Confronting the Learning Crisis

Chapter 3 | The World Bank’s Approach to Basic Education and Learning Outcomes at the Country Level

Highlights

During fiscal years 2012–22, in the 91 countries in which the World Bank supported basic education, it supported a single operation in 38 countries (7 in the Africa Region) and two operations in 22 countries (10 in the Africa Region), excluding emergency COVID-19 operations. In 12 countries, it supported five or more operations. Countries with two to four operations have learning poverty rates ranging from 11 percent to 98 percent, which suggests that support for basic education projects may not always focus on the countries with the lowest outcomes.

World Bank analyses tend to address symptoms or parts of identified challenges without addressing the fundamental causes of education failure.

The World Bank typically supports similar inputs—government-level management, in-service teacher training, and school management—across most country types. The results of these inputs are measured by outputs rather than by changes in systems, improved teaching, or increased learning, missing a critical feedback loop to demonstrate whether the inputs are effective and contributing to learning. For example, monitoring and evaluation of improved learning outcomes are specified in one-third of project development objectives in the basic education portfolio, and only 22 out of 188 operations with on-the-job training tracked the impact of the training on teachers’ practices.

The causes of failure can involve stakeholders at levels other than central government. The World Bank typically focuses its attention at the higher level, giving it a comparative advantage in influencing education policy; however, lower levels of basic education systems, which must implement that policy, get less capacity-building support from the World Bank.

Reference to marginalized groups and the level of analytic focus on broader equity-related issues increased over the evaluation period in Country Partnership Frameworks and Systematic Country Diagnostics, as well as in Project Appraisal Documents, where there is also an increase in targeting of such groups.

Monitoring and reporting of results on a disaggregated basis predominantly focus on gender and not on other groups, which weakens the ability of policy makers to assess the adequacy of the response and to provide feedback for future policy and planning.

In responding to the challenges of COVID-19, the World Bank accelerated emergency financing through 80 operations (34 percent of the portfolio) to address schools reopening by supporting incentives and inclusion, school health and nutrition, information and communication technology, learning materials, and community participation for remote learning and for reopening schools.

This chapter examines World Bank country-level support for basic education. It draws on evidence generated from a portfolio review analysis and 10 case studies undertaken for the evaluation. It also draws on secondary data analysis and evidence from background papers that researched aspects of the literature on the political economy of education and the approach adopted by other development partners in their support for basic education. The chapter details World Bank financing and its basic education portfolio in the context of overall subsector financing and then analyzes key challenges identified by the World Bank and inputs provided in response. Findings are presented with reference to the evaluation framework set out in chapter 1, with specific focus on systems analysis, funding, teaching, measurement of learning, capacity across all levels of systems, equity, partnership, and political commitment—a necessary condition for more effective World Bank support.

Overall Financing for Basic Education

Before discussing the World Bank basic education portfolio, it is important to contextualize the broad shape of financing for education, including basic education. Between 2009 and 2019, governments contributed 82 percent to all expenditure on education, households contributed 17 percent,1 and development assistance accounted for 1 percent (World Bank and UNESCO 2021). Less than half (43 percent) of the development aid contribution to expenditure on education goes to basic education. Development assistance accounts for a greater part of expenditure on education (all levels) in low-income countries than in lower-middle-income countries. The main difference between high- and low-income countries in education investment, the Education Finance Watch 2021 found, stems from differences in the overall size of the public sector, rather than differences in how education is prioritized, and in the equity of its distribution (World Bank and UNESCO 2021). This is an important observation regarding the financing of education reform—a key element of the conceptual framework—showing that, broadly speaking, governments are prioritizing education spending. The Education Finance Watch 2022 found that, since the onset of the pandemic, overall bilateral aid to education had fallen (World Bank and UNESCO 2022), and the Global Education Monitoring Report estimates an annual financing gap of $97 billion during 2023–30 in 79 low- and lower-middle-income countries to achieve SDG 4 targets (UNESCO 2023)2

The World Bank Basic Education Portfolio

The World Bank is the single largest source of external financing for the education sector in low- and middle-income countries (World Bank 2023c), although funding for the sector—and for basic education—is a small part of its overall lending. For example, International Bank for Reconstruction and Development and International Development Association commitments to education in FY22, from preprimary to tertiary levels, represented just under 5 percent of all World Bank commitments. The World Bank (2022b) reports that 24 percent of the active portfolio ($23.6 billion) goes to primary education and a further 25 percent to secondary education (with no breakdown provided between lower and upper levels of secondary education). Extrapolating in the absence of series data, it is reasonable to conclude that primary education, the core of basic education, attracts about 1 percent of overall World Bank lending.3 Given the criticality and the scale and depth of the crisis in learning, the need to ensure strategic targeting of this limited resource is evident, and, as per the evaluation framework, strategic targeting can be achieved if based on a comprehensive systems-based analysis.

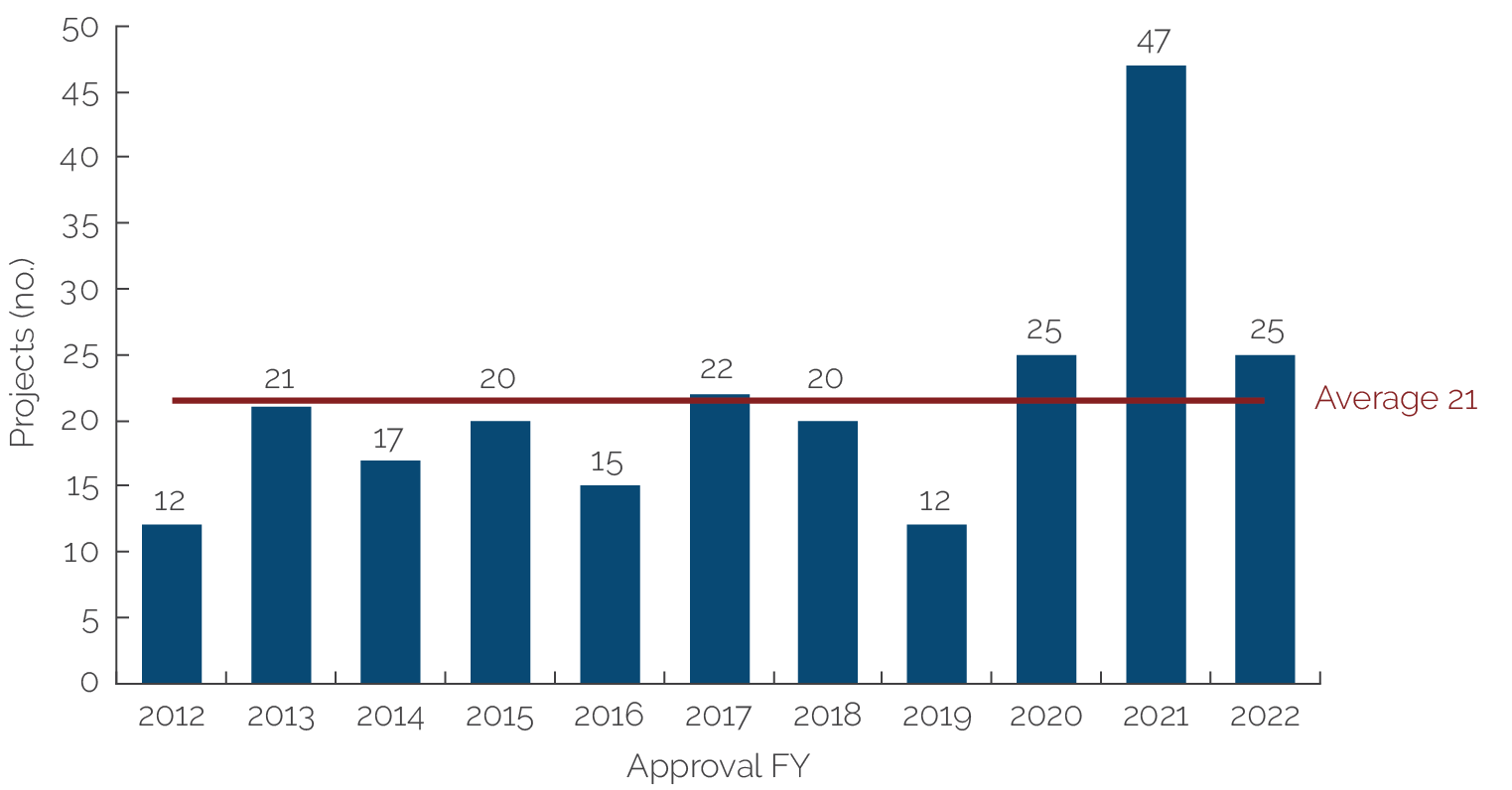

During FY12–22, the World Bank approved 236 basic education operations with a total commitment value of $25 billion. About 86 percent of those education operations (203 operations) are supported by investment project financing, with an average commitment of $83 million. In more recent years, the World Bank has introduced the Program-for-Results instrument, with 59 percent of the 29 Programs-for-Results in the portfolio approved since 2020. Case studies also found that disbursement-linked indicators had been introduced to investment project financing in Ethiopia, Kenya, Pakistan, and Sierra Leone as a precursor to the more outright results-based approach under Programs-for-Results. IEG found no differences between investment project financing and Programs-for-Results and the type of intervention and measurement.4 The portfolio featured only four development policy loans.5 The average project size across all instrument types, including support during the COVID-19 crisis, is $106 million, with significant variation in project volume, ranging from a minimum of $0.24 million to a maximum of $1,006 million. South Asia had the largest average of $215 million and median of $123 million, probably reflecting the larger populations in the countries supported, such as Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan. About 46 percent of all operations were approved in a four-year period (FY19–22), with a spike in FY21 (47 projects compared with an annual average of 21 over the entire evaluation period) at the height of the COVID-19 crisis (figure 3.1).

Figure 3.1. Basic Education Project Approval during Fiscal Years 2012–22

Source: Independent Evaluation Group portfolio review.

Note: FY = fiscal year.

The largest share of projects by number (44 percent) is in the Africa Region, followed by 16 percent in both the Latin America and the Caribbean and the South Asia Regions (figure 3.2). During the evaluation period, the number of education operations has increased in countries classified as fragile and conflict-affected situations, from 23 to 39. This increase is consistent with the World Bank’s priorities (fragile and conflict-affected situations strategy) and reflects support provided during the COVID-19 pandemic. The ratings of education sector operations have steadily risen, based on delivery of outputs, and are high relative to all World Bank operations (box 3.1).

Financing is one of the World Bank’s levers of influence in the education sector, particularly in lower-income countries. In Ethiopia, for example, the World Bank brought more resources and development partners into pooled funding support for the government’s program in a context characterized by a significant financing gap between the sector strategy goals and the available resources to address the growing demographic. In Viet Nam, a rapidly developing lower-middle-income country, by contrast, the World Bank’s financing offers less leverage, although it does provide “a seat at the table,” which the World Bank has been able to use to help support the introduction of innovations from other contexts. This has included the introduction of curriculum and pedagogical changes to promote critical thinking and support for equity in education.

