The World Bank’s Role in and Use of the Low-Income Country Debt Sustainability Framework

Chapter 3 | The World Bank’s Role in, and Contribution to, Long-Term Projections in Debt Sustainability Analyses

Highlights

As per the Low-Income Country Debt Sustainability Framework (LIC-DSF) guidelines, the World Bank is expected to take the lead in Debt Sustainability Analyses (DSAs) on longer-term growth prospects (and, when required, on assessing the investment-growth relationship). The extent to which this happens varied considerably across countries, with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in the driver’s seat for both medium- and long-term projections in the majority of DSAs (and countries). Only 10 percent of World Bank economists indicated that they led preparation of long-term macroeconomic forecasts, whereas another 31 percent indicated that they had significant contributions or shared responsibility with the IMF and 58 percent indicated they provided some comments and revisions.

Debt Sustainability Analyses for about half of the International Development Association (IDA)-eligible countries contained a substantive discussion of long-term growth and its drivers. The remainder had modest or no discussion of drivers of long-term growth. This is consistent with the finding that the majority of World Bank economists relied on historical trends (and, implicitly, past relationships between investment and growth) to project long-term growth rather than explicit assumptions about the future role of investment in driving long-term growth.

Similar to the broader sample, case studies illustrated a tendency for long-term growth assumptions to be largely consistent with historical averages, whereas fiscal assumptions were significantly more optimistic. There was a small increase in the degree of optimism in forecasts of average annual long-term real GDP growth across the three DSA preparation periods relative to historical performance. At the same time, compared with historical averages, long-term forecasts of the primary balance showed greater optimism. There was also increase in the standard deviation of projections for the primary balances, suggesting greater differentiation among country projections.

This section analyzes the quality and coherence of inputs into the LIC-DSF for which the World Bank is responsible. In doing so, it focuses on aspects for which the World Bank has the designated lead, including with respect to long-term projections of GDP growth, the investment-growth nexus, long-term primary balances, the incorporation of climate change assumptions, and debt data quality.

Long-Term Forecasts of GDP Growth

The LIC-DSF guidelines are clear that the World Bank is expected to take the lead on longer-term growth prospects that form part of LIC-DSAs. Survey evidence and case studies undertaken for this evaluation suggest that the interpretation of what this implies for World Bank inputs into the LIC-DSA varies considerably across World Bank staff working on different countries. Only 10 percent of World Bank economists indicated that they led preparation of long-term macroeconomic forecasts in DSAs, and another 31 percent indicated that they made significant contributions to, or shared responsibility with, the IMF. A further 58 percent indicated that they provided some comments and revisions. Case study evidence followed a similar pattern. For case study countries, the World Bank played a leading role in the articulation of long-term growth projections in Bhutan and the Democratic Republic of Congo and contributed to the projections in several others.

Forecasting long-term growth is inevitably more difficult and imprecise than medium-term forecasting, and more fundamental structural factors come into play over the long term. Preparing medium-term projections is already fraught with challenges (see box 3.1), and long-term projections are even more so. Yet, the World Bank, given its development mandate, is well positioned to inform long-term projections. In addition to macroeconomic variables of savings, investment, and productivity, long-term growth is influenced by factors such as human capital accumulation, demographics, labor force participation, and the impact of climate change. Although modeling long-term projections is fraught with challenges, the World Bank can play a prominent and even leading role in identifying the country-specific factors that will influence long-term growth and related variables and postulate their potential impact on debt sustainability. World Bank inputs can also be informed by the World Bank’s Long-Term Growth Model—an Excel-based tool that has already supported work in more than 45 countries, often to inform the World Bank’s Country Economic Memorandums and Systematic Country Diagnostics.

This evaluation does not assess the accuracy of the long-term growth projections (that is, greater than six years) used in LIC-DSAs. This would not be possible with only five years passed since the 2017 reform. Instead, it compares long-term GDP growth and primary balance projections used in LIC-DSAs with historical data. It draws on data from LIC-DSAs for 53 countries prepared over three different periods: 2015–17 (before the DSA reforms), 2018–19 (after the DSA reforms but before the COVID-19 pandemic), and 2020–22 (after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic). Because COVID-19 had a severe effect on growth and fiscal variables in many countries, an additional iteration for 2020–22 DSAs was undertaken to exclude the COVID-19 pandemic from the calculation of historical averages.

