A Focused Assessment of the International Development Association’s Private Sector Window

Chapter 2 | Private Sector Window Usage and Market Development Potential

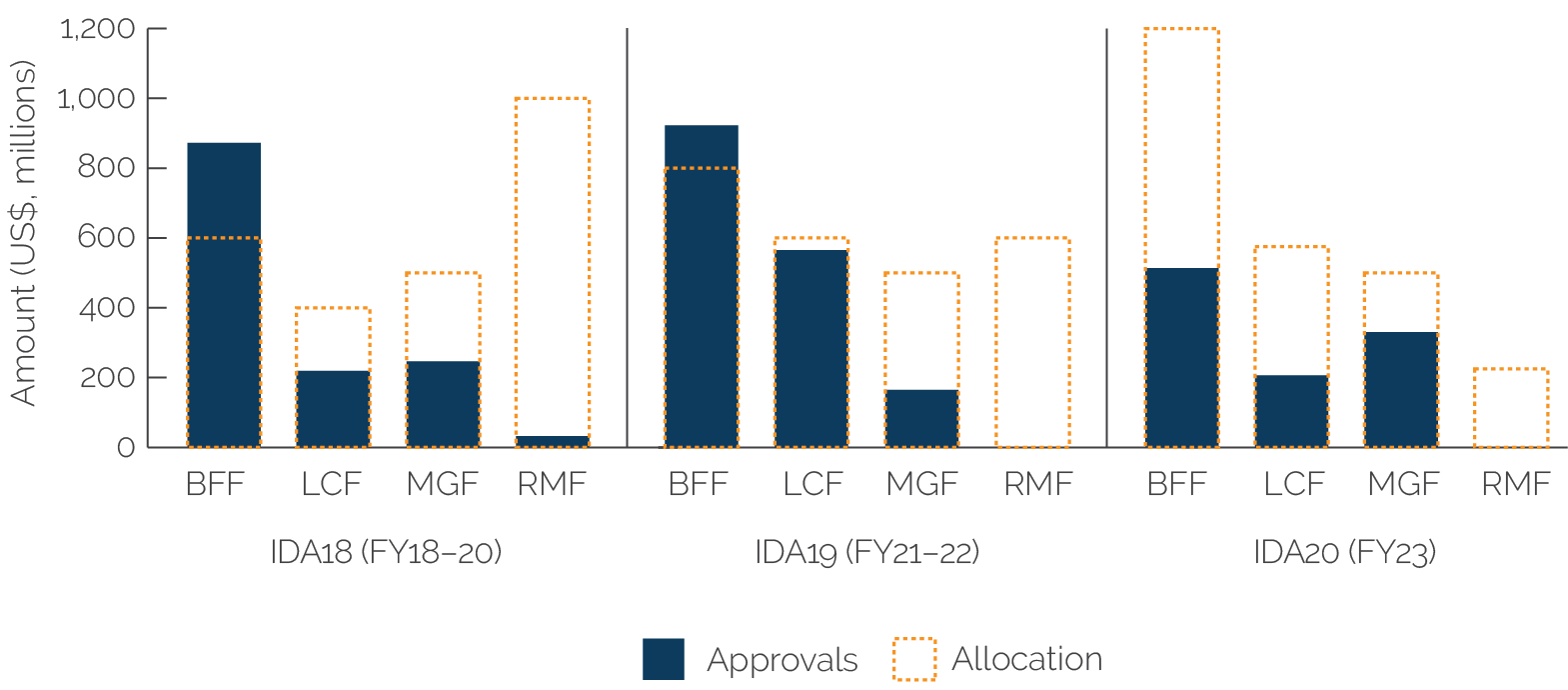

Private Sector Window (PSW) funds were underused in the 18th Replenishment of the International Development Association (IDA18) but almost entirely used in IDA19 and are on course for full use in IDA20. Uptake of IDA funds has accelerated in IDA19 and IDA20, from 6 percent approved funds in the first year of IDA18 to more than 30 percent in the other two cycles. Usage has been strongest for the Blended Finance Facility and weakest for the Risk Mitigation Facility. Usage of the Local Currency Facility is growing, and usage of the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency Guarantee Facility is stable.

Although non-PSW projects in eligible countries aim to address mostly one constraint on private sector investment in IDA countries and fragile and conflict-affected situations—lack of long-term finance—PSW projects aim to address a variety of constraints by providing (i) local currency financing in the absence of a local currency to US dollar swap market; (ii) long-term finance in countries where it is not available; (iii) emergency funding that local financial institutions would not be able to provide to address disruptions as a result of exogenous factors (such as the trade collapse and increases in input prices during the COVID-19 pandemic and the energy crisis); and (iv) guarantees to operate in an unfavorable business environment (for example, insurance against political risks).

The PSW has enabled the International Finance Corporation to commit a higher investment volume in PSW-eligible countries than it would have without PSW support. The PSW has also enabled the International Finance Corporation and the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency to enter new countries and invest in new sectors (for example, mobile money and equity funding for small and medium enterprises) in PSW-eligible countries.

PSW projects mobilized third-party private and public capital, although, as expected, to a lesser extent than non-PSW projects in IDA countries and projects in middle-income countries, given their higher risks. Mobilization of private capital in IDA countries and fragile and conflict-affected situations is important to help the market generate information about the viability of transactions.

PSW projects are ex ante broadly aligned with the IDA special themes. However, not all of them have objectives related to jobs and economic transformation, as envisioned at the time the PSW was created, and climate and gender objectives are unevenly covered.

This chapter covers several interrelated aspects of the PSW: (i) its usage, (ii) its ability to address constraints on private investment, and (iii) its potential to create the conditions for market development and to achieve broader development outcomes. First, we measure the PSW usage against the initial PSW allocations for the three IDA replenishment cycles (IDA18, IDA19, and IDA20) since the PSW’s inception in FY17. Usage is a necessary but not sufficient condition for the PSW to achieve its ultimate goals of developing markets, helping eligible countries address the IDA special themes, and making progress toward the SDGs. Thus, the second part of the chapter looks at whether the PSW aims to address key constraints on private investment and whether PSW projects have enabled IFC and MIGA to create the conditions to develop markets in PSW-eligible countries. We do so by examining whether IFC and MIGA have improved the scope (creating, developing, or sustaining new markets and sectors) and scale (increasing business in countries and sectors) of their investments and by looking at whether the PSW has mobilized third-party private capital in risky transactions. The chapter closes with a brief assessment of whether PSW transactions are aligned with the IDA special themes and the SDGs.

The analysis of PSW usage and market development potential is based on both ex ante and ex post data. Although, as mentioned in chapter 1, we do not have sufficient numbers of closed PSW projects and PSW projects that IEG evaluated to conduct a full result assessment, our findings are based on analysis of both ex ante and ex post data. We extract ex ante data from project approval documents. Ex ante analysis excludes information on the execution or achievement of results (for example, no indication of whether a transaction has materialized or on the realization of expected development outcomes). We extract ex post data from project supervision documents or case studies. This captures data on PSW transactions that have taken place and achieved intermediate development outcomes—for example, PSW transactions that have allowed IFC and MIGA to invest in new countries and sectors. The usage and the scope and scale analysis are based, by and large, on ex post portfolio data, as 86 percent of the PSW projects have been committed (190 of 220), 92 percent of which (175 of the 190 committed projects) have either disbursed (101 investments) or have provided guarantees that have been issued (45 guarantees for IFC and 29 guarantees for MIGA). The analysis of whether PSW transactions address market constraints is based on a mix of ex ante and ex post data, with the latter being based partially on the portfolio analysis and mostly on evidence gathered from country case studies. The analysis of the market potential of PSW projects, which complements the scope and scale analysis, is based on a summary assessment from ex ante portfolio information (PSW projects’ Anticipated Impact Measurement and Monitoring rates).

Usage

After a slow start in IDA18 (FY18–20), usage of PSW funds increased and accelerated in IDA19 (FY21–22) and IDA20 (FY23–25). Initial allocations for all three IDA cycles were $2.5 billion for three years, but IDA shortened IDA19 to two years because of COVID-19 and revised its PSW allocation from $2.5 billion to $1.67 billion. PSW funds were underused in IDA18 (with only 53 percent of the initial allocation used) but almost entirely used in IDA19 (after factoring in the shortening of the IDA19 cycle). The PSW is on course for full use in IDA20 if the current usage level for FY23 continues in FY24–25 (figure 2.1). Uptake of IDA funds (measured as the percentage of allocation approved) has also been quicker in IDA19 and IDA20 than in IDA18. The total amount of PSW funds approved in the first FY under IDA18 was $144 million (6 percent of allocation), $548 million in IDA19 (33 percent of the allocation based on a two-year cycle), and $900.5 million in IDA20 (36 percent of the allocation). Evidence gathered for this evaluation suggests that this increased usage and quicker uptake may be linked to improvements in PSW administration and increased trust among the three agencies. Case study interviews indicated that, in the early periods after inception, PSW usage was challenging for project teams because of time-consuming “paperwork” and approval processes, knowledge gaps related to the existence and functioning of the PSW, and trust gaps among different stakeholders. They indicated that these constraints have ameliorated over time.

