The Development Effectiveness of the Use of Doing Business Indicators

Chapter 2 | The Relevance of Doing Business: Is It “Doing the Right Things”?

Highlights

Doing Business’s (DB’s) ranking encourages competition among countries and motivates governments to consider reforms. DB has often been a first point of engagement of client countries in addressing legal and regulatory constraints to businesses.

Motivated by DB, many client countries have launched reform initiatives, with coordinating agencies leading the reform agenda. In several countries, those agencies have later pursued broader or deeper reforms not captured by the DB indicators (spillover effects).

Although DB rankings facilitate World Bank Group engagement related to the business environment, lack of granularity limits the indicators’ ability to monitor and evaluate reforms. DB indicators are perceived to be more useful for initial policy dialogue and engagement than as explicit objectives and monitoring tools.

DB indicators have serious limitations in capturing binding business environment constraints. The ability of specific individual indicators to reflect the specific business areas they cover is also limited.

The relevance of DB indicators can be constrained by unaddressed structural and institutional reform priorities, methodologies, and assumptions divorced from the reality faced by local small and medium enterprises.

DB indicators have notable inconsistencies with other Bank Group and global indicators.

DB is part of Bank Group efforts to produce reliable, relevant, and comparable data and analysis on private sector development. The ultimate objective is to promote job creation, economic productivity, and gender equality and to encourage and guide social and economic reforms promoting an efficient and fair business environment. Each year, the DB team within the Global Indicators Group of the DEC of the World Bank issues its annual flagship DB report. Claims to relevance (box 2.1)1 depend in part on the proven link of DB-inspired reforms to positive outcomes for private sector development, employment, productivity, and other beneficial outcomes examined in the next chapter on effectiveness.

Box 2.1. Views of World Bank Group Expert Practitioners

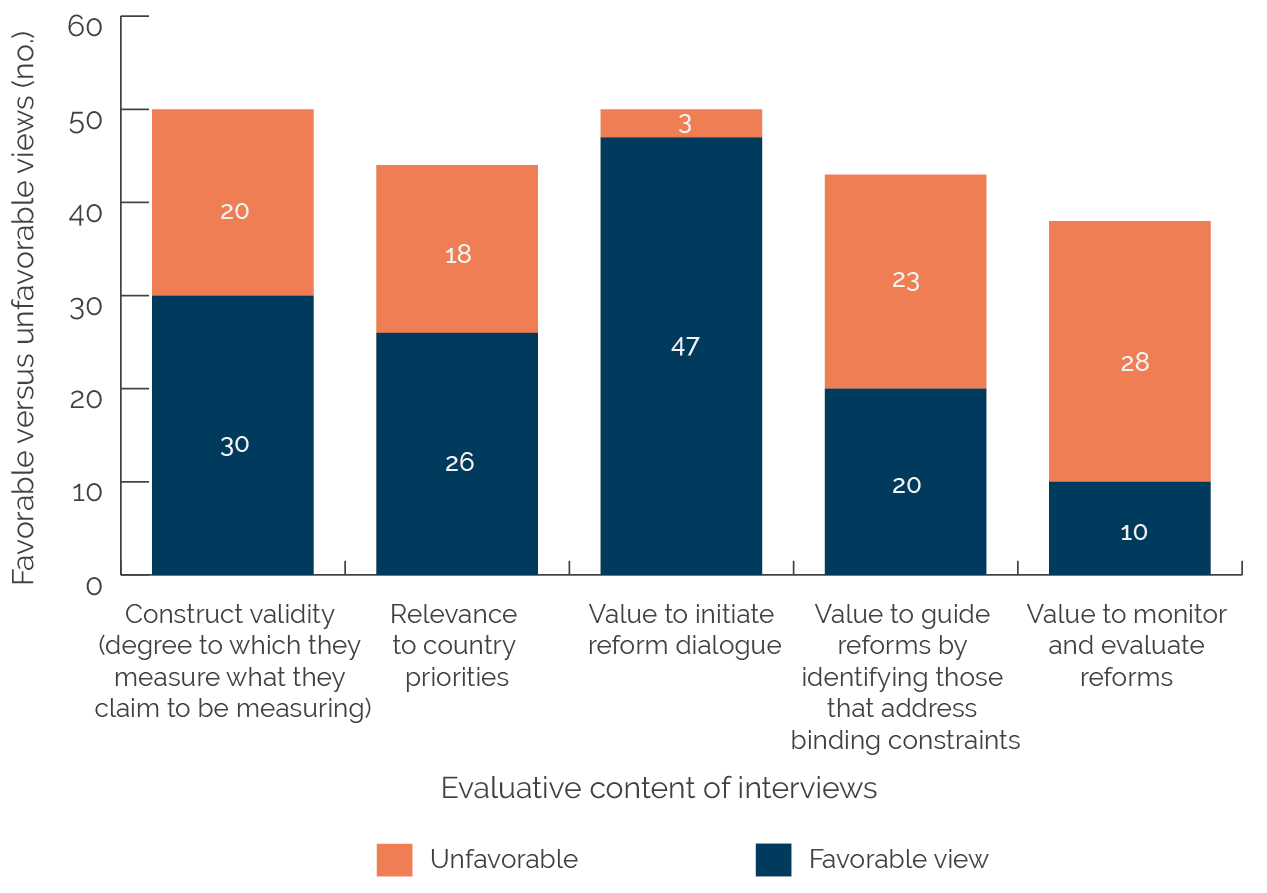

In IEG interviews with World Bank Group practitioners and managers, views expressed are overwhelmingly favorable with regard to the use of Doing Business (DB) to initiate dialogue and most views are positive as to DB’s relevance to country priorities (figure B2.1.1). 60 percent of views expressed in interviews identify indicators as validly measuring their business area, while 40 percent do not. Fewer than half of expressed views are favorable regarding DB as a guide for identifying binding constraints, and only 26 percent suggest DB indicators are a good way to monitor or evaluate reforms.

Figure B2.1.1. Experts’ Views of Doing Business Expressed in Semistructured Interviews

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: Interviews were performed with 20 World Bank Group expert practitioners.

Since 2003, DB has become a key resource for Bank Group work on the investment climate, for client country reforms, and for research. IEG’s review suggests the DB indicators have tracked thousands of reforms in client countries. In FY10–20, they were used to inform approximately 64 percent of Bank Group country strategies and were used in an estimated 676 projects with interventions worth $15.5 billion in commitments. They also informed a large number of research articles.

