and the IDA price required to enable IFC and MIGA to price their transactions at market.

Key Findings on Concessionality

IFC and MIGA follow the minimum concessionality principle. PSW projects meet the minimum concessionality principle (that is, they are not greater than necessary to induce the intended investment and do not distort the markets). Consistent with IEG’s 2021 early-stage assessment of the PSW, we found that IFC and MIGA follow a rigorous governance process to ensure that each approved transaction meets the minimum concessionality principle requirement. We confirmed that prices do not distort markets based on our review of project and blended finance approval documents, pricing documents, and evidence from case studies. Financing terms are calculated and documented using IFC’s and MIGA’s pricing models or valuation models. The prices are disclosed in the investment review memos (with comparables), approved in the concept endorsement and investment review meetings, and reviewed by the Blended Finance Committee and an IDA representative. All of these reviews are officially documented. Interviews with investment teams, credit officers, blended finance staff, IDA staff, and IFC and MIGA clients also confirmed that IDA PSW projects do not distort markets. (As mentioned earlier, in several cases, they pointed to the fact that IFC prices are higher than those of competitors.) Our review of the investment review memos, blended finance approval documents, IDA memorandum of precedent approvals, and Board papers confirmed that these documents consistently and clearly disclosed the market prices and compared IFC and MIGA pricing to market and that IFC and MIGA pricing did not distort markets. In calculating comparable market prices, all subsidized facilities from international financial institutions, state banks, or governments are excluded from the comparables.

In the absence of political risk insurance markets in many IDA countries, MIGA’s price is the price the market will bear and the price required to get the insurance policy sold. MIGA negotiates with private sector investors and lenders to agree on a price for the agreed insurance coverage. In most cases, there is no market in PSW-eligible countries for the type of insurance offered by MIGA because no other actor is selling noncommercial political risk insurance. A feasible price in these countries is usually significantly lower than what MIGA’s risk rating and pricing models would require. MIGA uses the PSW’s first-loss and shared loss coverage to shift risks to the IDA PSW, enabling MIGA to price its coverage to sell. The IDA PSW first-loss level is set in a way that meets investors’ insurance rate requirements within MIGA’s risk models. In this way, the PSW concession aims to unlock private sector participation—both reinsurance companies and commercial financiers—at premiums commercial financiers can afford and risks reinsurance companies can reinsure.

Key Findings on Leveraging IDA’s Capital to Increase Use of the PSW

IDA capital is underleveraged. Currently, IDA sets aside capital for the maximum potential loss that could occur—$1.2 billion notional outstanding amount for 2023 and $638 million notional outstanding amount for 2022 (World Bank 2022a, 2023). This means that all exposures are 100 percent covered by IDA capital, or in other words, that management expects that the whole IDA allocation to the IDA PSW could be lost and that none would be recovered through collateral or insolvency procedures. This highly conservative treatment might have been justified at the time when the IDA PSW was set up (as a pilot), given the lack of historical data on PSW transactions. However, after six years of operations, total payouts under guarantees have been only $1 million, or less than 1 percent of the total exposure. This lack of payouts indicates the potential to leverage PSW funds more, allowing IDA, IFC, and MIGA to extend more support to PSW-eligible countries.

Neither IDA nor IFC nor MIGA are modeling the risks of the PSW facilities based on historical data. Different facilities have very different risk and return profiles. For example, the LCF is exposed to high risks of local currency devaluations that can quickly and significantly affect the PSW loss rates when devaluations occur. These devaluation events are largely outside of IFC’s and IDA’s control. FLGs, conversely, take credit risk that is much less volatile and that can be effectively managed by working with clients—for example, IFC can use loan covenants to reduce exposure or restructure facilities in times of stress, reducing the amount of potential first loss through good portfolio management. For these reasons, the mix of IDA PSW products and the diversification (or concentration) of foreign exchange risks and credit risks can have a large impact on the financial performance of the PSW. This risk suggests that there may be better ways to manage the overall PSW facility allocations and distribution. Modeling the probability of default and the loss given default of the PSW portfolio, the effects of foreign exchange rate movements, and the results of PSW operations is necessary to understand the best way to manage IDA’s capital allocations and facility mix and to assess whether and how the PSW could be further leveraged. Since IFC and MIGA routinely conduct modeling on their overall portfolios, they could conduct it to get a PSW view. Modeling of the PSW portfolio could be based on the track record default data of the past six years and other proxy sources of data for similar risk profile portfolios under different stress scenarios.

