Confronting the Learning Crisis

Chapter 1 | Background

Highlights

The COVID-19 pandemic resulted in severe learning losses and underscored the crucial role of basic education for children and families beyond learning, such as socialization, nutrition, and social-emotional well-being. Those losses also highlighted longer-term global learning deficits.

The roots of the learning crisis lie in a historical focus on basic schooling access without commensurate investment in quality and in approaches to quality improvements that focus on inputs and outputs—books, curriculums, teachers, management capacity—applied to complex systems subject to social, political, cultural, structural, logistical, and institutional crosscurrents that require thorough analysis and a sophisticated, strategic systems approach.

The children most often failed by their education systems are those already disadvantaged by poverty, location, ethnicity, gender, or disability.

Improved learning outcomes for all are more difficult to motivate and more costly to achieve than improvements in access.

A recent World Bank study reports that governments in low- and middle-income countries closed schools during the COVID-19 pandemic for an average of 37 weeks—the equivalent of one year of schooling (Schady et al. 2023). The study calculates that “1.3 billion children…missed at least half a year of school, 960 million missed at least a full year, and 711 million missed a year and a half or more” (Schady et al. 2023, 62). Every month of school closure represented more than a month of learning loss. The time students spent studying also fell, even where remote learning was available: “In Ghana, Liberia, and Sierra Leone, the time spent learning per day declined by 71 percent, or six hours per day, compared with time spent when schools were open. In Kenya, the decrease was 61 percent, and the average student spent only two and a half to three hours per day on learning-related activities” (Schady et al. 2023, 64). Moreover, access to remote technology was not uniform within countries, leaving those most at risk even more vulnerable to learning loss. These severe learning losses, if not addressed, will have consequences for the long-term economic prospects of the children affected and for their countries (Rodriguez et al. 2020).

