The World Bank Group's Engagement in Morocco 2011-21

Chapter 1 | Introduction

This Country Program Evaluation assesses the development effectiveness of the World Bank Group’s support to Morocco between fiscal year (FY)11 and FY21. Specifically, it investigates the Bank Group’s effectiveness in solving four systemic obstacles to Morocco’s development that were identified by a national Commission Spéciale sur le Modèle de Développement (Special Commission on the Development Model). The commission was tasked by His Majesty King Mohammed VI to find the root causes of Morocco’s development challenges during the 2010s (CSMD 2021). The commission identified the four obstacles as (i) an incoherent public policy with the country’s development aspirations (chapter 2); (ii) an uneven economic playing field that favors established firms and state-owned enterprises (SOEs), creates nonproductive rent-seeking behaviors, and discourages new entrants (chapter 3); (iii) weak policy implementation caused by the public sector’s weak capacity to carry out reforms (chapter 4); and (iv) weak citizen and subnational participation in the country’s development (chapter 5). The Country Program Evaluation evaluated the Bank Group’s ability to overcome these obstacles across three outcome areas: (i) private sector–led growth that absorbs a growing labor force, (ii) inclusive human capital formation and protection and participation in the labor force, and (iii) climate change resilience and sustainable water resource management.

The report is organized around the four systemic obstacles to Morocco’s development. This first chapter introduces Morocco’s development context—including the country’s development trajectory and the Bank Group’s general role in that trajectory—before briefly reviewing the evaluation’s methodological framework. Chapter 2 investigates how the Bank Group shaped national policies and impacted Morocco’s development agenda. Chapter 3 discusses how the Bank Group contributed to leveling the playing field for micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs). Chapter 4 assesses the Bank Group’s support for effective policy implementation and service delivery. Chapter 5 explores the Bank Group’s efforts to increase Moroccan citizens’ participation in civic and economic life and subnational territories’ participation in the development process. Chapter 6 provides practical lessons to inform the Bank Group’s future engagement in Morocco. Outcome boxes in chapters 3, 4, and 5 summarize findings for the three outcome areas.

Morocco’s Development Trajectory

Morocco achieved undeniable development gains in the 2000s after the economic volatility of the 1990s, but challenges remain. In the 1990s, Morocco embarked on an ambitious program of structural reforms and macroeconomic stabilization through free trade agreements, financial sector liberalization, and state-owned asset privatization. However, frequent droughts led to high volatility in Morocco’s economically important agriculture sector. As a result, yearly gross domestic product (GDP) growth rates in the 1990s were also volatile, varying from −5.4 percent to +12.4 percent, with an average annual growth rate of 3 percent. Following the accession to the throne by His Majesty King Mohammed VI in 1999, Morocco undertook additional economic and institutional reforms. It gradually liberalized its economy, privatized some public enterprises, diversified its economy to be less vulnerable to exogenous shocks, and improved access to public services (such as water, education, and electricity). These changes contributed to stronger and less volatile growth,1 averaging about 4.9 percent a year from 2000 to 2010 (figure 1.1). In addition, poverty rates fell from 15 percent in 2001 to less than 5 percent in 2013 (World Bank 2020b), and extreme poverty was practically eradicated. Between 2007 and 2014, the consumption rate for the bottom 40 percent grew faster than it did for the rest of the population. However, inequality remains a challenge in Morocco, and its Gini coefficient has barely moved in 25 years—it was 39.4 in 1998 and 39.5 in 2022. Likewise, poverty is still prevalent in rural areas, where poverty reduction is twice as slow and the poverty rate is twice as high as those at the urban and national levels. In 2018, the rural population accounted for 80 percent of the national population, showing a wide center-periphery wealth gap (World Bank 2022c).

The Arab Spring contributed to far-reaching governance changes in Morocco. In early 2011, Moroccans took to the streets to call for change. The strong growth and prudent economic management of the previous decade failed to deliver jobs and opportunities, especially for youth. In response to the events, the king launched a broad program of reforms, and the country adopted a new constitution by referendum in July 2011. The reforms strengthened the powers of the parliament and the head of government and reinforced the independence of the judiciary. The constitution enshrined citizen engagement and decentralization. The late-2011 elections ushered in a new government coalition led, for the first time, by the moderate Islamist Justice and Development Party. The new government launched a series of sector strategies to boost the country’s economic performance, but growth and job creation slowed with the eurozone crisis and regional instability. As a result, social discontent lingered throughout the decade and led to sporadic violence, such as in the Rif region in 2016–17 and in major cities in 2018.

COVID-19 significantly impacted Morocco’s society and spurred significant social protection and health reforms. In 2020, COVID-19 triggered the most important economic contraction since record keeping began. By the spring of 2021, some sectors began to recover as vaccines were rolled out, and demand rebounded in southern Europe for Moroccan products. The authorities acted promptly to address the health emergency, and by March 2022, 64 percent of the Moroccan population, including nearly all people over 60 years of age, were fully vaccinated compared with just 40 percent of the Middle East and North Africa Region’s total population. The pandemic shock spurred significant reforms in the social protection system and health sectors that are under implementation.