Modeling the PSW portfolio and effectively managing PSW capital require analyzing the unexpected loss potential of each PSW facility and the instruments used under each facility. Unexpected loss is a risk calculation that is used to determine how much capital a financial institution needs to reserve to cover potential unexpected losses and still maintain its rating. As mentioned above, the PSW currently maintains $1 of capital for every $1 of exposure, which means that the PSW carries no leverage. Data available on different facilities show very different levels of unexpected losses associated with each of them. These unexpected losses should be estimated and reflected in the models to assess how much the PSW could increase the leverage of some facilities with no impact on IDA’s rating.

Key Findings on Management Financial Reporting on the PSW

Bank Group management and the Board have limited financial information on the PSW. Reporting on the PSW is fragmented and siloed across IFC investment units, the blended finance unit, IFC Treasury, MIGA, and IDA, with no single unit having a full view of the financial costs and benefits of the PSW for each of the three agencies and for the PSW overall. There is no picture of how risks and returns are moving from IFC and MIGA to the IDA PSW at the instrument level, at the facility (with the exception of the LCF) or agency level (that is, for IDA, IFC, and MIGA), or of what the overall financial impact of the PSW is on the Bank Group. It is difficult to know how to best use IDA PSW capital without understanding what the deployment of that capital is producing.2 Board members currently receive limited financial information on the PSW. They see the concessionality cost estimates at the time of Board approval and highly aggregated financial statement for the PSW that are included in the IDA annual financial statements. Producing financial management reports on profits and losses for IFC, MIGA, and IDA is important for management and the Board members to understand how risks move from IFC and MIGA to IDA, to make decisions on reallocating capital from one facility (or instrument) to another, and as an input for risk modeling.

Financial and Nonfinancial Additionality of the PSW Portfolio

In this section, we analyze which types of financial and nonfinancial additionality are included in PSW projects and whether these features enable projects to create the conditions to develop markets. We define financial and nonfinancial additionality, derive evidence from prior IEG work on the impact of financial and nonfinancial additionality on development outcomes, and then discuss the specific types of financial and nonfinancial additionality of PSW projects, comparing them with similar non-PSW projects in IDA countries and with (non-PSW) projects in MICs. The analysis relies on IFC additionality claims (anticipated or ex ante additionality) in PSW projects’ approval documents.

IFC defines additionality as the unique contribution that it brings to a private investment project that is typically not offered by commercial sources of finance (IFC 2018). Additionality is a threshold condition for a project’s approval and, as such, is assessed at the project level. Financial additionality is the unique support that IFC brings to a client based on the features of the financial package offered, including the financing structure (such as longer tenors and provision of local currency financing), resource mobilization (from the private sector or other DFIs), or innovative financing (such as derivatives and green bonds). Nonfinancial additionality relates to the deployment of knowledge and standards—for example, capacity building to help financial institutions assess the credit risks of MSMEs or to help IFC clients improve their environmental and social or industrial standards. Table 3.1 defines the various types of financial and nonfinancial additionality. A single project can anticipate more than one form of additionality—for example, by IFC offering both long tenor and resource mobilization or capacity building together with local currency financing to financial institutions (World Bank 2022b).