Figure 2.1. Cumulative PSW Approvals across IDA Cycles

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: IDA19 received an initial allocation of US$2.5 billion, meant initially for three years. However, IDA shortened the cycle to two years because of COVID-19, and we have adjusted the allocation figures accordingly. The IDA20 allocation is for FY23–25, but the figure shows IDA20 approvals for FY23 only. FY = fiscal year; IDA18 = 18th Replenishment of the International Development Association; PSW = Private Sector Window.

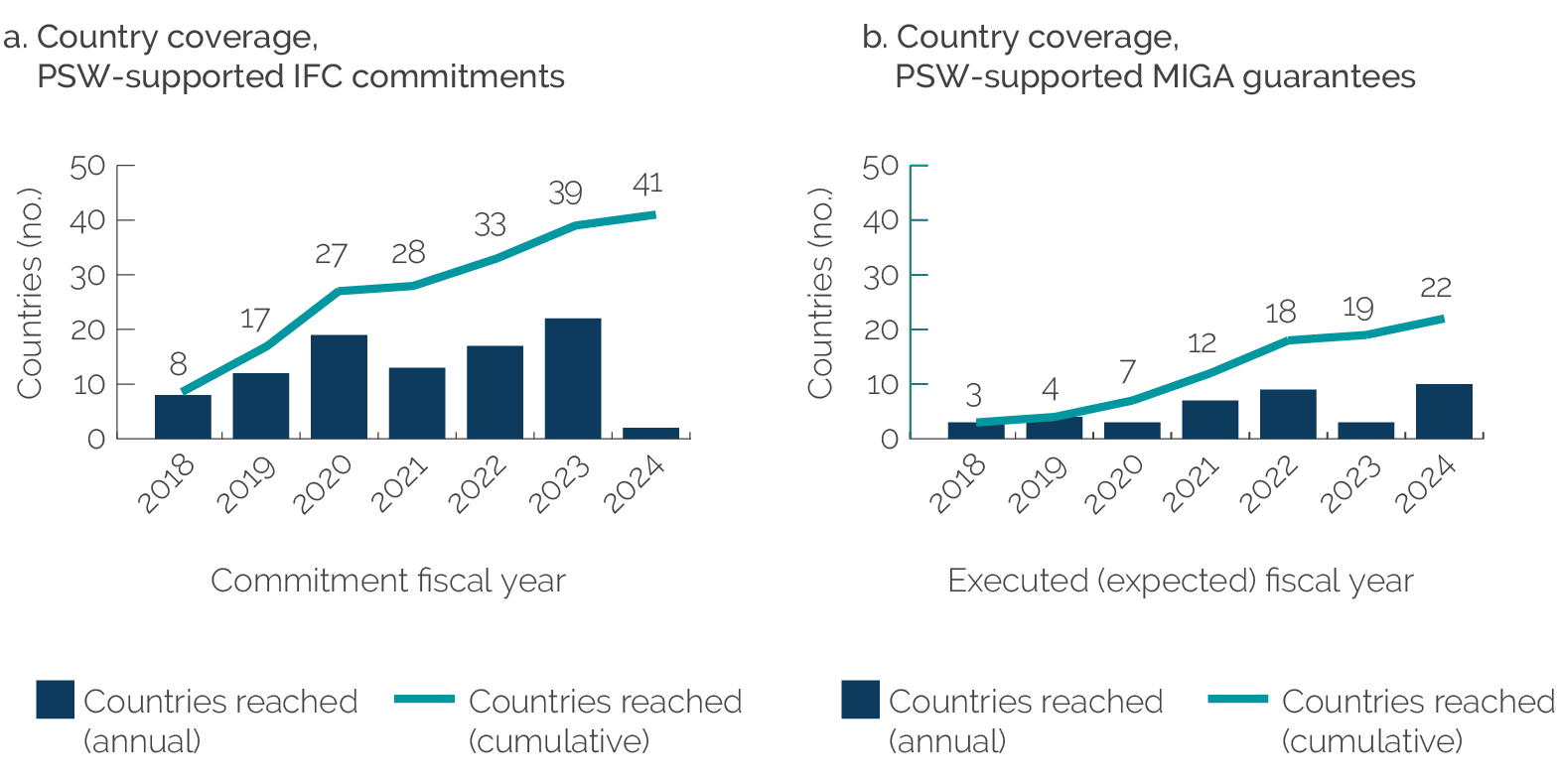

Usage varies by PSW facility, and allocations to PSW facilities have been adjusted based on use in the previous cycles. The BFF has been overused in each of the three IDA cycles, whereas RMF was used for only one project in the IDA18 cycle with no further usage in IDA19 and IDA20 (figure 2.2). As a result, the share of PSW funds allocated to the BFF has increased progressively with each cycle from $600 million per three-year cycle (or $200 million a year) in IDA18 to a range of $1.2 billion to $1.5 billion per three-year cycle (or $400 million to $500 million a year) in IDA20. In contrast, allocations for RMF have decreased substantially (from $1 billion during IDA18 to a range of $150 million to $300 million in IDA20). Utilization of the LCF was below allocation in IDA18 but increased beyond allocation in IDA19 and is headed toward overuse in IDA20. Approvals for LCF, which totaled $219 million in the three-year IDA18 cycle, jumped to $565 million in the two-year IDA19 cycle and have already reached $206 million in the first year of IDA20. Allocations for the MIGA Guarantee Facility have remained the same across all three IDA cycles ($500 million per three-year cycle or $167 million annually). Usage was below allocation and stable in IDA18 and IDA19 but increased in IDA20 (average yearly approvals stood at $82 million in each of IDA18 and IDA19 but increased to $110 million in IDA20). The increase in MIGA Guarantee Facility usage in IDA20 is because of one telecom project that accounts for two-thirds of MIGA Guarantee Facility approvals in IDA20.

Figure 2.2. Allocations and Approvals by IDA Cycle and PSW Facility

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: The figure shows the approvals and allocations for each Private Sector Window facility across IDA cycles. The numbers presented are the total for the full length of each IDA cycle as of June 2023: three years for IDA18, two years for IDA19, and one year for IDA20. IDA20 allocations are in ranges as follows: US$1.2 billion to US$1.4 billion for BFF, US$150 million to US$300 million for RMF, US$500 million to US$650 million for LCF, and US$500 million for MGF. For charting purposes, the allocation numbers shown for IDA20 in the figure are the averages adjusted so that the total adds up to the total IDA20 allocation of US$2.5 billion. BFF = Blended Finance Facility; IDA18 = 18th Replenishment of the International Development Association; LCF = Local Currency Facility; MGF = Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency Guarantee Facility; PSW = Private Sector Window; RMF = Risk Mitigation Facility.

The different usages of the facilities reflect their capacity to respond to client needs. The BFF is highly flexible (table 1.1). It has been used to support different types of operations ranging from providing short- and long-term finance to issuing guarantees to clients across multiple sectors. The increase in LCF approvals in IDA19 and IDA20 likely reflects increased demand for local currency hedging in the face of growing local currency risks in major PSW-recipient countries, such as Côte d’Ivoire, Nigeria, and Tanzania. In Nigeria, for example, a wide and growing arbitrage between the official exchange rate and the market rate posed a high currency devaluation risk for several months. Then, in June 2023, the government formally floated the local currency, causing the official exchange rate to drop by 40 percent. Meanwhile, IEG’s earlier assessment found that the severe underuse of RMF might have resulted from the similar role of existing risk-mitigating instruments across the Bank Group. The project-based guarantees for infrastructure projects offered by RMF are similar to the IDA’s partial risk guarantees (which, unlike RMF, also cover sovereign risk) and the political risk insurance offered by MIGA.

Across all three IDA cycles, PSW projects concentrate on the finance industry group for IFC and on infrastructure for MIGA. Finance industry group projects account for 70 percent of approvals (table 2.1) of the three facilities managed by IFC as of the end of FY23. This concentration reflects the high demand for short-term finance during the COVID-19 crisis and the scarcity of local currency financing throughout all three IDA cycles. Eighty percent of PSW MIGA projects are in infrastructure.

Table 2.1. Sectoral Distribution of PSW Facility Approvals, Fiscal Years 2018–23

|

IFC Industry Group and MIGA Sector |

IFC: BFF, LCF, RMF (US$, millions) |

Share of IFC (%) |

MIGA: MGF (US$, millions) |

Share of MIGA |

Overall Share, All Facilities |

|

Financial institutions |

2,329 |

70 |

47 |

6 |

58 |

|

Funds |

198 |

6 |

0 |

0 |

5 |

|

Infrastructure |

361 |

11 |

672 |

84 |

25 |

|

Manufacturing, agribusiness, and services |

434 |

13 |

77 |

10 |

12 |

|

Total |

3,322 |

100 |

796 |

100 |

100 |

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: BFF = Blended Finance Facility; IFC = International Finance Corporation; LCF = Local Currency Facility; MGF = MIGA Guarantee Facility; MIGA = Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency; PSW = Private Sector Window; RMF = Risk Mitigation Facility.