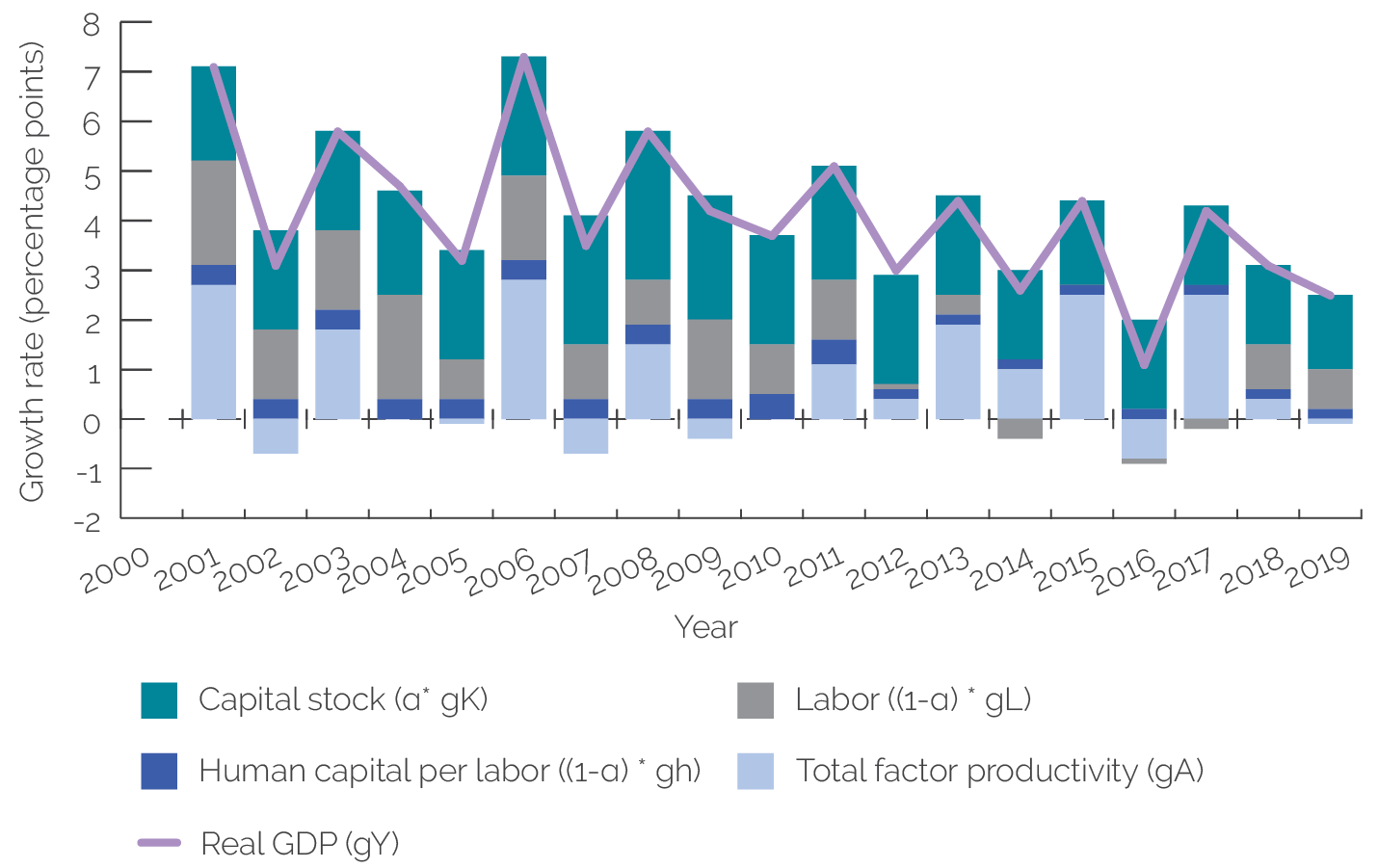

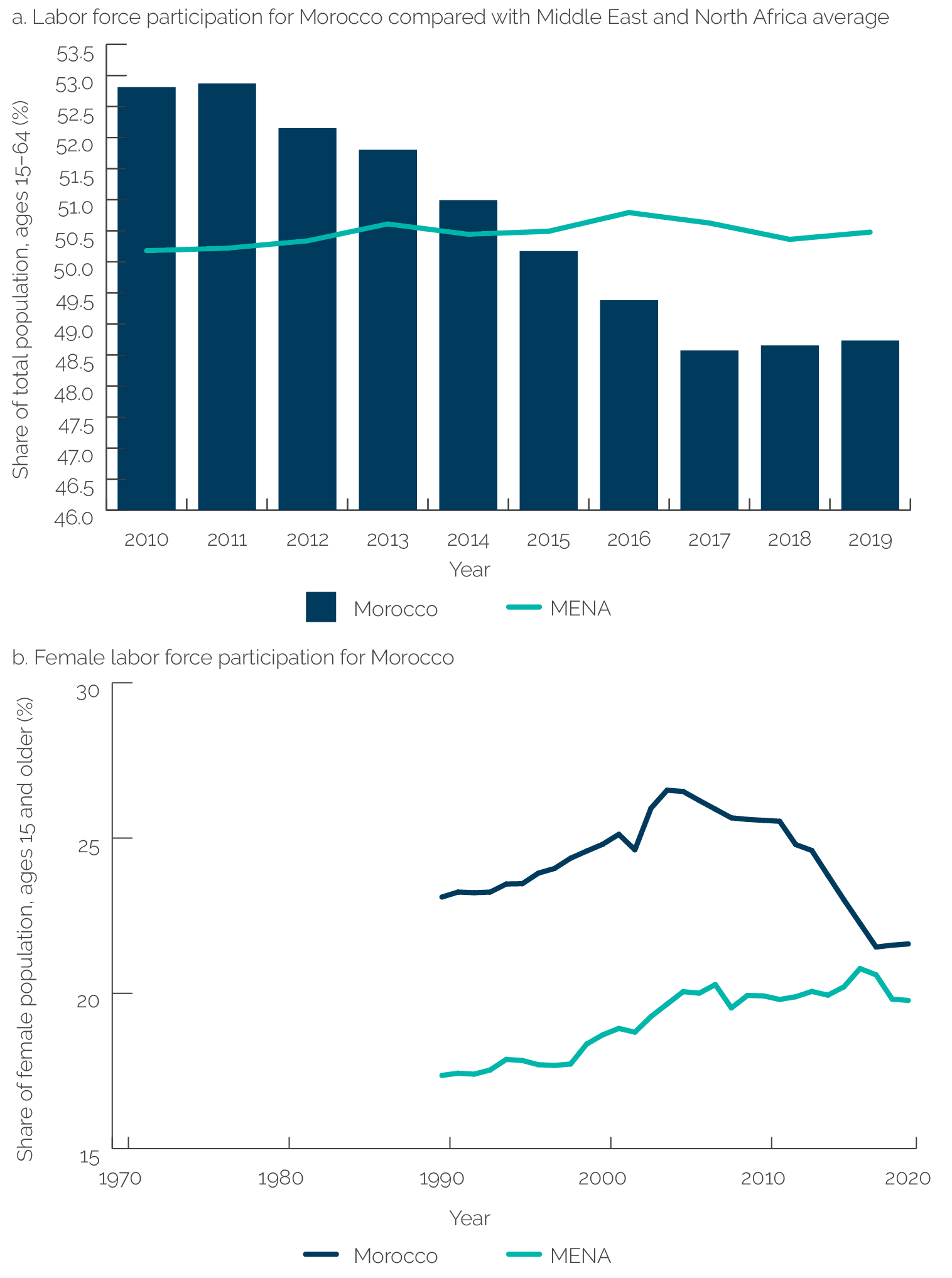

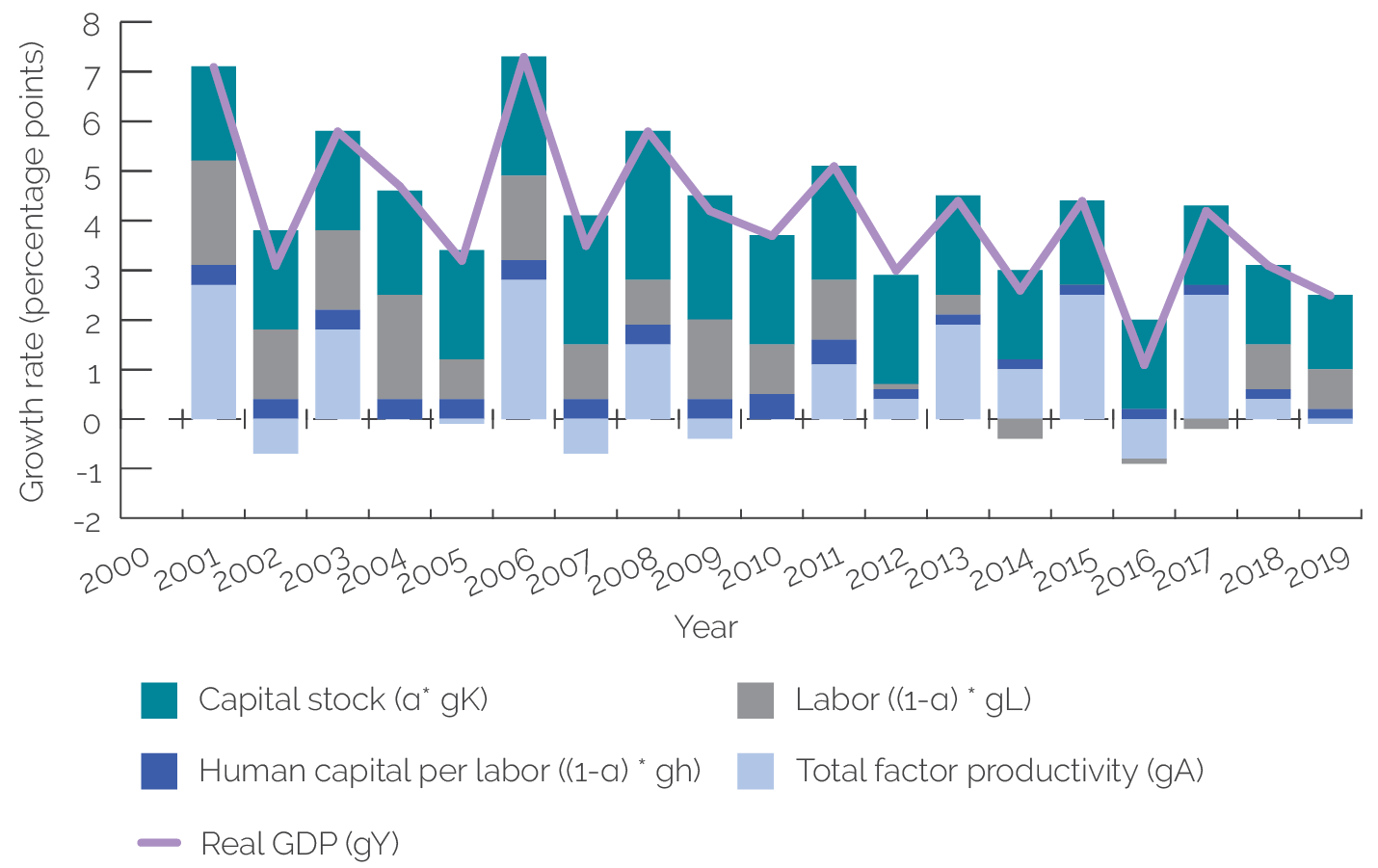

Morocco’s economic growth slowed at the same time as these political changes were taking place, despite one of the highest public investment rates in the world. Morocco’s gross capital formation averaged 35 percent from 2008 to 2020, placing its public investment rate among the top 10 percent of countries worldwide. This high investment rate was driven by major public investments; large infrastructure projects, such as the Tangier-Med port and the high-speed train between Tangier and Casablanca; and ambitious sectoral strategies—most notably, the 2008–20 Green Morocco Plan (Plan Maroc Vert; PMV)—which aimed to reform agricultural policy and accelerate agricultural productivity. In addition, the Emergence Plan (adopted in 2005) attempted to attract investment to high-potential export sectors in aeronautics, agribusiness, phosphate mining, and the automotive industry. Despite the high investment, Morocco’s average economic growth declined to only 3.4 percent per year between 2010 and 2019. Figure 1.1 shows that Morocco maintained its total productivity growth during this period (purple line), but employment growth was only 25 percent of its rate from 2000 to 2009 (gray) and capital growth was only 75 percent of its rate from 2000 to 2009 (teal). Figure 1.2 shows the significant decline in labor force participation, particularly among youth and women, over the past decade. Four of five women in Morocco are neither employed nor looking for a job, and the unemployment rate is 20 percent for young people and 25 percent for young graduates. Moreover, most youth and women are employed in informal, insecure, poorly paid, and low-quality jobs (World Bank 2018).

