Financial Inclusion

Chapter 2 | Relevance of World Bank Group Support for Financial Inclusion—Doing the Right Things

Highlights

This chapter assesses the relevance of the World Bank Group’s support to financial inclusion (whether the Bank Group is doing the right things) at three levels—global, national, and instrument.

Although it finds some evidence of relevance at each of these levels, there was an imbalance in support for access over other inclusion goals and for credit over other financial services. Bank Group financial inclusion interventions only recently evolved toward supporting usage.

At the global level, the alignment of Bank Group activities with the Universal Financial Access 2020 strategy and framework and with global priorities was strong. By focus area, Bank Group support concentrated on access goals and strengthening institutions. Support on financial access drivers focused on diversifying access points.

At the country level, over time, the Bank Group’s engagement and strategies grew increasingly aligned with countries’ financial inclusion goals and focused more on the inclusion of women and underserved populations. The alignment of the Bank Group’s country strategies and activities with national financial inclusion strategies and priorities varied substantially based on different levels of country client commitment, capability, and access to alternative sources of support. Where the World Bank did not lead support in defining or formulating the national financial inclusion strategies, it did support aspects of its implementation.

The Bank Group’s choice of instruments was broadly aligned with different objectives and services with some gaps. World Bank development policy operations were used commonly to all financial services, and investment lending focused on credit. International Finance Corporation investments were strongly focused on credit; the International Finance Corporation used advisory services to support credit but also to support payments and sometimes insurance.

World Bank advisory services and analytics and International Finance Corporation advisory services played important roles in upstream engagements on policy, regulation, and institutional capacity building. The Financial Sector Assessment Program’s financial inclusion technical notes helped guide the formulation and implementation of inclusion strategies in several client countries.

The number of Bank Group projects with a gender component increased sharply in fiscal year 2018, potentially in response to the 2016 Gender Strategy. However, a minority of financial inclusion projects target other excluded groups.

This chapter assesses the relevance of the Bank Group’s support for financial inclusion in the period FY14 to mid-FY22. It assesses relevance at three levels—global, country, and instrument. The chapter assesses global relevance in terms of the alignment of Bank Group activities with the UFA2020 initiative; evolving global priorities and needs, including the global shift toward payment services and digital services, especially in response to COVID-19; top barriers to inclusion; and related corporate priorities on the topic. It assesses relevance at the country level in terms of the alignment of Bank Group country strategies and activities with national strategies and priorities on financial inclusion. It assesses relevance at the instrument level in terms of the alignment of the Bank Group’s selection of instruments with financial inclusion objectives at the global and country level and in terms of consistency of financial services with country needs.

Global Relevance

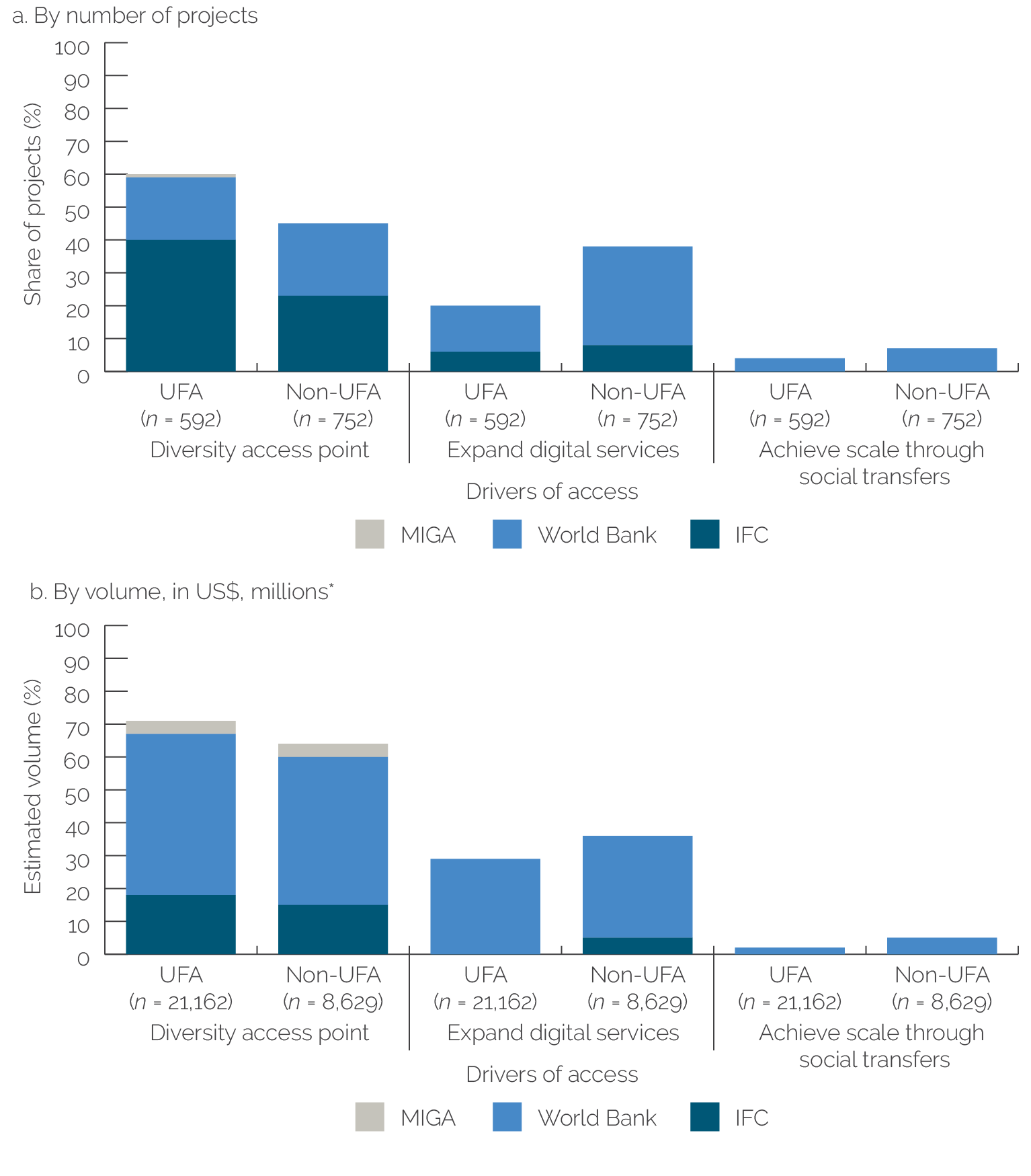

The Bank Group’s activities were highly relevant to the UFA2020 strategy and framework. The UFA2020 Action Framework provided a broad structure for the Bank Group’s financial inclusion work focusing on three drivers of access: (i) expanding digital payment instruments, (ii) diversifying access points, and (iii) achieving scale through social transfers. It also identified two enablers: building an enabling regulatory environment and ramping up the payments and information and communication technologies infrastructure. Bank Group activities were relevant to these drivers and enablers. In the 25 UFA2020 priority countries, work on the drivers focused heavily on diversifying access points by both project number and volume (figure 2.1). Even in nonpriority countries, diversifying access points received the majority of financing by volume. For enablers, twice the financing went to building the regulatory enabling environment compared with ramping up the payments and information and communication technology infrastructure. The Bank Group focused on countries where the most excluded people lived rather than those with the lowest rates of inclusion.

Figure 2.1. Projects Supporting Three Universal Financial Access 2020 Drivers

Source: Independent Evaluation Group portfolio review and analysis.

Note: The figure includes estimated financing by the World Bank, IFC, MIGA, IFC advisory, and World Bank advisory services and analytics. Figures for unevaluated projects and advisory services and analytics are projected based on stratified random samples. Dollar volume figures include commitments and expenditures. IFC = International Finance Corporation; MIGA = Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency; UFA = universal financial access.* To estimate the total volume related to financial inclusion in development policy operations and other multicomponent projects, the projects’ committed dollar value amount reported in project documentation was allocated proportionally among components (for example, prior actions for development policy operations). Only components related to financial inclusion were considered. Where a component had multiple subcomponents, the committed amount was allocated proportionally to those subcomponents addressing financial inclusion.