The Role of the Private Sector Window in Addressing Constraints on Private Investment

PSW-supported IFC and MIGA projects aim to address a variety of constraints that inhibit private investment in PSW-eligible countries. The constraints are created mainly by limited long-term finance, the absence of local currency financing, market disruptions as a result of exogenous factors, and unfavorable business environments in these countries. Without functional foreign currency swap markets, local currency financing is unavailable. Long-term finance (in foreign or local currency) is also often unavailable in PSW-eligible countries, particularly for micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs). Examples of market disruptions as a result of exogenous factors are the collapse of trade and the increase in input prices because of the COVID-19 and energy crises. Unfavorable business environments are characterized by high political risks and weak legal and regulatory structures for the economy and specific industries (for example, poor frameworks for public-private partnerships affecting the infrastructure sectors).

Our case study evidence indicates that PSW projects expect to address more investment constraints than non-PSW projects in eligible countries. We compared the investment constraints addressed by 30 nonconfidential PSW projects in case study countries (Burkina Faso, Cambodia, Nigeria, and Tanzania) with those addressed by non-PSW projects in the same sectors of the same countries. The (ex ante) analysis was based on project approval documents for both samples. Figure 2.3 reports the results of the analysis. We found that all PSW projects aimed to address one or more of the four aforementioned causes of constraints. In contrast, the vast majority of non-PSW projects focused on a lack of long-term finance, and a few aimed to address disruptions as a result of exogenous factors. Hardly any aimed to tackle local currency financing, and none aimed to mitigate risks arising from an unfavorable business environment. Although these results are not representative of the whole PSW portfolio, they provide a sense of the breadth of constraints limiting private investment that PSW projects aim to address. The following sections—based on the findings of the case studies and, when possible, portfolio analysis—detail how PSW projects addressed these constraints.

Figure 2.3. Constraints on Private Investment that PSW and Non-PSW Projects in Case Study Countries Aim to Address

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: The results are based on 30 nonconfidential PSW projects and 19 non-PSW projects in case study countries (Burkina Faso, Cambodia, Nigeria, and Tanzania). The bars denote the share of reviewed projects addressing each constraint. PSW = Private Sector Window.

How the PSW Addresses Absent Local Currency and Long-Term Finance

There is no local currency to US dollar swap market in many PSW-eligible countries because of high country risk, including macroeconomic or political uncertainty. The absence of a local currency swap market stalls or disrupts the forward foreign exchange hedging markets, making hedging expensive or impossible. This absence has made it difficult for financial institutions to raise funds in local currency, leading them to opt for foreign currency loans, which expose them—and their clients—to foreign exchange risks and increase borrowing costs. The nascent development of many PSW-eligible countries also means there is often a lack of local market liquidity for lending, particularly (but not only) at longer tenors. As a result, the private financial sector in these countries cannot provide sufficient credit denominated in local currency.

In PSW-eligible countries, long-term financing (in foreign or local currency) is also very limited or absent, especially for MSMEs. Long-term financing is essential for infrastructure investment, for housing finance, and for companies to acquire the equipment and premises needed to produce, store, and sell their goods. Developing long-term financing requires institutional reforms, such as promoting macroeconomic stability, establishing a regulated and legally enforceable banking and investment system that protects creditors and borrowers, and setting a framework for capital markets and institutional investors (World Bank 2016). Without these reforms and financial institutions with the capacity to assess the creditworthiness of their borrowers, private firms and households do not have access to long-term finance and, therefore, have to use their own resources or short-term loans to fund their investment needs.

Through PSW projects, IFC has provided local currency and long-term funding to several PSW-eligible countries, sometimes complementing financing with advisory services. Of 161 PSW-financed IFC projects committed to date, 43 (27 percent of the total) provided local currency financing, and 91 (57 percent of the total) reported in their approval documents providing financing with tenors longer than usually available. Projects that provided local currency or long-term financing have taken place in all four case study countries (Burkina Faso, Cambodia, Nigeria, and Tanzania). In Cambodia, for example, IFC subscribed to a three-year Cambodian riel-denominated bond supported by the PSW LCF. This was the country’s first local currency bond issuance. Cambodian corporates had issued no bonds in the past in any currency, and 79 percent of loans issued 12 months prior had a maturity of five years or less. The riel-denominated bond supported by the PSW LCF gave rural clients access to local currency financing for the first time. The bond issuance also set a benchmark for future riel bond issuances. Through a successful issuance and listing, IFC helped establish a benchmark for pricing, structure, and public disclosure for future transactions. In Tanzania, IFC subscribed to a three-year senior gender bond supported by the PSW LCF. As one interviewee put it, the project allowed IFC to “lengthen the maturity of the bonds in the market and even build the yield curve for corporate bonds in the market.”

How the PSW Addresses Market Disruptions because of Exogenous Factors

PSW-eligible countries can be strongly affected by market disruptions because of exogenous factors. Exogenous factors include, for example, the recent global COVID-19 pandemic, food, and energy crises. These disruptions can cause a mismatch between the supply and demand for financing, potentially disrupting or destroying existing markets. Global crises and their consequences are likely to affect PSW-eligible countries more than middle-income countries (MICs) because governments and private firms in PSW-eligible countries do not have sufficient resources to cope during these times.

To address these challenges, PSW projects have provided short-term financing to help private companies circumvent the liquidity crunch. Examples include the Working Capital Solutions Crisis Response Facility in countries such as Cambodia, Nigeria, and Tanzania, which benefited from the pooled first-loss guarantee (PFLG) product offering provided by the IDA PSW BFF. The Base of the Pyramid (BOP) platform is another example of a crisis instrument that used the PSW facilities to provide finance to private companies, including MSMEs, in PSW-eligible countries. This platform was set up under the IFC COVID-19 Facility to reach MSMEs in more fragile markets, with three-year liquidity support delivered through IFC client banks and microfinance institutions. It aimed to “keep the private sector going” while the COVID-19 crisis severely disrupted markets. The platform has been extended twice, with the latest extension allowing up to five-year tenors and reducing the first-loss level from 40 percent to 30 percent. A snapshot of projects in the BOP platform’s portfolio (as of June 2023) shows that the platform has been successful in helping IFC reach firms in PSW-eligible countries by deploying both the PSW BFF through PFLG (27 projects) and the PSW LCF (19 projects).

How the PSW Addresses Unfavorable Business Environments

An unfavorable business environment is characterized by poor macroeconomic policies and a lack of—or inappropriate—legal and regulatory frameworks for the economy or specific industries. Examples of constraining factors in the business environment include macroeconomic instability, nationalization, expropriations, and weak regulatory frameworks for private investment, capital market development, and access to finance. These constraints affect all economic sectors and are widespread in IDA countries and FCS. Weak legal and regulatory frameworks that affect specific industries—such as market entry barriers in network or contestable sectors (for example, energy, telecom, and agriculture)—often compound their disruptive effects.

MIGA’s PSW-supported guarantees aim to create enabling environments for private investment in poor and fragile countries by insuring private investors’ investments against risks. Infrastructure sectors in PSW-eligible countries struggle to attract private investments because of political risks, such as nationalization, expropriation, and social unrest, resulting in a funding gap for critical services. All of MIGA’s PSW projects—29 guarantees—aim to insure private investors against political risks. One example is MIGA’s PSW-supported guarantee to the energy sector in Burkina Faso, where only 20 percent of the population has access to electricity (compared with the already low 48 percent for Sub-Saharan Africa). Burkina Faso also has a high end user electricity cost ($0.24 per kilowatt-hour in Burkina Faso compared with $0.11 per kilowatt-hour in Senegal, $0.12 per kilowatt-hour in Côte d’Ivoire, and an average of $0.14 per kilowatt-hour in Sub-Saharan Africa).<1 In addition, political unrest, including repeated coups, has deterred private investment in energy and other sectors. Amid these challenges, MIGA’s guarantees support private investments in three solar power projects, enabling the country’s first round of independent solar power producers. With PSW support, MIGA is insuring private investments in these projects against the risks of transfer restriction and inconvertibility, breach of contract, expropriation, and war and civil disturbance for a tenor of up to 20 years. Two of these projects have been under implementation for two years, aiming to bring clean and affordable power to the country. (The third project has been delayed because of construction cost overruns.) The solar power projects are expected to supply energy at a lower tariff than the current electricity production cost from thermal power plants. This expected cost reduction could make Burkina Faso’s electricity sector more competitive by forcing producers of energy from other sources to either become more cost-efficient or exit the market. It is also expected to deliver important demonstration effects for the country and future prospective investors by exhibiting the viability of the independent power producer approach in the solar energy sector.