Client Country Reforms and Development Goals

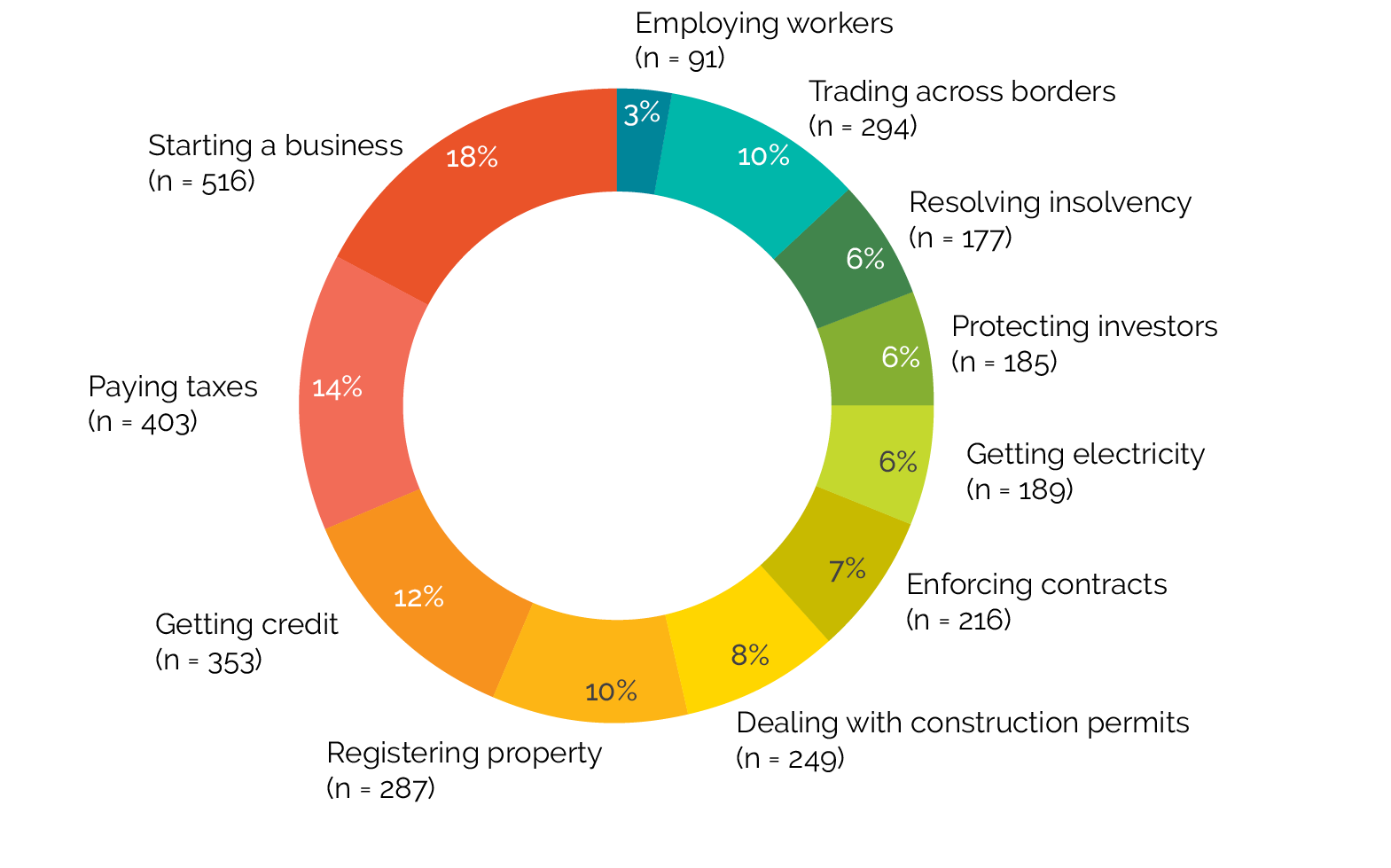

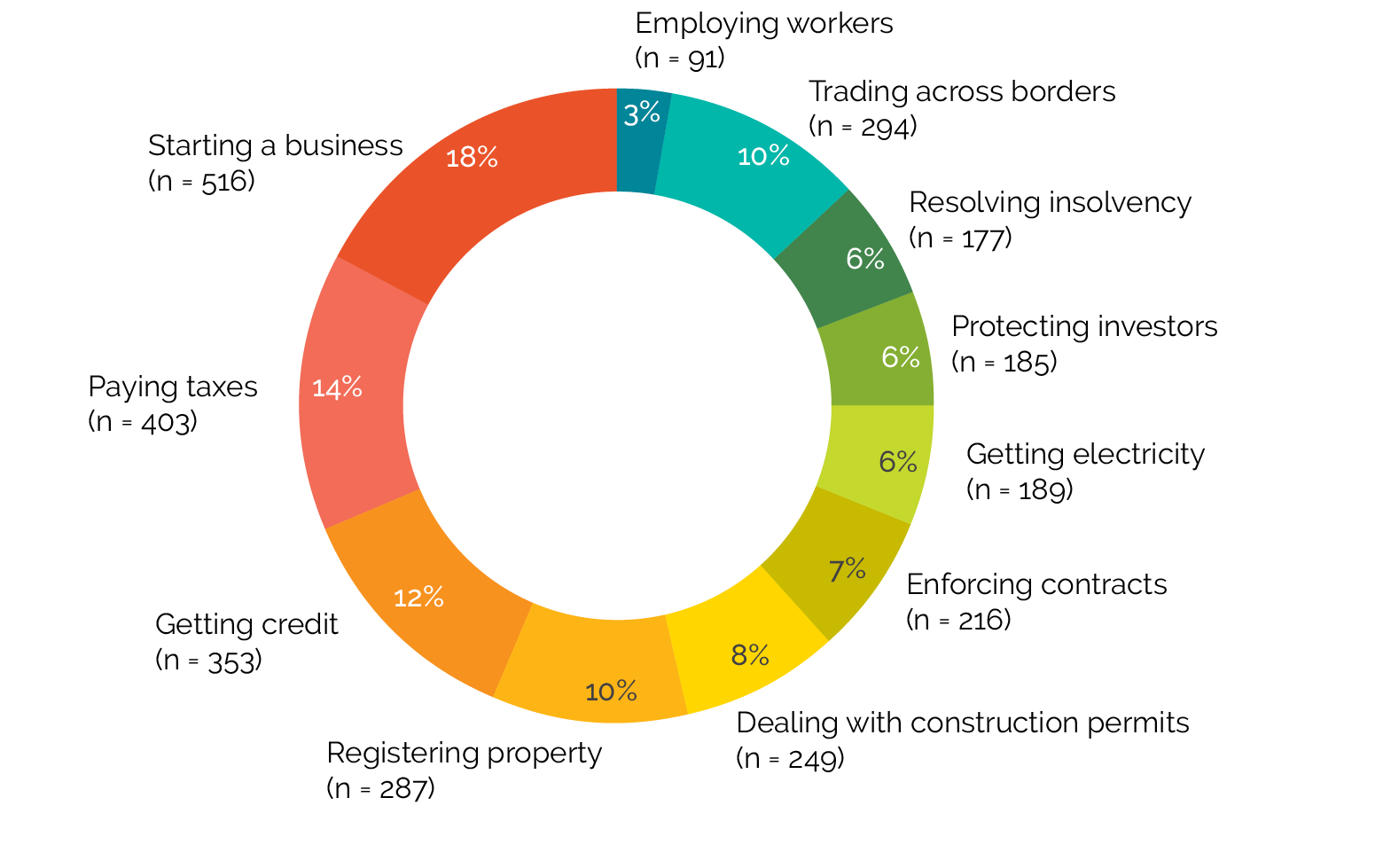

Client countries have made dedicated, substantial efforts to design and implement reforms measured by DB. Since 2010, DB has tracked 2,960 business regulatory positive, national reforms across 184 economies. Each year between 110 and 140 countries are reported to have introduced positive reforms. Among the most common have been reforms to starting a business, paying taxes, getting credit, registering property, and trading across borders (figure 2.1). Based on a 20 percent stratified random sample, the most popular types of reforms recorded have been improvements to business laws and regulations (23 percent), reengineering of processes (22 percent), automation or introduction of electronic systems (20 percent), reductions of fees or rates (16 percent), and establishment or reform of agencies (6 percent).

Although reforms across income levels were similar, upper-middle- and high-income countries were more likely to introduce electronic or automated systems, whereas low-income countries were more likely to improve laws or regulations or reengineer business regulation processes. For example, DB2018 documented that Kuwait introduced online business registration, while Mozambique reduced the time to get an electricity connection by consolidating procedures (World Bank 2017b). Fragility, conflict, and violence countries are also more likely to focus on improving laws or regulations, but they disproportionately focus on reducing fees and rates. For example, DB2019 reported that Papua New Guinea improved legal protection of minority investors, while Burundi, Myanmar, and Afghanistan reduced fees associated with starting a business (World Bank 2018b).

Figure 2.1. Positive National Reforms Tracked by DB2010–DB2020

Source: Doing Business reform database 2020.

Note: Includes only positive reforms, excludes subnational reforms.

DB has actively promoted competition among countries, celebrating “top reformers”—the countries achieving the largest number of measured reforms—up through the 2020 edition. Many countries have responded with initiatives to improve their ranking: Indonesia strives to be in the top 40 countries for “ease of doing business” (EoDB), Morocco to be in the top 50, and the Russian Federation to be in the top 20; Rwanda continually drives to be recognized among the top reformers. During the evaluation period (FY10–20; in declining frequency), Rwanda, Kazakhstan, Indonesia, the United Arab Emirates, India, Ukraine, Azerbaijan, Russia, Uzbekistan, Armenia, Brunei Darussalam, Kenya, and Morocco were credited with the highest total number of positive national reforms.

DB-informed targets and reforms feed into national development strategies and leadership initiatives. Rwanda’s first Economic Development and Poverty Reduction Strategy (2008–12; Rwanda Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning 2007) cites a specific DB indicator, and its second strategy (2013–18) cites a key accomplishment of the first plan: “the continued reforms in the Doing Business environment has laid the foundations for Rwanda to develop into a top investment and trade destination within Africa” (Rwanda 2013, 19). In May 2012, newly reelected Russian president Vladimir Putin approved the so-called “May decrees,” ordering government to increase Russia’s ranking in the World Bank’s EoDB index from 120th place in 2011 to 50th place in 2015 and 20th place in 2018 (Presidential Decree No. 596). In Indonesia, DB strongly influenced national development planning, with President Joko Widodo in 2017 affirming his intention for Indonesia to jump to 40th place in the EoDB ranking and instructing ministries to draft detailed plans to achieve it. India and Morocco both set explicit targets to be among the top 50 countries (by EoDB rank) in the world.

DB has been a first point of engagement with business environment reform for multiple countries, with reforms of legal and regulatory aspects of their business environments. IEG’s 2016 report on transformational engagements found DB to be transformational in ways other business environment diagnostics, including enterprise surveys, were not, in part because “it catalyzed actions to address constraints” (World Bank 2016d, 22). It found that “[e]ngagements with clients through the global Doing Business appear to have found traction with clients far more frequently than country engagements through [survey-based investment climate assessments]” (22). Interviews with Bank Group expert practitioners and managers suggest this is the area where DB indicators have the greatest value—“opening the door.”

Even some countries initially critical of DB, such as India, China, or Morocco, have over time embraced its approach and agenda. Typically, a low ranking in the overall EoDB index or in individual indicators can capture the attention of government leadership and stimulate a request to the Bank Group for an engagement, often beginning with a DB reform memorandum (box 2.2) or matrix.2 The memo lays out an agenda of changes to laws, regulations, procedures, and institutions that would improve a country’s DB score in specific indicator areas. Of 10 case study countries covered in this evaluation, 8 had DB reform memos prepared and others had a reform matrix.

Box 2.2. Doing Business Reform Memorandums

The Independent Evaluation Group reviewed 10 Doing Business (DB) reform memorandums (appendix C, addendum) delivered to governments for countries featured in the Independent Evaluation Group’s case or desk studies. Although the memos contained many useful, practical recommendations and tools to help improve DB indicator scores, the recommendations rarely drew from other sources or frameworks. They therefore risked missing overall challenges in each country’s business environment and even within each DB area of focus. In multiple cases, the best practice examples used were not tailored to the recipient’s stage of development or capacity.