Box 3.1. The Project Ratings System

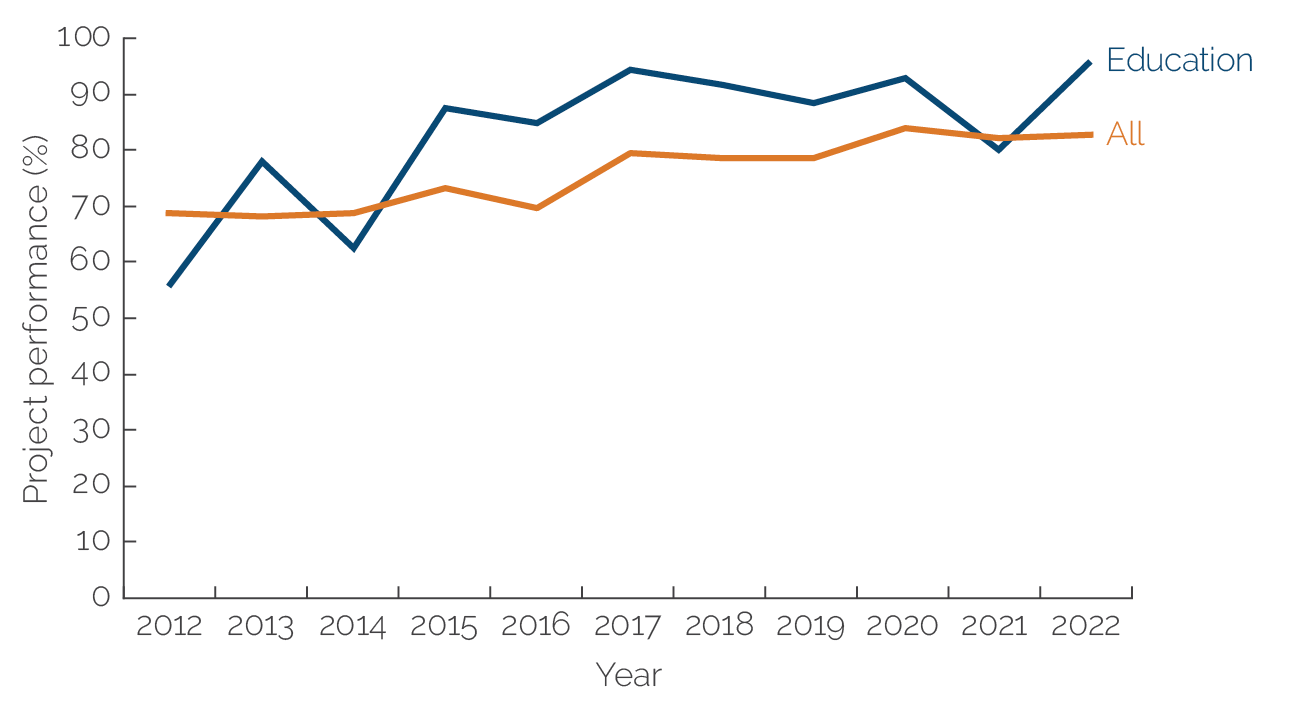

Education sector projects—inclusive of projects spanning early childhood development to tertiary education—have been among the best performing of all World Bank projects (figure B3.1.1). Under its agreement with the World Bank, the Independent Evaluation Group uses an objectives-based approach to rating or validating the self-evaluation of projects undertaken by the World Bank itself. A key rating criterion is the level to which a project has achieved its objectives. However, the achievement of objectives set for World Bank projects in the education sector is typically defined and measured by outputs, such as number of schools built or number of teachers trained, and not by learning outcomes.

Figure B3.1.1. Performance of Education Sector Projects Relative to All Other World Bank Projects

Source: Independent Evaluation Group Implementation Completion and Results Report database.

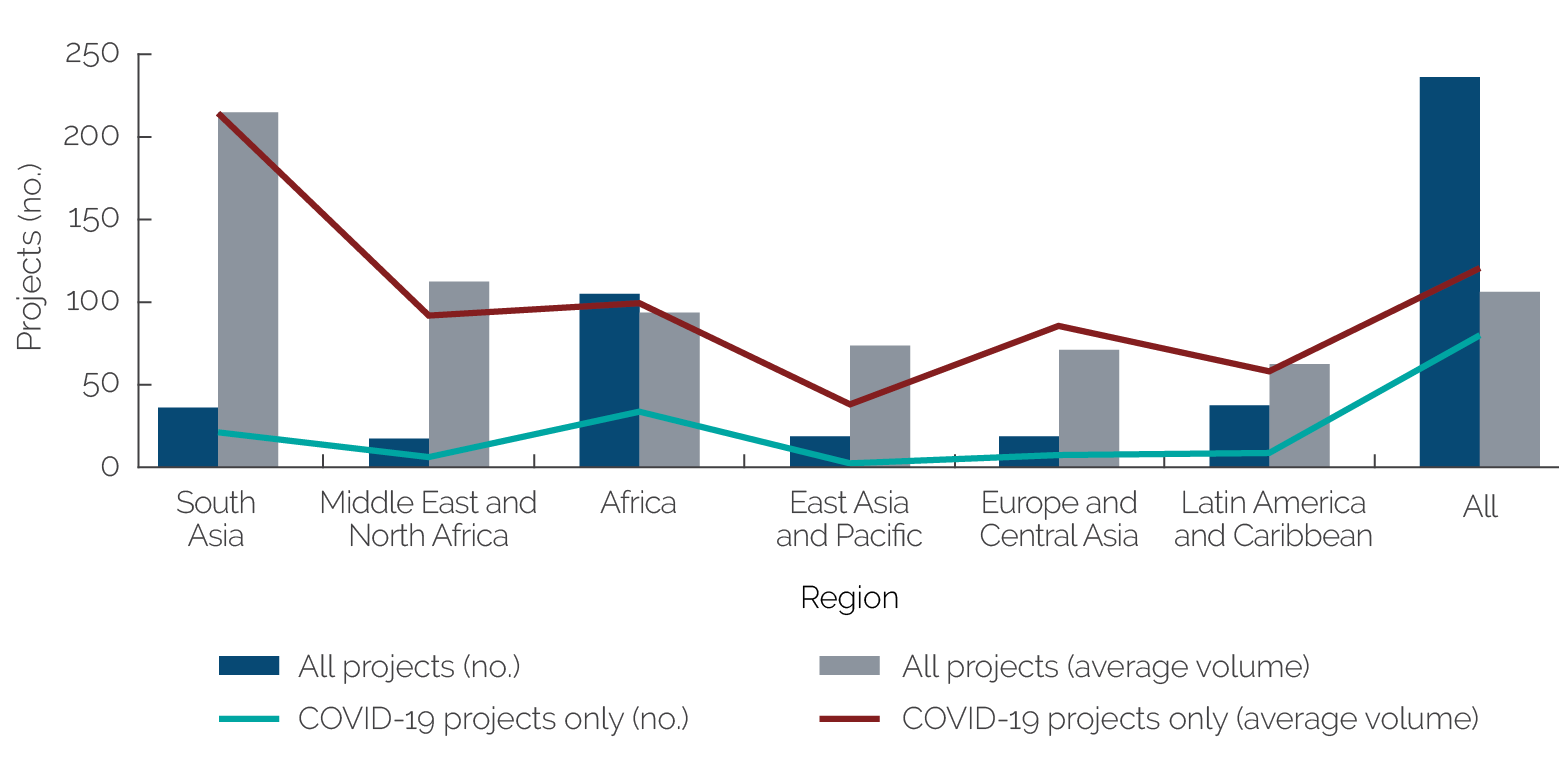

The basic education portfolio includes 80 operations (34 percent) that in whole or in part address the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on basic education systems.6 The emergency funding was provided to 48 countries. The average volume for the 80 projects is $121 million, which is greater than the overall average project volume across the evaluation period. The majority of projects in the South Asia Region (n = 21; 57 percent) responded to the COVID-19 crisis (figure 3.2). In the Africa Region, 34 projects (32 percent of projects in the Region) responded to the crisis.

Source: Independent Evaluation Group portfolio review.