Scaling Up Engagement for Market Development in PSW-Eligible Markets

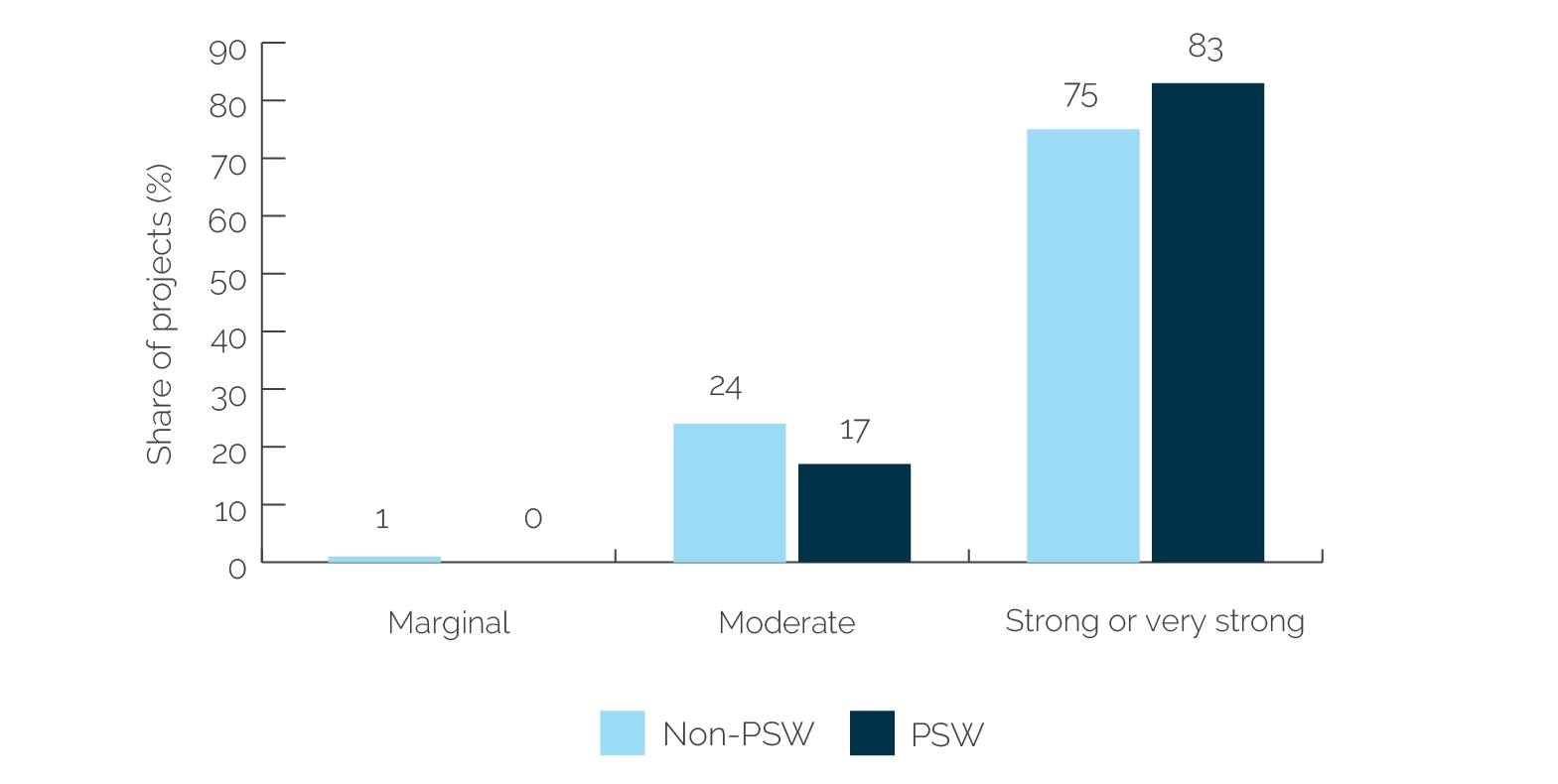

PSW projects have, ex ante, the potential to unlock markets. IFC evaluates the ex ante market impacts of its projects using the Anticipated Impact Measurement and Monitoring framework. This framework assigns projects a market potential rating that increases from “marginal” to “very strong” based on the degree to which projects deliver effects that have the potential to address important market gaps in undeveloped markets. A comparison of Anticipated Impact Measurement and Monitoring scores for a sample of PSW and non-PSW projects in the same sectors and countries shows that the share of projects with “strong” or “very strong” market potential is slightly higher in PSW projects (83 percent for PSW projects compared with 75 percent of non-PSW; figure 2.4). PSW projects often target underresourced markets and groups (for example, women or microfinance institutions) and enable investments in unexplored sectors. One example of a PSW project with a “very strong” market potential is a project in Tanzania that addresses market barriers discouraging financial institutions from serving women-led MSMEs. This project financed the first publicly placed gender bond issued by the largest bank in the country. It is expected to unlock the market for bond-financed lending for the underresourced women-owned small and medium enterprise (SME) segment through demonstration and replication effects.

Figure 2.4. Anticipated Impact Measurement and Monitoring Market Potential: PSW versus Non-PSW Projects

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: Analysis is based on a sample of 70 PSW projects and 107 non-PSW projects that were committed in the same sectors of the same countries. The difference in the Anticipated Impact Measurement and Monitoring market score of PSW-financed projects and non-PSW projects is statistically significant at a 5% threshold. (See table B.1.) PSW = Private Sector Window.