Source: Independent Evaluation Group, review of 10 Doing Business reform memorandums..

Even in countries with small portfolios of DB-informed Bank Group operations, interaction with the Bank Group can lead to reforms. For example, both the United Arab Emirates and Russia, two countries with limited Bank Group DB-informed portfolios but a high level of reform activity, benefited from DB reform memos. The reform memo is often followed by technical assistance or financing support from the Bank Group, sometimes from other donors, and sometimes (especially for wealthier countries) from the government itself. The United Arab Emirates and Russia were both clients of World Bank reimbursable advisory services. Several governments also hired private consultants to support reform design and implementation efforts; high-income countries may use existing capacity.

The dual role of the Bank Group as generator of indicators and supporter of reforms to improve indicators has raised questions of a conflict of interest. IEG did not find this to be a common perception of clients and stakeholders (box 2.3).

Box 2.3. The Perception of World Bank Group Conflict of Interest between Indicator Generation and Operational Work

A recurrent theme emerging from Independent Evaluation Group (IEG) interviews with World Bank Group experts and operational staff was a concern about conflict of interest. Clearly, the recent suspension of Doing Business and new safeguards agreed to after a Group Internal Audit Vice Presidency audit reflect concerns that the interest in generating operations or pleasing clients has the potential to conflict with the interest in generating impartial data. A general perception of conflict of interest could challenge the credibility of the indicators or pose reputational risk to the Bank Group.

Although concern for or perception of conflict of interest was reflected in multiple Bank Group interviews, IEG did not encounter it in interviewing country counterparts and stakeholders for its case studies, even in response to explicit questions on the topic. (It is not clear whether the virtual online interview format affects interviewees’ candor or perception of confidentiality.) Several clients were clearly motivated to seek engagement with the Bank Group by a perception that the Bank Group knew how to improve their DB scores. In countries with reimbursable advisory services, there was an implicit potential for clients to “pull the plug” on financing if indicators did not move as intended. Yet, although the potential for conflict of interest is real, IEG did not find it to negatively influence client and stakeholder perceptions of the reputation of the Bank Group.

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

In most cases, governments create or empower coordinating agencies explicitly focused on the DB reform agenda. Typically, such agencies use DB indicators to help elaborate an initial agenda, to set explicit targets, to spur coordination and consultation, and to monitor and then publicize progress. In Morocco, for example, CNEA (Comité National de l’Environnement des Affaires; National Business Environment Committee) was formed in late 2010 as a specialized coordinating agency reporting to the prime minister. CNEA used DB indicators as a focus for reforms, to initiate areas of reform, as a clear basis to coordinate activities of diverse agencies, as metrics and monitoring indicators for reform, as the subject of public-private dialogue, and as a way to communicate to foreign investors and donors Morocco’s reform success. In Rwanda, a DB unit within the Rwanda Development Board (established in 2008) prepared an action plan on a yearly basis to be approved by a National Business Steering Committee. The unit designed and monitored DB-related reforms, managed development funds, organized working groups, advised agencies, and communicated with the private sector. The steering committee oversaw implementation of reforms at the cabinet level, coordinating relevant ministries and institutions. In addition, a Parliament Economic Committee reviewed DB-related laws and could fast-track priority measures. By contrast, in 2017, Chinese authorities used the powerful Ministry of Finance to coordinate reforms both nationally and in Beijing and Shanghai (box 2.4).

Box 2.4. Doing Business Reform: Traction in China

The Doing Business (DB) indicators found strong traction in China from 2017 onward. Beyond the interest in achieving rank improvement, a deeper appreciation grew of DB’s value as a diagnostic and benchmarking tool that would help cities in China assess their own performance and identify areas for change. The Ministry of Finance mobilized staff at the highest levels in Beijing and Shanghai, and city-wide reform plans were formulated using DB reform recommendations. The civil service developed a detailed knowledge of the indicators and their limitations. Both the International Finance Corporation and World Bank engaged in supporting reforms. The International Finance Corporation began early, through access to finance work greatly enhancing credit information. World Bank reimbursable advisory services (RAS) supported work on the insolvency framework. Another RAS project focused on Shanghai, seeking to improve construction permitting and trading across borders, while a Beijing-focused RAS project supported reform of construction permitting and property registration. The National Development and Reform Commission began exploring possible Chinese indicators and application outside the principal cities. Relevant areas were identified but use of formal indicators was not yet evident at the time of the case study.

Source: Independent Evaluation Group

In many countries, the agencies and capacities created or empowered to pursue DB reforms later turn to a broader or deeper agenda of business environment reform, creating a “spillover effect.” Given DB’s strong role observed as a “door opener” for reform activities, it is not surprising that the open door can lead to reforms not captured by the DB indicators. Such spillover benefits can occur through a deepening of reforms within legal and regulatory areas covered by DB, a broadening of reforms to other aspects of the business environment, or a geographic broadening of DB reforms subnationally to cities or localities not captured in the DB indicators. Clearly, where there are limits to DB’s approach to identifying reform priorities or guiding and measuring reforms, such spillovers may not be entirely positive.

Although countries are often motivated by DB, other analytic tools, indicators, and expertise are often mobilized to guide and deepen reforms. Eight of IEG’s 10 case studies explicitly identified the use of such augmentation (box 2.5). Sometimes other indicators—such as enterprise surveys, the World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Report indicators, or the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development regulatory indicators—were used, but often frameworks and tools specific to a reform area (such as the Tax Administration Diagnostic Assessment Tool) were applied. IEG’s review of IFC AS projects notes that teams often find DB indicators ill-suited to guide and monitor projects, and in many cases, teams conducted their own diagnostic surveys or used other tools to generate more specific and tailored guidance and benchmarks. Bank Group projects on secured transactions (covered by “getting credit”) often draw on the 2007 United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL) legislative guide on secured transactions, the 2016 UNCITRAL Model Law, the United Nations Convention on Assignments of Receivables Accounts, in Internal Trade, or the Insolvency and Creditor Rights Standard developed by the World Bank and UNCITRAL.

The reform momentum and capacity instigated by DB are often applied to additional topics. In Morocco, the CNEA in recent years has added new issues to its agenda, applying both the coordinative capacity and indicators-based reform approach to additional areas and to subnational governments not included in the first round of reforms. Under its reform process, Indonesia approved its Omnibus Law modifying over 70 laws linked to easing the policy burden on business, extending well beyond what was covered by the DB indicators alone.3 In 2019, Indonesia’s head of the Ministry of National Development Planning announced a transition to e-bureaucracy to support the ease of doing business, again extending beyond measures explicitly captured by the indicators. Not all countries show such spillover benefits—for example, in Afghanistan, the agenda remained focused on DB.

Box 2.5. Colombia: Broadening the Evidence Base for Reform, Fiscal Years 2010–20

Colombia’s regulatory reform objectives were informed by Doing Business (DB) and complemented by other analytical work. DB’s scope was too narrow to identify reform priorities by itself and was used in combination with other tools and sources of data. The government of Colombia regularly monitors three indicator reports along with sector-specific data and research: Doing Business, the World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Report, and the International Institute for Management Development’s World Competitiveness Yearbook. Colombia used DB data as supporting evidence for its business environment diagnoses and, in some cases, to point to areas in need of reform. To complement DB data, the government of Colombia closely monitors the World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Report series, referencing the reports in national development plans and utilizing their insights related to the government of Colombia’s overall competitiveness strategy beyond legal and regulatory aspects. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development has also been a trusted adviser, providing information on best practices and benchmark data on both general competitiveness and productivity issues and on regulatory reform. It closely advised Colombia’s reforms to the regulatory process and produced regulatory reviews in the context of Colombia’s accession to Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. The World Bank’s own support to reform through development policy loans and advisory services was based in broader analysis than DB, reflected in policy notes, working papers, and the Systematic Country Diagnostic.

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

National-level reforms, although often initially pursued in one or two leading cities captured by DB, are frequently extended to subnational levels. India developed its own subnational indicator system inspired by DB to encourage and reward reform competition among its states to make it easier and quicker for businesses to operate. From 2014, the government of India introduced the Business Reform Action Plan, overseen by the Department of Industrial Policy and Promotion. The Russian government developed key performance indicators inspired by DB, then introduced a subnational program of key performance indicators to encourage virtuous competition among provincial governors. The program was coordinated by a national nongovernmental organization, the Agency for Strategic Initiatives, which also generated standards to guide regional policy makers on how to improve the regional business environment and attract investment. In Morocco, the measured progress of DB reforms at the national level, combined with a national strategy of decentralization, spawned support for subnational indicators and reforms extending to the Marrakesh region and beyond.

Several country case studies revealed serious limitations to the DB indicators and agenda in capturing business environment reform priorities. In no case study did IEG find that the problem areas identified by DB were directly inconsistent with national development plans and objectives, but in many cases, they were not development priorities. In the cases of fragility, conflict, and violence countries, such as Afghanistan and the Democratic Republic of Congo, political stability and risk of conflict weighed heavily on businesses and constrained any potential supply response to regulatory reforms. In many other countries, including Morocco and Jordan, the lack of a level playing field for domestic SMEs meant that DB failed to capture the substantial disadvantages imposed on SMEs through advantages granted to favored foreign or domestic investors through tax advantages, access to special economic zones, preferential access to land or credit, or explicit subsidies. In several countries, state ownership also limited private sector opportunity in multiple sectors. In multiple countries, the presence of corruption, large informal sectors, or state capture weakened the relevance of DB indicators to binding business constraints. For example, in one country, despite a thorough streamlining of dealing with construction permits (DWCP), businesses reported that, at the end of the process, approval still required a meeting with an official who expected a bribe.

