Addressing Gender Inequalities in Countries Affected by Fragility, Conflict, and Violence

Chapter 4 | Factors Enabling and Constraining Transformational Change

Highlights

Addressing gender inequalities related to women’s and girls’ economic empowerment and gender-based violence is seldom a priority in projects or country strategies.

Key informants believe that the World Bank Group’s support to a country’s gender agenda would be more impactful if the institution used its multiple strengths for this purpose.

Financial resources can generate transformational change while insufficient budgets can jeopardize project efficacy. The evaluation noted several cases where the lack of financial resources left projects with unfulfilled supply or unmet demand for its services.

Adequate gender expertise at the country level can foster regular policy dialogues with the government on the gender agenda, local stakeholder collaboration, the regular presence of the Bank Group in national gender networks and platforms, and internal coordination among Global Practice teams.

The Bank Group’s coordination and collaboration are strong with implementing partners on specific projects but weak with women’s rights organizations, donors, and international nongovernmental organizations on the broader gender agenda. The Bank Group’s engagement with opinion leaders and with men and boys is still limited but increasingly pursued.

Contextual factors can make it difficult for the Bank Group to achieve transformational change on gender-based violence and women’s and girls’ economic empowerment in countries affected by fragility, conflict, and violence, but in many cases these factors can be anticipated and internalized in project designs.

The Bank Group has addressed gender norms through various strategies depending on the circumstance. These strategies include disguising sensitive interventions within standard ones, sensitizing communities to activities that challenge traditional gender norms, not openly challenging gender norms but working through them, and in a few cases, transforming gender norms directly.

The awareness and capacity of implementing partners to address gender inequalities vary across countries and projects but are generally low.

This chapter discusses the main factors that have constrained or enabled transformational change in supporting WGEE and addressing GBV in FCV countries. Transformational change is change that is relevant, inclusive, deep, sustainable, and scalable. The evaluation identifies four main groups of factors that impact, negatively or positively, individual projects and the World Bank Group’s approach as a whole: the prioritization of WGEE and GBV issues; the use of financial and human resources and capacities; the modalities of engagement, collaboration, and coordination with stakeholders; and the contextual factors in FCV countries.

Prioritization of Women’s and Girls’ Economic Empowerment, Gender-Based Violence, and Gender Inequalities

Addressing gender inequalities related to WGEE and GBV is rarely a priority for the Bank Group when addressing poverty and fragility. Bank Group documents often warn against the negative impact that gender gaps have on growth, poverty, and fragility. However, interviews suggest that gender inequalities are often considered by Bank Group staff as just another priority that must compete with many others. This is also indicated by how frequently country strategies identify gender as a “cross-cutting issue” without specifying which particular gender issues or gaps pertain to the strategy’s priority areas. Among the 15 country strategies analyzed for the six country case studies, 10 strategies defined gender as a cross-cutting issue. This is not necessarily an incorrect approach: gender inequalities affect and are affected by all development issues and require coordinated cross-sectoral interventions. It is also commonly accepted: gender is integral to each of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (UNDP and UN Women 2018; UN Women 2018b; UN Women, Women Count, and UN 2022), and cross-cutting approaches are used by other international financing institutions (World Bank 2015d). In the analyzed Bank Group country strategies, gender issues are not explicitly identified and prioritized but are instead sprinkled across pillars and the country portfolio, as also highlighted by the gender strategy Mid-Term Review (World Bank 2021f).1 Strategy documents commonly advocate to “include” or “pay attention to” women and, less commonly, include gender elements in human capital, infrastructure, social protection, or health projects. What is missing in these strategies is an explicit prioritization to reduce gender inequalities and tackle related issues including WGEE and GBV, and defined, coordinated actions to address them.

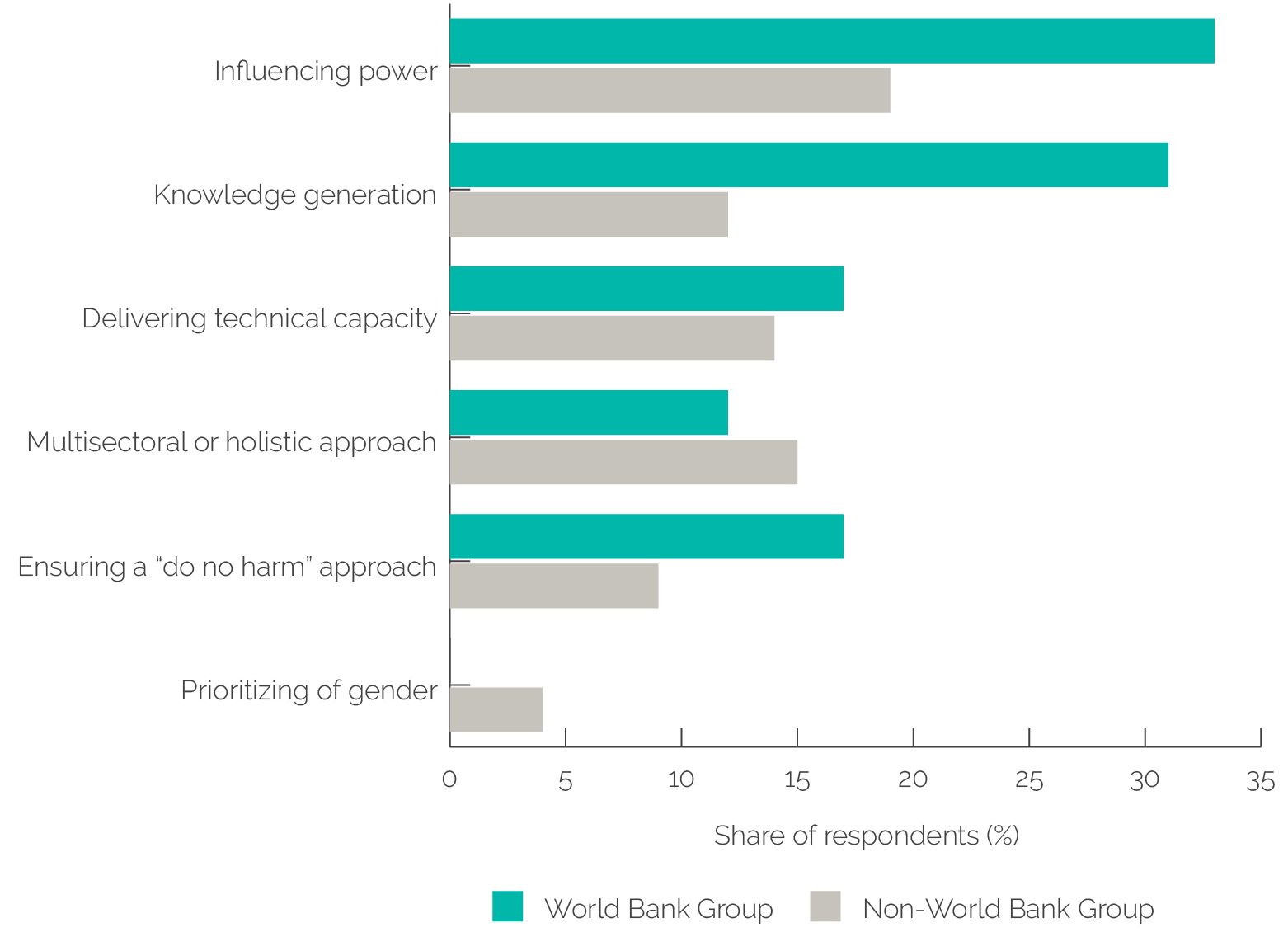

Most key informants believe that the Bank Group could be more impactful in supporting a country gender agenda if it used its multiple strengths for this purpose. When asked to indicate the comparative advantage of the Bank Group in supporting WGEE and addressing GBV, almost none of the key informants outside the Bank Group stated that it prioritizes gender in the country engagement—and no Bank Group staff did (figure 4.1). At the same time, the majority of Bank Group key informants expressed the opinion that the Bank Group has a key role to play within countries in “moving the needle” on gender issues because it has strong influencing power and the financial capacity to go to scale. Moreover, many Bank Group staff indicated that the institution has the technical capacity to provide “development solutions,” produce high-quality analytical work, and identify lessons learned on gender from operational experiences in different countries. Similarly, external key informants referred to the potential but untapped Bank Group ability to use its financial influence and negotiate with governments to bring attention to gender issues; they consider that the Bank Group has the financial, technical, and reputational weight to support the gender agenda in the country, but it misses the opportunity to do it. In the words of a key informant in Burkina Faso: “Organizations like the World Bank can influence the government because they lend money to it. They can pressure it to apply laws and adopt gender budgeting.”2

Supporting WGEE and addressing GBV have not been Bank Group priorities in policy dialogues and advocacy, but recent development policy operations (DPOs) are paying more attention to WGEE. The Democratic Republic of Congo CPF (2022–26) recognizes that policy dialogue can persuade countries with fragile and conflict-affected situations to reduce gender inequalities (World Bank 2022d). Yet, there are very few concrete examples of policy dialogues pushing for WGEE or for GBV prevention and response; 94 percent of Bank Group key informants said that gender-related policy dialogue was either absent or narrowly focused on specific projects or activities. One example mentioned by the key informants was dialogues with the government of Burkina Faso to institutionalize a mobile childcare approach—the focus was exclusively on a very specific activity (mobile childcare), not on broader themes, such as the unequal division of labor between men and women, among others. Nevertheless, a few recent DPOs include actions and indicators on WGEE. In the Solomon Islands, two recent DPOs (the First and the Second Solomon Islands Transition to Sustainable Growth DPOs) acknowledge that women-led firms are more exposed to and impacted by corruption than men-led firms, but neither DPO has any gender-specific intervention other than mandating that two of five positions on the Independent Commission Against Corruption be filled by women. In the two recent Burkina Faso DPOs, the Bank Group negotiated with the government to include indicators that measure the impacts of government reforms promoting the economic empowerment of vulnerable women.3

Figure 4.1. Key Informants’ Opinions on the World Bank Group’s Potential Comparative Advantage

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: The number of World Bank Group staff is 42; the number of non–World Bank Group key informants is 95. The categories are not mutually exclusive.