Box 3.1. Historical Bias in Macroeconomic Projections Underpinning Debt Sustainability Analyses

The World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) have previously identified significant biases in projections used in Low-Income Country Debt Sustainability Analyses (LIC-DSA; IDA and IMF 2017b). Biases in annual projections can have a substantial compounding effect in the long term. For example, GDP growth that is overestimated by 1 percentage point over 20 years can lead to underestimation of the debt-to-GDP ratio by 22 percentage points, whereas overestimating growth by 2 percentage points per year can underestimate the debt-to-GDP ratio by 49.8 percentage points. The 2017 review of the Low-Income Country Debt Sustainability Framework found that (i) forecast errors for public and external debt tended to increase over time, with the average absolute error rising to approximately 20 percentage points after seven years for both the public and the external debt-to-GDP ratios; (ii) errors reflected a clear optimism bias, with over three-quarters of larger deviations (of more than 15 percentage points) beyond the medium term being on the optimistic side; (iii) for public debt, forecast errors were mainly related to unexpected fiscal needs, including the materialization of contingent liabilities, rather than growth or other shocks, and forecast errors for external debt were mainly driven by unexpected financial flows (IDA and IMF 2017b).

The existence of optimism bias has also been identified in public debt forecasts contained in DSAs (Flores et al. 2021). Debt projections in the IMF World Economic Outlook made over the 2002–14 period exhibited a median forecast error of approximately 8 percentage points after five years. Notably, this optimism bias appears to have emerged beginning about 2007, with forecasts made thereafter exhibiting much larger errors. The authors found that optimism bias was greater for lower-income countries, oil exporters, countries with high growth volatility, and countries with already high debt ratios. Moreover, optimism bias tended to be larger when initial forecasts were for a reduction in the debt-to-GDP ratio.

The Independent Evaluation Group previously highlighted optimism bias in debt forecasts used in DSAs (World Bank 2021a). The Independent Evaluation Group noted that overoptimism reflected frequent underestimation of downside risks related to contingent liabilities of state-owned (SOEs) enterprises, or to shocks that were correlated, with compounding results. The case studies for this evaluation also illustrated this tendency (for example, debt-to-GDP ratios in Mozambique and Papua New Guinea rose sharply as a result of the realization of SOE borrowing, and in Zambia, the debt-to-GDP ratio rose as a result of procyclical policies and an overestimation of the growth impact from large public investment projects).