Table 3.1. Types of Additionality

|

Type and Subtype |

Description |

|

Financial additionality |

|

|

1. Financing structure |

Amount of financing provided, tenors and grace periods, and provision of local currency financing. |

|

2. Innovative financing structure and instruments |

Includes financing structures unavailable in the market that add value by lowering the cost of capital or better addressing risks (such as trade finance, derivative products, green bonds, or securitizations). |

|

3. Resource mobilization |

IFC’s verifiable role in mobilizing commercial financing from an institutional or private financier that would be delayed, reduced, or unlikely in the absence of IFC involvement. |

|

4. IFC’s own-account equity |

IFC provides equity unavailable in the market in a way that strengthens the financial soundness, creditworthiness, and governance of the client. |

|

Nonfinancial additionality |

|

|

1. Noncommercial risk mitigation, including trusted partnerships |

IFC provides comfort to clients and investors by mitigating noncommercial, nonenvironmental, and social risks, such as country, regulatory, project, or political risks, while adhering to IFC’s principle of political neutrality. |

|

2. Frameworks: catalyzing policy or regulatory change |

IFC’s involvement in a project catalyzes the investment response to changes in the policy or regulatory framework. The project is the first to test a new or untested policy, regulatory regime, or legal framework and public-private partnership model. IFC’s involvement is also likely to mitigate further regulatory changes or other risks to the project. |

|

3. Knowledge, innovation, and capacity building |

IFC plays a verifiable, active, and direct role in providing expertise, innovation, knowledge, and capabilities that are material to the project’s development impact because of the perceived weak institutional capacity of the borrower or investee. |

|

4. Standard setting |

IFC is a provider of expertise in environmental and social standards, corporate governance, insurance, and gender and is additional where the laws and market practice do not reinforce this behavior. Changes in practices have to be significant enough to matter from a development impact angle—they have to pass the “so what” test. |

Source: International Finance Corporation 2019.

Note: IFC = International Finance Corporation.

Nearly three-quarters of the PSW portfolio reviewed for this evaluation have a combination of anticipated financial and nonfinancial additionality in their approval documents. This percentage is similar to that of the non-PSW portfolio in eligible countries (69 percent) but below that of the IFC portfolio in MICs, which anticipated both financial and nonfinancial additionality for 82 percent of investment projects evaluated in 2011–21 (table 3.2).

Table 3.2. Anticipated Financial and Nonfinancial Additionality in PSW, Non-PSW Projects in IDA Countries, and Middle-Income Country Projects

|

Project Type |

Projects (no.) |

Share of Projects (%) |

||

|

Only financial |

Only nonfinancial |

Both |

||

|

PSW |

162 |

26 |

1 |

73 |

|

Non-PSW IDA |

73 |

21 |

11 |

69 |

|

MICs |

579 |

5 |

13 |

82 |

Sources: Independent Evaluation Group; World Bank 2022b.

Note: IDA = International Development Association; MIC = middle-income country; PSW = Private Sector Window.

