An Evaluation of World Bank and International Finance Corporation Engagement for Gender Equality over the Past 10 Years

Chapter 2 | Engagement for Gender Equality

Highlights

Beginning in 2012 and especially after the adoption of the fiscal year 2016–23 gender strategy, the share of World Bank and International Finance Corporation (IFC) gender-relevant projects increased in all Practice Groups and industries.

However, the expansion of gender-relevant projects involved breadth more than depth—the share of World Bank and IFC investment projects with low gender relevance increased much more compared with those with high gender relevance, and the projects including robust and gender-transformative theories of change only slightly increased. Against the trend in World Bank and IFC investments, IFC advisory work selectively focused its engagement on a subgroup of substantially gender-relevant projects.

The World Bank’s increasingly ambitious gender tag targets coincided with the tag becoming less stringent. Specifically, the increase of targets of gender tag incentivized an increase of the minimum quality standard, but gender-transformative projects with robust theories of change were not sufficiently incentivized. Moreover, the gender tag incentivized design more than implementation.

IFC is increasing gender flag targets for advisory services and investments, which risks losing a more selective approach to addressing gender inequalities and could dilute IFC efforts if the level of ambition is not matched by additional resources.

Despite country strategies identifying gender priorities that align with needs, the country-driven approach is not strategic enough and is fragmented, with various instruments, sectors, and institutions weakly coordinated.

The World Bank and IFC are increasingly producing robust gender diagnostics to support the identification of gender priorities in Country Partnership Frameworks, inform the integration of policy actions in development policy operations, and feed into policy dialogue on gender equality. The World Bank and IFC are also increasingly piloting and evaluating activities that can reduce gender inequalities. However, they still struggle to operationalize lessons on “what works” to achieve results.

This chapter discusses the evolution of the Bank Group engagement for gender equality between FY12 and FY23, the implementation of the country-driven approach,1 and the role of knowledge in supporting these developments. The chapter discusses how the World Bank gender tag and IFC gender flag influenced the evolution of the gender engagement, the role of the FY16–23 gender strategy, and the impact of enabling and constraining factors, including the availability and management of human and financial resources and the incentives for internal and external collaboration.

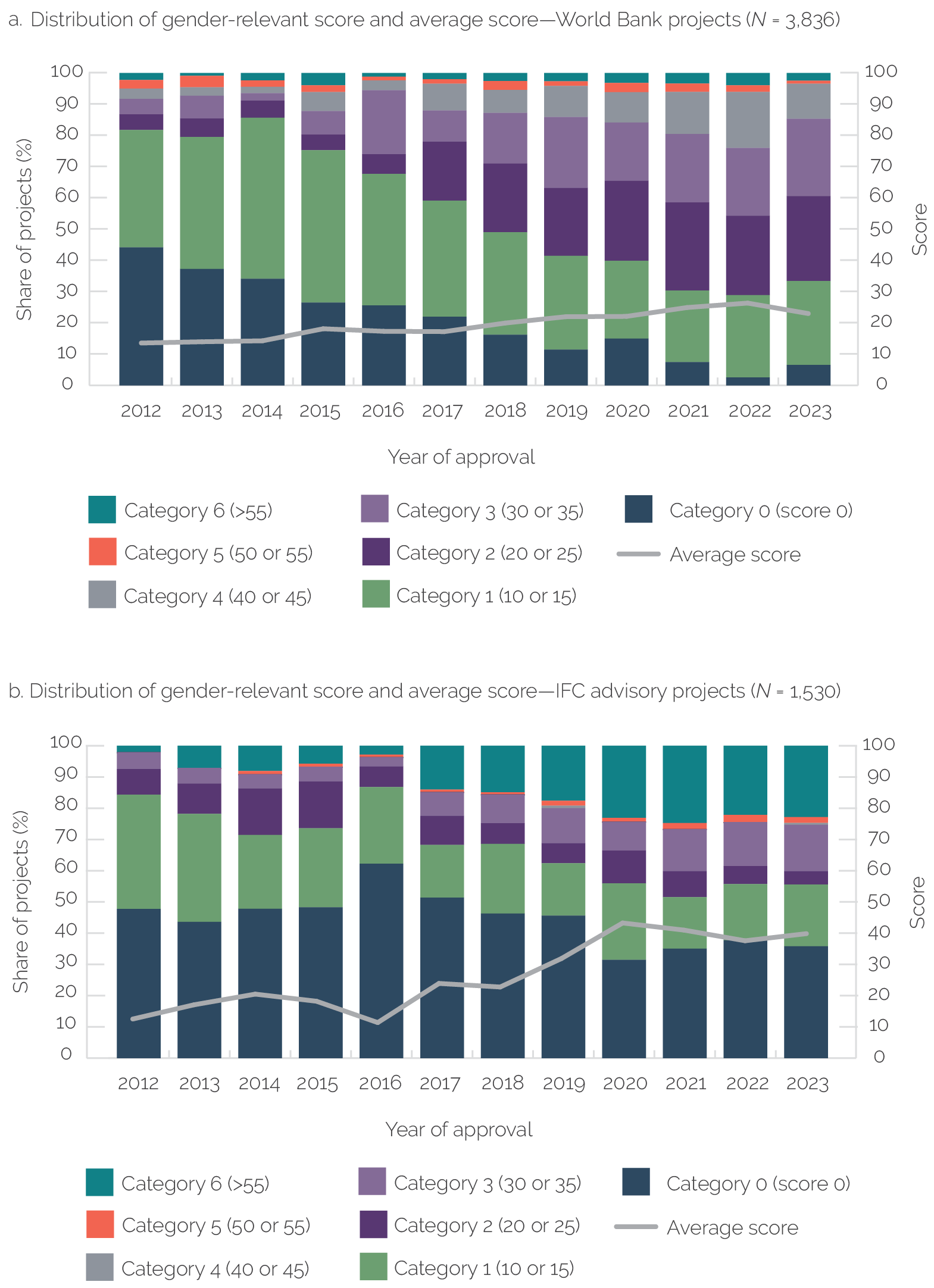

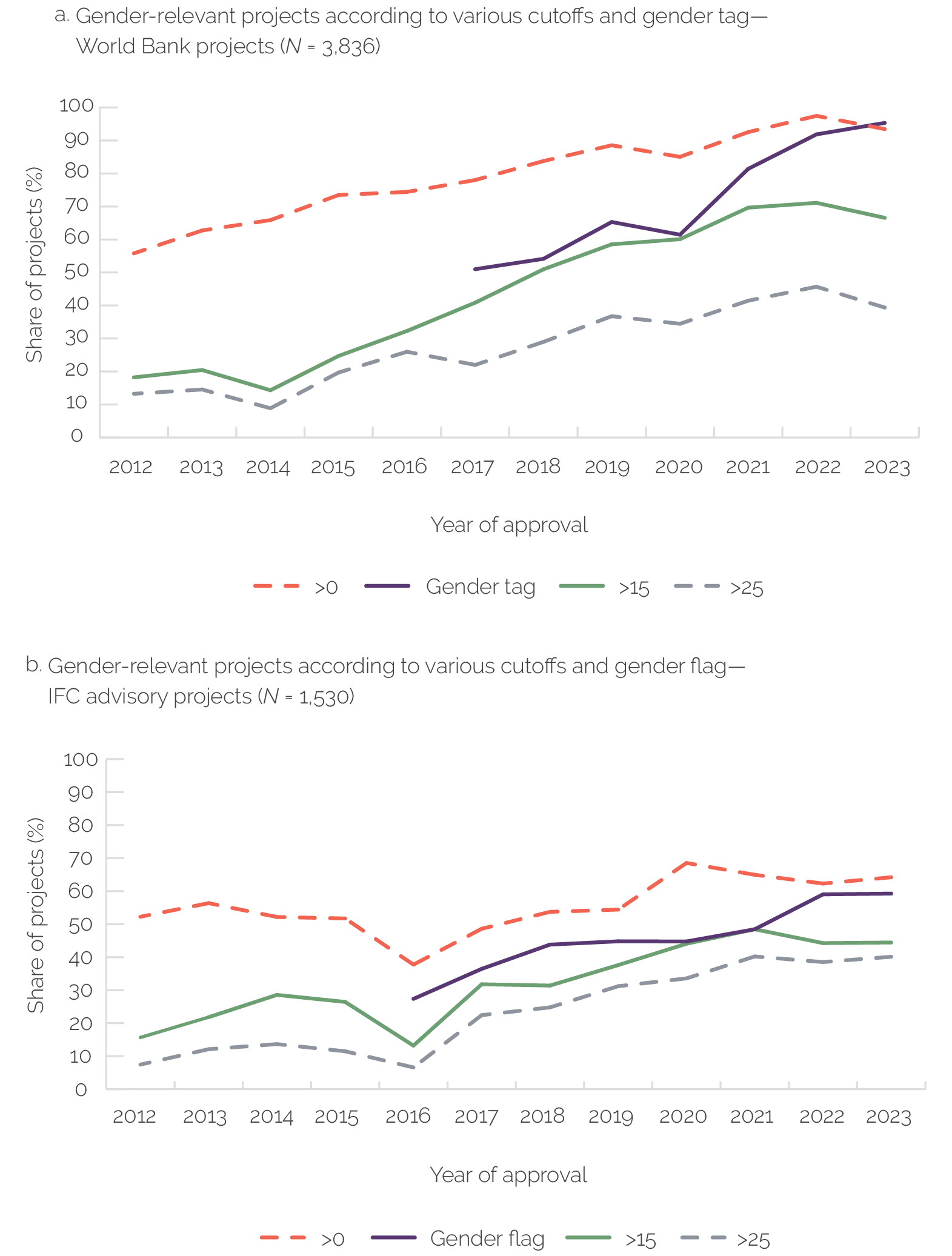

Evolution of the World Bank Group Engagement for Gender Equality

Over the evaluation period, the engagement for gender equality increased, as demonstrated by the increase of the share of World Bank and IFC projects deemed gender relevant. This evaluation uses an algorithm that combines several project characteristics to create an index of gender relevance intensity (box 2.1 and appendix E) and to assess how the share of gender-relevant projects changed over time.2 Between FY12 and FY23, the World Bank and IFC lending portfolios became more gender relevant. The share of World Bank projects with the lowest scores (in the 0–15 range) decreased throughout the evaluation period, whereas the share of projects with a 20+ score progressively increased. In IFC, the trend was similar, with the share of projects with the lowest scores decreasing for both IFC investments and IFC advisory projects (figure 2.1). The average score also increased, although modestly for IFC investments.