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

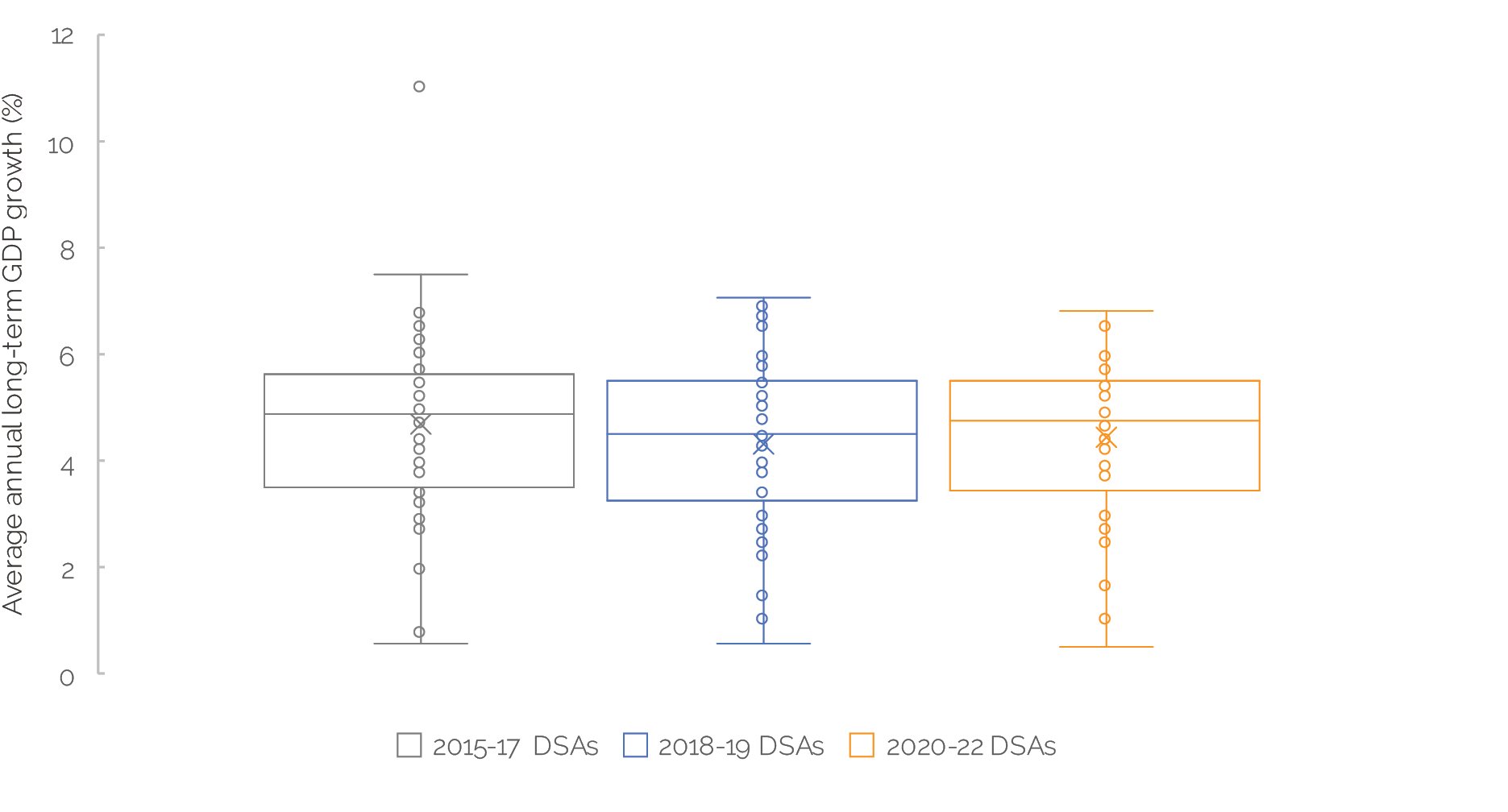

Forecasts of long-term growth changed modestly across the three DSA preparation periods relative to historical performance. The median forecast for long-term GDP growth declined from 4.9 percent to 4.5 percent between 2015–17 and 2018–19 before rising to 4.8 percent over 2020–22. At the same time, and despite the increase in uncertainty and volatility in the most recent period, the standard deviation of real GDP forecasts declined from 1.7 over 2015–17 to 1.5 over 2018–19 and 1.4 over 2020–22 (table 3.1 and figure 3.1).

Table 3.1. GDP Growth over Different DSA Preparation Periods for IDA-Eligible Countries

|

GDP Growth Statistic |

DSA Period |

|||||||||

|

Historical |

Medium-term projection |

Long-term projection |

||||||||

|

2015–17 |

2018–19 |

2020–22 |

(excl.COVID-19) |

2015–17 |

2018–19 |

2020–22 |

2015–17 |

2018–19 |

2020–22 |

|

|

Mean |

4.6 |

4.1 |

3.9 |

4.3 |

4.4 |

4.3 |

4.3 |

4.7 |

4.3 |

4.5 |

|

Median |

4.7 |

4.4 |

3.8 |

4.2 |

4.7 |

4.7 |

4.4 |

4.9 |

4.5 |

4.8 |

|

SD |

3.1 |

3.0 |

2.2 |

2.2 |

2.4 |

2.4 |

1.7 |

1.7 |

1.5 |

1.4 |

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: DSA = Debt Sustainability Analysis; excl. = excluding; GDP = gross domestic product; IDA = International Development Association; SD = standard deviation.

Figure 3.1. Distribution of Long-Term GDP Growth as Forecast for IDA-Eligible Countries over Different DSA Preparation Periods

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: DSA = Debt Sustainability Analysis; IDA = International Development Association.