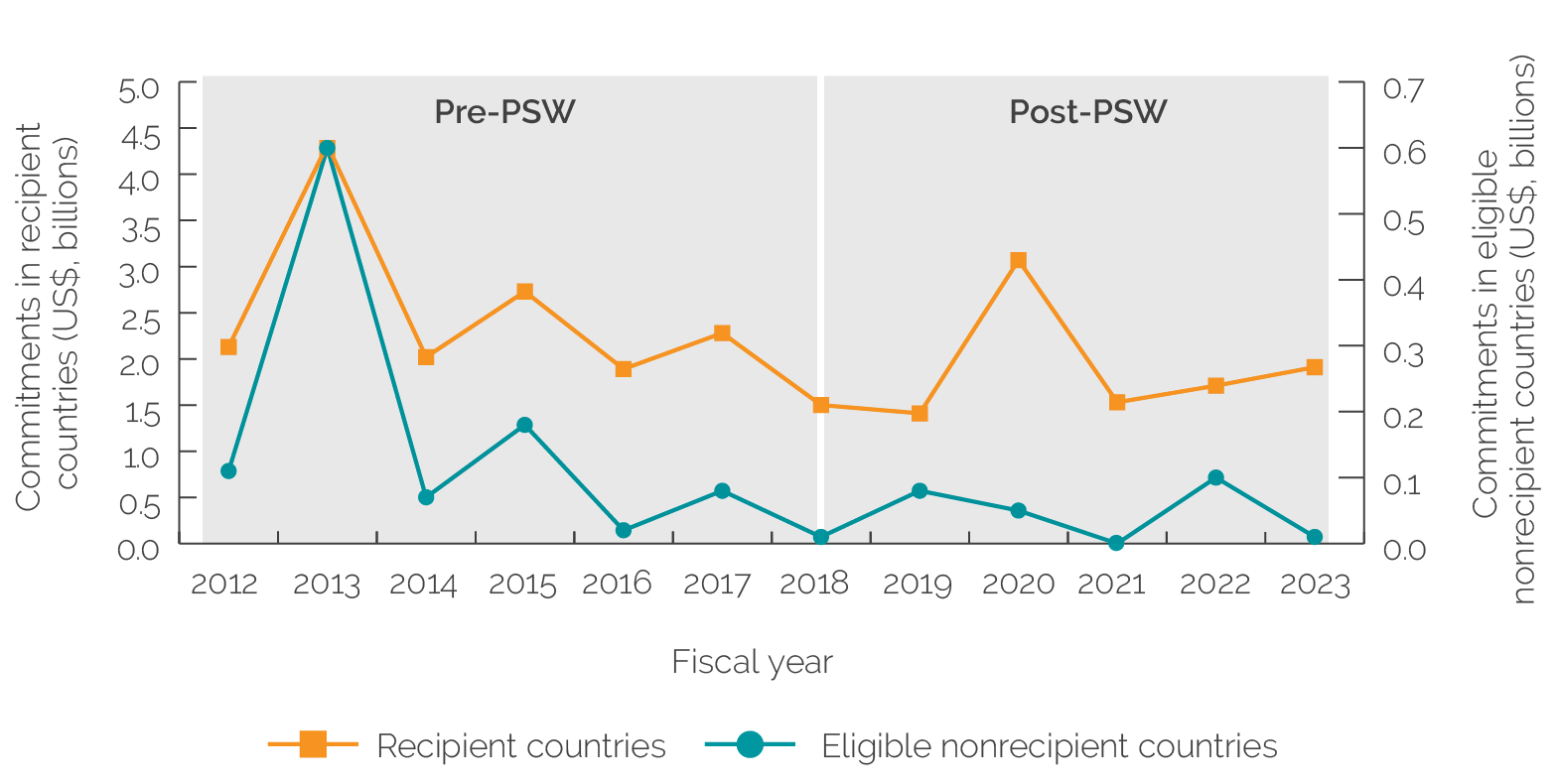

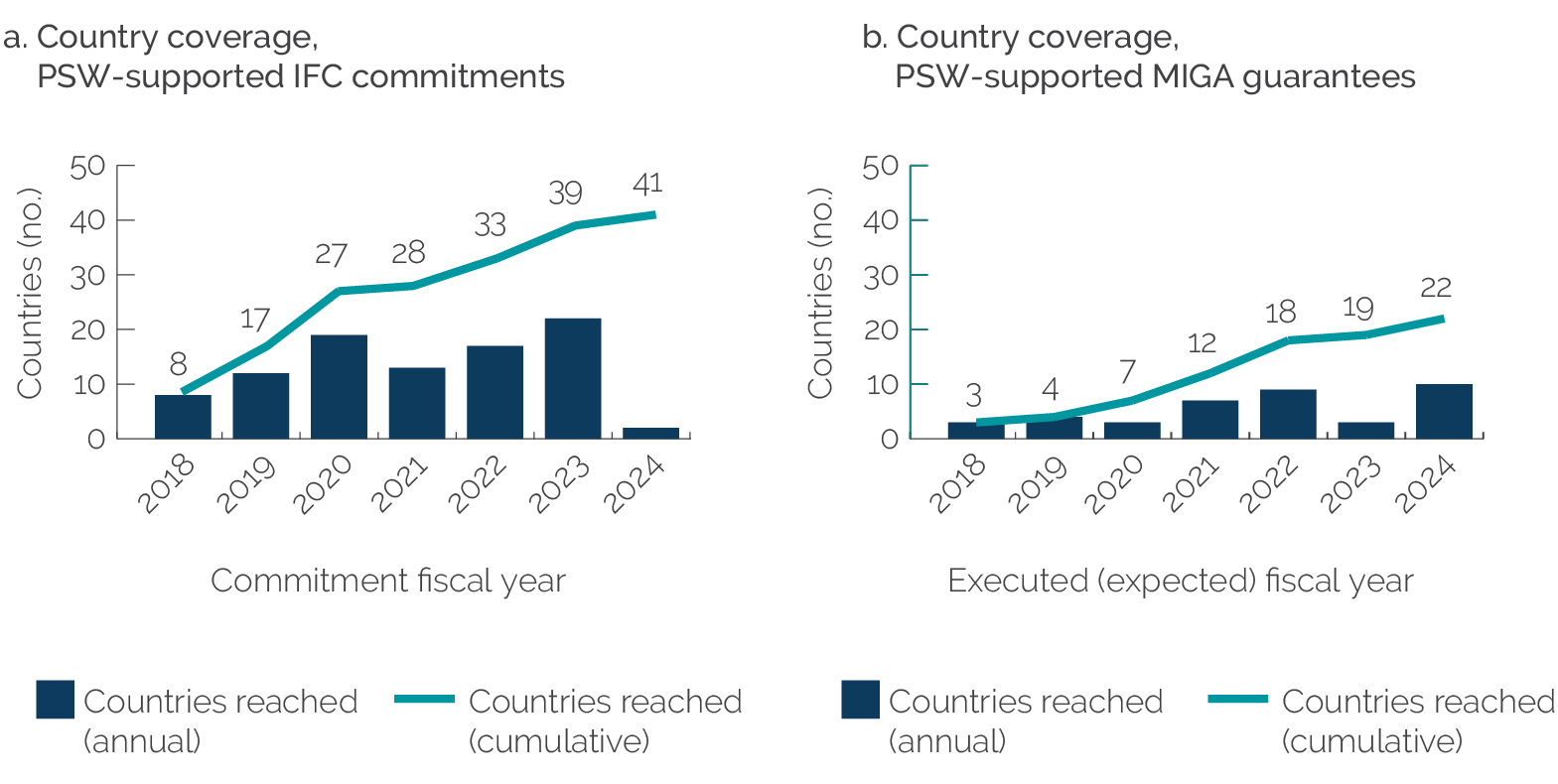

PSW has enabled IFC and MIGA to increase their investments in PSW-eligible markets, which are often underresourced by global and local capital markets. The PSW has steadily increased its country coverage, although many small economies remain uncovered. PSW support for IFC commitments has expanded steadily from 8 countries in 2018 to a cumulative total of 39 countries (figure 2.5, panel a) in 2023 (58 percent of the 67 PSW-eligible countries).2 Moreover, PSW-supported projects have already been approved but not yet committed in two additional countries, Cabo Verde and Nicaragua. There are 26 PSW-eligible countries where IFC has not had any PSW projects approved (with 15 of them having had at least one non-PSW project in the last 12 years and 11 countries having no IFC project of any kind in that period). The majority of these are small economies where the domestic private sector may not be active at a scale to enable IFC engagement.3 IFC Country Strategies for PSW-eligible countries (except Maldives) and Country Private Sector Diagnostics do not refer to the PSW as a tool to enable investments in these countries or to the constraints preventing its use. PSW support for MIGA guarantees that are already executed has also steadily increased from 3 countries in 2018 to a cumulative 19 in 2023 (figure 2.5, panel b), with guarantees already approved but awaiting execution in 3 additional countries. MIGA is active in about one-third of all PSW-eligible countries.

Figure 2.5. PSW Country Coverage

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: IFC = International Finance Corporation; MIGA = Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency; PSW = Private Sector Window.

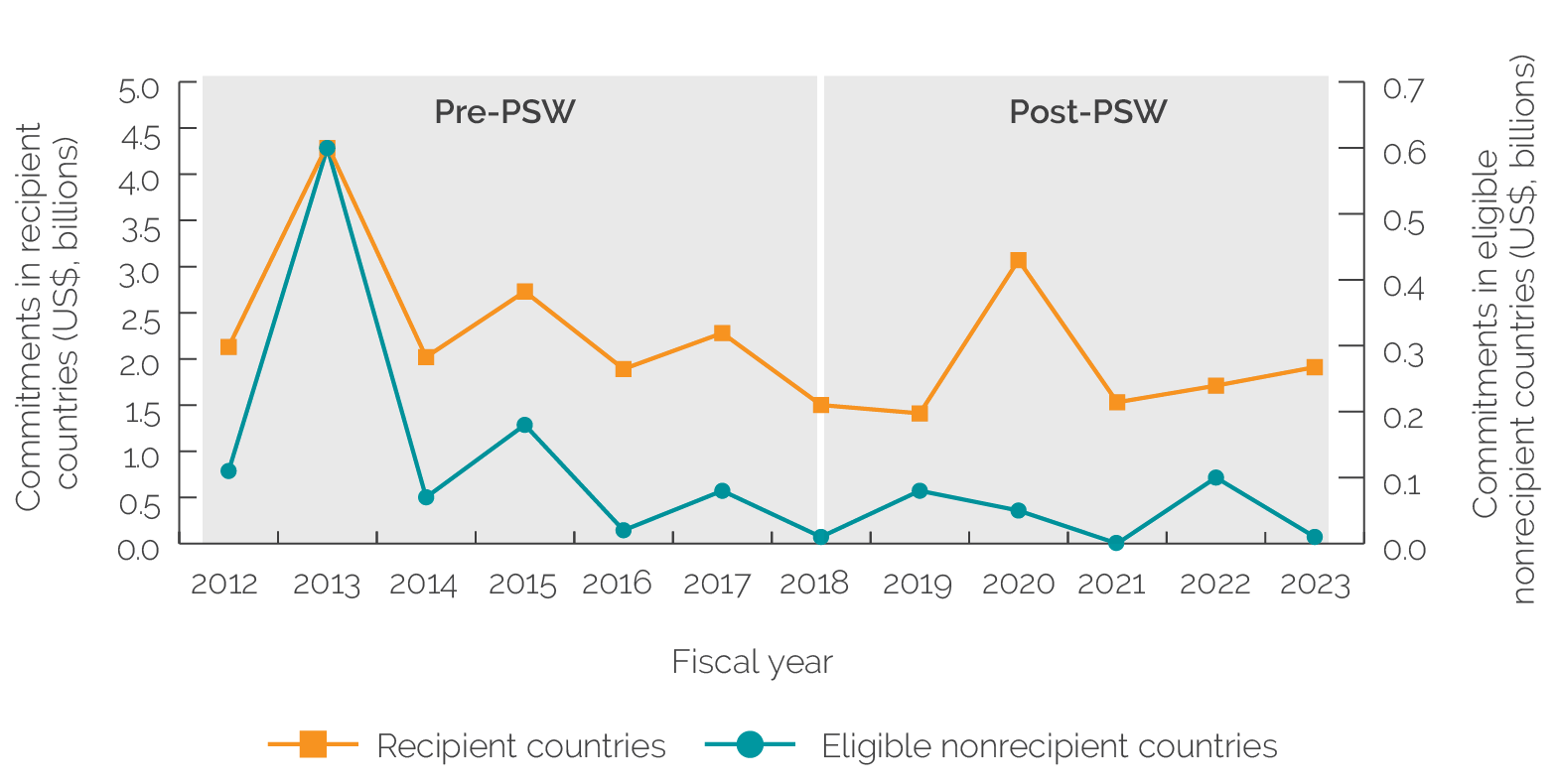

Amid multiple crises—such as the COVID-19, energy, food, and debt sustainability crises—since 2018, the PSW has allowed IFC to commit at a larger scale in eligible countries than it might otherwise have. IFC commitments were on a downward trend across PSW-eligible countries before the PSW launched in FY18. IFC’s annual average commitments dropped by 28 percent between the six years before PSW (2012–2017) and the six years after PSW (2018–23) in countries that received PSW support. By contrast, they dropped by 77 percent between the same periods in countries that did not receive PSW support (figure 2.6).4 The stark difference remains when excluding FY13 (an apparent outlier), with decreases of 16 percent in countries that received PSW support and 55 percent in countries that did not receive PSW support. IFC commitment volumes in countries with PSW projects increased especially sharply at the onset of the COVID-19 crisis in FY20. Most projects aimed at addressing the COVID-19 crisis by providing short-term financing to “keep the private sector going.” As the effects of the COVID-19 crisis started to fade, a large share of PSW projects provided local currency financing, and the tenures of PSW interventions extended. This pattern is consistent with IEG’s early-stage assessment (World Bank 2021), which found that PSW approvals increased substantially as part of the COVID-19 response.