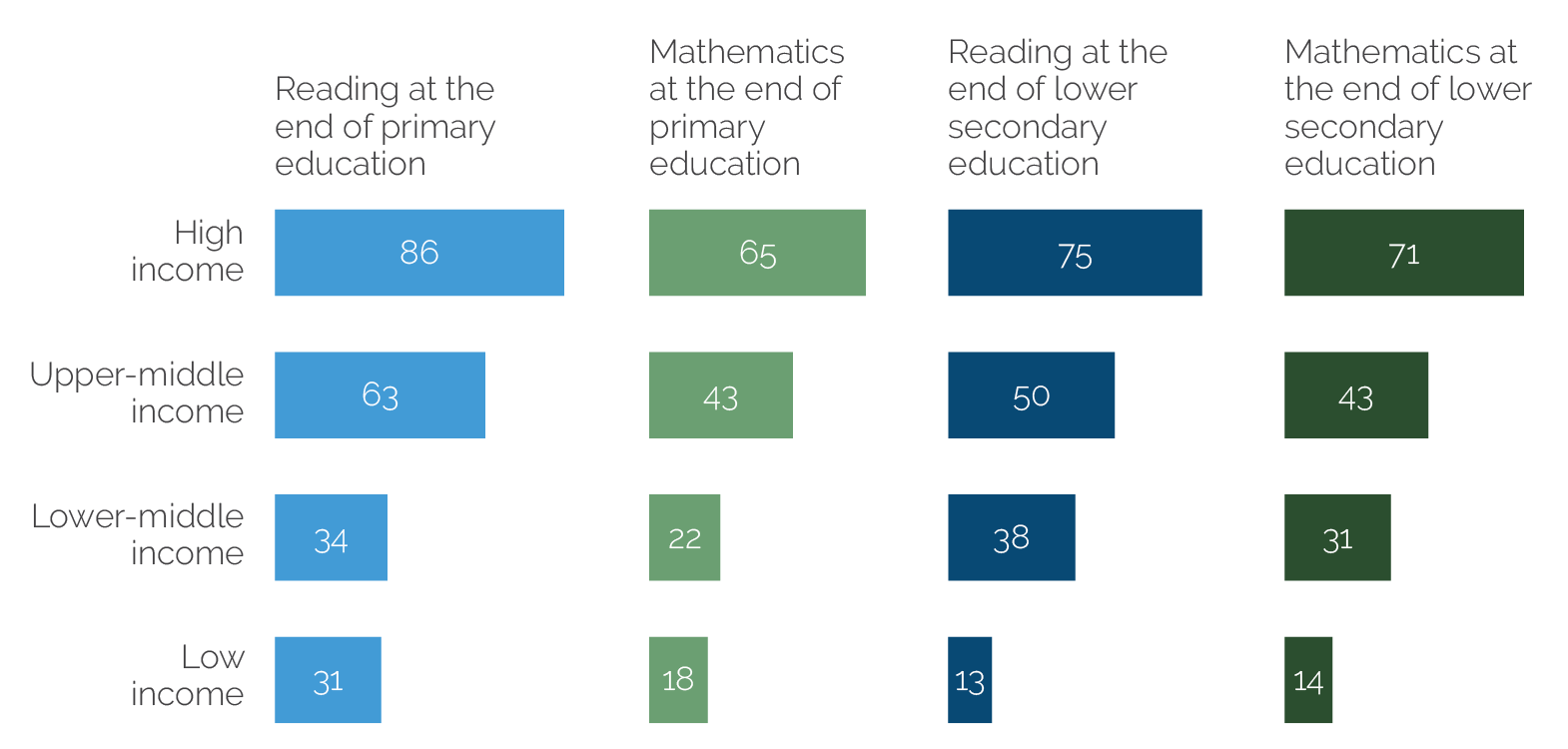

The learning losses because of COVID-19 school shutdowns only extended and deepened a long-standing challenge—low learning outcomes and persistent learning poverty are common in the basic education systems of low- and middle-income countries. The World Development Report (WDR) 2018 found that students were losing an average of one to six years of schooling as a result of low educational quality (World Bank 2018b). The result is that 53 percent of all 10-year-old children in low- and middle-income countries experienced learning poverty. Furthermore, learning poverty increased to 57 percent by 2019. In low-income countries, learning poverty was 91 percent by 2019, compared with 9 percent in high-income countries (World Bank, UNESCO, et al. 2022). That was the situation even before the learning losses arising from the school shutdowns during the COVID-19 pandemic. (See box 1.1 for definitions of learning poverty, reading proficiency, and learning loss.) Figure 1.1 highlights the divide between high-income and low-income countries in achieving minimum proficiency levels, which will be used to measure progress toward Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) indicator 4.1.1 in reading and mathematics with the most recent United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) Institute for Statistics data.

Figure 1.1. Share of Students Achieving at Least Minimum Proficiency Levels in Reading and Mathematics by Country Income Level

Source: United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization Institute for Statistics, September 2023.

Learning is important both for individual well-being and for economic development. Filmer et al. (2018) note that studies of learning and skills among adults have found learning effects on individual earnings, health, financial behavior, social mobility, and economic growth. Hanushek’s research confirms that the growth of countries and growth rates of nations are closely linked to the skills of their population. The implication of the research is the importance of raising basic skill levels in countries (particularly those farthest behind in skills) to enable their participation in a modern productive economy (Hanushek 2022; Hanushek and Woessmann 2008).

The roots of low learning quality in basic education (primary through lower secondary school) lie in part in approaches from international development organizations that focus on inputs and outputs rather than outcomes.1 For example, the Asian Development Bank report on lessons learned from its work in the education sector indicates that policy reforms that are lacking attention to political realities and understanding of country contexts are bound to fail (ADB 2013). A report on bilateral support to primary education by the UK Department for International Development (replaced by the Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office) states that the emphasis on enrollments “in part reflects how governments and donors collectively have interpreted Millennium Development Goals for Education” (Comptroller and Auditor General 2010, 7). The report also specifies that the Department for International Development’s approach was evolving toward a focus on education quality. The Aga Khan Foundation notes that, in consequence of the focus on enrollments, “the very gains in school access have exacerbated the quality issue” (Aga Khan Foundation 2010, 4). More recently, documents from the US government and the UK Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office, among others, acknowledge a narrow focus on increasing enrollments in pursuing the education targets for the Millennium Development Goals, which came at the cost of attention to education quality.

