The World Bank Group in Mozambique, Fiscal Years 2008–21

Chapter 3 | Support for Agricultural Productivity

Highlights

Increasing agricultural productivity can reduce poverty, as agriculture dominates Mozambique’s economy and is the main source of income for most poor people in the country. World Bank analysis identified six priorities as critical to improving agricultural productivity in Mozambique: (i) stimulate adoption of modern production technologies; (ii) improve rural infrastructure; (iii) facilitate access to markets; (iv) improve natural resource management; (v) reform land policies and administration; and (vi) correct gender disparities that undermine the ability of female farmers to make efficient use of resources and technologies.

The World Bank’s assistance during the Country Program Evaluation period started with a focus on technology adoption, irrigation, and institutional support. Later, support expanded to include market access, forestry, land administration, and rural roads. Together, this support addressed the major constraints identified by analytical work and various stakeholders. Gender inequality became part of World Bank support only later in the evaluation period.

There is no concrete evidence so far of increased agriculture productivity in provinces supported by the World Bank. The two completed agricultural investment projects initiated in the earlier part of the evaluation period did not achieve their objectives. Provincial-level productivity data do not show any significant improvements in provinces targeted by World Bank support. It is too early to determine the impact of the support initiated in the later part of the evaluation period, although one of the rainfed agriculture projects (Sustenta) is considered promising, and the government has declared its intention to use that project’s design as the basis for a national program.

Increasing agricultural productivity was key for reducing rural poverty, income inequality, and gender gaps in Mozambique. Low productivity kept most small-scale farmers trapped in poverty (World Bank 2020f, 8). This continues to be the case particularly for women, who engage in farming at a higher rate than men but do not receive a commensurate share of farm income or have access to improved technology (JICA 2015). Consequently, increased agricultural productivity has considerable potential to alleviate rural poverty and reduce income inequality in Mozambique.

Analytical Underpinnings

During the evaluation period, the World Bank produced a considerable body of analytical work to identify areas that are critical to increasing agricultural productivity in Mozambique. Mozambique—Beating the Odds: Sustaining Inclusion in a Growing Economy provided a comprehensive analysis of poverty and gender issues, with a heavy emphasis on the role of agriculture (World Bank 2008). This analysis was augmented in later years by other World Bank analyses on food security, land policy, public expenditures to support agriculture, gender, and growth corridors, all of which contributed to a better understanding of the challenges facing the sector and actions to address those challenges.1 The World Bank’s analytical work, together with academic literature and interviews of knowledgeable stakeholders, identified the following actions as critical to increasing agricultural productivity in Mozambique:

- Introduce improved agricultural technologies. Intensify agricultural research and support services, such as extension services and literacy training of farmers, to increase understanding and application of improved technologies.

- Improve rural infrastructure. Expand electricity services, provide reliable domestic water supplies, build and rehabilitate rural roads and small-scale gravity irrigation systems, and enhance internet technology to reduce the isolation of small-scale farmers from social services, input, and output markets.

- Facilitate agriculture product marketing. Facilitate access to local, national, and international agriculture product markets through efficient value chains.

- Enhance natural resource management. Introduce sustainable land and soil management through crop rotation programs that will conserve soil structure and retain soil fertility, thereby reducing, and ultimately eliminating, slash-and-burn agriculture that causes deforestation.

- Reform land policies and administration. Support regulatory reforms related to land use planning, land sales, and land leasing to increase average farm sizes and private sector investment.

- Correct gender disparities. Given the high proportion of women engaged in agriculture, address obstacles to increasing female agricultural productivity, in the context of the many other responsibilities in rural households and the gender-based violence that is common in Mozambique. Women have less access to land, lower literacy rates (Mozambique, Ministry of Education 2010), less formal employment, and lower remuneration for their labor than their male counterparts. Indeed, 90 percent of rural women are either unpaid for their work or are reimbursed informally (USAID 2019).