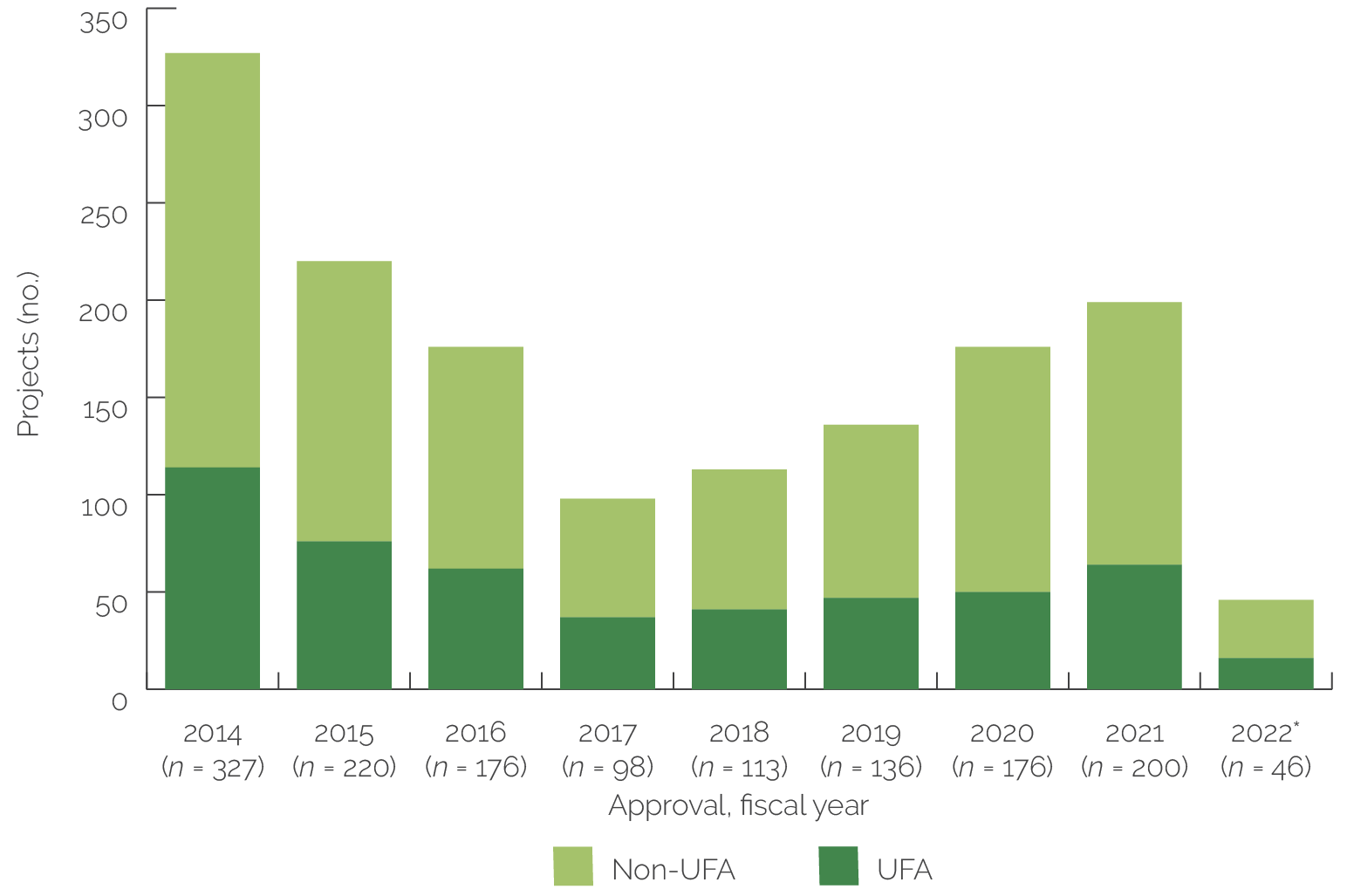

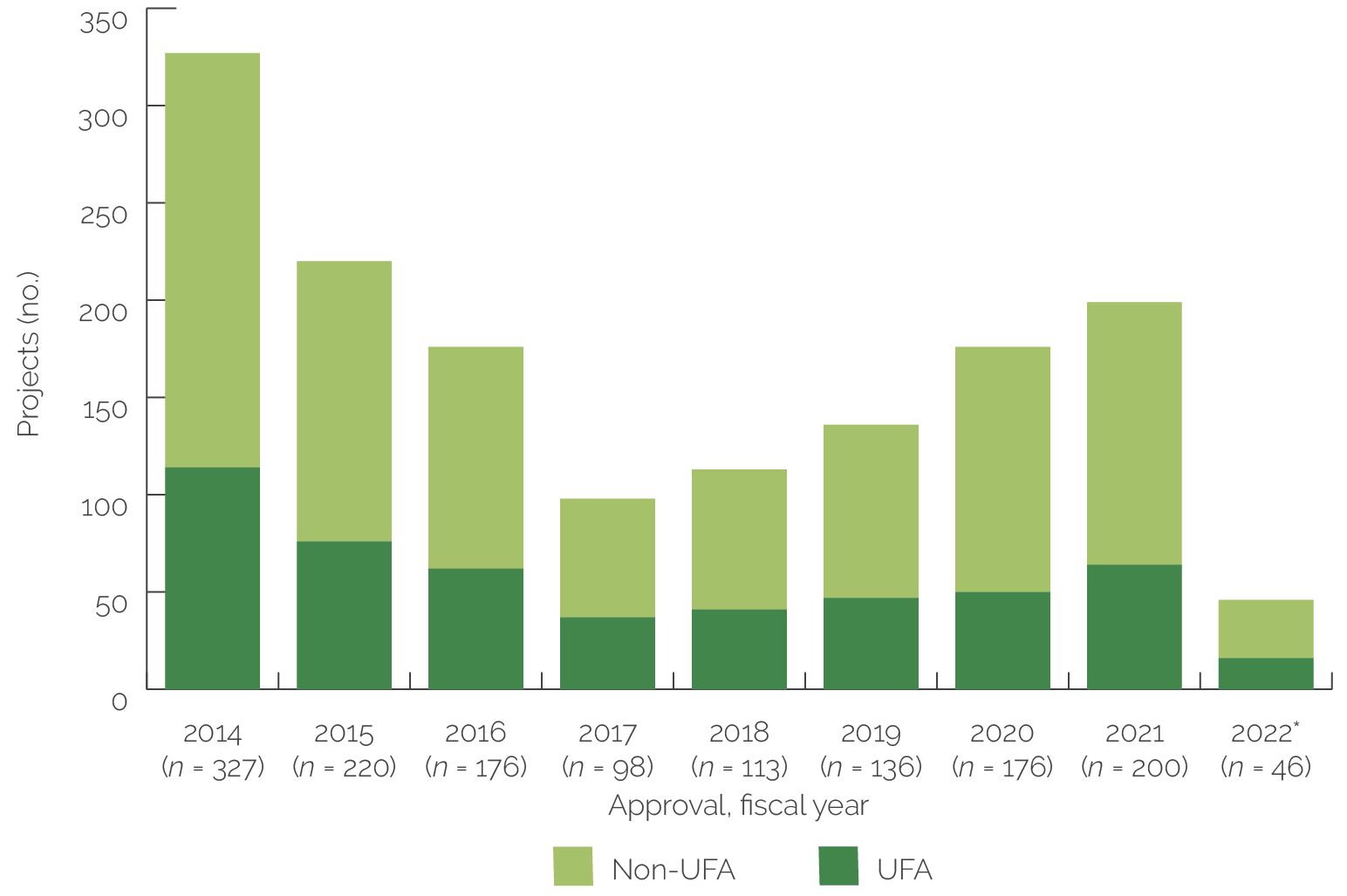

Bank Group global support for financial inclusion was high in the early years of the evaluation period, in line with the announcement of the UFA2020 initiative, and increased again during the COVID-19 response. Although the Bank Group initially centered its UFA2020 strategy on 25 countries where 73 percent of all financially excluded people live, over time it extended its universal financial access engagement well beyond this initial focus. Throughout the period, the Bank Group engaged substantially with non-UFA2020 countries, more so during COVID-19 (figure 2.2). IFC’s Base of the Pyramid Platform and Fast-Track Facility (complemented by a MIGA guarantee)1 exemplify the intense response. By the end of the evaluation period, the Bank Group reported being engaged on the universal financial access agenda with over 100 countries (World Bank 2018b). Perhaps because UFA2020 had focused on larger opportunities for gains in access, the average project size was larger in the 25 priority countries than in other countries. Therefore, although many projects in the financial inclusion portfolio (64 percent) focused on non-UFA2020 countries, most of the commitment value (71 percent) was in the UFA2020 priority countries.