Box 1.1. Key Concepts in Learning Measurement

International metrics for education have evolved over the past 25 years. With the Millennium Development Goals, attention was focused on measuring education access. Learning outcomes, which are more challenging to measure, were less common and less developed. In 2012, the Learning Metrics Task Force, convened by the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization Institute for Statistics and the Center for Universal Education at the Brookings Institution, issued six recommendations to improve learning measurement, supporting efforts to shift global focus and investment from universal access to universal access plus learning.

The adoption of the Sustainable Development Goals in September 2015 committed countries and their development partners to improving learning outcomes for all and posed challenges for the measurement and tracking of learning. Sustainable Development Goal target 4.1 aimed to ensure that by 2030, all girls and boys would complete free, equitable, and quality primary and secondary education, leading to effective learning outcomes. Linked to target 4.1, Sustainable Development Goal indicator 4.1.1 focused on the proportion of children and young people (in the second and third grades, at the end of primary education, and at the end of lower secondary education) achieving at least a minimum proficiency level in reading and mathematics, with information disaggregated by gender.

The development of the learning poverty indicator by the World Bank and the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization joined school deprivation with learning deprivation in a single measure. Learning deprivation in this indicator is based on reading proficiency, which is expected to be accomplished by the end of primary education and is a proxy for other foundational learning. Hence, children unable to read and understand a simple text by age 10 years are described as “learning poor.” Conceptually, “learning poverty” begins with the share of children who have not achieved minimum reading proficiency (as measured in schools) and is adjusted by the proportion of children who are out of school.

Reading proficiency is measured by the ability to read at grade level. By age 10 years, or by the end of primary education at the latest, a child should be able to read a simple text, fluently, in their own language. In rural India in 2016, only half of fifth-grade students could fluently read text at the level of the second-grade curriculum, which included sentences (in the local language) such as “It was the month of rains” and “There were black clouds in the sky.”

Learning loss—the loss of knowledge and skills or the reversal of academic progress—can occur with any extended break or disruption in schooling, including seasonal breaks, frequent changes in school, dislocation as a result of social strife, and school closures. Learning loss can affect literacy, numeracy, and social and emotional development and can increase learning poverty by increasing either or both learning deprivation and schooling deprivation. Hence, “during the COVID-19 pandemic, after lengthy school closures and remote instruction that was less efficient than learning in schools and was provided with unequal access, the learning poverty rate could reach as high as 70 [percent; from a base of 57 percent]” (World Bank, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, et al. 2022, 4). The largest losses were in Africa, where second-grade students in South Africa suffered up to 70 percent learning loss and fourth-grade students in Malawi lost two years of learning.

Sources: Azevedo et al. 2021; World Bank 2018b, 2021d; World Bank, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, et al. 2022.

Who Is Affected?

The children most often failed by their education systems are those already disadvantaged by poverty, location, ethnicity, gender, or disability. Understanding the barriers to learning and discrimination has become increasingly sophisticated in the literature on education strategy and policy. Analysis has moved beyond metrics of economic status (with gender disaggregation) to include social identity and a broader equality agenda, while also noting how discriminatory barriers overlap and compound, such as the multiple barriers faced by a girl from a poor family living in a rural area who is a member of an ethnic minority. Yet poverty is at the root of most exclusion from school and from learning (UNICEF 2020). As many as 44 percent of girls and 34 percent of boys from the poorest quintile never attend any school or drop out before completing primary education. There is a serious equity problem in the distribution of public financing, such that the poorest children—who face compounding barriers including location, disability, or ethnic origin—are failed further (UNICEF 2020).