Figure 2.6. IFC Commitments in PSW-Eligible Countries: Recipient Compared with Nonrecipient Countries

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: IFC = International Finance Corporation; MIGA = Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency; PSW = Private Sector Window.

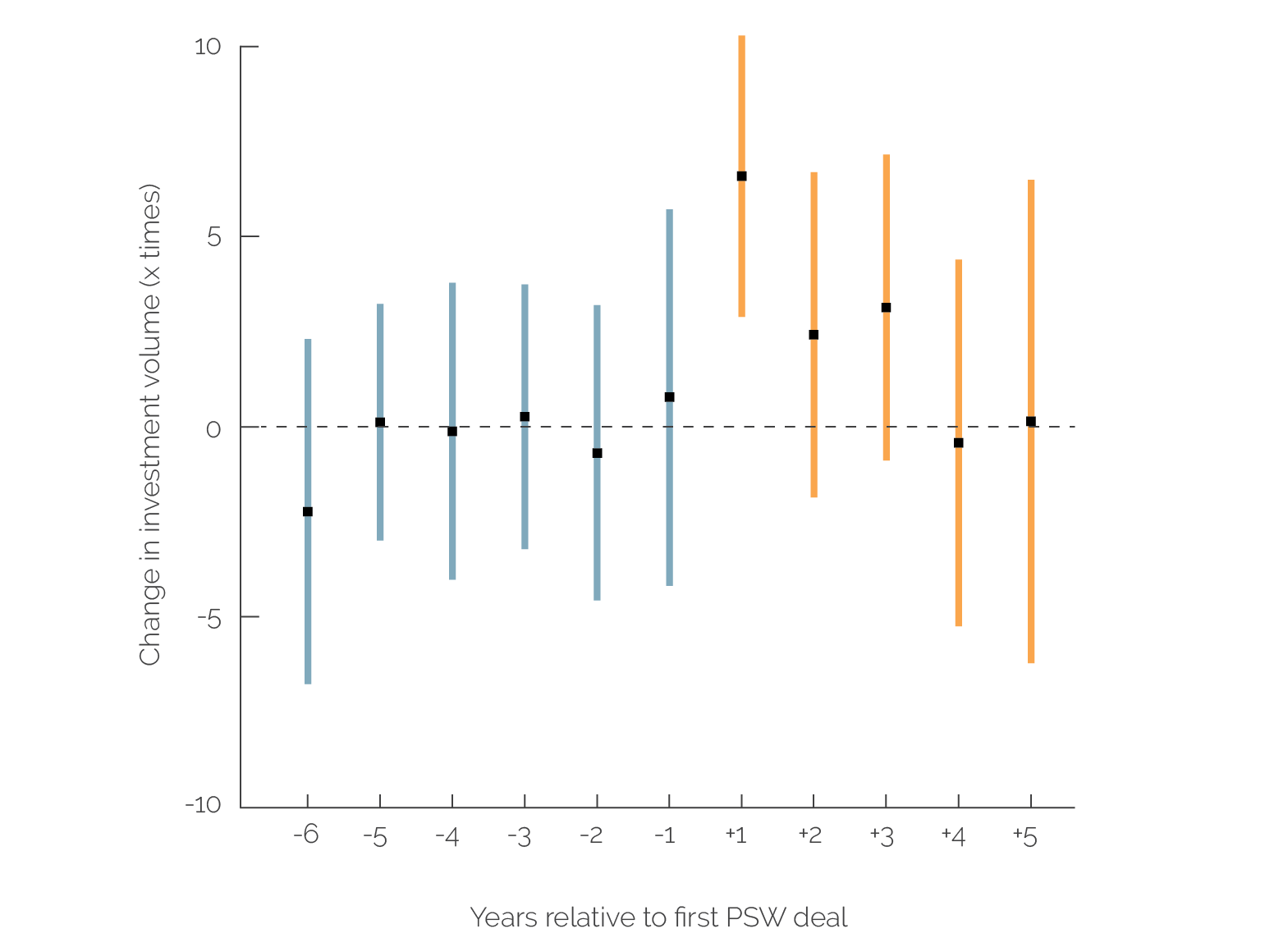

Statistical evidence confirms that the PSW has helped increase IFC engagements at the country level in PSW-eligible countries. Based on a staggered difference-in-difference analysis considering FY18 and FY23, IFC’s commitment volume in countries that received PSW was, on average, three times greater than would have been expected without PSW.5 In particular, IFC’s commitment volume increased sharply in the first FY that IFC invested in a country with PSW support and remained elevated in the subsequent couple of years, albeit to a smaller degree (figure 2.7). This scale-up in IFC commitments appears to fade in the fourth and fifth years after the first PSW usage; this finding requires further investigation beyond the scope of this evaluation. One hypothesis that could be tested is that PSW support in the early years may have demonstrated the viability of such transactions, entailing that similar projects IFC undertook in later years may have received more private capital mobilization or contributions from other partners and lower IFC own-account commitments.

Figure 2.7. Effect of PSW on IFC (Own Account) Investment Volume: Staggered Difference-in-Difference Analysis

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: Error bars show 95% confidence intervals. IFC = International Finance Corporation; PSW = Private Sector Window.