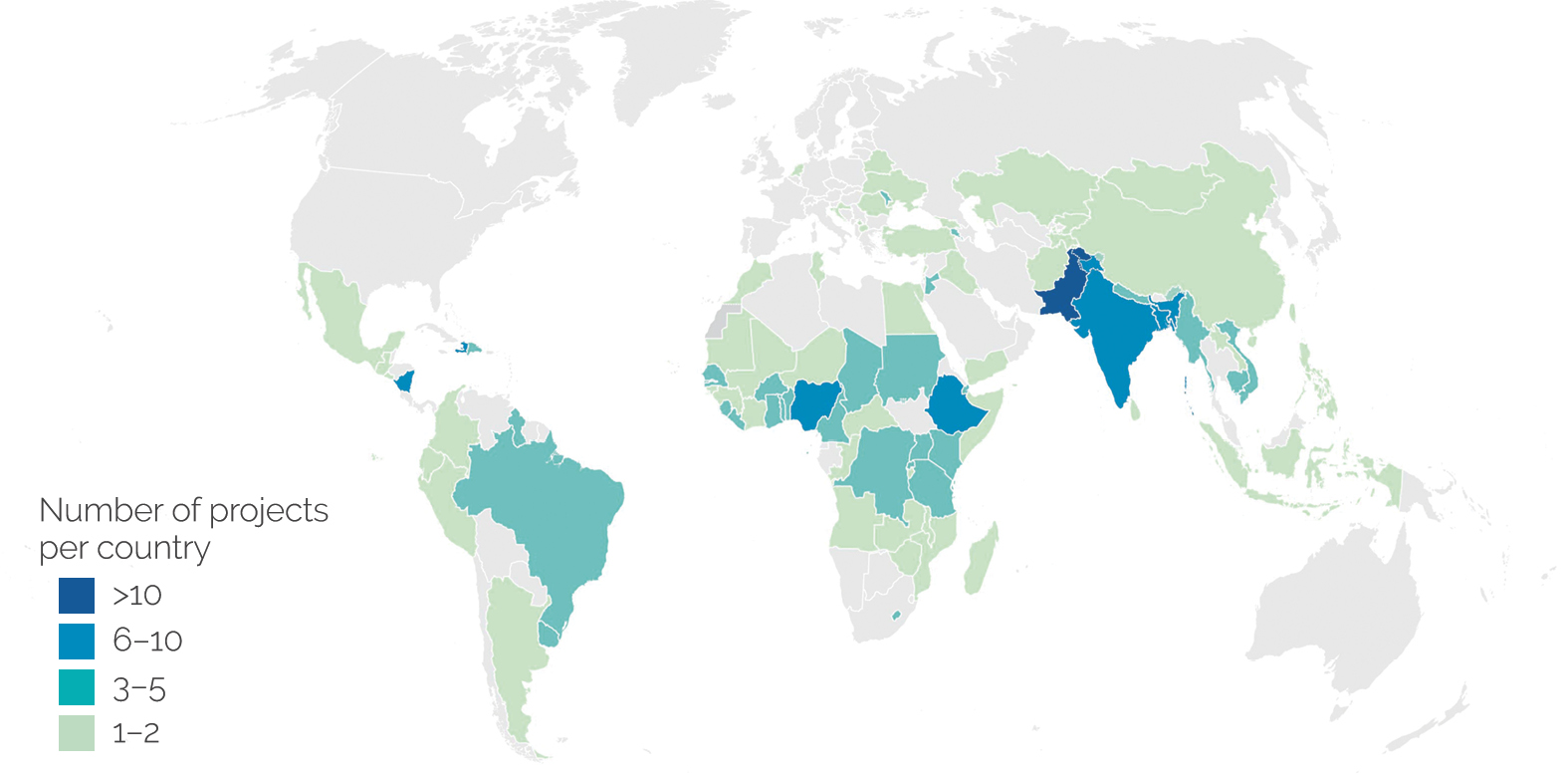

The evaluation found that, in many countries, World Bank support for basic education lacks intensity and continuity in the face of what, as detailed in the evaluation framework, is a particularly complex problem. World Bank support was limited to one or two projects during FY12–22 in more than half of the 91 countries in which it provided basic education support (figure 3.3).7 Excluding COVID-19–specific support, World Bank support for basic education consisted of a single operation in 38 countries and two operations in 22 countries. In a further 11 countries, support for basic education consisted of a single COVID-19 emergency response operation—that is, the World Bank was not otherwise supporting basic education reform in those countries during the evaluation period.8 Countries supported by a single operation were in all Regions, including 7 countries in Africa (Burundi, Cabo Verde, the Republic of Congo, Guinea, Mozambique, Somalia, and Zimbabwe). Among the countries that had two operations during the evaluation period 9 were 10 countries in the Africa Region, where the crisis in learning is concentrated.10 Twenty countries (22 percent) had four or more operations in support of basic education during FY12–20. In 12 of these countries,11 five or more operations were supported. Countries with two to four operations had moderate to high learning poverty rates, ranging from 11 percent to 98 percent. Overall, and notwithstanding competing priorities, lending limits, and other influencing factors, the relative lack of concentration on basic education suggests that support may not always focus on the countries with the lowest outcomes.12

Source: Independent Evaluation Group portfolio review.

Note: Color coding represents the number of projects, excluding COVID-19 operations, for fiscal years 2012–22. This map has been cleared by the World Bank Group cartography unit (IBRD48078; July 30, 2024).

World Bank Analysis toward Learning for All at the Country Level

The framework for this evaluation emphasizes the need for a comprehensive analysis of basic education systems to correctly orient interventions in favor of reform. The analysis needs to look across the system and to take into account, for example, the political economy of basic education and the perspectives and positions of key stakeholders. It also needs to be both technically sound and contextually sensitive so that the design of interventions can lead to durable change and desired outcomes.

The evaluation found that World Bank analysis of specific aspects of basic education systems—what is or is not working—is technically sound but typically does not sufficiently grapple with why education systems continue to fail children. Analysis of the adequacy of specific elements, such as data systems, financing, and teaching quality, helps to identify specific components that may be working or not working and provides a foundation for specific interventions. Such analysis may miss the idiosyncratic nature of basic education systems that respond to the unique mix of political, social, cultural, religious, and other factors that shape such systems. TTLs interviewed for this evaluation claim to be tacitly aware of these nuances. Institutional imperatives, such as the rotation of international TTLs every three to four years, may limit the extent to which it is possible to develop and maintain a deep understanding of context. Both formal and informal mechanisms are required to exchange, document, and curate tacit knowledge regarding the political economy and underlying drivers of education system performance.

The case studies identified a need for engagement to be contextualized to address political economy barriers, consistent with the evaluation framework. For example, case studies found that the World Bank predominantly engaged with central government actors, or in Brazil and Pakistan also with state and provincial government, and with development partners. Such an approach neglects the possible impacts of dynamic interaction among multiple, potentially powerful stakeholders—local administration, teachers and trade unions, parents, nongovernmental organizations, and civil society organizations. These parties can affect the achievement of desired outcomes or the alignment and capacity of the basic education delivery system, especially the actors in the lower levels of the system on whom fidelity to policy reform and implementation success depends. Analysis of documentation at the country level suggests that a more uniform, less nuanced approach is taken in the provision of support to basic education; see the analysis of challenges identified in Project Appraisal Documents (PADs) and World Bank inputs in this chapter.

The focus of project analysis and country documents has not changed during the evaluation period, notwithstanding publication of the WDR 2018 and its advocacy of a more systems-based approach. Across the period, the key challenges identified in the basic education portfolio are weak learning outcomes; learning inequity; inadequate teaching quality; and weak governance, accountability, and institutional oversight (table 3.1).13 For fragile and conflict-affected countries, learning inequity was a slightly higher concern (85 percent), whereas the other challenges were consistent with the overall pattern. Two additional challenges are emphasized for the Africa Region (and with countries affected by fragility, conflict, and violence)—inadequate learning environment and low educational attainment—suggesting deeper challenges at a more basic level in relevant education systems (that is, with matters such as levels of enrollment versus the adequacy of basic infrastructure, or numbers of teachers).

Table 3.1. Challenges of Most Concern in Project Appraisal Documents

|

Challenges |

2012–17 |

2018–22 |

||

|

Rank |

Incidence (%) |

Rank |

Incidence (%) |

|

|

Weak learning outcomes |

1 |

81 |

2 |

78 |

|

Learning inequity |

2 |

78 |

1 |

81 |

|

Inadequate teaching quality |

3 |

74 |

3 |

62 |

|

Weak education system: governance, accountability, and institutional oversight |

4 |

69 |

3 |

62 |

Source: Independent Evaluation Group portfolio analysis.

Failure to use systems-based analysis to give attention to the unique political economy and supporting conditions can have negative effects on the efficacy of World Bank operations. As the WDR 2018 argues, understanding the political economy is necessary to address the reasons education systems fail children. The World Bank has supported a comprehensive set of interventions during FY12–22, but these interventions encountered systemic challenges related to motivation, human resource capacity, adequacy of financial resources, and need for deeper coordination across all levels of the education system, as the Ethiopia case shows (box 3.2). The case studies identified instances where the World Bank had not anticipated government pushback. For example, in Viet Nam, a high-profile program was dropped in one instance and there were delays to a critical teacher training program in another. In Chad, the World Bank did not adequately appreciate low capacity at the central level, which resulted in the nondeployment of newly qualified teachers because there was no budget to recruit teachers trained under a project supported by the World Bank.

Box 3.2. Ethiopia: What Is Not Going Well and Why

The government of Ethiopia is constitutionally and legally committed to maintaining the integrity and capacity of education administration down to the woreda (district) level. The World Bank’s analysis finds key impediments to that mandate, such as feedback mechanisms that do not adequately inform policy makers of what works and what does not, inadequate capacity of internal audit systems and procurement, and inadequate capacity at decentralized levels. Regional governments decide how much of the region’s budget is allocated to education and transferred to each woreda, resulting in regional variability in unit costs. Moreover, public spending on a per-pupil basis favors tertiary education, which serves 3 percent of students, whereas per-pupil spending at earlier-grade bands is low, given that those grades serve 63 percent of students. Other sector challenges include teacher qualifications, dropout rates among students from poor families, and a large share of out-of-school children and youth (approximately one-third). Ethiopia’s large and rapidly growing school-age population exacerbates all these challenges, despite the government allocating 22 percent of its public funding to education.

Despite the sound analysis and identification of specific challenges (answering what the problem is) and the comprehensive set of interventions supported by the World Bank during the decade, interventions have encountered systemic challenges that show why one-dimensional fixes do not work. For example, women teachers were trained to become school leaders, but hiring them and sustaining them as principals (or vice-principals) ran into difficulties: civil service regulations requiring open competition for positions, cultural norms in regions unfamiliar with women in leadership roles, and a work burden that is more demanding than teaching (without a commensurate salary). Other challenges arose for the licensing of teachers and school leaders, which was implemented by testing new and existing teachers to assess their performance and by creating accreditation standards for teacher education institutes and a teacher licensing information system for collecting, managing, and analyzing licensing data. In that instance, the effort was challenged by the lack of incentives for teachers and school leaders to undergo licensing tests because the licensing results were not linked to their career development, suggesting that understanding teacher motivation at the outset was needed.

The analysis of interviews, documents, and reports suggests that some answers may be related to motivation, human resource capacity, adequacy of financial resources, and need for deeper coordination across all levels of the education system. Resource allocation within the sector and resource coordination between the federal government and regions remain an issue because regions are not required to allocate resources to education, as suggested by the Ministry of Education. Project Implementation Completion and Results Reports consistently noted human resource challenges that affected implementation. Despite training and capacity-building efforts, high staff turnover was related to government remuneration, which is capped at low levels.

Source: Independent Evaluation Group analysis of World Bank documents and interviews.

Effective Support for Policy Reform toward Learning for All

Where the World Bank has a willing and committed partner, it has been able to better focus on key policy reforms and to lay foundations for a learning-oriented system. Allowing for difference in context and the modality of implementation, leading education systems in the developed world, such as in Finland and the Republic of Korea, pay particular attention to key facets of basic education systems, including teaching and career progression, measurement of learning, financing to achieve equity of learning, and meritocracy in hiring at all levels of the system. Where countries are in tune with, or at least in deliberate, sustained pursuit of these conditions, World Bank support is most effective.