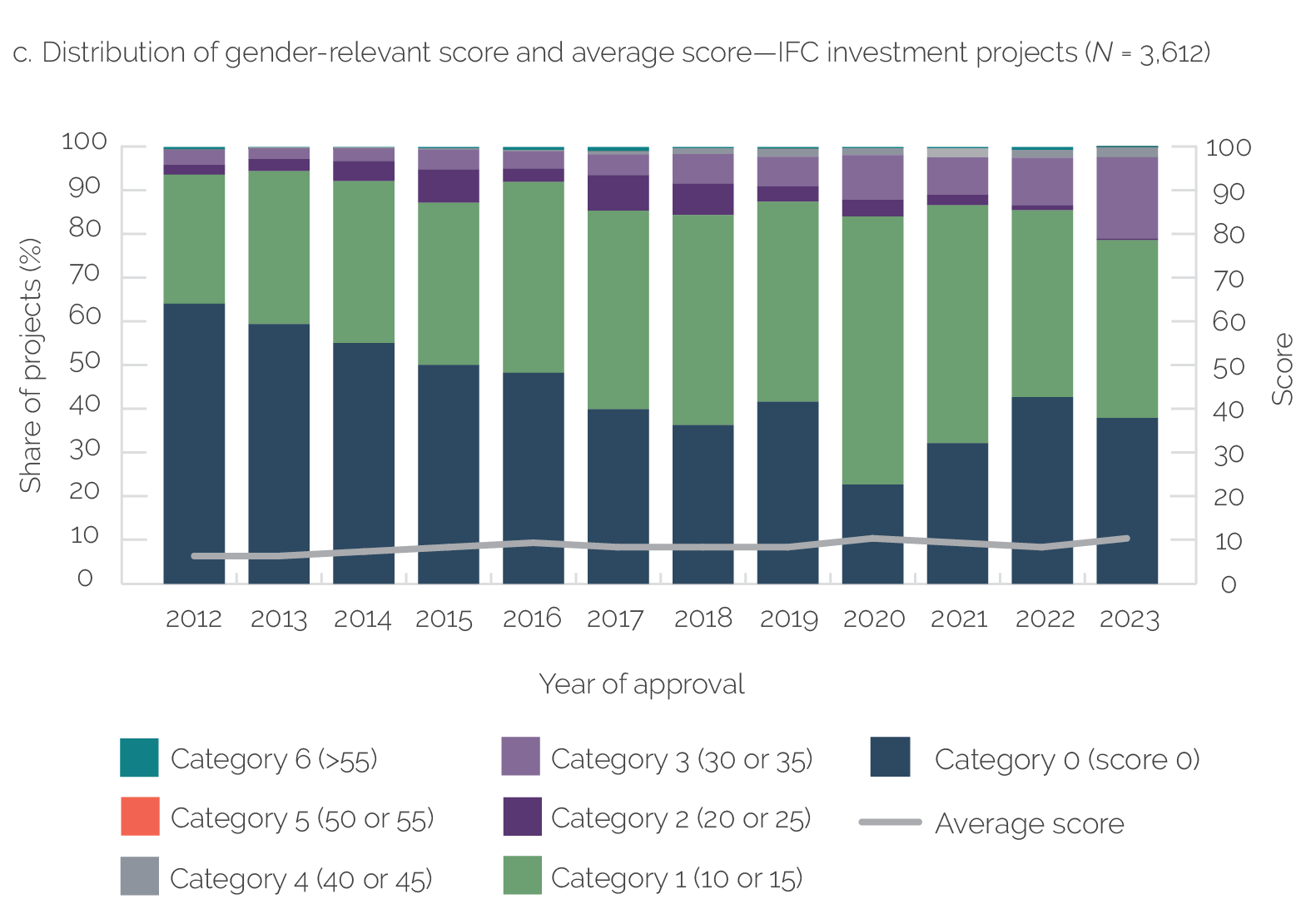

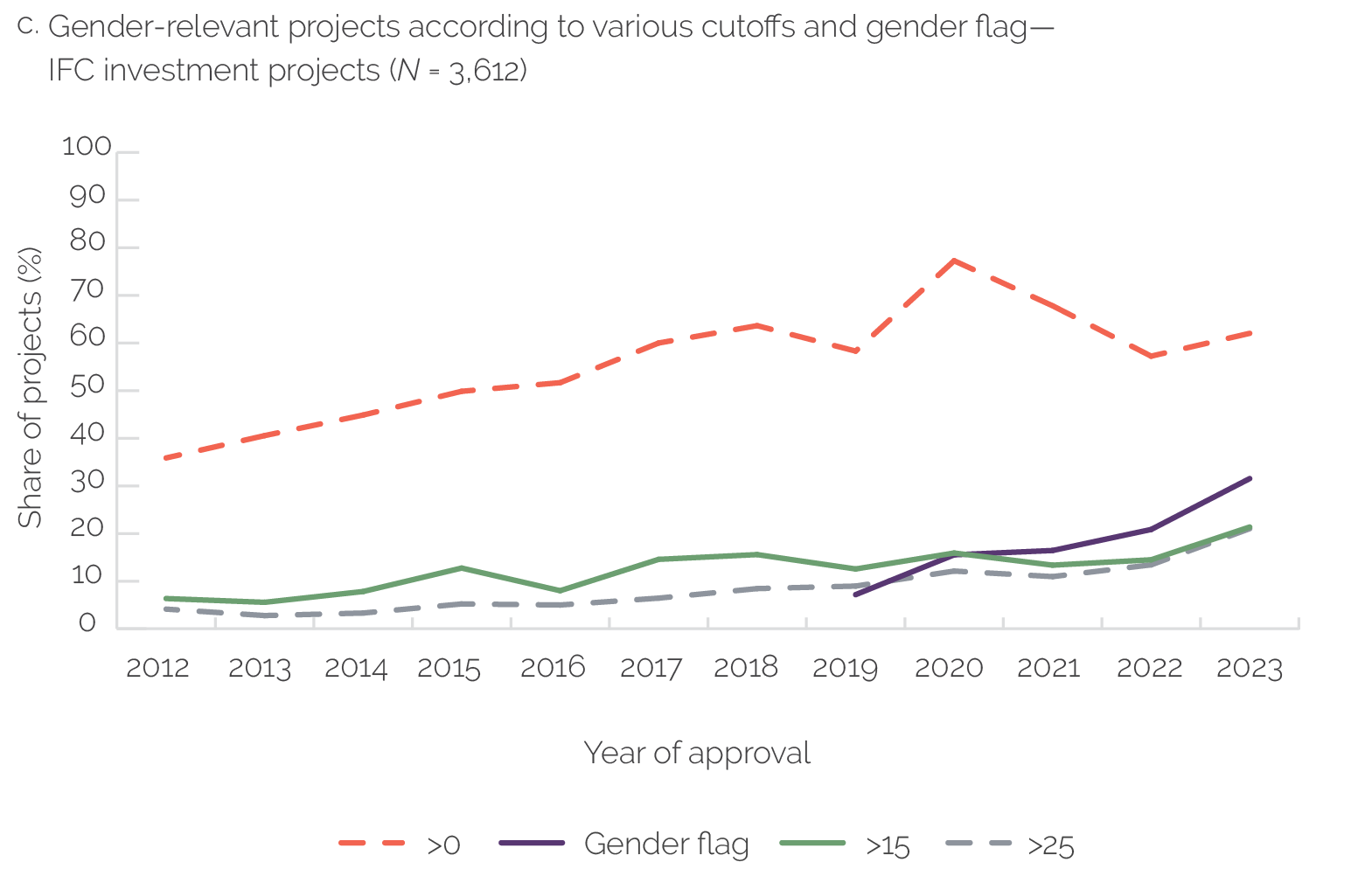

The share of gender-relevant projects increased irrespective of how stringent the definition of gender relevance is. Alternative score cutoff values—corresponding to more or less generous standards of gender relevance—all suggest an increase of the share of gender-relevant projects throughout the evaluation period (figure 2.2). For IFC advisory projects, the increase started after the approval of the FY16–23 gender strategy, whereas for the World Bank, the share of gender-relevant projects was already following an upward trend. This represents important progress. Increasing the number of gender-relevant projects is a necessary, albeit not sufficient, condition for Bank Group contributions to reducing gender inequality.

Box 2.1. Defining the Gender Relevance of Projects

Many donors have developed criteria for operational teams to assess how well their policies and programs contribute to gender equality. Besides establishing safeguards to ensure that projects do not cause unintended harm (in the form of gender-based violence, sexual exploitation, and harassment), many organizations also require projects to contribute to addressing gender inequalities, either directly or indirectly, based on their gender policies. Checklists, scores, and targets provide guidelines and incentives to staff and are used for quality assurance, monitoring, accountability, and reporting purposes.

The United Nations gender equality marker (GEM), for example, uses a coding scale from 0 to 3 (UNSDG 2024) to distinguish whether an activity is not expected to contribute to gender equality (GEM 0), contributes to gender equality and the empowerment of women in a limited way (GEM 1), has gender equality and the empowerment of women as a significant objective (GEM 2), or has gender equality and the empowerment of women as the principal objective (GEM 3). The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s Development Assistance Committee gender equality policy marker is based on a three-point scoring system (OECD 2016) distinguishing whether gender equality is part of the project objective: not targeted (0), significant (1), and principal (2).

The World Bank Group gender tag and flag mark projects that, at design, clearly articulate how they will contribute toward narrowing specified gender gaps. The flag and tag are expressed as a binary variable, where a 1 is assigned if the project includes an analysis to identify gender gaps relevant to the project objectives, actions to address those gaps, and indicators measuring progress on the proposed actions (IFC 2023; World Bank 2022a).

The implementation of each scoring system requires a judgment by operational teams and validators of “how much is enough” to decide whether a project “identifies,” “contributes to,” or “addresses” gender gaps. This implicit standard of gender relevance is even harder to gauge for a less granular system, such as the Bank Group one.

This evaluation developed an algorithm to measure different intensities of gender relevance. The algorithm, after being calibrated using a sample of manually reviewed projects, is used to calculate a score by taking discrete values between 0 and 100 that can be considered a good proxy of how gender relevant each project is. The algorithm combines 9 attributes for World Bank projects, 10 attributes for International Finance Corporation (IFC) advisory projects, and 8 attributes for IFC investment projects. These attributes include variables constructed using text analysis of project documents and other project characteristics (see appendix E). Robustness tests were conducted by manually identifying stand-alone projects (based on the project title and project development objective) and comparing this identification with the one generated by the score (for 122 World Bank, 69 IFC advisory, and 14 IFC investment stand-alone projects). We found that the algorithm identified stand-alone projects quite precisely. A strong correlation was also found between the score assigned by the gender algorithm and the manually determined gender relevance of 154 IFC advisory projects, 201 IFC investment projects, and country case study projects.

The evaluation uses the score to define various cutoff values and to show how the share of gender-relevant project changes, based on more or less generous definitions of gender relevance to World Bank and IFC projects. It normally uses a greater than 15 cutoff value for analyses that require a specific definition of gender relevance.

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Figure 2.1. Distribution of the Gender-Relevant Score, Fiscal Years 2012–23

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: For the World Bank, the entire population of International Bank for Reconstruction and Development and International Development Association projects (investment project financing, Programs-for-Results, and development policy operations) is included. Additional financing is counted separately, but additional financing of parent projects approved before 2012 is excluded. For IFC, all investments committed from fiscal year 2012 to fiscal year 2023 and all advisory services approved from fiscal year 2012 to fiscal year 2023 are included. Category 0 includes projects whose score is 0, category 1 includes projects whose score is 10 or 15, category 2 includes projects whose score is 20 or 25, category 3 includes projects whose score is 30 or 35, category 4 includes projects whose score is 40 or 45, category 5 includes projects whose score is 50 or 55, and category 6 includes projects whose score is higher than 55 (up to 100). IFC = International Finance Corporation.

Figure 2.2. Share of Gender-Relevant Projects Based on Alternative Index Cutoff Values and the Gender Tag and the Gender Flag

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: For the World Bank, the entire population of International Bank for Reconstruction and Development and International Development Association projects (investment project financing, Programs-for-Results, and development policy operations) is included. Additional financing is counted separately, but additional financing of parent projects approved before 2012 is excluded. For IFC, all investments committed from fiscal year 2012 to fiscal year 2023 and all advisory services approved from fiscal year 2012 to fiscal year 2023 are included. World Bank gender tag data were accessed and compiled in May 2024. IFC gender flag data were accessed and compiled in December 2023. IFC = International Finance Corporation.