Children in crisis situations are often failed by their education systems. Novelli et al. (2014) found that recognition of the importance of education is less pronounced in the agenda-setting process in fragile contexts and elsewhere compared with both the humanitarian aid and security sectors. UNESCO and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) highlight the situation of children in conflict-affected countries, who account for just 20 percent of the world’s children of primary school age but for 50 percent of those who are out of school, and note that entrenched gender roles often determine whether a child enrolls and stays in school (UNESCO UIS 2015). The report emphasizes that education is often delivered in a language that children neither speak nor understand, which is a barrier to learning for many. UNICEF (2020) indicates the importance of focusing education funding on children during and after emergencies—at present, only 2.6 percent of humanitarian funds go to education. Only half of refugee children go to primary school, and less than a quarter are in secondary school. Children in conflict-affected countries are 30 percent less likely to complete primary school and 50 percent less likely to complete lower secondary education.

A Complex Problem

The issues involved in improving the quality of basic education are multilayered, including social, structural, logistical, and institutional matters that require a sophisticated analysis, understanding, and approach. Clearing the obstacles to orienting and aligning basic education toward learning requires ensuring that (i) children are prepared to learn, (ii) teachers are well trained and motivated, (iii) learning inputs are available and culturally and grade-level appropriate, and (iv) management and governance of the system have the capacity and authority to coherently integrate the various factors (World Bank 2018b). To address this level of intertwined complexity, the literature (UNICEF 2023; USAID 2022; World Bank 2018b) maintains that development organizations need a deep understanding of context when supporting education reform and that this can be supported by a greater emphasis on systems-based approaches to education.

Improved learning outcomes are more difficult to generate and are more costly and complex to achieve than improvements in access. Improving learning for all involves, for example, enhanced teacher quality; alignment of curriculum and textbooks with local contexts reflecting local language and culture; investment in education equity to ensure equality of opportunity (rather than, simply, access) for diverse students with reference to socioeconomic status, gender, disability, and geographic location; and effective assessment systems to allow for the monitoring of progress. Grindle (2004) concludes that “from a political perspective,” access reforms are easier than quality reforms. This is because the latter can result in lost jobs and diminished control over decision-making or resources, such as budgets and people, and can introduce new pressures and expectations for students, teachers, management, and oversight (Kingdon et al. 2014). Clientelism, patronage, and corruption are the most intense political forces pushing states to expand education access by building more schools or hiring more teachers without an equal emphasis on improving education quality. The literature suggests that this is why “most [country] education policies are to do with expanding access to education, and providing inputs to schools, which require expenditure” (Kingdon et al. 2014, 35).2

Negotiating both the general complexity of education reform and oppositional factors of the political economy may be better done using a systems-based approach. The WDR 2018 advocated addressing the political economy barriers at all levels of the system to improve learning outcomes. Magrath, Aslam, and Johnson (2019) posit that the change in focus from access (output) to learning (outcome) has shifted the emphasis away from individual interventions and programs to entire education systems. Faul and Savage (2023) state that a systems-thinking lens would emphasize the importance of locally led, nonstandardized, and context-responsive education to enable all children to learn (and to love learning). However, Faul and Savage (2023, 16) find that “systems thinking in international education remains contentious because it refuses to tout a single, one-size-fits-all solution; that can never be adequate to the complexity of the learning and equity crises that learners face.” Instead, it recognizes the complexity of education systems and encourages use of an approach focused on short dynamic feedback loops to understand elements and functions within the system (box 1.2).

Box 1.2. What Is Systems Thinking?

Broadly, systems thinking enables a more holistic consideration of the following:

- System elements—both material (teachers and schools) and intangible (beliefs and information)

- The relationships between those elements and subsystems

- The structuring of the system and subsystems within it

- The functions of the system—both formal (stated) and informal (in practice)

- The positive and negative feedback loops and influence pathways in the system

The World Development Report 2018 observed poor alignment of education systems with learning goals because of technical complexities, pursuit of conflicting goals, and limited policy implementation capacity in government agencies responsible for learning. System incoherence occurred across learning objectives and responsibilities, information metrics, finance, and incentives.

Sources: Faul and Savage 2023; World Bank 2018b.