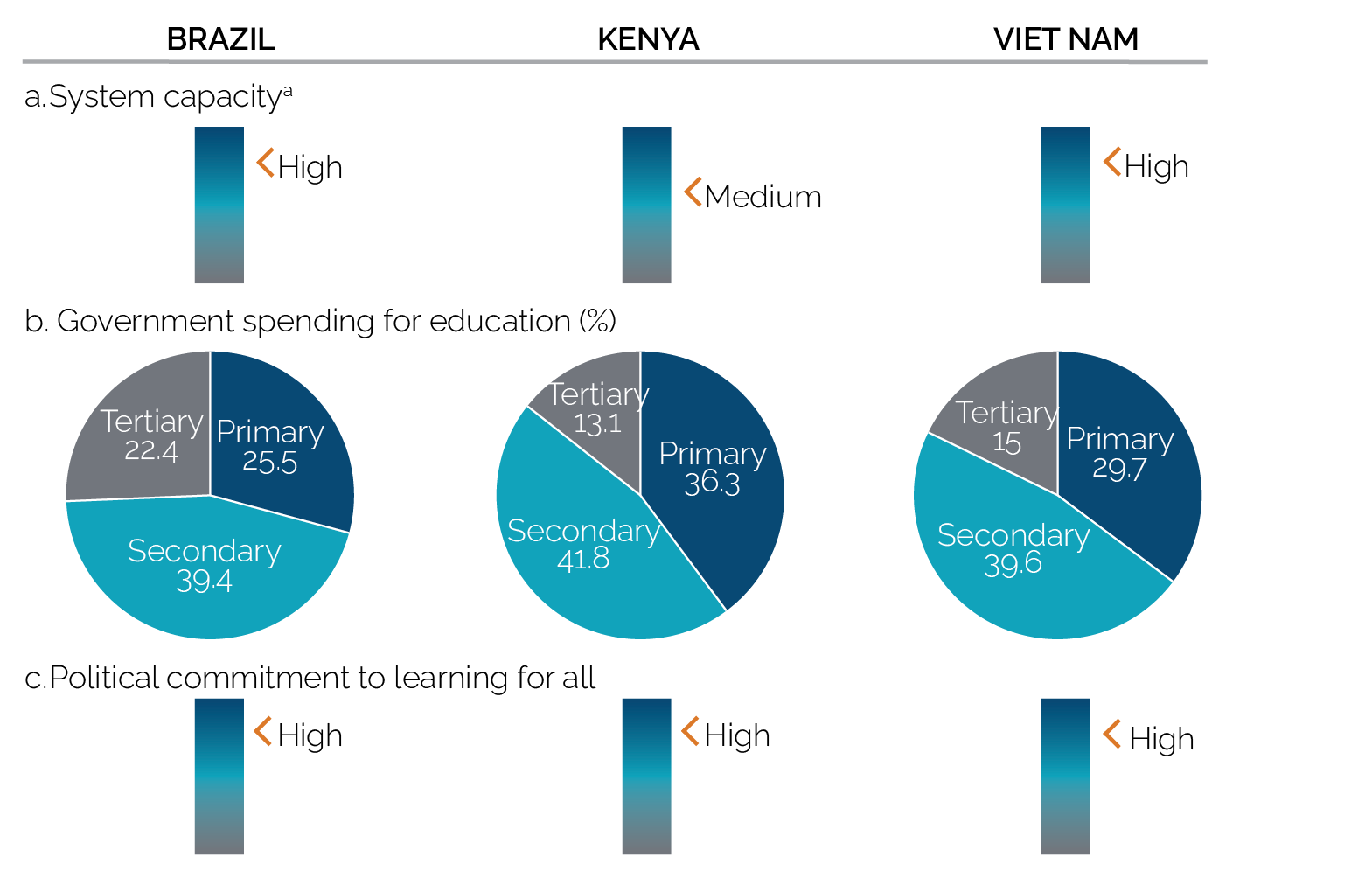

Brazil, Kenya, and Viet Nam have significant differences in political structure, culture, basic education systems, and many other characteristics; however, in all cases, they have strong political and financial commitment in support of learning for all combined with a strong equity focus (figure 3.4). Across these countries, political commitment goes beyond rhetorical statements in the media and sector strategies. Commitment is evident with clear implementation actions to improve quality and learning—even in systems with growing demographics. It is also evident in political commitment to communicate learning data and establish clear goals for learning improvement. Brazil, Kenya, and Viet Nam have also made their political commitment apparent by allocating financial resources to prioritize primary and foundational learning, consistent with leading education systems. The evaluation found that in those contexts, the World Bank has been able to deploy its resources—knowledge, technical assistance, policy dialogue, and financing—more effectively in support of reforms that contribute to improvement in learning outcomes, consistent with aspects emphasized by leading education systems. In these countries, the World Bank intervened subject to context and across the leverage points included in the conceptual framework for this evaluation—during planning, implementation, and monitoring—based on where the country was in relation to reform efforts in pursuit of learning for all. Aspects of the World Bank’s analysis of context and engagement could have been strengthened in each case, but the examples illustrate broad understanding of context and leverage points in support of more effective system reform.

Sustained funding by the government and its partners, including the World Bank, and high parental expectations and high social value for education were key to successful basic education reform in Viet Nam. The reform effort was buoyed by sustained investment from a growing economy, including significant investment in administrative and teaching capacity, with financing for foundational learning and basic education as a priority.14 As part of its planning, the government requested and absorbed the World Bank’s comprehensive analytic support, which addressed the quality, economics, and equity of education. World Bank research and evaluation, as well as support for student assessments since the early 2000s, were key to defining needs and monitoring progress.

World Bank operational support shifted with government needs, from interventions focused on specific features of school quality (Viet Nam Escuela Nueva and School Education Quality Assurance Program) toward more comprehensive national curriculum and teacher training projects (Enhancing Teacher Education Program and Renovation of General Education Project). The latter supported competency-based learning, recognizing that Viet Nam’s education system had achieved most of its goals for foundational learning and basic skills. The competency-based curriculum places heavy demands on teachers; therefore, the emphasis is on teacher professional development—work that remains in progress.

The government also sustained, with World Bank support, a focus on equity in education. Ethnic minorities were a major focus in projects, reflected in the choice of provinces and schools in the School Education Quality Assurance Program and Viet Nam Escuela Nueva and in implementation arrangements for training, textbooks, and monitoring in the full-scale projects (Enhancing Teacher Education Program and Renovation of General Education Project). Attention to rural poor people was less pronounced, but World Bank programming clearly recognized the extra challenges in project implementation in rural areas and schools. Children with disabilities also received less attention in general in World Bank projects, with one exception—Quality Improvement of Primary Education for Deaf Children.

Figure 3.4. Levels of Financial and Political Commitment to Learning for All in Brazil, Kenya, and Viet Nam

Source: Independent Evaluation Group case studies.

Note: a. Capacity was measured using percentiles among Country Policy and Institutional Assessment data.

Although broadly successful, the World Bank’s program of support in Viet Nam faced political challenges. An envisaged scaling up of Viet Nam Escuela Nueva was not achieved, despite technical implementation that was largely successful, because of resistance to change among some parents and teachers, and the voluntary expansion beyond project targets encountered issues due to lack of resources. Political pushback also led to delay and eventual cancellation of key features of the Renovation of General Education Project curriculum and textbook reform project and to challenges with the in-service teacher training program (Enhancing Teacher Education Program).

In the years before the COVID-19 pandemic, the government of Kenya embarked on ambitious reforms that sought to improve the quality of education through several approaches: a competency-based curriculum, reforming of professional teacher development, textbook policy, and management practices at the local level. Learning outcomes have been variable since 2016, with significant challenges remaining, particularly in rural areas, but overall the country ranks as a top performer in Eastern and Southern Africa. In this case, the World Bank had little influence in basic education during the early years of the evaluation period because of a strained relationship associated with a failed sectorwide approach. During the evaluation period, the World Bank regained and leveraged its influence through (i) ongoing contact with the government, despite the lending hiatus; (ii) renewed lending with GPE support; and (iii) development of a close working relationship with the government in support of strategy and planning.15

Since recommencement of financial support in 2015, continuous support and a high level of engagement have ensured a high level of World Bank influence. After initially using GPE funding to formally reengage with the basic education subsector, the World Bank has since positioned itself at the heart of basic education reform in Kenya with a continuous, connected string of projects (Primary Education Development Project, Secondary Education Quality Improvement Project, COVID-19 Learning Continuity in Basic Education Project, Primary Education Equity in Learning Program, and future operations already being planned). This level of engagement has allowed the World Bank to occupy a sustained, influential position in policy making for basic education. The World Bank also worked with the government toward a more inclusive, quality-driven education system, taking a systemic perspective in working to enhance the capacity and standing of the ministry and key agencies.16 For example, the World Bank supported training of staff in the psychometric department of the Kenya National Examinations Council in specific technical skills to enable them to improve learning assessment instruments and to provide more informed advice to the ministry on Kenya’s participation in international assessments.

Sustained effort was also key to advances in data collection in Brazil, where successive governments supported the most disadvantaged individuals and regions over two decades through measures such as Bolsa Família and the Fund for Maintenance and Development of Basic Education. Brazil has a long history of investing in indicators and monitoring systems, including the Basic Education Assessment System and the national education quality index. These initiatives, with support from the World Bank, have provided valuable measures of learning outcomes, promoting evaluation of the effectiveness of schooling and informing better policies and practices. The data and monitoring systems compare well with those of many developed countries and have been augmented by many related initiatives at state and municipality levels (OECD 2021).

The World Bank contribution started before the evaluation period, with dialogue and technical assistance to support the development of outcome measurement and with help to equalize federal financial allocations, taking equity into account. During the evaluation period, the World Bank worked with the state of Ceará on results-based management mechanisms, providing technical support that contributed significantly to improving governance, accountability, institutional capacity, school management, and meritocracy. In Ceará, the World Bank supported the research institute Instituto de Pesquisa e Estratégia Econômica do Ceará to develop an innovative and context-specific, results-based management reform to incentivize mayors to improve the quality of basic education. This contributed to substantial system improvement and alignment of implementation between the central and lower levels of government because results-based management mechanisms are now shaping monetary transfers from the federal level to the states and from the states to the municipalities, contingent on achieving predefined learning outcomes. The analysis of binding constraints was used to define areas supported by the operation—length of school day, inadequate teacher quality, and age-grade distortion. The analysis recognized that race, gender, geography, and socioeconomic status affect the probability of accessing quality education, but it did not elaborate on the causes, implications, and possible solutions to effectively support students in these groups. Instead, efforts to improve learning have focused on students lagging behind their age-group, regardless of other characteristics that may affect learning outcomes.

The World Bank’s analyses in Brazil, recognizing the importance of political context, show a thorough understanding of the governmental actors at the national and state levels in the education system and the perspectives of private companies and employers. The analysis could have been further enhanced with attention to how the role of municipal political actors, school managers and teachers, students, parents, and their communities are aligned to the goal of improving education quality. What distinguishes these examples is that the aim is not delivery of an intervention or inputs into the system but a clear focus on system reforms toward learning.

The above examples illustrate attention to some of the critical aspects of the system—measurement of learning, teaching, equity, and system coherence and capacity. Given the limited consensus about what works to improve learning (Evans and Popova 2016), a feedback loop is essential to inform intervention choices, as depicted in the evaluation framework. This means consistent examination of whether the interventions and inputs the World Bank finances are having a positive impact on systems, teaching, and measurement of learning. As discussed in this chapter, patterns across the portfolio and case studies reveal that World Bank interventions predominantly support activities and monitor outputs (see figure 1.2), rather than seeking incremental reform of aspects of the education system and monitoring changes in teaching, learning, and systems.

World Bank Inputs and Responses to Address Learning for All at the Country Level

This section discusses World Bank inputs in support of basic education and learning for all at the country level, largely based on analysis of country need. It details knowledge inputs and the types of inputs financed by World Bank operations and then looks in detail at particular aspects of the response related to capacity building, equity, partnership, and other factors.