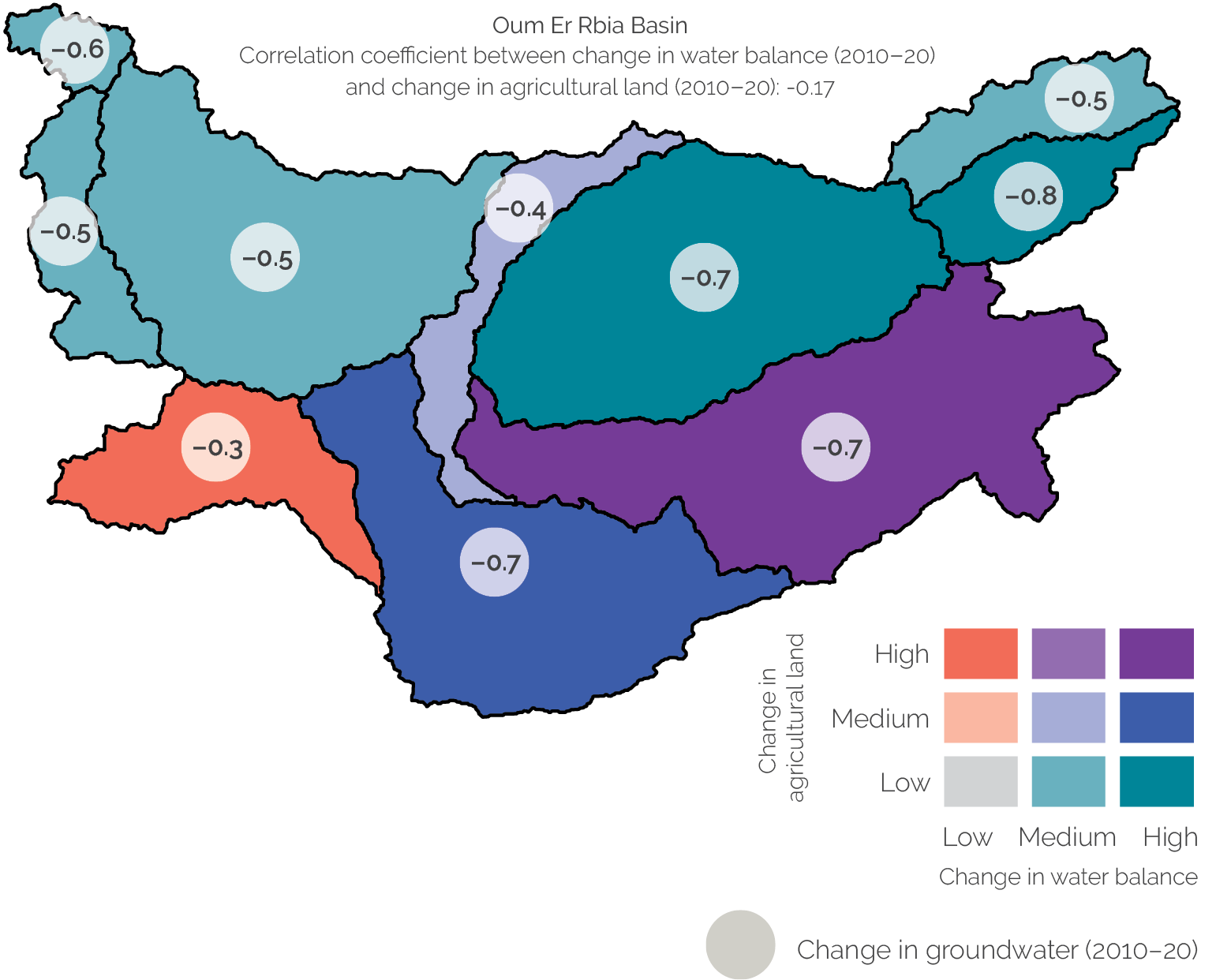

Morocco’s development has been hindered by climate change and low human capital formation. Climate change is exacerbating Morocco’s already high levels of water stress as droughts become more frequent and Morocco’s landmass becomes more arid, especially in southern regions. This surface water scarcity, combined with insufficient water use regulation, contributed to the overexploitation of groundwater, which triggered changes to agricultural land (see figure 1.3). Despite the greater overall aridity, climate change also increases the intensity of floods, especially in the economically vibrant northern coastal regions. According to the World Bank’s probabilistic evaluation of disaster risks, the country has annual average losses from natural catastrophes of over $800 million (World Bank Group and GFDRR 2018). In response, Morocco has developed an ambitious strategy to fight the effects of climate change by investing in renewable energy and transitioning to a low-carbon development model (Berahab et al. 2021). The PMV also included measures that encouraged farmers to adapt to climate change, for example, by incentivizing “direct seeding” for faster-maturing crops or growing tree crops instead of cereals to preserve soil health. Despite significant improvements in primary and secondary school enrollment, Morocco’s low human capital formation is hindering its development. Learning outcomes continue to be a concern, with a large proportion of children unable to read and comprehend simple text. According to the World Bank Human Capital Index, in 2019, 66 percent of 10-year-olds in Morocco did not achieve the expected level of reading, which was 10 percentage points below the average for other lower-middle-income countries. COVID-19 has likely exacerbated these learning losses.

Figure 1.1. Contributions of Labor, Capital Stock, and Other Factors (Total Factor Productivity) to Real Gross Domestic Product Growth, 2000–19

Source: Independent Evaluation Group staff estimates based on World Development Indicators data.

Note: GDP = gross domestic product.

In May 2021, Morocco adopted its New Development Model (NDM). The report offers a thorough and frank diagnosis of the perennial problems that explain Morocco’s development slowdown and lays out several priorities for the country for the period 2021–35. The NDM seeks transformations across four domains: the economy, human capital, inclusion and solidarity, and territories and sustainability. In addition, the model calls for a stronger partnership between the state and citizens and introduces a new set of principles to guide concerted actions among a wide range of stakeholders. These principles include achieving results and concrete impact for citizens, promoting innovation and seeking systems approach through partnership, and strengthening capacity and subsidiarity across levels of governments. Finally, the model seeks to activate two levers to implement these changes: a renewed administrative apparatus and digital technologies (CSMD 2021).

Figure 1.2. Labor Force Participation Rate

Source: ILOSTAT (database) 2020, International Labour Organization.

Note: Share of the female labor force, ages 15 and older, that is economically active; labor force is defined as all people who supply labor to produce goods and services. Data are a weighted average. The International Labour Organization estimates are harmonized to ensure comparability across countries and over time by accounting for differences in data sources, the scope of coverage, the methodology, and other country-specific factors. The estimates are based on nationally representative labor force surveys, with other sources (population censuses and nationally reported estimates) used only when no survey data are available. Data were retrieved on June 15, 2021. MENA = Middle East and North Africa.

Figure 1.3. Agricultural Land Changes and Water Balance Changes in the Oum Er Rbia Basin, 2010–20

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: The correlation coefficient between the change in water balance (2010–20) and the change in agricultural land is −0.17. The Country Program Evaluation team used a geographic information system model to estimate the water budget and assess changes in arable land and groundwater levels in Morocco’s Oum Er Rbia basin. The water budget accounts for the water that flows in and out of a specific area. Appendix A provides more details. The following formula estimates changes in the water budget between 2010 and 2020: Water budget = Precipitation − Evapotranspiration − Runoff. This map was cleared by the World Bank Group cartography unit.

