Creating an Enabling Environment for Private Sector Climate Action

Chapter 2 | Relevance of World Bank Group Lending and Advisory Portfolio

Highlights

The World Bank Group has supported a substantial portfolio of activities that seek to improve enabling environment for private sector climate action, but this portfolio has not increased in recent years.

The Bank Group’s enabling environment support has focused on climate change mitigation more than adaptation; however, the share of World Bank support for adaptation has increased since 2016.

The Bank Group has engaged on the most significant constraints on private sector climate action, such as price and nonprice regulations, which help internalize climate-related externalities and provision of information to the market to improve knowledge and raise awareness, but it has provided insufficient support for risk mitigation and transfer and related institutional development.

The Bank Group has covered sectors with the greatest emissions, but support has focused heavily on the electricity sector, whereas the transport sector has had relatively little support, and there has been little upstream policy reform for agriculture.

The Bank Group’s enabling environment for private sector climate action activities are broadly aligned to the countries and country income groups with the highest emissions.

Countries with greater need for adaptation have received only slightly more adaptation support than other countries.

This chapter assesses the relevance of the Bank Group’s efforts to improve the EEPSCA, provides an overview of the Bank Group portfolio, assesses the degree to which Bank Group support is addressing the most important enabling environment constraints, and assesses whether the Bank Group is concentrating support on the sectors and countries that generate the most GHG emissions or the countries with the greatest need for adaptation.

Portfolio Overview

The Bank Group has approved a substantial portfolio of activities supporting EEPSCA, although this represents only a small portion of its climate change engagement. Between FY13 and FY22, the World Bank approved 268 lending operations containing 375 EEPSCA activities. These operations used both investment project financing (154 projects) and development policy financing (DPF; 102 operations) with less use of other instruments (nine program-for-results operations and three technical assistance loans). World Bank nonlending operations, including EEPSCA analysis, could not be systematically identified. Over the same period, IFC approved 116 AS projects containing 146 EEPSCA activities. These enabling environment–related AS projects targeted governments or broad industry groups rather than individual firms. The EEPSCA portfolio represents only a small portion of the Bank Group’s climate change engagement—projects with EEPSCA activities constitute 11 percent of World Bank lending projects with any climate change co-benefits and 28 percent of IFC AS with any climate change co-benefits. This evaluation defined an EEPSCA activity as the components, subcomponents, or policy actions of an operation that address a distinct enabling environment constraint to private sector climate action. Appendix A provides more details on how activities were defined and identified. In most cases, a project with EEPSCA also includes other activities that are not related to enabling environment, not related to the private sector, or not related to climate change; such other activities are not part of this evaluation.

The Bank Group serves most clients on the EEPSCA. The Bank Group has provided at least some EEPSCA support to 96 countries (out of 134 countries that borrowed from the World Bank during the evaluation period). Most countries with no support are those with relatively small portfolios of lending projects, especially small states.

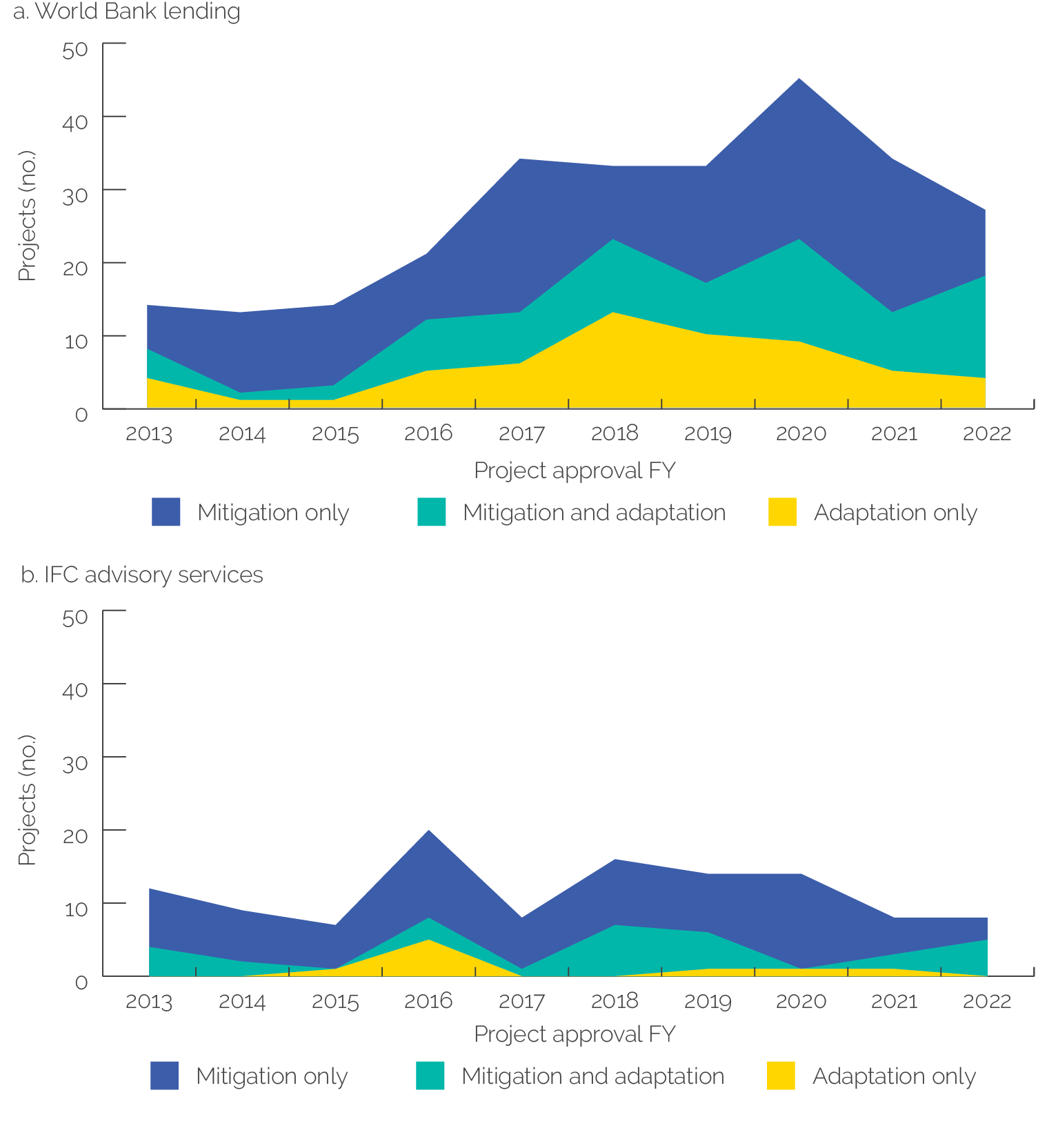

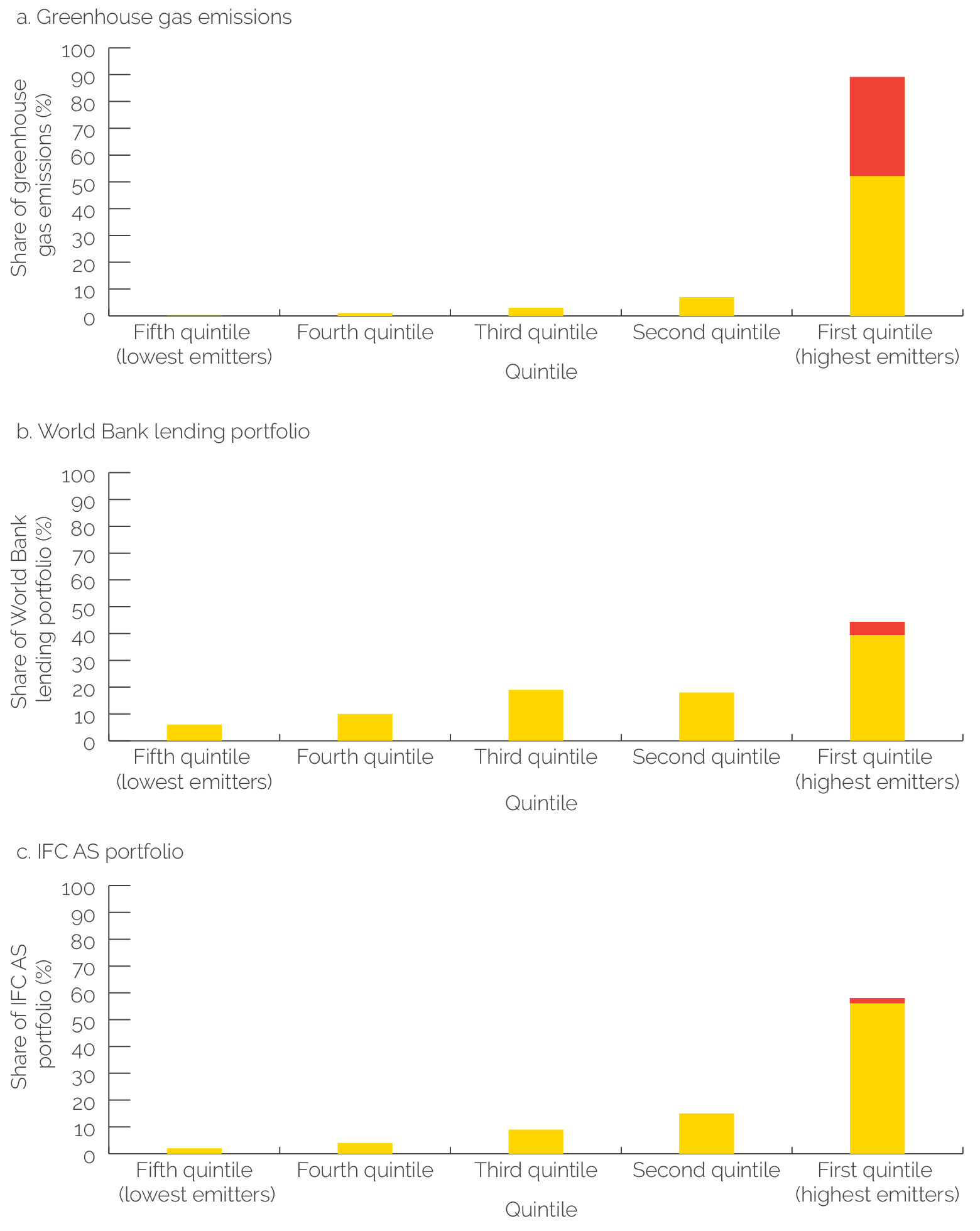

World Bank lending support for EEPSCA increased around the time of the first Bank Group Climate Change Action Plan and has remained steady since then. The Bank Group Climate Change Action Plan 2016–20 confirmed prioritization of the climate change agenda and highlighted the need for climate-related economic transformation to be enabled by a supportive policy and investment environment. Figure 2.1 shows that the number of World Bank lending projects supporting EEPSCA approximately doubled from 2015 to 2017. There was an uptick in EEPSCA support in 2020 with a significant number of COVID-19 response DPF operations that included EEPSCA policy reforms, but this was not sustained. The increasing World Bank support for EEPSCA operations is also partly due to a broader increase in climate change–related operations by the World Bank, which have had a consistent upward trend. For most of the evaluation period, 10–12 percent of all World Bank lending projects with climate change co-benefits included EEPSCA activities; however, this has declined since 2020.