Knowledge Input at the Country Level

The volume of country-level advisory and analytic World Bank support that focuses on quality basic education, the crisis in learning, or inclusion is limited. Among the 10 case countries, IEG identified 68 education-related pieces approved between FY12 and FY22. This consisted of 34 ASA products, of which less than half across the 10 cases over 10 years more directly addressed basic education and matters related to quality and inclusion, such as work on learning (Ethiopia, Pakistan, and Viet Nam), teachers (Kenya, Sierra Leone, and Tajikistan), refugees (Ethiopia and Kenya), and service delivery (Chad and Pakistan). The remainder of the ASA projects (29) typically covered broad policy areas—human capital, workforce education, education public expenditure review—within which basic education is relevant but not the featured component. Other country-level analytic and advisory activities included technical assistance (15), such as consultancy support for the development of the education sector strategy in Sierra Leone and workforce development in Viet Nam, as well as economic and sector work (14) that covered subjects ranging from human development (Nepal) to science, technology, and innovation (Viet Nam) and an education sector review (Pakistan).

Types of Input Supported by World Bank Operations

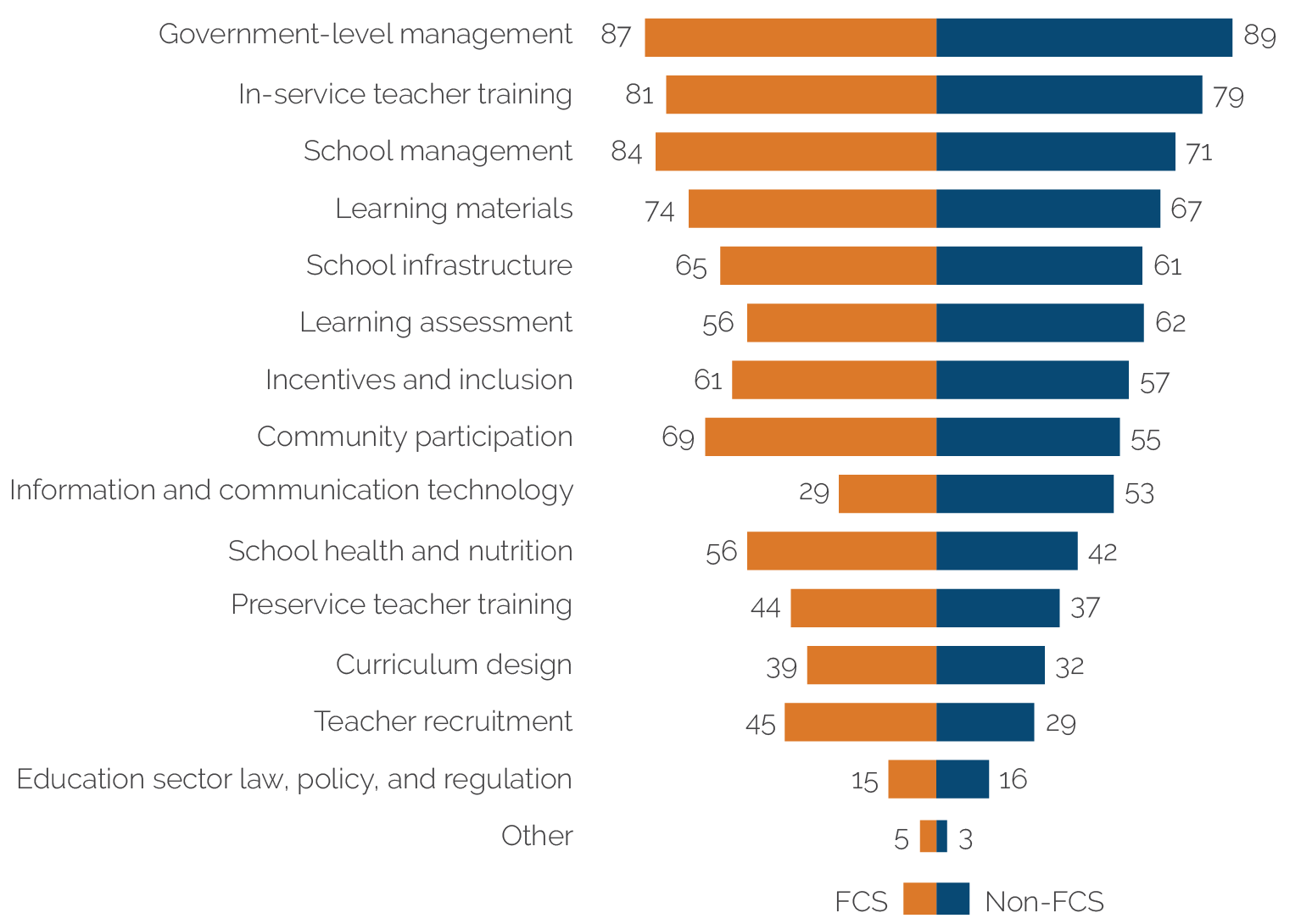

In response to its analysis of education sectors and client demand, the World Bank supports similar inputs across most country types.17 The most regularly supported inputs are government-level management, in-service teacher training, and school management, which are supported across the portfolio in 88 percent, 80 percent, and 75 percent of projects, respectively.18 This level of concentration in the portfolio and similar observations in case studies suggest a lack of nuanced response to the differing contexts and basic education systems within which the World Bank works.19 The World Bank also supported other inputs, such as learning materials (69 percent), school infrastructure (62 percent), learning assessment (61 percent), and information and communication technology (47 percent), with support for the latter increasing, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic. In the Africa Region, there was added emphasis on school health and nutrition (found in 61 percent of operations, compared with 34 percent across other Regions), which is one of the few interventions consistently shown to have positive effects on learning in most contexts (Snilstveit et al. 2015). In countries classified as fragile and conflict-affected situations, slightly more attention is paid to school management, learning materials, community participation, school health and nutrition, preservice teaching, and teacher recruitment, and less attention is paid to learning assessments and information and communication technology than in non-fragile and conflict-affected situations (figure 3.5).

Figure 3.5. World Bank Project Support of Inputs in Areas Related to Basic Education (percent)

Source: Independent Evaluation Group portfolio analysis.

Note: FCS = fragile and conflict-affected situation.

Support for Capacity Development

World Bank engagement at the central level puts it in a strong position to influence policy development—a key initial component of the evaluation framework. Case studies found that the relationship with central government—ministries and key agencies (such as those involved in curriculum or assessment)—represents a comparative advantage in that it allows for access to policy makers and for influencing the broad trajectory of education policy. As figure 3.5 shows, management training, with an emphasis on central government, has been the most common input in World Bank projects over the evaluation period. However, despite the close relationship that the World Bank typically has with central governments, partners told IEG that the World Bank was less likely to “push” governments on more progressive reform. TTLs referred to the balance that must be struck between access to decision makers and the extent to which policy can be challenged.

The World Bank’s relative lack of focus on lower levels of basic education systems has negative implications for policy implementation—an aspect highlighted in the evaluation framework (table 3.2). Management training supported by the World Bank includes significant levels of management training for central government officials. Frequent areas of support across case studies at the central level include EMIS and data, teacher training and curriculum, and student assessment capacity in countries supported by the READ trust fund (Ethiopia, Tajikistan, and Viet Nam). At lower levels of basic education systems, inputs are frequently designed to ensure effective delivery of projects—for example, training in financial management and procurement. Capacity developed in that context is relevant to effective project delivery of outputs and project monitoring but not always transferable to how things are done in the environment or context beyond the project.

The negative effects on enhanced learning outcomes associated with capacity constraints at lower levels of basic education systems were consistently cited in World Bank documentation, PADs, and interviews with stakeholder groups. For example, in the case of Nepal, interviewees recognized the many stakeholders in basic education, particularly given the decentralized approach that is being rolled out and the capacity challenges this raises. The World Bank (and other donors) has provided some support for the development of local government capacity, but that support is not comprehensive or sustained. The FY23–28 Country Partnership Framework (CPF) for Kenya identifies “acute capacity constraints at the local level, ambiguities in financing arrangements, and weak vertical coordination” (World Bank 2022a, 12) and sets out to target its support where institutional and implementation capacity is most needed—that is, in relation to equity in learning outcomes rather than primary enrollment (noting that education is not a CPF priority).20 Interviewees in Kenya reported that inequitable distribution of available resources to the local level reinforces disadvantages and capacity imbalances between counties and observed that although Kenya has well-developed policies, the core challenge is more about the practice and quality of implementation. Interviewees also noted that in many countries, a high proportion of public expenditure goes to education; however, because GDP is low, that level of expenditure is insufficient to support reform and inclusion—that is, expenditure is dominated by recurring costs (salaries), and what is available to support the development of capacity at lower levels of the system is negligible. One senior World Bank interviewee referred to enduring gaps in capacity as one of the great failures of the collective development community, stating that “every project tries to do capacity building, which usually involves studies or bringing in technical support or monitoring and evaluation [but does not] actually do the detailed analysis of how institutions function and what is the political economy. We find out during implementation and try to fix them as we go along.”

Table 3.2. Capacity Building in Some Case Study Countries and Associated Results

|

Case Study |

Capacity Building for Central Level |

Capacity Building for State, Province, or Lower Levels |

Results |

|

Brazil |

ASA and dialogue related to learning outcomes, racial equity, female empowerment, teacher training, results-based management; technical assistance on data to develop evidence-based policies. |

Project design and implementation support; technical assistance with development of a variety of outcome and process indicators to monitor state sector performance. |

State sector performance monitoring contributed to better coordination and accountability between system levels. |

|

Iraq |

Knowledge sharing, workshop, and technical support to ministry relating to the Iraq National Education Strategy. |

In the Kurdistan regional government, capacity building related to student learning assessment and private sector engagement. |

Not yet assessed. |

|

Nepal |

Support for governance, fiduciary management, and technical assistance to, in turn, support data systems, reinforced via disbursement-linked indicators. |

Local government institutional capacity via disbursement-linked indicators (that is, integrating education sector plan activities into annual work plan, budget, and EMIS policy guidelines with clearly defined roles and responsibilities at various levels of government and schools; providing ownership and role to local governments in the implementation of pro-poor targeted scholarships and proscience scholarships). |

Not yet assessed. |

|

Tajikistan |

Technical assistance to the National Testing Center on formative assessments and for country-level student learning outcome data. Technical assistance for EMIS to contain a more comprehensive database, including aggregate fiscal statistics, demographic indicators, and key macroeconomic variables, and to cover other levels of education. |

— |

Technical assistance to the National Testing Center was halted by World Bank before capacity was fully realized. The Agency on Statistics, under the president of Tajikistan, adopted the EMIS-based indicator and reporting framework, allowing the Ministry of Education and local education groups to identify gaps and determine future priorities. |

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: ASA = advisory services and analytics; EMIS = education management information systems.

Support for Equity

World Bank analysis of the basic education sector in its country clients over the evaluation period shows an increasing level of focus on equity-related issues—an important aspect of the evaluation framework. Country strategies, Systematic Country Diagnostics, and PADs demonstrate sound analysis of barriers to participation and learning related to poverty and gender throughout the evaluation period. The portfolio review analysis and case studies suggest that more recent analysis demonstrates increased attention paid to barriers associated with disability, ethnicity, and displacement.