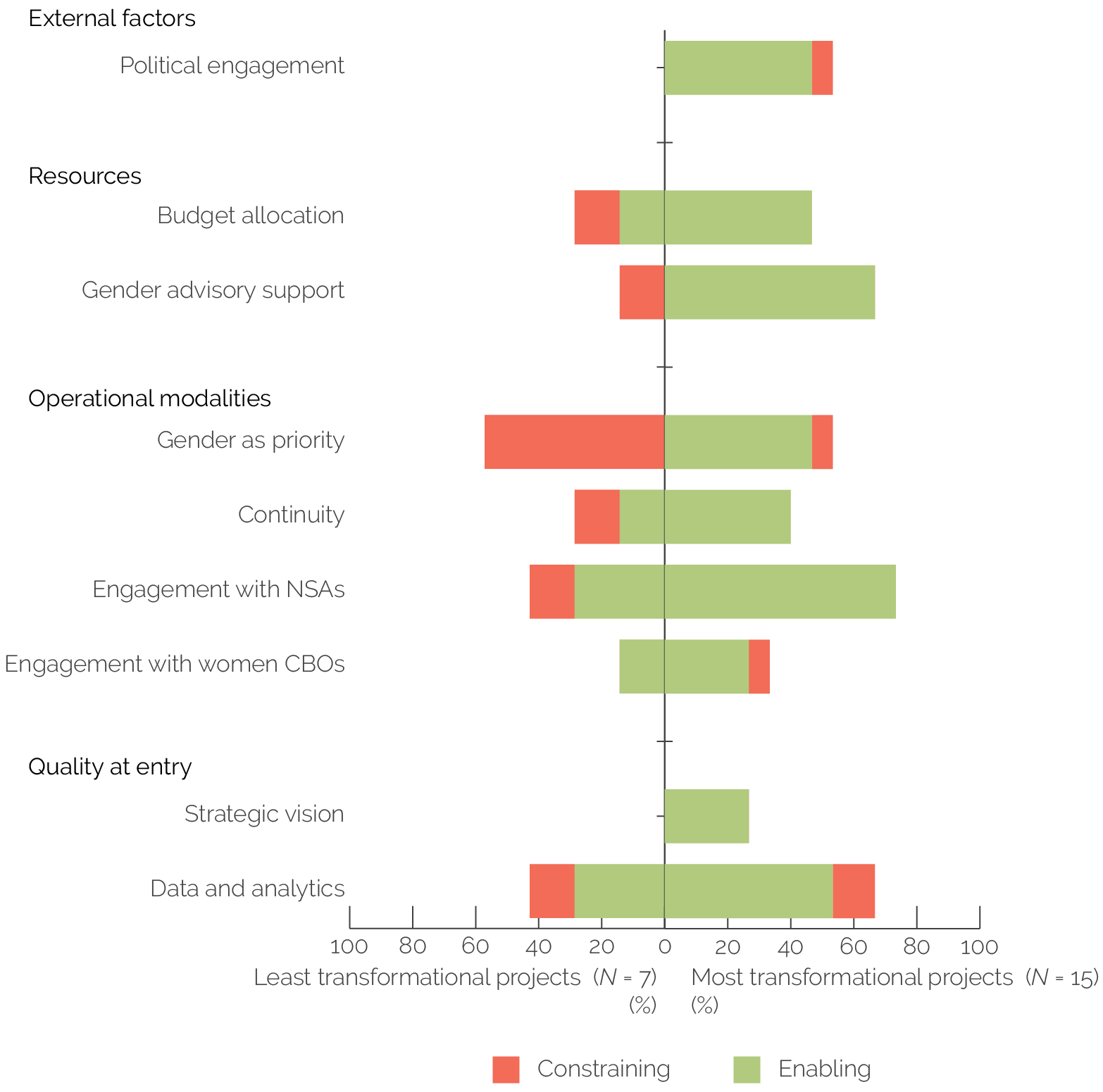

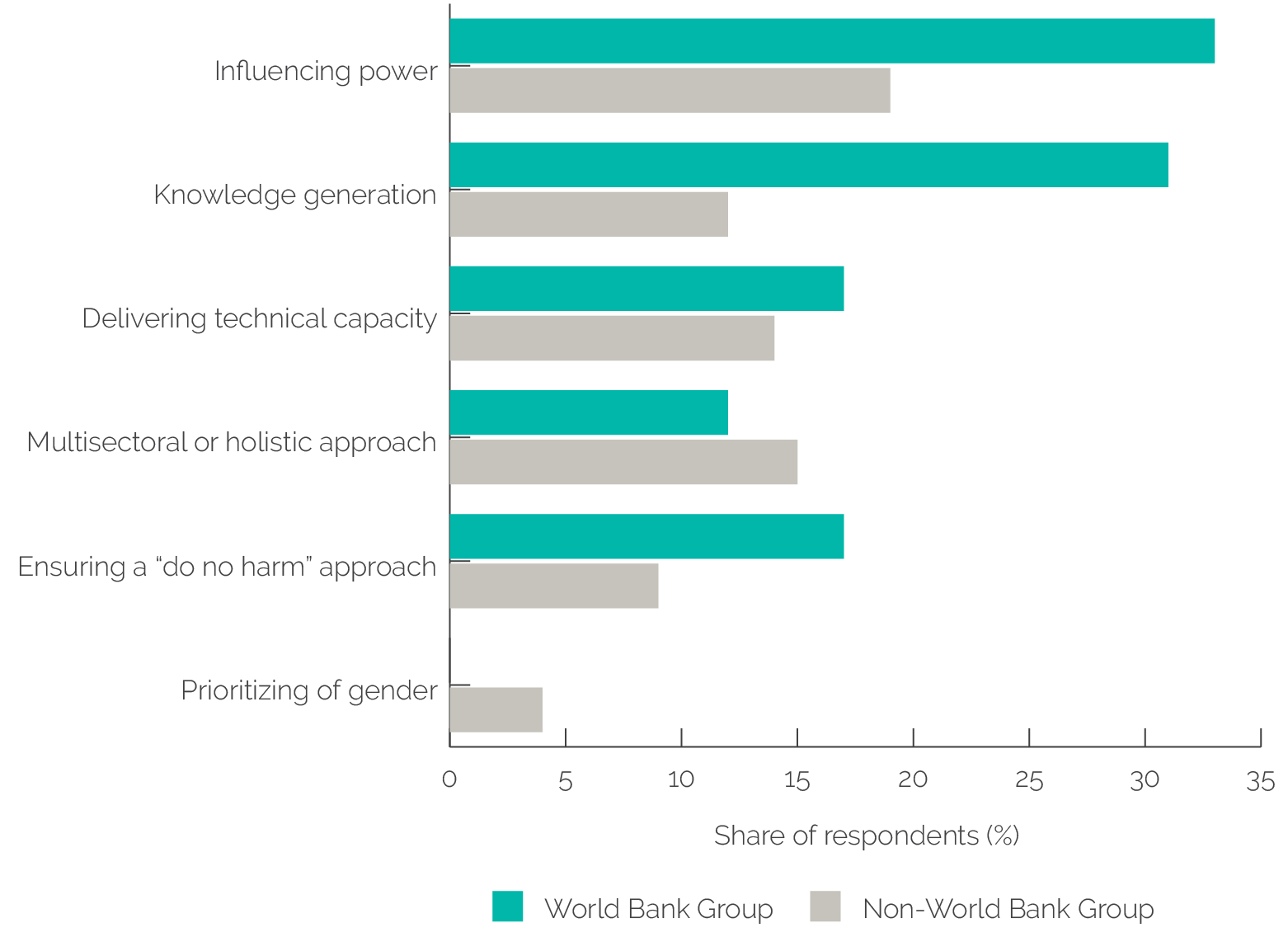

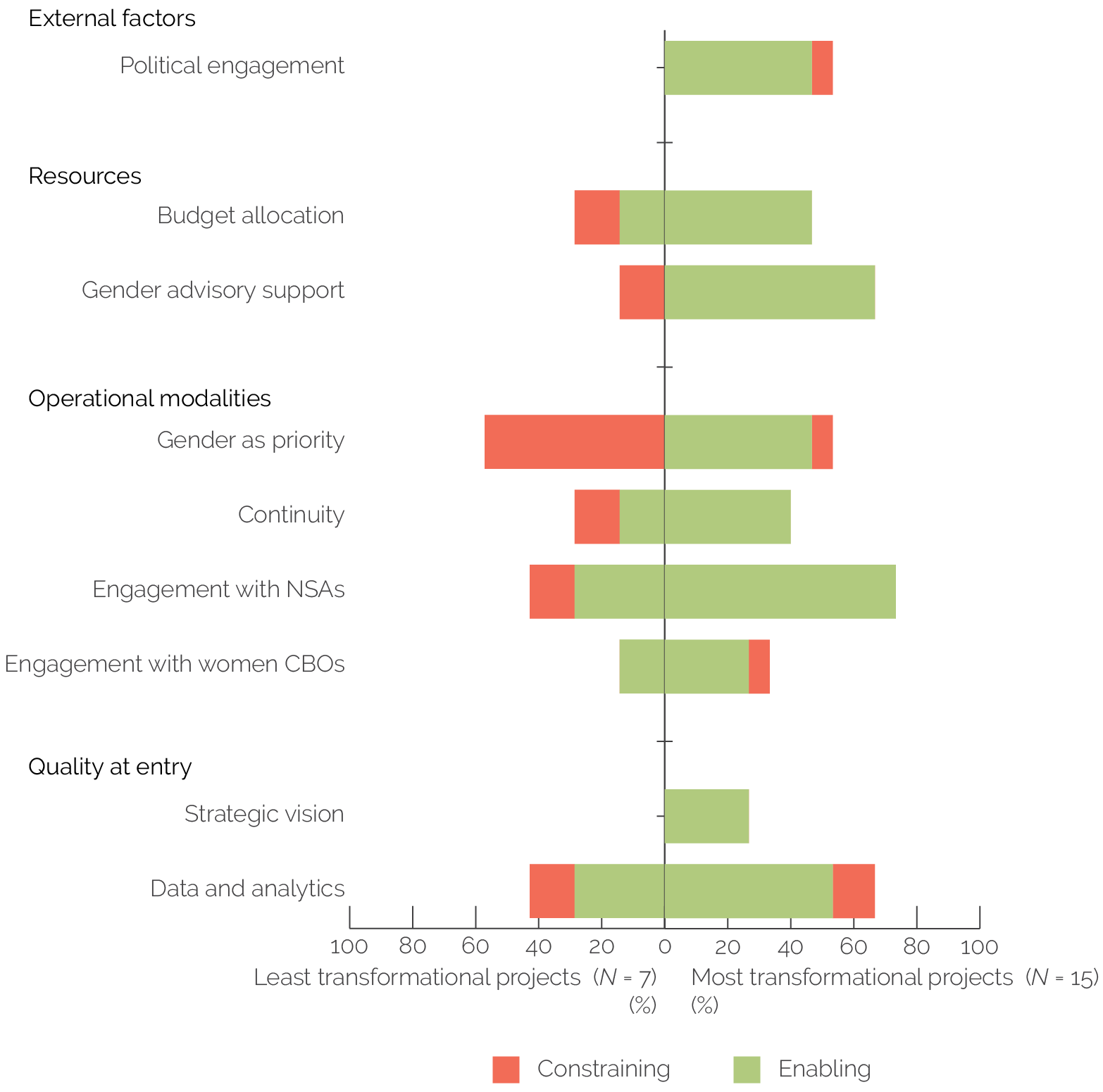

Prioritizing WGEE and GBV in non-stand-alone projects can enable transformational change. The analysis of project-level enabling and constraining factors indicates that projects with greater transformational potential prioritized WGEE or GBV in designs (figure 4.2). This is also true of non-stand-alone projects—that is, those that were not designed to explicitly promote WGEE or address GBV but mobilize gender skills, financial resources, and analytical expertise to this end. Examples of non-stand-alone projects designed to enable transformational change are the ALBIA and the Regional Sahel Pastoralism Support Project.

Financial and Human Resources

Allocating adequate financial and human resources is necessary to promote transformational change in WGEE and GBV. Projects that recognized their potential to support WGEE and address GBV and allocated adequate resources to this end were more likely to achieve transformational change in WGEE and GBV. Figure 4.2 shows that the “best” projects were those more likely to secure budget and gender advisory resources. Figure 4.3 shows that sustaining resources and staff awareness during implementation is critical to transition from a design’s transformational potential to achieving transformational change. Some project designs promoted WGEE without dedicated budgets for addressing women’s needs, constraints, and expectations. As a result, these projects had trouble involving women and supporting their economic empowerment. A few of these projects learned from this mistake and allocated additional financial resources for WGEE activities in their second phase or additional financing phase. For example, the Regional Sahel Pastoralism Support Project in Chad did not produce strong results because there was no dedicated budget for WGEE. The second phase filled this gap and allocated resources to a specific component that economically empowered women and youth pastoralists.

In some cases, the increased demand that the project generated was too high for the project to satisfy. Several projects generated more demand from potential beneficiaries than their budget could satisfy. This made it impossible for the project to deliver services to all in-need persons and created frustration among many women and girls who were excluded. Some projects required a lottery to select who would receive the services, which ultimately excluded beneficiaries (this is what happened in the Burkina Faso Youth Employment and Skills Development Project’s labor-intensive public works component). The solution adopted by FIP (also in Burkina Faso) was to divide the budget among all subprojects proposed by women’s groups, but as a result, the budget was sometimes too thin for certain subprojects, such as those that supported income-generating activities, to operate effectively.

Figure 4.2. Factors Enabling and Constraining the Transformational Potential of Worst and Best Project Designs

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: “Least transformational” projects are defined as those with no transformational element reaching the score 3 (that is, the minimum threshold for the transformational element to be considered significantly present). “Most transformational” projects are defined as those with at least three transformational elements reaching the score 3. Project rating criteria are described in detail in appendix A. CBO = community-based organization; NSA = nonstate actor.

Figure 4.3. Factors Enabling and Constraining the Achievement of Change for the Worst and Best Project Designs

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: “Least transformational” projects are defined as those with no transformational element reaching the score 3 (that is, the minimum threshold for the transformational element to be considered significantly present). “Most transformational” projects are defined as those with at least three transformational elements reaching the score 3. Project rating criteria are described in detail in appendix A. NSA = nonstate actor.

The World Bank and IFC’s gender skills and guidance were key factors for the projects that best promoted WGEE and addressed GBV in their designs. Figures 4.2 and 4.3 show that a project’s capacity to produce transformational change in GBV and WGEE and the ability to tap into specialized gender advisory support and skills are highly associated. The IFC’s MGF in the Middle East and North Africa, for example, strongly benefited from the provision of technical gender experts. This was also the case with the Republic of Yemen Emergency Electricity Access Project, whose project team included a gender adviser and a sectoral expert with gender expertise and ensured that gender issues were integrated into the project design. The World Bank’s regional gender agenda in the Sahel (which included the SWEDD project) also invested significantly in technical expertise and analytical work on gender. The IEG’s gender strategy Mid-Term Review (World Bank 2021f) confirms that gender expertise is essential for supporting task team leaders (TTLs), project leaders, investment officers, and practice managers. In particular, the Mid-Term Review noted the shortcomings from not having enough staff expertise on GBV and FCV, leading to designs that were not gender relevant.