Entering Previously Unexplored Markets

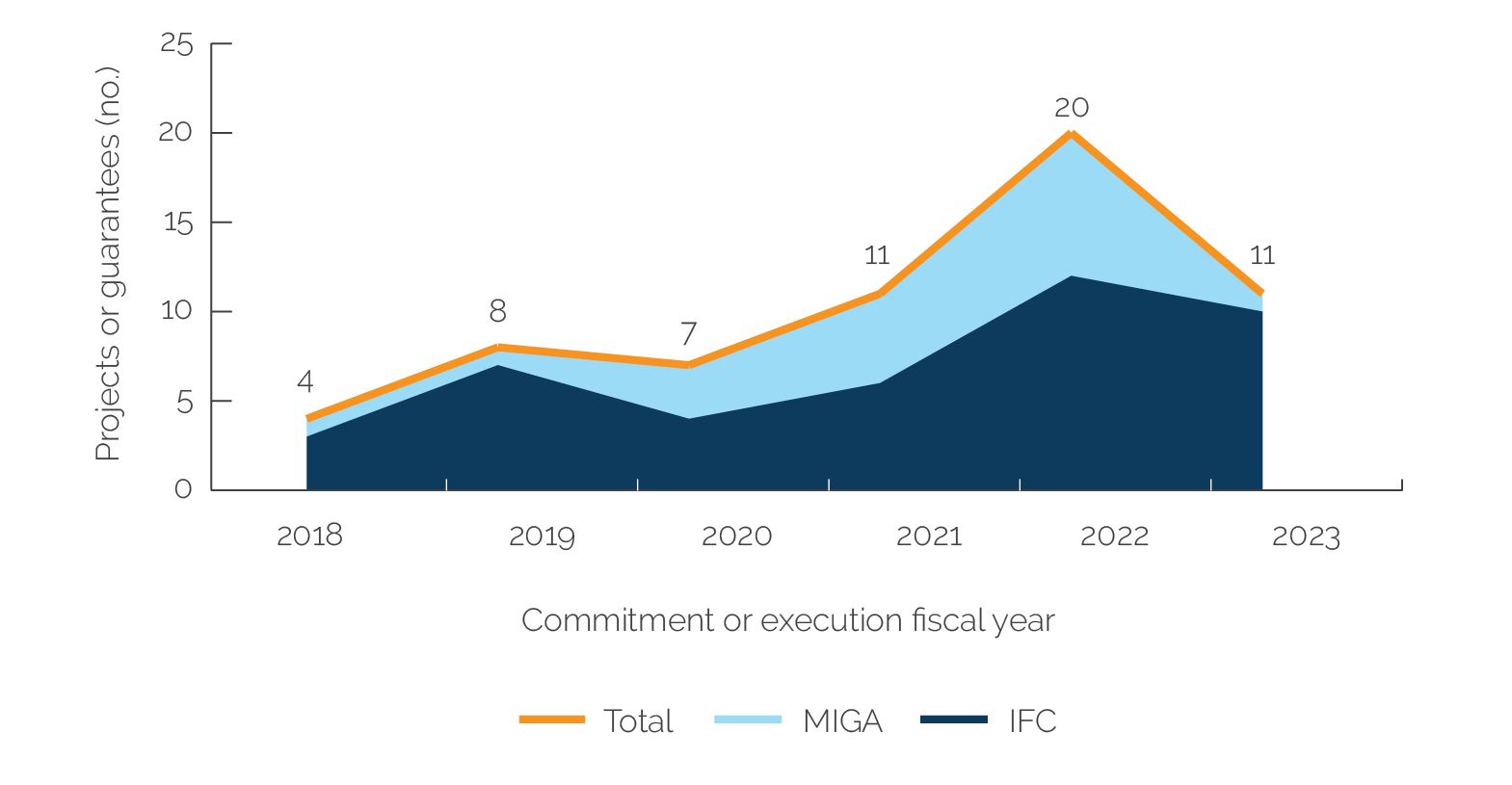

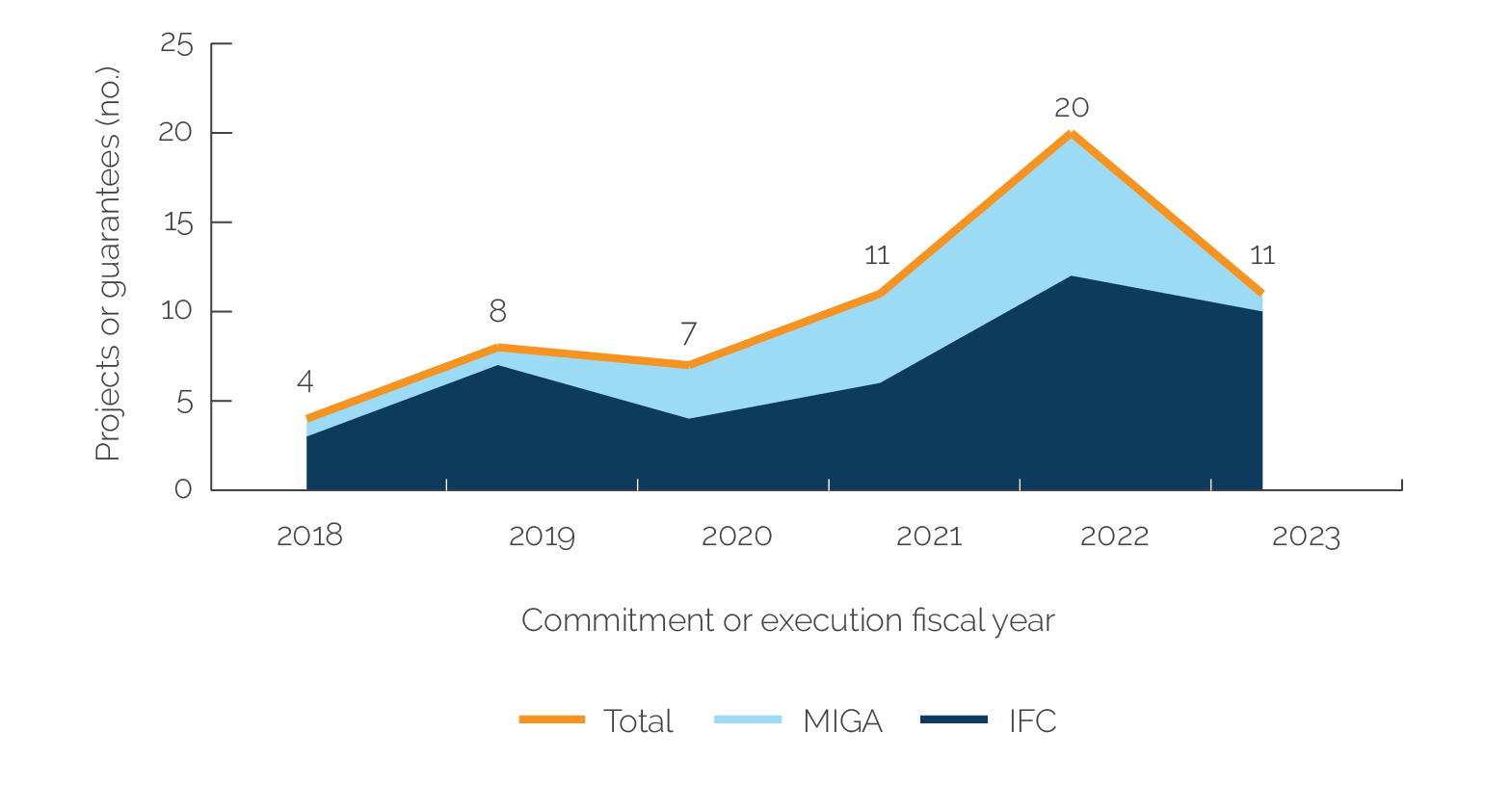

PSW support has enabled IFC and MIGA to enter new sectors in PSW-eligible countries.6 A growing number of PSW-supported projects were committed in sectors in which these institutions had not invested before PSW (figure 2.8). Overall, 17 percent of all PSW projects committed and 65 percent of MIGA guarantees executed between FY18 and FY23 were deployed in such new sectors. Examples of these projects include private equity investment in Ethiopian SMEs in FY19, thermal power generation projects in Afghanistan in FY20, infrastructure lending to a subnational government in Nigeria in FY22, investment in wholesale open-access fiber operation in Togo in FY22, and tourism infrastructure projects in Sudan in FY23. Examples of MIGA guarantees in new sectors are mobile money projects in Chad, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Niger, Uganda, and Zambia in FY22; hydropower projects in Nepal and the Solomon Islands in FY20; an industrial real estate project in Myanmar in FY21; and solar power projects in Malawi (FY19) and Burkina Faso (FY22).

Figure 2.8. PSW Projects Committed and Guarantees Executed in Sectors That IFC and MIGA Did Not Invest In Before the PSW

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: IFC = International Finance Corporation; MIGA = Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency; PSW = Private Sector Window.