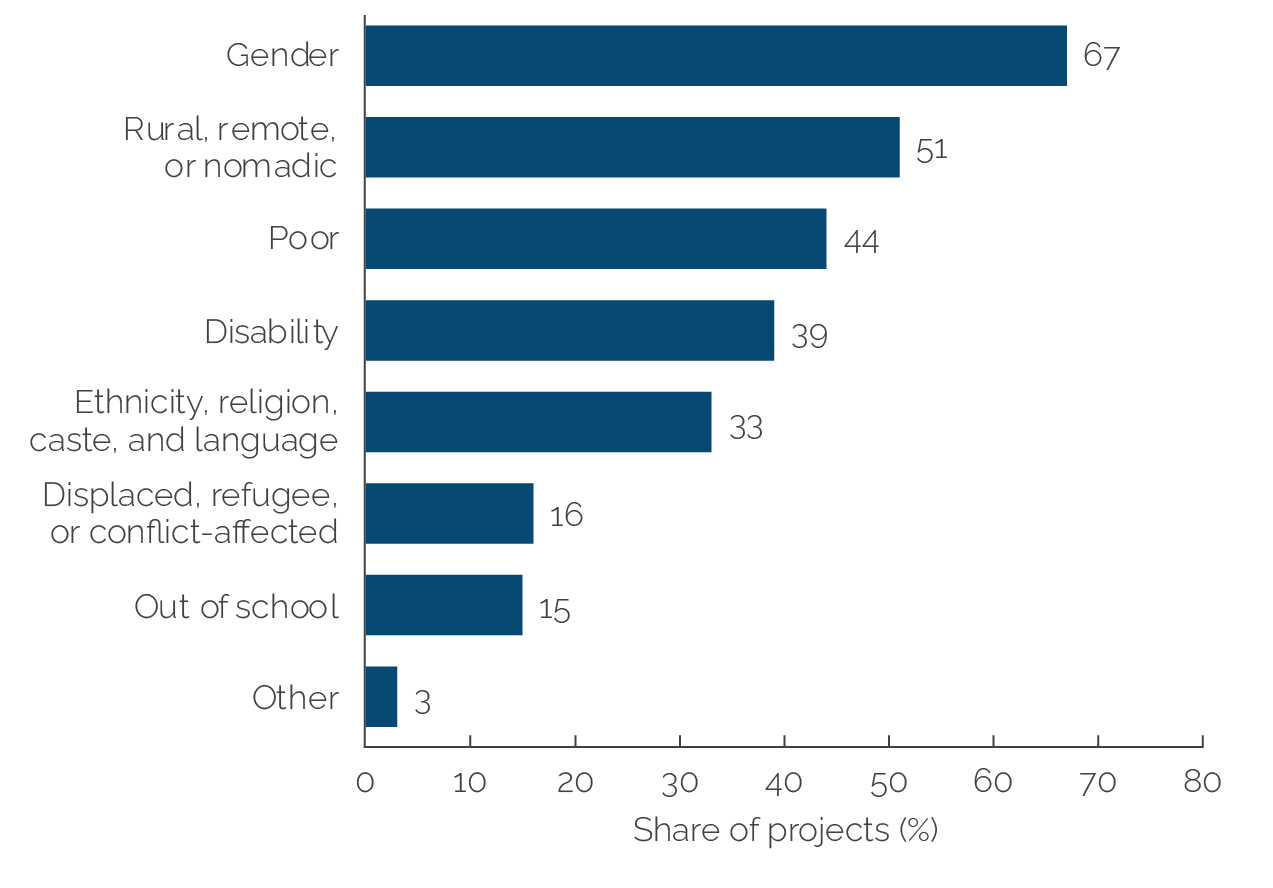

Almost all World Bank projects seek to address equity-related issues and reference various target groups, with a particular emphasis on gender equity. The portfolio review examined project activities and beneficiaries, finding that nearly all (93 percent) identified specific target group(s). Gender-targeted activities, almost uniformly treated with reference to girls, were supported in 67 percent of all projects, with an even higher rate among projects in Africa (82 percent). In addition, the disruption of education systems by the COVID-19 pandemic brought about a renewed or reinforced focus on girls, who, in many cases, were considered less likely to return to school because of pregnancy, early marriage, or other cultural barriers. More recent thinking, including in the World Bank gender strategy for FY16–23,21 recognizes that “weaker learning outcomes and educational achievement may be a limiting factor for boys and young men” (World Bank 2015, 36), suggesting the need for a more nuanced and contextualized approach to gender than is evident across the portfolio, where only 9 out of 148 projects with gender targeting addressed learning for boys.22

The evaluation found that equity-related issues other than gender are targeted to a lesser extent in World Bank projects. Fifty-one percent of projects target children in rural, remote, or nomadic areas, whereas 44 percent support children living in poverty (figure 3.6). Case studies indicated that, in most instances, rural poor people were defined with reference to geography rather than relative levels of income within relevant communities or schools. Furthermore, projects also address, to some extent, the educational needs of children with disabilities (39 percent); those facing ethnic, religious, caste, or linguistic disadvantages (33 percent); and those affected by conflict (16 percent) or who are out of school (15 percent), noting that it is not possible through analysis of PADs to identify the level of funding in support of these groups in projects or the extent to which support was marginal or integral. Box 3.3 provides contrasting examples of the attention to inclusion by the World Bank observed in two case studies.

Figure 3.6. World Bank Projects Targeting Equity-Related Issues

Source: Independent Evaluation Group portfolio analysis.

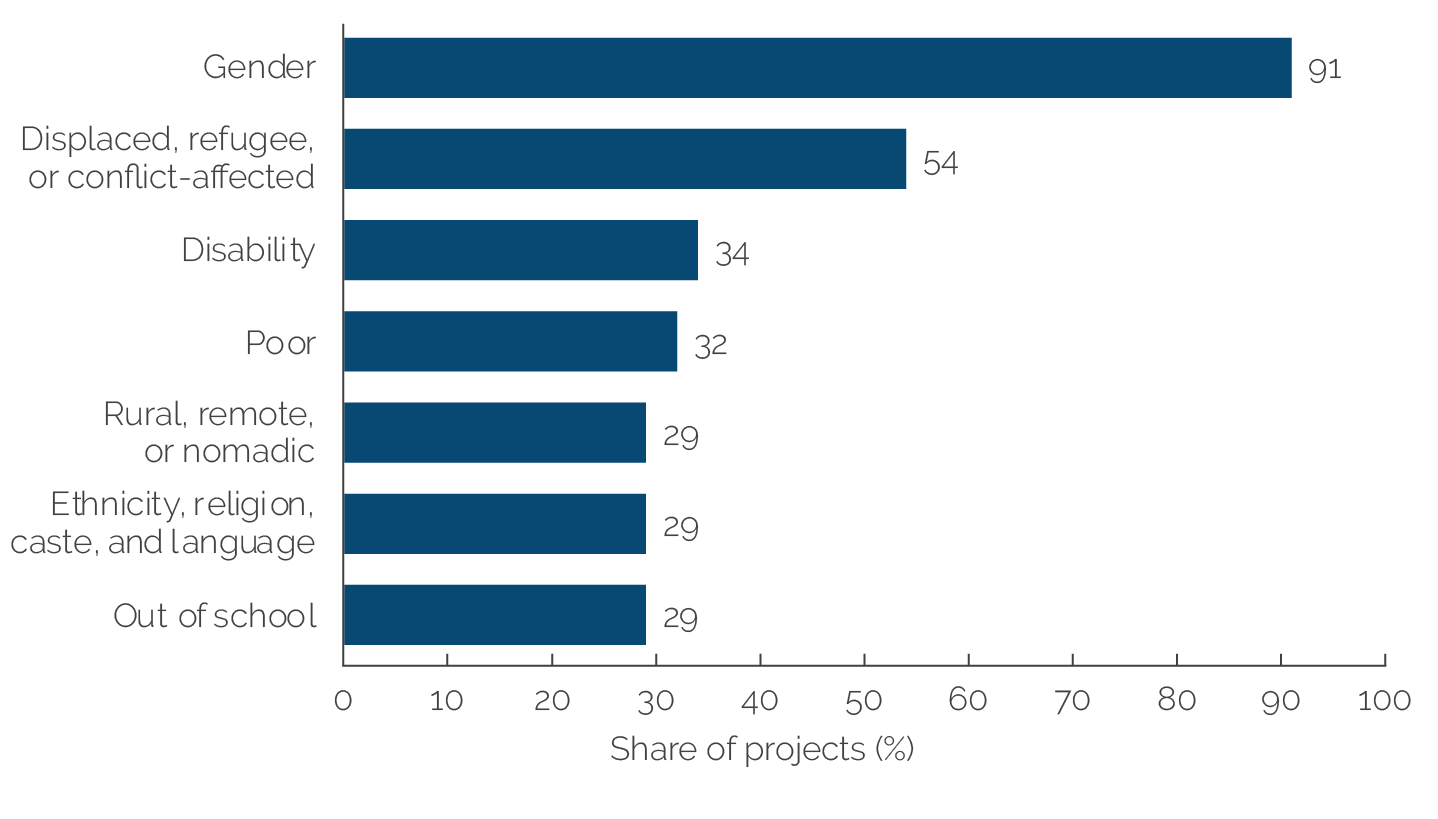

The evaluation identified progress in recognizing barriers and targeting activities among multiple groups but also found insufficient attention to measuring equity (beyond gender and girls)—an important downstream aspect of the evaluation framework and learning for all. World Bank projects produce limited equity-related disaggregated data (except for gender), which makes it difficult to assess the extent to which target groups have been reached or their needs addressed. The evaluation analyzed the results frameworks in project documents to find the extent to which the targeting of specific groups is reflected in the indicators. The findings show significant variation across target groups (figure 3.7). Projects addressing gender disparity have indicators with gender disaggregation in nearly all cases (91 percent). Fifty-four percent of projects focusing on conflict-affected children also include corresponding indicators to measure progress. However, for projects that include other groups, such as people with disabilities, rural residents, or out-of-school children, in their targeting, only about 30 percent have indicators that capture the progress of those target groups.

Box 3.3. Examples of World Bank Support for Inclusion in Pakistan and Sierra Leone

Pakistan: Girls’ education is the World Bank focus in Pakistan and is addressed both in lending and in advisory services and analytics. For example, Constraints to Girls’ Education (2020) focuses on barriers to girls’ education and assesses the potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on girls’ return to education. The Country Partnership Framework and project documents refer to displaced populations, and International Development Association support has been provided for refugees and host communities. The World Bank has also focused on inclusiveness in education related to disability through school infrastructure, teacher development related to disability in Punjab, and an Inclusive Education Policy Landscape Study.