The World Bank’s gender experts rarely work in field offices, which limits field staff and partner access to regular, quality, and context-knowledgeable gender expertise. Moreover, key informants remarked that the World Bank Group seldom participates in national gender events or gender coordination groups because the Bank Group has no local gender focal point. By contrast, when the World Bank Group’s gender expertise in FCV countries has been ample and continuous, it improved the quality and coordination of gender work. For example, interviews indicate that the presence of a gender focal point in the Bank Group’s Solomon Islands country office until 2014 facilitated consultations with civil society and policy dialogues with the government on gender issues.

Knowledge of gender issues among World Bank technical experts in Global Practices is uneven and generally weak. In interviews, some Global Practice staff showed a high level of knowledge, awareness, and sensitivity on gender issues. However, many FCV and sectoral experts demonstrated an insufficient knowledge of analytical frameworks and operational approaches to gender equality, WGEE, and GBV. For example, several TTLs misunderstood what “doing gender” (as they called it) means. Many TTLs believed that tracking and reporting the percentage of women beneficiaries was sufficiently addressing gender inequalities. Similarly, TTLs and some Country Management Unit staff did not understand why FCV countries required a tailored gender approach despite abundant evidence showing the need for this. As shown in figure 4.3, staff skills and awareness were highly associated with the projects remaining transformational during implementation. Many external informants confirmed the perception that the Bank Group lacked strong gender knowledge, saying that the Bank Group had “high technical capacity to provide development solutions,” but only one external informant said that the Bank Group had good “gender expertise.”

Bank Group staff also demonstrated a limited understanding of gender-FCV dynamics. Most staff interviewed for this evaluation described FCV as “conflict,” but failed to conceptualize the “fragility” and “violence” aspects and their interplay with gender inequalities. Two interviewees gave the examples of providing cashless transfers to avoid violence against women and including female IDPs as beneficiaries, whereas others stated that their projects were not in areas with active conflict—hence, the issue was nonexistent. The staff’s limited knowledge of these dynamics helps explain the limited combined gender-FCV relevance in projects and strategies.

It was common for TTLs to not understand the difference between providing GBV safeguards in projects and addressing GBV as a countrywide problem. The World Bank introduced the GBV–sexual exploitation, abuse, and harassment action plan (World Bank 2017c) in 2018 to safeguard against World Bank projects unintentionally contributing to GBV. The confusion between the safeguard approach and the countrywide approach was evident in interviews. Many Bank Group staff and implementing partners said that the GBV–sexual exploitation, abuse, and harassment action plan was addressing GBV, without realizing the different goals of a “do no harm,” safeguard approach and an integrated, countrywide approach to prevent and respond to GBV as a systemic issue.

Modalities of Engagement, Collaboration, and Coordination

Internal coordination across project teams is weak and is hindered by weak accountability mechanisms and project delivery incentives. The Bank Group’s incentive structure does not foster, and often hinders, collaboration across project teams, according to interviews. Bank Group staff said they were aware of the need to collaborate across sectors over a long-time horizon to address gender inequalities; however, staff still tended to “work in silos.” A TTL described the challenge: “Addressing gender issues cannot be done at the sectoral level. . . . It needs to be a coordinated approach. We need to work on several issues together—entrepreneurship, legal frameworks, childcare, demographics, health. . . . We try to work with others, but at the end of the day, we have to deliver our project.” Another TTL said: “Cross-sector collaboration is very important. GBV issues cannot be approached from only the health sector if we want to provide holistic support. We have so many entry points on gender, but we do not coordinate on all of them. It’s a pity! . . . It also has to do with staff’s bandwidth. Staff are overburdened and can often only do the bare minimum; so, finding project synergies is always last on the list.” It is also clear, as the gender strategy Mid-Term Review notes, that the main World Bank mechanism to monitor the gender strategy’s implementation—the gender tag—is a project-level tool and “creates incentives to focus on individual projects, rather than promoting a country-driven approach” (World Bank 2021f, 26).

Silos can be broken, although this is mostly left to an individual’s initiative. There are some good examples of internal coordination to address gender inequalities, but they strongly rely on the personal initiative of the TTLs. For example, during the preparation phase of one project, one of the TTLs proactively mapped the other Human Development projects that the World Bank was implementing in the same geographic areas, and which projects the TTL could collaborate with to build synergies to address GBV.