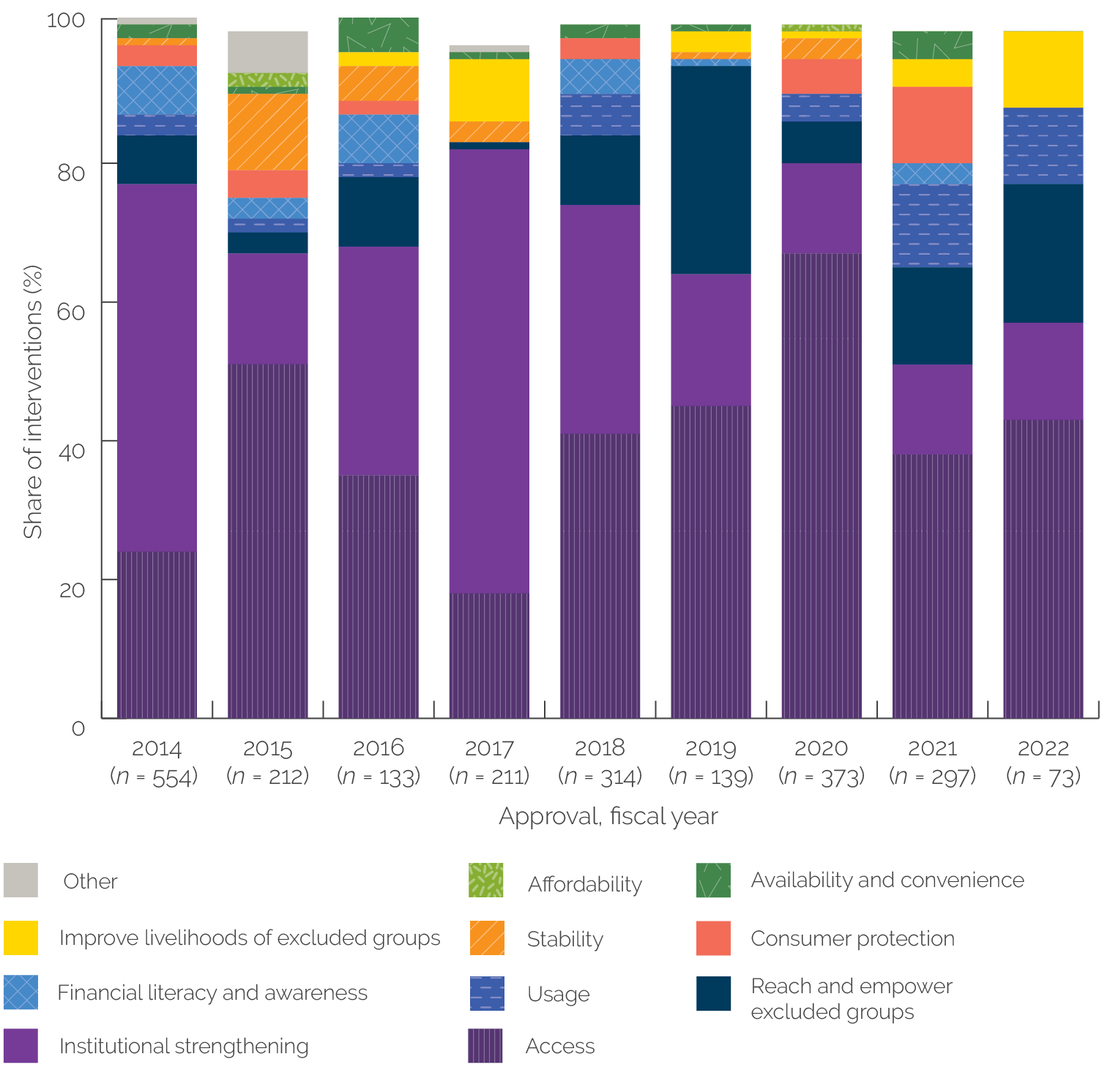

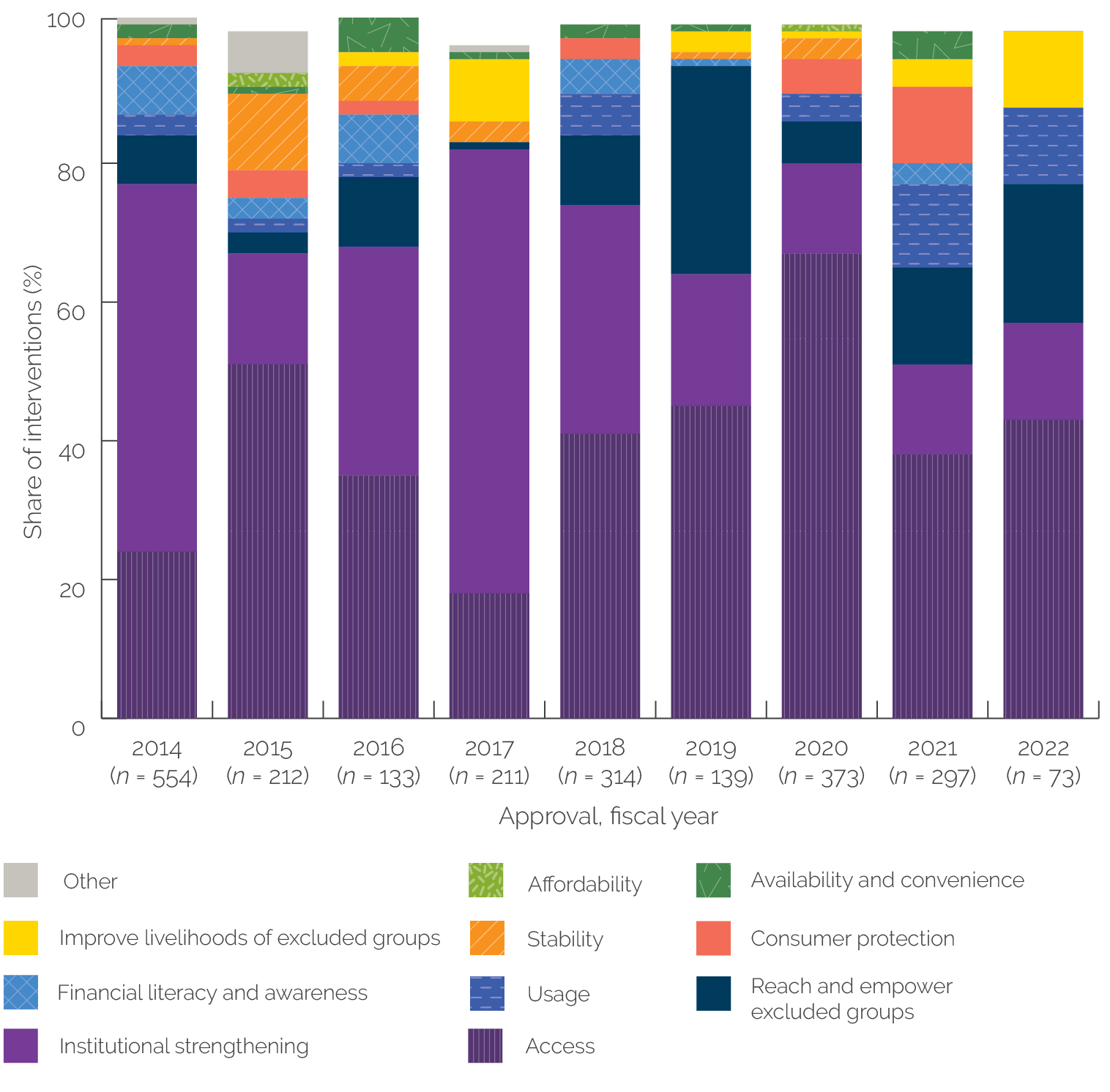

By area of focus, Bank Group support concentrated largely on access goals and institutional strengthening, as defined in UFA2020, evolving only recently toward usage. Project interventions with access goals accounted for 70 percent of the commitment value of the portfolio and 41 percent of interventions during the evaluation period (figure 2.3). Interventions aimed at institutional strengthening accounted for 15 percent of total commitments and 32 percent of interventions. By contrast, very few projects had an explicit objective of enhancing usage, except in FY21–22. Most years, less than 5 percent of interventions had a usage objective. With some exceptions, reaching, empowering, or improving the livelihoods of excluded groups was rare as an objective in most years of the portfolio but expanded notably in FY21–22.

Country experiences suggest that, even when the main emphasis of support is on access, other objectives may coexist. For example, in Mozambique, the Bank Group–supported NFIS had a headline target of 40 percent of the population with access to physical or electronic financial services by 2018 and 60 percent by 2022. However, NFIS had three pillars that reflect thinking about use, rather than simply physical access: (i) access to and use of financial services, (ii) strengthening of financial infrastructure, and (iii) consumer protection and financial education. In Indonesia, despite an important emphasis on access, Bank Group financial inclusion interventions were aligned with reaching the most vulnerable populations and encouraging their use of financial services. A World Bank ASA project aimed to improve the financial education of migrant workers, the savings of older people, digital payments, and gender equality. IFC AS supported insurance and digital services with the aim of reaching excluded rural people through the agriculture sector.

Figure 2.2. Financial Inclusion Projects by Fiscal Year and Country Universal Financial Access 2020 Focal Status

Source: Independent Evaluation Group portfolio review and analysis.

Note: UFA = universal financial access.* Fiscal year 2022 considers projects approved by December 31, 2021 (or effective by December 31, 2021, for Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency projects).

Projects emphasizing usage of financial accounts—a vital component of financial inclusion—became common only late in the evaluation period. Although project interventions with access goals during the evaluation period accounted for 70 percent of the commitment value of the portfolio, only less than 5 percent had usage-enhancing objectives. However, usage objectives expanded significantly during the later years of the evaluation period—from 2 percent in FY15 to 12 percent in mid-FY22. In Indonesia, an IFC project in support of the use of DFS launched large-scale awareness campaigns, using advanced data analytics to improve targeting, outreach, and project design. In Brazil, IFC joined a mobile payment provider to support access to and use of electronic payments through mobile money rollouts targeting beneficiaries of the Brazilian government’s social welfare payment program. The program monitoring went beyond access to track account usage, including noncash transactions.

Figure 2.3. Financial Inclusion Portfolio by Area of Focus, by Interventions

Source: Independent Evaluation Group portfolio review and analysis.

Note: Distribution is projected according to expansion factors calculated using a stratified random sample of World Bank advisory services and analytics and unevaluated projects. The sampling framework considered institution, instrument, Region, and country income level as strata. Caution: Unmodeled variables (not considered in the strata) may result in biased estimates. Approval year is an unmodeled variable. Fiscal year 2022 considers projects approved by December 31, 2021 (or effective by December 31, 2021, for Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency projects).