The World Bank’s EEPSCA lending activities have supported climate change mitigation more than climate change adaptation, although the share of support for adaptation has increased since 2016. Across the evaluation period, 50 percent of World Bank EEPSCA lending operations supported mitigation, 22 percent supported adaptation, and 28 percent supported both. Even in low-income countries, EEPSCA support for climate change mitigation has been more common than for adaptation—in these countries, there were 27 EEPSCA projects supporting mitigation, 7 projects supporting adaptation, and 9 projects supporting both. However, projects supporting climate change mitigation could also be seen as promoting green growth or low-carbon development.

The World Bank’s climate change mitigation support has focused on provision of financial and nonfinancial incentives. The incentives were mostly directed to renewable energy generation (such as feed-in tariffs and credit lines), cost-reflective electricity pricing, removal of subsidies to state-owned electricity companies, and mitigation of financial and technical risks associated with investment in renewable energy. Others include support to legal and institutional reforms required to stimulate a pipeline of viable renewable energy projects and to enhance competitive procurement of electricity from independent renewable energy producers. Non-energy-related mitigation activities include supporting governments to develop incentive mechanisms for reduced GHG emissions mostly from afforestation, for example, through payment for ecosystem services, emission reduction payments, and carbon credit schemes.

Figure 2.1. World Bank Group Lending and International Finance Corporation Advisory Portfolio for EEPSCA, Fiscal Years 2013–22

Source: Independent Evaluation Group portfolio analysis.

Note: EEPSCA = enabling environment for private sector climate action; FY = fiscal year; IFC = International Finance Corporation.

The World Bank’s climate change adaptation support has provided information and financial and nonfinancial incentives and has focused mostly on the public sector. The World Bank’s climate change adaptation support has included the provision of climate and hydrological data (as well as mapping of climate hazards) to the private sector, the introduction of resilient building codes, and financial incentives to support investment in climate change adaptation technologies. Many of the World Bank’s climate change adaptation activities have been focused on the public sector, rather than on private sector enabling environment, because many forms of climate change adaptation are public goods.

The main World Bank activity that supported both climate change mitigation and adaptation is the facilitation of climate-related research and development that benefits the private sector. This included, in particular, strengthening industry-academia linkages to accelerate the transfer of relevant climate mitigation and adaptation techniques from academia to the private sector. Other activities in support of both mitigation and adaptation include financial incentives to promote adoption of climate-smart agriculture (CSA) practices, sustainable forestry regulations and incentives, resilient building standards that incorporate energy efficiency, and green taxonomies.

The World Bank has also supported EEPSCA through nonlending work. The World Bank has approved many nonlending activities that support EEPSCA, including diagnostics, knowledge work, AS, and capacity building. However, the evaluation could not identify them systematically because these activities are not tagged as to whether they are likely to deliver climate change benefits. Evaluation case studies show that nonlending work has played a critical role in diagnosing constraints, identifying priority actions and serving as the basis for lending operations, supporting policy dialogue and raising awareness, and building client capacity.

IFC support for EEPSCA has remained flat through the period. As shown in figure 2.1, despite the increasing Bank Group corporate prioritization of climate change, EEPSCA IFC AS support has not increased through the evaluation period. Enabling environment support has also remained a relatively steady share of all climate change–related IFC AS; however, this share has been lower in 2021 and 2022 in part because of an increase in the number of climate change–related IFC AS that were not related to enabling environment.1 This evaluation is not able to draw definitive conclusions on the reasons behind the lack of increasing support. One reason may be the difficulty of developing private sector business models in adaptation (discussed further in this chapter). Over time, there has also been inconsistent IFC management prioritization of AS, especially government or industry facing AS that were not specifically linked to IFC investments. IFC internal restructurings, including the creation of upstream advisory resources and subsequent decentralization to the Regional departments, may have affected the teams’ ability to work in a coordinated fashion on identifying and standardizing new business lines. In 2018, IFC introduced its concept of “upstream” work, which seeks to remove barriers to investment, enhance the operating environment for private business, and identify and create new investment projects. The upstream approach has the potential to unlock enabling environment opportunities if resources are managed in a way that creates new business models. However, although the EEPSCA IFC AS portfolio includes 28 upstream advisory projects, these have not been enough to increase the overall trend. Thus far, IFC EEPSCA engagements have focused on a few critical activities (public-private partnership [PPP] advisory especially for solar power, sustainable banking, and green buildings) where IFC built internal capacity. Broadening in other areas could require further capacity development.

IFC has provided EEPSCA support for climate change mitigation, but relatively little EEPSCA support for climate change adaptation. Across the evaluation period, 67 percent of EEPSCA IFC AS supported climate change mitigation, 8 percent supported climate change adaptation, and 25 percent supported both. Many activities that supported both have been for sustainable banking, which has largely prioritized climate change mitigation. IFC was a pioneer in supporting a voluntary community of financial sector regulatory agencies and banking associations from countries committed to advancing sustainable finance (Sustainable Banking and Finance Network). This association, which includes 43 countries, is aimed at improving environmental and social risk management (including disclosure of climate risks) and increased capital flows to activities with positive climate, environmental, and social impact.

IFC AS has supported climate action in three main areas:

- Climate change mitigation, including business lines related to PPP transaction AS for renewable energy projects (such as through the scaling solar program), voluntary green building standards through the Excellence in Design for Greater Efficiencies program,2 provision of financial incentives to promote climate mitigation activities, and other support to enable regulators and industry groups to build a pipeline of bankable projects in the finance and green building sectors.

- Climate change adaptation, including climate risk insurance products for farmers, regulations for banks and other financial sector intermediaries to assess their exposure to climate risk, and economic incentives for efficient water use by private firms.

- Climate change mitigation and adaptation, including improvements to climate-related environmental, social, and governance frameworks in the financial sector and design of green taxonomies that help identify sectors and activities that contribute to climate action.

One reason the Bank Group’s EEPSCA adaptation support is lower than for mitigation is the limited global progress in the development of business models for investments in climate adaptation. Lower Bank Group support for adaptation reflects the external private sector environment. Climate change adaptation activities often have public good characteristics that lack revenue streams and thus are difficult to derive bankable business models for the private sector. In addition, adaptation needs are often dependent on specific local context and likely climate change impacts; therefore, an activity that is adaptive in one context may not be in another. Globally, the private sector has less experience with adaptation investments, whereas many forms of mitigation have become standardized business lines. For some forms of adaptation, it may be difficult for the Bank Group to develop private sector business models in these areas without demonstrated models in high-income countries. However, there may also be opportunities to innovate and extend business models to client countries by addressing the specific constraints that hinder replication. The difficulty of increasing private sector participation in adaptation is a particular challenge for low-income countries, which have the greatest need for adaptation. In addition, low-income countries face a higher cost of funding, which compounds the challenge.

Relevance of World Bank Group EEPSCA Lending and Advisory Activities to Key Constraints to Private Sector Climate Action

This section assesses the degree to which Bank Group support is addressing the most important enabling environment constraints for private sector climate action. It does so by developing a typology of the most important constraints using a structured literature review of policy papers on climate change enabling environment and then assessing the alignment of the Bank Group portfolio to those constraints. The methodology for the literature review and development of the typology is described in appendix A.