Anticipated Financial Additionalities

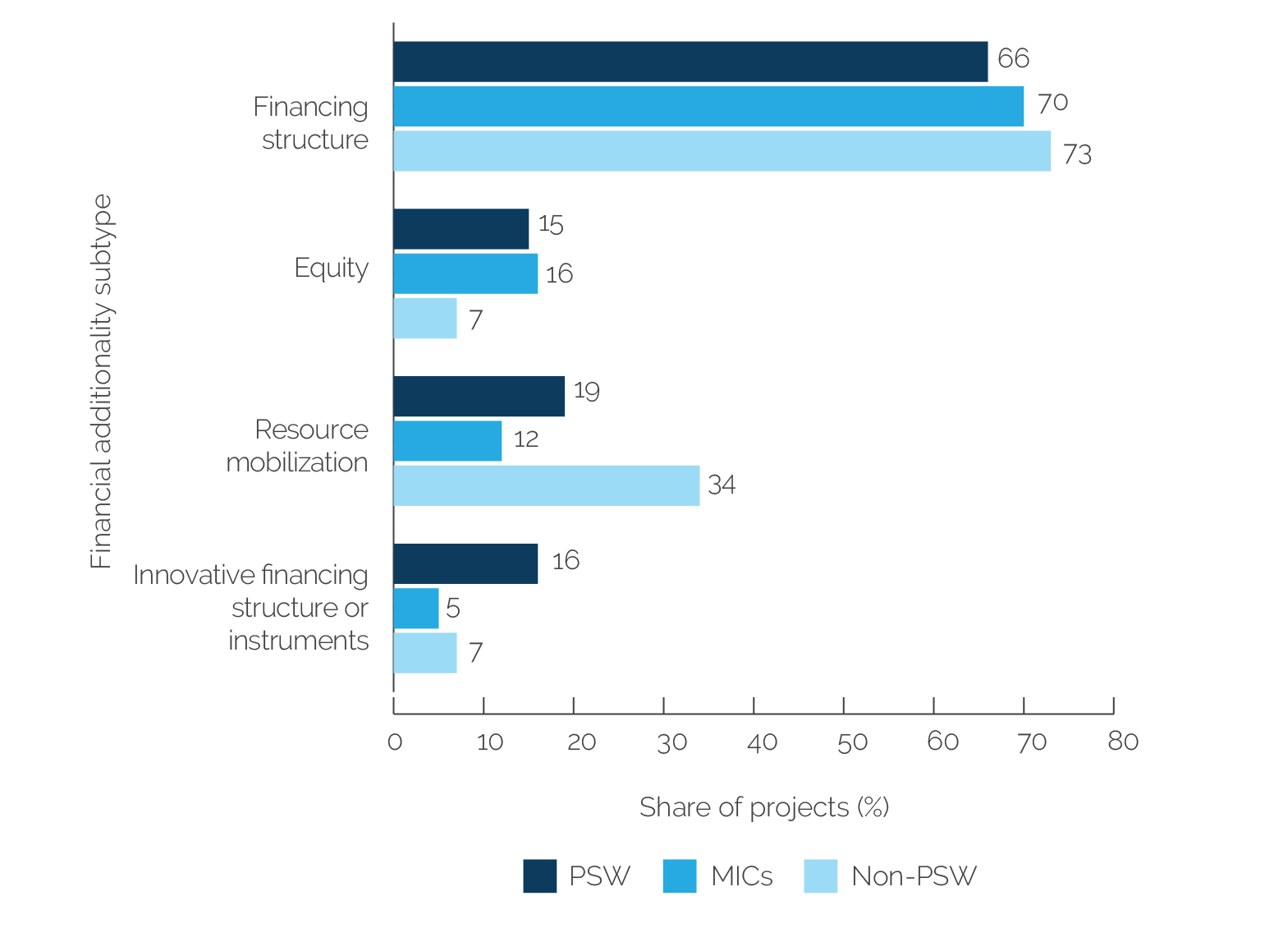

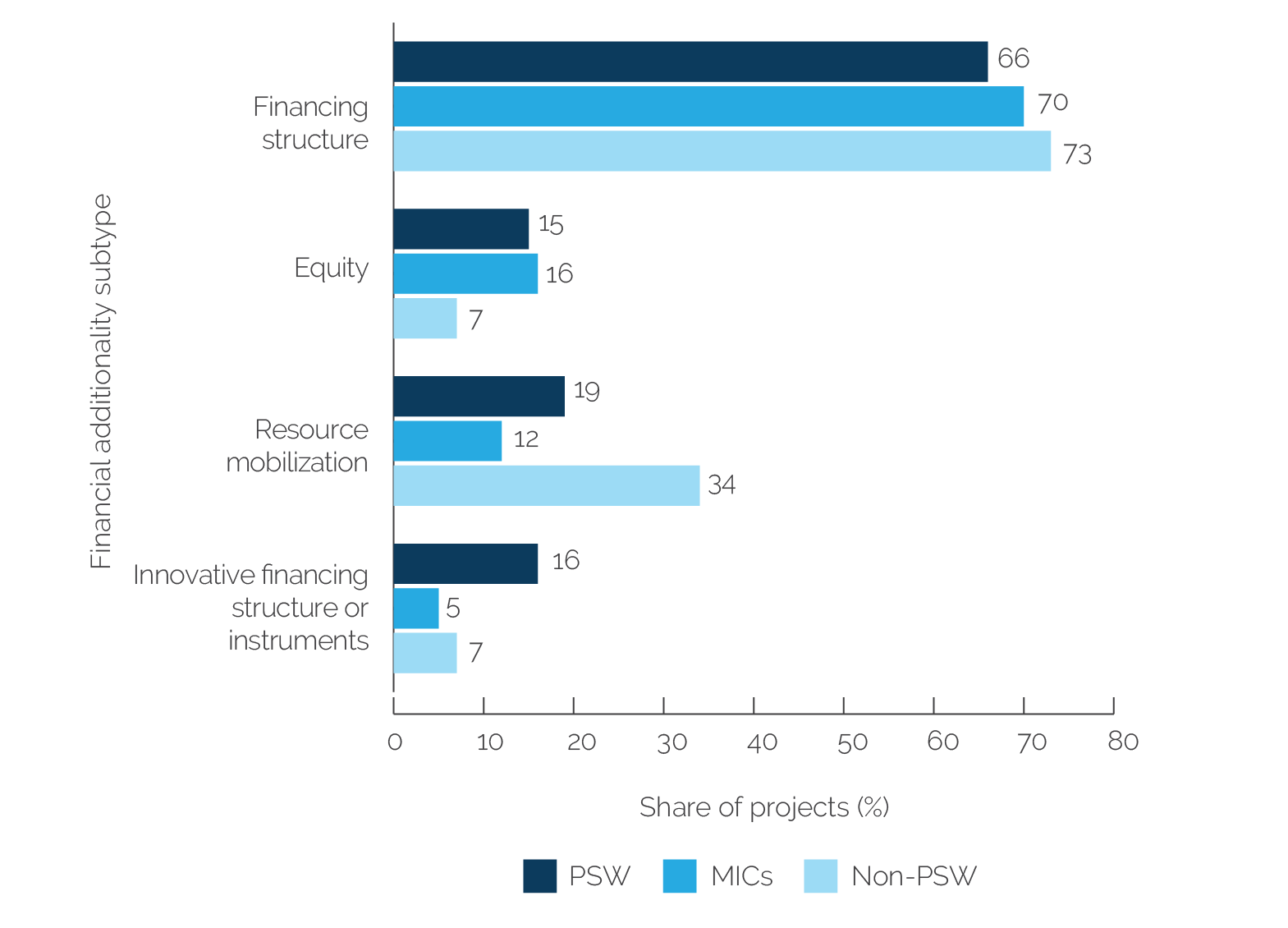

Financing structure is the most common anticipated additionality of IFC projects in the PSW, non-PSW, and MIC portfolios. Sixty-six percent of PSW projects anticipated financing structure additionality compared with 70 percent of the MIC portfolio and 73 percent of non-PSW projects in PSW-eligible countries (figure 3.1). The types of financing structure additionality described in the approval documents of PSW projects align with the challenges to private sector investment that PSW funding intends to tackle (namely, lack of long-term funding and lack of local currency financing). Provision of long-term funding and local currency financing, driven by the use of the PSW LCF, is predominant.

Figure 3.1. Anticipated Financial Additionality Subtypes by Country Types

Sources: Independent Evaluation Group portfolio review; World Bank 2022b.

Note: Number of projects: MICs = 570, PSW = 168, and non-PSW in IDA = 71. IDA = International Development Association; MIC = middle-income country; PSW = Private Sector Window.

The PSW portfolio has a higher incidence of anticipated innovative financing structure additionality compared with the non-PSW and MIC portfolios. Innovative financing structure additionality is more common in the PSW portfolio (16 percent) than in the non-PSW portfolio in IDA countries (7 percent) and in MICs (5 percent). The difference is significant at the 95 percent confidence level. Innovative financing structure additionality refers to IFC using financing structures that it has not offered before in the country and that other financiers also do not offer. The “innovative financing” claim in the PSW portfolio is mostly based on the use of PSW PFLGs in IFC’s projects of the Small Loan Guarantee Program. The presence of other innovative financial products under this type of additionality (for example, green bonds, gender bonds, and derivatives) is limited. A PSW project in Nigeria (ID 44985) with a local bank provides a good example of a typical innovative financing structure in PSW projects. The investment aimed to increase the local bank’s lending to SMEs, particularly women-owned and climate-smart SMEs. The project was processed under the Small Loan Guarantee Program, which uses a pooled first-loss structure provided by the IDA PSW BFF. The project consists of an unfunded risk-sharing facility of up to $10 million equivalent in local currency, which guarantees 50 percent of an up to $20 million equivalent portfolio of eligible SME and women-owned SME facilities extended by the local bank. IFC considered this structure innovative in Nigeria because IFC’s risk-sharing facility is flexible regarding the types of loans and facilities that can be included in the portfolio (such as working capital loans and longer-tenured loans). Hence, it can help meet the wide range of SME financing needs more effectively than other financing available in the local market.