The World Bank Group’s Role in Morocco’s Development

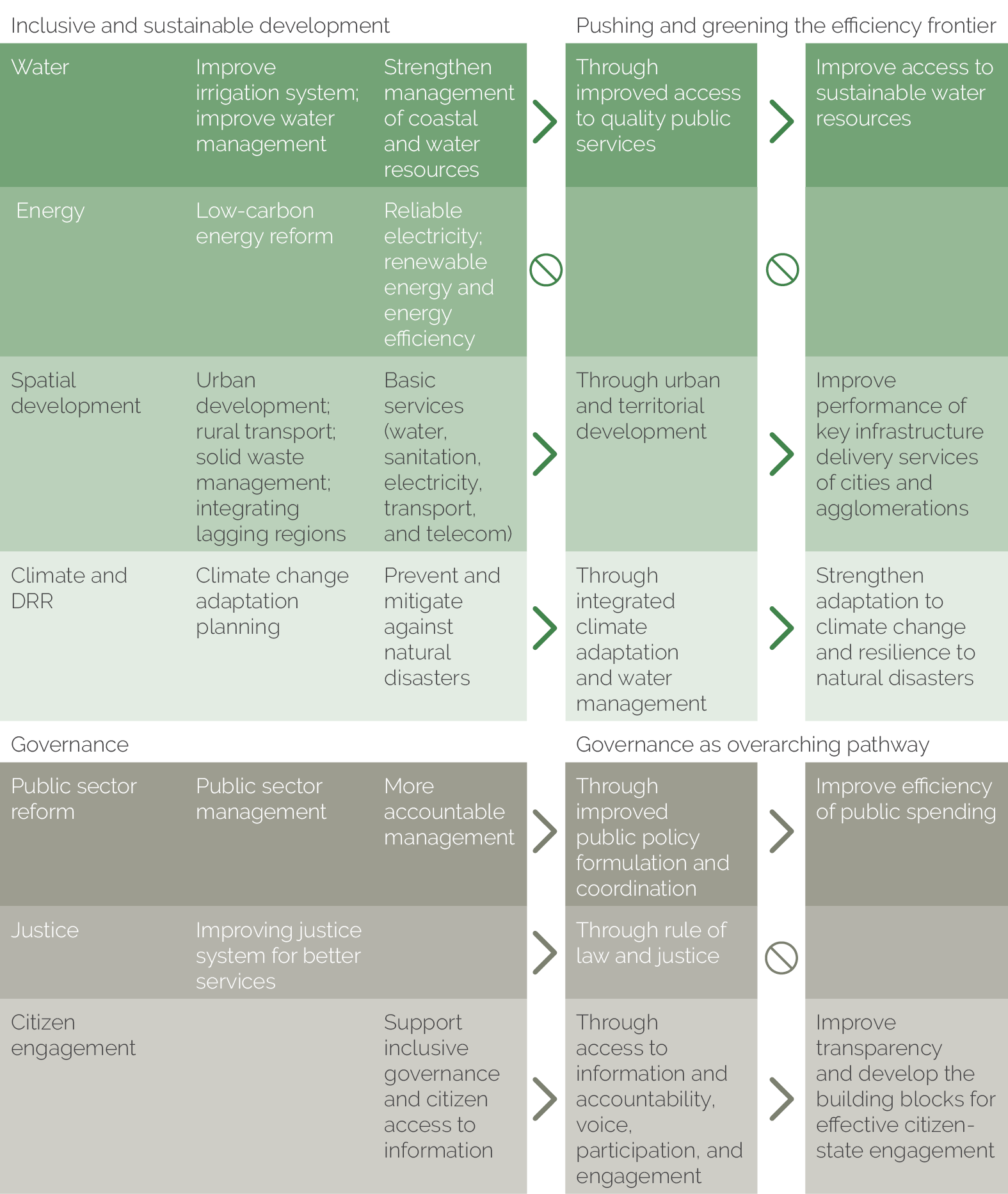

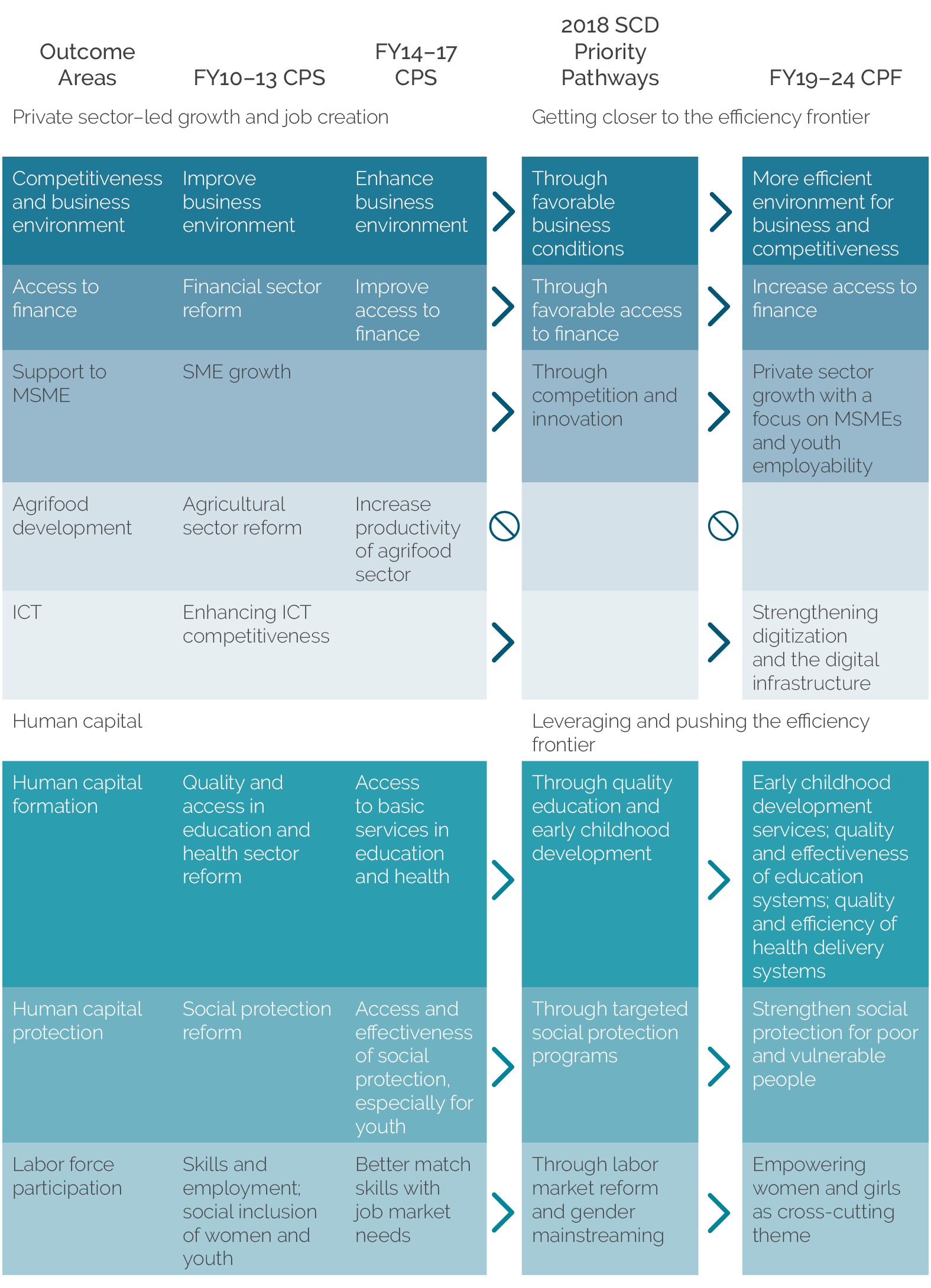

The Bank Group’s strategy in Morocco shifted over the evaluation period from an opportunistic approach to a more selective one. The three main strategy documents during this period included the FY10–13 Country Partnership Strategy (CPS), the FY14–17 CPS, and the FY19–24 Country Partnership Framework (CPF; figure 1.4 and appendix E). The International Finance Corporation (IFC) developed its own country strategy in FY19. The Bank Group also produced three core diagnostics: the 2017 Country Economic Memorandum (CEM), the FY18 Systematic Country Diagnostic (SCD), and the FY19 Country Private Sector Diagnostic. The FY10–13 CPS was very broad with 44 objectives spanning 12 outcome areas (appendix E; World Bank 2009). It responded to the government’s demand for increased financing and analytical work in all sectors with little selectivity. The CPS’s 2012 Mid-Term Review responded to the Arab Spring and constitutional changes by focusing more on inclusion, governance, and citizen voice (World Bank 2012a). After its publication, there was a gradual effort to increase selectivity. First, the FY14–17 CPS (World Bank 2014b), which was informed by a 2014 CPS Completion Report Review (World Bank 2014c), had a narrower scope than the previous CPS, with only 12 objectives across three outcome areas. Despite this strategic refocusing, the Bank Group’s project portfolio continued to grow because of the government’s demand for single-sector development policy financing (DPF). Second, the 2016 Performance and Learning Review introduced more selectivity (World Bank 2016b). By then, the growing portfolio faced challenges from declining disbursement ratios, deteriorating implementation ratings, and several unsatisfactory investment projects at closing. The World Bank’s newly