The World Bank Group's Engagement in Morocco 2011-21

Chapter 3 | Leveling the Economic Playing Field

Highlights

Morocco has an economy where micro, small, and medium enterprises do not compete on a level playing field with large established firms and state-owned enterprises.

The World Bank Group capitalized on Morocco’s desire to improve its Doing Business ranking by promoting wider reforms for fair market competition in Morocco.

The Bank Group strengthened domestic organizations that promote fair competition and ease of doing business for micro, small, and medium enterprises.

The Bank Group’s efforts to increase competitive neutrality between state-owned enterprises and private businesses were piecemeal and disparate, ultimately yielding limited results.

The Bank Group’s limited involvement in Morocco’s industrial policy constrained its ability to improve the country’s business environment.

The Bank Group helped micro, small, and medium enterprises and poor households access finance through a comprehensive approach to reform financial systems, the capital market, microfinance institutions, and the commercial banking sector.

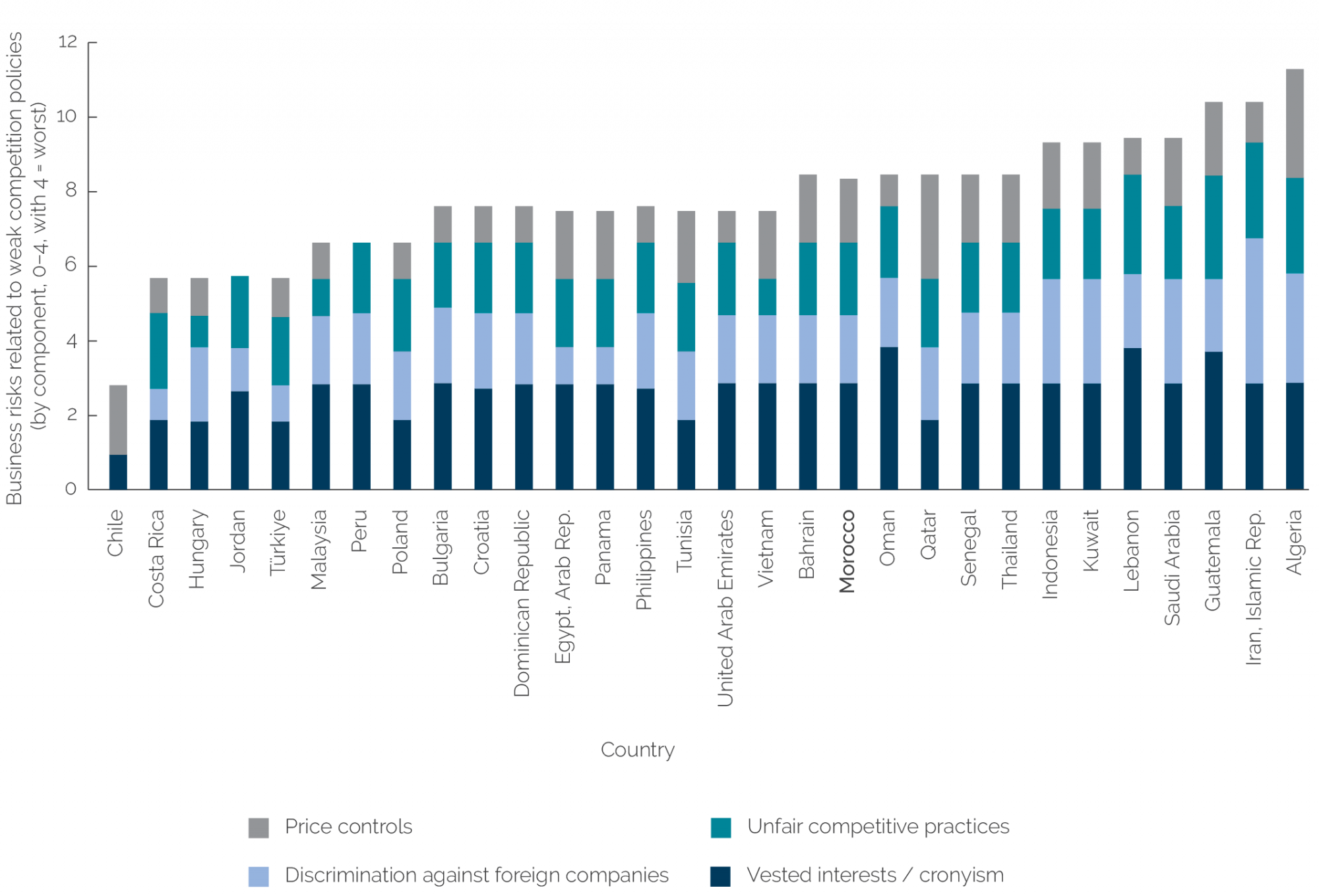

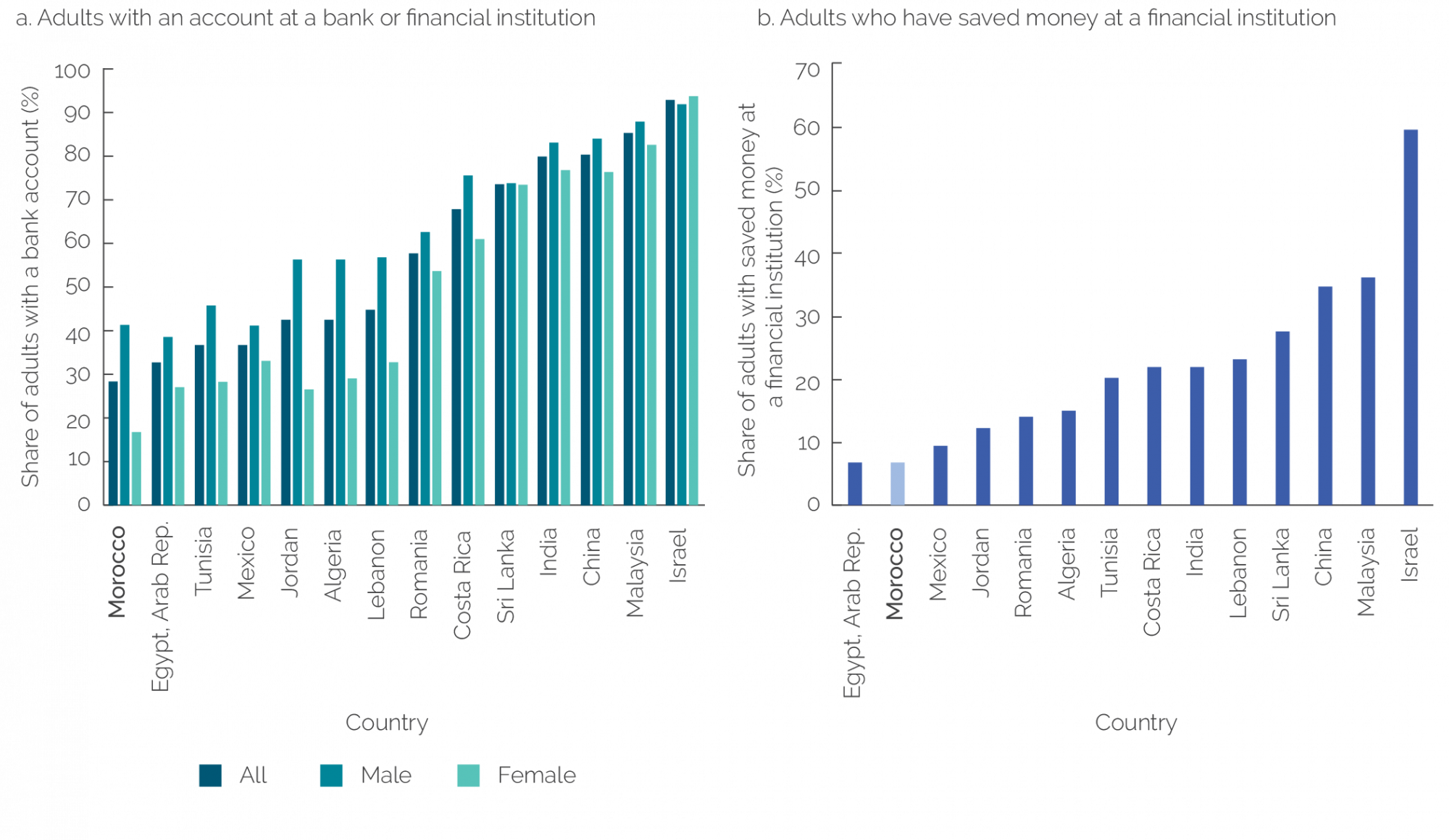

This chapter evaluates the Bank Group’s efforts to level Morocco’s economic playing field and develop the country’s private sector. In Morocco, large established firms and SOEs do not compete on a level playing field with SMEs and small private businesses. According to the NDM,1 this is Morocco’s second systemic obstacle to development (CSMD 2021). Morocco’s anti-monopoly policy and market-based competition remain weak compared with other Middle East and North Africa countries (figure 3.1). Moroccan SOEs play a key role in Morocco’s development, but they discourage private investment and increase fiscal pressure on the state. Morocco is among only 10 countries where SOEs are present in most national economic sectors (23 sectors).2 Consequently, state-guaranteed concessional debt to SOEs amounts to 15 percent of national GDP. In addition, Morocco’s industrial policy provides incentives and tax breaks to SOEs and preferred foreign and domestic investors, creating an uneven playing field for other small domestic firms (IFC 2019). Believing that limited competition and an overrepresentation of SOEs are major obstacles to economic development, the NDM calls for strengthening anti-monopoly policy and increasing incentives for SMEs and small private businesses. This chapter covers IFC and World Bank efforts to overcome this systemic obstacle. These efforts build on important Bank Group contributions in the 2000s to enhance competition in key sectors, such as telecommunications. Across the three strategy periods covered by the evaluation, the Bank Group focused on improving the business environment and enhancing access to finance, particularly for MSMEs. This analysis shows that the Bank Group achieved notable success in pursuing both goals, but its efforts to reform SOEs and enable private sector participation did not go far enough.

Figure 3.1. Select Competition Indicators for Morocco and Comparator Countries

Sources: International Finance Corporation 2019; Transformation Index BTI 2018 (https://bti-project.org/en/?&cb=00000).