A Typology of Enabling Environment Constraints

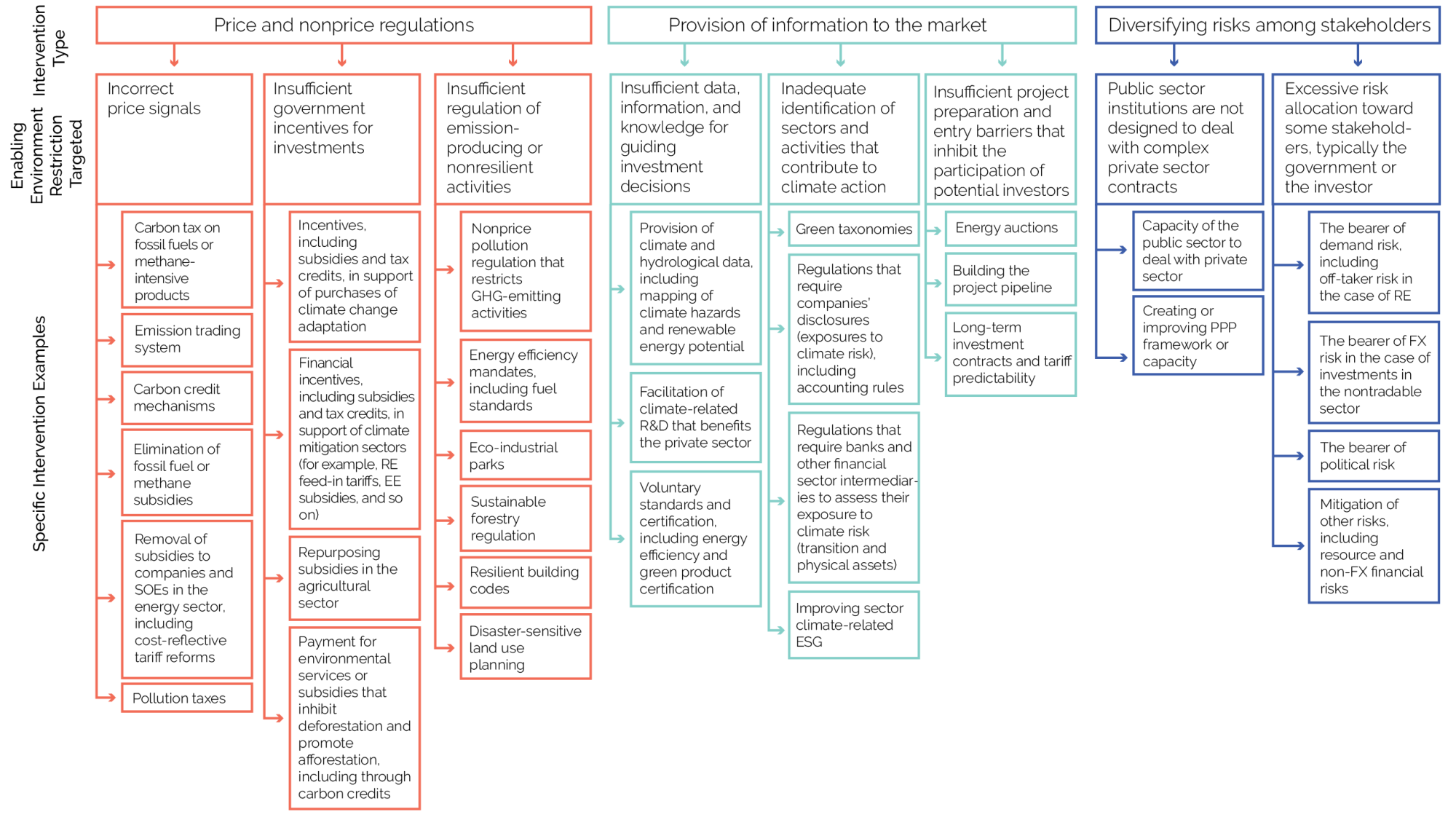

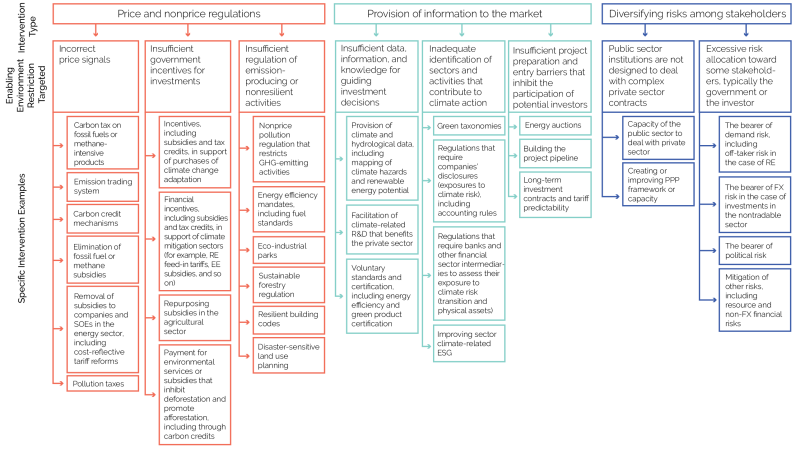

The evaluation groups enabling environment constraints on private sector climate action under three broad categories. As described in the evaluation framework (figure 1.1), three key factors are needed for markets to operate efficiently in the climate space: (i) price and nonprice regulations, (ii) market information, and (iii) risk management and related institutional development. Figure 2.2 provides a detailed typology of these three factors.

- Price and nonprice regulation. Climate change mitigation (and to a lesser extent adaptation) involves negative or positive externalities associated with GHG emissions or climate resilience. Prices that force users to internalize these distortions, including carbon taxes and reduction of subsidies to fossil fuels, are at the core of setting appropriate market incentives. The private sector is also sensitive to government incentives that can help direct investment into sectors that support climate mitigation. Instruments such as tax incentives and other subsidies for renewable energy and green buildings and payments for ecosystem services for agroforestry operations create incentives for investments in these sectors. In addition, through the enactment of regulations, governments can discourage emission-producing or nonresilient activities, including pollution regulation that restricts GHG-emitting activities, energy efficiency mandates and fuel standards, or resilient building codes.

- Market information. The private sector requires adequate information to make investment decisions, especially for climate change–related sectors and actions that may be new or unfamiliar. In this context, actions and interventions that increase awareness by providing data, information, and knowledge for guiding investment decisions—including mapping of climate hazards, voluntary standards and certification of green products, and facilitation of climate-related research and development—improve conditions for private investment. Considering the increasing investor appetite for green investments, actions that promote identification of sectors and activities that contribute to climate action are useful to guide investment decisions. Finally, interventions that help countries develop pipelines of investible projects are important in bringing opportunities to investors.

- Risk management and institutions. Considering that large climate-related investments, including in infrastructure, involve significant capital and long payback periods, private sector participants are sensitive to risk. Excessive risks need to be mitigated or transferred, and risks need to be allocated to the parties best able to bear them. Institutional capacity of the public sector is essential for building credibility with private sector counterparts. Because most government institutions related to building public infrastructure were designed with the purpose of executing their budgets—as opposed to designing and managing contracts with private sector counterparts—interventions and actions that support increases in the institutional capacity of the public sector are important in building trust and enabling the development of risk-sharing agreements between private and public counterparts. In large climate-related infrastructure projects, risks typically include counterparty, credit, demand, foreign exchange, financing, operational, and force majeure, among others. Stakeholders typically include public institutions, such as a line ministry or a state-owned enterprise; private sector investors; financiers, including banks and bondholders; insurance companies and other financial intermediaries; and final users. Although initial risk management schemes typically rely on government guarantees, interventions that facilitate risk allocation to the party best able to bear them are effective in channeling more private sector solutions. Risk management arrangements are bounded by contracts that establish the rights and obligations of each of the parties, including compensation when some of the parties do not fulfill their obligations. Private investors are keen on ensuring the presence of an impartial dispute settlement system before engaging in any contract.

Figure 2.2. Enabling Environment Constraints to Private Sector Climate Action

Source: Evaluation team’s conception based on structured literature review.

Note: EE = energy efficiency; ESG = environmental, social, and governance; FX = foreign exchange; GHG = greenhouse gas; PPP = public-private partnership; RE = renewable energy; R&D = research and development; SOE = state-owned enterprise.