The World Bank produced a considerable body of quality analytical work on Mozambique’s agricultural sector during the evaluation period. Since FY08, the World Bank produced 17 major analytical pieces on agriculture and related subjects. The first report, Beating the Odds (World Bank 2008), published at the start of the evaluation period, was a comprehensive policy analysis of poverty and gender issues, with an emphasis on the role of agriculture in poverty reduction. It concluded that improved research and extension could grow the agriculture sector and reduce poverty by increasing farmers’ abilities to use new technologies and access markets. Other World Bank reports contributed to understanding the challenges facing the sector by focusing on land policy, growth corridors, food security, agricultural risks, and agriculture-related public expenditures. After 2015, the World Bank reviewed broader policy constraints to agricultural growth, emphasizing the role of agricultural productivity and private investment in transforming the sector while also carrying out a review of agriculture-related public expenditures, an economic memorandum focusing on rural infrastructure, and a 2020 flagship report on income growth and poverty reduction in agriculture. These reports identified challenges related to public budget allocations to the agriculture sector, shortcomings in rural infrastructure, land administration, and weak off-farm income-earning opportunities for rural households. Another influential report concluded that market access was critical to ensure that agricultural productivity would lead to increased rural incomes. As a result, market access became a regular theme for Bank Group–assisted agriculture investment projects in Mozambique in 2016 and beyond and represented an important addition from World Bank management’s earlier focus on technology and increased productivity.