Increasing Competition

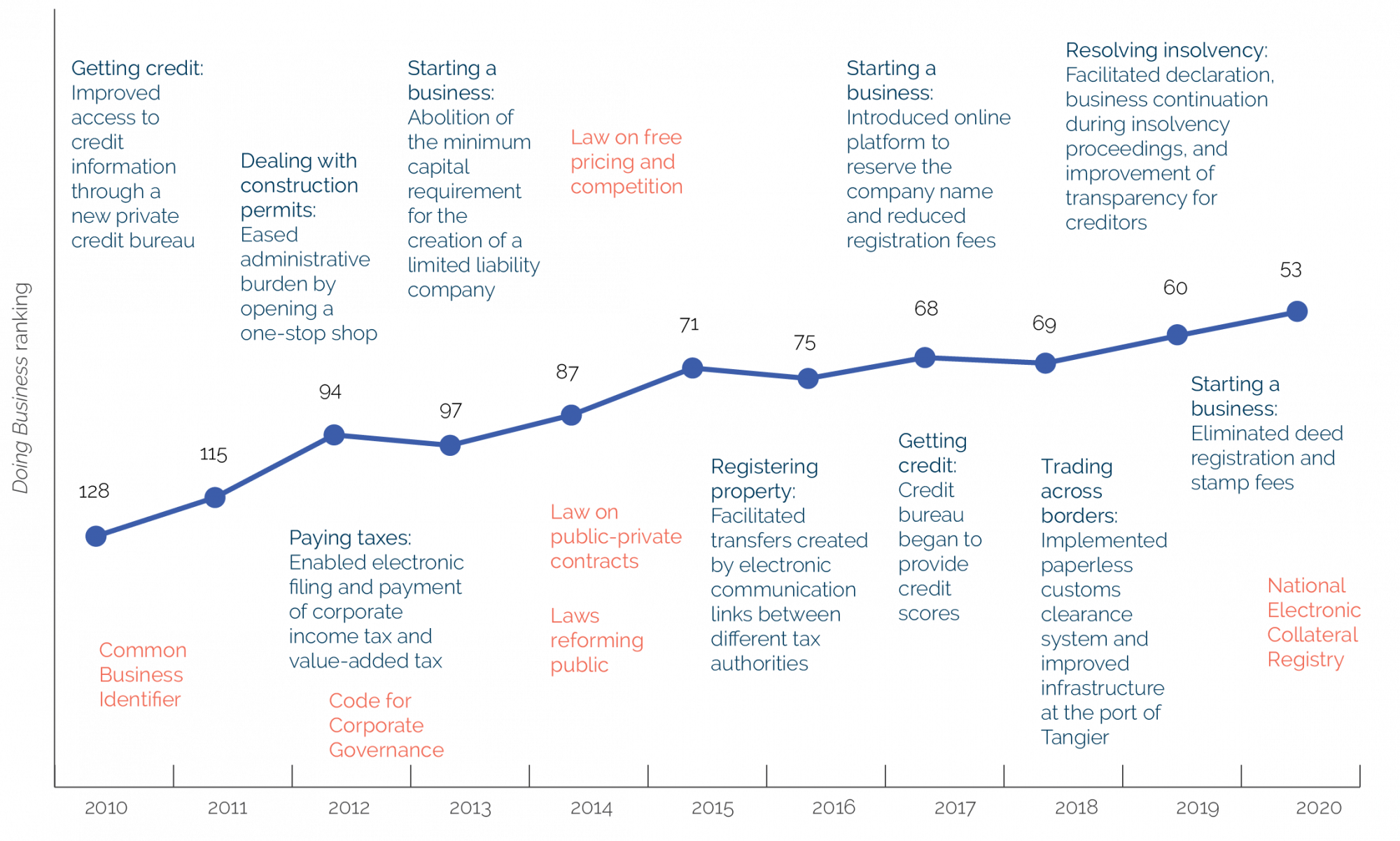

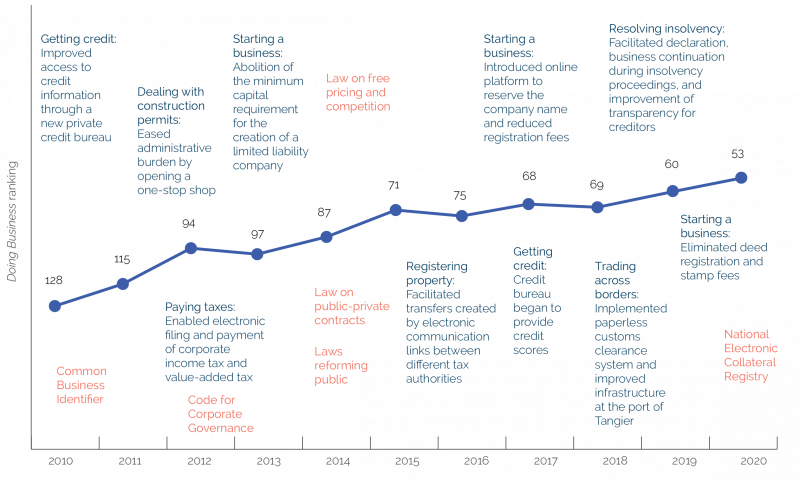

The Bank Group capitalized on the Moroccan government’s desire to improve its DB ranking to achieve wider business climate reforms. The 2022 Independent Evaluation Group evaluation of the World Bank’s DB indicators recognizes the powerful motivational effect they can have for governments (World Bank 2022a). In 2010, Morocco ranked 128th among 180 countries in the DB rankings. In interviews, government officials said that the low DB ranking catalyzed action at the government’s highest levels to achieve progress.3 In response, during the FY10–13 strategy period, IFC and the World Bank formed a DB advisory team to improve Morocco’s performance in the 10 areas of business regulations.4 This team helped Morocco improve its DB ranking to 53rd place in 2020 (figure 3.2). However, IFC and the World Bank did not stop there; they seized the opportunity to address other constraints not measured by DB indicators. Drawing on the findings of Enterprise Surveys for Morocco, the World Bank identified and helped the authorities to address other constraints to private sector growth not covered by DB indicators, such as limited labor skills, insufficient access to land and finance, and low institutional capacity. For example, the World Bank’s programmatic DPO series—the Economic Competitiveness Support Program, which totaled $360 million between 2013 and 2015—included prior actions to reduce payment delays, regulate competition, and bring more transparency when awarding government contracts. The Bank Group also worked with the National Committee for Business Environment (Comité National de l’Environnement des Affaires; CNEA) to facilitate intergovernmental communication, increase access to enterprise data, and increase the transparency and efficiency of business registration, tax administration, customs procedures, and other public services to private firms. Moreover, the World Bank supported the introduction of the Common Business Identifier to improve the interoperability of government agencies and reduce the number of required documents and administrative transactions for creating and expanding businesses. It also enabled government systems to track enterprise data across tax, commercial, and social security registries. This work helped the government—through the Moroccan SME Observatory—better understand the constraints to enterprise development in Morocco and propose additional solutions. In 2021, the Bank Group discontinued the DB report and is currently developing a more comprehensive approach for assessing business and investment climates.

The Bank Group’s efforts to level the economic playing field were boosted by helping the CNEA champion fair business practices. With Bank Group support, Morocco’s government created the CNEA. Chaired by the prime minister, the CNEA is well positioned to mobilize technical leads across government agencies to change regulations. IFC notably provided technical assistance to build the CNEA’s capacity to develop an action plan, coordinate investment climate reforms, and develop a monitoring and evaluation (M&E) framework, among other efforts. In 2019, IFC supported the CNEA’s Enterprise Survey and COVID-19 follow-up surveys, which informed the government’s 2021–25 business environment strategy. As a result of these efforts, the CNEA became the main agency driving the improvement in Morocco’s business climate.

Figure 3.2. Morocco’s Improvement in the Doing Business Ranking, 2010–20

Source: Independent Evaluation Group, using the World Bank’s Doing Business database.