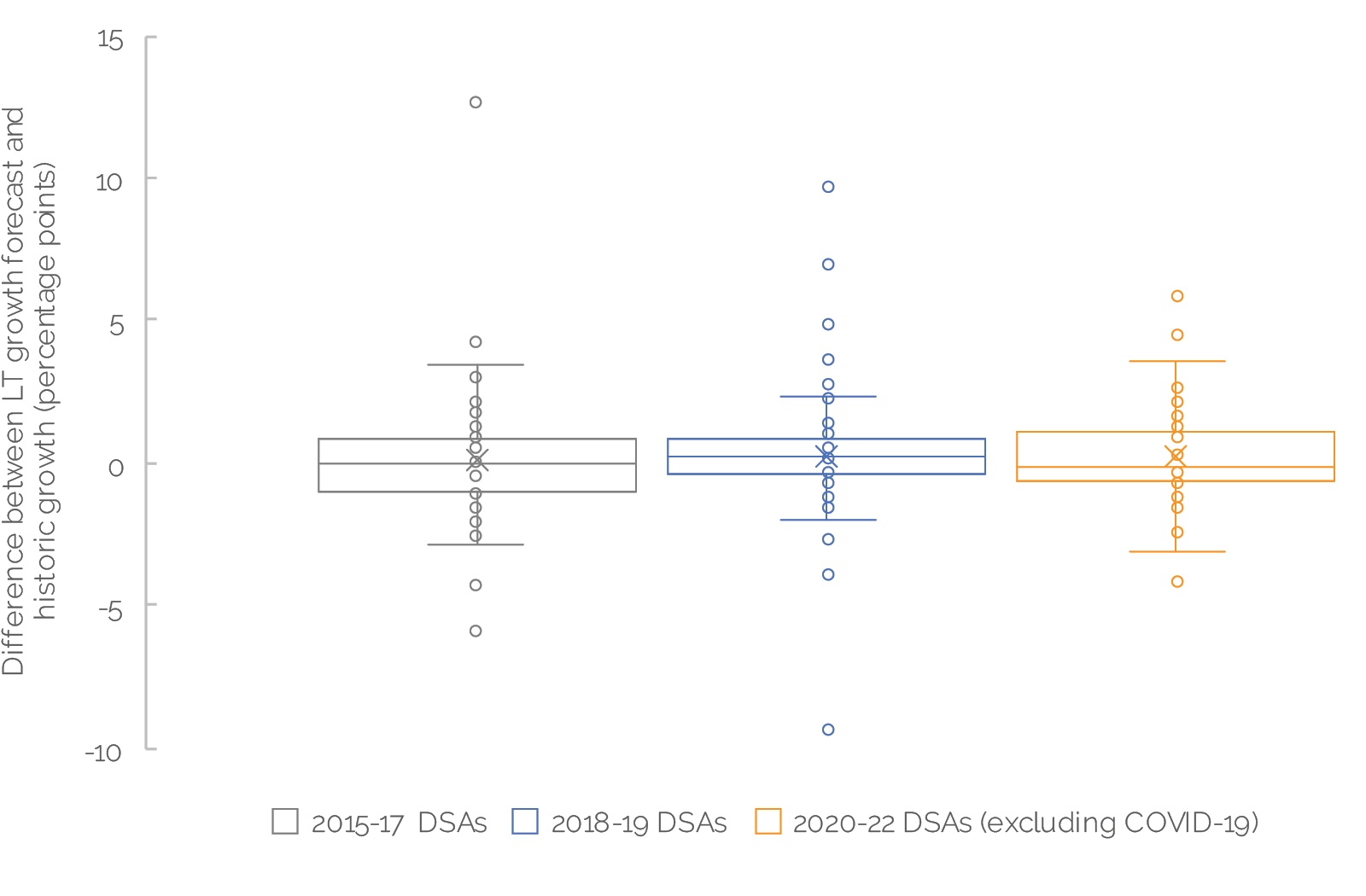

There was a small increase in the degree of optimism in average annual long-term growth projections relative to historical performance. There was some increase in the share of countries with long-term growth that was more than 1 percentage point more optimistic than average annual historical growth, from 21.2 percent over 2015–17 to 28.3 percent over 2020–22 (with COVID-19 years excluded from the historical average). The share of countries with long-term growth projections more optimistic than historical averages by more than 2 percentage points increased slightly from 11.5 percent to 13.2 percent (see figure 3.2, table 3.2, and appendix C for further details).