Coordination and collaboration among the Bank Group and external stakeholders on WGEE and GBV increase the likelihood of transformational change. Such collaboration allows an integrated approach to supporting WGEE and addressing GBV, whereby each stakeholder contributes to specific issues, covers different geographical areas, and targets different beneficiary groups. The involvement of multiple local stakeholders also ensures broad and effective ownership over interventions (World Bank Group 2020). The Bank Group has long recognized the benefits of establishing strong synergies and joint mechanisms among various interventions to assist vulnerable groups and close gender gaps (World Bank Group 2020). Figures 4.2 and 4.3 show that a good engagement with nonstate actors and women’s grassroots organizations is indeed important for transformational change.

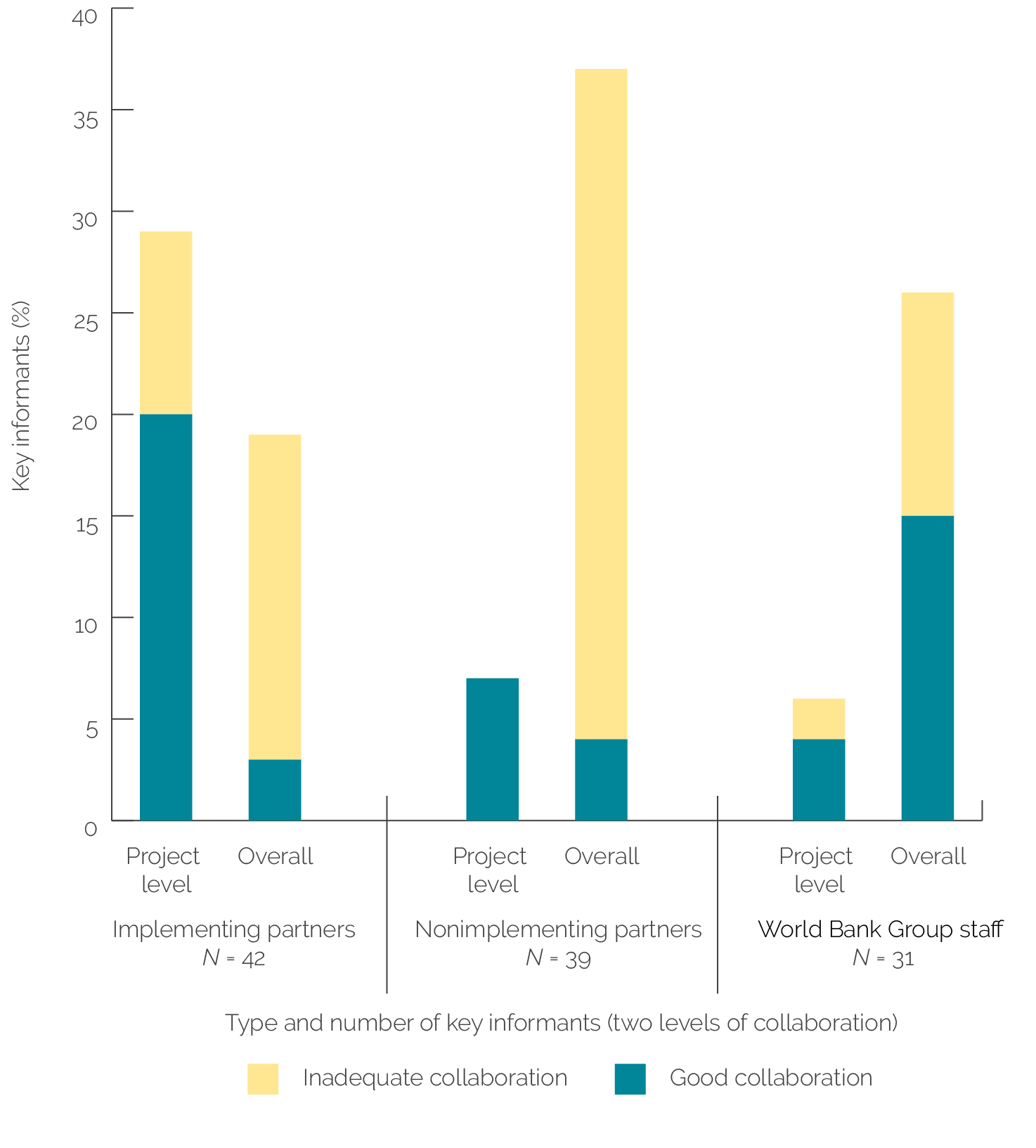

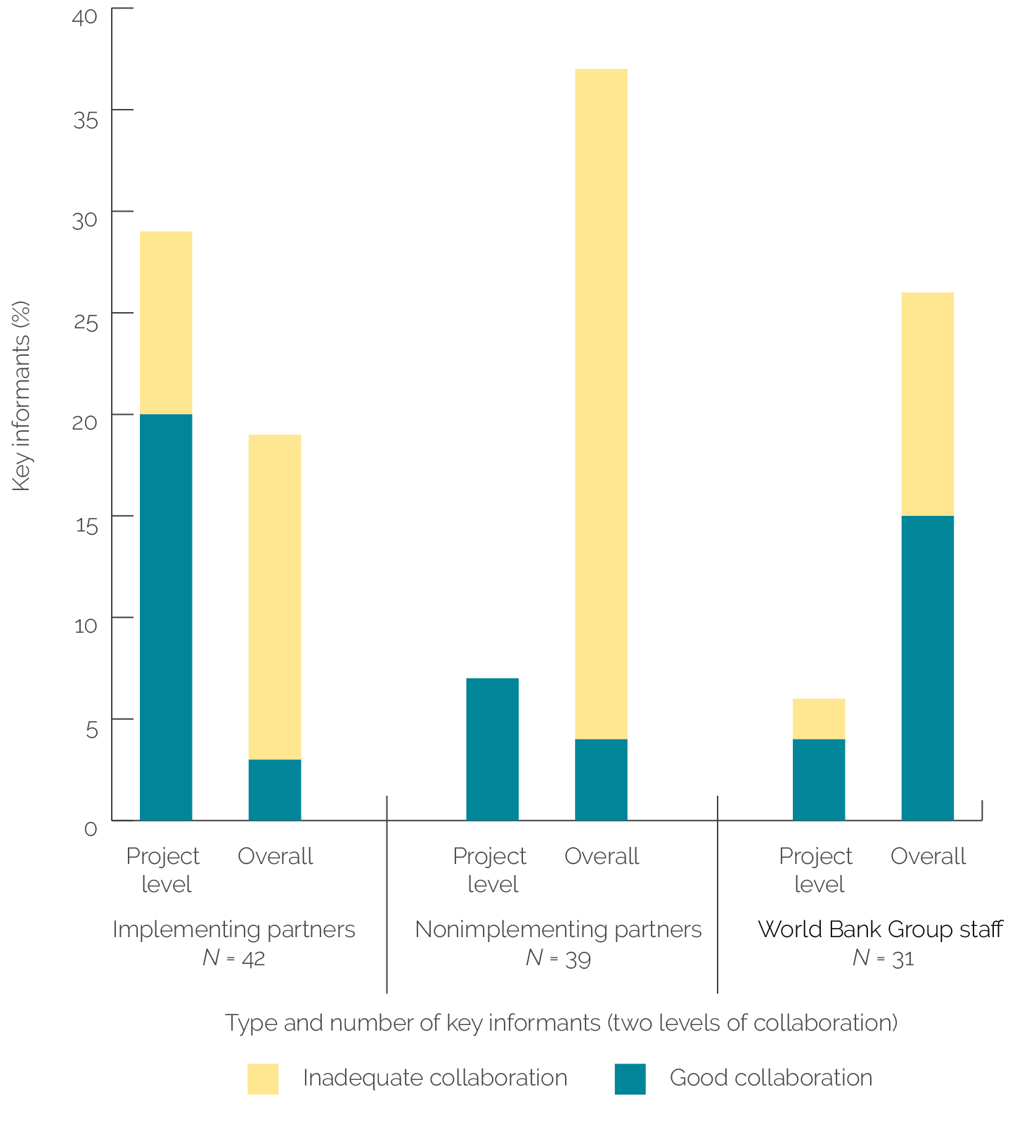

The Bank Group’s coordination and collaboration are strong with implementing partners on specific projects but are weak with nonimplementing partners. These nonimplementing partners include donors, women’s rights organizations, NGOs, and INGOs. Figure 4.4 shows that 20 of 29 implementing partners (mostly government counterparts) expressed a positive opinion of the quality of the Bank Group’s collaboration at the project level. However, only 3 of 19 implementing partners expressed a positive opinion of the Bank Group’s collaboration on the broader gender agenda. By contrast, the majority (33 of 39 or 85 percent) of nonimplementing partners said they did not collaborate at all with the Bank Group on the country’s gender agenda or were dissatisfied with the quality of that collaboration. This group included stakeholders from women’s rights organizations who are leaders in WGEE and GBV but reported they were not even involved in consultations with the Bank Group on its activities. Respondents from INGOs (80 percent) and donors (80 percent)—not shown in the figure—also expressed dissatisfaction with the quality of the Bank Group’s gender coordination in their countries. They said that the World Bank often leads coordination among donors and other stakeholders on other sectoral issues, but not on gender issues; nor does the Bank Group raise gender issues in these other sectoral coordination groups. In interviews, key informants stated that this collaboration was hindered by the lack of formal, institutionalized mechanisms and the different mandates and operational modalities of the Bank Group and its partners.

The World Bank Group’s collaboration with the ministries and other government institutions in charge of gender issues has also been weak. Four of nine government officials (44 percent) who were nonimplementers, including the ministry and other government institutions in charge of gender issues, reported having little or no collaboration with the Bank Group. Interviews also suggest that the ministry in charge of women and gender equality issues was not regularly involved. However, the Bank Group occasionally advocated for stronger collaboration with the ministry in charge of women and gender equality, although this was not common. For example, in Burkina Faso, the Ministry of Women and Gender is the implementing partner in the Financial Inclusion Support Project. A Bank Group key informant involved in the project explained that this involvement was a result of policy dialogues: “In the discussions, it was clear that there cannot be a financial inclusion project without addressing women’s inclusion. On the World Bank side, in terms of advocacy, we had analytical work to highlight gender gaps. In our advocacy process, we convinced the Ministry of Finance that we will not reach this objective if we do not bring in the Ministry of Women and Gender.”