Alignment of World Bank Group Portfolio to Enabling Environment Constraints

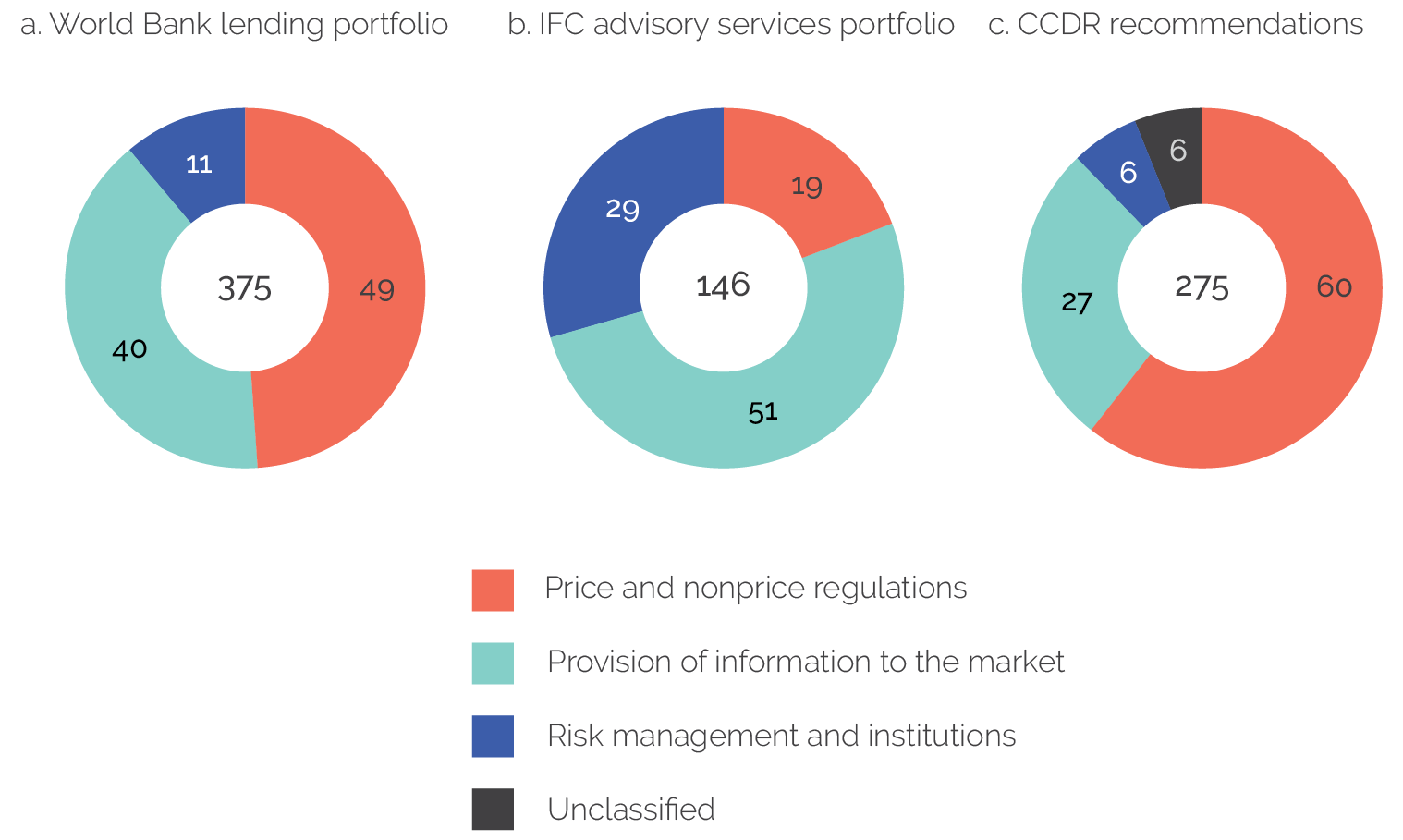

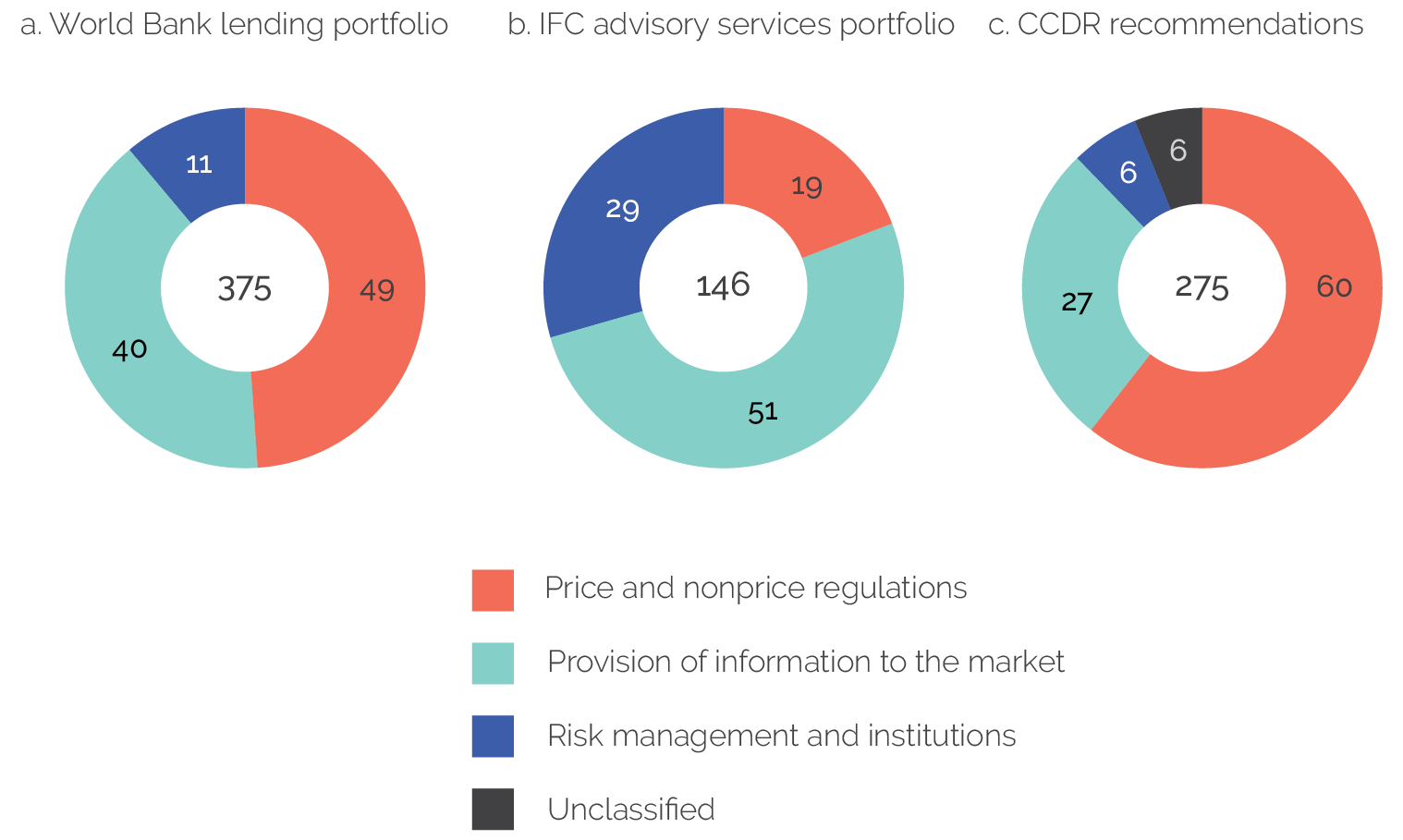

This section analyzes the Bank Group’s EEPSCA activities and its forward-looking policy recommendations against the typology described in chapter 2. It finds that the Bank Group has focused on price and nonprice regulations and provision of information to the market but has provided limited support for risk management and institutions. The findings are summarized in figure 2.3, and more detail is provided in appendix B. The evaluation identified which type of constraint was being addressed by each of the 375 EEPSCA activities in World Bank lending operations and 146 EEPSCA activities in IFC AS projects between FY13 and FY22. In addition, this evaluation analyzed policy recommendations included in the first 23 CCDRs produced by November 2022 against the same typology. These policy actions provide a signal of the intended future directions of Bank Group support. Of the 937 policy recommendations in CCDRs, 275 were related to the enabling environment for the private sector. Although the evaluation could not determine what the optimal share of Bank Group support should be for each type of constraint, it identified areas of strong support and potential gaps. The Bank Group’s EEPSCA work has focused on price and nonprice regulations and provision of information to the market. The World Bank has provided little support for risk management and institutions, and these are a small share of CCDR policy recommendations. Almost 30 percent of the IFC AS activities are related to risk-sharing between the private and public sectors, but they are narrowly focused.

Figure 2.3. Breakdown of EEPSCA Activities and Recommendations, by Constraint Typology

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: The World Bank lending and IFC advisory services portfolios, respectively, include 375 and 146 EEPSCA activities approved in fiscal years 2013–22. For CCDRs, the figure includes 275 EEPSCA recommendations from the first 23 CCDRs. CCDR = Country Climate and Development Report; EEPSCA = enabling environment for private sector climate action; IFC = International Finance Corporation.

Price and Nonprice Regulation

The World Bank has provided significant support in lending operations for activities that help include externalities in price signals, provide incentives to climate-related sectors, or regulate high-emitting or nonresilient activities. The World Bank has frequently supported cost-effective tariffs for utilities; carbon crediting mechanisms; payment for environmental service mechanisms addressing deforestation; other financial incentives, such as subsidies for renewable energy; and climate-related standards and regulations, such as resilient building codes, sustainable forestry regulations, and energy efficiency mandates.

Nevertheless, the World Bank has infrequently supported key activities that provide broad incentives for climate action, such as carbon pricing. Although interventions that affect the relative prices of clean compared with dirty technologies across multiple sectors are powerful ways of incentivizing action, their high visibility makes them contentious and creates political economy barriers. Only 12 activities in lending projects supported implementing or increasing carbon taxes or reducing fossil fuel subsidies. In addition, the World Bank has only six lending operations related to repurposing subsidies in the agricultural sector, where the Bank Group is only beginning to engage. There were few examples of support for air pollution regulations, which could disincentivize high-emitting technologies. Carbon pricing is often proposed as the optimal solution, but the World Bank supported carbon pricing programs through lending activities in only three countries (Colombia, North Macedonia, and South Africa). This is consistent with the slow global pace on carbon pricing around the world, as documented in the State and Trends of Carbon Pricing 2023 report (World Bank 2023b). Chapter 3 describes political economy barriers and how the Bank Group has engaged on them.

IFC seldom supported activities that addressed price and nonprice regulations, consistent with this not being its institutional comparative advantage. IFC worked with governments to develop financial and nonfinancial incentives for private investment in solar power and green buildings, which were sectors where IFC established strong internal capacity. Outside of such areas, the World Bank is often better placed to provide upstream policy support on price and nonprice regulations because high-level policy support is not part of IFC core mandates.

CCDRs have heavily emphasized price and nonprice regulations (60 percent of EEPSCA recommendations) and have ambitious proposals for carbon taxes. Approximately one-third of CCDRs’ recommendations are related to the use of prices as an incentive for attracting private sector investments, including implementing or increasing carbon taxes, reducing fossil fuel or methane subsidies, and removing subsidies to companies and state-owned enterprises in the energy sector. Across the 23 CCDRs covered, 14 have recommendations for carbon taxes and 11 for reducing fuel or methane subsidies. There is some disconnect between these ambitious forward-looking proposals and the relative lack of global progress or World Bank support for carbon taxes or fossil fuel subsidies during the evaluation period.3 The remaining policy recommendations included in the CCDRs relate to regulation of emission-producing or nonresilient activities (primarily through mandatory standards for energy efficiency and resilient building codes) and to provision of sectoral incentives.

Market Information

The World Bank frequently supported lending operations that addressed insufficient information. The World Bank frequently helped clients build project pipelines, such as through power sector plans that signal to the market that there will be investible projects. Approximately one-third of the activities related to market information provide support to project preparation. The World Bank also helped improve the predictability of tariffs in public-private contracts and built client capacity to conduct energy auctions. In addition, the World Bank frequently facilitated climate-related research and development that benefit the private sector and provided climatological data, including mapping of climate hazards and renewable energy potential. Few interventions addressed voluntary standards and certification for energy efficiency and green products because these were addressed more by IFC.

There are only a few World Bank lending operations for development of regulations to identify climate-related sectors to investors, such as through green taxonomies. Although these are promising activities for bringing private sector investments, they are relatively new even in high-income countries. For example, it was only in 2020 that the European Union adopted its green taxonomy and that the guidelines for greening the financial sector became available. However, the evaluation could not identify the extent to which these goals are supported through nonlending work.

IFC provided substantial support to improve information to markets, especially through support to develop project pipelines. This support was largely for (i) the adoption of voluntary standards (predominantly resource efficient and zero carbon building standards; Excellence in Design for Greater Efficiencies), mostly by raising awareness among regulators and industry groups of the business case for green buildings; (ii) the creation of project pipelines; and (iii) building capacity of financial institutions for sustainable finance. Support for the creation of project pipelines accounts for about one-third of the IFC AS activities related to the provision of market information.

CCDRs recommended many policy actions related to information but rarely encouraged activities that would help build pipelines of investible projects. CCDRs frequently included policy recommendations related to green taxonomies and disclosures and data for guiding investment decisions, such as climatological and hydrological data or voluntary standards and certification. However, they rarely included midstream activities to build project pipelines, in contrast to the substantial World Bank and IFC activities on this topic.

Risk Management and Institutions

The World Bank rarely supported lending operations that improve risk management or related capacity of the public sector, including risk-sharing arrangements between public institutions and private investors. Only 11 percent of World Bank EEPSCA lending activities addressed these types of constraints. The World Bank provided some advisory support for improving institutional, legal, and operational frameworks for PPPs, helped establish partial credit guarantee schemes for financial institutions and investors financing green projects, and supported the design and implementation of private insurance products for disasters caused by natural hazard. To check if this gap in risk management lending activities was addressed by nonlending work, the evaluation conducted a systematic identification of climate-related nonlending activities on PPP. This review identified 59 enabling environment activities related to PPP across 20 countries, largely in the water, transport, and energy sectors.

IFC addressed risk allocation issues in solar power but seldom engaged in other risk management activities. IFC provided PPP transaction AS for solar power through its scaling solar program across multiple regions. There are also transaction AS for streetlight tendering activities for several cities in Brazil. Among other sectors, engagements include a waste to energy activity in Bangladesh and structuring of the private sector component of a bus rapid transit in Senegal. These AS address risk allocation by helping governments establish contract terms that determine which risks are held by different stakeholders.

CCDRs rarely proposed policies related to risk mitigation or related institutional development, which may stem from CCDRs’ prioritization criteria. Only 6 percent of CCDR policy recommendations addressed these issues, primarily on actions to improve PPP frameworks in 4 out of the 23 countries covered (Jordan, Malawi, Indonesia, and the Arab Republic of Egypt). The absence of support for institutional capacity building and reform may be a consequence of the prioritization criteria used in CCDRs, which encourage urgent actions with immediate payoffs rather than those that are less urgent or have trade-offs (World Bank Group 2022b, figure 16).