The relevance of the DB agenda is weaker in countries where structural or institutional factors act as binding constraints. For example, Rwanda could not address the disadvantages of being small or landlocked through DB reforms. Further, its 2019 CPSD pointed to a host of binding constraints more pressing than the DB agenda, including low skills (human capital), limited access to and high cost of energy, high transport and information and communication technology costs, restricted access to land, and an unlevel playing field for competition. In India, critical aspects of binding constraints cited by stakeholders or revealed in enterprise surveys lay outside the DB agenda, ranging from weak infrastructure to land and labor constraints. In Jordan, key constraints included massive unemployment and poverty, as well as income disparity and gender inequality. In China, a host of issues ranging from inefficient bureaucracy to bank debt figured among leading constraints cited by stakeholders and experts interviewed but mostly missed by the DB agenda.

In some countries, it is not clear whether the domestic SME focus of the DB agenda was the real focus of the reform efforts. In Jordan and Afghanistan, the reforms were being pursued largely with an audience of donors and potential foreign investors in mind. With some indicators, like protecting minority investors, it is not clear how well the base case assumptions map to the typical domestic SME, although the indicator may well resonate with a foreign investor. Rwanda pursued an improved external reputation to attract foreign investment, in part through the publicity of being a recurrent top reformer. Russia sought to burnish its international image while also aiming to improve the domestic business environment. Although appealing to additional audiences—whether domestic voters, foreign donors, or international investors—may be considered a benefit of DB reforms, it can also inspire strategic behavior, pursuing reforms that move indicators without yielding tangible benefits to domestic SMEs. How client countries use the indicators depends on their motivation and their capacity.

Over time, the DB agenda can lose its relevance for several reasons, when (i) non-DB constraints become binding after early DB reforms, (ii) pending DB reforms prove less tractable, and (iii) a DB indicator does not adapt to changes in the underlying business process or technology. First, over time, active reformers may have addressed the most pressing constraints measured by DB and move on to other policy priorities. This may explain why top 10 EoDB countries like New Zealand, Denmark, and the United States show a rate of one or fewer reforms per year from FY10 to FY20. Second, within each policy area, as the more tractable areas are addressed, the remaining DB agenda may rest with longer-term or politically more difficult reforms. India, like many other countries, progressed first on relatively easy procedural simplification in starting a business, paying taxes, trading across borders, and DWCP, which reduced the time and the costs involved. Reforms in more difficult areas involve legal processes, such as resolving insolvency, registering property, and enforcing contracts. Indicative of the long-term nature of these challenges, despite important reforms to improve its insolvency framework, business associations reported the persistence of slow, cumbersome, and inefficient resolution in court. Despite serious effort to improve its insolvency framework, business associations reported the persistence of slow, cumbersome, and inefficient resolution in court. Third, where DB indicators are not adapted, the reform agenda may shift away from them as the underlying technology or nature of the business area evolves. For example, progress in e-government may invalidate traditional measurements of number of procedures or assumptions about the time taken by each step in such contexts as starting a business and paying taxes. In getting credit, advances in use of big data and the emergence of digital financial services can reduce the relevance of existing credit information indicators.