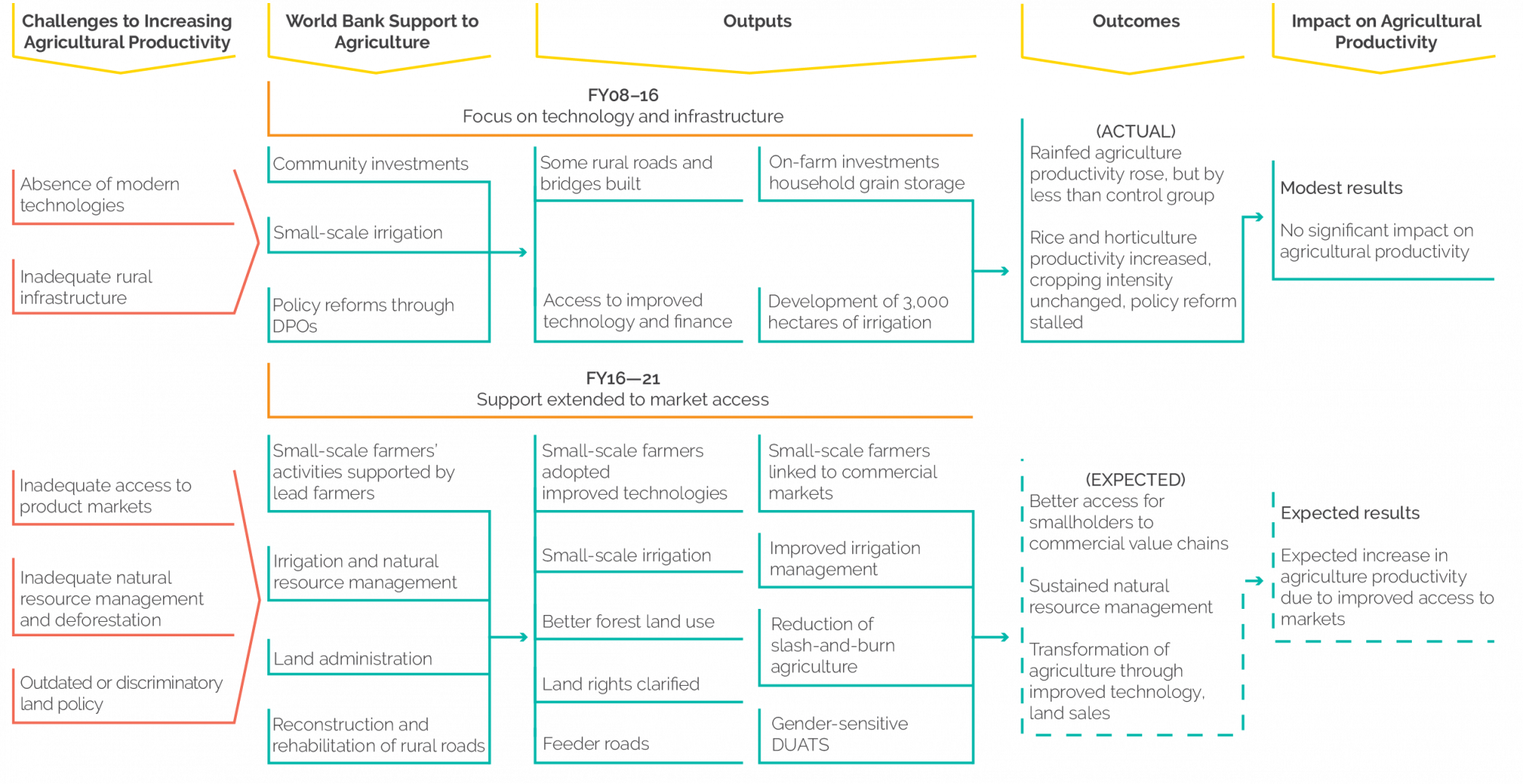

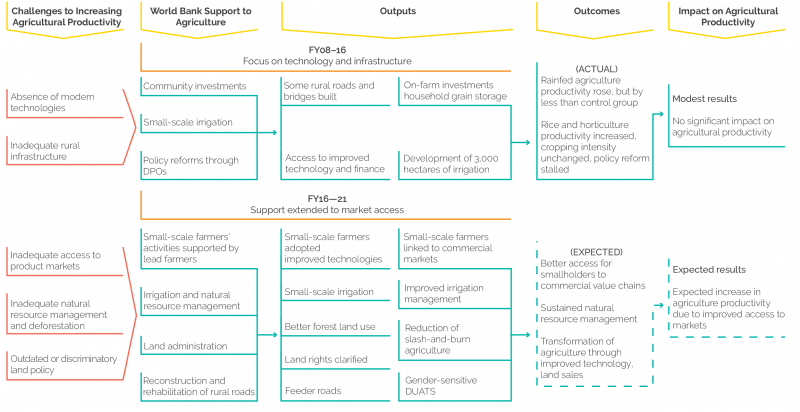

Drawing on these analytical underpinnings, all three Bank Group–supported strategies during the evaluation period sought to increase agricultural productivity. Figure 3.1 illustrates the evolution of World Bank support for increasing agricultural productivity. The CPS FY08–11 emphasized the need to increase investment in technology and infrastructure (irrigation and roads). The second strategy (CPS FY12–16) added improving land administration, facilitating access to rural finances, and supporting the decentralization of the agriculture sector administration.

The FY17–21 CPF expanded the strategy to include market access and commercial farming. “Republic of Mozambique: Agriculture and Rural Development Nonlending Technical Assistance—Synthesis Report” concluded that “increasing agricultural productivity can be effective in raising rural incomes only if farmers have access to output markets, knowledge, and modern technology” (World Bank 2016e).2 The 2020 Cultivating Opportunities for Faster Rural Income Growth and Poverty Reduction: Mozambique Rural Income Diagnostic came to similar conclusions (World Bank 2020a), identifying three priority actions as necessary to achieve rural income growth: (i) adopt improved agricultural technologies; (ii) enhance access to markets for surplus smallholder production; and (iii) reconstruct or rehabilitate strategic rural roads. Other analytical work such as the Republic of Mozambique Agrarian Sector Transformation: A Strategy for Expanding the Role of the Private Sector focused on the role of the private sector in transforming the agrarian sector so it would be more productive and competitive (World Bank 2019c). That analysis called for the government to stimulate private sector investment in agriculture by improving the business climate.