Figure 4.4. Opinions of Key Informants on the World Bank Group’s Performance in Coordinating, Establishing, and Leading Partnerships to Address Gender Inequalities

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: The categories are not mutually exclusive.

A substantial share of World Bank Group staff (two-fifths) described their collaboration with stakeholders on gender as insufficient. Figure 4.4 shows that over half (58 percent) of the Bank Group staff who expressed an opinion in interviews said that the Bank Group collaborated well with external stakeholders on the gender agenda. However, a sizable share (42 percent) recognized that the Bank Group is not doing enough to collaborate. As one Bank Group key informant stated: “On many levels, collaboration is project by project. There is weak coordination. We could have done more and better.”

The World Bank rarely participates in donor coordination groups on gender and GBV subclusters. The World Bank often leads the coordination among donors and other stakeholders on many issues, but not on gender, and it tends to not raise gender issues in these other coordination groups. Key country-level informants from gender coordination groups and GBV subclusters reported that the World Bank is not a member.4 Many of them wished that the Bank Group participated because of the key role it can play in sharing information, lessons learned, and expertise; coordinating interventions; and participating in policy dialogues. A member of a development partner’s gender group said: “The [World] Bank should work with the other partners. Nobody knows what the [World] Bank is doing. They should not remain isolated. The [World] Bank is a multilateral partner, and it has expertise on economic issues. It could guide other partners, for example, on effective support for the economic empowerment of women.”5

The Bank Group rarely collaborates with donors on improving the enabling environment for gender equality, although there are some successful examples. In Lebanon, the MGF provided technical assistance to partners advocating for a law, which eventually passed, on workplace sexual harassment. However, in many other cases, the Bank Group missed opportunities to support gender equality through existing platforms, processes, and key actors and instead created parallel initiatives with similar goals. For example, the SWEDD established a regional legal platform, with a local branch in each target country, to analyze and propose improvements to each country’s legal system with respect to sexual and reproductive health, girls’ education, and GBV. This platform did not involve some key women’s rights organizations, INGOs, and donors already working toward improving the country’s legal framework and did not coordinate with other existing platforms, such as the road map to end child marriage in Chad and the action plan to end child marriage in Burkina Faso. Similarly, in Burkina Faso, the SWEDD did not coordinate with the government’s existing gender budgeting initiative when supporting the integration of the demographic dividend in public budget allocations.

The Bank Group’s consultations with CSOs, including women’s rights organizations, are not systematic and do not typically inform project designs. Consultation with civil society is one of the main channels for the Bank Group to engage citizens and build inclusive ownership over projects. However, the evaluation found that the Bank Group’s consultations with these actors are not consistent and are particularly weak with women’s rights organizations.6 The Bank Group regularly consults civil society when developing projects, country strategies, and knowledge products, but it does not systematically document the outcomes from these consultations—confirming a finding from IEG’s Engaging Citizens for Better Development Results evaluation (World Bank 2018g). The desk review, for example, indicates that two of nine RRAs, three of six SCDs, and only the Republic of Yemen Country Engagement Note out of 15 country strategies specifically mention consultations with women or women’s organizations. Sometimes Bank Group consultations occur but fail to inform project designs. A TTL explained: “One element is the project preparation process that informs the project ideas, and then we have the World Bank process where we have to simplify, simplify, simplify. We end up doing business as usual.”

Top-down planning without meaningful consultations with key stakeholders, including women and girls, can undermine projects that promote WGEE or address GBV. For example, in the first phase of Burkina Faso’s Agricultural Productivity and Food Security Project, the project team did not consult potential female beneficiaries on the type of equipment needed for processing food. As a result, the equipment did not correspond to the needs and operating capacities of the beneficiaries. This mistake was rectified in the second phase of the project, which involved women in choosing the equipment. In Burkina Faso, the SWEDD trained young women and adolescent girls to produce liquid soap as an income-generating activity. However, the implementing partner chose liquid soap without consulting beneficiaries, who felt that there was no market for it in their community because people preferred solid soap. Moreover, the ingredients were hard to source locally and expensive to deliver to the community. As a result, the liquid soap activity was not profitable and had to be discontinued. In another locality, the safe spaces to develop skills for out-of-school adolescent girls and young women struggled to involve adolescent girls because they were working in the city as domestic workers. These adolescent domestic workers are among the most vulnerable girls in Burkina Faso and are at high risk of unwanted early pregnancies, sexual violence, and child marriage. The SWEDD would need to be flexible to identify other ways to reach this target group (for example, through conditional cash transfers combined with skill development). Identifying activities with local communities, women, and girls, rather than with central government authorities, would mitigate many of these targeting challenges (box 4.1).

Engaging with opinion leaders is necessary for advancing WGEE and preventing GBV. WGEE and GBV initiatives are sensitive endeavors, and the role of opinion leaders as allies on this agenda is critical. According to Le Roux and Palm (2021), religious and traditional leaders can influence social norms that either enable or hinder progress in addressing GBV. Opinion leaders have the influence to either affirm or resist positive gender norms at the community level (Cislaghi 2019; ODI 2015; Rowley and Diop 2020). The SWEDD team recognized this and made engagement with religious and traditional leaders a project pillar at the regional, national, local, and community levels. A key informant in Chad stated: “Advocacy toward religious leaders is not enough; we must support religious leaders. We have developed a document based on the texts of African religion and tradition, we have trainers who build the capacity of leaders to show that religious precepts are not against family planning and are against [GBV]. From that moment, leaders got involved and delivered this message in mosques, churches, and royal courts.”7 Engagement with religious leaders also supported peer learning across countries: “The discussions with religious leaders in Morocco have allowed religious leaders in Chad to understand that interpretations of Islam can be flexible.”8

Box 4.1. Burkina Faso: The Effectiveness of Bottom-Up Approaches in Promoting Women’s Economic Empowerment and Enhancing Women’s Voice and Agency

In the Burkina Faso Forest Investment Program—Decentralized Forest and Woodland Management Project, the bottom-up approach was effective in supporting women’s economic empowerment and enhancing women’s voice and agency in local management of natural resources. The project organized participatory need assessments at the community level to define priorities and activities to support and significantly involve women in this process. The municipalities financed those activities, including those proposed by women. The projects also funded microprojects proposed by grassroots organizations, including women’s groups; 48 percent of the grants went to women to support their economic activities. Involving women in consultations, training, and discussions about land rights and securitization and providing financial and technical support to women’s groups increased both women’s economic empowerment and their voice and collective agency. Women became increasingly vocal in community meetings, women’s cooperatives became stronger, and women producing shea butter successfully advocated for securing land for shea nut collection.

This bottom-up approach was combined with a top-down mandatory quota of women in local governance committees (such as the forest management committees and the grievance management committees), which were also supported by the project. However, the women’s presence in the local committees was not monitored, and it consisted only of “at least” one female leader. One woman in a committee of 7–12 men was not enough for women to influence decisions and keep the other women informed. Moreover, without a strategy to increase the awareness and capacity of institutional actors to promote women’s participation and gender equality, this institutional mandate could not make the local institutions more sensitive to women’s needs and gender equality. As a key informant highlighted: “What has been missed is the institutional change. The project did not have an overall strategy to change institutional actors. There could have been advocacy at the institutional level with the ministry and local authorities to make actors more aware of gender issues and how to address them.”

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

The World Bank has increasingly involved men and boys as change agents to transform gender norms, but this involvement is still limited. Projects that engage men, boys, and male opinion leaders to adhere to positive ideals of masculinity are more likely to enhance male acceptance of WGEE and rejection of GBV and promote more equitable gender roles and relations (Désilets et al. 2019; Doyle and Kato-Wallace 2021; IRC 2019; Promundo 2012; Promundo and UN Women 2017; Ruane-McAteer et al. 2020; Slegh et al. 2013; Van Eerdewijk et al. 2017; World Bank 2015d). The Bank Group’s gender strategy (World Bank 2015d) recognizes that engaging men and boys is a priority in FCV-affected countries. Many key informants highlighted that men and boys are key agents for transforming gender relations. For example, a female leader involved in the SWEDD in Burkina Faso stated that “working with men is necessary to change their mentalities, so that they support women, and they do not shun their responsibilities.”9 Men are also the best role models for other men, as a religious leader in Burkina Faso explained: “It is easier for men to convince other men to allow women to do things.”10

Several projects engaged men and boys to lessen their resistance to change, but details on these initiatives are sparse. Few projects had structured and deep approaches for engaging men and boys. The SWEDD, for instance, supports the creation of men’s and boys’ clubs (also called “husbands’ and future husbands’ schools”) to promote positive masculinity in the target communities. Likewise, the GBV Prevention and Response Project in the Democratic Republic of Congo relies on two approaches (Start, Awareness, Support, and Action and Engaging Men through Accountable Practice), depending on the community, to engage men and boys. According to the Project Appraisal Document (World Bank 2018e), this project also supports male survivors of GBV and discrimination, but the Project Appraisal Document does not provide details on how it intends to do this.11 This example aside, no other analyzed project explicitly targeted men and boys as survivors of gender-based discriminations and violence. In addition, the evaluation did not find any project or piece of analytical work that addressed GBV and discrimination against people identifying as lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, intersex, and queer (and all other gender and sexual orientations) in these countries.