World Bank Approach to Learning in Basic Education

For more than two decades, the pursuit of enhanced learning outcomes has featured in World Bank literature, especially since the publication of its 2011–20 strategy, Learning for All: Investing in People’s Knowledge and Skills to Promote Development—World Bank Group Education Strategy 2020 (World Bank 2011). Previous education sector strategies and documents have also emphasized the need to measure student learning and achievement as an input to helping country clients achieve educational outcomes (World Bank 1999, 2005). The 2011–20 strategy explicitly made learning a priority. Subsequently, the WDR 2018 marked an important shift in the World Bank approach to education and highlighted the learning crisis (World Bank 2018b). It emphasized the need for context-specific solutions, especially those developed by the country client. Countries need support, the WDR 2018 suggested, to correct poor service delivery and address system-level technical and political challenges that allow low-quality schooling to persist.

Following the themes of the WDR 2018, the World Bank described its most recent approach to the learning crisis in Ending Learning Poverty: What Will It Take? (World Bank 2019b). The report focused on the difficult challenge of eliminating learning poverty, noting the inadequacy of continuing with business as usual. Realizing the Future of Learning: From Learning Poverty to Learning for Everyone, Everywhere elaborated on the response, taking on the added challenges posed by the global pandemic (World Bank 2020a). In these formal statements of intent, the World Bank set out to strengthen its efforts to confront learning poverty and to influence the focus on learning poverty at the global level by setting an operational global learning target to cut the learning poverty rate by at least half before 2030 and by introducing three key pillars of work: (i) a literacy policy package, (ii) a refreshed approach to strengthen entire education systems, and (iii) an ambitious measurement and research agenda. These three pillars aim to support countries to improve the human capital outcomes of their people.

In Realizing Education’s Promise: A World Bank Retrospective, which looks back at the World Bank’s approach, the World Bank strategy is further refined to address five pillars (World Bank 2023c). The document articulates an approach to the education sector focused on policy actions that are needed to accelerate learning and that characterize the way many successful systems operate. The five pillars—learners, teachers, learning resources, schools, and system management—are fundamental to a well-functioning school system.3 Measurement of learning is central to the World Bank’s approach, as has been consistently emphasized by the Learning for All strategy and the WDR 2018 (World Bank 2011, 2018b), requiring support for national assessment capacity building to help countries develop reliable, timely statistics about student learning.

The Independent Evaluation Group (IEG) has contributed to learning by the World Bank through several evaluations relevant to basic education. From Schooling Access to Learning Outcomes: An Unfinished Agenda—An Evaluation of World Bank Support to Primary Education called for strengthening the capacity of countries to track learning outcomes, ensuring the disaggregation of learning data across different income and social groups (World Bank 2006). It also recommended working with development partners to reorient their emphasis on completion of primary education to focus on learning outcomes for all. This would require the establishment of learning achievement indicators, baselines, and targets (both intermediate and outcome targets) to support learning outcomes, and technical and financial support to countries to set up systems for conducting repeated learning assessments, comparable over time and capable of tracking outcomes separately for disadvantaged groups. The evaluation found sector management capacity a common weakness in primary education projects and suggested that better organizational capacity assessments at the outset and better capacity-building programs might have helped reduce the problem. The IEG portfolio review of education operations concluded that poor people may be the last to benefit from the World Bank’s investments, that stronger monitoring and evaluation was needed in government programs supported by the World Bank, and that the factors contributing to variation in results needed to be better understood (World Bank 2010).4 A 2019 IEG evaluation of preservice and in-service training interventions found that World Bank engagement in training teachers before entry into the profession (preservice training) has been limited and has prioritized coursework, with less emphasis on other drivers of quality, such as screening, practicum, and quality assurance (World Bank 2019c). Instead, the World Bank has relied heavily on continued training during employment (in-service training) to address shortcomings in preservice training through support to programs for both underqualified and qualified teachers.