Business Area Relevance of Doing Business Indicators

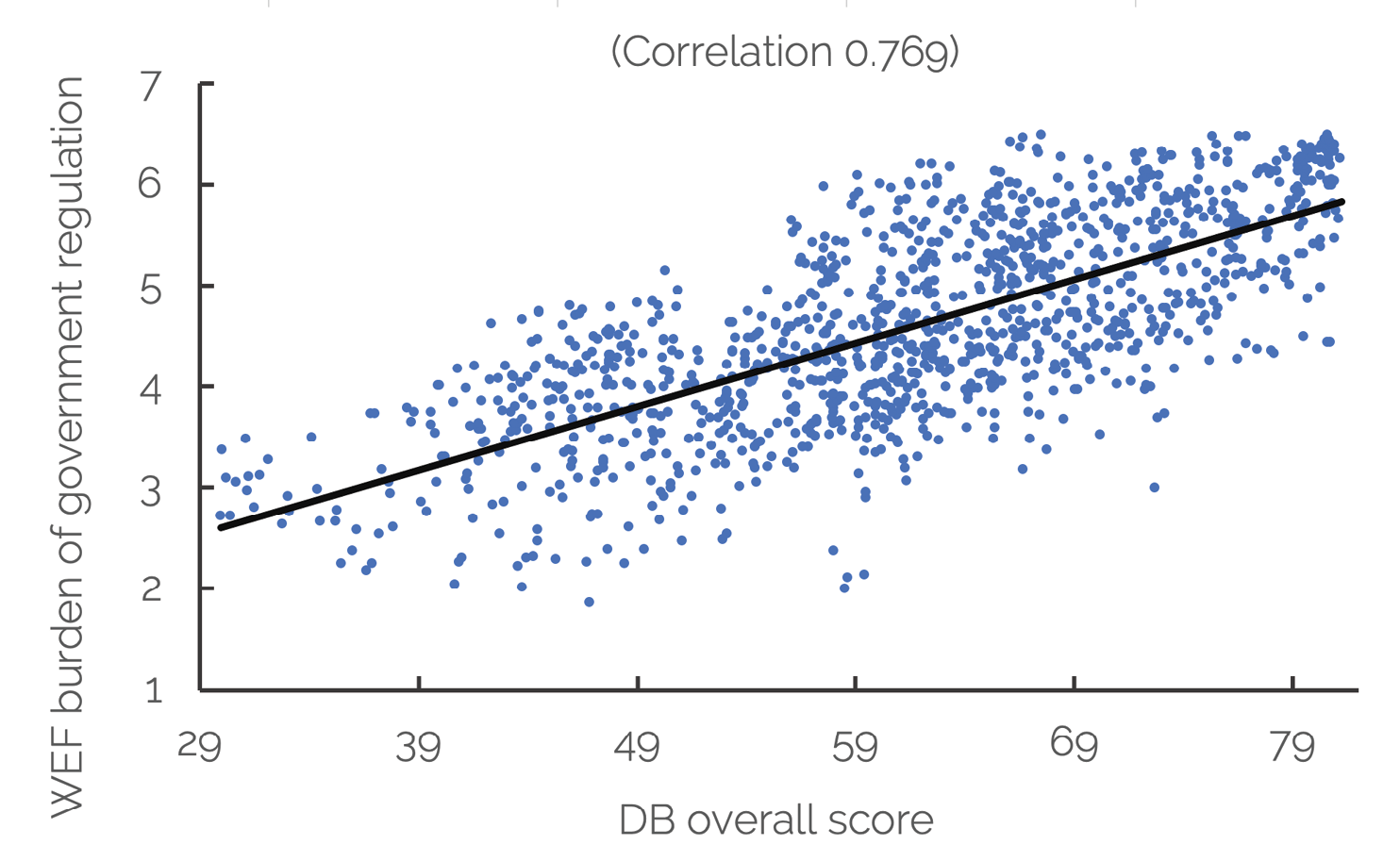

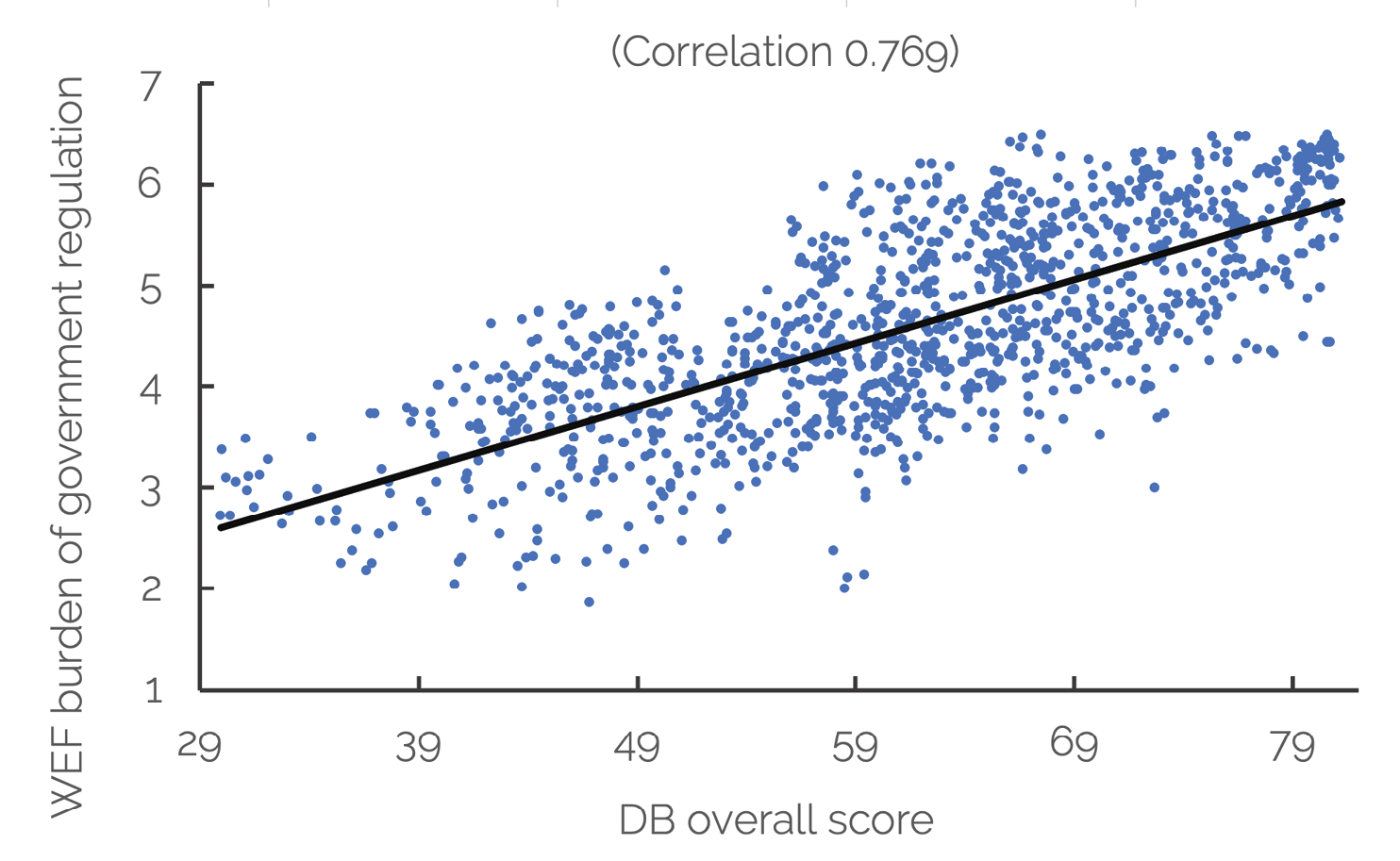

The overall EoDB score serves as a general index of the overall regulatory environment. A low EoDB score corresponds generally to other indicators of administrative burden or weak regulatory quality. For example, statistical analysis shows a high correlation (77 percent) between the EoDB score and the World Economic Forum’s survey-based indicator of the burden of public administrative requirements perceived by business managers (figure 2.2).

The ordering of reform priorities using DB indicators and business enterprise surveys shows some alignment. Within the areas DB measures, IEG considered statistical evidence comparing the ordering of priorities indicated by DB scores to the ordering of priorities indicated by businesses responses to enterprise surveys. The IEG analysis matched four overlapping categories between DB and enterprise survey responses by country and year, namely tax administration, trade regulations, access to electricity, and access to finance. Based on 95 observations, the analysis found a perfect match in the ordering of priorities in 28 percent of cases, a close match (with only one single position difference in rank) in 41 percent of cases, and a mismatch of rankings in the remaining 31 percent of ratings. Differences in methodology and among the firms sampled in surveys versus those described in the DB base case assumptions may explain some of this deviation, but it points to the value of using multiple sources of evidence to guide reform priorities.

Figure 2.2. Correlation between the Doing Business Ease of Doing Business Overall Score and the World Economic Forum Burden of Regulation Indicator

Source: Independent Evaluation Group, statistical analysis of Doing Business indicators.

Note: DB = Doing Business; WEF = World Economic Forum.

DB indicators do not capture well the real conditions experienced by businesses within each area covered by an indicator.4 IEG notes a low correlation between DB scores and how firms operating within countries report their experience. Regarding the DWCP indicator, there is only a 23 percent correlation between the DB measure of time to get a construction permit and the experience reported by firms in surveys. For the getting an electricity connection indicator, this correlation is only 10 percent. For both indicators, the DB indicators tend to overestimate time compared with actual firm experience. Regarding the time to import indicator, there is only a 42 percent correlation with firm experiences reported in surveys despite improved methodology since DB2016, an underestimate. Regarding the time to export indicator, the correlation of DB to enterprise survey responses is 35 percent, with DB again underestimating relative to survey responses.

Table 2.1. Correlations and Over- or Underestimating DB versus Enterprise Surveys

|

DB Indicator |

Corresponding ES Indicator |

Correlation Coefficient (%) |

Over or Underestimate |

|

Time to get a construction permit |

Time to get a construction permit |

23 |

Overestimate |

|

Time to import (DB16–20 methodology) |

Time to import |

42 |

Underestimate |

|

Time to export (DB16–20 methodology) |

Time to export |

35 |

Underestimate |

|

Time to import (DB06–15 methodology) |

Time to import |

25 |

Overestimate |

|

Time to export (DB06–15 methodology) |

Time to export |

23 |

Overestimate |

|

Days to get electricity connection |

Days to obtain electrical connection |

10 |

Overestimate |

Source: Independent Evaluation Group, statistical analysis of DB and enterprise survey data.

Note: DB = Doing Business; ES = enterprise survey, various years–DB data matched to timing of enterprise surveys..

Within each indicator area, there are limitations to how the indicator applies to conditions faced by businesses in the field.5 IEG conducted five deep dive studies to review the most reformed indicator areas. They show strengths and limitations of the relevance of each indicator set to the business area it covers. The dives considered information from several sources: two literature reviews, a portfolio review, country case studies, and interviews with experts and practitioners. The latter give DB substantial credit for drawing attention to administrative burdens on firms and launching discussions about its individual policy areas.

Limitations in DB indicators are generally attributed to shortcomings in their defined topical coverage and in the representativeness of the base case scenario.6 Given its challenging task of collecting data for 190 countries every year, DB has stylized or simplified its coverage of certain areas. This involves the use of base case scenarios, intended to enhance comparability between countries, and coverage of only one or two cities. The reliance on intermediaries (for example, lawyers, accountants, freight forwarders) greatly streamlines data collection relative to surveys. Yet these measures can constrain the representativeness of reported data.

Lack of substantive coverage can limit the extent to which the indicators can (or should) guide reforms or reflect reform progress. DB reports caution readers on a few of the limits to the indicators (box 2.6). One issue is the detail and granularity of indicators, which are by necessity simplified. DB can be a crude instrument for monitoring reform measures, often crediting reform on issuance of a law or regulation before implementation, or failing to recognize certain important reforms. Questions on granularity and comprehensiveness raise the concern that indicators as reform metrics can leave important things out in individual areas. For example, a World Bank expert on insolvency noted that, although the indicator had improved to cover 13 or 14 legal subindicators, clients really would need at least 25 to have the granularity needed for understanding and guidance on the issue.

The characteristics describing the DB base case scenario are not always consistent with those experienced by the typical domestic SME. To understand relevance issues more clearly, IEG conducted detailed “deep dives” to examine five DB indicators that were the most popular areas of reform. These deep dives found inconsistencies between specifications of the base case scenario and the typical domestic SME. One challenge is that the scenario behind some indicators describing a prototypical firm or transaction could not be the same one used for the scenarios underlying other indicators. For example, the firm for starting a business must not engage in international trade, so would never encounter a trading across borders situation. That same firm (with five partners) would not qualify for the scenario in protecting minority investors. The findings on relevance from these deep dives are summarized in table 2.2. More details can be found in appendix D.