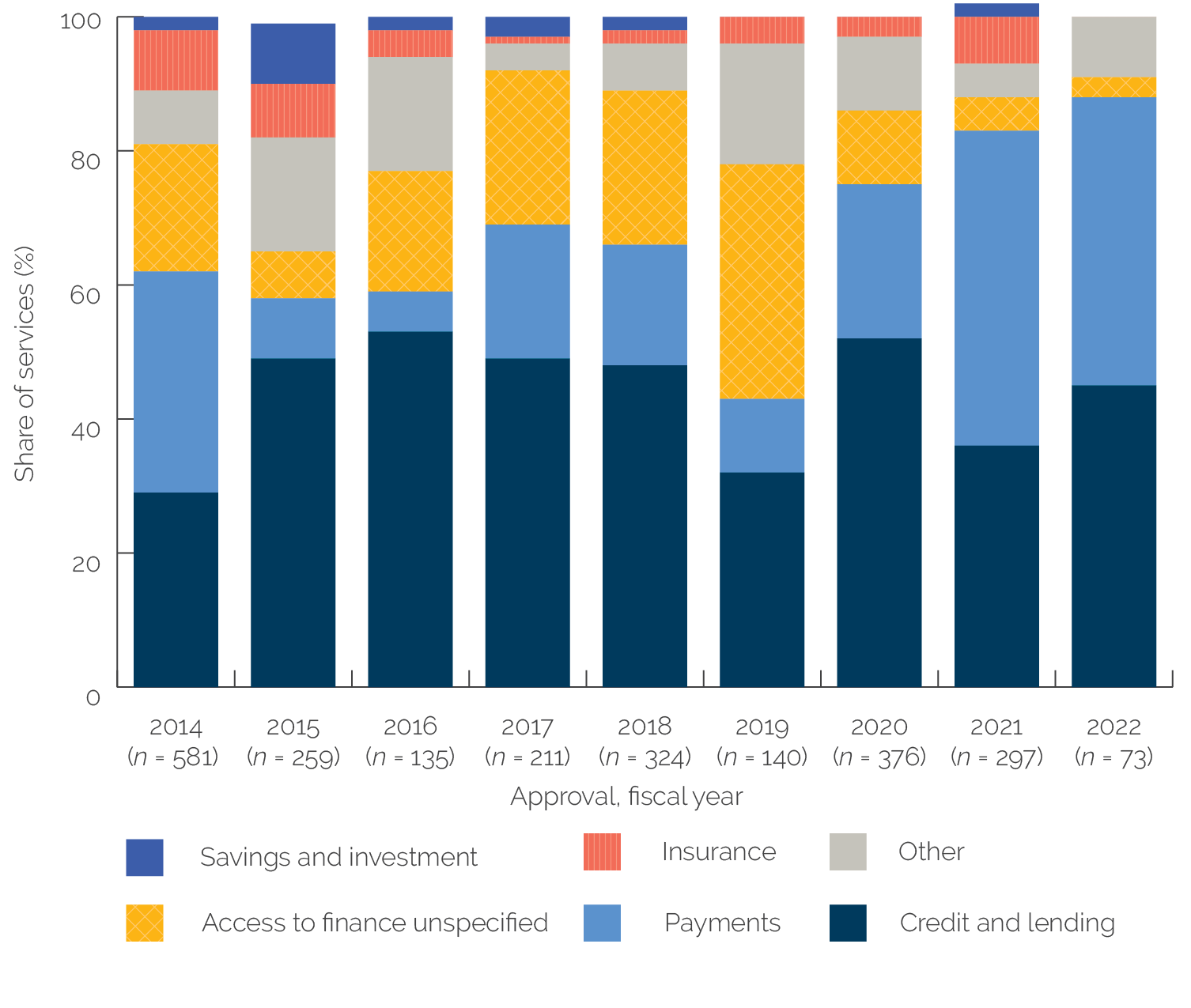

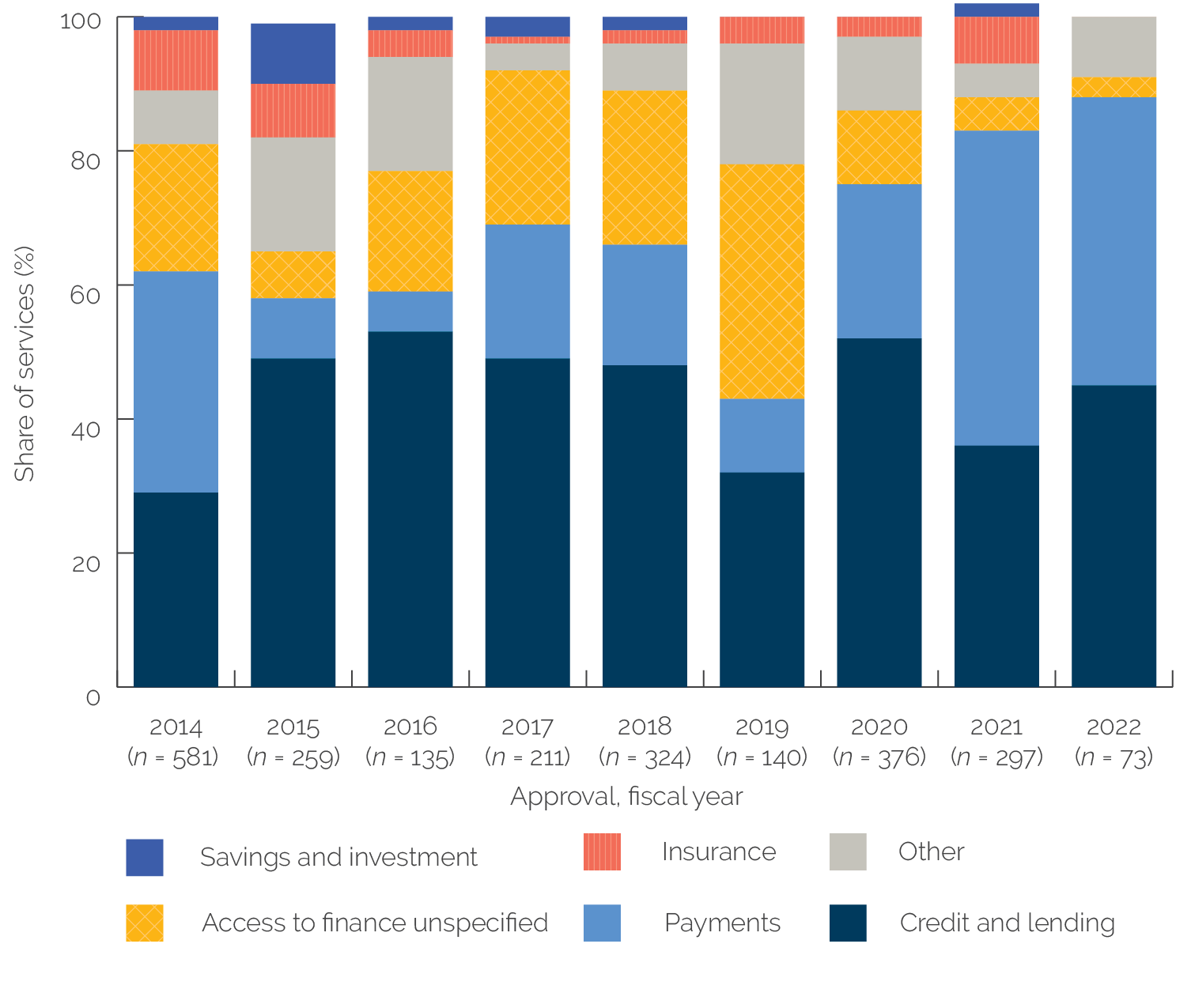

Over time, the Bank Group financial inclusion portfolio also evolved and adapted to focus more on payment services and DFS—a trend that accelerated in response to COVID-19. The number of services focused on payments increased strongly over the period, especially from FY19 onward (figure 2.4). Along with this jump, projects explicitly identified as responding to COVID-19 were about twice as likely as non–COVID-19 projects to support payment services. Emphasis on G2P payments, including online payments, sharply increased in the COVID-19 response portfolio. This change is important in part because payment interventions are the only type focused on the usage objective.

Figure 2.4. Financialand inclusion Services Supported by Approvand l Year

Source: Independent Evaluation Group portfolio review and analysis.

Note: Distribution is projected according to expansion factors calculated using a stratified random sample of World Bank advisory services and analytics and unevaluated projects. The sampling framework considered institution, instrument, Region, and country income level as strata. Caution: Unmodeled variables (not considered in the strata) may result in biased estimates. Approval year is an unmodeled variable. Fiscal year 2022 considers projects approved by December 31, 2021 (or effective by December 31, 2021, for Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency projects).

Support for payment services evolved over the evaluation period. Traditionally, it was channeled through banks, but more recently, support has been directed to both banks and NBFIs, which can benefit consumers by enhancing competition. Emphasis on payment services grew in close association with the rapid digital transformation that is changing conventional notions about consumer behaviors and preferences. By dollar volume, most of the Bank Group’s financial support for payments was delivered through development policy operations (DPOs), but by number of services, 55 percent of support for payments was provided through ASA.2 In Mozambique, the World Bank supported establishing a single national network that unified the electronic payment system—allowing a reduction in the cost of interbank transactions—and measures that made agent and branch banking more accessible to the rural population. IFC provided AS to a mobile operator that supported a rapid expansion of mobile services to excluded people, including in rural areas.

In line with global trends, since FY17, the share of DFS in the portfolio has steadily increased, with a discontinuous jump in FY21, the first full year of the COVID-19 response. In FY21 and mid-FY22, support for DFS accounted for over 60 percent of services in the portfolio. DFS are valued for their low transaction costs, for their ability to reach remote areas without having to transport cash, and for enabling financial transactions without human contact (McKinsey & Company 2016; Pazarbasioglu et al. 2020). Although they introduce risks that need to be carefully managed, they have been increasingly understood by the Bank Group and clients to compose the primary core instrument for increasing financial inclusion. Most World Bank DFS support focuses on strengthening the enabling environment, primarily through ASA and DPOs. Forty-one percent of World Bank support to DFS was through ASA compared with 14 percent for traditional services, and 70 percent of DPOs in dollar volume focused on DFS compared with 29 percent on traditional means. For example, in Egypt, the World Bank used a development policy loan (DPL) to support a new fintech law for NBFIs. This and revisions to the banking law gave a mandate to the Egyptian financial regulatory authority to regulate NBFI digital activities and clarified the licensing and regulatory requirements for NBFIs offering digital services while enhancing consumer protection. Complementary ASA further supported DFS in Egypt, including measures to reform the national payment system and strengthen consumer financial protection and literacy. A concurrent IFC MSME supply chain finance project supported electronic payment acceptance by small merchants. In the Philippines, a World Bank investment project helped finance the creation of digital payment mechanisms during COVID-19. In Mozambique, the World Bank delivered a seminal analytic report, Mozambique Digital Economy Diagnostic (World Bank Group 2019), mapping out bottlenecks and key recommendations for achieving a digital economy.

The need both to avoid person-to-person interactions and to deliver benefits to those most at risk from the economic consequences of COVID-19 increased clients’ drive for improved and expanded digital payment systems and services. This included new services, enabling laws and regulations, and digital infrastructure, including new or improved payment platforms. For example, in Bangladesh, the crisis response during the COVID-19 pandemic included support for digitalizing government payments and channeling them through new or existing payment accounts. In Mozambique, World Bank support for both cyclone and COVID-19 relief consciously promoted financial access by channeling government payments digitally through bank and mobile network accounts.

IFC investments, although focused on traditional financial institutions, commonly used AS to support their clients’ offering of digital services, with a strong focus on excluded populations. Key aims were institutional strengthening, developing or expanding new products, developing new or improved strategies, and strengthening DFS capacity within banking institutions. The majority of DFS support has been focused on lower-middle-income countries and supporting regions with a large, excluded population, such as those in South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa.