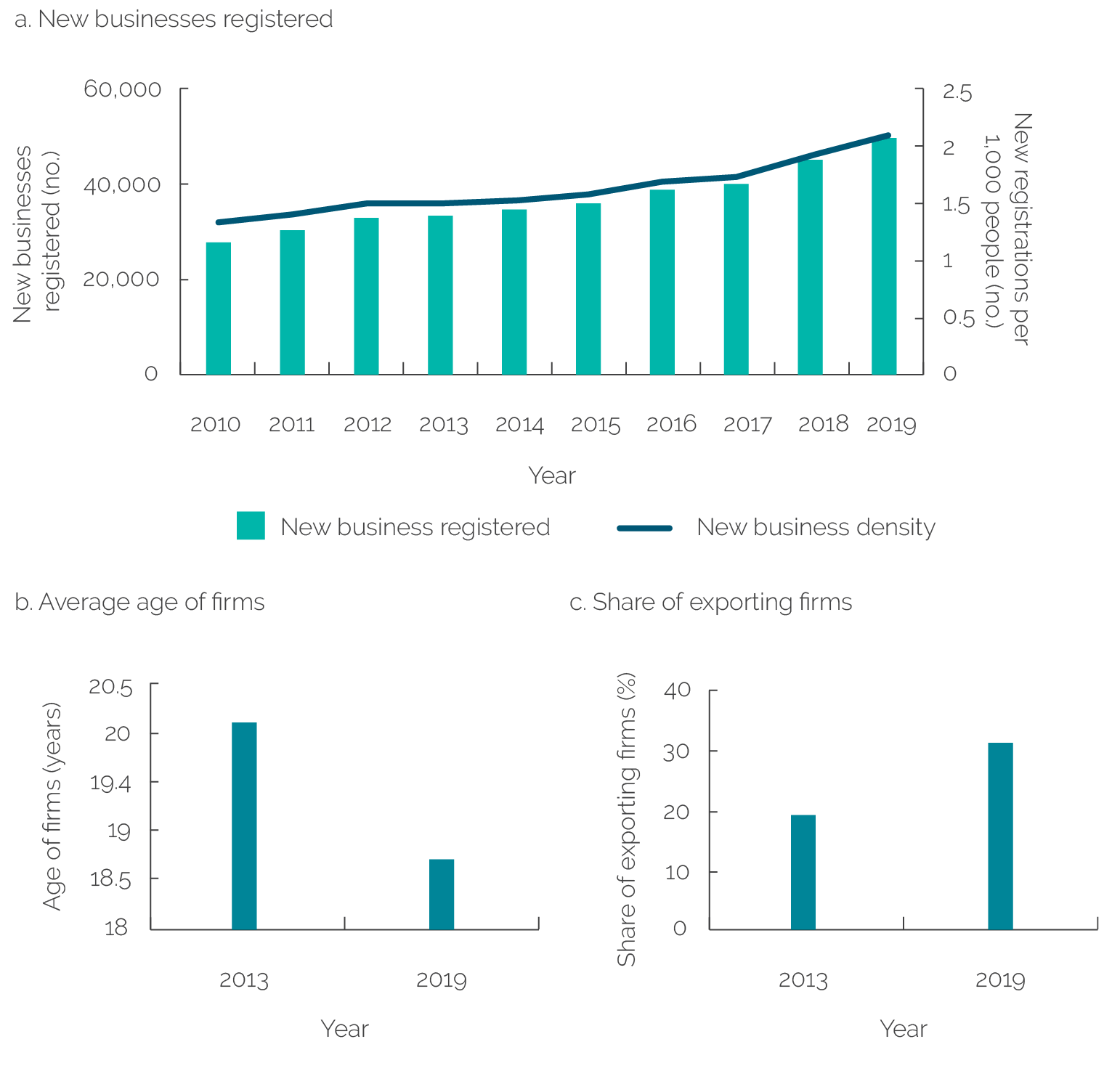

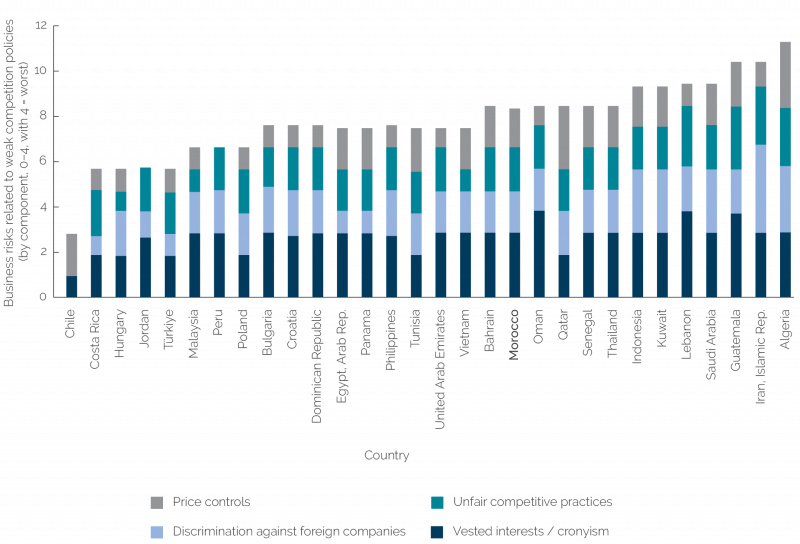

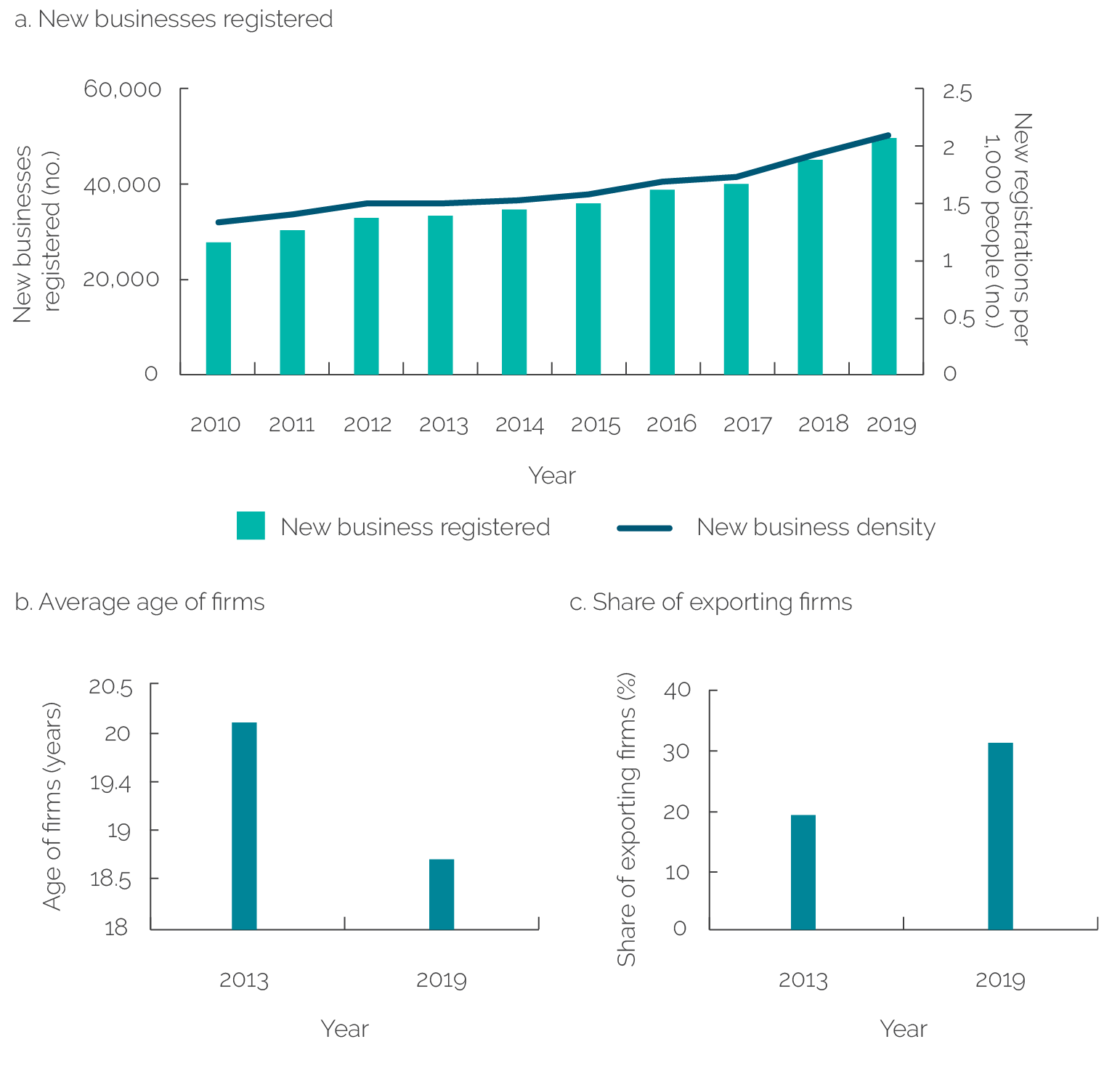

The Bank Group’s efforts to help Morocco improve its Competition Council led to long-awaited legal and institutional reforms. A key objective of the Economic Competitiveness Support Program development policy loan (DPL) series was to transition the Competition Council from an advisory body to an independent regulatory agency with the power to investigate and sanction monopolistic behavior and private sector collusion. Supported by the Economic Competitiveness Support Program prior actions, Moroccan authorities passed two laws in 2014 that strengthened the powers of Morocco’s Competition Council. Both the Bank Group and the EU, through a twinning agreement between the Moroccan and German Competition Councils, provided inputs on the reforms. The reforms created laws to regulate competition and equip the Council’s permanent staff with knowledge and resources.5 IFC built the council’s capacity in antitrust investigations and market intelligence operations. IFC also helped the Council and the Ministry of Finance develop guidelines and criteria to assess mergers and partnered with Morocco’s largest business association to train firms and the media on how to use the Competition Council.6 As a result of these efforts, the “reactivated” Competition Council exercised its new powers to investigate and issue official decisions, of which there were 106 in 2019 and 82 in 2020 (Government of Morocco 2019b, 2020). Low competition remains a business risk in Morocco (figure 3.3), but these reforms increased the dynamism of the private sector. For example, the number of new businesses registered steadily increased from 2010 to 2019 (figure 3.4, panel a) and the average age of firms decreased, suggesting that older established firms exited the market while newcomers entered (figure 3.4, panel b). The share of enterprises that export products also increased from 19 percent in 2013 to 31 percent in 2019, which was well above the Middle East and North Africa average (22 percent; figure 3.4, panel c).