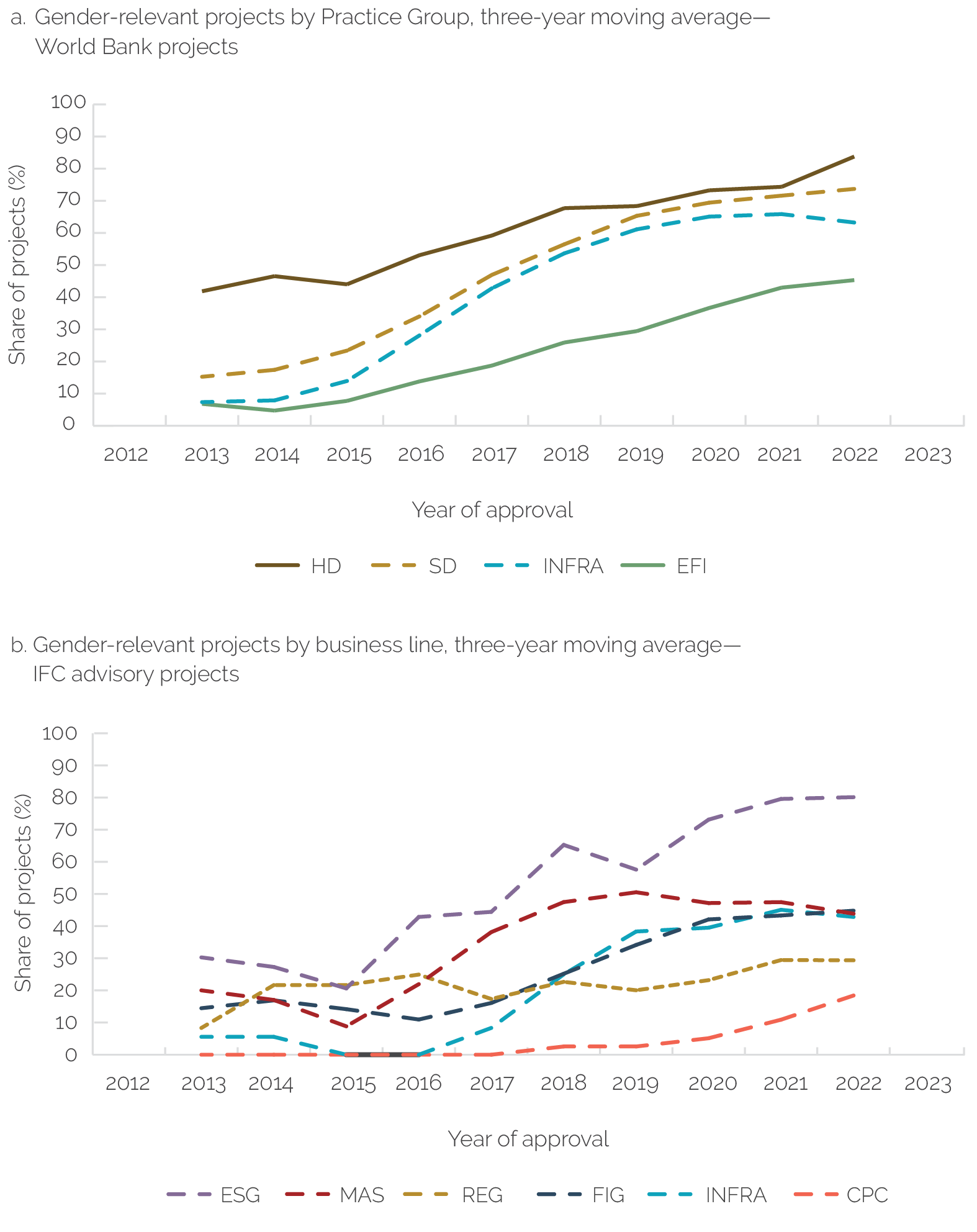

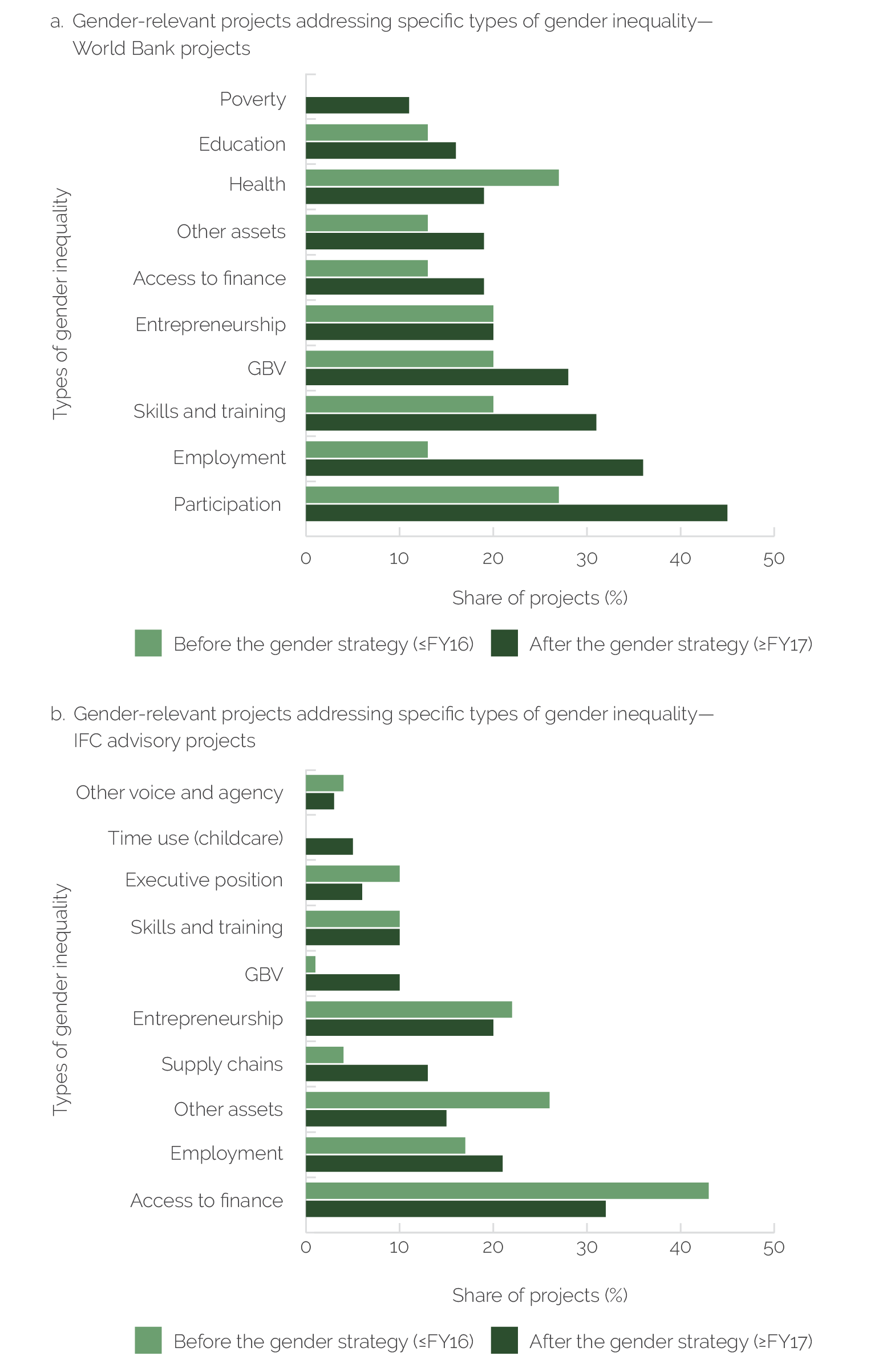

The share of gender-relevant projects increased in all Practice Groups and industries; some Practice Groups and industries had gender-relevant projects for the first time after the adoption of the FY16–23 gender strategy. Before FY16, Human Development was the only Practice Group with a large share of gender-relevant projects (figure 2.3, panel a), mostly in health and education. All other Practice Groups started from much lower levels—especially Infrastructure and Equitable Growth, Finance, and Institutions—but experienced a substantial increase starting from FY16. In the Equitable Growth, Finance, and Institutions Practice Group, part of the increase of gender-relevant projects was due to the increase of development policy operations (DPOs) with gender-relevant actions (as discussed in this chapter). For IFC, before the adoption of the strategy, most gender-relevant projects addressed gender gaps in access to finance; after the strategy, there was a notable expansion in Manufacturing, Agribusiness, and Services; Infrastructure for advisory projects; and Disruptive Technologies and Funds for investments, although financial access remained the predominant area.

This expansion and entry into new sectors of engagement are confirmed by the manual review of all eight country case study portfolios. The most remarkable improvement among the case studies happened in Tanzania, with the proportion of World Bank gender-relevant lending projects increasing from 23 percent to 70 percent. Furthermore, before the adoption of the strategy, gender-relevant projects were mostly concentrated in Human Development; however, after the strategy, they expanded into other Practice Groups, such as Sustainable Development (seven out of eight operations compared with one out of four in the early period) and Infrastructure (three out of seven operations compared with zero out of four in the early period).

Figure 2.3. Share of Gender-Relevant Projects, Practice Groups, and Industries

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: For the World Bank, the entire population of International Bank for Reconstruction and Development and International Development Association projects (investment project financing, Programs-for-Results, and development policy operations) is included. Additional financing is counted separately, but additional financing of parent projects approved before 2012 is excluded. For IFC, all investments committed from fiscal year 2012 to fiscal year 2023 and all advisory services approved from fiscal year 2012 to fiscal year 2023 are included. For both the World Bank and IFC, the gender intensity cutoff of greater than 15 is used to define gender relevance. For IFC, a business line is excluded if less than 5 percent of the gender-relevant portfolio belongs to that business line. CDF = Disruptive Technologies and Funds; CPC = Corporate Portfolio Committee; EFI = Equitable Growth, Finance, and Institutions; ESG = Environmental, Social, and Governance; FIG = Financial Institutions Group; FM = Financial Markets; HD = Human Development; IFC = International Finance Corporation; INFRA = Infrastructure; MAS = Manufacturing, Agribusiness, and Services; REG = Regional Advisory; SD = Sustainable Development.

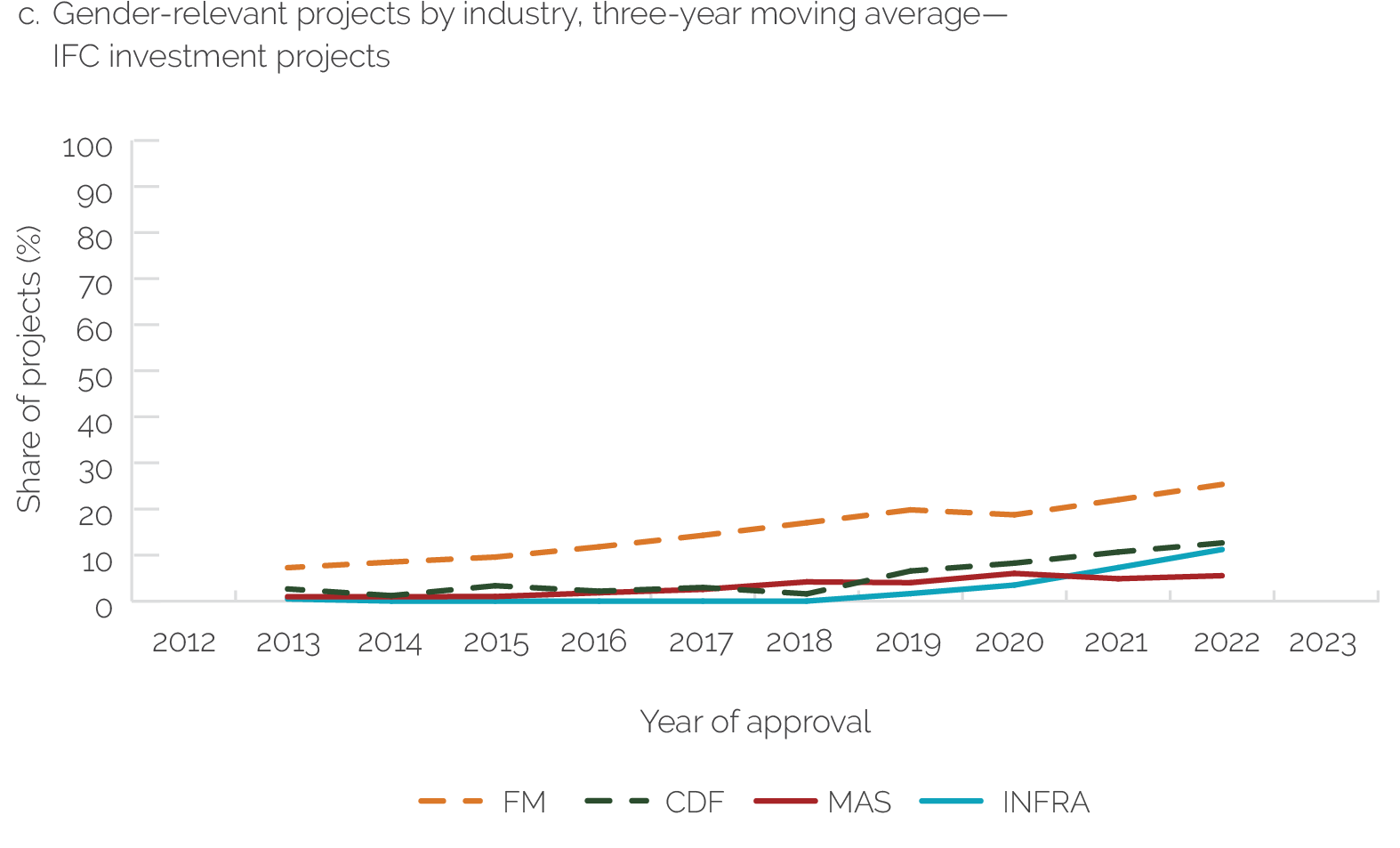

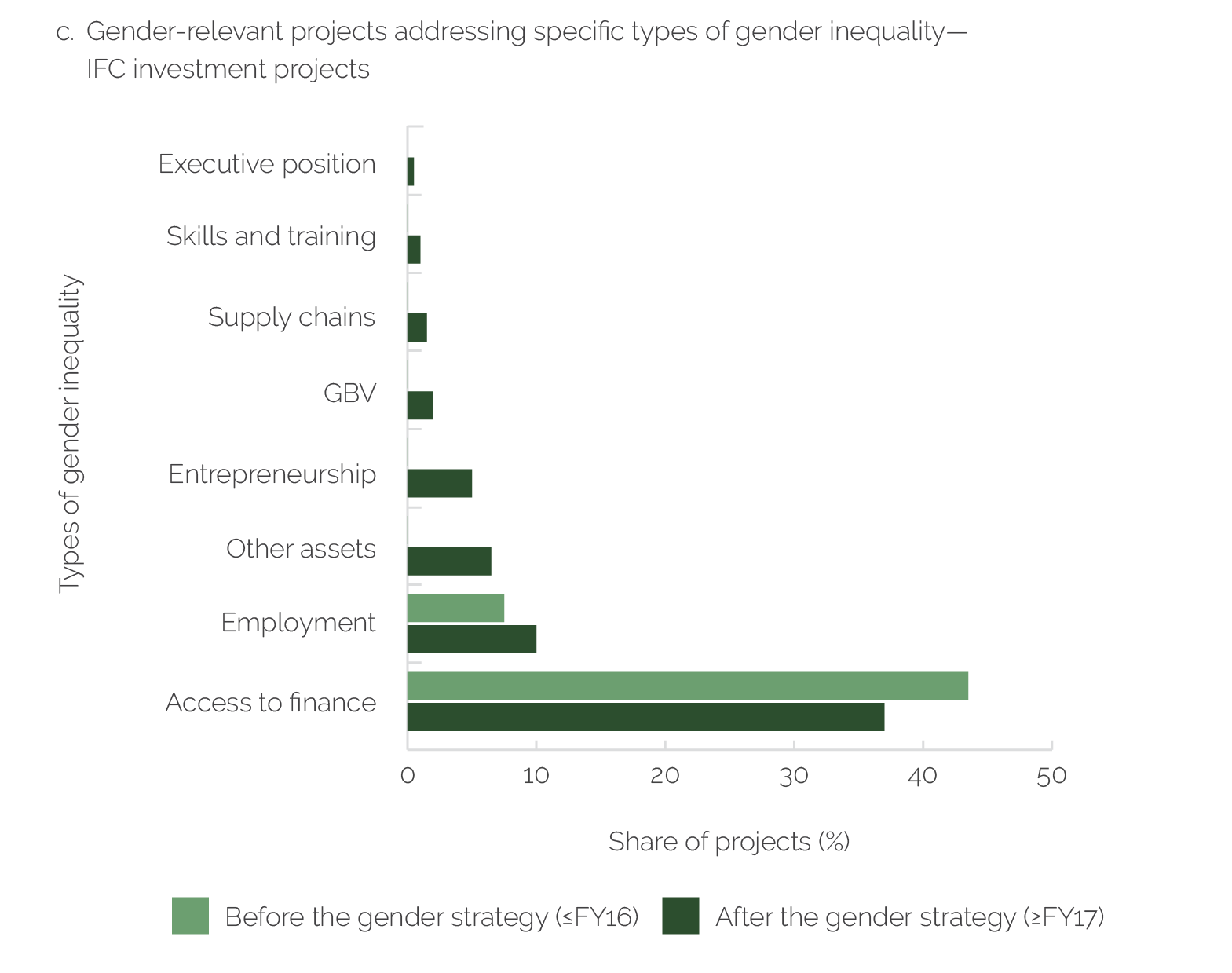

The increase of gender-relevant projects was accompanied by new types of gender inequalities being addressed, especially in IFC. In the absence of a Bank Group taxonomy of gender inequalities, this evaluation developed one using a mixed inductive-deductive approach (see appendix G), which was applied consistently throughout all evaluation tools. After the FY16–23 gender strategy, changes occurred in the types of gender inequalities addressed. In the World Bank, the percentage of projects addressing a specific type of gender inequality increased for almost every type of gender inequality except those related to health; this indicates an increase in projects addressing multiple gender inequalities at once—hence, an increase in the complexity of theories of change. For example, more projects included actions to strengthen women’s voice and agency while also addressing other gender gaps. In particular, projects addressing gender inequalities related to skills and training, GBV, employment (including time use and women’s double burden),3 and participation and decision-making substantially increased (figure 2.4, panel a). In IFC, projects began to address new types of gender inequalities that had never before been explicitly considered. In IFC advisory projects, these new types included GBV, time use (with more operations promoting employer-provided childcare), and supply chains (figure 2.4, panel b). In IFC investments, the bulk of projects continued to be represented by access to finance, but new projects addressed access to assets, entrepreneurship, supply chains, and GBV-related issues (figure 2.4, panel c). Moreover, in both IFC advisory and investment projects, the set of gender inequalities addressed became more diversified.