The number of Bank Group projects with a gender component increased sharply in FY18, potentially in response to the 2016 Gender Strategy. More projects explicitly targeted women’s use of financial services and tracked it with disaggregated indicators. After the spike in FY18, the number of projects with gender components plateaued at approximately twice their historical level (about 47 percent of projects compared with a prior 20 percent) in subsequent years. We found this increased focus on gender at the country level as well.

However, a minority of financial inclusion projects target other excluded groups. About one-quarter of projects had rural components or objectives with a marginal increase over time. Additionally, 7 percent of all projects identify refugees and forcibly displaced people, religious minorities, vulnerable children, and people with severe disabilities as their beneficiaries. For example, in Colombia, IFC delivered an advisory project to develop and test a value proposition and a viable product for the displaced Venezuelan population. Indigenous peoples are mentioned in 1 percent of financial inclusion projects, and specific age-groups (youth and older adults) are mentioned in 4 percent of the portfolio. In Guatemala, IFC delivered investments to provide access to credit in several frontier regions including large Indigenous populations. The share of projects targeting specific vulnerable groups is higher in the World Bank’s portfolio compared with IFC projects.

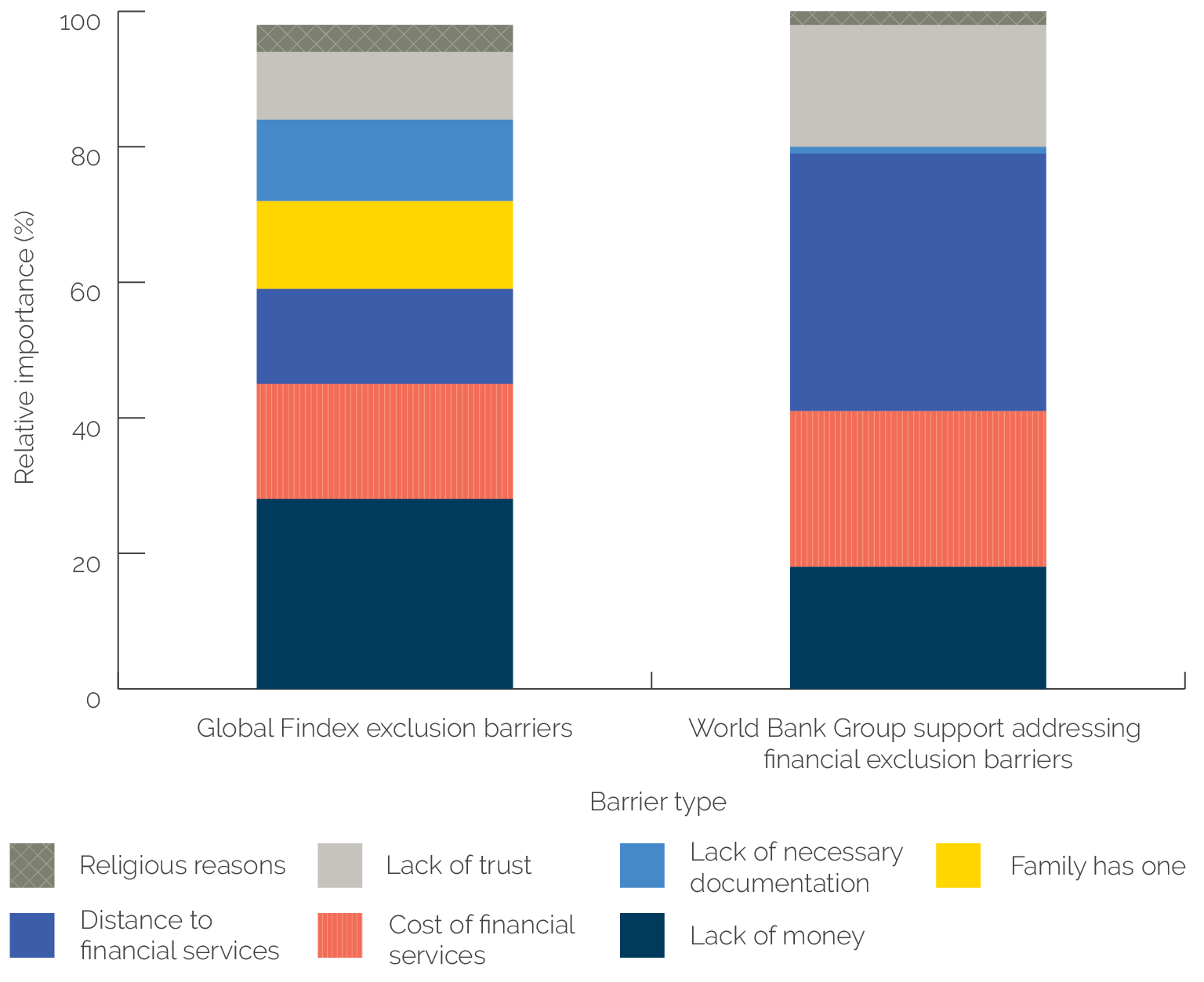

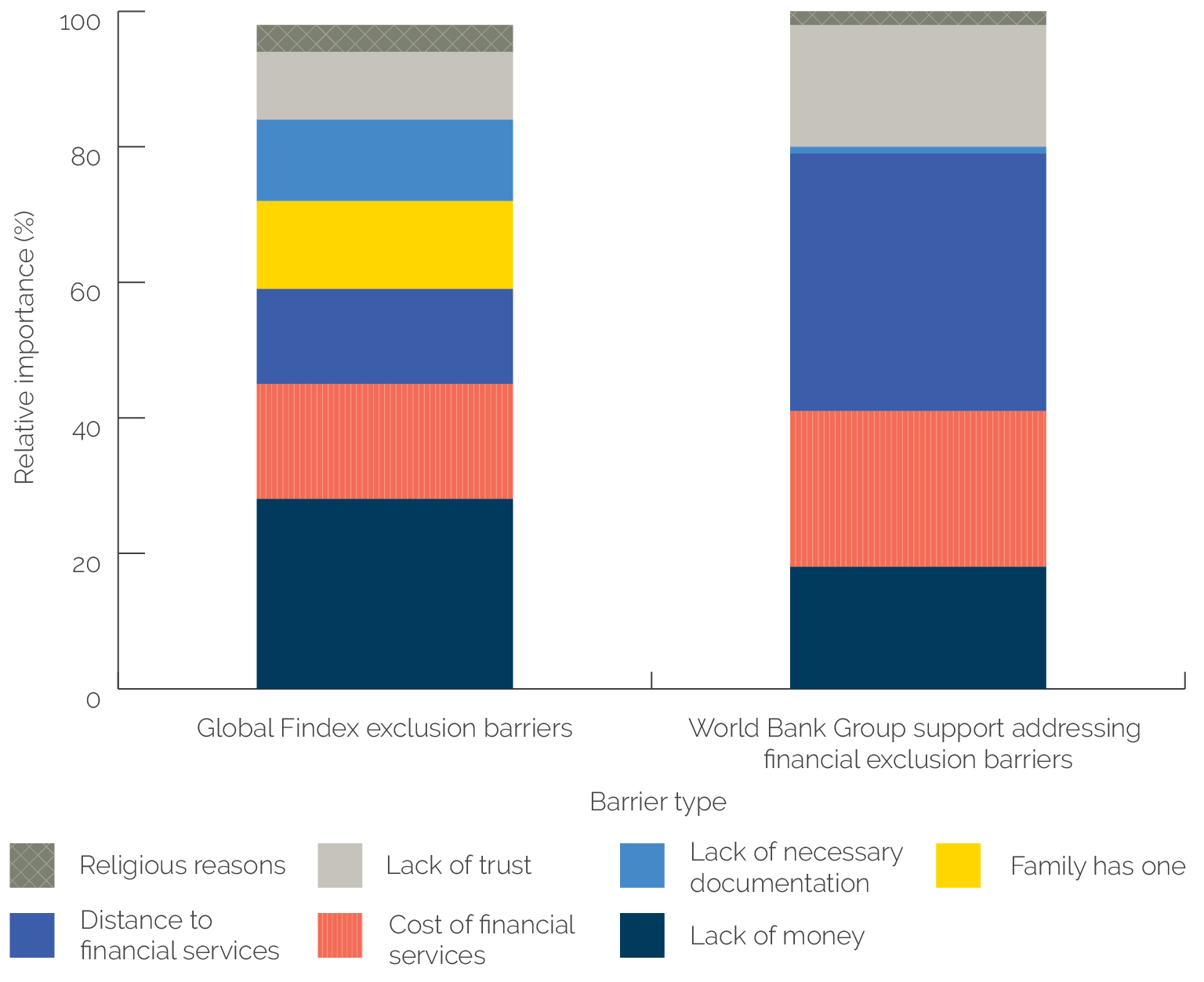

The Bank Group’s global portfolio is generally relevant to some important identified constraints of the financially excluded, especially cost of services and distance to financial services. To help shed light on why people do not have a financial account, the Global Findex 2021 survey asked unbanked adults to explain why they did not have an account. When mapping these barriers to the Bank Group portfolio (figure 2.5), it is clear that the portfolio is attempting to address most of these constraints but with differences in emphasis. The Bank Group placed a strong emphasis on addressing distance to financial services and price of services, which are two of the three top barriers to having a financial institution account. Substantial emphasis is placed on the cost of financial services, the distance to financial service providers, and the lack of trust in financial institutions. Less relative emphasis is evident on addressing lack of money, lack of documentation, or religious barriers. Given the scope of this evaluation, it is not possible to determine whether the Bank Group addressed lack of money in other ways, for example, through social transfers or employment creation. In addition, some areas of Bank Group global leadership, such as the ID4D initiative, may not be reflected in the financial inclusion portfolio.