Relevance of World Bank Support

Investment projects addressed several constraints to the adoption of improved technology and rural infrastructure. These projects included community demand–driven investments (Market-led Smallholder Development in the Zambezi Valley Project; World Bank 2016b) and small-scale irrigation development (MZ PROIRRI Sustainable Irrigation Development; World Bank 2019b). The community-driven development model (focused on Sofala, Manica, and Zambezia) provided financing for rural roads and bridges chosen by communities and on-farm grain silos with the objective of increasing farm incomes through higher yields and reduced losses. The irrigation project, which focused on the same provinces, engaged farmers in participatory irrigation management to improve the enabling environment and strengthen institutions. The IFC contributed to investments totaling $32 million in a private company to finance improvements in wheat flour mills and pasta and biscuit production and for warehousing and trucks in Maputo, Beira, and Nacala between 2007 and 2012. In addition, IFC invested $7 million in grain handling and storage facilities at the port of Nacala in 2008.

Two DPOs contained prior actions to support policy and institutional reforms to increase agricultural productivity. The two DPOs sought to support agricultural technology, access to productive assets, and the monitoring of sector performance. Prior actions aiming at supporting technology adoption focused on Southern African Development Community–compliant policy and institutional reforms governing seed production, trade, quality control, and certification; ratification of the regulations for private sector–led fertilizer production and marketing; and plant breeders’ rights and procedures for the registration of fertilizers. Prior actions aiming at facilitating access to productive assets focused on regulations for irrigation, simplification of procedures for transferring rural land use rights (called Direito de Uso e Aproveitamento dos Terras; DUATs), development of rural financial services, and investment plans for agriculture. The third operation was canceled in the wake of the hidden debt crisis.

Figure 3.1. World Bank Support to Increasing Agricultural Productivity in Mozambique, Fiscal Years 2008–21

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: DPO = development policy operation; DUATS = land use rights; FY = fiscal year.

Since 2016, the World Bank has approved three investment projects that support improved market access. First, the Agriculture and Natural Resources Landscape Management Project (Sustenta) aimed to link small-scale farmers to commercial lead farmers and cooperatives and to finance business plans for small emerging commercial farmers (SECFs) and public extension agents to assist smallholder cooperatives. The World Bank also financed an irrigation project (Smallholder Irrigated Agriculture and Market Access Project; World Bank 2018f) to increase productivity through more efficient irrigation and to improve market access of production through enhanced business linkages between farmers and traders. A third project, the Northern Mozambique Rural Resilience Project, sought to improve access to opportunities for vulnerable communities and management of natural resources in selected rural areas of northern Mozambique. This was partly an emergency operation to assist internally displaced people affected by a hostile insurgency, but it also promoted growth and improved agricultural productivity using public extension agents to assist smallholder cooperatives. In addition, the project supported SECFs with grants to implement business plans for investments in priority value chains that benefit small-scale farmers.

The World Bank also supported increasing agricultural productivity through reforms to land rights, natural resource management, and rural roads. The Land Administration Project approved in 2018 was intended to increase land tenure security in selected districts and enhance the efficiency and accessibility of land administration services. An important element of this project’s design was decentralization of land administration to the community level and more rapid issuance of DUATs (Direito de Uso e Aproveitamento dos Terras)—that is, land use rights—to farmers. This change was expected to increase the ability of small-scale farmers to sell land-user rights and allow them to use DUATs as collateral to obtain credit to finance the adoption of technological changes that would increase productivity. Another area of investment was by IFC in a company producing avocados, in 2017 (€3.9 million) and 2019 ($2.8 million).

Several projects sought to reduce the substantial loss of forest areas each year as a result of slash-and-burn activities on small-scale farms. The Forest Investment Project aimed to reduce forest-area losses and increase agricultural and pastoral productivity (World Bank 2017c). The project sought to achieve these objectives by supporting geospatial capacity building for forest landscape development to ensure equitable and sustainable land use and by strengthening measures to adapt to and mitigate climate change. Until 2018, World Bank support for roads focused on the rehabilitation and maintenance of highways and their bridges along the important north-south transportation network. In 2018, the World Bank shifted focus from main roads and highways to selected rural areas by approving the Integrated Feeder Road Development Project. This project was intended to provide rehabilitation and maintenance on sections of secondary, tertiary, and vicinal (between towns) roads, as well as on some unclassified roads to enhance mobility in Zambezia and Nampula provinces to reduce transportation costs and facilitate farmers’ access to markets. The project is also expected to rehabilitate about 70 kilometers of primary roads to enhance connectivity to markets, ports, and other economic and social services. The scope of this project, however, is relatively small.3