Figure 2.4. Types of Gender Inequality Addressed by Projects before and after the Fiscal Year 2016–23 Gender Strategy

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: For the World Bank, the gender gaps are calculated for a random sample of 200 parent projects approved from FY12 to FY23 of which 89 are gender-relevant projects using a cutoff greater than 15. For IFC, all gender-relevant (cutoff greater than 15) investments committed from FY12 to FY23 and all gender-relevant advisory services (cutoff greater than 15) approved from FY12 to FY23 are included. FY = fiscal year; GBV = gender-based violence; IFC = International Finance Corporation.

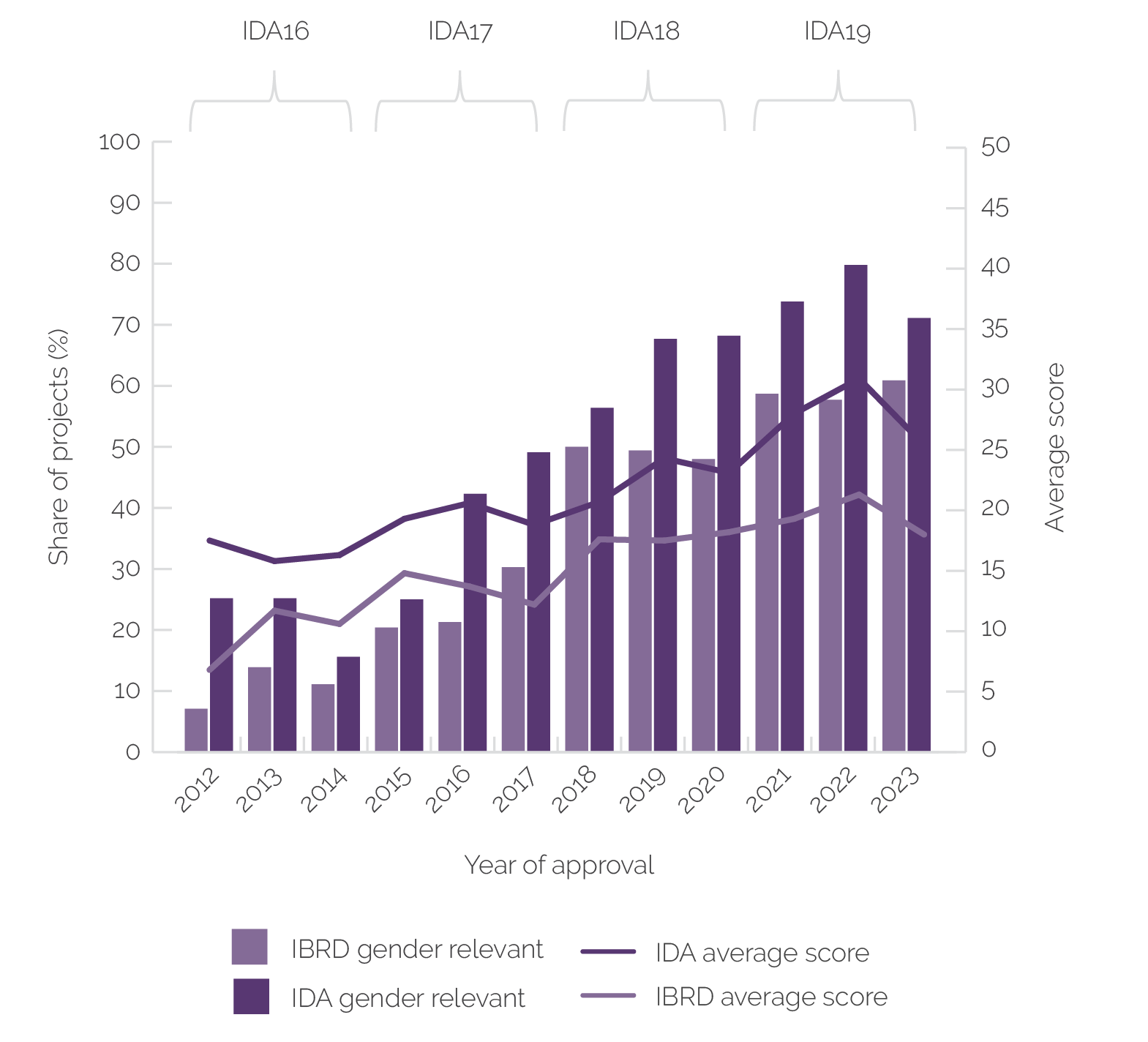

IDA plays an important role in supporting gender-relevant projects. The share of gender-relevant projects among IDA projects is systematically higher than among IBRD projects (figure 2.5) throughout the evaluation period. Moreover, the share of gender-relevant projects increased faster for IDA (especially under the 18th and 19th Replenishments of IDA) than for IBRD. In addition, IDA supports 86 percent of stand-alone projects compared with 71 percent of all gender-relevant projects and 55–60 percent of non-gender-relevant projects. The only countries with more than one active stand-alone project are two IDA beneficiaries—Bangladesh and Benin. In IBRD countries, the instruments used to finance stand-alone operations are mostly advisory services and analytics (ASAs) and DPOs, which are the main instruments supporting gender in these countries.4

Figure 2.5. Gender-Relevant Projects for the International Development Association and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, Fiscal Years 2012–23

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: The total number of projects is 3,836. The entire population of IBRD and IDA projects (investment project financing, Programs-for-Results, and development policy operations) is included. Additional financing is counted separately, but additional financing of parent projects approved before 2012 is excluded. Gender relevance is defined based on the greater than 15 threshold. IBRD = International Bank for Reconstruction and Development; IDA = International Development Association; IDA16, IDA17, IDA18, IDA19 = 16th, 17th, 18th, 19th Replenishments of IDA.

The share of projects with low, moderate, and high gender relevance all increased, but with the largest increase in the least gender-relevant projects for World Bank lending and IFC investments and the smallest increase in the most gender-relevant projects. Between 2012 and 2023, the share of World Bank projects—investment project financing (IPF) and Program-for-Results financing—with a 20–25 gender intensity score increased from 5 percent to 27 percent, and those with a 30–35 gender intensity score increased from 5 percent to 25 percent. By contrast, the share of projects with a score higher than 55 increased only from 2 percent to 3 percent (figure 2.1, panel a). By 2023, almost all World Bank projects had at least some gender-relevant element, but those addressing gender inequalities in a more substantial way did not increase much and still represented a small percentage. Projects with a score of 20–25 generally have an indicator that tracks the percentage of female beneficiaries and may include consultations and sensitization activities or training that target women to increase their inclusion, but they do not address gender inequalities more broadly. Projects with the highest scores are either gender stand-alone projects (addressing gender inequalities is part of their project development objectives [PDOs]) or projects that include a gender component. Gender-transformative projects are more likely to have higher scores. Highly gender-relevant projects integrate a gender analysis in the context analysis and rely on a theory of change to address gender inequalities with explicit expected results. They also include gender-relevant indicators to measure the achievement of expected gender results. Figure 2.2, panel a, shows this general trend for the World Bank. As the cutoff defining gender relevance moves from greater than 15 to greater than 25, the trend line still shows an increase over time, but it becomes flatter, indicating that the highly rated projects increased at a slower rate. For IFC investments, the trend is similar: lower-rated projects increased the most (figure 2.1, panel c). The review of projects in the country case studies confirms this general trend of breadth over depth. In all case studies, the proportion of gender-relevant projects dramatically increased after the adoption of the FY16–23 gender strategy, but projects with a high quality of design (that is, with gender-transformative elements, integration of intersectionality, and evidence-based theory of changes) were still a minority at the end of the evaluation period—with differences among countries.

Against the trend in World Bank and IFC investments, IFC advisory work selectively focused its engagement on a subgroup of substantially gender-relevant projects. In IFC advisory services, the share of projects with a 0 gender intensity score did not decrease that much over the evaluation period; however, at the other extreme, the share of projects scoring 55 or higher increased from 2 percent to 23 percent (figure 2.1, panel b). The expansion of gender-relevant projects coincides not only with the FY16–23 gender strategy but also with the IFC Gender Secretariat being assigned to the Economics and Private Sector Development Vice Presidential Unit5 in 2016 to expand its role and influence and institutionalize gender equality as a core element of the IFC business strategy.

The gender tag likely contributed to the increase of gender relevance of World Bank projects, mostly by raising the share of low-score projects. The gender tag, introduced by the World Bank in FY17, was part of a plan to promote a more strategic and selective approach to addressing gender inequalities, in line with the intent of the FY16–23 gender strategy.6 The original target was to tag 55 percent of projects. Several Regions, however, independently raised the bar of gender tagging beyond the initial official requirements. For example, the Middle East and North Africa Region set a formal target of 65 percent by FY20 and 70 percent by FY23. Other Regions set even higher targets, if not formally up to 100 percent. According to most key informants, these targets did not match the resources mobilized to help project teams include appropriate actions (based on rigorous analysis) aimed at addressing gender inequalities, which resulted in a substantial effort spent on tagging.7 According to key informants, such high targets are also unrealistic because they view a proportion of World Bank projects as simply not conducive to reduce gender inequalities. As a result, the gender tag, whose implicit standard was not particularly stringent when it was introduced, became even more generous over time. Figure 2.2, panel a, shows that the percentage of gender-tagged projects initially corresponded to the percentage identified by the greater than 15 cutoff value of the gender relevance score but ended up corresponding to the lowest possible cutoff value in FY23 (score greater than 0). The strong push to tag could be satisfied only by progressively increasing the share of projects with “light” gender relevance. Thus, the minimum standard increased overall, but the share of projects designed to address gender inequalities in a substantial way did not increase to the same degree.

In IFC advisory services, lower gender flag targets and less pressure to meet them likely facilitated the strong focus on increasing the most relevant projects. IFC advisory services had a lower formal target of flagging,8 at 30 percent of the projects in FY16. As a result, IFC focused on increasing the share of the most promising and meaningful projects, and the share of advisory projects with the highest gender-relevant scores increased substantially. Key informant interviews highlighted several reasons for this positive trend: the growing importance of the Gender Group within the institution, Gender Group management placing a stronger emphasis on developing fully dedicated gender advisory solutions, and the increased presence of gender experts, particularly in the East Asia and Pacific and the Middle East and North Africa Regions. IFC case studies show that stand-alone projects tend to benefit from the support of gender experts during design and implementation. IFC recently increased the target to 50 percent for FY24. According to key informants, the corporate pressure to flag more projects is only now increasing. This requires hand-holding on gender flagging for industries that have fewer resources allocated to gender equality.

Making IFC investment projects more gender relevant has been challenging. The institutional focus on increasing the share of gender-relevant investments was mainly driven by the capital increase commitments9 that set up gender indicators; flagging targets for gender-relevant investments was, therefore, not set until recently. Unlike for IFC advisory services, IFC did not set a corporate target for gender-flagged investment projects for most of the evaluation period. The lack of corporate metrics and targets might have contributed to the lower flagging. The analysis of data and interviews also suggests that it has been quite difficult to include gender-relevant investments at the industry level—except for access to finance10 —which explains why few investments were flagged and most had weak gender-relevant scores. Challenges cited are limited capacity and resources, lack of sex-disaggregated client data, an unclear business case for clients, and uneven management attention. IFC recently introduced a target for the gender flag at 40 percent by FY24;11 according to key informants, further increases in targets will be challenging to meet for some industries, such as infrastructure and manufacturing, without a corresponding increase in capacity and resources.

According to World Bank and IFC staff, the increased share of gender-tagged and gender-flagged projects helps generate awareness on the importance of addressing gender inequalities and the potential of operations to reduce them. The gender flag and especially the gender tag were not successful in replacing earlier nonselective gender mainstreaming with a more selective and focused approach to addressing gender inequalities. However, 57 percent of World Bank staff who answered the IEG survey consider the gender tag useful or very useful, and 85 percent of IFC staff think the same of the gender flag. Most staff, including those who are more critical of the gender tag and the gender flag, recognize that they are an effective awareness-raising tool that increased the visibility of the gender agenda, foster buy-in at all levels, and “help people think about entry points in projects.” Those who express a more positive opinion also stress that these tools supported the articulation of a theory of change for gender equality and identification of specific activities.

At the same time, staff note that the pressure to increase the share of tagged and flagged World Bank and IFC projects beyond the institutions’ ability to ensure meaningful gender integration risks diluting the mandate. A World Bank gender expert expresses an opinion voiced by many staff members, “I do not think the [World] Bank should be 100 percent tagged…. The tag was a useful target, it increased [the Bank Group] ambition, and now it needs to be revised again because otherwise we are only ensuring that everyone is doing the bare minimum…. If everyone is getting [the gender tag], then we need to look at the quality of the tag and start setting criteria of whether your project is transformative or just gender aware [and] maybe create some ‘level [or] depth’ of approach, not just breadth.” Another expert adds, “There is ‘crazy’ gender tagging…. The 100 percent mandate diverts the discussion on seeking solutions that are impactful.” Similarly, an IFC gender expert states, “The gender flag is problematic. A push to flag every project…is not very meaningful. We need to rethink and revisit that.”

Despite obvious improvements in Bank Group engagement in gender equality since 2012, three main unresolved issues threaten its achievement. First, the greater focus on quantity, as opposed to quality, of the engagement translates into a limited number of projects with gender-transformative elements, attention to context-specific conditions and intersectionality, and robust theories of change. Second, Bank Group incentives focus more on individual projects, with the World Bank maximizing the number of projects addressing gender inequalities. Yet no equally strong incentives or resources are devoted to fostering a country-driven approach. The new 2024–30 gender strategy is aware of the delays in advancing the country-driven approach and makes this a main priority. Third, gender engagement incentives and resources tend to emphasize design over implementation, even though implementation is critical to maintaining the gender relevance of the intervention and achieving results. Chapter 3 explores this issue further.