Financing Riskier Transactions and Mobilizing Third-Party Capital

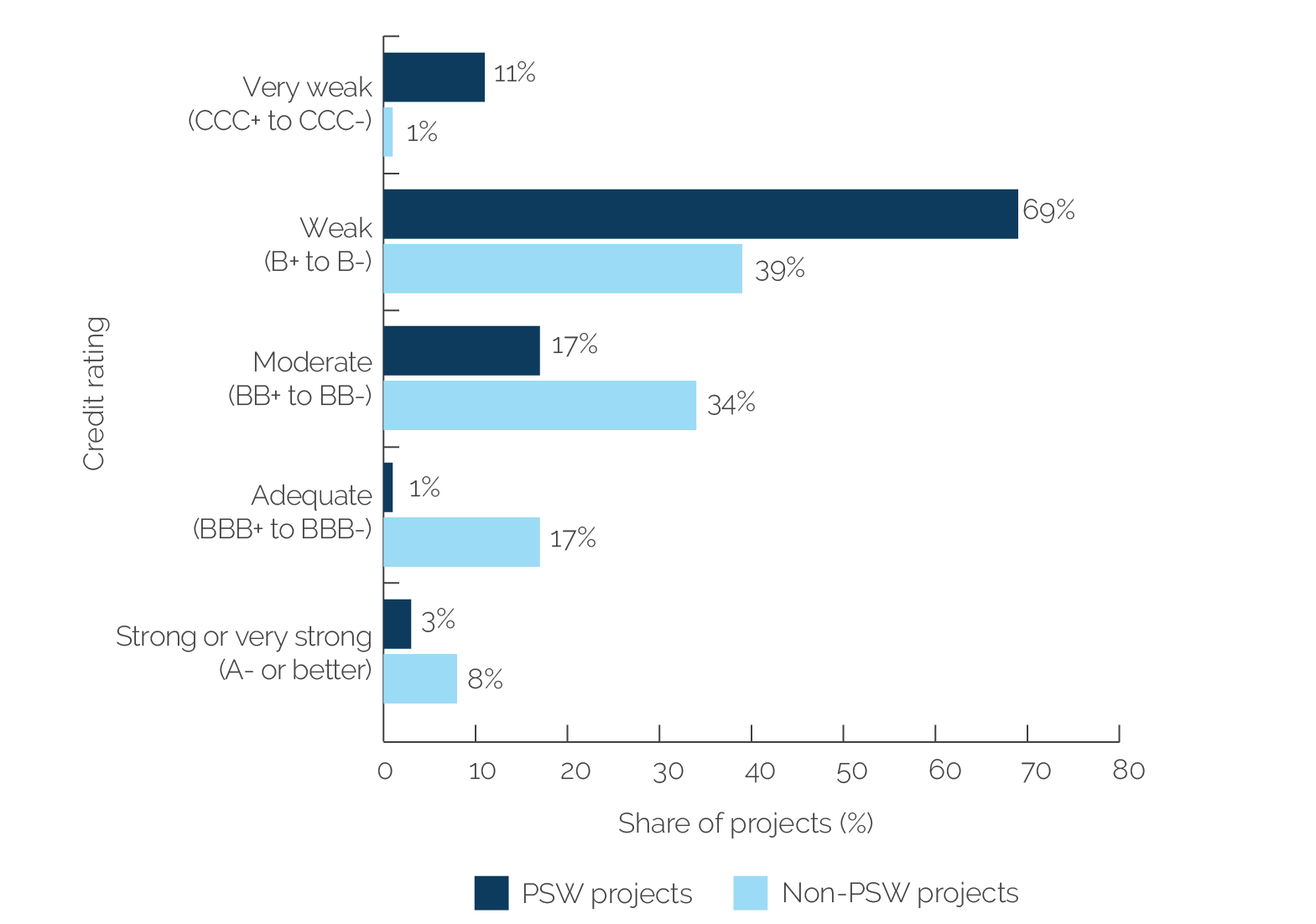

IFC uses PSW funds to finance the riskiest clients and projects. IFC uses a credit-rating system to classify the creditworthiness and risk of its investments based on the attributes of the borrower, the business environment in which the borrower operates, or the investment itself. PSW projects range on this IFC’s credit-rating scale from very strong to very weak. Based on counterfactual analysis (controlling for country and sector), PSW projects financed much riskier projects than non-PSW projects in PSW-eligible countries. A comparison of commitment volume by credit ratings for a sample of PSW projects with that of non-PSW projects committed in the same sectors of the same countries shows that the share of commitment volume in the riskiest credit-rating categories (weak and very weak) is twice as much for PSW projects as it is for non-PSW projects (figure 2.9).7

Figure 2.9. Credit Risk Rating: PSW compared with Non-PSW Projects

Sources: Independent Evaluation Group; International Finance Corporation.

Note: The ratings in parentheses reflect the equivalents of the International Finance Corporation credit-rating categories on the Standard & Poor’s rating scale. PSW = Private Sector Window.

PSW mobilizes third-party capital in transactions that investors might otherwise have refrained from. Each US dollar of PSW funds committed since inception in FY18 has blended $2.7 of additional capital from IFC and MIGA’s own account and mobilized an additional $2.0 from third-party public and private sources (table 2.2).8 Data also show that each US dollar of the institution’s own account committed mobilizes less third-party private capital in PSW-financed projects ($0.6) than in non-PSW projects ($1.4) in the same sector of the same countries (table 2.2). This reflects private investors’ reluctance to invest in PSW-financed transactions, which are perceived to be highly risky. By mobilizing capital into projects perceived as unviable, PSW helps the market generate information about these transactions’ potential viability.

Table 2.2. IFC and MIGA Investment and Third-Party Capital Mobilized by PSW Funds

|

Investment and Third-Party Capital |

PSW Financed (US$) |

Non-PSW (US$) |

|

IFC and MIGA investment and third-party capital |

||

|

IFC and MIGA O/A investment per US dollar of PSW committed |

2.7 |

n.a. |

|

Private cofinancing per US dollar of PSW committed |

1.5 |

n.a. |

|

Public cofinancing per US dollar of PSW committed |

0.4 |

n.a. |

|

Total |

4.7 |

n.a. |

|

Third-party capital mobilized in PSW-financed compared with non-PSW projects (IFC only)a |

||

|

Private cofinancing per US dollar of IFC O/A |

0.6 |

1.4 |

|

Public cofinancing per US dollar of IFC O/A |

0.3 |

0.3 |

|

Total |

0.9 |

1.8 |

Source: Independent Evaluation Group calculations based on data from the International Finance Corporation and the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency.

Note: The numbers in the “PSW Financed” column do not add to the total because of rounding errors. IFC = International Finance Corporation; MIGA = Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency; n.a. = not applicable; O/A = own account; PSW = Private Sector Window.

a. The number of PSW-financed MIGA guarantees executed to date (29) is small, and many of these were executed in sectors and countries where MIGA lacks non-PSW guarantees. Hence, the evaluation team could not build a reliably big sample of PSW and non-PSW projects to use for comparison.

Alignment of PSW Projects with IDA Special Themes

IFC and MIGA PSW projects are (ex ante) broadly aligned with the IDA special themes. PSW projects are expected to have direct objectives that lead or contribute to the PSW’s overall objectives or the IDA special themes: climate change; fragility, conflict, and violence; gender and development; governance and institutions; and jobs and economic transformation.9 The PSW documents specifically emphasize one of these themes—jobs and economic transformation—with the expectation that PSW projects would contribute to it (World Bank 2017). All 35 (nonconfidential) PSW projects in the four country case studies that we analyzed (Burkina Faso, Cambodia, Nigeria, and Tanzania) addressed one or more IDA special themes in their ex ante approval documents (table 2.3).10 Most IFC projects aim at addressing fragility and creating jobs and transforming economies, whereas MIGA projects aim mostly at addressing fragility and climate change. A PSW project in Tanzania exemplifies how PSW projects aim to address broad development objectives. IFC provided funds to a major Tanzanian financial institution to on-lend to MSMEs to support creating a conducive environment for economic recovery and growth from the pandemic. It aimed to stimulate economic activity by ensuring that these enterprises could continue their operations during the crisis. This, in turn, was expected to contribute to job retention, income generation, and overall economic stability. The project’s market creation aspect aligns with the broader goal of positioning the private sector for postpandemic recovery and reducing the time it takes for vulnerable populations to regain income-earning opportunities.

Table 2.3. Contribution of PSW Projects in Country Cases to IDA Special Themes

|

IDA Special Theme |

IFC PSW Projects (no.) |

Share of IFC Projects (%) |

MIGA Projects (no.) |

Share of MIGA Projects (%) |

|

Fragility, Conflict, and Violence |

20 |

67 |

5 |

100 |

|

Jobs and Economic Transformation |

18 |

60 |

0 |

0 |

|

Gender and Development |

13 |

43 |

2 |

40 |

|

Climate Change |

6 |

20 |

5 |

100 |

|

Governance and Institutions |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: Number of projects: IFC PSW = 30, MIGA = 5. IDA = International Development Association; IFC = International Finance Corporation; MIGA = Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency; PSW = Private Sector Window.

The quality of indicators used to assess alignment with the IDA special themes varies. The climate change PSW projects included outcome indicators directly aligned with this theme (for example, reduction in carbon dioxide emissions resulting from the project). The evidence for supporting gender, jobs, and economic transformation was mostly indirect, through indicators such as improving access to finance for underresourced SMEs, improving access to capital for women-owned businesses, and increasing the number of loans provided to women-owned businesses. Five projects contained direct employment indicators (such as “number of women employed”).11

- According to the project documentation for projects 14595, 14574, and 14583.

- Three countries eligible for the Private Sector Window (PSW; Eritrea, the Syrian Arab Republic, and Zimbabwe) are not included in this count of 67 PSW-eligible countries. According to the list of PSW-eligible countries, these countries are tagged as “inactive”—that is, they have no active International Development Association (IDA) financing because of protracted nonaccrual status.

- These 26 countries are the Central African Republic, the Comoros, the Republic of Congo, Djibouti, Dominica, Fiji, The Gambia, Grenada, Guinea-Bissau, Guyana, Honduras, Kiribati, Lesotho, Malawi, Maldives, the Marshall Islands, the Federated States of Micronesia, Papua New Guinea, São Tomé and Príncipe, Sierra Leone, the Solomon Islands, Somalia, Sudan, Tonga, Tuvalu, and Vanuatu. These 26 countries collectively account for 7 percent of the total GDP of all 67 PSW-eligible countries.

- Calculation excludes regional projects

- Analysis controls for income levels, regional factors, and duration since first PSW-supported commitment.

- “New sectors” refers to sectors (at the secondary sectoral classification level) that the International Finance Corporation (IFC) and the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA) had never invested in within a specific PSW-eligible country before PSW.

- The difference is statistically significant at the 5 percent level.

- This estimate is based on the subset of the IFC and MIGA PSW portfolio for which we have data on capital mobilization, but it is broadly consistent with the estimates reported in the 20th Replenishment of IDA (IDA20) PSW Mid-Term Review.

- For the IDA20 cycle, Human Development was added, the Governance and Institutions theme was dropped, and the other four special themes remained the same. We did not analyze the Human Development theme, which was added only in IDA20, because only one year has passed in this cycle.

- For our review, we counted a project as addressing a specific special theme if it was mentioned in the project description or development impact section in Board approval documents or there was any indicator tracked that was related to the special theme

- This contribution to jobs and economic transformation was demonstrated by the employment and economy effects and competitiveness (number of new entrants) indicators tracked as part of the Anticipated Impact Measurement and Monitoring indicators. A larger percentage of the projects (mostly the Financial Institutions Group) had indirect effects on supporting the jobs and economic transformation agenda by improving access to finance for under-resourced micro, small, and medium enterprise businesses or housing finance. The rationale was that improving finance to micro, small, and medium enterprises would in turn increase job creation because these businesses are “important sources of job creation.”