IFC’s engagement with the private sector to promote safe and gender-equal workplaces has shown promising results but did not involve governmental institutions or women’s organizations in designing these measures beyond initial consultations. In the Solomon Islands, IFC’s Waka Mere initiative (part of the IFC Pacific WINvest advisory services project) supported 15 large firms in advancing gender equality at the workplace by adopting policies and practices to prevent and respond to sexual harassment and other forms of GBV and promote women’s leadership and access to traditionally male jobs. Waka Mere increased the employees’ and employers’ perception of safety and comfort at the workplace and the proportion of women in positions of leadership and traditionally male jobs (for example, drivers; IFC 2019b). Two weaknesses that were highlighted by key informants were the project’s unduly short duration (two years) and the lack of involvement of the Ministry of Women and local women’s organizations in the project’s planning. That said, a positive development was the interest expressed by the government of the Solomon Islands to adopt the lessons from Waka Mere for the public sector.

Contextual Factors

Contextual factors make it difficult for the Bank Group to achieve transformational change in GBV and WGEE in FCV countries. FCV situations are, by definition, extremely risky environments. Fragility factors can hinder project implementation and dampen results. These factors also affect the size and accessibility of the private sector. The evaluation found four main factors that constrained the implementation of analyzed projects in FCV countries: (i) conflict dynamics and their consequences, such as insecurity and forced displacement; (ii) prevalent, unequal gender norms; (iii) the COVID-19 pandemic; and (iv) the weak capacity of implementing partners on GBV and WGEE issues.12 Figure 4.3 shows that most projects that produced significant levels of transformational changes were able to mitigate the negative impacts of FCV’s contextual factors.

Conflict Dynamics

Conflict dynamics undermined WGEE and GBV outcomes in the case study countries. In the past 10 years, the case study countries were affected by different conflict dynamics, which required different types of responses. For example, addressing the challenges from the Republic of Yemen’s long-lasting civil war required a different response than what was needed to respond to the breakout of conflict in Burkina Faso. In the Republic of Yemen, the open and protracted armed conflict imposed hard constraints on the overall effectiveness and sustainability of activities.

The World Bank Group managed situations of long-lasting conflict, such as in the Republic of Yemen, by combining several strategies. The Bank Group’s political neutrality has been a necessary condition for its operations in the Republic of Yemen. Moreover, the Bank Group made UN agencies its de facto client in lieu of a functioning government counterpart. The UN’s perceived political neutrality ensured that they could have access to areas controlled by various warring factions. The UN also had an established network of local partners—CSOs, community-based organizations, and INGOs—that were able to reach even more remote areas. The World Bank maintained this neutral posture even before the conflict broke out by working with two key local implementing partners—the Social Fund for Development and the Public Works Project—with impeccable records of political neutrality and a history of implementing successful social protection projects. Bank Group projects relied on community-driven approaches to plan and implement activities after highly inclusive and consultative processes tailored to the self-identified needs of these communities. Wherever possible, local and regional administrations were included in the process as well. With the largest projects, such as the Emergency Crisis Response Project and the Emergency Health and Nutrition Project, target communities were selected using methodologies that ensured project neutrality and inclusiveness. In dealing with gender issues, specifically GBV, the projects followed the approach already used by the UN and INGOs, which “hid” GBV activities within social protection and health interventions.

In Burkina Faso, the World Bank used innovative approaches to adapt to conflict dynamics, which allowed it to maintain support for WGEE and for GBV prevention and response. Armed violence erupted in northern Burkina Faso in 2015 and rapidly expanded to other regions of the country, negatively impacting several World Bank interventions. The conflict prevented local project staff and implementing partners from reaching target communities. It also disrupted basic services, displaced beneficiaries and local stakeholders, diverted public resources away from development, and increased the risk of armed groups gaining control over areas with activities focused on GBV, girls’ schooling, and sexual and reproductive health. The conflict also had differential impacts on women and girls, affecting their freedom of movement and access to health and education services. In response to the crisis, the World Bank adjusted its projects’ target localities to avoid conflict-affected areas, while maintaining support to conflict-affected populations. For example, the SWEDD’s implementing partners tracked forcibly displaced girls and continued to support their schooling and skills development in their new communities. The SWEDD also empowered local and community-based actors to assume more direct responsibilities in coordinating project activities and led project trainings and monitoring efforts remotely.

The Bank Group and its implementing partners responded with prudence, discretion, and flexibility to the attitudes of Islamic armed groups toward gender initiatives. In the areas of Burkina Faso affected by attacks from the Islamic armed groups, World Bank projects faced a new challenge: the extremists threatened people who proposed any gender discourse or initiative that was not aligned with their radicalized gender norms. An implementing partner described the threats received by fieldworkers who discussed sensitive gender topics in community meetings: “Insecurity limits expression and assemblies to convey messages. Certain topics expose fieldworkers to the risk of reprisals from armed groups. To mitigate the exposure of agents and communities to these groups, the messages are toned down.”13 Another implementing partner described the approach: “There were also villages where terrorists were a threat. They say that what we do in the safe spaces is contrary to their preaching, so we have to adapt the strategies. It is important not to make a lot of noise about the intervention. We asked the mentors in the villages to assess the threat. If a threat is identified, mentors must suspend the activities to not put the girls at risk. There are also some mentors who no longer facilitate the sessions in fixed spaces; they do them in the courtyard of the families in order not to draw attention.”14

Gender Norms

Gender norms constrained WGEE progress and GBV prevention and response in context-specific ways. Several key informants said that adverse gender norms constrained women’s access to services and participation in project activities.15 As a local INGO staff member in Chad explained: “Social norms are at the origin of everything. For example, it is not easy for GBV survivors to report cases of GBV, and even when it comes to the empowerment of women or women’s access to resources and decision-making power, efforts are stymied because of social norms. In some areas, social norms prevent women from expressing themselves.”16 In Chad, the Emergency Food and Livestock Crisis Response Project found it challenging to get young women to participate in trainings because many of these women are not permitted to travel alone, spend the night away from home, or be part of mixed-sex groups. In the Democratic Republic of Congo Great Lakes Project, the number of GBV survivors who received medical care was lower than expected, one reason being gender norms that discourage reporting and stigmatize GBV survivors.17 In the Republic of Yemen, the additional financing for the Emergency Electricity Access Project had to decrease the number of female borrowers for home solar systems because of gender norms restricting women from making financial decisions. As a result, only 15 percent of targeted women were able to purchase solar power. In the Solomon Islands, the Community Governance and Grievance Management Project aimed to improve women’s access to justice, including for GBV cases, by including female community officers in the community grievance mechanisms that mediated between local leaders, such as chiefs and elders, and the provincial and central government. However, only 2 of the 49 recruited community officers were women, with one resigning after getting married. The Implementation Completion and Results Report commented that this was the result of “perceived gender roles and expectations entrenched in communities. . . . [F]eedback from communities suggested several obstacles to hiring more women [community officers] and contributing to the imbalance. These relate to perceived gender roles in functions of communal authority, security risks women faced by having to deal with grievances relating to violence, and having to travel large distances throughout the day” (World Bank 2022f, 19).

The Bank Group and implementing partners used three main approaches to address gender norms—bypassing, sensitizing, and seconding. In interviews, Bank Group staff emphasized the importance of “understanding the context” to address gender norms. The first approach, bypassing, consisted of disguising or attenuating sensitive topics or activities. For example, in the Republic of Yemen, support to GBV survivors was not explicitly included in any project and was “hidden” within health interventions. In some contexts, SWEDD fieldworkers introduced sensitive topics prudently and indirectly. As the representative of an NGO said: “There is also the sensitivity of topics such as girls’ marriage. In some contexts, such as the Sahel, we cannot treat the topic directly.”18 The second approach was sensitizing the target populations, especially men and opinion leaders, to gender-related topics and activities, such as girls’ schooling, women’s skill development, and women’s economic empowerment. For example, before opening the safe spaces for adolescent girls’ and young women’s skill development, the SWEDD organized community meetings and, with the help of community leaders, asked fathers and husbands for their permission to invite female relatives to the safe spaces. The third approach, seconding, was to make GBV and WGEE activities consistent with traditional gender roles and support preexisting community women’s groups. For example, in Chad and Burkina Faso, projects supported agriculture value chains that were already dominated by women, such as milk, cassava, or shea butter value chains. This approach succeeded in increasing women’s incomes and fostering women’s participation without challenging traditional gender roles. Other projects have “seconded” gender norms that prevent women from working with or associating with men. For example, the Agricultural Productivity and Food Security Project and the ALBIA recruited female agriculture extension workers to work directly with female beneficiaries and organized consultations into separate gender groups when necessary. Similarly, in the Republic of Yemen, the Emergency Crisis Response Project recruited women officers and engineers to help reach out to women for consultations.

The World Bank also used deeper and longer-term engagements with local communities and key change agents to address harmful gender norms. This approach used various activities that targeted different groups. For example, the GBV Prevention and Response Project in the Democratic Republic of Congo and the SWEDD in the Sahel combined media campaigns with community-based initiatives to create discussion spaces to foster community dialogue, empower women and girls, and engage with men, boys, and opinion leaders on positive masculinity. This approach has been used by NGOs such as Tostan, with very positive results (box 4.2).

Box 4.2. Nonjudgmental, Community-Led, Empowering Approaches That Yield Major Change in Adverse Gender Norms: Lessons from Tostan and the SWEDD Project

Tostan is a nongovernmental organization operating in West Africa. Its approach, centered on community well-being, has consistently led to transformation of adverse gender norms and has proven very effective in preventing gender-based violence.a Tostan’s approach is nonjudgmental, inclusive, human rights based, and community led. The goal is to empower community members by providing communities with the instruments to discuss their own reality, identify their strengths and problems, and find ways to address them. It refrains from “attacking” their values and judging what is wrong and what is right. Rather, it provides the opportunity for communities to discuss a common vision of well-being and how this relates to human rights principles and deeply held values that include solidarity, peace, and nonviolence. This enables reframing of existing roles and behaviors, especially gender roles, from within. The approach has three main pillars: community classes, establishment and support of community management committees, and an organized diffusion process and training of decentralized government officials to cover entire districts. Community classes are led by a facilitator who encourages women’s participation and leadership, helps participants to define their shared values and identify their challenges, and equips them with knowledge and problem-solving skills to find solutions. The community management committees are tasked with putting into practice what was learned in the community classes. The organized diffusion process, led by class participants and community management committees to share their new knowledge and understanding within the community and in other communities in their social networks, amplifies the movement of social change.