Insufficient emphasis on risk management and public sector institutional capacity has potential effects on the ability of countries to mobilize private sector climate action at scale. Adequate risk-sharing arrangements are the cornerstone for financing climate-related opportunities at scale. Stronger public sector institutions open opportunities for better risk-sharing, especially in the presence of more advanced financial systems. Although contractual arrangements that allocate counterparty, demand, credit, and foreign exchange risk to government counterparts (including guarantees) may boost the interest of private sector investors, they are not scalable, considering the high levels of government indebtedness and additional government capacity to fund future commitments. These contractual arrangements replace explicit debt with implicit debt, in the form of additional contingent liabilities. External literature (CFLI, EDFI, and GIF 2021; Grimm and Boukerche 2020; OECD 2021, 2022b; World Bank Group, UNDP, and GIF 2020) suggests that allocating risks across stakeholders (government, equity investors, bondholders, banks, insurance companies, multilateral organizations, and other financial intermediaries) based on reliable contracts and institutions allows scalability of private sector investments. The structure of contracts may evolve over time to reflect the strengths and weaknesses of different stakeholders, the depth of the capital market, and the trust of the private sector in public institutions. Although some recent articles (Li, Natalucci, and Ananthakrishnan 2022; Sekyoung Choi, Zhou, and Laxton 2022) put emphasis on the role that multilateral organizations can play in de-risking private sector portfolios, credit risk is not the only variable that inhibits private sector participation, and other risks are expected to be allocated to different stakeholders. In addition, the lack of activities in low-income countries may reflect some additional structural issues that may need to be addressed.

Relevance of World Bank Group EEPSCA Lending and Advisory Activities for Countries and Sectors

The evaluation assessed whether Bank Group EEPSCA activities were targeted toward the sectors and countries with the highest GHG emissions. The evaluation classified all Bank Group EEPSCA activities by the economic sector they addressed and compared these activities to external data on GHG emission sources (World Resources Institute Climate Analysis Indicators Tool).4 The analysis focuses on emissions from Bank Group client countries (countries with at least one lending operation during FY13–22), which collectively generated 66 percent of global emissions during 2013–19. The historical stock of emissions does not come from Bank Group client countries, and Bank Group client countries have much lower emissions per capita than nonclients, but the Bank Group does not engage directly with nonclients. If the Bank Group were strategically targeting emission reductions of its clients, this would imply that it would conduct more activities in sectors and countries with higher GHG emissions.