The gender stand-alone projects only moderately increased in the World Bank lending portfolio and IFC investments. Gender stand-alone projects are defined as those whose PDO(s) explicitly addresses gender inequalities.12 They include operations that entirely focus on advancing gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls and sectoral projects that explicitly address gender inequalities as one of their PDOs, such as an education project addressing gender inequality in schooling. The gender stand-alone projects tend to be those with the highest gender relevance scores. These projects can adopt multisectoral, holistic approaches to advance gender equality. They can be a key vehicle to address root causes of gender inequalities and provide great learning opportunities (see appendix E). The World Bank gender stand-alone operations represented 1.5–5 percent of all projects before the FY16–23 gender strategy and slightly increased to 2–7 percent after the strategy. Most stand-alone projects were found in the Human Development Practice Group (79 percent), whereas Equitable Growth, Finance, and Institutions; Sustainable Development; and Infrastructure had much lower shares (9, 12, and 1 percent). Even without considering maternal health projects, the share in Human Development was 56 percent and in Equitable Growth, Finance, and Institutions; Sustainable Development; and Infrastructure 17, 25, and 2 percent. IFC stand-alone investments are even fewer (less than 1 percent of the total investment portfolio), and all of them are in the Financial Markets industry group. In IFC advisory services, gender stand-alone projects were only 0–2 percent before the strategy, but they increased to 4–13 percent of all projects after the strategy.

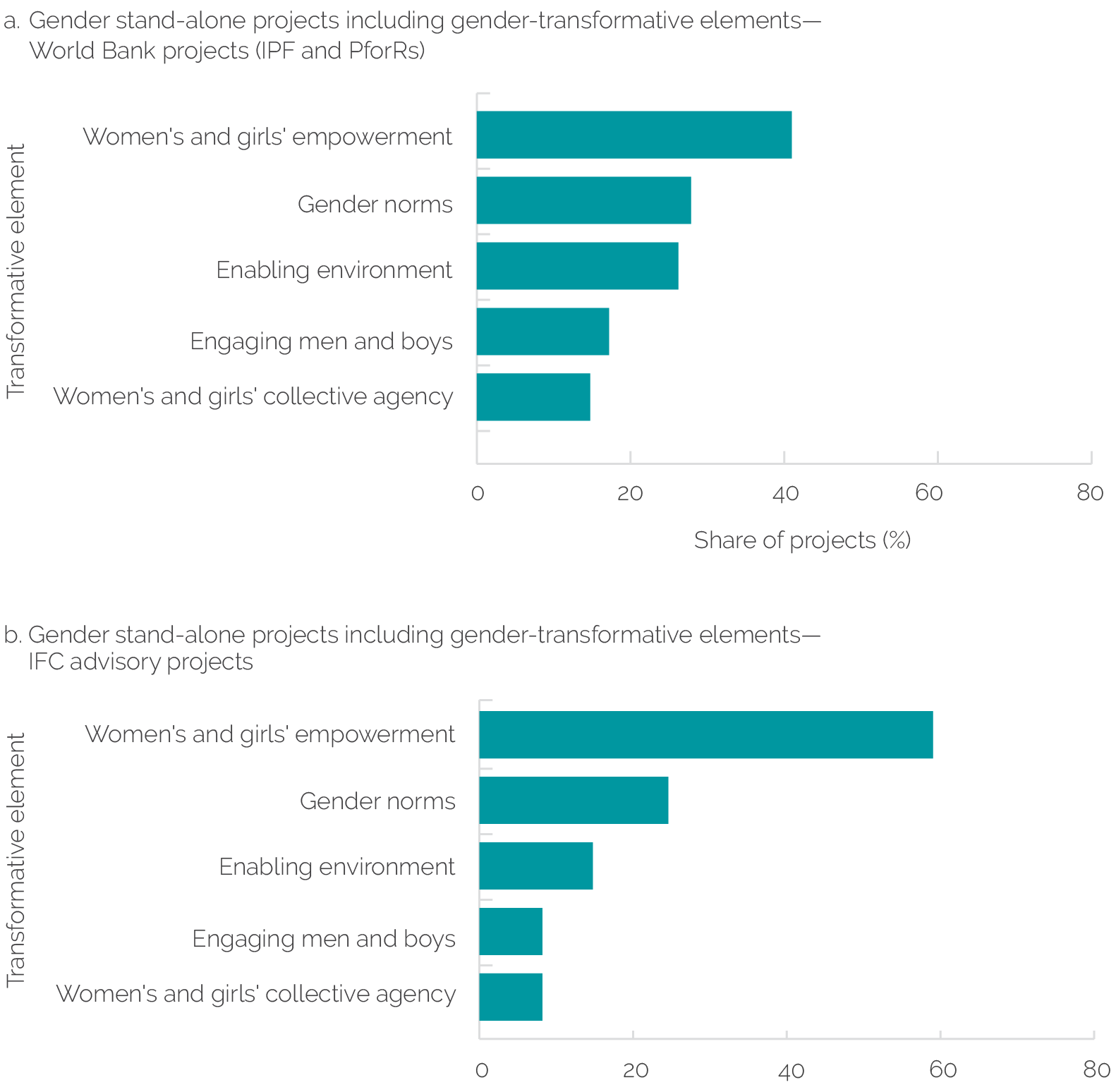

After the adoption of the FY16–23 gender strategy, an increasing but still limited number of operations included gender-transformative elements. Gender-transformative interventions aim to address the root causes of gender inequalities by transforming gender norms, roles, and relations, while working toward redistributing power, resources, and services more equally (UNFPA 2023). Gender stand-alone projects are expected to be more gender transformative than other projects, but almost half of World Bank stand-alone projects do not include any gender-transformative elements, and only 4 percent include all the transformative elements identified through the portfolio review. Only 40 percent of gender stand-alone projects support women’s empowerment, and even smaller percentages aim to transform gender norms and improve the enabling environment (formal institutions) for gender equality (figure 2.6, panel a). The gender-transformative projects tend to be recent, especially those supporting improvement in the (formal) enabling environment, engaging men and boys, and promoting women’s and girls’ collective agency. IFC stand-alone interventions mostly support the empowerment of women and girls but pay limited attention to transforming gender norms, engaging men and boys, and promoting collective agency (figure 2.6, panel b). Country case studies confirm an increase in projects with gender-transformative elements, but they are still a minority.

Figure 2.6. Gender-Transformative Elements in World Bank and International Finance Corporation Gender Stand-Alone Projects

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: The figure shows the percentage of World Bank IPF and PforR (N = 122) and IFC advisory (N = 69) gender stand-alone projects with specific gender-transformative elements. IFC investments were not included because of the low number of stand-alone interventions (N = 14). IFC = International Finance Corporation; IPF = investment project financing; PforR = Program-for-Results.

The World Bank and IFC gender-relevant portfolios inadequately address intersectionality issues, resulting in insufficient recognition of the diverse needs and types of discrimination faced by specific social groups of women. The gender-relevant portfolio does not sufficiently consider the intersection between gender inequalities and other types of social inequalities. The needs and constraints of specific social groups of women (women of different ages, ethnic groups, and so on) are frequently not diagnosed and addressed. Only 22 percent of World Bank gender stand-alone projects (IPFs and Programs-for-Results) consider intersectionality issues, with poverty and age (in the case of projects focused on education and sexual and reproductive health) being the two most common characteristics considered. Similarly, IFC stand-alone projects treat women as a homogeneous group—only 17 percent of them adopt an intersectionality lens.

For IFC, the adoption of an intersectionality lens remains limited and primarily focuses on economic or geographic differences, such as income level, rural or urban location, and informal or formal occupation. Considering the intersection between gender and ethnicity, age, or disability is often constrained by lack of sex-disaggregated data. The Latin America and the Caribbean Region stands out for increasing attention to intersectionality in projects. For example, in Colombia and Peru, two financial institutions with support from IFC are redesigning their lending products to address migrant women’s needs and constraints. The projects also address the internal sociocultural bias against migrant women through capacity building. In Mexico, IFC is focusing on LGBT+ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people) and persons with disabilities (following the model of the Sri Lanka Together We Can Plus initiative) to enhance the employment practices and human resources policies of companies, but it is not paying attention to the intersection between disability and gender.

For the World Bank, case studies show still low but increasing attention to intersectionality. Several projects aim to include women and other disadvantaged social groups—such as youth, persons with disabilities, and disadvantaged ethnic groups—but consider women as a homogeneous group and disregard social inequalities among women or gender inequalities within the other social groups. In the country case studies, the main intersectionality issues considered by the World Bank relate to poverty, marital status (social protection projects target female heads of household), age, and geographic areas (many projects aim to increase access to social services for women and girls living in rural or underserved areas). Other types of intersectionality issues—such as fragility, conflict, and violence (FCV); ethnicity; migration; and SOGI—are successfully addressed in some cases. In Bangladesh, the Health and Gender Support Project for Cox’s Bazar District addresses gender inequalities among FCV-affected women and girls—in particular, sexual and reproductive health needs and GBV among Rohingya refugees. Conversely, in Uzbekistan, gender inequalities among the FCV-affected population (in particular, refugees from Afghanistan) are overlooked in the gender-relevant portfolio. A special focus on migrant and Indigenous women was found in the Peru portfolio and, to some extent, in some projects in Mexico. Two good examples of the application of intersectionality are the Saweto Dedicated Grant Mechanism for Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities in Peru Project, which adopted a bottom-up and culturally sensitive approach to addressing gender inequalities in Indigenous communities, and the Australian Gender Pillar in Viet Nam, which supports the integration of a SOGI perspective in the new gender equality law.

The Bank Group has been developing a SOGI agenda since 2016, but work in this area is still nascent. This evaluation did not analyze in depth the Bank Group engagement to promote the rights of people with diverse SOGI because this aspect had not been included in the FY16–23 gender strategy. Including SOGI in the engagement for gender equality is still controversial among the World Bank and IFC staff interviewed. For some key informants, the SOGI agenda is part of social inclusion, and it is treated as such in most of the World Bank and IFC initiatives. For some key informants, it should be integrated in the engagement for gender equality. A third group of key informants underscores that including SOGI in the gender equality agenda is not advisable at the moment in many countries, which consider it taboo, and that the World Bank does not have enough knowledge and skills to address SOGI issues. This evaluation finds some good practices in addressing SOGI in some SOGI-sensitive countries—for example, the inclusion of SOGI in the Thailand Country Partnership Framework (CPF), the regional SOGI inclusion in the Latin America and the Caribbean ASA, and the successful collaboration between the World Bank and SOGI associations in policy dialogue to support the integration of SOGI in the new Viet Nam gender equality law. IFC is focusing on increasing awareness and education around LGBT+ inclusion and providing targeted support to industries on accessibility. In IFC, the focus on SOGI is limited to a few interventions that aim to build internal knowledge and guidance for interested clients and to raise awareness through peer learning platforms. In Mexico, an IFC peer learning platform focuses on LGBT+ and persons with disabilities as part of raising awareness to improve workplace environments.

The strength of the theories of change varies across projects. Theories of change have become stronger in some projects (for example, in stand-alone interventions, including in IFC advisory projects) because of an increased use of knowledge. Nevertheless, in many projects, the theory of change is weak, with activities and expected results found not relevant or only partially relevant. This point is developed further in chapter 3.

Toward a Country-Driven Approach

The Bank Group identifies the country-driven approach as fundamental to addressing gender inequalities and has made efforts to strengthen it. The FY16–23 gender strategy aimed to deepen the country-driven approach.13 According to the strategy, this approach “allows for the agenda to be customized to the specific country situations…. This means that objectives to promote gender equality are set at the country level, rather than globally” (World Bank Group 2015, 62). To achieve this goal, the gender strategy decided to adopt a more systematic approach to the generation and use of data and knowledge at the country level and strengthen the Bank Group’s “connective tissue between its gender equality objectives at the country level and the instruments to address these objectives” (World Bank Group 2015, 66). The strategy recognized the role of Country Management Units in framing the contribution of different instruments to the country’s gender priorities (World Bank Group 2015). The new 2024–30 gender strategy reiterates that the Bank Group should deepen its country-driven approach to gender equality and ensure that the objectives to promote gender equality are set at the country level (World Bank Group 2024).