IFC helped the government establish alternative dispute resolution (ADR) mechanisms to overcome high fees and long delays in commercial courts. These costs and delays stemmed from ineffective case management, transparency, and anti-corruption mechanisms (IFC 2019). Through a series of advisory projects, IFC helped Morocco draft and roll out an ADR strategy, train mediators, launch mediation courses through business schools, develop an ADR center in Casablanca, and draft a new law on court-connected mediation. The ADR mechanism referred over 2,000 cases to mediation with 80 percent of these disputes being resolved. These cases mainly benefited SMEs, not SOEs, and resulted in about $236 million being released back to the private sector for productive uses. Moreover, private sector clients saved an estimated $198 million by not using the commercial courts to resolve disputes. The ADR mechanism helped reduce the courts’ backlog of cases, particularly those related to SMEs in the banking and insurance sectors. The ADR mechanism contributed to improving Morocco’s global DB ranking in contract enforcement from 108 in 2010 to 60 in 2020.

The World Bank helped improve transparency and accountability in public procurement by focusing on strengthening a few key institutions. Government contracts represent 17 percent of Morocco’s GDP but are tilted toward privileged firms and SOEs. The World Bank’s Country Procurement Assessment Reports during the 2000s highlighted shortcomings in the national procurement system, including the lack of a credible and independent complaint-handling system, the exemption of certain contracts from public procurement regulations, and the fact that public procurement decrees did not apply to nonstate entities. The World Bank used its Transparency and Accountability DPO series (Hakama; $407 million during 2013–16) to enforce public procurement decrees (World Bank 2020a). These laws bring SOEs within the public procurement regulatory framework, introduce electronic procurement, open construction contracts to competition, and mandate that 20 percent of public contracts are allocated to SMEs. To achieve these legal changes, the World Bank created or built the capacity of institutions involved in public procurement. For example, in 2016, with the support of a World Bank–financed Institutional Development Fund operation, Morocco established the National Commission for Public Procurement as an independent body to handle grievances. The World Bank also trained key partners in SOEs, the Treasury, the CNEA, relevant ministries, and Regional Investment Centers (Centres Régionaux d’Investissement; CRIs) in e-procurement. These efforts helped SMEs access public procurement markets and improved the procurement process for public-private partnerships (PPPs). However, those efforts need to be further strengthened to ensure efficient management of government contracts. The share of domestic firms that gave gifts to secure government contracts barely moved from 60 percent in 2013 to 58 percent in 2019, which is far above the average of 32 percent in Middle East and North Africa and lower-middle-income countries (World Bank Enterprise Surveys, 2013 and 2019).

Figure 3.3. Business Risks Related to Weak Competition Policies in Morocco and Other Comparators

Sources: Economist Intelligence Unit 2018; International Finance Corporation 2019.

Figure 3.4. The Dynamism of Morocco’s Private Sector

Sources: ILOSTAT database, International Labour Organization; World Bank Enterprise Surveys (2013 and 2019) based on the year the firm began operations.

Note: Panel b is derived from a sample of n = 392 (2013) and n = 1,001 (2019) firms, compared with the Middle East and North Africa average of 22.2 years (no year provided). Panel c uses World Bank Enterprise Surveys based on the year the firm began operations. Derived from a sample of n = 393 (2013) and n = 973 (2019) firms, compared with the Middle East and North Africa average of 21.6 percent (no year provided).

However, the Bank Group’s efforts to support the achievement of economywide impacts through SOE reform were not successful. SOEs received 55 percent of public investments between 2008 and 2015 (IFC 2019), but about 40 percent of SOEs operate at a loss. As a result, public subsidies to SOEs were about 2 percent of GDP, and earmarked revenues (in the form of tax advantages) to SOEs were 0.4 percent of GDP. The World Bank’s Hakama DPO series was the World Bank’s main operational engagement on SOE reform. The series included prior actions to increase the government’s financial oversight of SOEs, adopt the Code for Corporate Governance, bring SOE governance structures in line with international standards, and increase SOE transparency. The DPF also supported SOEs to publish the names of their boards of directors and provide up-to-date financial statements, although this information was often incomplete or not comprehensive (World Bank 2020a). Meanwhile, IFC developed a director-certification program for SOE boards and trained SOEs on corporate governance, ultimately leading to revisions of the Code for Corporate Governance. However, more effort is needed to significantly reduce the tax burden of public enterprises, thus overcoming distortions related to the overrepresentation of public enterprises in the Moroccan economy.

IFC’s efforts to reduce payment delays from large firms and SOEs to MSMEs showed limited progress. Between December 2013 and January 2017, IFC and the CNEA implemented the Morocco Public Service Delivery and Transparency project to improve the transparency of public procurement and reduce public payment delays. The project motivated the government to issue an official decree in 2016 that caps public payment delays at 60 days and penalizes public entities if they exceed the cap. The project also developed indicators to monitor payment delays and piloted the use of these indicators in seven municipalities. However, the low capacity of municipal-level clients hindered their ability to continue using the indicators after the project closed. As a result, at project completion, only one of the seven municipalities fully adopted the indicators and used them to improve payment practices. In 2020, IFC launched a project with the CRI to improve local capacity and reduce public payment delays at the subnational level, specifically for firms operating in the Marrakech-Safi region. In 2021, IFC initiated a supply chain finance pilot program with the country’s largest bank to help SMEs stay afloat during long payment delays. It is too early to know the effects of IFC’s latest efforts, but a recent survey of 385 companies shows that payment delays remain widespread, with nearly half of respondents saying that they experienced delays longer than three months (Ametan and Fruchter 2022). Figure 3.5 shows that these delays disproportionately affect smaller companies.

Figure 3.5. Unpaid Invoices as a Percentage of a Company’s Turnover

Source: Ametan and Fruchter 2022.

Note: Based on a survey of 385 companies located in Morocco that was carried out in 2021 by Coface Business Research Unit. SME = small and medium enterprise.

The Bank Group has had limited success promoting PPPs, and most of IFC’s planned PPP investments and advisory projects did not materialize. The Bank Group’s three country strategies during the evaluation period all advocated using PPPs to invigorate the country’s private sector and enhance the competitiveness of public services. However, the country’s regulatory and institutional framework for PPPs remains inadequate. The central PPP unit, which the government created in 2011 with support from a World Bank DPF operation, is still not fully operational and has limited capacity to create PPPs or monitor and evaluate PPP performance. The 2015 PPP law, supported by the second DPF operation of the Hakama series, had a limited scope. The law mandated assessments of PPPs’ financial viability and the publication of PPP contracts, but it included many built-in exceptions. During the evaluation period, none of IFC’s PPP advisory projects materialized, with seven concrete attempts not progressing beyond the Concept Note stage. IFC also withdrew from a desalination and irrigation PPP in the Chtouka region—one of the largest agriculture areas in the country—after a detailed feasibility study showed that the project’s location in a natural reserve would lead to biodiversity and displacement issues and that the project would require unsustainable government subsidies and ongoing operational expenditures.

While the Bank Group has supported pioneering solutions on renewable energy, it had little impact on improving market and regulatory conditions to enable the competitive distribution of electricity from smaller-scale renewable energy sources. The Bank Group and other key partners (such as KfW Development Bank, the European Investment Bank, and the African Development Bank) have helped Morocco make significant investments in developing Morocco’s renewables as further laid out in chapter 4. However, those efforts were state led, and so far, partners have not made much progress in helping the state shift its role from primary investor to catalyst of private investments. Despite efforts to liberalize the electricity sector since the mid-1990s, the sector is still vertically integrated by the state-owned operator—the National Office for Electricity and Drinking Water (l’Office National de l’Electricité et de l’Eau Potable)—and dominated by influential holdings with vested interests. Although the private sector is active in electricity generation, the National Office for Electricity and Drinking Water remains the single buyer of electricity from producers, and a wholesale market has yet to be developed. According to the Global Power Sector Reform Index, Morocco is ranked 55 out of 88 on four dimensions of reform (regulation, competition, private sector participation, and restructuring). When compared with its middle-income peers, such as Türkiye, Argentina, or Mexico, Morocco’s performance in enhancing competition is rather weak. In this context, the Bank Group made little headway in improving competition and unlocking the renewable energy sector to small-scale actors. For example, the Inclusive Green Growth DPO series’ prior actions included decrees that would open low- and medium-voltage distribution networks to individual, commercial, or industrial investors. However, it did not include decrees defining the amounts of green capacity to be added yearly at the regional level. These decrees have yet to be approved by the government.