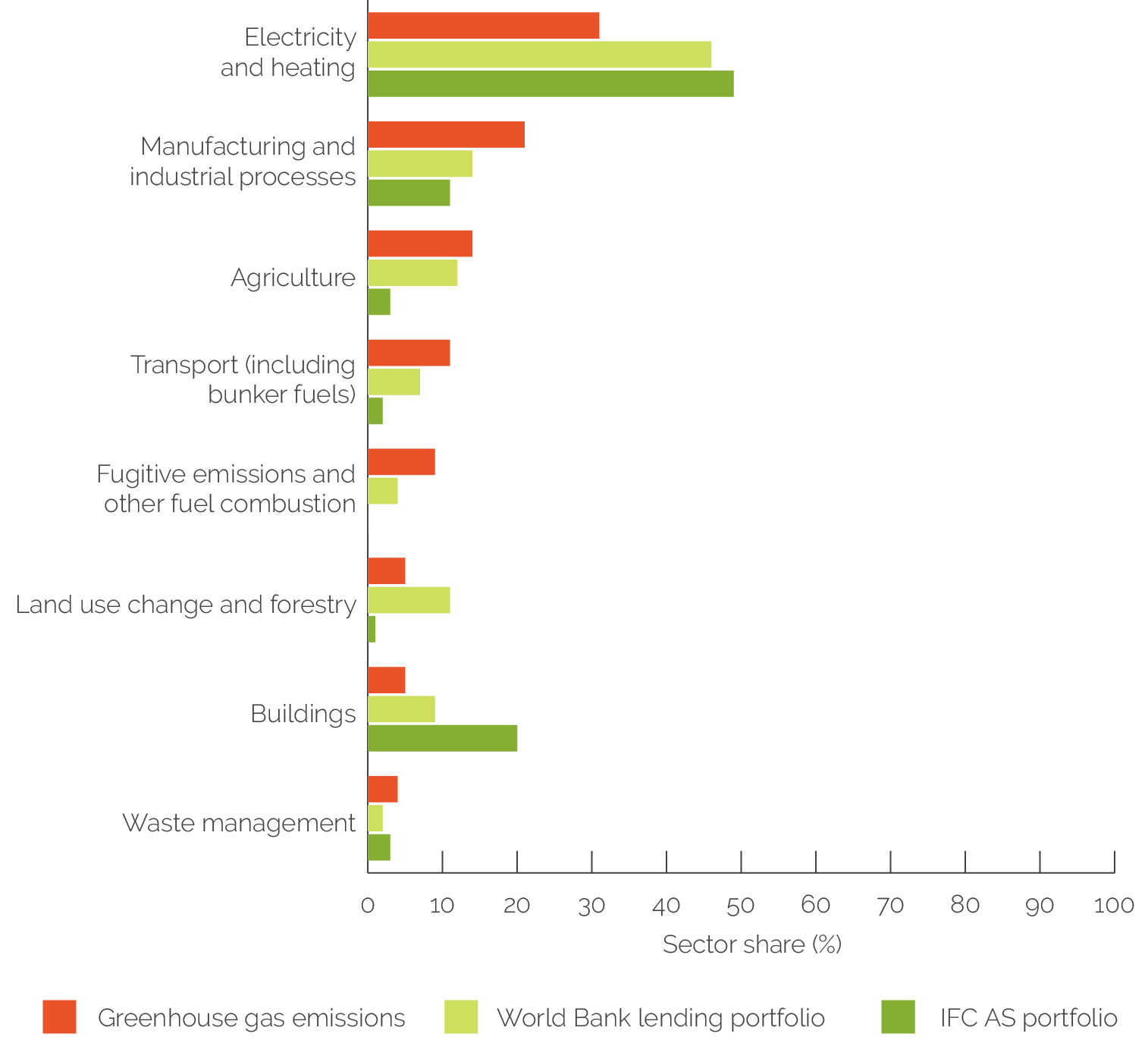

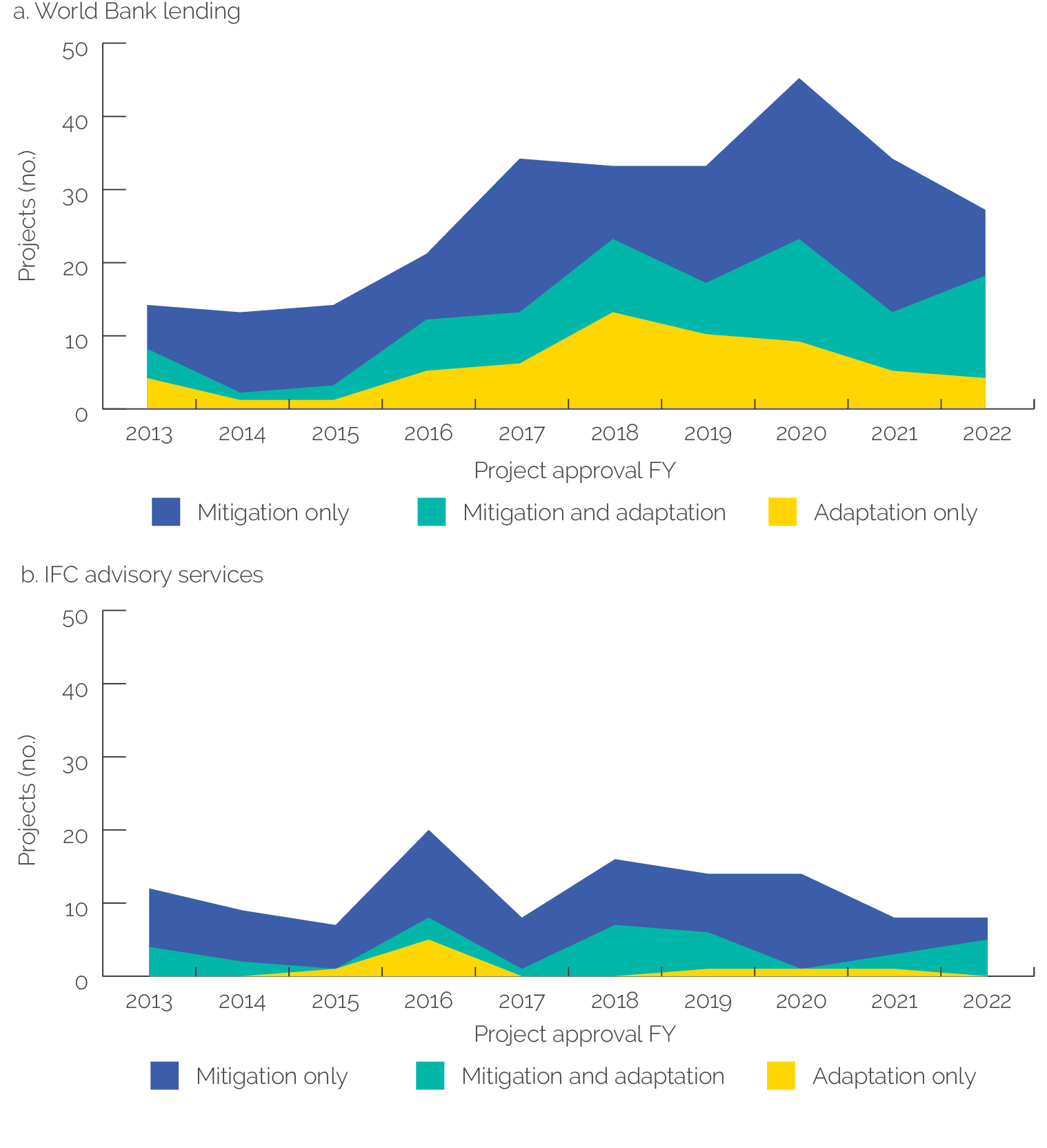

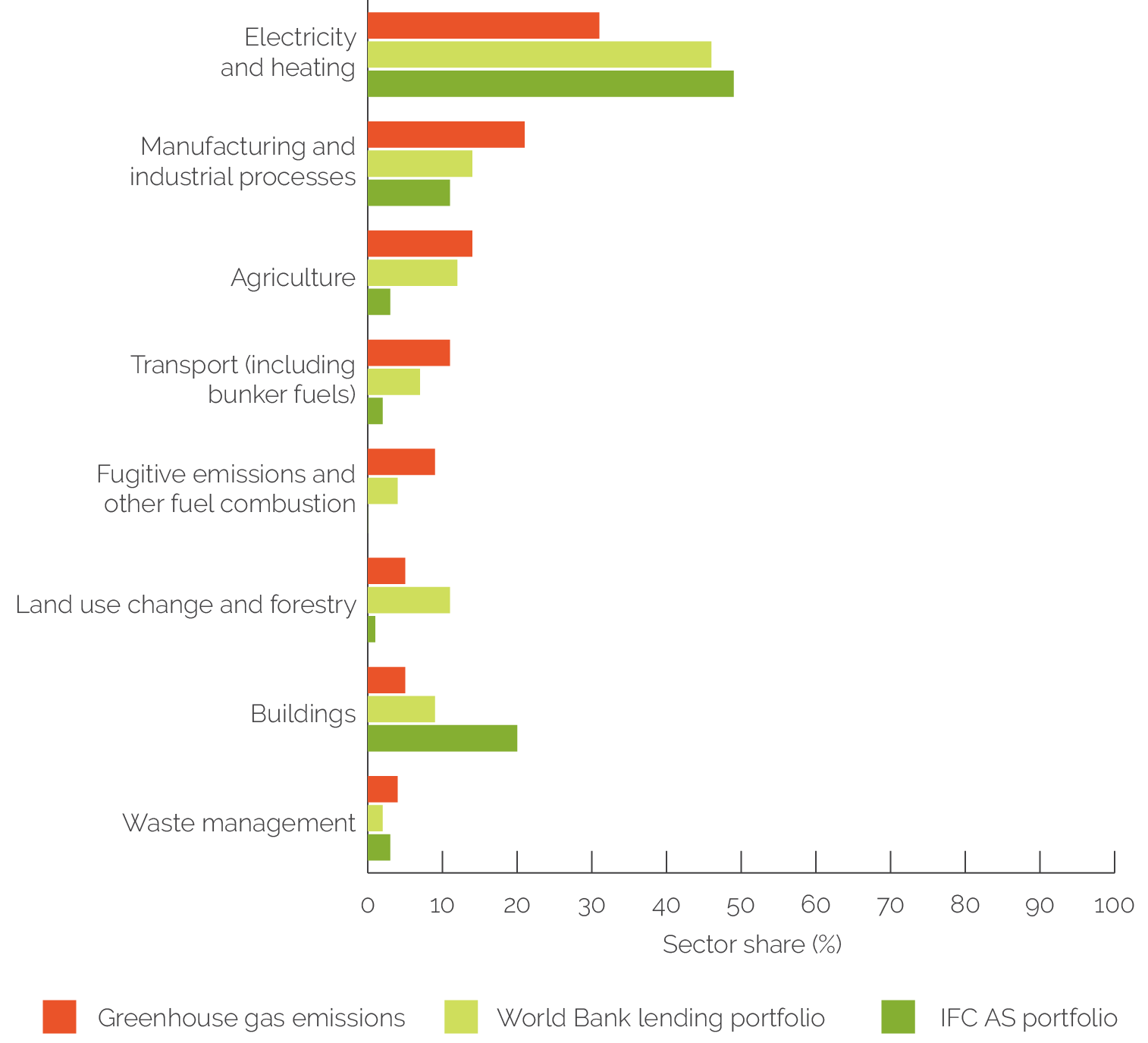

The Bank Group has provided some EEPSCA support across all sectors that are significant sources of GHG emissions in client countries. The Bank Group has provided at least some support for enabling environment for private sector climate change mitigation in all major emission source categories (figure 2.4).

The Bank Group EEPSCA support for climate change mitigation is somewhat aligned with sectors that generate GHG emissions but has had a heavy emphasis on electricity relative to other sources of emissions. Figure 2.4 shows that nearly half of Bank Group EEPSCA support (46 percent for World Bank; 49 percent for IFC) has been for electricity and heating (primarily renewable energy and energy efficiency), which constitutes 31 percent of emissions in client countries. Support for other major sectors (especially transport, agriculture, and manufacturing and industrial processes) is lower than their share of emissions. This may be because it has been easier to mobilize private capital in the electricity sector (particularly renewable energy) than for many other climate change mitigation activities. In turn, this may be due to (i) the electricity sector having standard business models for private sector participation; (ii) the Bank Group having developed specific capacity in the energy sectors, including skills and financial resources; and (iii) the rapid global growth of the renewable energy sector, with high client and investor demand. The share of GHG emissions in client countries from electricity and heating has been rising over time (from 22 percent in 1990 to 31 percent in 2019).

Figure 2.4. Greenhouse Gas Emissions by Sector in World Bank Group Client Countries and World Bank Group EEPSCA Project Support by Sector

Source: Independent Evaluation Group analysis using emissions data from the World Resources Institute Climate Analysis Indicators Tool for 2013–19 and World Bank Group portfolio data.

Note: To align the sectors in the World Bank and IFC portfolio charts with those in the greenhouse gas emissions chart, World Bank Group EEPSCA activities that do not map to specific sectors (for example, on sustainable banking) are not shown in the portfolio charts. Sector shares of the World Bank lending and IFC AS portfolios are not mutually exclusive because a single World Bank or IFC project can contain EEPSCA activities related to multiple sectors. AS = advisory services; EEPSCA = enabling environment for private sector climate action; IFC = International Finance Corporation.

The Bank Group’s support for EEPSCA in the transport sector has been low. Transport-related mitigation activities have included removal of subsidies and the imposition of a carbon tax on liquid fossil fuels and the provision of economic incentives to assist mass transit service operators with switching to electric vehicles. However, the overall level of support for EEPSCA in the transport sector has been relatively low (7 percent of the EEPSCA portfolio), and none of the transport-related lending projects were led by the Transport Global Practice (although transport specialists supported operations led by other Global Practices and led important nonlending work). This is consistent with findings from an Independent Evaluation Group Evaluation Insight Note on decarbonization in the transport sector (World Bank 2022b), which did not have a specific focus on private sector but noted that the World Bank could do more to use DPF to support transport decarbonization policies and reforms. Outside of the evaluation portfolio, the World Bank has supported bus rapid transit systems, including in low-income countries, but this support has been through direct financing rather than enabling environment for the private sector. IFC has only two EEPSCA projects related to transport—one related to bus rapid transit and the other related to municipal infrastructure.

The Bank Group has supported research on CSA practices and financing mechanisms for farmers to invest in these practices but has done relatively little on upstream policy reform. In the agriculture sector, the World Bank has supported research and dissemination of CSA practices coupled with the provision of matching grants and other financial incentives to support farmers’ investment in CSA techniques. However, World Bank support for CSA was largely through downstream activities outside of the evaluations’ scope, particularly the provision of extension services to farmers, rather than through enabling environment activities. There has been very little use of DPF in agriculture (only 2 out of 102 DPF operations in the EEPSCA portfolio related to agriculture), perhaps because of the substantial political economy barriers to reforms that may affect large numbers of poor farmers but also because the World Bank has not prioritized enabling environment or policy issues. The World Bank has published a flagship report on repurposing agricultural subsidies and other policies to support climate action (Gautam et al. 2022), but the agenda is nascent. The first CCDRs place little emphasis on agricultural subsidy reform, which is only beginning to be brought into country policy dialogue. IFC has only three EEPSCA projects related to agriculture; these support financial technology adoption by farmers, reduced deforestation from cattle ranching, and promotion of good agricultural practices.