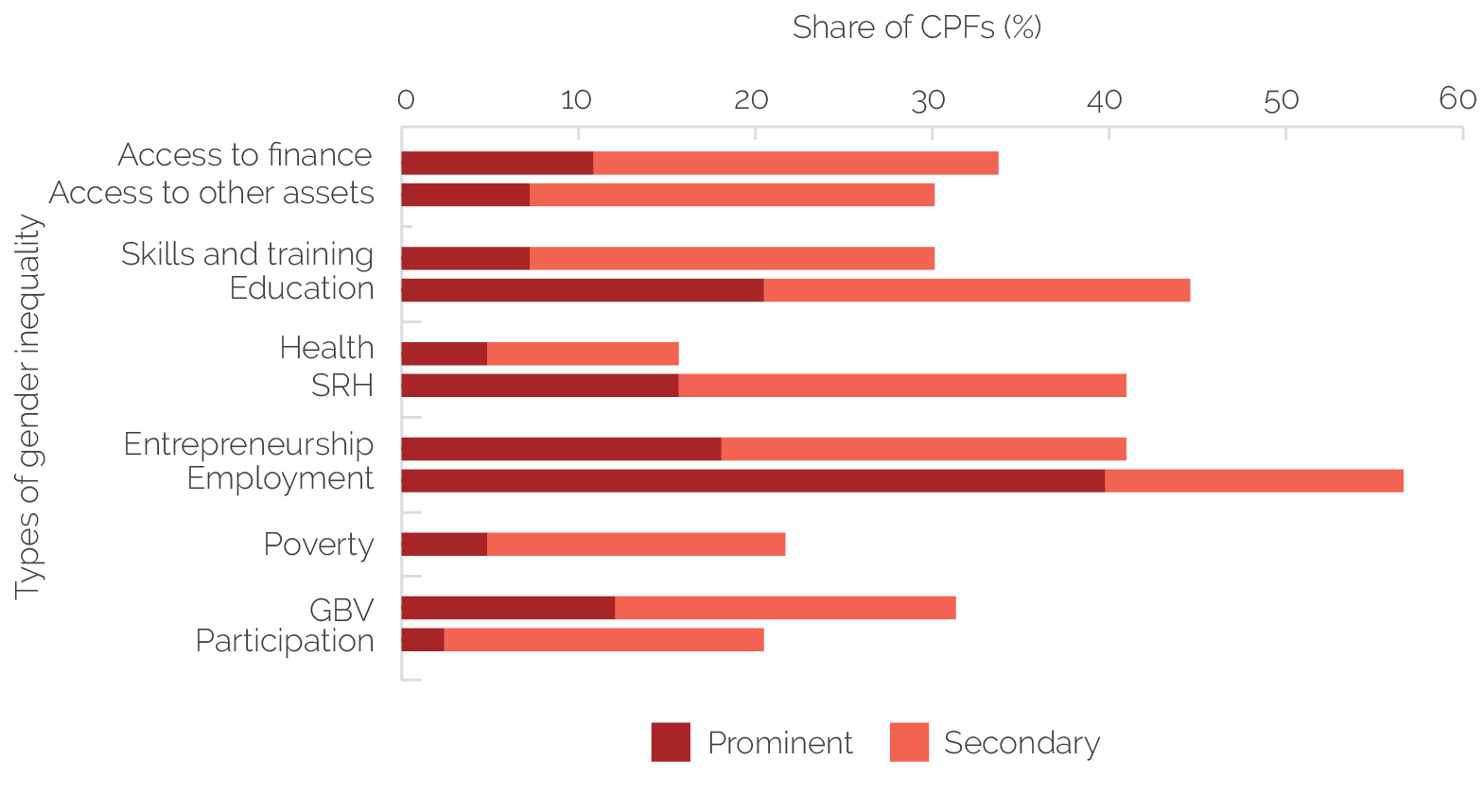

Most country strategies explicitly identify and prioritize gender inequalities. Thanks to robust diagnostics, 83 percent of the CPFs reviewed clearly identified at least one gender inequality to be addressed as part of the strategic country-level engagement, although only 49 percent explicitly mention gender inequalities in their objectives. Almost 60 percent of CPFs indicate addressing gender inequalities in the labor market as a priority—40 percent as a prominent one (figure 2.7). This is by far the most common gender priority, followed by addressing inequalities in education, entrepreneurship, and sexual and reproductive health. The increased focus on specific gender inequalities is an improvement with respect to previous IEG analysis. According to an analysis of gender integration in country strategies (World Bank 2016b), before the introduction of the Systematic Country Diagnostic (SCD), one-third of country strategies only generically mentioned gender as a cross-cutting issue. Moreover, even the sporadic cases in which gender equality was a strategic objective provided no information on how the gender objectives had been selected based on the diagnostic work and how they related to the other objectives of the country strategy.

Figure 2.7. Country Partnership Frameworks That Address Specific Types of Gender Inequality as Prominent and Secondary Priorities

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: The graph represents the percentage of the 83 CPFs reviewed that address specific gender inequalities. Each CPF can address multiple priorities, either as a prominent or a secondary one. Each bar represents a total percentage; for example, 30 percent of CPFs address gender inequalities in skills and training—7 percent as a prominent priority and 23 percent as a secondary focus. CPF = Country Partnership Framework; GBV = gender-based violence; SRH = sexual and reproductive health.

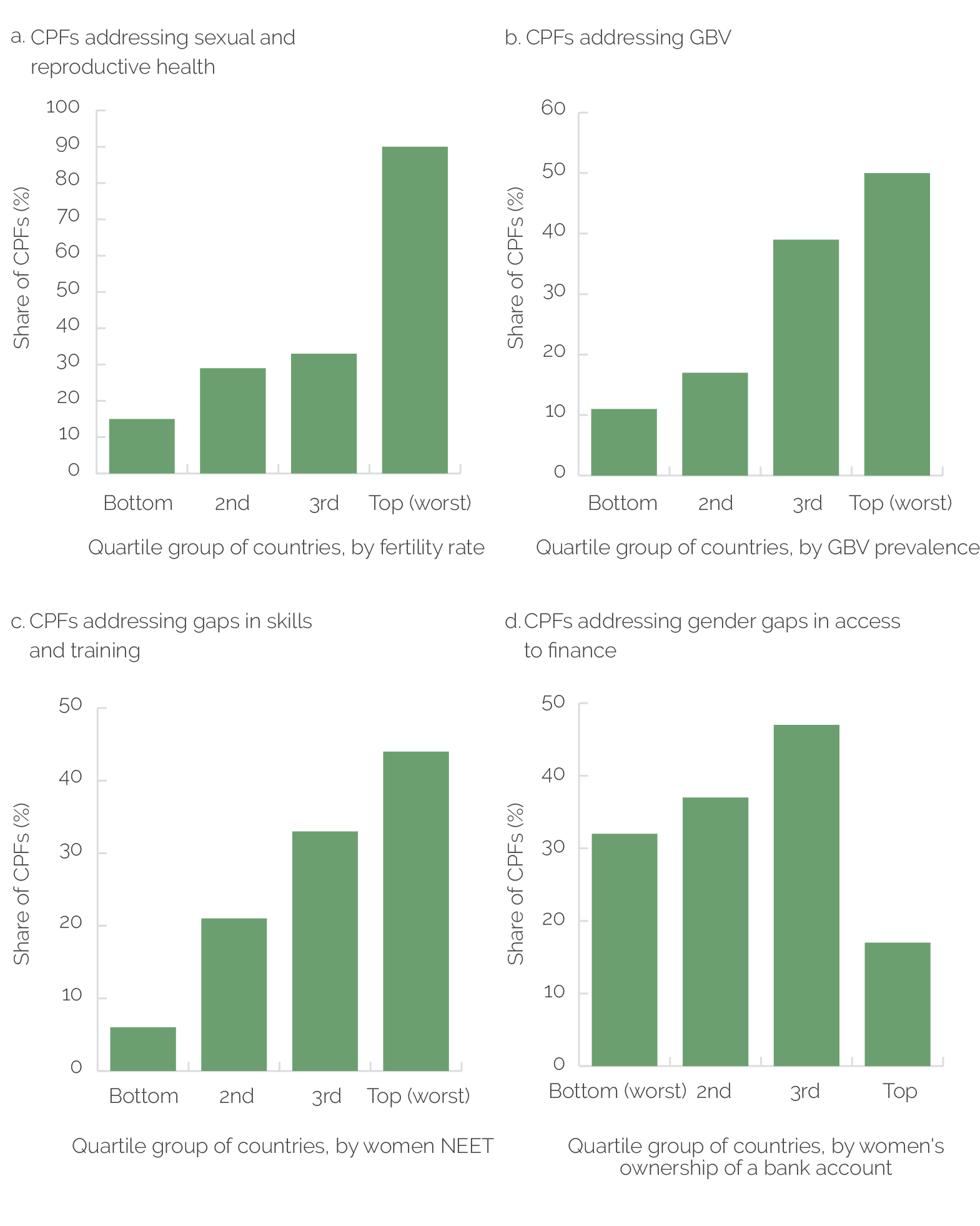

The gender priorities identified in country strategies align well with country needs. CPFs focus on the most pressing gender issues that the country faces according to relevant country-level gender statistics. Countries that are more likely to select sexual and reproductive health as their focus, for example, are those with the highest fertility rates—90 percent of CPFs that identify sexual and reproductive health as their key priority belong to countries in the top quartile of fertility rate (figure 2.8, panel a). Similarly, CPFs that identify GBV as a priority are disproportionately more likely to be of those countries where GBV is more acute (figure 2.8, panel b). This alignment is detectable for most gender inequalities and gender statistics. Figure 2.8 shows 4 out of 10 pairs of CPF priority-country statistics that the evaluation constructed as part of the analysis of CPF gender priorities alignment with country needs. Access to finance (figure 2.8, panel d) is less aligned than the others, perhaps because promoting access to finance through formal financial institutions requires a certain level of development in financial markets.

Figure 2.8. Association between Country Partnership Frameworks’ Gender Priorities and Country Gender Statistics

Sources: Independent Evaluation Group; World Bank Gender Data Portal (accessed January 2024).

Note: Quartiles of GBV prevalence are based on the following statistics: proportion of women subjected to physical and sexual violence in the last 12 months (modeled estimate; percentage of ever-partnered women 15 years of age and older); they cover 72 countries. Quartiles of women NEET are based on the following statistics: share of youth NEET, female (percentage of female youth population); they cover 73 countries. Quartiles of fertility rate are based on the following statistics: fertility rate, total (births per woman); they cover 82 countries. Quartiles of women’s ownership of a bank account are based on the following statistics: financial institution account, female (percentage; 15 years of age and older); they cover 75 countries. CPF = Country Partnership Framework; GBV = gender-based violence; NEET = not in education, employment, or training.

Despite a clear improvement in the identification of country gender priorities, most CPFs lack an operational strategy to address them. The CPFs do not typically elaborate on how the stated gender equality objectives should be achieved. Projects are mapped to CPF gender-relevant objectives, but, generally, there is no explanation of how these projects, either individually or collectively, would contribute to achieving the CPF gender goals as part of a coherent country-level theory of change. Moreover, few country strategies include measurable indicators to monitor achievements (as discussed in chapter 3). Most commonly, each project operates based on its own individual theory of change to achieve its PDOs, and the CPFs use project-based indicators to measure achievement of CPF objectives. The achievement of gender-relevant priorities remains assigned to the project rather than to the country program.

Promising practices of country-driven engagement observed in country case studies demonstrate the Bank Group’s increasing capacity to coordinate instruments and activities strategically around country gender priorities and the merit of this approach. Bangladesh, Benin, Egypt, Mexico, and Viet Nam are all examples of countries where gender experts and gender champions—supported by managers—contributed to the production and use of robust evidence to underpin policy dialogue, which successfully resulted in the identification of gender priorities for the country and the inclusion of a gender pillar in a DPO. In Viet Nam, for example, the financial resources of the Australian Gender Pillar, continuous support of a World Bank senior gender expert, and strategic production and use of knowledge allowed the World Bank to remain engaged in policy dialogue on gender equality and support relevant law reforms, including the reform of the labor code and the law on gender equality. IFC’s country program in Sri Lanka launched in 2017 is a holistic engagement that addresses gender inequalities based on a comprehensive theory of change (box 2.2). These promising practices embed the spirit of the country-driven approach but have limitations—few instruments are coordinated, whereas the rest of the portfolio is still scattered.14

Box 2.2. The International Finance Corporation’s Sri Lanka Country Gender Program

The International Finance Corporation (IFC) launched its largest country-based gender program in Sri Lanka in 2017. The engagement allowed IFC to adopt a more holistic approach to identifying and addressing gender gaps based on a unified theory of change consolidated across sectors and industries. This approach proved to be effective in influencing the broader private sector ecosystem, which contributed to improvements in the working environment for women employees, leaders, and entrepreneurs.

The program included 12 projects across five of IFC’s industries, including Banking on Women, Women’s Insurance Program, Tackling Childcare, a peer learning network (SheWorks Sri Lanka), and Economic Dividends for Gender Equality (EDGE) certification. By combining different modalities of engagement, such as peer learning platforms and the promotion of regulatory and legislative change, IFC was able to tackle complex problems, such as childcare. The program also influenced the development of other country-level gender programs in Indonesia, Kenya, and Tanzania.

A key enabling factor for the success of the program was the presence of a lead gender expert and team dedicated to managing program implementation. However, this IFC country-level approach was very resource- and labor-intensive, was reliant on donor grant funding, and had monitoring and evaluation frameworks not designed to capture impacts beyond IFC direct engagement.

Source: DFAT 2022.