Evaluation Objective and Scope

The evaluation assesses the extent to which the World Bank has supported efforts to improve learning outcomes in basic education over the past decade, fiscal year (FY)12–22. It pays particular attention to the extent to which the World Bank has adopted a systems approach to its support for basic education as advocated in Learning for All: Investing in People’s Knowledge and Skills to Promote Development—World Bank Group Education Strategy 2020 and as reinforced since the publication of the WDR 2018. The evaluation also responds to the increased urgency of the learning crisis, a priority for the Board of Executive Directors, which has been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Thus, the evaluation has a secondary focus on support provided to address critical challenges to education delivery and the exacerbation of learning loss associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. It offers lessons and recommendations to inform the next education sector strategy and the further development of the World Bank’s approach to this persistent development challenge.

The evaluation examines World Bank inputs, including financial support, knowledge, policy dialogue, and strategic partnerships. The evaluation covers all operations approved during FY12–22, as detailed in appendix A. For case studies, it also includes relevant projects supported by other Global Practices (GPs) directly supporting basic education, such as cash transfer projects under the Social Protection and Jobs GP or development policy operations from noneducation GPs that incentivize education policy reforms or actions. The evaluation considers inputs to global knowledge and initiatives, such as teachers or learning assessment, as well as regional and country-level knowledge (the latter via country cases), based on a sample of knowledge products published during the FY12–22 period. In addition, the evaluation examines policy dialogue and the extent to which the World Bank engages with clients on learning outcomes aiming to maximize positive change and strategically leverage its points of influence. Support for data measurement and its analysis can be critical in informing policy dialogue and in leveraging political and administrative support in favor of reform and may require interconnectedness across sectors.

Evaluation Approach and Methods

IEG developed a conceptual framework based on the literature reviewed, including the most recent World Bank education strategy documents, and on high-level interviews to guide this evaluation’s data collection and analysis. The framework sets out the characteristics of a basic education system that seeks to deliver quality education for all (figure 1.2). The findings presented in chapters 2 and 3 are linked to broad areas of the framework.

The framework recognizes the necessary contextual conditions to support learning for all. These conditions include contextual factors, such as political commitment to education for all, capacity within the system to deliver on that commitment, and the level of funding available to support basic education for all. More recently, the context shifted with the COVID-19 pandemic, intensifying the learning crisis.

The framework presents the process by which the World Bank can support basic education systems to achieve learning for all. The process begins with systems analysis to fully understand the context and to identify binding constraints and understand why systems fail to improve learning outcomes. It also requires engagement with the full range of stakeholders, beyond the views of ministry officials, to arrive at clarity of intent (that is, access or learning) and political commitment for learning for all. With that clarity, the World Bank can offer country responses that draw on tailored combinations of its global, regional, and country resources. Support is necessary to ensure sufficient ongoing financial support; basic education reform is a lengthy process and requires sustained government and social commitment. Policies suitable to realize the agreed vision and support for the development of implementation capacity and technical expertise and management are required, as are measurement and assessment that deliver feedback for the ongoing calibration of policy and practice subject to the country context and the positioning of the country in the process toward realizing learning for all.

Evaluation Methods

The evaluation used a mixture of methods with a multilevel design, including case-based analysis, portfolio analysis of lending and advisory services and analytics (ASA), and key informant interviews. These core methods were supported by literature reviews related to global knowledge, the political economy of education, development partner understanding of the learning crisis and their response to it, and the characteristics of high-performing education systems. The evaluation also undertook analysis of secondary data for case countries, which related to population growth and learning assessment via regional and global assessments.

The evaluation questions were applied to relevant evaluation components to answer the overarching evaluation question. Appendix A describes the evaluation methodology in more detail. IEG met with Education GP management and task team leaders (TTLs) to ensure that the evaluation methods were likely to produce learning and evidence useful to ongoing efforts to improve learning outcomes. IEG also shared findings with a group of TTLs to ensure balanced interpretation in analysis and reporting.

Evaluation Questions

To provide insights for a new education strategy, the evaluation questions and scope were designed through a consultative process with key Education GP staff and management. The overarching evaluation question is as follows:

How has World Bank support for basic education contributed to the achievement of enhanced learning outcomes since the Learning for All strategy, and what can be learned from those efforts to inform support to the learning recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic?