Enhancing Access to Finance

The World Bank and IFC complemented one another’s work to promote inclusiveness in Morocco’s microfinance industry. During the 2008 financial crisis, one large Moroccan microfinance institution (MFI) failed, and several others teetered on the verge of failing, potentially affecting over 1.2 million MFI customers. In response, the World Bank supported major reforms to MFI governance and oversight. An Independent Evaluation Group review found that the reforms led to better risk management within MFIs. As a next step, IFC provided joint investment-advisory services to help the three largest MFIs (which cover 95 percent of the microfinance market) decrease their number of nonperforming loans (which had risen from 1 to 10 percent during the crisis). Next, IFC helped the three MFIs improve their risk management and corporate governance practices to better cope with economic downturns and develop new products for very small enterprises. IFC then built the financial management capacity of the three MFIs so they could transform from nongovernmental organizations to nonbank financial institutions (NBFIs), which would allow them to expand their product offerings and financing capacities for MSMEs. However, none of the MFIs were able to transform into NBFIs because, although the Microfinance Law was passed in 2012 and amended in 2021, the decrees enabling the enactment of the law and the central bank’s licensing have not been approved. IFC noted that the delay was caused by resistance from the banking sector, which feared potential competition from NBFIs and more nonperforming loans from MFIs because of COVID-19. The World Bank’s 2021 Financial and Digital Inclusion DPF seeks to overcome these barriers by amending the law and strengthening enforcement measures.

The Bank Group helped Morocco upgrade its oversight framework for capital markets and developed new solutions for SMEs. The World Bank used technical assistance (the FIRST [Financial Sector Reform and Strengthening Initiative] program), the Sustainable Access to Finance DPL ($200 million), and the First and Second Capital Market Development and SME Finance DPLs (totaling $750 million) to develop oversight guidance and create the Moroccan Capital Markets Authority. Building on these achievements, in 2019, IFC and the World Bank started the Joint Capital Market Advisory Program to develop new markets for SMEs and mobilize long-term capital market financing. The Joint Capital Market Advisory Program enabled the Casablanca Stock Exchange to open and list an SME window for the first time, although this service remains underused. Together, these efforts have improved market liquidity, developed new asset classes, and improved the Casablanca Stock Exchange’s performance (Oxford Business Group 2019). However, challenges remain: the market capitalization of listed domestic companies still declined from 74 percent of GDP in 2010 to 57 percent of GDP in 2020,7 and the Casablanca Stock Exchange remains relatively illiquid because of the lack of domestic capital investments in listed companies. As a result, large firms continue to work with the traditional banking sector, where they have historically found ample liquidity, but this crowds out credits for SMEs.

Throughout the evaluation period, the Bank Group kept a clear focus on improving financial inclusion for rural and low-income communities. The Sustainable Access to Finance DPL helped financial institutions reach lower-income individuals and communities. For example, the DPL’s prior actions transformed the Moroccan Post, a savings provider for low-income households, into a full-fledged bank (Al Barid Bank [ABB]). With its new legal status, ABB began offering comprehensive financial services, including credit, mortgages, cash transfers, and mobile banking. The DPL prior actions also enlarged ABB’s branch network, especially in rural communities. Between 2009 and 2021, the number of ABB branches nearly doubled, with two-thirds of ABB outlets in rural areas—a greater rural presence than any other bank in Morocco. The FY10–13 CPS Completion Report Review noted that the proportion of the Moroccan rural population with bank accounts increased from 50 percent in December 2010 to 58 percent in June 2013 (World Bank 2014c). More broadly, this banking expansion into rural communities helped the government deliver social protection services. For example, many rural households—including three-quarters of a million children—collect benefits from Morocco’s conditional cash transfer program, Tayssir, through their local ABB branch. Moreover, during COVID-19 lockdowns in 2020, ABB customers received benefits from the government’s World Bank–supported emergency cash transfer program, Tadamon. Additionally, in 2014, the World Bank carried out a Financial Inclusion and Capability Survey and, in 2017, produced a Financial Inclusion Technical Note, both of which served as inputs into Morocco’s National Financial Inclusion Strategy (BAM 2018).8 The Technical Note, according to the International Monetary Fund, was “appropriately comprehensive, builds on international best practice, and is associated with clear objectives and specific action plans” (IMF 2019, 55). The 2020 Financial and Digital Inclusion DPF included prior actions to implement the National Financial Inclusion Strategy.

IFC leveraged its know-how and comparative advantage in financial infrastructure to deliver impactful operations in Morocco. IFC partnered with Morocco’s central bank, BAM, to revise its supervision framework for credit reporting and, in 2009, launched its first-ever private credit bureau in the Middle East and North Africa and Africa regions. This project had a demonstration effect, with BAM training other central banks on credit reporting supervision. IFC encouraged the accreditation of a second private credit bureau, which was launched in 2018. This introduced competition, incentivizing the two bureaus to improve data and service quality and lower costs for banks and MFIs, ultimately making credit more affordable. Meanwhile, IFC’s advisory services helped Morocco further improve its financial inclusion legislation by allowing credit bureaus to recognize nonfinancial resources as assets. This change enabled the large share of the population without a credit history to obtain a credit profile and access finance—by 2019, a third of female and a quarter of male borrowers were new to financing, according to credit reports. IFC then helped BAM launch the country’s first movable electronic collateral registry in early 2020. According to the Ministry of Justice, about 41 financial institutions participated in the collateral registry, and, as of December 2021, the registry has already exceeded the targets it had set for 2024. As a result of these efforts, the share of Moroccan adults with credit reports increased from 20 percent in 2013 to 32 percent in 2019. The higher-quality credit reports and better information for lenders helped decrease nonperforming loans from 6.1 percent in 2010 to 3.5 percent in 2019. IFC’s advisory services also helped Morocco’s two largest banks develop new lending products for very small enterprises and a new supply chain financing product to help MSMEs access credit and withstand payment delays from SOEs and large firms.