Sierra Leone: The World Bank’s involvement in supporting the government’s Free Quality School Education initiative (launched in 2018) has taken a wide-angled approach to inclusion, with a focus on poor people and rural dwellers, but it has also focused on girls and, more recently, on people with disabilities. Certain issues, such as language of instruction, have not yet been addressed, although the World Bank is considering how it can engage in what is regarded as a politically complex issue. The World Bank also championed the National Policy on Radical Inclusion in Schools, which enables and supports pregnant girls to return to school after COVID-19, unlike the situation that pertained after the Ebola outbreak. The National Policy on Radical Inclusion in Schools also embraces children with disabilities. The Country Partnership Framework notes that social safety net programs are to include disability in targeting criteria to reduce social exclusion and refers to “soft conditions” that will be used to signal to parents the importance of enrolling students on time and keeping them in school. Under the Free Education Project, the World Bank identified inadequate support to children with disabilities and barriers to their inclusion in and benefit from education. The project will address relevant issues by increasing access and improving the learning environment based on a disability analysis undertaken during project preparation.

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Figure 3.7. Projects Targeting Specific Groups with Indicators on the Target Group

Source: Independent Evaluation Group portfolio analysis.

Operations in 6 out of 10 case countries included some level of support for children with disabilities, including a requirement for universal design in school-related infrastructure development supported by the World Bank, provision of scholarships for children with disabilities, provision of learning materials, and teacher training (box 3.4). In some cases, the World Bank supported production of enhanced data in children with disabilities. In Kenya, the World Bank supported studies of cost-effective models for the expansion and delivery of primary education to disadvantaged groups, including children with disabilities, and all infrastructure development under World Bank projects was required to be disability friendly. In Sierra Leone, the GPE supported the Revitalizing Education Development in Sierra Leone project (2014), which supported the development of an inclusive education policy. Project preparation for the Free Education Project (2020) included a disability analysis to inform how the project would support a regular monitoring system of student attendance and learning outcomes among children with disabilities and promote universal design as part of the national school construction strategy.

Box 3.4. Examples of World Bank Support for Children with Disabilities in Four Case Countries

Ethiopia: Pilot activities provided braille books and supported grants to help raise awareness of disability issues. The World Bank also financed setting up about 800 resource centers, each of which supported a cluster of schools, and technical assistance to support a special needs education strategy.

Nepal: The World Bank supported grants to integrated schools for resource classes for children with disabilities. COVID-19 additional financing covered several activities to support inclusion, such as disability-inclusive content, use of sign interpretation on televised content, and targeting of students with disabilities as a key group under a back-to-school sensitization campaign.

Tajikistan: Four percent of the budget for the Global Partnership for Education project (2013) was allocated to inclusive education of children with disabilities. That budget was used to promote campaigns of inclusive education and socialization of children from boarding schools and to provide personnel to support children with disabilities and their teachers. It was also used for school upgrades (pathways, accessible latrines, and ramps), although the case study interviews suggested that maintenance of the improvements had been neglected.

Viet Nam: The Quality Improvement of Primary Education for Deaf Children Project is the only World Bank–supported basic education project in Viet Nam that addresses issues related to children with disabilities.

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

As part of the World Bank’s corporate commitment to inclusive development for disability, all education operations aim to be inclusive of disability by 2025. To meet the criteria for a disability tag, a project must include stakeholder engagement during preparation, inclusive design features or one activity to benefit learners with disabilities, and one disability inclusion–related indicator or indicator disaggregated by persons with disabilities. IEG’s review of tagging for citizen engagement and gender identified tension between meeting corporate targets and ensuring the quality of engagement (World Bank 2018a). In both cases, IEG cautioned that a corporate commitment to increase tagging in 100 percent of projects, without adequate design, implementation, and monitoring support, could inadvertently generate a “check-the-box” attitude, to the detriment of quality (World Bank 2018a). Applying IEG’s finding to the disability tag highlights a need to support TTLs with disability expertise so that the World Bank’s support and dialogue integrates disability into clients’ planning and implementation of education systems, consistent with leading education systems.

Language of instruction was found to affect learning outcomes in 9 out of 10 case study countries, and the World Bank provided some level of support in 7 out of 9 cases without addressing underlying barriers, such as teaching quality and broader capacity issues. The literature,23 including the recent literacy policy package of the World Bank, recognizes a potential barrier to learning in the choice of language used in instruction (Chong Soh, Del Carpio, and Wang 2022; UNESCO 2022), particularly for children from ethnic minority and refugee communities. In the case studies, financial support was used to produce instructional materials and textbooks in additional languages, as in Tajikistan with the GPE grant, in Nepal with the development of textbooks in more than 20 languages for first through eighth grades, and in Kenya with the International Development Association grant from the Window for Host Communities and Refugees. In Viet Nam, ethnic minority children receive additional support from local language assistants (who are bilingual) in schools. Viet Nam has also piloted incorporation of bilingual instruction for children at the primary level (and preschools) with the support of Save the Children and a prior action in a development policy operation supporting policy change. Case studies identified teachers’ knowledge as the predominant implementation barrier. For example, the Ethiopia Education Sector Strategy sets the ambitious goal of every learner becoming multilingual—fluent in their first language, the official language, and English. Although instruction in primary grades is conducted in the native language, teachers are also expected to provide instruction in English because it becomes the medium of instruction in secondary schools, despite limited teaching capacity in English, as noted by local researchers.24 The joint GPE–World Bank report for Tajikistan highlights the negative effect of this lack of capacity on learning—having a teacher who was a native Uzbek speaker was associated with a decrease of about seven words per minute in the school-level oral reading fluency score for students in grades 2 and 4 (World Bank 2019d). Viet Nam has also recognized the need for further changes in preservice and in-service training in relation to the ethnic minority language of instruction.

Improving Teaching and Instruction

As recognized in World Bank analysis and operational support, the lack of an adequate number of well-qualified teachers in basic education is linked to a broad range of factors, such as funding, recruitment, monitoring, and motivation.25 Case studies highlighted challenges in certain countries (among them Chad, Ethiopia, Kenya, and Sierra Leone) in recruiting and retaining teachers in rural, remote, or conflict-affected areas. Recruitment of teachers was directly addressed in World Bank projects in Brazil, Chad (regularizing the recruitment of inadequately qualified community teachers), Nepal, and Pakistan (recruitment of more women teachers). Retention was addressed in certain World Bank projects through the provision of support for incentives, such as allowances and accommodation, to try to persuade teachers to move to and stay in certain, usually rural, locations. However, a lesson drawn from completion reports is the lack of sustainability once incentives conclude. In countries with growing demographics, the challenge of ensuring quality teaching and education will increase, given the need for qualified teachers, particularly in Africa (box 3.5; Bashir et al. 2018).26

The World Bank’s primary response to the challenges associated with quality teaching is the provision of support for on-the-job training. In-service training can be an important input in basic education systems, particularly where a cadre of well-qualified teachers exists and where the training is designed to complement and build on existing knowledge, expertise, and competence. Literature highlights the importance of professional development when teachers are given follow-up support to be able to practice and use the knowledge and skills that result in changes to the learning experience of students (Evans and Popova 2016). Follow-up support as a single activity to complement the training was found in 40 operations, whereas support through a continuous mechanism offering regular supervision or mentoring was identified in 70 out of 188 operations with on-the-job training. This is a design improvement from what IEG identified (World Bank 2019c); however, few of these operations assess or monitor the fidelity of follow-up support (38 out of 110), as is the case with the Enhancing Teacher Effectiveness in Bihar project in India, which uses school-based assessments to judge the quality of teaching and learning through classroom observation and lesson planning. When effective training is delivered, it can improve student test scores (McEwan 2015), particularly for girls (Aslam et al. 2016).

The World Bank’s measurement of changes in teaching because of training supported by its operations is limited. A review of key and intermediate performance indicators across operations containing teacher training identified output measurements related to the number of teachers trained or the number of teachers trained in particular types of pedagogy (such as psychosocial, reading, mathematics, and gender-sensitive) or the inclusion of particular content in training modules (such as gender-sensitive behavior and climate awareness training). Twenty-two operations (out of 188 with on-the-job training) systematically tracked the impact of training on teachers’ practices; participation in training was monitored in the remaining operations. The assessment and evaluation of training is particularly needed because IEG found few operations with the combination of effective characteristics to realistically deliver enhanced learning outcomes (World Bank 2019c). Thus, the World Bank is missing a critical feedback loop to learn from operations and ensure that training is in fact improving the capabilities of the stock of teachers and resulting in better learning outcomes.

The World Bank has placed a relatively limited emphasis on preservice training or career framework development compared with in-service training provision. Preservice training is cited as a planned activity or subcomponent in 91 (39 percent) of all basic education projects approved during FY12–22, whereas on-the-job training is a planned activity in 80 percent of projects. The evaluation confirmed the finding of IEG’s Selected Drivers of Education Quality: Pre- and In-Service Teacher Training that support for in-service training represented a partial response to the much deeper challenge and that the World Bank rarely engaged with the more fundamental and more difficult development challenge associated with the comprehensive strengthening of preservice training institutions (World Bank 2019c). The majority (60 percent) of the 91 projects that cite preservice training are in the Africa Region, where the learning crisis is most acute and where teaching standards are most challenged. When asked about the lack of attention to preservice training, World Bank staff recognized the gap and suggested that the lack of engagement might be associated with the scale and cost of the challenge or the fact that teacher training institutions may be highly political. In many client countries, including the case countries, there is a shortage of qualified teachers, and a sizable proportion of qualified teachers have low levels of education and skill, making it unlikely that preservice institutes can produce quality teachers with the required level of skills. This suggests a need for the World Bank to also address the flow of teachers who enter the system with minimum requirements.27

Box 3.5. Case Study Countries Facing Large Challenges from Population Growth

The analysis of demographic trends in the Independent Evaluation Group’s 10 case study countries using actual (2000–21) and projected (2022–40) population data of 5- to 14-year-olds from the United Nations population data portal shows significant population growth in countries such as Ethiopia and Pakistan and population decline in countries such as Nepal and Viet Nam. Chad is in its own category; its overall projected population growth rate is over 3 percent—the eighth fastest growth rate in the world (the top 20 are in Africa). In raw terms, its population of 5- to 14-year-olds will grow from 2.5 million to 7.5 million in 2000–40. A second set of countries, including Ethiopia, Iraq, Kenya, Pakistan, Sierra Leone, and Tajikistan, will also experience growth. In this group, Ethiopia, Iraq, and Sierra Leone stand out, with about 200 percent growth in this period (2000–40). Kenya, Pakistan, and Tajikistan are at a lower positive rate, with populations that will increase by 50–75 percent. Interviewees strongly emphasized the scale of the challenge associated with this growth, even without factoring in climate change impacts, fragility, and vulnerability.

Source: Independent Evaluation Group analysis of data from the United Nations population data portal.