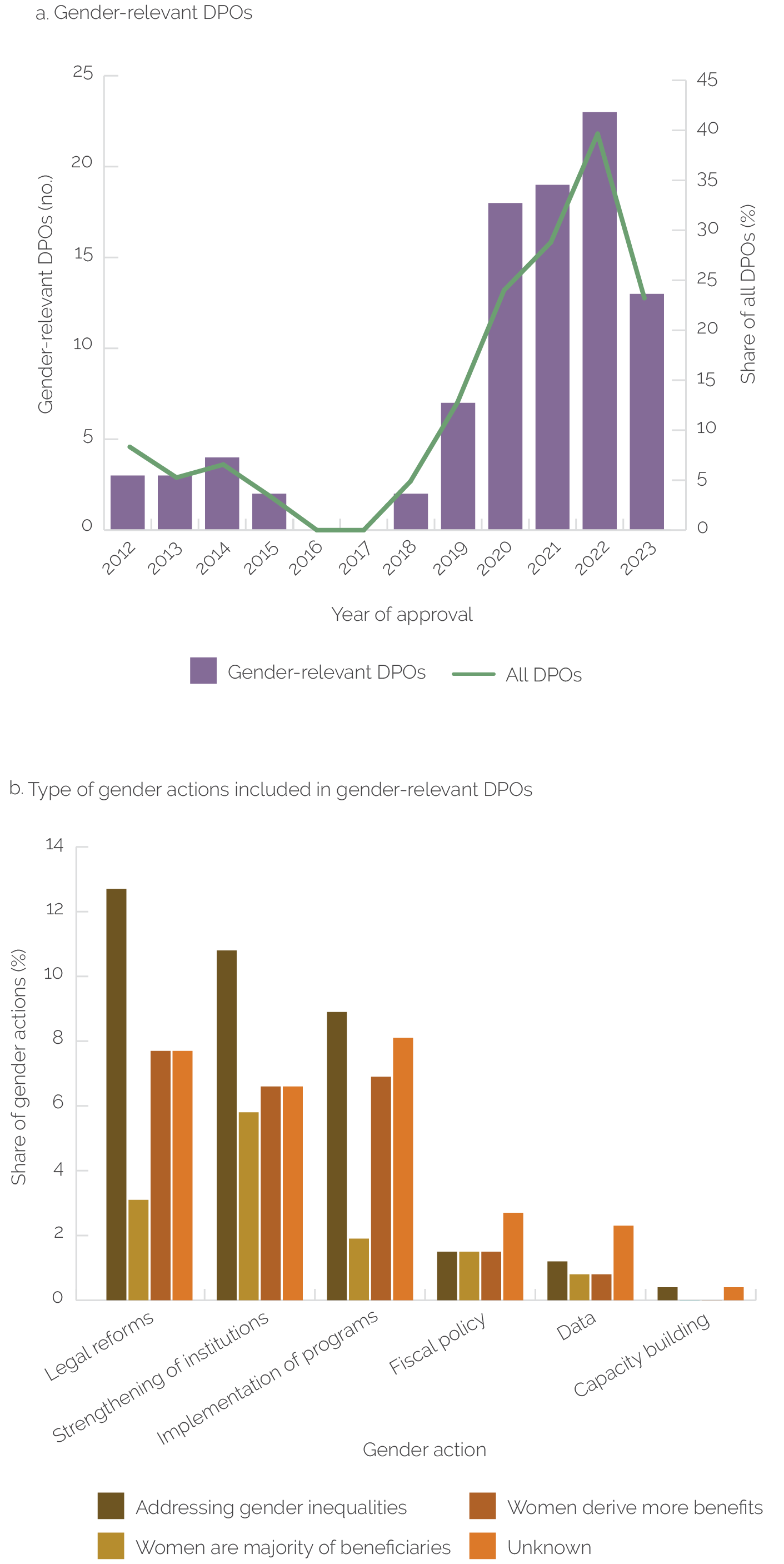

After the gender strategy, DPOs have been increasingly used to promote gender actions that reduce gender inequalities. The 95 gender-relevant DPOs reviewed for this evaluation include 259 gender actions—that is, specific activities to address a specific form of gender inequality (see appendix E). Gender actions were identified based on what the prior actions of the DPO committed the country to do to address gender inequalities. For example, in Colombia, a prior action aimed to enact measures that (i) prohibit discrimination against women’s access to employment and (ii) increase the length of paternity leave, introduce shared parental leave, and allow parental leave to be taken on a part-time basis to encourage the sharing of responsibilities for unpaid care work and to support women’s economic empowerment. DPOs engage in a broad array of gender actions, mostly legal reforms, institution strengthening, and implementation of programs. The majority of gender actions directly aim to address gender inequalities (for example, reforms that introduce protection services for victims of domestic violence). Other gender actions target specific groups of women (for example, female displaced persons) or adopt “neutral” policies that disproportionately benefit women as they are the majority of the target group (for example, part-time workers). In some cases, it is not possible to determine whether the prior action is gender relevant (figure 2.9, panel b). In addition, there has been an increase in the use of DPOs to intensify engagement with governments on gender issues. Gender-relevant DPOs accounted for only 5 percent of the total DPOs before the gender strategy, but this number increased to 40 percent in FY22 (figure 2.9, panel a).

Figure 2.9. Prevalence of Gender-Relevant Development Policy Operations and Type of Gender Actions

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: The analysis covers 259 gender actions in 95 gender-relevant DPOs identified based on a greater than 15 cutoff value of the gender-relevant score approved between fiscal years 2012 and 2023. DPO = development policy operation.

Gender platforms play an active role in supporting policy engagement for gender equality. Gender platforms15 have proven to be critical instruments to foster engagement for gender equality at the country level. They have helped define operational and analytic work under the CPF, monitor and assess the portfolio of activities, identify gaps and opportunities for sharing knowledge internally and externally, and promote collaborations and policy dialogue with the government and other stakeholders. For example, one of the objectives of the gender platform in Bangladesh—a stand-alone ASA—is to foster policy dialogue in the country. The platform benefits from an operational comprehensive view of gender activities, including lending, advisory, and knowledge, which allows for effective coordination with the government. A DPO, for example, included a trigger to establish grievance mechanisms enabling workers to anonymously report sexual harassment. Subsequently, the gender platform negotiated technical assistance with the Ministry of Labor and Employment to strengthen this mechanism and to ensure that it is implemented effectively. The platform also coordinated with the Ministry of Women and Children Affairs to align the World Bank portfolio with the government’s gender priorities. Despite coordination challenges because of the ministry’s low capacity, the current Health and Gender Support Project for Cox’s Bazar District and a potential follow-up GBV project demonstrate the continuity of the policy dialogue.

The commitment of gender champions—both task team leaders (TTLs) and management—and the use of knowledge have contributed to the effectiveness of policy dialogue, even in the absence of gender platforms. For example, in Benin, the TTL of the Unlocking Human and Productive Potential DPO series (which includes empowering women and girls among its PDOs), supported by managers, successfully established a collaboration between the Macroeconomics, Trade, and Investment; Health, Nutrition, and Population; and Poverty and Equity GPs for a fruitful policy dialogue with the government and for design of the operation. In Egypt, the presence of a committed and experienced gender focal point, the use of robust country diagnostics on women’s economic empowerment, and the strong involvement of the National Council for Women in the negotiation with the government helped enable the integration of a gender pillar in the Egypt Inclusive Growth for Sustainable Recovery DPO.16

IFC has increased its efforts to engage with business networks on gender equality. IFC has increasingly engaged in peer learning platforms17 to complement its client work and expand IFC’s reach beyond individual clients. Peer learning platforms are a convening mechanism designed and facilitated by IFC to bring companies together to share knowledge and implement best practices on gender equality to address specific inequalities and share knowledge and best practices among peers. Through the platforms, companies make between one and three commitments to close gender gaps in their operations.

These encouraging examples notwithstanding, the evaluation finds that the approach to gender equality was still fragmented at the end of the evaluation period, with gaps in systems and processes for coordination at the country level. The instruments, sectors, and institutions assigned to operationalize gender priorities remain disconnected. The prevalent Bank Group approach to address gender inequalities is still project-by-project rather than a strategic, focused, and coherent approach—not dissimilar today from what the Mid-Term Review described: “Absent appropriate prioritization of gender in the program, a diverse set of projects tagged and flagged for gender in the portfolio can appear to be ‘sprinkled’ rather than strategic” (World Bank 2021b, 23). Despite the FY16–23 gender strategy’s assertion that deepening the country-driven approach is the way for the Bank Group to take its support to gender equality to the next level,18 the operating modalities and systems of incentives still center on the project level and not the country level. Although instruments, sectors, and institutions generally align with country gender priorities, they are weakly coordinated (which results in missed opportunities and partial achievements). Examples of effective coordination among different instruments and sectors, driven by multisector gender stand-alone projects and DPOs, represent ad hoc experiences rather than an institutionalized approach. The individual efforts of gender champions primarily drive coordination and collaboration.

Despite the intent to strengthen the One World Bank Group approach, the collaboration between the World Bank and IFC is still limited and opportunistic. The evaluation finds only a few examples wherein a combination of analytic work, lending portfolio, technical assistance, and IFC investments and advisory services worked in sync—and in sync with World Bank activities—to achieve common gender equality objectives. One example is the collaboration between the World Bank and IFC to address the financial inclusion of migrant women from República Bolivariana de Venezuela in Peru, where the World Bank’s ASA Venezuelan Migration Policy Dialogue contributed to an IFC intervention targeting microcredit access for migrant women-led small and medium enterprises. The World Bank developed a training on conscious and unconscious bias related to migration and gender that was applied in the IFC project to mitigate its client’s staff biases against migrant populations, including women. However, in general, the collaboration between the two institutions is occasional and opportunistic. The analysis of CPFs indicates that a good IFC–World Bank collaboration tends to develop around specific activities that have little to do with the strategic engagement for gender equality.

The World Bank and IFC have collaborated on DPOs supporting legislative reforms and policy measures concerning labor laws, respectful workplaces, and childcare. These examples happened in Bangladesh, Egypt, Fiji, Myanmar, Sri Lanka, and Viet Nam. In Egypt, the World Bank and IFC collaborated on policy dialogue during a negotiation of the DPO that aimed at reforming the labor law to increase female labor force participation. In Sri Lanka, IFC’s work contributed to the finalization of the National Policy on Child Day Care Centers. In Fiji, IFC supported the government to establish the Early Childhood Care and Education Taskforce and draft an early childhood care services policy and regulation framework guidance.

Although good practices of coordination and collaboration with development partners exist, this coordination remains weak overall, constraining the potential of the country-driven approach. Several key informants highlight the importance of partnerships and coordination to leverage each other’s comparative advantage and work on gender inequalities, which is essential for an impactful country-driven engagement. External partnerships contribute to advancing the gender agenda—for example, the collaboration between the development partner group and women’s rights organizations to criminalize GBV in Uzbekistan, the Bank Group’s involvement in the GBV cluster for the Rohingya refugee crisis response in Bangladesh, and the joint development partner effort to create the 2023 Mexico Sustainable Taxonomy.19 However, most external coordination on gender equality has been sporadic. The World Bank is often absent from the tables of discussion and gender equality forums (which hampers the continuity of policy dialogue on gender issues and has resulted in missed opportunities of collaboration to increase impact). Addressing Gender Inequalities in Countries Affected by Fragility, Conflict, and Violence: An Evaluation of the World Bank Group’s Support came to a similar conclusion for FCV countries (World Bank 2023a). The new 2024–30 gender strategy recognizes the need to intensify coordination at the country level and identifies collective action as one of the three key elements in its theory of action.

The engagement with civil society organizations (CSOs), women’s rights organizations, local actors, and target groups is not systematic, hindering the ownership, effectiveness, and sustainability of Bank Group engagement for gender equality. The Bank Group follows procedures and processes to hold wide consultations for CPFs and projects. However, the actors involved in identifying and discussing the gender priorities, modalities, and results of this engagement are not clearly named. Several IEG evaluations (World Bank 2018, 2019a, 2023a) have highlighted the importance of engaging with civil society to foster inclusive ownership. Yet evidence collected through the case studies indicates that consultations for project design are irregular, with weak involvement of key actors at the national level and only occasional involvement of actors at the local, community, and citizen levels. Meaningful consultations increase the relevance and ownership of World Bank interventions and their potential effectiveness and sustainability (see chapter 3). The 2024–30 gender strategy highlights the need to strengthen partnerships with CSOs.

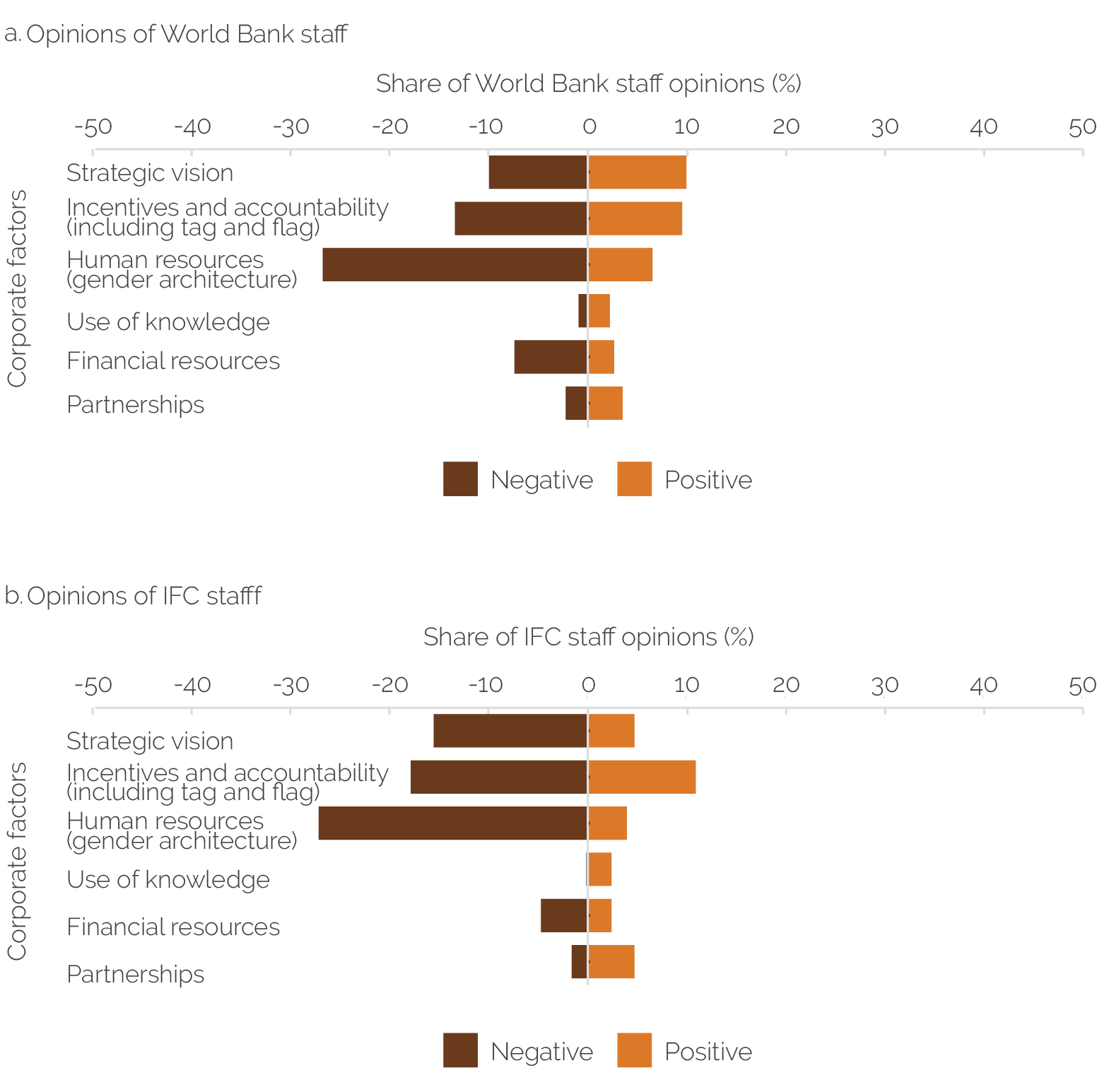

One of the main constraints on the effective operationalization of the country-driven approach is the current organization of the Bank Group’s gender architecture. World Bank and IFC staff widely cite shortcomings related to the availability, organization, and management of gender expertise (figure 2.10), and those shortcomings also emerge in country case studies. First, gender expertise in the World Bank is not sufficiently decentralized (during the evaluation period, IFC expanded its regional presence but continues to rely heavily on short-term consultants, which results in high turnover and limits continuity).20 For both the World Bank and IFC, a strong constraint on an impactful gender engagement is the absence of a gender expert in the country, with the necessary seniority, expertise, time, and knowledge of the context to support the country team in defining the country gender engagement strategy, advise project teams in designing and implementing projects, and support necessary internal and external coordination. The evaluation of gender in FCV raised the same issues for FCV-affected countries (World Bank 2023a). Second, there is no clear accountability for the country gender engagement. Roles and responsibilities regarding the identification and implementation of a country-level strategy of intervention for gender equality are not clearly defined, including who oversees the internal and external coordination activities. Third, the overall gender architecture is not clearly defined. Gender expertise sits at different levels within the Bank Group without clearly assigned tasks and responsibilities and without defined coordination mechanisms among the Gender Group, regional gender coordinators, Gender Innovation Labs (GILs), gender platforms or other similar mechanisms of support, gender leaders in GPs, and country and industry gender focal points. The evaluation finds confusion of roles, overlaps, gaps, and even competition for funds. Fourth, TTLs and country managers who are responsible for supporting the country engagement for gender equality often do not have the necessary knowledge and skills (see chapter 3). Finally, the gender tasks of the gender focal points in countries, Regions, GPs, and industries are often not budgeted—gender is considered a supplementary task. Concerns about the availability and management of human resources for gender equality engagement are cited as the most important by key informants (figure 2.10).