appointed country director conducted the 2016 Performance and Learning Review and a portfolio deep dive exercise jointly with the government and, in response, put in place several mechanisms to increase the selectivity of investments, including readiness and governance filters. As a result, the country program dropped or paused several work areas. For example, new water sector support was withheld until water social safeguard issues on land acquisition and compensations were addressed, and justice sector work and anticipated support for tourism diversification and information and communication technology were canceled. This was, in part, to make space for more programing on jobs, governance, and human capital, as suggested by the 2015 Middle East and North Africa Regional strategy (Devarajan and Mottaghi 2015), which emphasized social contracts, and by ongoing work on the CEM. Third, informed by the 2018 SCD (World Bank 2018), the 2019 CPF continued this trend toward greater selectivity, keeping to 12 objectives and three outcome areas but narrowing its engagement within those outcome areas (World Bank 2019a). For example, the 2019 CPF moved away from the broad support for basic service deliveries that was part of the previous strategy and focused mostly on water services. Likewise, over the same period, the country program’s strategy evolved from a broad pursuit of urban and territorial development to a clear focus on improving infrastructure in cities and urban agglomerations.

Figure 1.4. The World Bank Group’s Engagement in Morocco, Fiscal Years 2010–20

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: CPF = Country Partnership Framework; CPS = Country Partnership Strategy; DRR = disaster risk reduction; FY = fiscal year; ICT = information and communication technology; MSMEs = micro, small, and medium enterprises; SCD = Systematic Country Diagnostic; SME = small and medium enterprise.