Figure 2.5. World Bank Group Alignment with the Barriers Facing Financially Excluded People

Source: Independent Evaluation Group portfolio review and analysis.

Note: Global Findex exclusion reasons consider data reported in developing countries in 2021. Distribution is projected according to expansion factors calculated using a stratified random sample of World Bank advisory services and analytics and unevaluated projects. The sampling framework considered institution, instrument, Region, and country income level as strata.

Country Relevance

At the country level, Bank Group support for NFISs varied substantially, adapting to different levels of country client commitment, capability, and access to alternative sources of support. The World Bank took a leading role in supporting NFISs (box 2.1) in countries where client commitment was relatively strong and other donors were not taking the lead. In 4 out of 10 IEG case study countries, the World Bank helped define or formulate the NFIS and implement it. Mozambique and Pakistan exhibit strong alignment of Bank Group support with formulating and implementing the NFIS. Both had the support of the World Bank–administered Financial Inclusion Support Framework, a trust fund supporting the achievement of financial inclusion goals. In Mozambique, the World Bank supported the development of its 2015 NFIS covering the period 2016–22. With advisory support financed by the trust fund, the World Bank helped authorities in the Ministry of Finance and the central bank formulate and launch the NFIS. The World Bank supported Pakistan’s NFIS with diagnostic tools, technical notes, and policy advice (such as identification systems and G2P transfers) and led private sector consultations. These informed the NFIS (through reimbursable AS) and supported reforms in payments in G2P transfers, consumer protection, and financial literacy.

NFISs varied in their clarity, comprehensiveness, governance provisions, and explicitness of targets. Stronger NFISs established clear and comprehensive goals and explicit targets, based on sound analysis. They set out clear leadership responsibility and high-level priorities. A positive example was Indonesia’s 2016 NFIS, which established effective governance, a clear agenda, and ambitious goals. By contrast, weaker NFISs often lacked balanced goals for inclusion (beyond access), clear assignment of responsibilities, clear targets, or adequate monitoring. Several NFISs fell short in terms of setting explicit targets and implementation arrangements. Among IEG case study countries, NFISs from before 2018 were generally weaker than more recent ones. For example, several early NFISs did not prioritize gender or excluded groups, and some depended heavily on broad access targets without explicit aims for other dimensions of inclusion. Tanzania’s second NFIS improved on the first by identifying constraints for inclusion of women, youth, and MSMEs and set indicator-based targets. In between were NFISs that hit the mark in most but not all respects. Mozambique’s 2015 NFIS had an adequate analytic foundation and governance structure and clear priorities. However, its initial priority targets omitted gender despite a profound gender gap.

Box 2.1. National Financial Inclusion Strategies

A national financial inclusion strategy aims to provide a road map of actions at the national or subnational level that stakeholders agree to follow to achieve financial inclusion objectives. National financial inclusion strategies allocate responsibilities among stakeholders, plan for resource requirements, and establish priority targets. The World Bank Group considers a strong national financial inclusion strategy to include several elements.

Strategies are comprehensive, promoting the uptake and use of a broad range of financial services and building on a clear understanding of the foundations and drivers of financial inclusion.

Strategic targets are evidence based, concrete, measurable, and verifiable, reflecting clear priorities and sequencing, and informed by stakeholder consultation, including with the private sector.

Implementation is led through a well-defined governance structure with a clear mandate and dedicated resources.

Monitoring and evaluation should ensure that the implementation of the strategy is on track and that policies and activities can be adjusted in real time.

Sources: Independent Evaluation Group document review; interviews; World Bank 2015c.

In some countries, the Bank Group’s engagement on financial inclusion was lower, responding to a low level of government commitment to financial inclusion or a shift in priorities toward other goals. Nigeria delegated financial inclusion policy to the central bank, which prioritized financial stability over inclusion. In Tanzania, a change in government priorities reduced commitment to financial inclusion over time. Although committed to financial inclusion, Bangladesh adopted an NFIS late in the evaluation period; thus, the Bank Group supported financial inclusion without this framework.

Where the World Bank did not lead support in defining or formulating the NFIS, it supported aspects of its implementation. The World Bank did not lead the formulation of 6 out of 10 NFIS strategies where other global and regional donors took the leading role. Despite this, the Bank Group played a role in all 10 of the country cases. For example, in Colombia, the World Bank supported the NFIS by establishing critical milestones for financial inclusion strategy and policy framework strategies. It provided advisory support on strengthening consumer protection and financial literacy. In Tanzania, before government priorities changed, the World Bank supported reform of the financial inclusion regulatory framework, and IFC supported improving financial infrastructure, women’s access, and mobile financial services.

Where multiple donors are present, the Bank Group sometimes works through collaboration or a clear division of labor. We found that 14 percent of Bank Group projects involve explicit collaboration or complementarities with other donors. For example, in the Philippines, the World Bank financed analytical work from a Korean trust fund. It also drew support from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, an Australian government trust fund, and a Bank Group multidonor trust fund in support of the ID4D initiative aiming for digital transformation. In Mozambique, donors indicated that they had an accepted division of labor to avoid overlaps and enhance complementarity. Nonetheless, where multiple donors are present, there could be elements of competition and difficulties attributing outcomes.

Country case studies also show that Bank Group country strategies became increasingly aligned with national financial inclusion goals over the evaluation period. Earlier Bank Group country strategies focus on financial inclusion through services to MSMEs and general access to financial accounts. More recently, Bank Group country strategies show a more explicit focus on additional financial inclusion objectives, such as ease of use and affordability, and on targeting underserved groups.3 For example, the Nigeria Country Partnership Strategy for 2014–17 envisioned general support for access to financial services as part of Nigeria’s development agenda to help expand its nonoil growth but articulated few goals beyond access and did not target specific populations. The Country Partnership Framework for 2021–25 is explicitly aligned with NFIS goals, with gender empowerment as a core objective.

Echoing a global and corporate shift toward a greater focus on gender, several of the Bank Group’s country engagements increasingly (but not uniformly) addressed women’s financial inclusion over the period, especially since 2018. In the Philippines, although both country strategies noted that gender would be mainstreamed,4 the most recent Country Partnership Framework (for 2019–23) emphasized gender support, including empowerment of poor people and vulnerable groups and economic growth. The Tanzania Country Assistance Strategy for 2018–22 proposed to design tailored financial products for MSMEs and women. The Nigeria Country Partnership Framework for 2021–25 supports financial products tailored for women. However, the focus on women was not uniform, and a focus on other excluded groups was less common. Several strategies did not identify women, low-income communities, and vulnerable groups as target populations.

IFC’s support under its UFA2020 Country Action Plans was aligned with supporting traditional financial sector providers to offer new services and reach new clients. IFC’s Country Action Plans were developed for each of the 25 UFA2020 priority countries to assess market size, need, and opportunities for enhancing financial access. IFC determined that the fastest and most efficient means of increasing account access for the unbanked population would be to support engagements that (i) targeted larger markets with significant gaps in account access and (ii) involved partners with an established infrastructure that enabled significant outreach to underserved areas. Thus, in UFA2020 countries, IFC’s projects were almost entirely conducted through financial institutions and largely aimed at microenterprises.

IFC’s Country Action Plans focused on three channels for increasing access: (i) building sustainable financial service providers, (ii) supporting DFS, and (iii) focusing on reaching underserved groups (in this case, MSMEs, especially those led by women). However, in UFA2020 priority countries, the portfolio indicates relatively less emphasis on the second channel—DFS—over the evaluation period. Although 87 percent of projects supported the first pillar and 84 percent the third, only 13 percent supported increasing DFS. Within projects supporting the third channel, 53 percent supported reaching microenterprises, 45 percent supported reaching women, 34 percent supported reaching rural customers, and only 1 percent sought to support reaching youth, older people, or ethnic minorities. In terms of financing dollar volume, 8 percent was oriented toward microenterprises.