Box 2.6. Caveats in Doing Business Reports, 2010–20

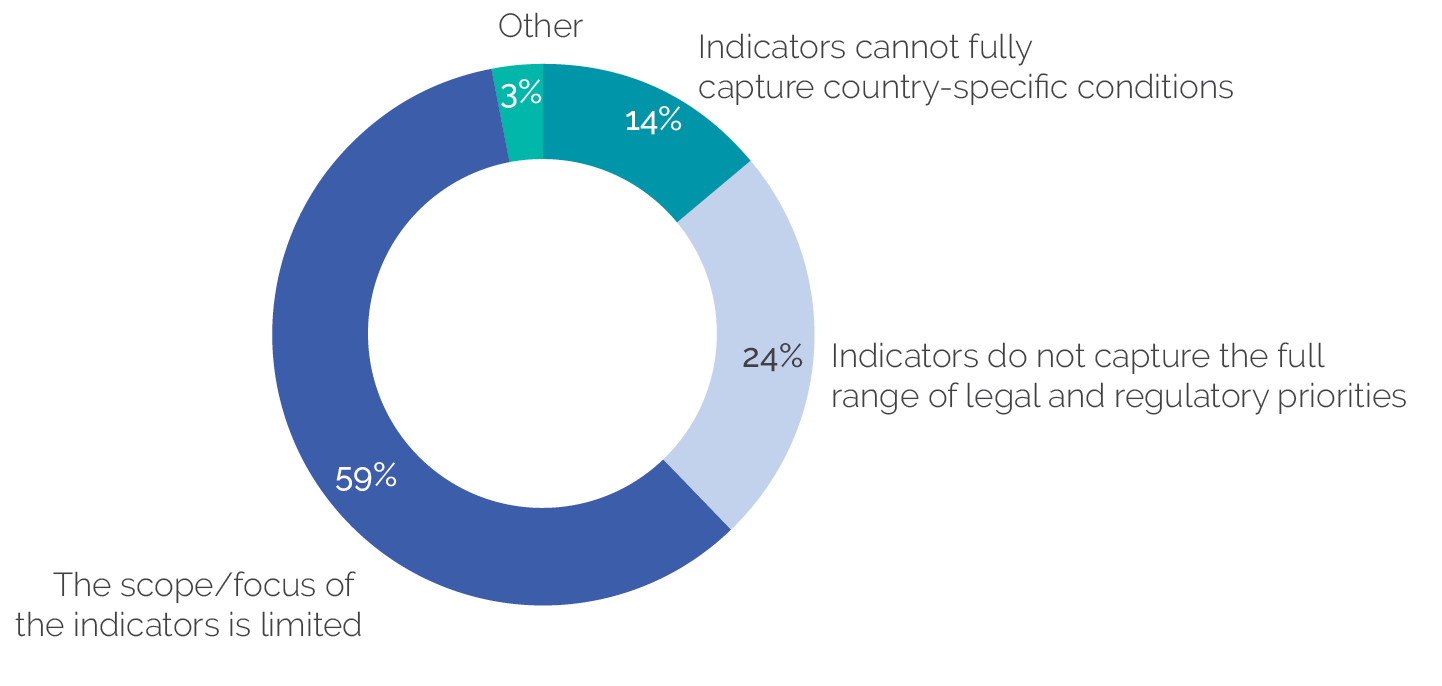

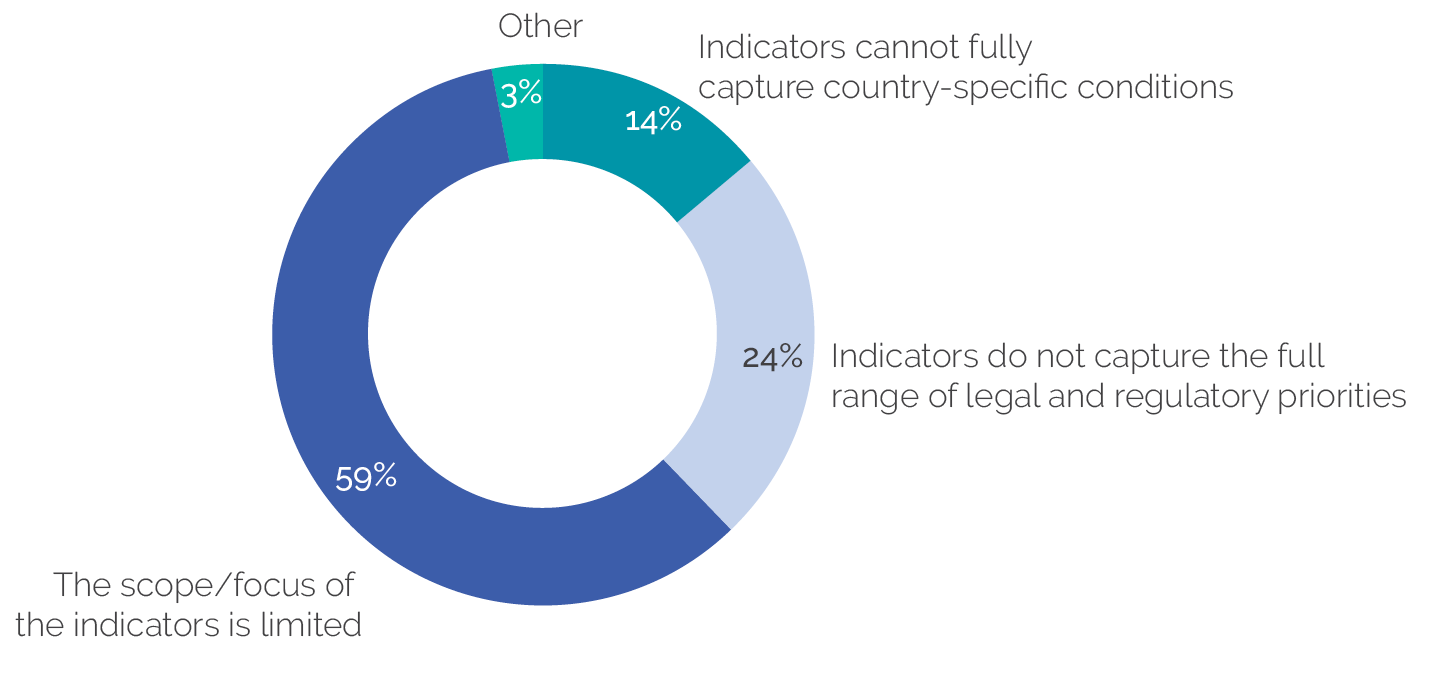

The Independent Evaluation Group found 87 caveats in Doing Business reports alerting readers about some limitations of the indicators. Three types dominated: the limited scope of the indicators, the limited extent to which indicators capture the full range of legal and regulatory priorities, and the limited ability of indicators to capture country-specific conditions (figure B2.6.1).

Figure B2.6.1. Caveats in Doing Business Reports

Source: Independent Evaluation Group, analysis of Doing Business 2010–20 reports (World Bank 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014a, 2015a, 2016c, 2017b, 2018b, 2019a), and supervised machine learning.

Table 2.2. Key Findings on Relevance from Doing Business Indicator Deep Dives

|

DB Indicator |

Summary Findings |

|

Starting a business |

|

|

Getting credit |

|

|

Trading across borders |

|

|

Dealing with construction permits |

|

|

Paying taxes |

|

Source: IEG Deep Dives – see appendix D..

Note: DB = Doing Business; VAT = value-added tax.

World Bank Group Country Strategy and Operations

The Bank Group uses DB in country strategies to identify reform needs and to motivate future operations in priority areas. Bank Group expert practitioners find near universal appreciation of the relevance and value of DB indicators to initiate reform dialogue. Most responses favored the relevance of the indicators to country priorities. Yet there was an almost even division of positive and negative responses on the value of the indicators to correctly identify binding constraints. And the preponderance of views weighed against the use of DB indicators to monitor and evaluate reforms.

Many World Bank country strategies make substantial references to DB or propose a DB-related work program or both. IEG examined 61 country strategy documents with corresponding IEG reviews and found that 64 percent of the strategies substantially referenced DB or proposed a DB-related work program. These strategies forecast planned interventions including improving business laws and regulations (38 percent), streamlining procedures (34 percent), using electronic or automated systems (15 percent), and conducting diagnostics (11 percent). Examples include policy development and regulatory streamlining in the Philippines (World Bank 2019d); policy dialogue and advice in Mexico (World Bank 2018d); and policy and project support in Rwanda (World Bank 2019c). The World Bank’s own assessment of the quality of countries’ policy and institutional frameworks uses DB indicators as inputs to inform its coverage of the business regulatory environment (starting a business, resolving insolvency, registering property, protecting minority investors [shareholder rights], and DWCP); nontariff trade measures (trading across borders); property rights (enforcing contracts); and efficiency of revenue mobilization (paying taxes).

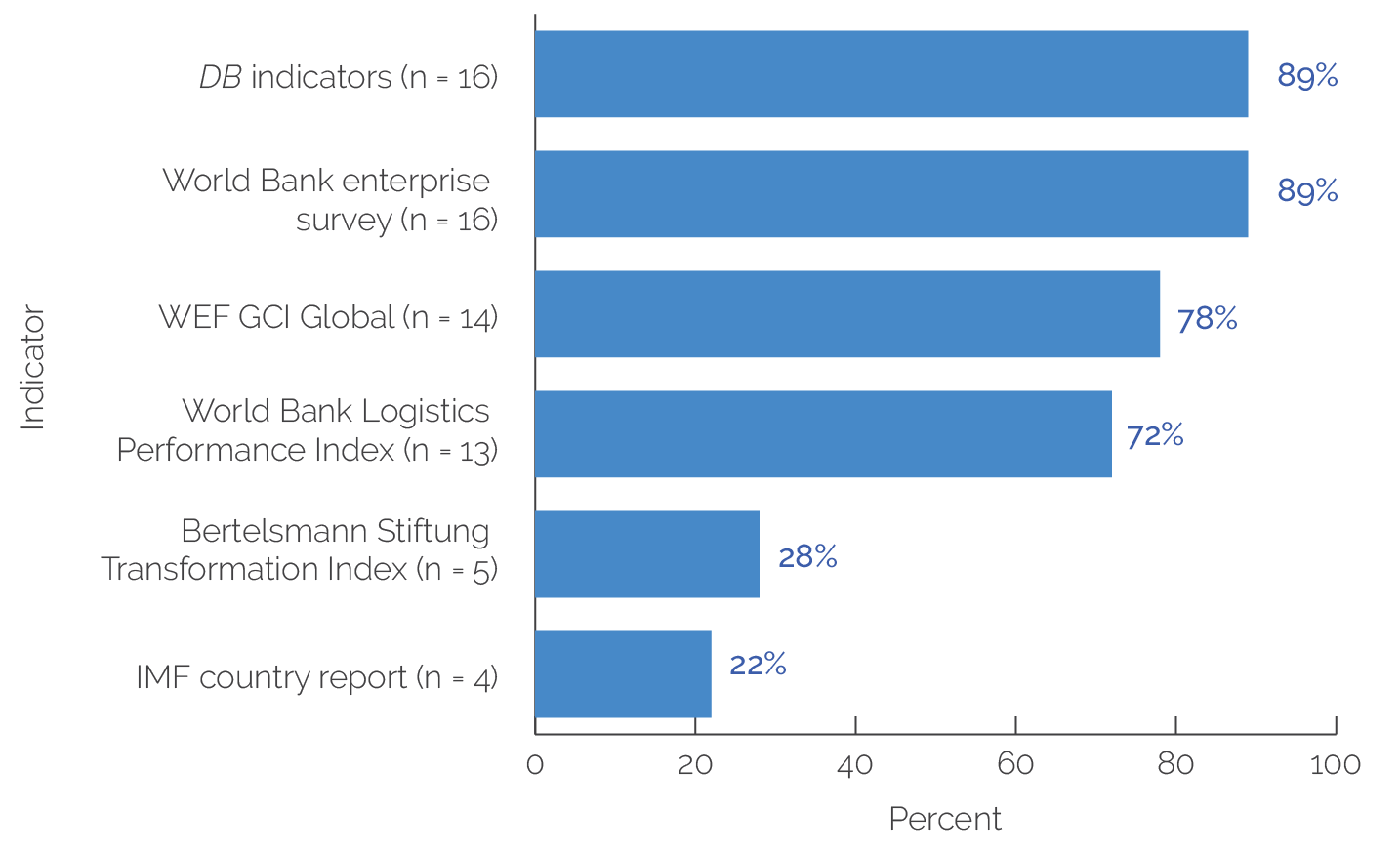

DB is the most popular source of business environment information but not the only one, even among Bank Group products. IEG reviewed 18 CPSDs, the Bank Group’s current comprehensive private sector development analytics produced jointly by IFC and the World Bank. It found that the CPSDs incorporate DB indicators as a leading input in a way that can be quite independent from and integrated with information from other Bank Group and global indicators and evidence sets (figure 2.3). IEG’s review of 50 evaluated IFC AS projects found that many use other primary indicators, including some standard AS indicators designed to produce data more focused on the scope, depth, and timing of the engagement, and more granular and aligned with project objectives.