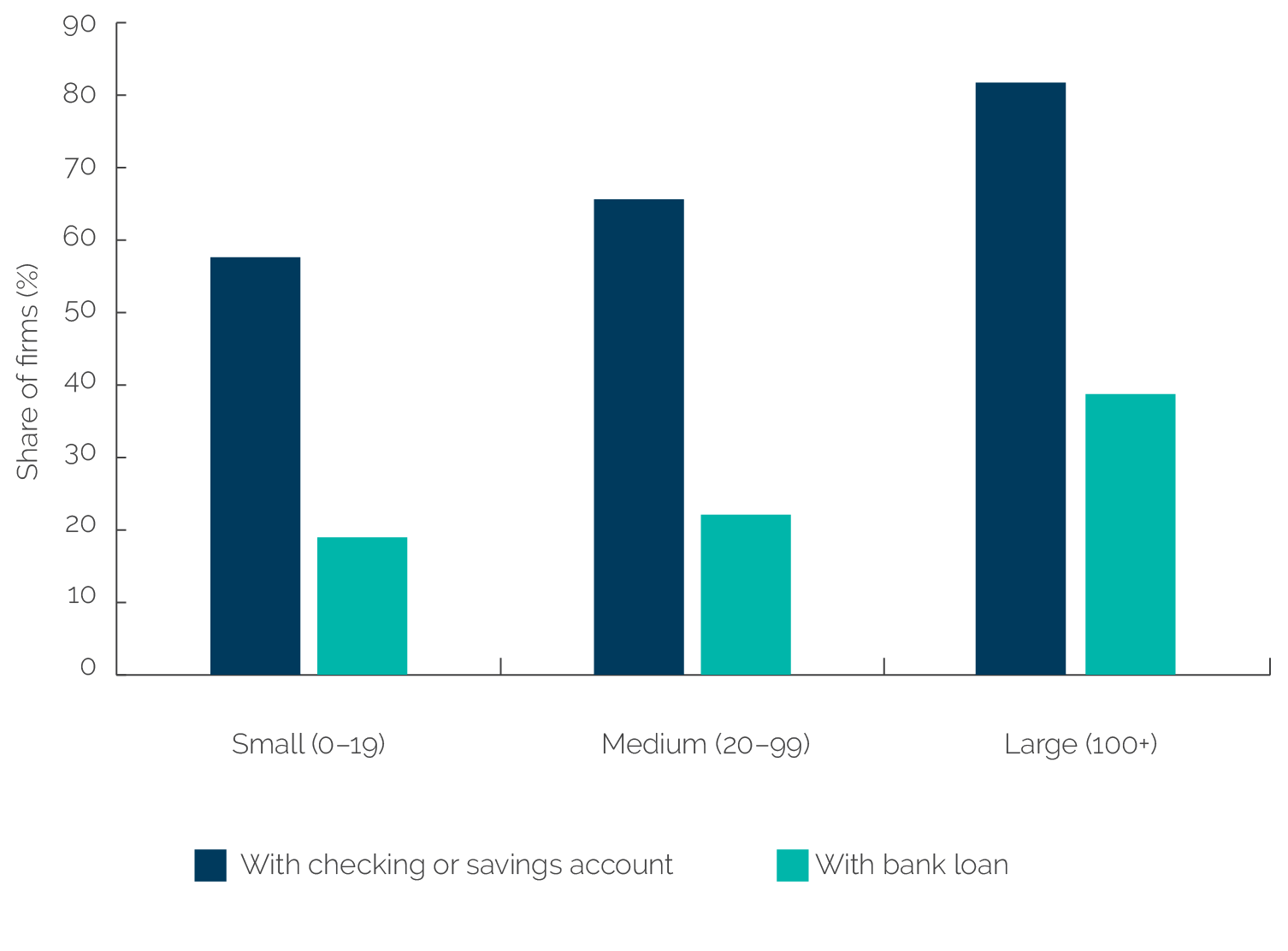

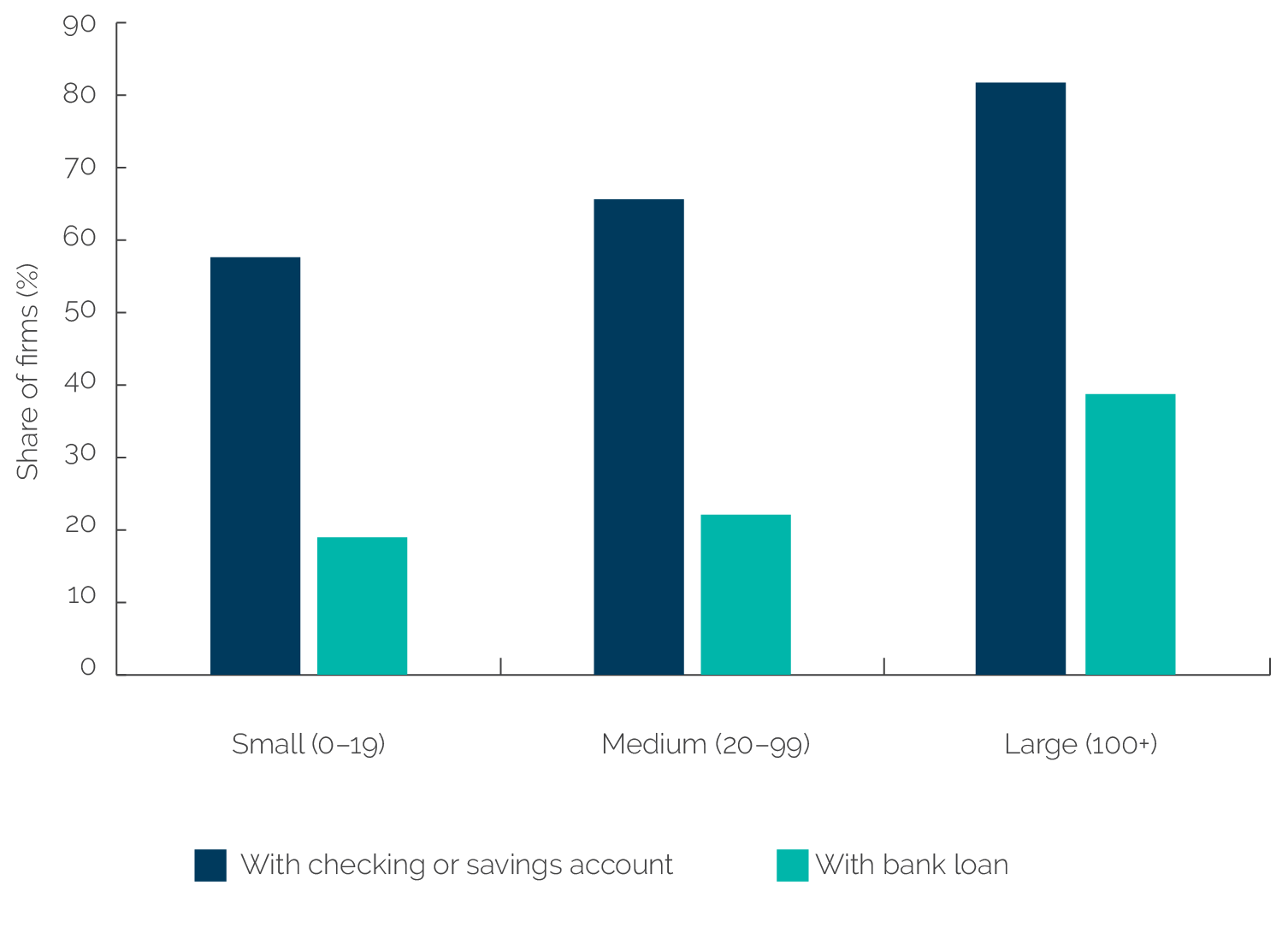

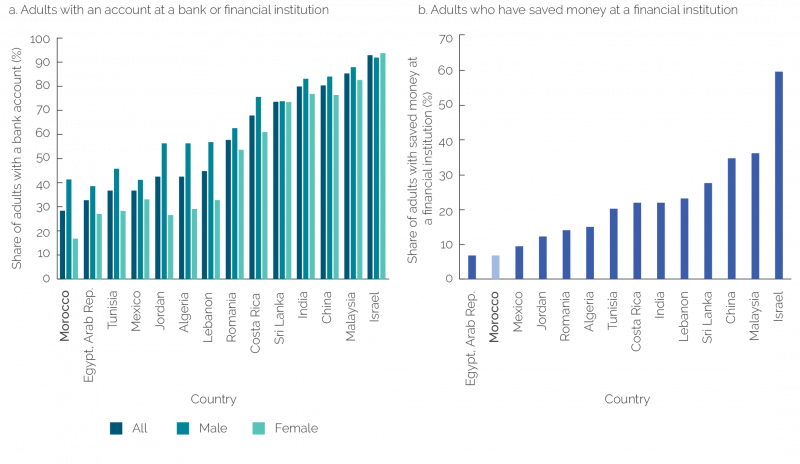

Despite the above efforts, access to finance continues to be a major constraint to doing business in Morocco. In 2019, only 19 percent of small firms had received bank loans—62 percent still rely on their own capital to finance investments (figure 3.6)—and the share of Moroccans with a bank account remains low compared with other countries (figure 3.7). State-supported loan guarantees and cofinancing have helped narrow these gaps, but Morocco’s big banks dominate the financial market and maintain relatively conservative lending practices. Moreover, 40 percent of large enterprises still rely on bank loans to meet their financing needs, possibly crowding out riskier small businesses from receiving loans. As discussed, MFIs have not yet transformed into NBFIs or expanded their lending and financial services. Additional Bank Group reforms to ease collateral requirements and strengthen bankruptcy laws, which reinforced the rights of both lenders and borrowers, came too late in the evaluation period to show much progress on accessing credit. That said, the World Bank’s 2019 Enterprise Survey shows progress, with 4 percent of firms reporting access to finance as the biggest constraint in 2019, compared with 32 percent reporting the same in 2010. Box 3.1 recaps the Bank Group’s contributions to private sector development.

Figure 3.6. The Use of Financial Services by Enterprise Size, 2019

Source: World Bank Enterprise Survey for Morocco 2019.

Figure 3.7. Financial Inclusion in Morocco and Comparator Countries

Source: Global Financial Inclusion (Global Findex) database 2017.

Note: For Morocco, Global Findex held face-to-face interviews in Moroccan Arabic, and an equal sample size was used for each region (disproportionate sampling), with data weighted to population distribution.

Box 3.1. Outcome: The World Bank Group’s Contributions to Private Sector Development

- The World Bank Group strengthened state institutions in charge of promoting competition and competitive neutrality. The Bank Group was an unwavering advocate and supporter of the government’s Competition Council, helping to empower the institution to investigate antitrust cases and make sanctioning decisions. The Bank Group also supported the leadership of the National Committee for Business Environment in easing business practices and strengthened public procurement mechanisms to make them more transparent and accessible to micro, small, and medium enterprises. The International Finance Corporation (IFC), for its part, contributed to rolling out an alternative dispute resolution mechanism to decrease the courts’ backlog in cases and arbitrary rulings.

- The Bank Group, in partnership with the National Committee for Business Environment, balanced policy financing and advisory services to improve Morocco’s business and regulatory environment. The Bank Group’s support contributed to simplifying the process for creating a corporation, improving corporate governance, and making corporate finances more transparent. It introduced a framework that clarified more than 50 of the procedures required to create and maintain a business. With Bank Group advisory support, Morocco also lowered the minimum capital requirement to zero for a limited liability company and streamlined the process for registering a business or property, obtaining a construction permit, and establishing an electricity connection. The World Bank also helped Morocco develop information systems—such as the Common Business Identifier and PortNet—to improve enterprise data availability and boost the efficiency and transparency of public services, customs procedures, business registration, and tax administration procedures.