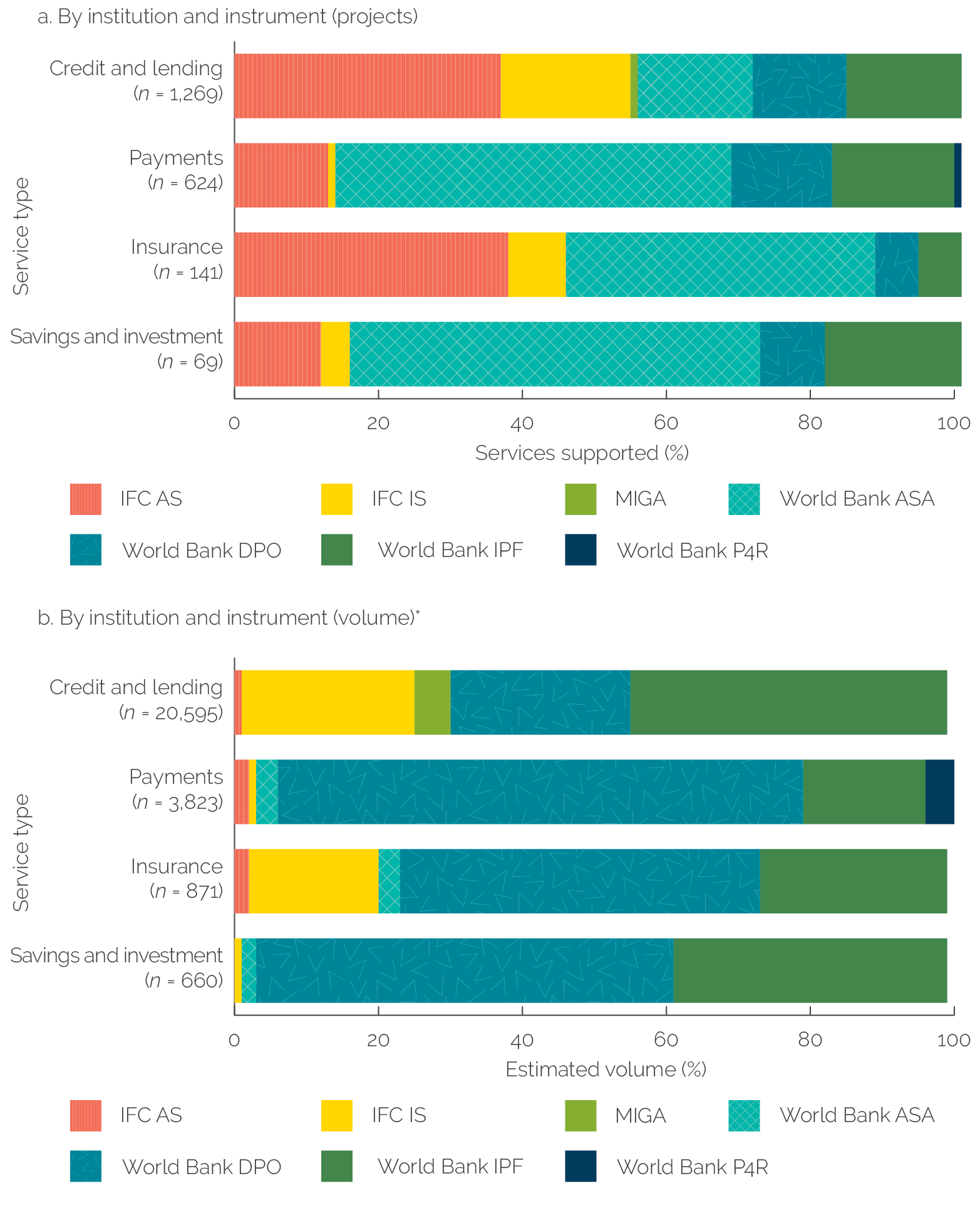

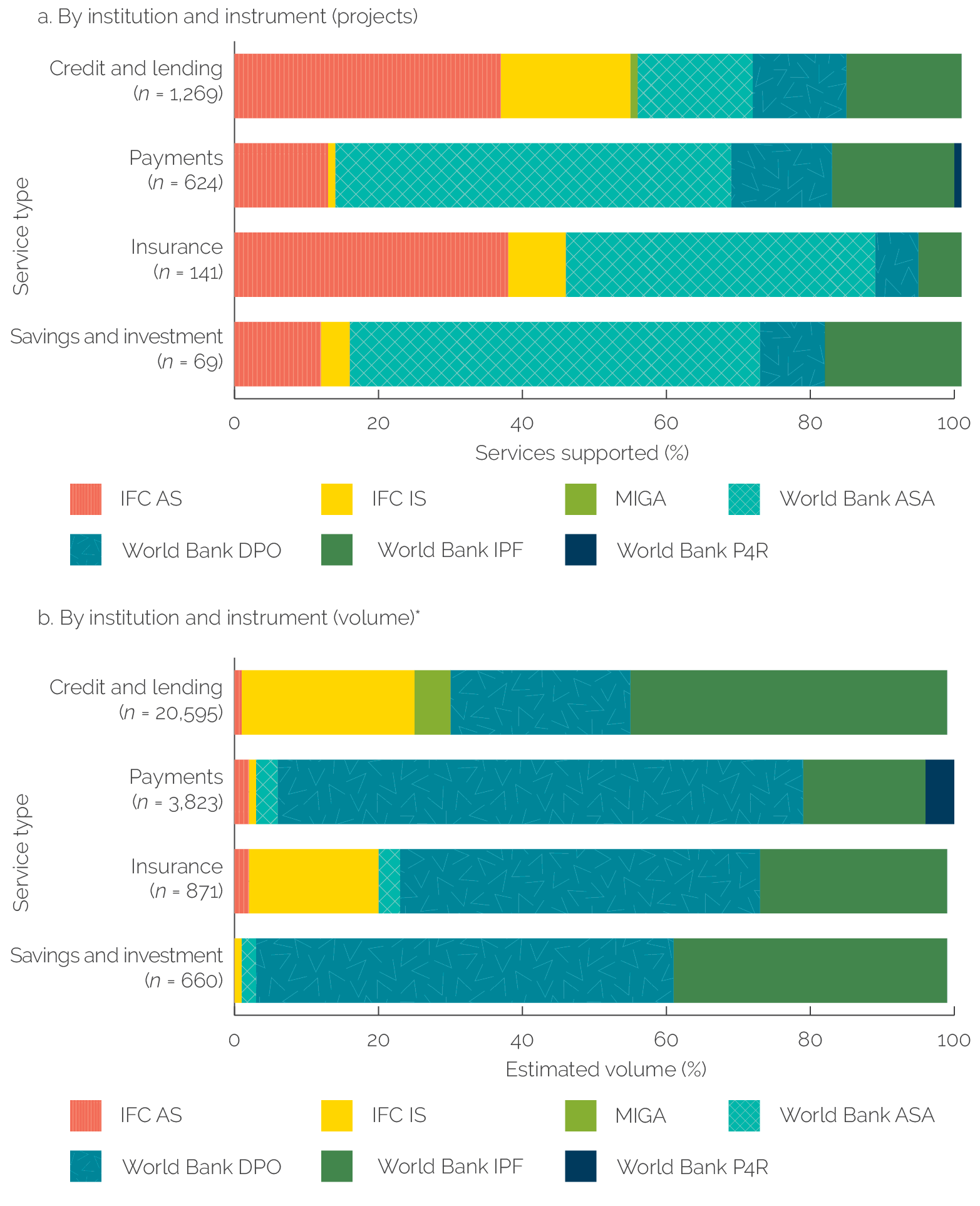

Instrument Relevance

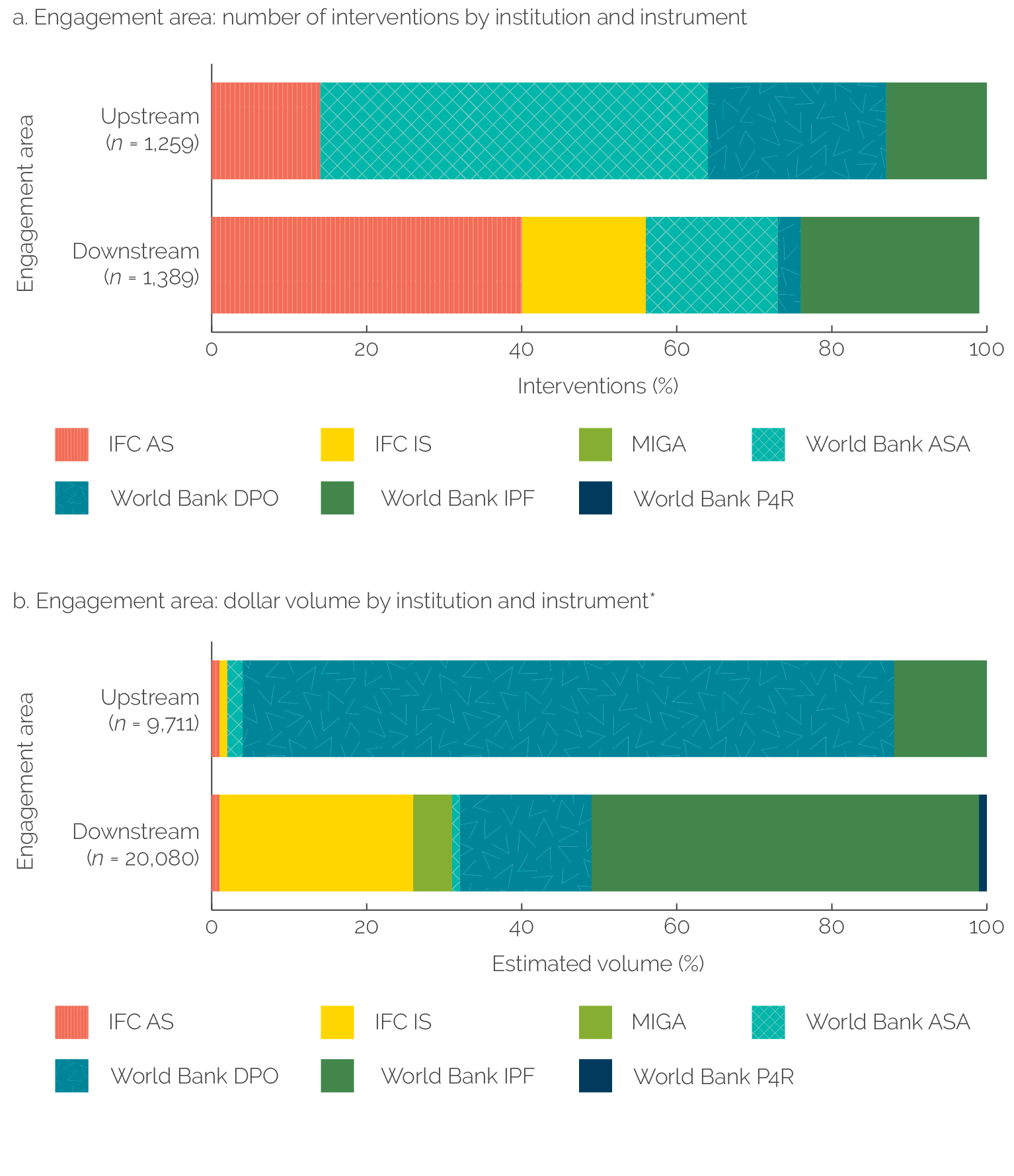

World Bank DPOs dominated the commitment value of the portfolio, whereas World Bank ASA and IFC AS were the most common by number of projects. Although it is impossible to attribute each instrument to a unique financial service, DPOs committed large amounts to support payments, insurance, and savings, whereas investment lending had the largest commitments to support credit (figure 2.6). IFC investments were strongly focused on credit; IFC used AS to support credit but also mobilized AS to support payments and insurance.