Mobilization expectations in the PSW portfolios are lower than in non-PSW IDA projects but higher than in MICs. IFC claims resource mobilization additionality when IFC plays a direct and verifiable role in mobilizing financing from other public or private investors. Consistent with the (ex post) findings of chapter 2 and the risk profile of PSW transactions, anticipated resource mobilization additionality claims are less common in PSW than in non-PSW portfolios in IDA countries (19 percent compared with 34 percent, respectively). They are, however, still above those in MICs (12 percent).

Anticipated Nonfinancial Additionalities

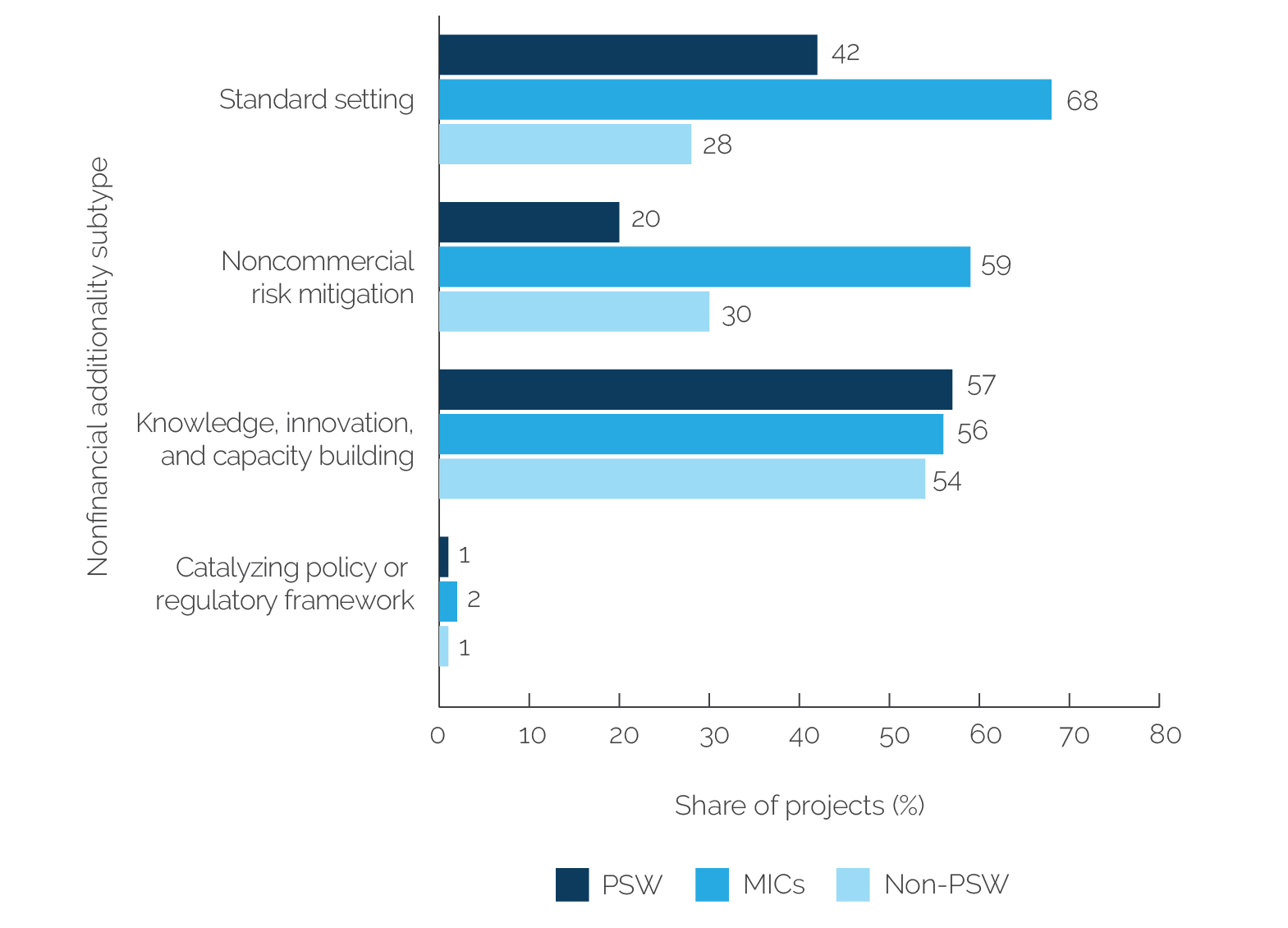

When comparing the different types of anticipated nonfinancial additionalities across PSW, non-PSW, and MIC portfolios, some particularities stand out. The first is that there is almost no difference in knowledge and capacity building across the three portfolios (figure 3.2). The second is that there are low levels of standard-setting additionality in the (PSW and non-PSW) portfolios of PSW-eligible countries. The third is that the PSW portfolio has the lowest incidence of noncommercial risk mitigation among the three. Finally, there is a very low incidence of catalyzing regulatory reforms (which is in line with the rest of the IFC portfolio).

Figure 3.2. Anticipated Nonfinancial Additionality Subtypes by Country Types

Sources: Independent Evaluation Group portfolio review; World Bank 2022b.

Note: Number of projects: MICs = 570, PSW = 168, and non-PSW in IDA = 71. IDA = International Development Association; MIC = middle-income country; PSW = Private Sector Window.

The incidence of knowledge and capacity building is similar across the IFC portfolio, but the incidence of standard-setting features in PSW-eligible countries is low for both PSW and non-PSW projects. The incidence of knowledge, innovation, and capacity-building additionality in the PSW portfolio is 57 percent, which is in line with that in the non-PSW portfolio in eligible countries (54 percent) and with that of the MIC portfolio (56 percent). Standard-setting additionality is significantly lower in PSW-eligible countries (42 percent for the PSW portfolio and 28 percent for the non-PSW portfolio) than in MICs. Improving knowledge and capacity building and improving clients’ capacity to adopt and implement environmental and social standards is particularly important in PSW-eligible countries to address the high risks they face.