Figure 2.3. Indicators Used as Measures of Business Environment Constraints in Country Private Sector Diagnostics

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: DB = Doing Business; GCI = Global Competitiveness Index; IMF = International Monetary Fund; WEF = World Economic Forum.

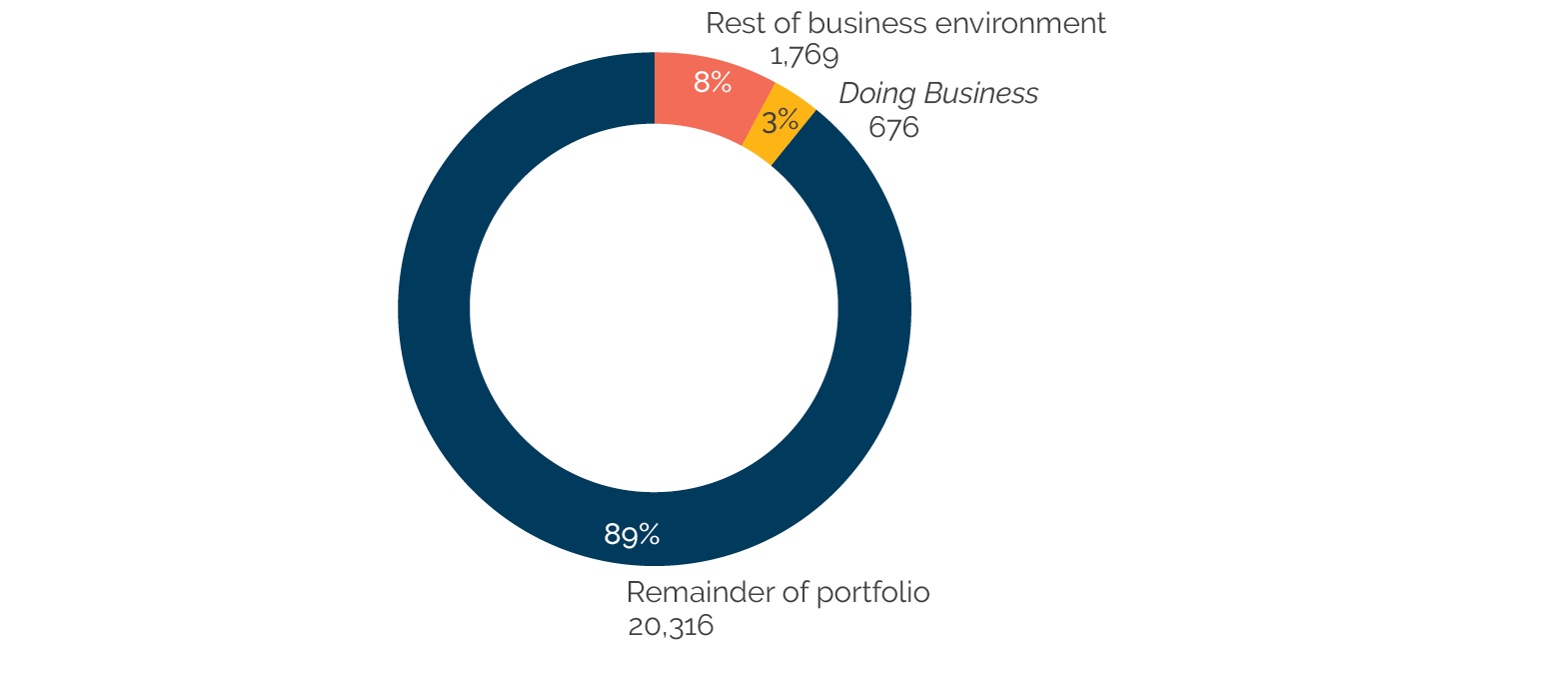

DB informs a substantial share of the Bank Group’s projects providing financing, advice, and technical assistance to client countries on the business environment. This DB-informed portfolio consists of 676 projects representing $15.5 billion in commitments during FY10–20 (table 2.3). It includes projects that (i) use DB in their Board documents to justify the project, or (ii) have one or more DB indicators in either their objectives, or (iii) have one or more DB indicators as monitoring indicators, or (iv) are intended specifically to inform DB indicators. The DB-informed portfolio constitutes approximately 28 percent of the 2,445 projects dealing with the business environment and approximately 3 percent of 22,761 Bank Group projects (figure 2.4).

Table 2.3. Summary of Doing Business–Informed Portfolio, Approved in Fiscal Years 2010–20 (projection)

|

Institution |

Projects |

Interventions |

Commitments |

|||

|

(no.) |

(%) |

(no.) |

(%) |

(US$, millions) |

(%) |

|

|

World Bank lending |

269 |

40 |

517 |

43 |

14,853 |

96 |

|

Subtotal |

269 |

40 |

517 |

43 |

14,853 |

96 |

|

World Bank ASA |

165 |

24 |

173 |

14 |

379 |

2 |

|

World Bank RAS |

58 |

9 |

81 |

7 |

20 |

0 |

|

IFC AS |

184 |

27 |

428 |

36 |

287 |

2 |

|

Subtotal |

407 |

60 |

682 |

57 |

686 |

4 |

|

Total |

676 |

100 |

1,199 |

100 |

15,539 |

100 |

Source: Independent Evaluation Group, portfolio review analysis assisted by supervised machine learning.

Note: Projected based on population and sample sizes. Volume/commitment/funds managed were identified or estimated according to what was allocated to Doing Business–related interventions. If not explicitly stated, it was estimated based on the number of components, subcomponents, or activities. Consultations with World Bank Group resulted in exclusion of some projects. ASA = advisory services and analytics; IFC AS = International Finance Corporation advisory services; RAS = reimbursable advisory services.

Figure 2.4. Share of Doing Business–Informed Projects in World Bank Group Portfolio, Fiscal Years 2010–20

Source: Independent Evaluation Group, portfolio review..

The World Bank provided lending support that is informed by DB to 97 countries, and the World Bank and IFC together provided advisory services and analytics informed by DB to 126 countries. In total, 136 countries were supported by DB-informed operations. By income level, 29 percent of projects were delivered to low-income countries, 38 percent to lower-middle-income countries, 25 percent to upper-middle-income countries, and 8 percent to high-income countries. Reimbursable advisory services figured prominently in services delivered to high- and upper-middle-income countries. Regionally, Sub-Saharan Africa was the region with the highest number of approved projects (34 percent), while Middle East and North Africa had the highest average in lending projects per country (4.5), and South Asia had the highest average per country in advisory projects (4.8). Regional projects, mostly in Sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America and the Caribbean, constituted 7 percent of the estimated portfolio.