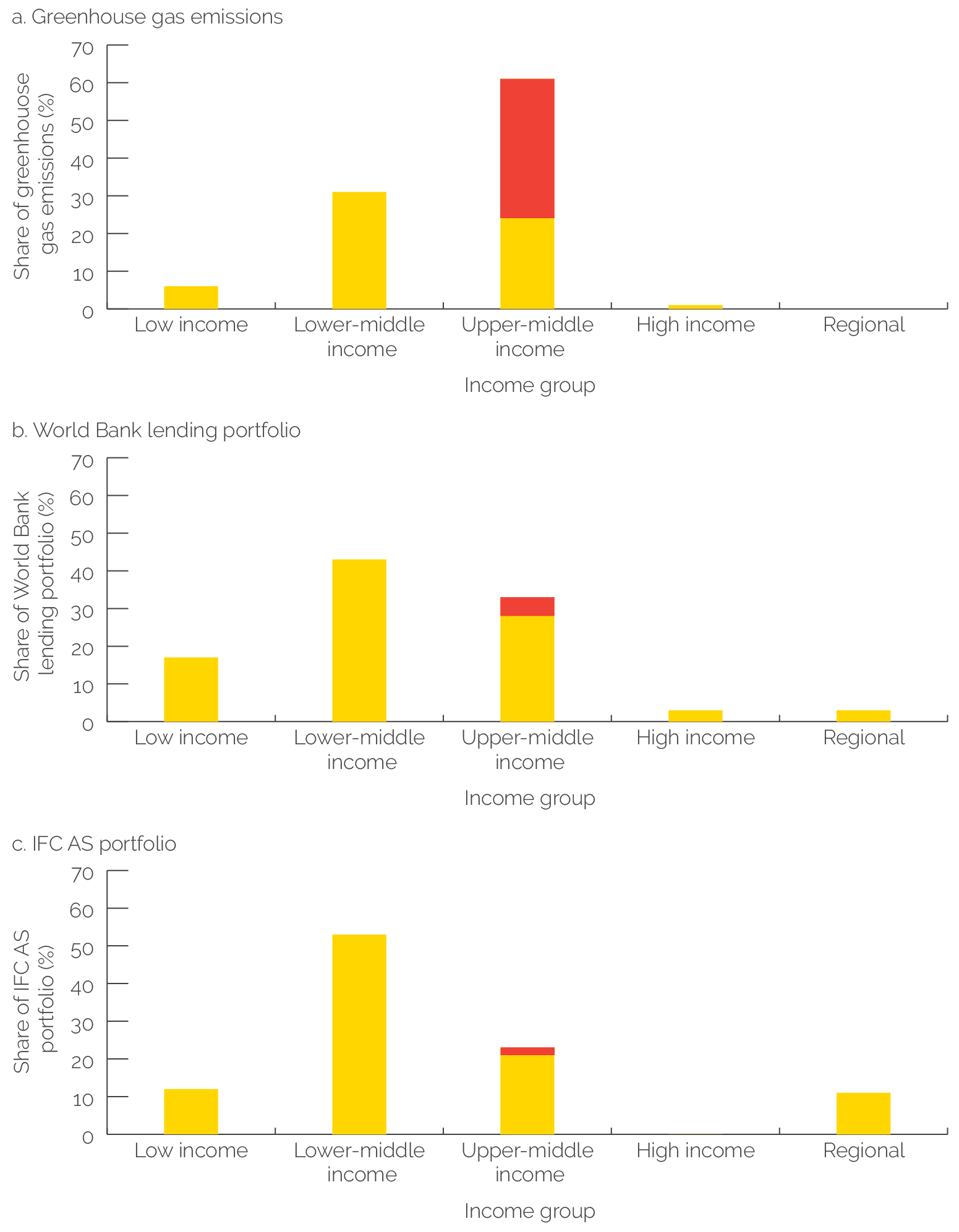

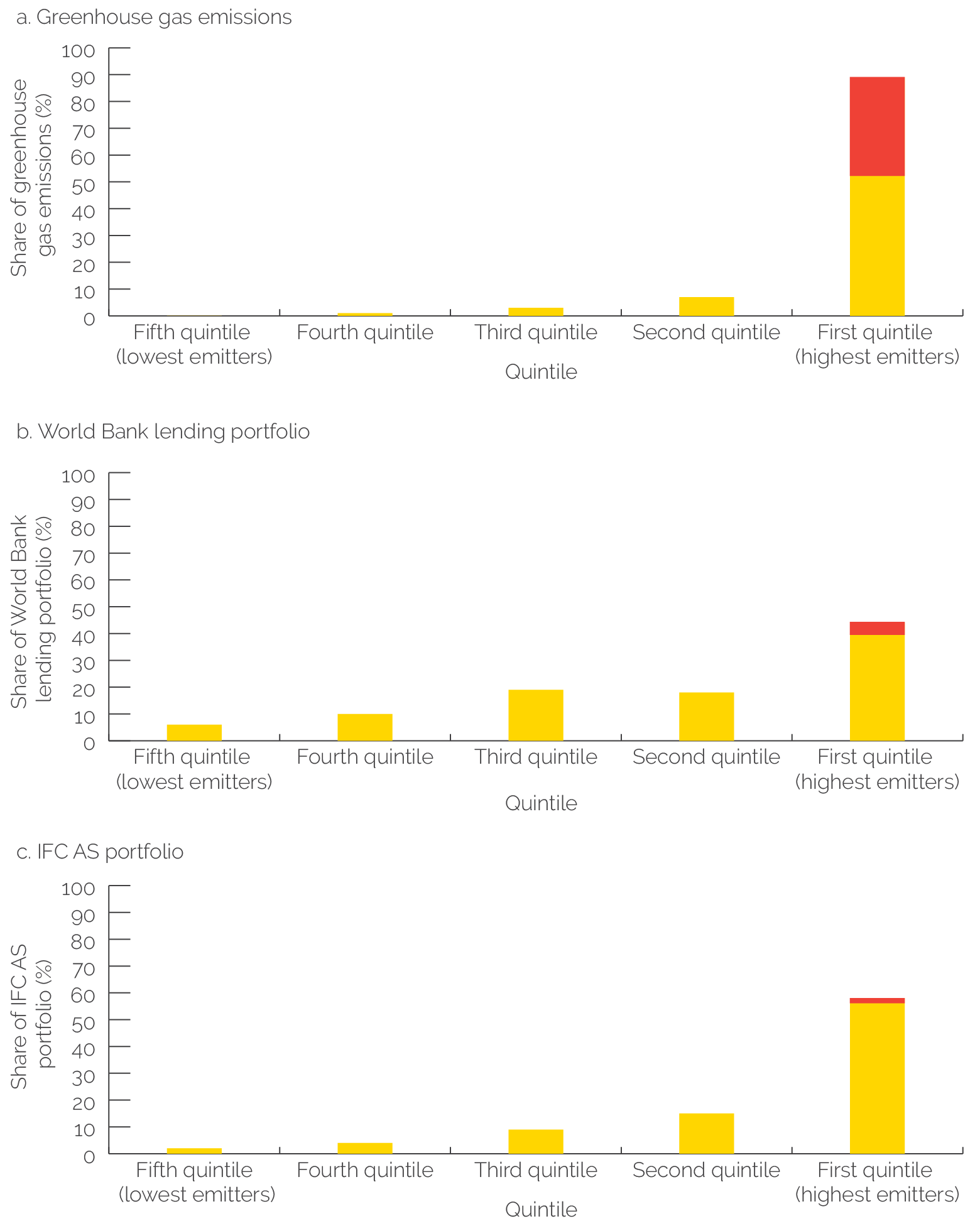

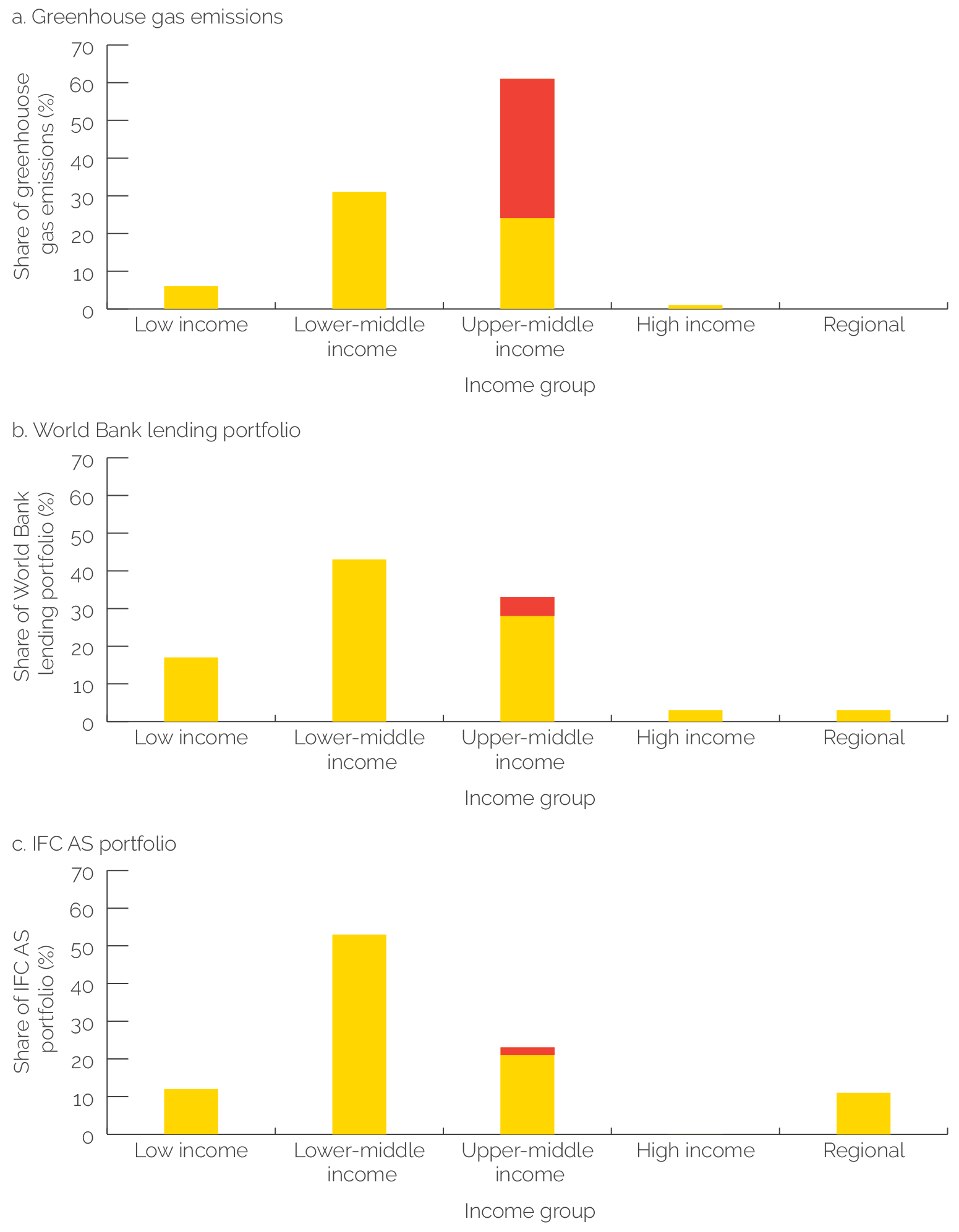

The Bank Group’s EEPSCA activities are broadly aligned to the countries with the highest emissions. Figure 2.5 shows that only 44 percent of World Bank EEPSCA lending operations and 58 percent of IFC EEPSCA AS target the top quintile of emitters among Bank Group client countries, which produce 89 percent of client country emissions. However, this is due mostly to relatively low Bank Group support to China for World Bank lending and IFC AS. Excluding China, 39 percent of World Bank EEPSCA projects and 56 percent of IFC EEPSCA AS are in the other highest-quintile emitting client countries, which generate 52 percent of emissions. The top-quintile countries with the most EEPSCA projects supporting climate change mitigation are Brazil, China, Colombia, India, Indonesia, and Vietnam. There are no significant gaps in World Bank EEPSCA support among high-emitting countries—the only top-quintile emitting countries with very few EEPSCA projects are countries that borrow infrequently from the World Bank, such as the Islamic Republic of Iran, the Russian Federation, and Thailand.

The Bank Group’s EEPSCA activities are broadly aligned to the country income groups with the highest emissions. Figure 2.6 shows that if China is excluded, 25 percent of client country emissions come from upper-middle-income countries, with 29 percent of World Bank EEPSCA projects and 21 percent of IFC EEPSCA AS in other upper-middle-income countries. Although the share of Bank Group EEPSCA mitigation activities in low-income countries is higher than their share of emissions, these activities are generally low-carbon-emitting activities with substantial development benefits, such as expanding energy supply and access in a low-carbon manner.

The evaluation assessed the alignment of Bank Group EEPSCA activities with client country adaptation needs. The evaluation compared the Bank Group EEPSCA portfolio with an external benchmark of country needs for adaptation (the Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative Country Index).5 This index uses 45 indicators to rank countries based on their vulnerability to climate change.

Figure 2.5. Greenhouse Gas Emissions in Client Countries and EEPSCA Project Portfolio, by Emissions Quintile

Sources: Independent Evaluation Group team portfolio; emissions data from the World Resources Institute Climate Analysis Indicators Tool for 2013–19.

Note: The red segment in the first quintile represents China, which accounts for 37 percent of all emissions, 5 percent of the World Bank lending portfolio, and 2 percent of the IFC AS portfolio. AS = advisory services; EEPSCA = enabling environment for private sector climate action; IFC = International Finance Corporation.

Figure 2.6. Greenhouse Gas Emissions in Client Countries and EEPSCA Portfolio, by Country Income Group

Sources: Independent Evaluation Group team portfolio; emissions data from the World Resources Institute Climate Analysis Indicators Tool for 2013–19.

Note: The red segment represents China, which accounts for 37 percent of all emissions, 5 percent of the World Bank lending portfolio, and 2 percent of the IFC AS portfolio. AS = advisory services; EEPSCA = enabling environment for private sector climate action; GHG = greenhouse gas; IFC = International Finance Corporation.