Low claims of IFC playing a “comforting” role in PSW projects are at odds with the PSW’s objective of pursuing market development. Noncommercial risk mitigation additionality is significantly lower in PSW projects than in projects in MICs (20 percent compared with 59 percent, respectively). It is also lower than in non-PSW projects in eligible countries (30 percent). This additionality signals IFC’s expectations that its presence in the project will comfort clients and other investors to mitigate noncommercial risks, such as country, regulatory, or political risks, because of IFC’s and the Bank Group’s reputation in the market. The ultimate expected outcome of noncommercial risk mitigation is that IFC’s presence would crowd in other investors who will contribute to or replicate the project on their own (or with other partners). The reasons for this low additionality are unclear and should be further investigated. They could range from IFC not expecting other investors to follow, given the high-risk profile of the markets and projects, to IFC underreporting this additionality in approval documents.

The IFC PSW portfolio also underuses catalyzing policy or regulatory change additionality. This additionality signals that IFC is the first investor to test a new or “untested” policy, regulatory, or legal framework, opening the door for others to follow. Yet, the presence of this additionality in PSW projects is negligible, as it is in the rest of the portfolio. This low incidence of catalyzing policy or regulatory change additionality could be either because the enabling environment is not ready for private sector investment, because IFC is not proactively monitoring relevant regulatory changes that open the door for investment, or because it is not seeking these types of interventions because it perceives them as too risky.