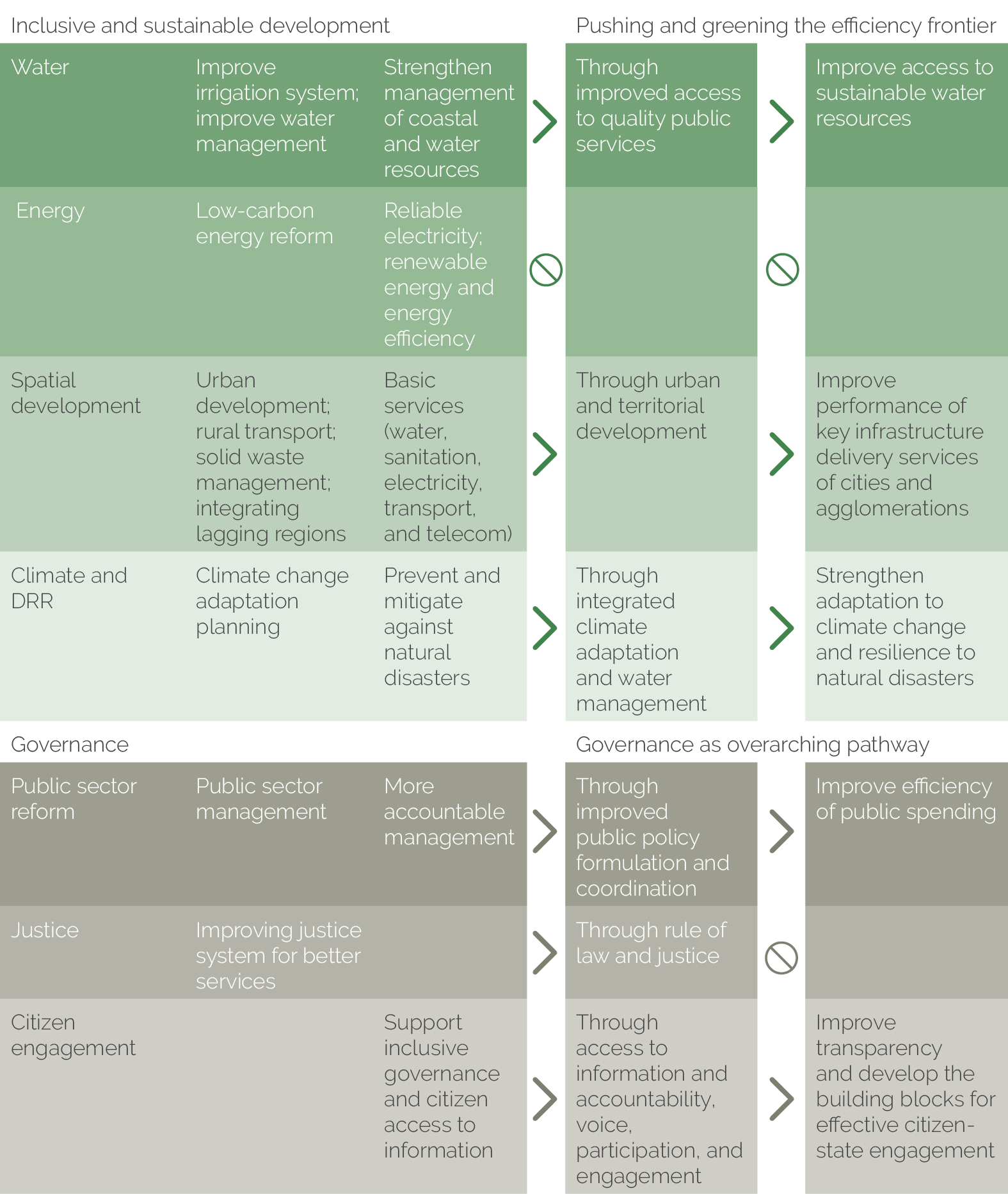

The World Bank’s choice of lending instruments evolved with its strategy, shifting from instruments that achieved reforms to instruments that supported implementation and results management (figure 1.5). From FY11 to FY21, the Bank Group committed $11.2 billion to Morocco, almost half of which was delivered through budget support instruments (table B.1). During the 2000s, investment project financing (IPF) was the most common instrument. However, during the FY10–13 strategy period, the World Bank preferred DPF to respond to the government’s desire to develop first-generation sector policies. As a result, single-sector development policy operations (DPOs) became the World Bank’s lending instrument of choice. DPF was also consistent with other donors’ strategies, particularly the advanced status agreement between the European Union (EU) and Morocco, and led the World Bank to deliver several DPOs jointly with other donors. However, the 2014 CPS Completion Report Review cautioned against over-relying on single-sector DPOs, especially as Morocco struggled to implement reforms and began embarking on second-generation reforms that were more cross-sectoral in nature. This warning was heeded during the FY14–17 strategy period as the World Bank began to rely more on Program-for-Results (PforR) operations, which are geared toward outcome-centered programming in line with Morocco’s organic law on performance budgeting. By the most recent strategy period (FY19–24), PforR replaced DPF as the instrument of choice across almost all sectors, with seven PforR operations approved compared with only three DPF activities approved (table B.1). In addition, the number of IPF activities declined from 25 during FY11–14 to only four during FY18–21, which was partly the result of the poor performance of IPF activities, especially grant-funded investments, as highlighted in the 2016 Performance and Learning Review. The World Bank ramped up its analytical work over the evaluation period, from 23 advisory services and analytics (ASA) activities in FY11–14 to 48 in FY18–21. The World Bank also became more strategic in its use of ASA, from providing ASA on demand to anchoring ASA under specific strategy pillars.

IFC used both investments and advisory services to promote private sector development in Morocco. IFC’s investments during FY11–14 predominantly involved equity and indirect equity financing. However, IFC’s instrument mix shifted toward debt investments starting in FY14. Advisory services represented almost 40 percent of IFC’s operations in FY11–14, but this increased to 58 percent in FY18–21, particularly after the release of IFC’s new country strategy in 2019 (appendix B, table B.1). A quarter of IFC’s advisory services projects were implemented jointly with IFC’s investment projects that had the same development objectives.

The Bank Group did not have an explicit partnership strategy with other development financiers in Morocco but sought out opportunities to engage in cofinancing arrangements. The three country strategies are rather silent on the Bank Group’s strategic positioning among Morocco’s other development partners. However, all of the Bank Group’s strategy documents acknowledge the importance of coordinating its budget support to the government with other financiers. For example, during the FY10–13 strategy period, the World Bank coordinated its budget support with the EU in five sectors for which the government was developing sector strategies. In addition, there are a few exceptions in which the Bank Group’s strategic priority areas explicitly considered the work of Morocco’s other development partners. One such example was in the FY19–24 CPF (World Bank 2019a), where the Bank Group justified its decision not to engage in rule of law issues, even though they were highlighted in the 2018 SCD, because the EU plays a prominent role in this area and because the World Bank’s past justice sector engagement was not successful (as discussed in chapter 5). Toward the end of the evaluation period, the World Bank also stepped up its convening role. For example, in 2018, the World Bank, along with the African Development Bank and the United Nations Development Coordination Office, reinstated a formal donor coordination mechanism and convened regular meetings with Morocco’s main bilateral and multilateral development partners (Le Groupe Principal des Partenaires; Group of Main Partners). The World Bank also seized the opportunity to build synergies with other partners’ agendas. For instance, in 2019, the World Bank coordinated the design of its IPF on youth employment with the French Development Agency.

Figure 1.5. Evolution of the World Bank’s Financing Instruments, Fiscal Years 2011–21

Source: Independent Evaluation Group portfolio review and analysis.

Note: Before FY14 = activities active during FY11–21 but approved before FY14; FY14–17 = activities approved between FY14 and FY17; FY18–21 = activities approved between FY18 and FY21. DPF = development policy financing; FY = fiscal year; IPF = investment project financing; PforR = Program-for-Results.