The inclusion of gender in the World Bank’s agriculture productivity support became progressively more prominent over the years. At the beginning of the evaluation period, World Bank support included little gender targeting or explicit gender objectives. The only references to women related to educational inequality and maternal mortality. Gender targeting emerged in the CPS FY12–16. Specifically, objective 2 identified gender mainstreaming in land tenure and women’s micro enterprises as critical areas to support. In the latter part of the evaluation period, the World Bank incorporated gender in a more decisive and comprehensive manner. The SCD 2016 (World Bank 2016c), the CPF FY17–21 (World Bank 2017b), and the SCD update in 2021 dedicated space to gender in agriculture (World Bank 2021j), indicated priorities for addressing gender inequality to increase the impact of poverty reduction efforts, and focused on the need for attention to human capital development to increase the productivity of women in agriculture. The SCD update demonstrates the importance of women’s engagement in the design of agricultural extension programs. A change in the World Bank’s approach to gender targeting can also be observed with Gender Responsive Natural Resource and Landscape Management: A Mozambique Pilot Program (2020i); the Sustenta (FY16) and Estrela (FY16) projects, which contained results indicators for female beneficiaries; and the Northern Mozambique Rural Resilience Project (FY20), which included the involvement of women and girls as beneficiaries and stakeholders.

World Bank Effectiveness

Only two agricultural investment projects closed in the first half of the evaluation period, and neither performed well. Although beneficiaries in the Market-Led Smallholder Development in the Zambezi Valley Project achieved increased productivity, increases were substantially lower than those achieved by similar farmers not supported by the project (World Bank 2006). The quality of the project’s modest rural road construction and small bridges was low because of inappropriate design and insufficient maintenance. An impact evaluation of the extension program supporting improved land management found that there was a statistically insignificant impact on farmers’ adoption of sustainable land management techniques promoted by the project (Kondylis, Mueller, and Zhu 2014). A Project Performance Assessment Report for this project concluded that there were significant shortcomings in the project’s implementation and rated the overall outcome as moderately unsatisfactory (World Bank 2016b). An irrigation project saw the yield for major crops (rice and horticulture crops) increase, but cropping intensity in irrigation areas did not increase beyond one crop per year of rice, and new irrigation development fell short of the original target. IEG rated this project’s overall outcome as moderately unsatisfactory because of significant shortcomings in the achievement of objectives and modest efficiency (World Bank 2019b).