Figure 3.2. Distribution of Differences between Long-Term GDP Growth Forecasts and Historical Average Growth over DSA Preparation Periods

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: DSA = Debt Sustainability Analysis; LT = long term.

Table 3.2. Differences between Long-Term Projection and Historical Average GDP Growth over DSA Periods

|

GDP Growth Statistic |

DSA Period |

|||

|

2015–17 |

2018–19 |

2020–22 |

2020–22 (excl. COVID-19) |

|

|

Mean |

0.1 |

0.3 |

0.6 |

0.2 |

|

Median |

0.0 |

0.2 |

0.4 |

−0.2 |

|

SD |

2.6 |

2.6 |

1.7 |

1.7 |

|

Share less optimistic by at least 1 percentage point |

28.8 |

17.0 |

13.2 |

20.8 |

|

Share more optimistic by at least 1 percentage point |

21.2 |

22.6 |

34.0 |

28.3 |

|

Share less optimistic by at least 2 percentage points |

15.4 |

11.3 |

3.8 |

5.7 |

|

Share more optimistic by at least 2 percentage points |

11.5 |

13.2 |

18.9 |

13.2 |

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: DSA = Debt Sustainability Analysis; excl. = excluding; GDP = gross domestic product; SD = standard deviation.

Long-Term Forecasts of the Primary Balance

There have been marginal improvements in long-term forecasts of the primary balance. Median long-term forecasts of the primary balance have improved marginally from a deficit of 0.8 percent to 0.7 percent of GDP over the three DSA periods, whereas mean forecasts of the primary deficit have worsened from 0.9 percent of GDP to 1.2 percent of GDP. On the other hand, the standard deviation has increased from 1.6 in 2015–17 to 3.6 in 2018–19 and 4.7 in 2020–22, reflecting greater differentiation among countries (table 3.3 and figure 3.3).

Table 3.3. Long-Term Projections of Primary Balance over Different DSA Periods

|

Primary Balance Statistic |

DSA Period |

|||||||||

|

Historical |

Medium-term projection |

Long-term projection |

||||||||

|

2015–17 |

2018–19 |

2020–22 |

(excl.COVID-19) |

2015–17 |

2018–19 |

2020–22 |

2015–17 |

2018–19 |

2020–22 |

|

|

Mean |

−1.2 |

−1.6 |

−2.2 |

−2.2 |

−2.1 |

−1.3 |

−2.4 |

−0.9 |

−1.2 |

−1.2 |

|

Median |

−1.2 |

−1.8 |

−2.0 |

−2.0 |

−1.4 |

−1.4 |

−1.7 |

−0.8 |

−0.8 |

−0.7 |

|

SD |

3.5 |

3.0 |

4.9 |

5.2 |

5.8 |

3.6 |

6.0 |

1.6 |

3.6 |

4.7 |

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: DSA = Debt Sustainability Analysis; excl. = excluding; SD = standard deviation.

Figure 3.3. Distribution of Long-Term Primary Balance Forecasts over DSA Periods

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: DSA = Debt Sustainability Analysis.

However, compared with historical averages, long-term forecasts of the primary balance showed significantly greater optimism. Long-term forecasts of the primary balance over the three DSA preparation periods were compared with historical averages (see table 3.4, figure 3.4, and appendix C for further details). The share of countries for which long-term primary balance forecasts were more than 1 percentage point more optimistic than historical averages was relatively stable between 2015 and 2019 at about 43 percent but increased to 51 percent in 2020–22 DSAs (with COVID-19 years excluded from the historical average). The share of countries for which primary balance projections in DSAs were more than 2 percentage points more optimistic increased from 27 percent to 34 percent and then to 40 percent in 2015–17, 2018–19, and 2020–22 (with COVID-19 years excluded), respectively.