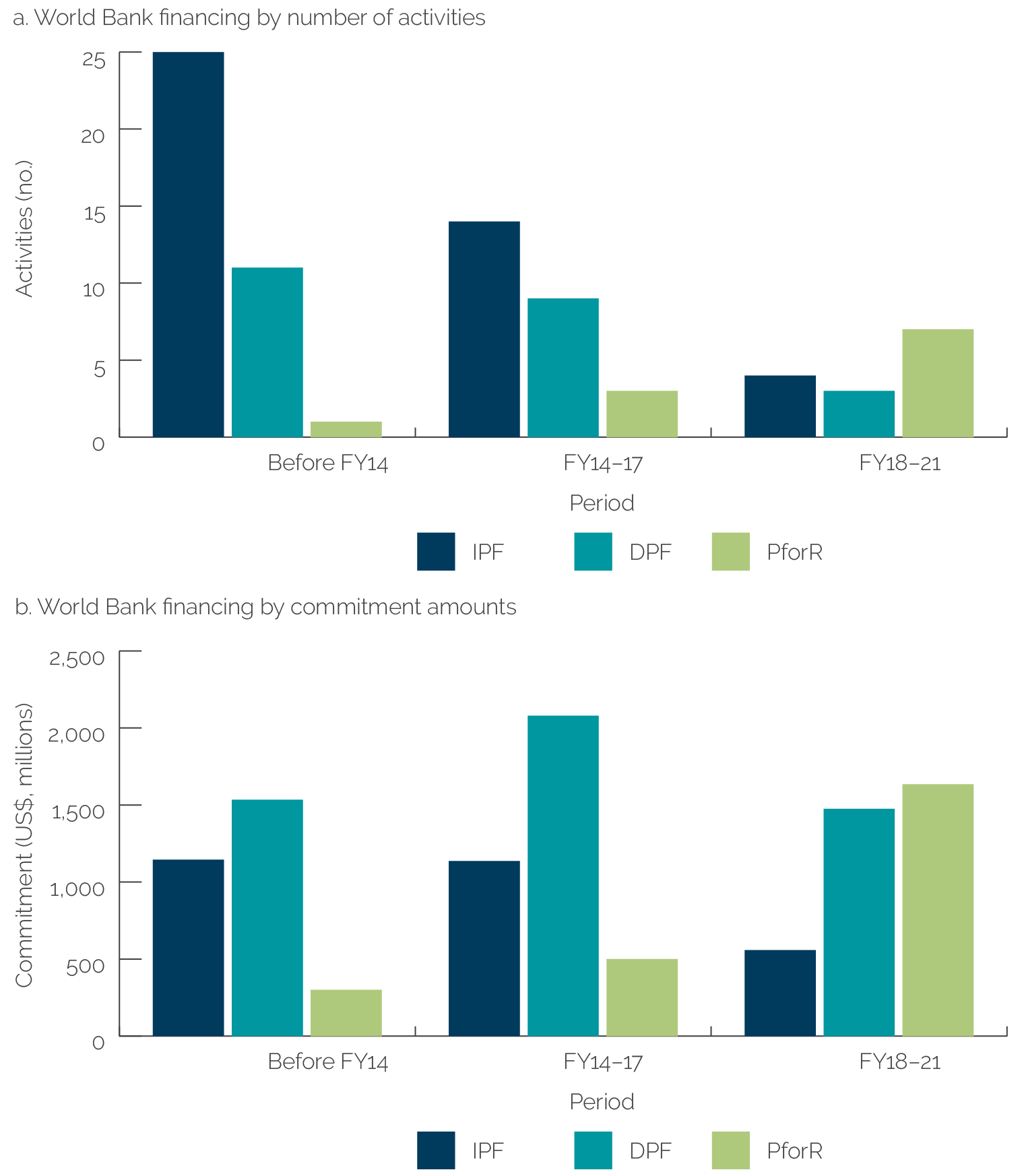

The average overall development outcome rating for World Bank–supported projects that closed during the evaluation period was moderately satisfactory. This rating is the same as the average rating for all projects in the Middle East and North Africa Region during that time. The Independent Evaluation Group evaluated 39 (74 percent) of 53 closed projects. Of these, about 60 percent were rated moderately satisfactory compared with 50 percent in Middle East and North Africa, and about 30 percent were rated satisfactory or above compared with about 33 percent in Middle East and North Africa. Only about 10 percent of projects in Morocco were rated unsatisfactory or below. At a sector level, operations were more highly rated in the sectors of Finance, Competitiveness, and Innovation; Energy and Extractives; Transport; and Urban, Disaster Risk Management, Resilience, and Land. Poorer-performing sectors included Agriculture and Food, Water, and Governance (figure 1.6 and appendix B). Average ratings were not computed for IFC because only four IFC investments and three IFC advisory services were subject to evaluations during the evaluation period.

Figure 1.6. Overall Outcome Ratings for World Bank Operations, Fiscal Years 2011–21

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: The chart shows Implementation Completion and Results Report Review development outcome ratings for projects that closed between fiscal years 2011 and 2021 (N = 39 closed projects).

Evaluation Framework

This report’s evaluation framework relied on four design principles. First, it applied a theory-based evaluation of the Bank Group’s contribution to country outcomes. This approach was appropriate because the Bank Group primarily uses indirect pathways of policy influence. Second, the framework used causal analyses “within” and “across” outcome areas. The team used the “within-case” analysis, including process tracing, for an in-depth study of the Bank Group’s actions that led to changes in important outcome areas. The team used the “across-case” analysis to draw general patterns across all outcome areas. Third, the framework systematically applied five steps to evaluate the Bank Group’s relevance and effectiveness across outcome areas (see the steps of the contribution analysis in box 1.1). Fourth, the evaluation framework used mixed methods to collect and analyze data and assess the value of the evidence. Box 1.1 briefly describes these methods, and appendix A describes them in detail, including how evaluation methods link to specific questions, and explains the evaluation’s limitations.

Box 1.1. Methodology

- The team conducted a contribution analysis for each outcome area. The analysis consisted of the following steps: (i) unpacking contribution pathways (16 pathways across the three outcome areas) and reviewing data and diagnostic documents to establish outcome trends; (ii) formulating a theory of change and mapping the sequence of applied instruments; (iii) analyzing the content in project documents, government reform documents, evaluations when available, press coverage, and civil society organization reports; (iv) conducting complementary interviews; and (v) comparing findings across outcome areas.

- The team conducted 120 interviews: 85 with World Bank Group staff, 10 with Morocco’s development partner organizations, and 25 with the Bank Group’s government counterparts.

- The team conducted an in-depth process-tracing study of the impacts from World Bank knowledge products on policy adoption. This study included the reconstruction of process theories using policy influence literature from a 10-year period and theory testing using evidence from interviews, media data, and high-level policy statements.

- The team conducted a targeted portfolio analysis of performance ratings, disbursement-linked indicators in Program-for-Results operations, and mainstreamed digital solutions.

- The team conducted a geospatial analysis of water balances for irrigation projects in the Oum Er Rbia basin.

- The team conducted a regional analysis of investments by the World Bank, Morocco’s development partners, and the government.

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

- Between 1990 and 2010, the share of agriculture in output barely changed, dropping from about 15 percent of gross domestic product in 1990 to 13 percent in 2010.