Support for Measurement of Learning

During FY12–22, the World Bank has developed a large volume of GPG and capacity-building programs financed by trust funds to support learning measurement.28 Among those programs was an effort to improve client assessment capacity using the READ trust fund in eight countries. In more recent efforts, with READ 2 and the Learning Assessment Platform, the focus has shifted to measuring foundational learning in eight countries (Armenia, Cambodia, India, the Kyrgyz Republic, Mongolia, Nepal, Tajikistan, and Viet Nam), which received support to build capacity in learning assessment, data analysis, and use of data in decision-making. READ 2 also measured indicators of client capacity. Box 3.6 describes the use of structured pedagogical approaches in case studies, which are evidence-based interventions to improve foundational learning.

Box 3.6. What Are Structured Pedagogical Approaches?

A recent review by the United Nations Children’s Fund defines structured pedagogy as “a systemic change in educational content and methods, delivered through comprehensive, coordinated [programs] that focus on teaching and learning, with the objective of changing classroom practices to ensure that every child learns” (Chakera, Haffner, and Harrop 2020, 5).

The Global Education Evidence Advisory Panel (which is co-hosted by the UK Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office; the United Nations Children’s Fund Office of Research–Innocenti; the United States Agency for International Development; and the World Bank) rated structured pedagogy as a “good buy” in its comprehensive review of cost-effective interventions in education. The review cites the potential for “step-by-step” lesson guides that are part of a “multifaceted instructional program” to help improve teaching, especially in contexts where teachers have low levels of capacity.

These approaches were used in 5 out of 10 cases, with planned use in another case as part of an upcoming project. Some followed a specific pedagogical approach, such as Teaching at the Right Level, whereas others were customized to the context, including student and teacher materials, teaching training, and follow-up support.

Some partners were supportive of increasing the use of structured pedagogical approaches by the World Bank to improve foundational learning. There are gains from baseline; however, children, after participating in some of the programs, can remain below the internationally recognized minimum basic levels of literacy.

The evidence also highlights the need to ensure that structured pedagogical programs are fully supported and aligned in the education system and context because successful programs incorporated materials that were tailored to their specific context, including delivery in the children’s native language instead of the national language. Less successful structured pedagogy programs may also have been unable to overcome substantial teacher capacity limitations and a lack of resources and other implementation weaknesses (He, Linden, and MacLeod 2007; Kerwin and Thornton 2016; Lucas et al. 2014). Thus, planning for the use of structured pedagogical programs requires understanding of the weaknesses of the system and the reasons they exist in that context.

Sources: Independent Evaluation Group case studies and interviews; Chakera, Haffner, and Harrop 2020; Crouch 2020; He, Linden, and MacLeod 2007; Kerwin and Thornton 2016; Lucas et al. 2014; Piper and Dubeck 2021.

Nearly two-thirds of portfolio operations supported learning assessment activities. All leading education systems routinely measure learning because it is not possible to know that improvement is occurring without regular monitoring of student learning data from a national sample across various grade levels. Projects containing learning assessment activities predominantly supported assessment capacity building (80 percent of operations), assessments of various types (75 percent), and dissemination and use of learning data (50 percent). Thirteen percent of these operations used learning surveys, which measure learning during the operation but do not constitute a regular system of learning assessment. Nearly all projects in the Middle East and North Africa since 2017 have included assessments, making it the Region with the most assessment-related activities.

World Bank financing predominantly supported countries’ own national assessments (in 44 countries) and subnational assessments (in 6 countries). Other types of assessment, such as early-grade reading or mathematics assessments (in 19 countries), international or regional assessments (in 16 countries), or classroom assessments (in 15 countries), were less frequently supported. Assessments predominantly covered grades 6 and lower (92 percent of operations supporting assessments) and assessed reading (98 percent) and mathematics (84 percent). More countries financed national assessments and international or regional assessments during the second half of the evaluation period, but the use of early-grade reading or mathematics assessments decreased during the second half of the period. Nearly half of these operations have a regular frequency of administration of the assessment, such as every two or three years (47 percent); the remainder are administered twice during the operation (35 percent) or once during the project (23 percent). A national sample is used when national assessments are supported because it is important to know what children across the country have learned. The countries with repeated assessment support continue to support national assessment and have also included plans for participation in international or regional assessment (Angola, the Dominican Republic, Ethiopia, India, Kosovo, Nicaragua, Pakistan, Peru, Rwanda, Moldova, São Tomé and Príncipe, and Sri Lanka), showing government commitment to measure learning with accessible and comparable cross-national data. Learning outcome data remain scarce in low- and middle-income countries, making it possible to partially assess minimum proficiency levels in 4 out of 10 case countries only (table 3.3). Out of 91 portfolio countries, 47 reported data on the proportion of students at the end of primary education achieving at least a minimum proficiency level in reading, whereas only 27 countries have such data in reading for lower secondary. All the case study countries have some kind of national assessment data, but the extent to which they have a systematic learning assessment function in place varies. In Ethiopia and Kenya, data are dated or not accessible to the public. At one extreme of the assessment function, in Sierra Leone, examinations have been used to determine progression from one level of education to another, but there are limited mechanisms to assess learning as a stepping stone toward identifying areas for curricular modification, teacher training, or overall system improvement. Brazil stands at the other extreme with a highly evolved national monitoring system augmented with individual state (and even municipality) data based on large-sample assessment. Only 3 of the 10 case countries have data from large-scale international assessments—Brazil (Program for International Student Assessment and the Progress in International Reading Literacy Study), Pakistan (Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study), and Viet Nam (Program for International Student Assessment). Some case study countries also participated in regional assessments, including Laboratorio Latinoamericano de Evaluación de la Calidad de la Educación (Latin America, only Brazil); the Southern and Eastern Africa Consortium for Monitoring Educational Quality (Africa, only Kenya); the Programme for the Analysis of Education Systems (French-speaking Africa, only Chad); and the Southeast Asia Primary Learning Metrics (Southeast Asia, Viet Nam). The World Bank is supporting Iraq, Kenya, and Tajikistan with participation in international assessments in 2023. The Early Grade Reading Assessment, supported by the United States Agency for International Development, and the GPE have provided early reading data in nearly all case study countries. The limited progress over the decade in establishing learning outcome measures is illustrated in table 3.3, including the need to improve learning.

Table 3.3. Minimum Learning Proficiency in Reading and Mathematics at the End of Primary and Lower Secondary Education in Case Study Countries (percent)

|

Country |

Reading at the End of Primary Education |

Mathematics at the End of Primary Education |

Reading at the End of Lower Secondary Education |

Mathematics at the End of Lower Secondary Education |

|

Brazil |

44 |

29 |

50 |

32 |

|

Chad |

8 |

2 |

— |

— |

|

Ethiopia |

— |

— |

— |

— |

|

Iraq |

— |

— |

— |

— |

|

Kenya |

47 |

74 |

— |

— |

|

Nepal |

— |

— |

— |

— |

|

Pakistan |

— |

8 |

— |

— |

|

Sierra Leone |

— |

— |

— |

— |

|

Tajikistan |

— |

— |

— |

— |

|

Viet Nam |

82 |

91 |

90 |

84 |

Source: Independent Evaluation Group calculation of United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization Institute for Statistics data from September 2023.

Note: Large-scale international assessment programs postponed administration and reporting of assessments for the years 2020–2022, which has affected coverage. — = not available.

Monitoring and Evaluation

Monitoring and evaluation of improved learning outcomes is specified in 33 percent (n = 77) of project development objectives (PDOs) in the basic education portfolio. The focus on improved learning outcomes in PDOs is higher in Africa (43 percent of projects). Improving the quality of education is an objective in 62 percent of operations that typically focus on improvements to the learning environment (such as enhanced infrastructure, textbooks, or teachers trained)—often prerequisite conditions to improve learning. Out of the 77 projects with PDOs that address improving learning outcomes, 48 have outcome indicators measuring learning outcomes. Among the 48 projects, 81 percent focus on primary grades, measured predominantly in reading (83 percent) compared with mathematics (58 percent). These indicators are drawn from national (31 percent), subnational (25 percent), and other assessments (such as early-grade reading or mathematics assessments). The Middle East and North Africa is the only Region where all projects have contained indicators on learning outcomes at the output or outcome levels since 2017. Analysis of IEG ratings shows that operations with learning indicators receive lower ratings than operations with less ambitious objectives, which is significant only at the 0.1 level.

Indicators designed to capture learning outcomes are not typically included in CPFs. For example, indicators related to basic education were included in CPFs for 7 out of 10 case countries. However, as set out in table 3.4, these indicators tend to be general and rarely related to learning outcomes; indicators are provided to capture learning outcomes in 2 out of 10 case countries, Ethiopia and Iraq. As with the measurement of project effectiveness and success, the measurement of enhanced learning outcomes at country program level is limited.

The implementation of World Bank EMIS interventions is challenged by inefficiencies in country systems. The World Bank has provided combinations of support that include interventions to promote the development of an EMIS, tablet-based data collection that feeds into annual censuses, technical assistance to support capacity development, and others. However, the efficacy of any input is contingent on many facets of the system being equally developed in parallel. Significant gaps continue to exist in that regard. For example, most country cases found an absence of a culture that supports monitoring and evaluation and found gaps in the human resource capacity required at all levels of the system—from central to local—to ensure an effective data management system. The evaluation also identified the need for “joined-up” data management across the system (despite investment in EMIS), the need for greater and more consistent disaggregation of data for marginalized groups, and quantification of learning losses associated with the COVID-19 pandemic.

Table 3.4. Basic Education Quality–Related Indicators in Latest Country Partnership Frameworks in Case Study Countries

|

Country |

Latest CPF |

Indicator(s) |

|

Brazil |

FY18–23 |

Objective 1.3—increased effectiveness of service delivery in education—has the following quality-related indicator: reduction of dropout rate in the first year of public secondary schools (baseline [2016]: 9.8%; target [2022]: 7.0%). |

|

Chad |

FY16–20 |

Objective 3.2—improved access to and quality of education—has the following quality-related indicators, all of which have baseline and target values. Indicator 3.2.2: Additional classrooms built or rehabilitated at the primary level (number). Indicator 3.2.3: Document resource centers created and equipped (number). Indicator 3.2.4: Additional qualified community teachers (number). |

|

Ethiopia |

FY18–22 |

Objective 2.4—improved basic education learning outcomes—has the following learning outcome indicator (with baseline and target values defined): students scoring at “below basic proficiency” in English and mathematics (NLA subject scores; percentage). |

|

Iraq |

FY22–26 |

Objective 2.2—improved education quality, better skills, and economic opportunities for youth and women—has the following quality learning outcome indicators (with baseline and target values defined). Indicator 2.2.1: Percentage of early-grade students who can read with comprehension (by gender). Indicator 2.2.2: Percentage of students completing primary education; percentage of students completing secondary education (by gender and quintile). |

|

Kenya |

Focus on youth skills development. |

|

|

Nepal |

FY19–23 |

Objective 3.1—improved equity in access to quality education—has the following quality-related indicator with baseline and target values provided: retention rate of poor students to grade 12 in community schools in selected districts. |

|

Pakistan |

FY15–20 |