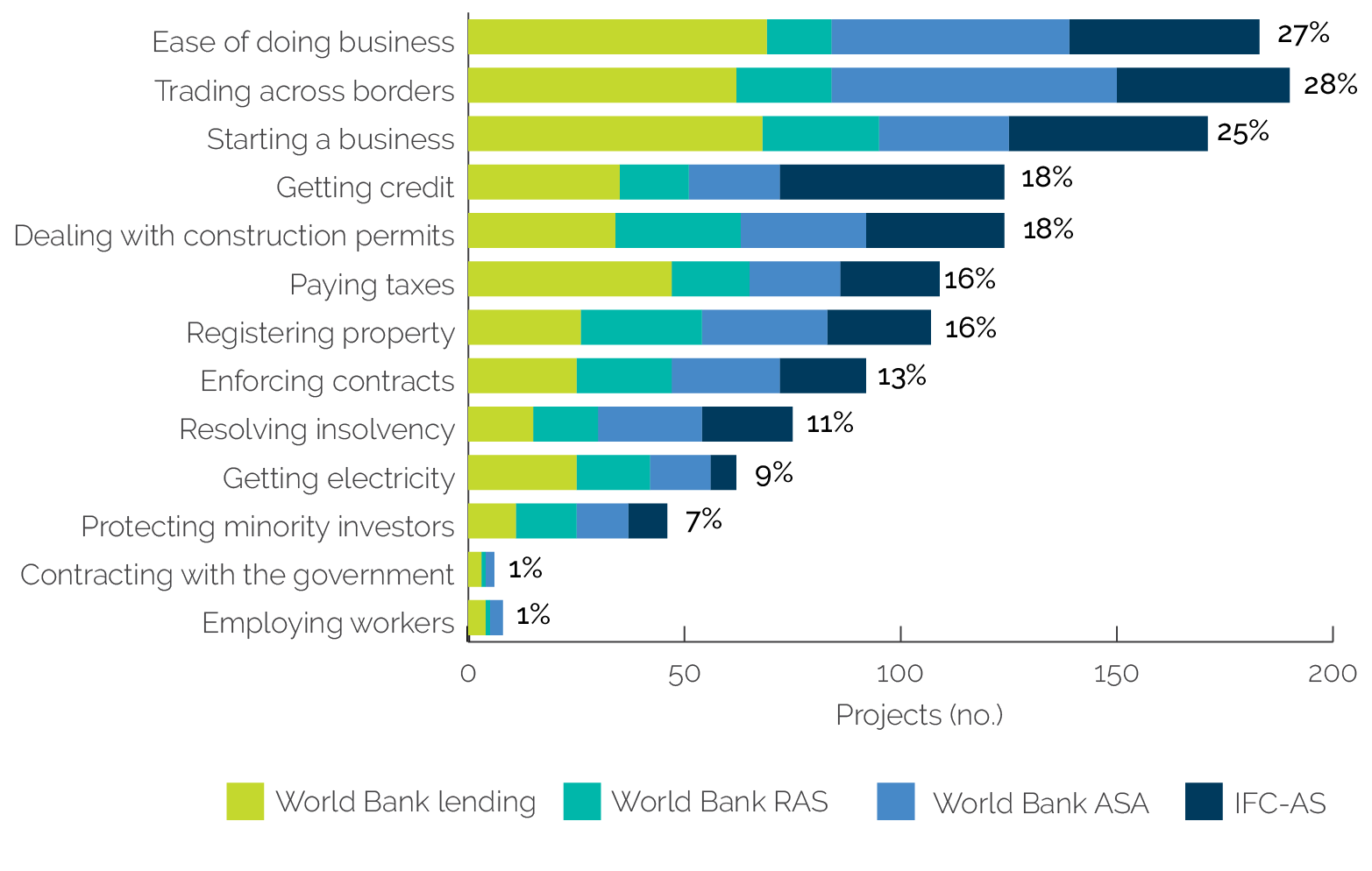

Within the DB-informed portfolio, besides general support to improve the EoDB (27 percent), the most popular reform interventions focused on a selection of business areas covered by the indicators. They include trading across borders (28 percent), starting a business (25 percent), getting credit (18 percent), and DWCP (18 percent), with paying taxes and registering property close behind (figure 2.5). Of the identified projects, 47 percent use DB indicators as justification, 29 percent use them to measure reform progress, and 15 percent use them in project objectives. Tanzania’s First Business Environment for Jobs development policy operation (FY16) exemplified DB indicators as objectives, aiming to reduce business start-up time from 26 to 10 days and procedures from 9 to 3 days.

Project objectives in the DB-informed portfolio focused most often on improving a law or regulation (27 percent), reengineering a process (16 percent), building capacity and training (15 percent), and conducting a diagnostic (13 percent). Turkey’s Second Restoring Equitable Growth and Employment Programmatic Development Policy Loan (P123073; FY11), for example, helped government to adopt a new commercial code enhancing protection of minority shareholders. The IFC AS Georgia Investment Climate Project (599537; FY14) assisted Georgia to streamline regulations and procedures (including through e-government) related to trade, enforcement of contracts, and insolvency. The IFC AS Afghanistan Business Enabling Project (602848; FY18) provided training and capacity building to Afghan agencies including peer-to-peer learning.

Figure 2.5. Projected Doing Business–Informed Portfolio FY10–20 by Indicator Area and World Bank Group Institution (number and percent of DB-informed projects)

Source: Independent Evaluation Group, portfolio review analysis.

Note: Projected based on population and sample sizes. Results were multiplied by a factor of 226/107 for World Bank lending projects, and 789/452 for World Bank ASA projects. Where a project or component specified an indicator it would work on, it was included under that indicator. Projects are counted more than once if supporting more than one business area. Projects with components that do not identify a specific indicator or that discuss reform in multiple indicator areas without a specific allocation of project resources to each were categorized as “ease of doing business.” ASA = advisory services and analytics; IFC-AS = International Finance Corporation advisory services; RAS= reimbursable advisory services.

DB most often informs projects as a project rationale (48 percent of projects) but also serves as a project indicator (29 percent) or project objective (15 percent; appendix A). Given that some projects use DB in more than one way, overall 42 percent (287 of 676) of projects use it as either an indicator or objective or both. The use of DB as a project indicator declined somewhat between FY00–05 and FY06–10, whereas the use of DB as a project objective slightly increased over the same period. A few projects seek to generate or inform DB indicators (13 percent).

Research

Academics and other researchers have found great utility in having time series of DB indicator data updated annually, covering most countries in the world in the areas of regulatory policy covered by the indicators, and it is fertile subject matter for research. The 2018 external audit concludes that the ease of doing business indicators “are one of the World Bank’s most important contributions to research and public policy” (Morck and Shou 2018, 3). DB reports that think tanks and research organizations use the indicators “both for the development of new indexes and to produce research papers” regarding the relationship of business regulation to economic outcomes (World Bank 2016c, 21). Business indicators inform or are used in a large amount of research. In several areas, there are no comparable annually updated data available for so many countries.

The evaluation team found an extensive body of research literature that uses or focuses on DB indicators and the business areas they track. The DB team shared a database of more than 400 articles of relevance to DB from 100 leading journals. IEG’s SLR found close to 1,900 articles of potential relevance based on search terms and a review of abstracts in 10 DB indicator areas. DB2019 reported “more than 3,400 research articles discussing how regulation in the areas measured by Doing Business influence[s] economic outcomes” published in peer-reviewed academic journals, 1,360 of those published in the top 100 journals, and another 9,450 “published as working papers, books, reports, dissertations or research notes” (World Bank 2018b, 32). Doshi, Kelley, and Simmons (2019, 30) point to a significant literature in “critical legal research as well as statistical studies” critiquing the validity of DB indicators, identifying “methodological, substantive and conceptual problems with relying on the EoDB indicators for assessing the business environment.”

A review of DB’s own database from 100 top academic journals indicates that research has concentrated in a few areas, with disproportionate attention to starting a business, trading across borders, and protecting minority investors. IEG’s SLR shows a concentration of rigorous articles about starting a business and trading across borders, with resolving insolvency and getting credit also proving popular. Conversely, getting electricity and registering property have not been widely treated in rigorous studies of outcomes (appendix F).

Doing Business Indicators over Time

The DB indicators have evolved, including the introduction of new indicators and revisions to the methodology of existing ones. Indicator changes are necessary to reflect learning and evidence about their relevance and effectiveness. Given the many limitations noted above, many experts would like to see further changes. A series of changes from DB2015 through DB2017 updated all of the indicators, and many of the updates won praise from subject experts. For example, tax experts appreciated the addition of postfiling requirements. Experts on construction regulation appreciated the addition of a building quality index. IEG acknowledged the validity of eliminating the documents subindicators from trading across borders (World Bank 2019b). In addition, IEG recommended the expansion of indicators to include unrepresented elements of the regulatory environment, such as environmental and competition regulation (World Bank 2015b).

Evidence from this evaluation suggests that additional modifications should be incorporated into future revisions of the indicators to enhance their relevance to country reforms. These modifications can refine the indicators to (i) better capture legal and regulatory attributes with developmental consequence, (ii) better attune to conditions experienced by local businesses, and (iii) adapt to procedural or technological innovations or evolution that alter the nature of what is being measured. The complementary work of DEC’s expert panel can help inform this process.

Each DB indicator change is not without cost, so it matters how such changes are introduced. Academic users can be among the most affected when valued time series are disrupted by changes in methodology. DB can limit (and sometimes has limited) this effect by making available indicators using the old methodology for a period after transitions. Client countries are affected when progress toward targets rooted in one methodology are not rewarded under a new one. Any disruption in the continuity of time series data can affect both client and project targets based on former indicator construction. Evidence suggests that distress increases if client counterparts do not feel consulted or forewarned. If such changes are infrequent and well communicated, they can serve to enhance the value of the DB indicator set. Not all observers agree, and the 2018 external audit recommended that the World Bank “minimize methodology changes except to fix confirmed problems with existing methodology” (Morck and Shue 2018, 2).

- The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development DAC Network on Development Evaluation defines the evaluation criterion relevance as the answer to the question, “Is the intervention [or program or policy] doing the right thing?” To assess it, evaluators explore “how clearly an intervention’s goals and implementation are aligned with beneficiary and stakeholder needs, and the priorities underpinning the intervention. It investigates if target stakeholders view the intervention as useful and valuable” (OECD 2021).

- As noted in the “influence model” theory of change, a low country ranking may come to the attention of leadership through multiple channels, including donors, foreign or domestic investors, the press, or civil society.

- The Omnibus Law, discussed in appendix C, had some limitations, including the weakening of environmental screening.

- An additional difference with enterprise surveys is geographic coverage—typical enterprise surveys cover more cities or regions than does DB.

- Chapter 3 addresses the extent of evidence on individual indicators’ links to outcomes.

- This evaluation does not attempt to generate advice on the design and methodology of individual indicators. That is being explored in greater detail in parallel work commissioned by the World Bank’s Development Economics Vice Presidency.