- The Bank Group contributed to improving access to finance for micro, small, and medium enterprises and low-income households. IFC supported lending institutions to make access to credit more open and less arbitrary. IFC built the central bank’s capacity in credit supervision. It helped create two private credit bureaus, the first movable collateral registry, and alternative credit access mechanisms that accept credit applicants’ nonfinancial assets as collateral. These changes expanded the pool of Moroccans with access to finance: by 2019, about a third of female borrowers and a quarter of male borrowers were new to financing. The Bank Group also helped expand banking services to underserved localities, lower-income groups, and microenterprises. With World Bank support, the Moroccan Post (now Al Barid Bank) transformed into a full-fledged bank with new branches that offer comprehensive financial services to underresourced households. Moreover, these Al Barid Bank branches and new digital services distributed Tayssir and Tadamon cash transfer payments during COVID-19. The Bank Group also helped stabilize microfinance institutions and diversified their services to reach more microenterprises and microborrowers. With IFC’s support, Morocco’s three main microfinance institutions reduced their number of nonperforming loans, expanded their branch networks to remote areas, and developed specific products for very small enterprises.

- However, Bank Group efforts to support the achievement of economywide impacts through state-owned enterprise reform were not successful. Core diagnostics, such as the 2017 Country Economic Memorandum and the 2019 Country Private Sector Diagnostic, highlighted the need to enhance government efforts to address anticompetitive practices to reduce economic distortions. However, as discussed in chapter 2, the World Bank was unable to directly inform the industrial policy. Moreover, as discussed in chapter 3, the Bank Group’s efforts did not go far enough to alter state-owned enterprises’ fiscal burdens, distortionary advantages, or overrepresentation in the Moroccan economy.

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

- The New Development Model describes Morocco’s economy as “partially locked” because of government regulations that reinforce oligopolistic positions and anticompetitive practices, making it difficult for new businesses to access markets; limited actions against oligopolies; and public incentives that privilege state-owned enterprises or large corporations engaging in foreign direct investments (CSMD 2021).

- Across countries for which data are available in the Product Market Regulation (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development–World Bank database).

- Doing Business indicators covered the assumed key elements of a prototypical small and medium enterprise business life cycle, from start-up through operation to exit. They included 12 areas of business regulations (10 of which fed an overall ease of doing business index measuring the ability to “do business” in 190 countries; World Bank 2022a).

- Doing Business indicators included starting a business, employing workers, enforcing contracts, getting credit, resolving insolvency, registering property, protecting minority investors, trading across borders, dealing with construction permits, getting electricity, paying taxes, and contracting with the government. In Morocco, employing workers and contracting with the government were not included.

- There was a three-year delay in naming the Competition Council Board of Directors after the 2014 legal reforms. According to the Economic Competitiveness Support Program Implementation Completion and Results Report (World Bank 2017), the Competition Council permanent staff carried out approximately 30 internal investigations during the interim period, but these investigations could not be made public nor could any formal decision be made until the new board was formally appointed.

- In 2019, the World Bank and the Competition Council organized a national seminar—The Revitalization of the Competitive Ecosystem in an Open Morocco. In 2020, they organized three workshops for the Competition Council officials.

- See World Development Indicators 2020.

- The National Financial Inclusion Strategy includes eight pillars: (i) initiating mobile payments; (ii) transforming microfinance; (iii) making insurance more inclusive; (iv) increasing the financial inclusion of micro, small, and medium enterprises and start-ups; (v) digitizing government-to-person payments; (vi) downscaling banks to accelerate the financial inclusion of target beneficiaries, including micro, small, and medium enterprises; (vii) enhancing financial education; and (viii) coordinating stakeholders to implement financial inclusion initiatives and monitor their progress.