Figure 2.10. Corporate Factors Affecting World Bank Group Engagement for Gender Equality

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: The unit of analysis is 232 statements of World Bank staff and 129 statements of IFC staff from 50 (World Bank) and 33 (IFC) corporate interviews. World Bank and IFC staff were purposively selected based on their expertise and roles in gender-related work within the World Bank and IFC. Interviews were categorized using manual sentiment analysis for positive and negative responses to the same question. IFC = International Finance Corporation.

Critical Role for Knowledge

Robust diagnostics are used to produce CPFs that address specific gender inequalities. The FY16–23 gender strategy emphasized the role of knowledge generation and evidence-based approaches to inform operations and underpin policy dialogue. The evaluation finds that 67 percent of the most recent CPFs convincingly derive gender priorities from robust diagnostics of gender inequalities, and this percentage increases to 80 percent for those that rely on an SCD with strong analysis based on sex-disaggregated data. Similarly, in most country case studies, the last CPF identifies country gender priorities that hinge on a strong SCD informed by gender assessments or other knowledge. According to the results of the principal component analysis, after the adoption of the FY16–23 gender strategy, the quality of the gender diagnostic informing country strategies is the factor that has most influenced the overall quality of country strategies. As the SCD gets streamlined, ensuring that robust gender diagnostics are timely channeled into the CPF preparation becomes of paramount importance. The Country Private Sector Diagnostic is a recent joint World Bank, IFC, and Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency knowledge product used by IFC to identify and assess opportunities for private sector–led growth. Whereas 68 percent of Country Private Sector Diagnostics approved before the CPF analyze gender inequalities, only 45 percent of them identify specific actions to address gender inequalities within the private sector. The limited use of Country Private Sector Diagnostics in country strategies was also highlighted by the IEG Mid-Term Review (World Bank 2021b).

The World Bank’s increasing support to produce gender statistics has reinforced the engagement for gender equality with governments and paved the way to further World Bank and donor investments. The World Bank has, for example, funded data collection on GBV in Bangladesh and Peru, time use surveys in Benin and Viet Nam, and technical assistance on improving gender data production and dissemination of gender statistics in Benin. This increased data production has supported operational work aimed at closing gender inequalities. For example, the time use survey was used in Viet Nam by both the World Bank and IFC to inform policy dialogue and operations focused on childcare.

In recent years, the World Bank and IFC have increasingly used robust gender diagnostics in policy dialogue, most prominently to integrate gender actions in DPOs. The report 2021 Development Policy Financing Retrospective: Facing Crisis, Fostering Recovery found that rigorous analytic work to underpin DPOs helped influence policy dialogue and reforms (World Bank 2022b). This is confirmed by the DPO review conducted for this evaluation. About 77 percent of all gender prior actions are supported by analytic work. Examples of effective use of knowledge in policy dialogue come from the country case studies. The 10 Messages about Violence against Women in Peru report (World Bank 2019b) successfully contributed to the national policy dialogue and agenda setting around GBV prevention policies and efforts. In Bangladesh, Benin, Egypt, Mexico, and Viet Nam, robust knowledge produced by the World Bank and IFC supported the policy dialogue leading to the inclusion of a gender pillar or gender priority actions in DPOs. In Benin, for example, the findings of the Country Gender Assessment (World Bank 2021a) were integrated in the Country Economic Memorandum and used in policy dialogue and negotiations with the government for a gender pillar in a DPO series.

Women, Business and the Law in Egypt is a good example of how the World Bank and IFC use knowledge to spur policy reforms. Countries are increasingly using Women, Business and the Law to introduce equal opportunity laws and improve their global ranking and request World Bank and IFC technical assistance and support to do so. In Egypt, the publication of Women, Business and the Law 2016: Getting to Equal (World Bank 2015) was a turning point in the engagement on gender equality between the Bank Group and the government. It was used to promote reforms removing hour and sector restrictions on women’s participation in economic activities and calling for increased safety measures (such as safe transport) to support female labor force participation.21

Although the Bank Group has improved its analytic work on gender inequalities and on what works to address them, it has been less effective in operationalizing it—that is, using knowledge to integrate effective strategies of intervention in operations and guide project implementation. GILs have increasingly produced knowledge on what works to address gender inequalities in the different regions, and they have been strengthening their collaboration with project teams to integrate this knowledge in project designs. The evaluation found some good practices of gender-transformative projects that received GILs’ support in design. Nevertheless, the analysis of relevant knowledge produced in the country case studies, compared with the assessment of country case project portfolios, shows limited integration of the findings of this knowledge in projects. Several key informants who are project team members also emphasize difficulty in operationalizing knowledge products. The main reason is the gap in capacities and support. Only one-fourth of CPFs explicitly draw on evidence of what works to address gender inequalities and develop policy actions. As for operations, only 27 percent of World Bank stand-alone projects have explicitly used knowledge to inform the relevance and effectiveness of the theory of change, and only 16 percent have conducted and used assessments, studies, surveys, or data to inform implementation. IFC stand-alone projects demonstrate a significant application of knowledge in both design (90 percent) and implementation (91 percent). However, these figures drop to 48 percent and 38 percent, respectively, for non-stand-alone projects.

An increasing number of IFC global and country knowledge products makes the case for the private sector to address gender inequalities, with uneven success in transitioning from knowledge to operations. IFC has increasingly engaged in addressing new types of gender inequalities and invested in knowledge to build the business case to close gender gaps in, for example, housing finance, insurance, leadership, time use, GBV, ride-sharing, and digital platforms. IFC staff members are often encouraged to operationalize this knowledge into operations, but results have been mixed. In some areas, IFC has effectively transitioned from knowledge to action at the country and client levels through strategy development, guidance, upstream policy work, and advisory services. For example, the IFC Tackling Childcare program set the groundwork for IFC engagement in childcare advisory and exploration of pathways to investments. The program led to the development of guidelines to implement child support in partnership with more than 30 organizations. IFC’s knowledge products in Bangladesh and Fiji were instrumental in the development of policy reforms. In housing finance, IFC conducted housing market studies in 2021 that led to a significant increase in IFC’s housing portfolio, which was almost nonexistent before 2020. In insurance, the SheforShield: Insure Women to Better Protect All report (IFC, AXA, and Accenture 2015) helped define the opportunity for targeting the women’s segment of insurance markets, which opened the doors to engaging with insurance companies on gender. By contrast, the operationalization of knowledge produced mixed results. After 10 years of support, the transition into investments is yet to materialize. The challenge is that developing the business case, building client demand, and establishing new insurance markets for women is time- and resource-intensive, particularly in cases where limited evidence is available to highlight women as a profitable market segment.

The reasons the World Bank and IFC have not been successful in operationalizing the knowledge they produce are manifold, with the first being weak internal and external dissemination of knowledge and guidance. The World Bank’s comparative advantage in producing robust knowledge is widely recognized not only by implementing partners but also by other development partners and CSOs. However, the dissemination of knowledge is weak, with the possible exception of Country Gender Assessments. Specific knowledge products are frequently not known externally or even internally. Although the FY16–23 gender strategy highlights the role of guidance as a key instrument to support knowledge operationalization (World Bank Group 2015), guidance is insufficiently disseminated and used. Within the World Bank, staff frequently do not know the available gender resources. For example, 53 percent of World Bank respondents to the IEG online survey (almost all TTLs or team members of gender-relevant projects) do not know what the follow-up guidance of the FY16–23 gender strategy of their GP is, or they know it exists, but they do not know the content. Similarly, 56 percent of World Bank and IFC respondents working in country offices do not know the resource package for the Bank Group country team, or they know it exists, but they do not know the content. Otherwise, most IFC survey respondents are familiar with the IFC FY16–23 gender strategy implementation plan and the IFC gender flag guidance. IFC key informants stress that industry and investment staff outside of financial markets are frequently unaware of gender knowledge produced and that more has to be done on market development and outreach outside of the institution.

The second reason for the Bank Group not being able to operationalize knowledge is that it is not always tailored to operational needs. Impact evaluations, which play a key role in the FY16–23 gender strategy theory of action, have been useful to assess the effectiveness of specific interventions and present a strong business case for gender equality to implementing partners and clients. At the same time, impact evaluations focus only on specific aspects of the theory of change. They cannot inform on how the sometimes complex interactions of the various project components work and cannot provide guidance on how the theory of change operates in specific contexts and conditions. This is, however, the type of guidance required to support replicability in different contexts. Several key informants of case studies stress that they lack specific knowledge to adapt lessons learned from analytic work to their specific context and target group and effectively implement the related interventions.

Finally, transferring knowledge to operations requires dedicated gender experts with sector- and context-specific expertise. According to many key informants, gender platforms and other gender coordination mechanisms—where they exist—facilitate knowledge uptake by operational teams and collaboration between gender experts and operational teams. In Bangladesh, the gender platform played a key role in connecting operational teams with the South Asia GIL, which provided systematic review of evidence and access to external knowledge. In Mexico, a peer learning platform enabled IFC advisory services to share and disseminate good practices from case studies at the corporate level. Some gaps remain, however, as the high quality of knowledge produced by the Bank Group does not necessarily translate into project design of corresponding quality.

- The World Bank Group’s approach to country engagement is country driven if, when preparing a Country Partnership Framework (CPF), the Bank Group starts from the member country’s own vision of its development goals, which may be laid out in a poverty-focused national development strategy. In consultation with key stakeholders in the country, including private sector clients, the Bank Group works with the government to draw on the findings of the Systematic Country Diagnostic and the Bank Group’s comparative advantage to determine the CPF objectives. Once the objectives are established, the CPF lays out a selective and flexible program of engagement tailored to the country’s needs to support the achievement of those objectives (World Bank Group 2014). The Independent Evaluation Group’s Mid-Term Review states that “the [gender] strategy defines a country-driven approach as coherent alignment with CPF objectives among operations that are supported by policy dialogue and the diagnosis of gender gaps to achieve sustained outcomes” (World Bank 2021b, 21).

- The evaluation did not use the gender tag and the gender flag to identify gender-relevant projects for three reasons. First, assessing the gender tag is part of the evaluation. Second, the gender tag and the gender flag do not distinguish between different levels of gender relevance (see box 2.1). Third, the gender tag and the gender flag as currently defined did not exist before the adoption of the fiscal year (FY)16–23 gender strategy.

- The World Bank addresses gender inequalities in time use in different ways, including through the provision of gender-sensitive infrastructure (water facilities, transport, and electricity), childcare and older adult care services, and time-saving technology (for example, mills and water pumps) and, in some cases, through the engagement with men and boys for a redistribution of unpaid care and domestic work. It also supports data production (for example, time use surveys) to make gender inequalities in time use visible. The International Finance Corporation (IFC) focuses on the provision of childcare in the workplace.

- In the Arab Republic of Egypt and Mexico, for example, the recent stand-alone lending is a development policy operation.

- In 2023, the Gender and Economic Inclusion Group transitioned to an official department, which adds greater ability to push for gender equality, inclusion, and women’s economic empowerment across IFC.

- The FY16–23 gender strategy intended to promote a more strategic and selective approach to addressing gender inequalities because of the direction provided by the gender tag and the gender flag to reduce well-identified, specific gender gaps; promote the country-driven approach; and increase the focus on monitoring results. As stated in the gender strategy document, the intent was to raise “the bar on gender equality by focusing on how the Bank Group can move beyond mainstreaming to an approach that identifies outcomes and monitors results of Bank Group–supported interventions in client countries” (World Bank Group 2015, 6).

- Many gender focal points spoke of excessive time and resources spent helping project teams tag additional financing of parent projects that originally were not tagged—projects that were, in their words, “untaggable.”

- The gender flag was created in 2013, but the percentage of gender-flagged projects started to increase substantially after IFC set targets for advisory services in FY16.

- The Bank Group made policy and financial commitments in the 2018 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development and IFC capital packages. IFC has made four gender-related commitments for 2030 as part of the recent capital increase package: (i) 50 percent share for women among directors whom IFC nominates to boards of companies where it has a board seat, (ii) $2.6 billion in annual commitments to financial institutions specifically targeting women, (iii) quadrupling the amount of annual financing dedicated to women and women-led small and medium enterprises to $1.6 billion, and (iv) flagging IFC projects with gender components (as applicable) by 2020.

- Since 2012, IFC’s Banking on Women has provided advisory expertise and invested $8.6 billion across 268 financial institutions in 81 emerging market and developing economy countries to provide finance and business solutions to women and women-led enterprises.

- The FY24 target for investment projects was exceeded (49 percent) across almost all industries.

- This may not be the case for most maternal health projects, which are considered stand-alone by this evaluation, to align with what the FY16–23 gender strategy considers gender gaps. Most projects that aim to improve maternal health do not contribute to reducing gender inequalities; they just address a specific need of women.