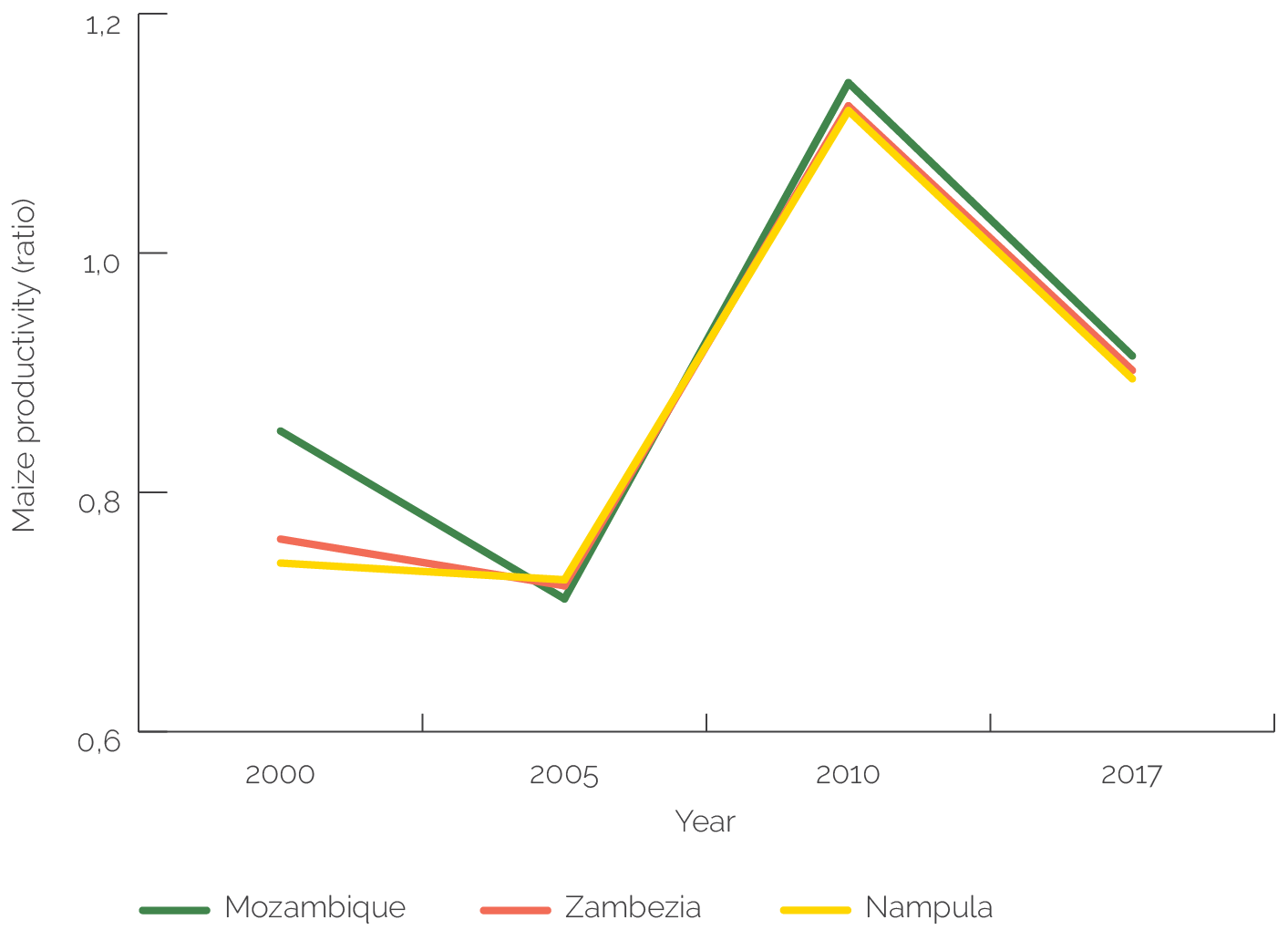

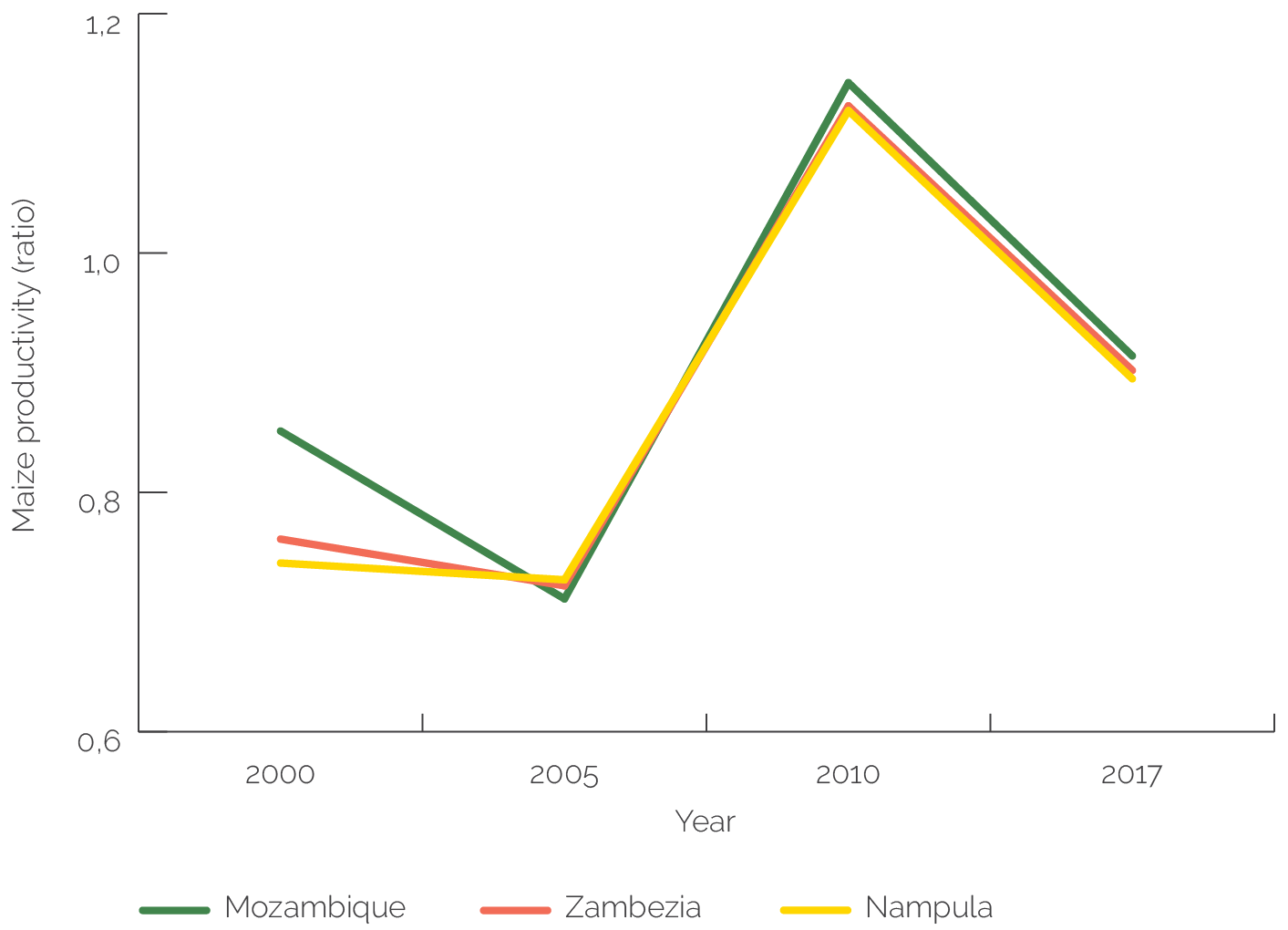

Agricultural productivity in provinces where World Bank projects were implemented since the start of the evaluation period does not show significant improvement compared with the average for Mozambique overall. The World Bank supported agricultural productivity in Nampula and Zambezia. These provinces produce almost one-quarter of all maize in Mozambique and represent almost 40 percent of the total population. Results show that the change in productivity in these supported provinces was similar to the change in the rest of the country (figure 3.2).4

Figure 3.2. Maize Productivity in Nampula, Zambezia, and Mozambique, 2000–17

Source: Independent Evaluation Group calculations based on International Food Policy Research Institute data.

Note: Productivity = production/area.

Early indications suggest positive outcomes for agricultural productivity due to greater attention to market access. Sustenta, whose core design is establishing and maintaining a network of 200 SECFs, supports improved technological know-how for small-scale traditional farmers. Bilateral donors piloted this SECF model in a range of provinces in Mozambique since 2009. Early indications are that Sustenta has made progress in building linkages between SECFs (lead farmers) and small-scale traditional farmers by meeting targets on developing value chains, maintaining rural roads, reforesting project areas, and promoting technology use by farmers. The design of this model benefited from lessons learned in other countries on comparable approaches, such as the case of nucleus estates, outgrower schemes, and lead farmer models in Ghana, Malawi, and Tanzania (Paglietti and Sabrie 2012; Stringfellow 1996). The Mozambican design also incorporated lessons on the essential role of extension services by ensuring that training and advice to small-scale farmers will be provided by SECFs and public extension services. In interviews for this evaluation, national agricultural development experts praised Sustenta’s project design as a major improvement over the World Bank’s previous agricultural development projects. Beneficiaries have also voiced strong support for agroforestry enterprises as alternatives to deforestation in the World Bank–financed Forest Investment Project. An important and successful feature of this project has been a detailed arrangement, designed and approved by stakeholders, to equitably distribute Carbon Fund payments to program participants.