To respond to this question, the evaluation answers the following subquestions:

- How effective has World Bank support for basic education (FY12–22) been in addressing the binding constraints that hinder the achievement of enhanced learning outcomes in client countries?

- To what extent and how effectively has the World Bank:

- Collaborated with country and global partners to support education quality and enhanced learning outcomes?

- Used feedback from evidence and experience to inform its work to support improved education quality and learning outcomes for all?

- How well prepared is the World Bank to address additional challenges to education systems that have arisen because of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic?

Limitations

The evaluation team found low-quality data or limited availability of data in some countries (particularly in fragile and conflict-affected countries or those with low institutional capacity), which limited the specificity and precision of the analysis. Mitigation strategies included ensuring that data collection was context driven, collaborating with experienced local consultants to facilitate data collection, working closely with the Country Management Units and leveraging the support of the Education GP, engaging with as many relevant stakeholders as possible to ensure as broad a perspective as possible, and working with and analyzing existing (secondary) data sets to provide robust coverage of any quantitative data available.

Some structural evaluation choices have a bearing on the nature of this evaluation. First, IEG limited its field travel to reduce its carbon footprint. Evaluators interviewed stakeholders via videoconferencing, and they were paired with experienced local evaluators. The pair worked closely with the Education GP and Country Management Unit in each of the 10 countries selected to ensure interactions, albeit remotely, and produced the needed information. To the extent possible, the evaluation engaged with teachers through representative organizations, such as trade unions. The evaluation scope excludes early childhood development. The evaluation recognizes that the World Bank is engaged in a continuum of interrelated support at this critical stage of life; however, to focus the evaluation, the scope was limited to basic education and education systems to ensure robust findings.5

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: M&E = monitoring and evaluation; READ = Russia Education Aid for Development.

- This report uses the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization International Standard Classification of Education definition of basic education, which includes level 1 (primary education) and level 2 (lower secondary education). For more information, see UNESCO UIS (2012).

- Hickey, Hossain, and Jackman (2019) observed that in more competitive political contexts, such as Bangladesh and Ghana, there was evidence of the partisan allocation of jobs and other rents at different levels of the education system, whereas access to free education was considered important to maintaining the rural electoral base. In Uganda, the persistence of an officially “fee-free” policy reflected ruling party fears that introducing cost-sharing would undermine rural political support, even though cost-sharing was believed necessary to raise existing very low educational standards.

- The approach identifies specific elements required for each of the five pillars: For learners, these are quality childcare, nutrition, early stimulation, and early childhood education; For teachers, these are meritocratic profession, effective human resource function of the education ministry, and continuous school-based professional development; For learning resources, these are a simple, effective curriculum; books and supportive technology; coaching and structured pedagogy; and a policy action that all students are taught at the right level; For schools, these are elimination of all types of violence and discrimination in schools, access to and participation in learning for students with disabilities, and universal access in built and virtual environments; For system management, these are enhancement of implementation capacity from schools to central ministries, career track for school leaders, clear mandates and accountability, measured learning, and merit-based professional bureaucracy.

- Critically, the evaluation found that many country programs did not assess the strength of political forces acting both in support of and against the change agenda. Instead, program designers widely presumed that decisions would be based on rational planning and technical merits, although research has shown that officials lack appreciation for the scale of the learning problem. Risk assessments for the many projects reviewed rarely mentioned politically motivated threats to project implementation and success. Thus, no mitigation strategies were formulated.

- The World Bank has increased its lending to early childhood education. Although its efforts have focused on access (Bedasso and Sandefur 2024), international evidence suggests that interventions such as early stimulation services for at-risk children and support for their parents have reduced intergenerational poverty (Gertler et al. 2014; Schweinhart 2007; Walker et al. 2005, 2006, 2011). Longer-term results from 31 years after receiving the services highlight the importance of serving disadvantaged children (Walker et al. 2017).