The Bank Group has supported enabling environment for private sector climate change adaptation through disaster resilience, CSA, and water resource management. The World Bank has supported disaster resilience through actions, including strengthening of the public technical and institutional capacity for providing timely early-warning information to the private sector, and introduction of standards to improve the climate resilience of buildings or infrastructure. World Bank agriculture and water resources support has included provision of hydrological and meteorological information to farmers to help them adapt their practices to increasingly unpredictable rainfall and other climatic conditions, as well as supporting national agricultural research and extension systems to develop high-yielding climate-resilient crop varieties, and provision of financial incentives (such as payment for environmental service mechanisms for the adoption of climate-resilient land management or production techniques). For IFC, adaptation-related activities have mainly included support to regulators to assess and address the climate-related risks in the financial system and the development of insurance products against natural hazards.

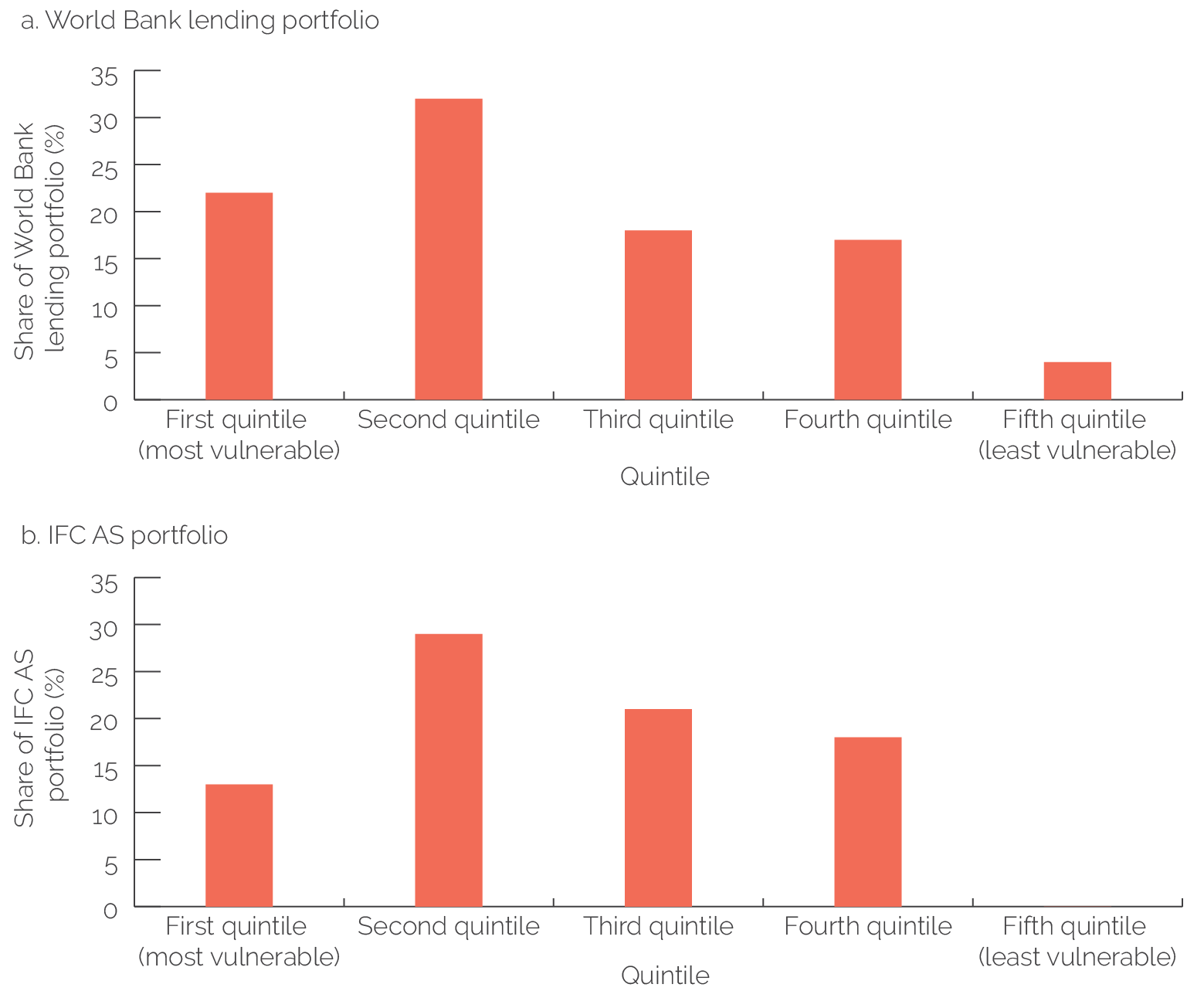

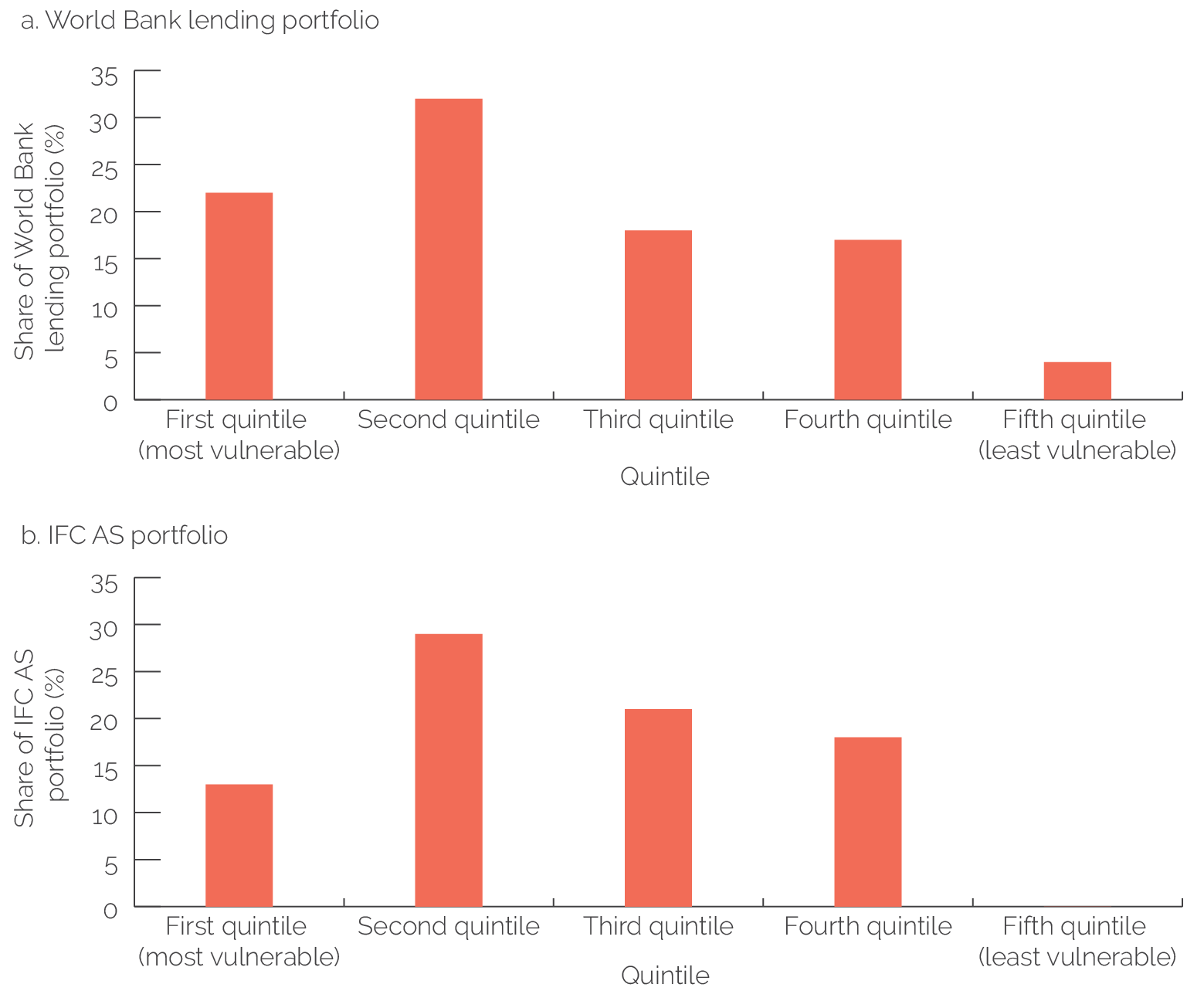

Countries with greater need for climate change adaptation receive only slightly more adaptation support compared with other countries. Figure 2.7 shows the Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative Country Index ranking for countries with the greatest vulnerability to climate change, organized into quintiles. If the Bank Group conducted activities with no consideration of need, then we would expect that, on average, each quintile of countries would receive about 20 percent of Bank Group support. However, if the Bank Group prioritized the countries with the greatest need, we would expect activities to be concentrated on the highest quintiles. The evaluation found only partial evidence of strategic prioritization. The quintile of countries with the greatest need for climate change adaptation receives 22 percent of World Bank EEPSCA projects and 13 percent of IFC EEPSCA AS; the top two quintiles together receive 54 percent of World Bank EEPSCA projects and 42 percent of IFC EEPSCA AS. Although some of the countries with the greatest need for adaptation are small states or countries experiencing fragility or conflict (where the private sector is relatively small and enabling environment activities may not be a priority), there were also no EEPSCA adaptation activities in highly vulnerable countries, such as Rwanda, Senegal, and Uganda. Highly vulnerable countries are also often low income, where private sector development is more challenging.

Figure 2.7. EEPSCA Adaptation Portfolio, by Climate Vulnerability Quintile

Source: Independent Evaluation Group, with adaptation needs from the Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative Country Index.

Note: AS = advisory services; EEPSCA = enabling environment for private sector climate action; IFC = International Finance Corporation.

- International Finance Corporation advisory services volumes have not increased by dollar amounts even as the number of activities remains flat. The evaluation analyzed the commitment volumes, measured as the total funds managed by the International Finance Corporation, for the International Finance Corporation advisory services enabling environment for private sector climate action portfolio, and found that the pattern was the same as for the number of projects.

- The Excellence in Design for Greater Efficiencies program is covered more substantially in the Independent Evaluation Group evaluation on demand-side energy efficiency (World Bank 2023c).

- The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (2022c) reports that among 71 countries that include the largest global emitters, there was no decline in the share of greenhouse gas emissions receiving fossil fuel subsidies between 2018 and 2021.

- See https://www.wri.org/data/cait-climate-data-explorer.

- See https://gain.nd.edu/our-work/country-index.