Gender equality practitioners increasingly recognize that trying to change behaviors by transmitting top-down messages on “wrong practices” does not work; rather, adopting culturally sensitive and nonjudgmental approaches that enhance existing cultural values and empower communities to pursue their goals is the way to go. One member of a nongovernmental organization partner of the SWEDD reflected on this increased awareness: “Not everything should be given up in our culture. Good cultural practices have not been enhanced. . . . For example, stopping female genital mutilations is good, and we all welcome it; however, this practice also played a part in the initiation of young girls. Although fighting the harmful part, which is the mutilation, what shall be done to replace the initiation part where young girls receive information on sexuality and are prepared for having a family?”b Another interviewee highlighted that approaches to family planning need to be culturally sensitive and that change cannot be imposed: “During the training, leaders denounced a project that did family planning for 12-year-old girls, and they said that nobody wants a wandering woman; the leaders were on edge, and they had to be listened to because the change imposed is not change. . . . These kinds of discussions help to redirect the messages.”c Another key informant explained that a culturally sensitive and empowering approach means, in concrete terms, not imposing ready-made solutions but supporting the community to find its own way: “We have to work together, we have to think together, [and] we have to discuss the problem together; we do not have the solution—it is with them [the community] that we build the dynamics that must drive this transformation. . . . Gender is temporal, spatial, so it is with them that we are building together the possible solution for the fight against [gender-based violence].”d Dignity is at the core of culturally sensitive approaches to transform gender norms, as another key informant explained: “It is about stimulating an endogenous process in which men do not lose their dignity, thanks to the fact that the change is accepted by the community. . . . [The process needs] to maintain the dignity of the change agents. There are tasks that men ‘should not’ do; however, with the work we have done, [the man] will not feel embarrassed [and] will not be ashamed, and he maintains his dignity while doing this [traditionally ‘female’] task.”e

Community-led approaches are more effective in changing gender norms (Cislaghi 2019), but upgrading from a simple community-based approach to a community-led approach, in which the change is driven by the communities and the direction of change is decided by them,f is not easy because it takes time and requires skilled and embedded facilitators in the communities to support the process.

Source: Independent Evaluation Group, from key informant interviews in Burkina Faso and Chad.

Note: SWEDD = Sahel Women’s Empowerment and Demographic Dividend.a. An evaluation conducted in 2008 found that gender-based violence prevalence had dramatically decreased in participant communities (from 86 percent to 27 percent), and attitudes toward girls’ education, sex discrimination, intimate partner violence, and female genital mutilation had also remarkably improved. Participants also reported that gender relations improved, and gender norms had shifted (Diop, Moreau, and Benga 2008). More recent evaluations of the Tostan approach can be found at https://tostan.org/resources/evaluations-research.b. In French: « Ce n’est pas tout à abandonner dans notre culture. On n’a pas valorisé les bonnes pratiques culturelles. . . . Par exemple, l’abandon de la pratique de l’excision est bien et le souhaiteraient tous, cependant, dans cette pratique, il y’avait la partie relative à l’initiation des jeunes ; tout en combattant la partie néfaste qui est la mutilation, quoi faire pour remplacer la partie initiation où les jeunes filles recevaient les informations sur la sexualité et les préparent au futur ménage? »c. In French: « Dans la formation, les leaders ont dénoncé un projet qui a fait la planification familiale pour les filles de CM2 et ils ont dit que personne ne veut une femme vagabonde ; les leaders étaient sur les nerfs et il fallait les écouter car le changement imposé n’est pas du changement. . . . Ces genres de discussion permet de réorienter les messages. »d. In French: « Il faut se concerter, il faut réfléchir ensemble, il faut poser le problème ensemble, nous n’avons pas la solution, c’est avec eux que nous construisons la dynamique qui doit impulser cette transformation. . . . Le genre est temporel, spatial, donc c’est avec eux que nous construisons ensemble la solution possible pour la lutte contre les VBG. »e. In French: « C’est le fait de stimuler un processus endogène dans lequel les hommes ne perdent pas leur dignité, car le changement est accepté par la communauté. . . . La chose est faite pour maintenir l’agents du changement dans la dignité. Il y a des taches que les hommes ne doivent pas faire, mais avec le travail que on a fait, on arrive qu’il ne se sente pas gène’, n’a pas d’honte, il reste dans sa dignité pour faire ce travail. »f. Cislaghi suggests using Arnstein’s ladder of participation to understand the difference between community-based and community-led approaches. This ladder ranks the approaches of community-based development “from manipulation of community members to align their [behaviors] with practitioners’ views of what they should do (the bottom rung), to giving them full control of the intervention (the top rung). Community-led approaches, specifically, are at the top of the ladder. Here, community members themselves identify sociopolitical problems that matter to them, and develop and implement relevant, culturally sound solutions. In other words, in community-led approaches, transformative power is in the hands of community members, who make key decisions on aims and strategies of their collective development efforts” (Cislaghi 2019, 6).

Combining communication activities with interventions that generate tangible benefits for women and girls has been an effective strategy for changing adverse gender norms. For instance, the SWEDD strategy combines activities of communication with practical support to girls’ education, women’s and girls’ reproductive health and economic empowerment, and GBV case management. According to some key informants, this strategy helps in changing gender norms because women, girls, and their communities perceive that they derive a concrete benefit from the intervention and not just access to information and the ability to advocate for their needs. As a key informant said: “The SWEDD meets the real needs of the population. The beneficiaries are directly affected by the implementation. The support comes directly to the population.”19 Similarly, the Democratic Republic of Congo GBV Prevention and Response Project includes holistic support for GBV survivors and activities for community mobilization, behavioral change, and income generation.

COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic undermined some of the advances in WGEE and exacerbated GBV risks in FCV countries. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the risk of GBV increased (Mittal and Singh 2020; UN Women and UNDP 2022), including in FCV situations (UNHCR 2021; Vahedi, Anania, and Kelly 2021). For example, during lockdowns, women and girls were forced to stay in crowded households, which increased their vulnerability to intimate partner violence. Lockdowns also hampered GBV support services, which faced closures because of operational disruptions, resource shortages, or the fear of COVID-19 transmission (World Bank 2021f). The COVID-19 pandemic also affected WGEE because it exacerbated gender gaps in access to jobs and income and disproportionately increased women’s and girls’ unpaid work burden, including increased household work (UN Women and UNDP 2022; World Bank 2021f; World Economic Forum 2021). Women working in the informal sector experienced even sharper pay declines and losses in working days compared with their male counterparts. This loss of income coupled with limited access to social protection resulted in rising food insecurity, which affected women disproportionately (UN Women and UNDP 2022). These impacts were very noticeable in the case study countries. For example, in Chad, the World Bank estimated that COVID-19 disproportionately impacted urban women because of high female unemployment; a greater risk of GBV, especially intimate partner violence; decreased access to sexual and reproductive health services; and disruptions in schooling, which exacerbated education gender gaps (World Bank 2020a). In Lebanon, women’s economic vulnerability and unpaid care work increased dramatically, as did GBV against women, girls, and gender-nonconforming individuals.20 At the same time, marginalized women and girls—especially migrants, refugees, and older women—found it even harder to access support and services because they often lacked cell phones or other information and communication technology (UN Women and UNDP 2022).

COVID-19 negatively impacted WGEE support and GBV prevention and response activities. The pandemic disrupted field research and analysis, stakeholder consultations for project planning, and project implementation. A World Bank TTL in Chad stated: “During COVID-19, we could not work because everything was closed, and we could not do distance work because of internet access issues in the country. We tried to put some measures in place to help the government build a resilient system, but it is not easy because everything here goes slowly, including the procurement process.” Projects promoting girls’ education were also badly impacted by COVID-19: “There was a tremendous negative shock to girls’ education interventions in Burkina Faso. Girls lost learning and were more likely to be married off because they are considered an extra mouth to feed. As a result, child marriage increased. That has a clear negative impact on women and their empowerment.” In Lebanon, many women dropped out of Women Entrepreneurs Finance Initiative activities during the COVID-19 pandemic because they had to care for sick family members and children who were in lockdown as schools were closed. The pandemic also affected IFC’s support to the Al Majmoua microcredit program because loan officers were unable to physically collect or disburse loans. Moreover, several of the project beneficiaries had to shut down their businesses when workers contracted COVID-19.

Projects adapted to COVID-19 lockdowns through flexibility and more remote work, but remote support was not always possible or effective in FCV countries. In Lebanon, the profound crisis undermined the success of projects, even when they were able to adjust (box 4.3). In Burkina Faso, the SWEDD suspended its communication campaigns at the outset of the pandemic and later shifted them from in-person interactions to radio and TV presentations. The project also provided more remote support to partners and beneficiaries to overcome lockdowns. This approach, however, did not work for the poorest populations living in remote areas, who did not have easy access to phones or the internet. This was especially true of women and girls, who had the lowest access to means of communication as shown by national statistics.21 Similarly, Lebanon’s Women Entrepreneurs Finance Initiative project shifted from face-to-face to online training. A TTL for a project in Chad described the drawbacks of remote training as follows: “Remote learning inhibits engagement. It is second-best. Vulnerable people are the ones who have the least access.” The World Bank’s COVID-19 response project mitigated some of the pandemic’s impacts on the SWEDD by expanding social protection services, supporting girls’ and boys’ retention in school, and promoting GBV risk management in health services.

The World Bank supported FCV countries’ capacity to respond to COVID-19 but paid limited attention to alleviating growing gender inequalities. According to IEG’s evaluation of the early response to COVID-19, the World Bank financed an estimated $30 billion in health and social responses to COVID-19 in the first 15 months of the pandemic, with an emphasis on small states, less prepared countries, and fragile and conflict situations. This support addressed most emergency needs in a country’s COVID-19 response plans but paid little attention to protecting against long-term human capital losses. The Bank Group’s emergency response also paid insufficient attention to gender equality and women’s and girls’ protection. Over 60 percent of all projects addressing gender equalities were concentrated in just 21 percent of the FCV countries supported by the Bank Group, with about half of the FCV countries having no Bank Group project addressing those inequalities. Moreover, the emergency needs and the limited preparedness of health systems made it challenging for the Social Protection and Jobs Global Practice to follow the guidance provided by the Gender Group to address gender-related needs and inequalities during the pandemic’s early response (World Bank 2022h).