Market development of the agriculture sector in Mozambique requires support to its institutional setup. The agricultural sector is burdened by weak institutional capacity to facilitate business activities and numerous regulatory barriers that increase the cost of doing business. Major improvements are required in agricultural research and extension institutions to provide the basis for the adoption of new technologies in Mozambique’s wide range of agro-climatic zones. Institutions that support microcredit will be necessary to finance small-scale farmers’ purchase of inputs associated with improved technologies such as seed and fertilizer. Lastly, institutions that can facilitate greater efficiency, such as weather forecasting and market information through radio and the internet, would benefit small-scale farmers and the employment prospects for unskilled workers from the agricultural sector.

A review of the lessons identified in evaluations of agricultural projects in Mozambique shows good learning from experience. Implementation Completion and Results Report Reviews and aide-mémoire in the first strategy period identified several important lessons related to agriculture and fisheries. These lessons included the need to examine (and support) local government capacity at the outset of the project in decentralized projects, the importance of flexible arrangements and longtime horizons of projects to build strong decentralization capacity, and the need for clear targeting and appropriate linkages for community empowerment. Time is reported as more important than money in sensitizing communities to issues of sustainability. For this reason, local presence, dedicated staff, and regular agriculture extension visits were considered critical to implementing agricultural projects in Mozambique. Many of these lessons were reflected in the following projects in the second strategy period. For example, the First Agriculture Development Policy Operation rightly identified the need to build both administrative and technical capacity of institutions that implemented reforms. Similarly, the Smallholder Irrigated Agriculture and Market Access Project incorporated lessons from the MZ PROIRRI Sustainable Irrigation Development Project (World Bank 2018f). Fisheries projects incorporated earlier lessons such as the need for a long horizon to complete reforms, a phased and consultative approach with local communities, and a strong implementation plan. The Mozambique Land Administration Project (Terra Segura) benefited from lessons set out in a World Bank Policy Note (Community Land Delimitation and Local Development; World Bank 2010a), such as the need for a more proactive, systematic, and clearly targeted program of community land delimitation. Finally, the design of the Sustenta project was based on relevant lessons drawn from, among other places, the 2016 SCD and the latest CPF, and the Northern Mozambique Rural Resilience Project drew lessons from Sustenta.

- See the following analyses: Higher Fuel and Food Prices (FY09); Infrastructure Corridors, Growth, and Welfare: Comparative Study of the Corridors of Beira and Nacala, Africa (FY09); Community Land Delimitation and Local Development (FY11); Poly Note: Rural Land Taxation in Mozambique (FY11); Analysis of Public Expenditure in Agriculture (FY12); and Mozambique Agricultural Sector Risk Assessment (FY15).

- A similar conclusion had been drawn in Mozambique—Beating the Odds: Sustaining Inclusion in a Growing Economy (World Bank 2008), but it did not influence the operational strategy until 2016.

- According to the program document, the classified road network—primary, secondary, tertiary, and vicinal—is 30,464 kilometers, 24 percent of it paved. This is equivalent to a road density of 2.9 kilometers per 100 square kilometers of land, which is relatively low compared with neighboring countries such as Kenya (10.8 kilometers per 100 square kilometers) and Tanzania (5.5 kilometers per 100 square kilometers).

- Nampula and Zambezia were the provinces receiving significant support from the World Bank. Although this analysis assumes that the volume of World Bank investments is sufficiently large to influence provincial changes in productivity, these results nevertheless confirm the micro-level results in the previous paragraph.