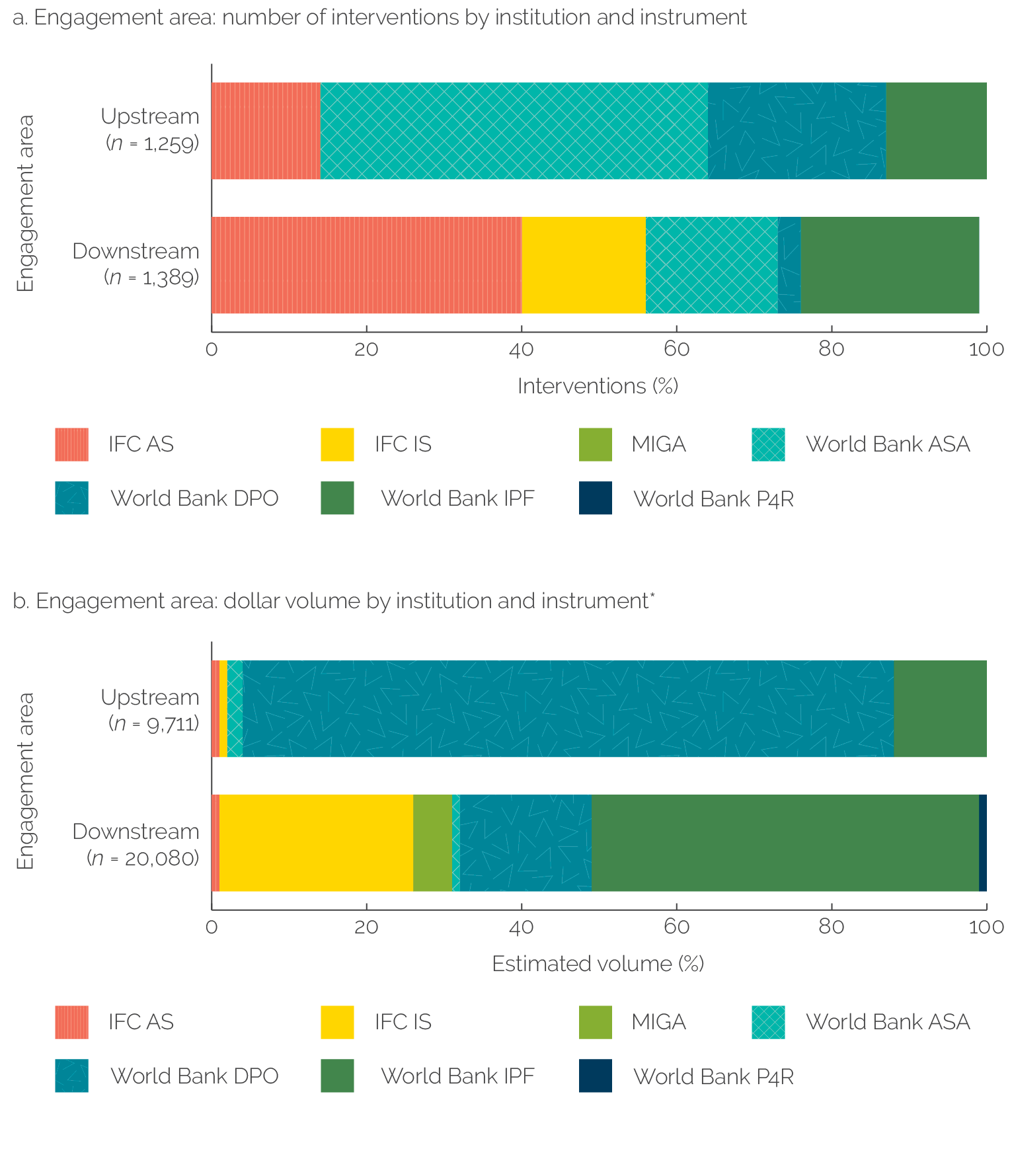

The alignment of instruments to objectives can be seen by separating projects supporting upstream (policy and institutional) reforms from those working downstream (for example, with service providers). When the World Bank seeks to influence policy, legal or regulatory reform, and reform of upstream institutions (such as regulators), it most often uses ASA and DPOs (figure 2.7). For example, in Ecuador, an ASA supported authorities in developing an NFIS. In South Sudan, an ASA helped the central bank establish oversight of the payment system.

To support upstream, IFC uses AS. In Bhutan, a large IFC AS project supported strengthening the national credit reporting framework by integrating data from utility companies. By dollar volume, DPOs are dominant in upstream engagements. For example, in Indonesia, a DPL strengthened financial system regulation by establishing a powerful independent institution responsible for regulation and supervision of all financial services and strengthening a regulatory framework for deposit insurance. IFC uses both AS and investments to support downstream service providers. In Brazil, an AS supported an insurance company in developing a product for low-income families. In China, an IFC investment project supported the establishment of a microcredit company. The World Bank mostly uses investment lending and ASA to engage downstream. In Sri Lanka, an investment project supported a warehouse receipt financing program that directly trained and built knowledge and capacity among stakeholders. In Zimbabwe, a World Bank ASA trained SMEs and microentrepreneurs in skills needed to apply for financing.

Figure 2.6. Services Supported by World Bank Group Instruments

Source: Independent Evaluation Group portfolio review and analysis.

Note: Figures are based on estimated volume in US$, millions. Distribution is projected according to expansion factors calculated using a stratified random sample of World Bank ASA and unevaluated projects. The sampling framework considered institution, instrument, Region, and country income level as strata. AS = advisory services; ASA = advisory services and analytics; DPO = development policy operation; IFC = International Finance Corporation; IPF = investment project financing; IS = investment services; MIGA = Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency; P4R = Program-for-Results. * To estimate total volume related to financial inclusion in DPOs and other multicomponent projects, the projects’ committed dollar value amount reported in project documentation was allocated proportionally among components (for example, prior actions for DPOs). Only components related to financial inclusion were considered. Where a component had multiple subcomponents, the committed amount was allocated proportionally to those subcomponents addressing financial inclusion.

Figure 2.7. Engagement Areas Supported by World Bank Group Instruments and Dollar Volume

Source: Independent Evaluation Group portfolio review and analysis.

Note: Figures are based on estimated volume in US$, millions. Distribution is projected according to expansion factors calculated using a stratified random sample of World Bank ASA and unevaluated projects. The sampling framework considered institution, instrument, Region, and country income level as strata. AS = advisory services; ASA = advisory services and analytics; DPO = development policy operation; IFC = International Finance Corporation; IPF = investment project financing; IS = investment services; MIGA = Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency; P4R = Program-for-Results. * To estimate total volume related to financial inclusion in DPOs and other multicomponent projects, the projects’ committed dollar value amount reported in project documentation was allocated proportionally among components (for example, prior actions for DPOs). Only components related to financial inclusion were considered. Where a component had multiple subcomponents, the committed amount was allocated proportionally to those subcomponents addressing financial inclusion.

World Bank ASA for payment services accounted for about one-third of the ASA projects. ASA delivered most support in the form of reports, diagnostic reviews, and training or workshops but also produced strategies, policy notes, and FSAPs (box 2.2). Diagnostic reviews covered multiple topics, such as the housing finance market in Vietnam and Iraq, financial education in Peru and China, competition in the payment system in Peru, consumer protection in the Dominican Republic, and DFS in Colombia, Burkina Faso, and Senegal.

Box 2.2. Influence of Financial Sector Assessment Programs on Country Financial Inclusion Strategies

Financial Sector Assessment Programs (FSAPs) have played a relevant role in supporting the formulation and implementation of financial inclusion work. Over the years, FSAPs have maintained core financial sector coverage through their technical notes, but coverage has evolved to include financial inclusion challenges. The World Bank has taken the lead in preparing technical notes on financial inclusion as part of its participation in joint International Monetary Fund–World Bank FSAPs. Between 2016 and 2022, the World Bank produced 46 technical notes on financial inclusion. Among them, the top three topics were digital financial services and payment systems, financial inclusion strategies, and financial infrastructure. Much attention is focused on finance for micro, small, and medium enterprises, with very limited attention given to women or other underserved groups.

The Independent Evaluation Group’s country case studies show that the FSAP is accepted by key stakeholders as an important tool to identify challenges and raise awareness of policy makers on financial inclusion. For example, in Colombia, the FSAP was key to addressing specific aspects of national financial inclusion strategy implementation, such as reforming governance arrangements; coordinating among key agencies in charge of regulating, supervising, and overseeing payment systems and instruments; and finding effective ways to share consumer data to underpin new financial products. In Morocco, to stimulate micro, small, and medium enterprise finance, the FSAP recommended a shift from cofinancing and guarantees to the development of enabling technologies and joint platforms, such as mobile banking. It also called for better identification of underserviced segments of the population to better target and monitor financial access programs. Moroccan authorities subsequently committed to enhanced data collection initiatives and have diversified financial product offerings.

Source: Independent Evaluation Group review of Financial Sector Assessment Programs and case studies.

- This pertains specifically to pillar 2A—fast-track credit enhancement to financial institutions for working capital financing to micro, small, and medium enterprises; corporates; and individuals.

- Development policy operations can extend development policy financing as loans (development policy loans), credits (development policy credits), or grants (development policy grants).

- Through 2014, World Bank Group country strategies were known as Country Assistance Strategies or Country Partnership Strategies. In 2014, the Country Partnership Framework replaced the Country Assistance Strategy and Country Partnership Strategy.

- Gender mainstreaming is defined in the Philippines Country Gender Action Plan and includes the equal representation of women and men in the design and implementation of key activities, availability of sex-disaggregated data, and presence of gender focal persons in the project team. Going forward, the World Bank will implement the recommendation that projects enhance their initiatives for more in-depth analysis of sex-disaggregated data and strengthen the link with the broader gender policy of the government implementing agency.