Box 4.3. Lebanon: When Multiple Contextual Factors Cause Crises in a Middle-Income Country

In fragility, conflict, and violence situations, sometimes multiple crises occur at once. This is what happened in Lebanon in 2020, when the COVID-19 pandemic, Beirut’s port explosion, and a massive financial crisis all hit the country at the same time. These compounded Lebanon’s long-standing postconflict issues, persistent gender role challenges, and capacity limitations. All these factors undermined the success of International Finance Corporation support to Al Majmoua to increase women’s access to credit. Before the crises, thousands of women-led small and micro enterprises were receiving credit from Al Majmoua, a nonprofit microfinance institution supported by the International Finance Corporation, but after the crises, many of these enterprises were suddenly unable to repay their loans. The financial crisis also evaporated Al Majmoua’s liquidity; thus, it could not provide additional loans. In response, the International Finance Corporation did not declare Al Majmoua in default but provided technical assistance to help it develop a crisis management plan. The crisis also undermined the Women Entrepreneurs Finance Initiative, a regional World Bank initiative supported by the World Bank and other donors. This financial issue, along with the destruction of property from the explosion, caused many beneficiary businesses to close. Moreover, the Women Entrepreneurs Finance Initiative beneficiaries were unable to register on international e-commerce platforms to sell their products because they could no longer afford the subscription fees caused by the unfavorable (and falling) exchange rate. In response, the World Bank provided technical assistance to help businesses advertise their products on social media and connect to local markets. The implementing partner (the International Trade Centre) established a partnership with the postal service to encourage internal commerce and payment of cash on delivery.

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Implementing Partners’ Awareness and Capacity

The awareness and capacity of implementing partners to address gender inequalities in FCV countries vary across countries and projects but are generally low. Key informants highlighted that the implementing partners’ limited awareness of gender issues constrained both project design and implementation. The gender focal point of a project implementation unit, for example, said: “When we talk about gender, people tend to say, ‘That’s women!’; however, gender is not just about women. There is still work to be done at the institutional level to better equip actors with knowledge of the true meaning of gender.”22 Several interviewees made it clear that implementing partners’ awareness is limited by their own embeddedness in local gender norms. A World Bank informant stated: “The difficulty is that the different actors are not open to bringing the risks of GBV into the discussion. GBV is taboo; people do not want to talk about it. They do not want agriculture or transport to deal with GBV, although something is starting to change with training and awareness raising.”23 In addition to the lack of gender awareness, the evaluation also identified two capacity gaps among implementing partners. These include their weak gender knowledge and skills (that is, a weak understanding of gender issues and how to address them in the specific intervention and context) and their low capacity to implement the innovative approaches to WGEE and GBV planned in project designs.

The World Bank addressed partners’ insufficient command of innovative project approaches by providing additional assistance and capacity building. For example, in Chad, the SWEDD’s implementing partners had difficulties implementing the theory of change, especially setting up and managing safe spaces for girls’ skill development, an innovation in Chad, and clubs for men and boys. This prompted the SWEDD to develop a comprehensive strategy to strengthen the capacities of local partners, through face-to-face training, technical assistance, regional workshops, and tours to other countries to learn through shared knowledge and experiences. In addition, the World Bank recruited two experienced INGOs to provide technical assistance to implementing partners in the SWEDD’s target countries.

- The gender strategy Mid-Term Review notes that “absent appropriate prioritization of gender in the program, a diverse set of projects tagged and flagged for gender in the portfolio can appear to be ‘sprinkled’ rather than strategic” (World Bank 2021f, 23).

- In French: « Ce sont les organisations comme la Banque Mondiale qui peuvent influencer le gouvernement, car ils donnent les prêts. Ils peuvent pressioner pour l’application des lois et pour la budgétisation sensible au genre. »

- These are low-income women belonging to the informal sector (supported by increasing their registration in credit bureaus), women pastoralists (supported by increasing their access to small ruminants’ vaccination services), and female heads of household (supported by increasing their proportion in the unified social registry of beneficiaries from social safety nets).

- In the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, the World Bank Group indirectly participates in gender and GBV coordination groups through the government implementing partners (the Social Fund of the Democratic Republic of Congo).

- In French: « La Banque devrait travailler avec les autres partenaires. Personne ne sait ce qu’ils font. Ils ne devraient pas rester isolés. . . . La Banque est un partenaire multilatéral et, de plus, elle a une expertise sur les questions économiques : elle pourrait orienter les autres partenaires, par exemple, sur un appui efficace pour l’autonomisation économique des femmes. »

- Most key informants from women’s rights organizations reported that the insufficient dialogue and collaboration with the Bank Group diminished the relevance, impact, and local ownership of Bank Group interventions.

- In French: « Un plaidoyer à l’endroit des chefs religieux ne suffit pas, il faut accompagner les leaders religieux. . . . Nous avons élaboré un document sur la base des textes de la religion et tradition africaines, nous avons des formateurs qui font le renforcement des capacités (des leaders) pour montrer que les préceptes religieux ne sont pas en contre le planning familial et sont contre les violence basées sur le genre. A partir de ce moment, ils s’engagent et ils portent ce message dans les mosquées, les églises et les courtes royales. »

- In French: « Les échanges avec les leaders religieux du Maroc ont permis aux leaders religieux du Tchad de comprendre que l’interprétation de l’Islam peut être flexible. »

- In French: « Il faut un travail sur les hommes pour un changement de mentalités, qu’ils soutiennent les femmes et ils ne fuient pas leurs responsabilités. »

- In French: « C’est plus facile pour les hommes de convaincre les hommes à laisser les femmes faire les choses. »

- The Project Appraisal Document states that “men and boys in targeted health zones will also benefit from project activities as survivors of [GBV], as family members of survivors and as key opinion leaders and community members promoting behavior change through [GBV] prevention programs” (World Bank 2018e, 16).

- The only contextual factor that significantly influenced the design of the specific set of projects analyzed in this evaluation was the political engagement of the counterpart, which was an enabler for most projects with the highest potential of transformational change (figure 4.2).

- In French: « L’insécurité limite l’expression et le regroupement pour passer les messages. . . . Certains thèmes exposent les travailleurs à des risques de représailles de la part des GANI [groupes armés non identifiés]. . . . Pour atténuer l’exposition des agents et des communautés aux GANI, les messages sont atténués. »

- In French: « Il y a eu aussi des villages où les terroristes étaient une menace, ils disent que ce que nous faisons dans les espaces surs est contraire à leurs prêches, donc il faut adapter les stratégies. Il ne faut pas faire beaucoup de bruits sur l’intervention. Ici nous avons demandé aux mentors dans les villages d’évaluer la menace. . . . Si la menace est relevée, il faut suspendre les activités pour ne pas mettre en risque les filles. Il y en a qui ne font plus l’animation dans des espaces fixes, elles font les animations dans la cour des familles, pour être confuses parmi les populations, ça n’attire pas l’attention. »

- Gender norms affected the presence of women and girls but also the quality of their participation. In many contexts, women and girls are not accustomed to speaking out during public events or in the presence of a man, leader, or elderly woman.

- In French: « Les normes sociales, elles sont à l’origine de tout. Par exemple (à cause des normes sociales), ce n’est pas facile (pour les survivants) dénoncer les cas des VBG, et même pour l’autonomisation des femmes, l’accès des femmes aux ressources et aux instances de décisions ça pose un problème à cause des normes. Dans certaines zones, les normes sociales empêchent la femme de s’exprimer. »

- In the Great Lakes Project, survivors of GBV faced major barriers to care seeking, particularly within 72 hours of sexual violence. These barriers included social acceptance of GBV and fear of stigma and isolation from survivors’ communities; inadequate penal systems to hold Independent Evaluation Group World Bank Group 97 perpetrators accountable; fear of retaliation from the perpetrator; lack of economic autonomy (and fear of losing the only source of income if the perpetrator is arrested); long distance to travel to access the service; GBV survivors’ lack of awareness of their rights and of available services; and preference for an “amicable solution” to avoid conflicts within the family or community (World Bank 2020h).

- In French: « Il y a aussi la sensibilité de sujets comme le mariage des filles. Dans certains contextes, comme le Sahel, on ne peut pas traiter le sujet de façon directe. »

- In French: « (SWEDD) répond aux besoins réels de la population, les bénéficiaires sont directement concernés par la mise en oeuvre. Le soutien arrive directement à la population. »

- People identifying as lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, intersex, and queer (and all the other gender and sexual orientations), or LGBTIQ+, reported concerns and fears of harassment and violence from increased security patrols and checkpoints enforcing the lockdown. Because of deteriorating economic conditions, LGBTIQ+ individuals have reported moving back in with abusive and homophobic or transphobic family members or partners, increasing their exposure to violence.

- In 2015, among 100 adults who reported owning a smartphone in Burkina Faso, 67 percent were men and 33 percent were women (Karlsson et al. 2017).

- In French: « Quand on parle du genre les gens ont la tendance à dire: ‘C’est les femmes!’, mais le genre ce n’est pas que les femmes. . . . Il y a encore du travail à faire au niveau institutionnel pour mieux outiller les acteurs sur le vrai sens du genre. »

- In French: « La difficulté est que les différents acteurs ne sont pas ouverts à mettre les risques de violences basées sur le genre (VBG) dans la discussion. Les gens ne veulent pas que on en parle. Elles ne veulent pas que l’agriculture ou le transport s’occupent des VBG, mais ça commence à changer avec la formation et la sensibilisation... Les VBG sont un tabou, les gens ne veulent pas en parler. »