Table 3.4. Differences between Long-Term Projection and Historical Primary Balance over DSA Periods

|

Primary Balance Statistic |

DSA Period |

|||

|

2015–17 |

2018–19 |

2020–22 |

2020–22 (excl. COVID-19) |

|

|

Mean |

0.3 |

0.4 |

1.0 |

1.0 |

|

Median |

0.3 |

0.6 |

1.2 |

1.2 |

|

Standard deviation |

3.5 |

5.1 |

3.7 |

3.9 |

|

Share less optimistic by at least 1 percentage point |

32.7 |

28.3 |

20.8 |

24.5 |

|

Share more optimistic by at least 1 percentage point |

42.3 |

43.4 |

52.8 |

50.9 |

|

Share less optimistic by at least 2 percentage points |

19.2 |

15.1 |

13.2 |

15.1 |

|

Share more optimistic by at least 2 percentage points |

26.9 |

34.0 |

37.7 |

39.6 |

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: DSA = Debt Sustainability Analysis; excl. = excluding; SD = standard deviation.

Figure 3.4. Distribution of Differences between Long-Term Primary Balance Forecast and Historical Averages over DSA Periods

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: DSA = Debt Sustainability Analysis; LT = long term.

Assumptions about Long-Term Growth and the Investment-Growth Nexus

Although much of the attention in DSAs is on medium-term macroeconomic projections, longer-term assumptions about investment plans and climate change, and their impact on growth, are critical to assessing debt sustainability. This is even more so because substantial public investment and associated borrowing is often justified by a belief that they will enhance growth (relative to a counterfactual) over the longer term, including by adapting to climate change. Without investment in adaptation, the transition to a lower-carbon economy will be slowed, while economies will become more susceptible to climate change–related natural disasters. In this light, the evaluation assessed the clarity and credibility of assumptions about the drivers of longer-term growth in DSAs (particularly regarding the investment-growth nexus) and the expected impacts of climate change.

DSAs for about half of IDA-eligible countries contained a substantive discussion of long-term growth and its drivers. For each of the 66 LIC-DSA countries in the sample, the most recent DSA (through June 2022) was reviewed (five of these DSAs were one- to two-page streamlined reports for emergency operations during COVID-19 with limited discussion). An example of well-articulated assumptions includes Uganda’s March 2022 DSA that has a clear discussion of the drivers of long-term growth:

In the long-term, growth is also supported by other factors. Specifically, infrastructure constraints are addressed (e.g., there are currently major investments to improve transport connectivity, expand access to power, and enhance digital connectivity), agricultural productivity improves, and agro-processing trade and industries are further developed. Finally, Uganda is entering a demographic transition, which has great potential for accelerating growth in per capita terms and reducing poverty. Although fertility rates and the dependency ratio are still high, Uganda’s declining fertility rate and growing working-age population are gradually increasing the share of the working-age population and reducing the child dependency ratio. (IMF 2022e, 8)

Another example is Dominica’s January 2022 DSA:

In the long term, after 2026, the output growth is projected to gradually decline and to converge to a potential growth rate of 1.5 percent based largely on the implementation of the public investment program and resultant increased resilience, improved built infrastructure, a new international airport, and geothermal developments, all of which should support improved [long-term] growth potential. (IMF 2022b, 6)

On the other hand, about a third of the 66 DSAs had only modest discussions of drivers of long-term growth or had no discussion at all. Twelve DSAs only briefly mentioned long-term growth, without a discussion of drivers. DSAs for another 11 countries discussed medium-term drivers of growth but did not discuss drivers of long-term growth.

A survey of World Bank country economists indicated that historical growth trends were the most common method for determining long-term growth forecasts. When asked if explicit assumptions about the relationship between public and private investment and growth were articulated alongside long-term macroeconomic projections, 19 percent of respondents indicated “yes” and 48 percent indicated “somewhat.” When citing the basis for assumptions about long-term growth, just under three-quarters of respondents indicated that they had used historical trends, whereas 24 percent used a quantitative model to derive their long-term projections and 20 percent used analysis from a Country Economic Memorandum.

Interviews with World Bank staff in the context of country case studies similarly highlighted various means for forecasting long-term growth. About half of the nine country case studies mentioned using quantitative models. The remainder relied on historical averages. Several mentioned how the standard World Bank country macroeconomic modeling tool (the macroeconomic and fiscal model [MFMod]) projects only for the medium term and was therefore of limited use for the purposes of long-term projections.