World Bank Group Support to Demand-Side Energy Efficiency

Chapter 3 | Coherence of World Bank Group Interventions to Support Scale-Up

Highlights

“Coherence”—the extent to which the World Bank Group supports complementary approaches to scaling demand-side energy efficiency (DSEE)—can be assessed internally (among the World Bank, the International Finance Corporation [IFC], and the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency) and externally (between the Bank Group and other actors).

World Bank DSEE approaches have been internally coherent in supporting vertical but not horizontal scale-up. The World Bank has been externally coherent in onlending with cofinanciers but less coherent on advisory support to clients and knowledge diffusion goals with client governments and partners. The external coherence of the World Bank Energy and Extractives Global Practice and Energy Sector Management Assistance Program in Vietnam is a best practice.

IFC DSEE approaches have been internally coherent for not only vertical but also horizontal scaling. IFC has supported horizontal scaling through blended finance programs and multicountry and multisector approaches. IFC has also been externally coherent in using its Excellence in Design for Greater Efficiencies certification to advance DSEE priorities with its client groups in the buildings sector and in supporting client governments that aim to address climate change and energy shortages.

The unwinding of the World Bank’s DSEE community of practice has limited collaboration on DSEE across sectors. The IFC Climate Business team has been critical to enabling IFC’s coherence across sectors in DSEE approaches.

Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency DSEE approaches have been internally coherent. Its DSEE clients (from industrialized countries) have been well positioned to embrace either the IFC Excellence in Design for Greater Efficiencies standard and related tool kits or the US Green Building Council Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design standard. The Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency has been externally coherent, partnering with the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development to provide political risk insurance for client priorities such as health care buildings in Türkiye and adopting external green building standards.

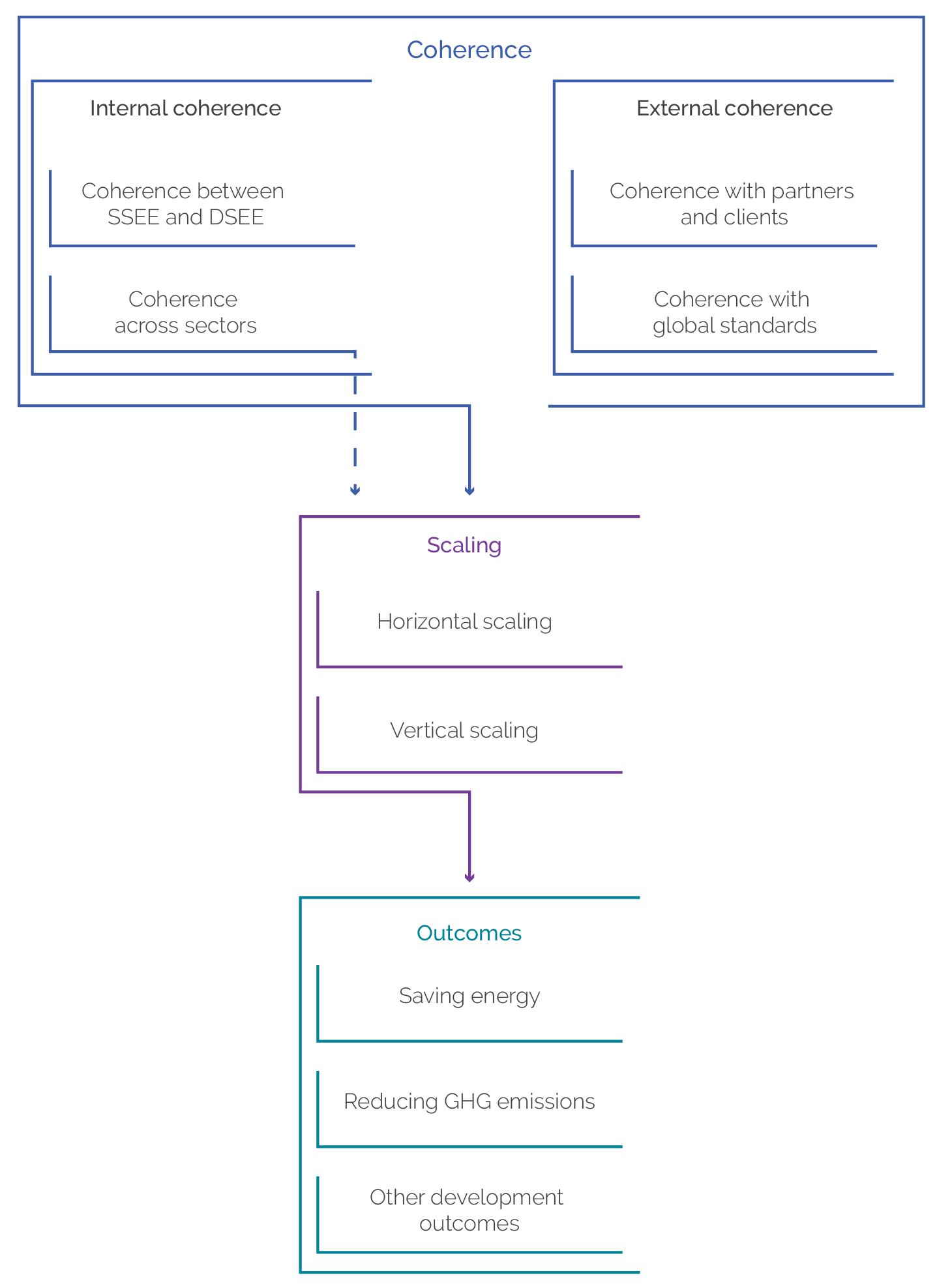

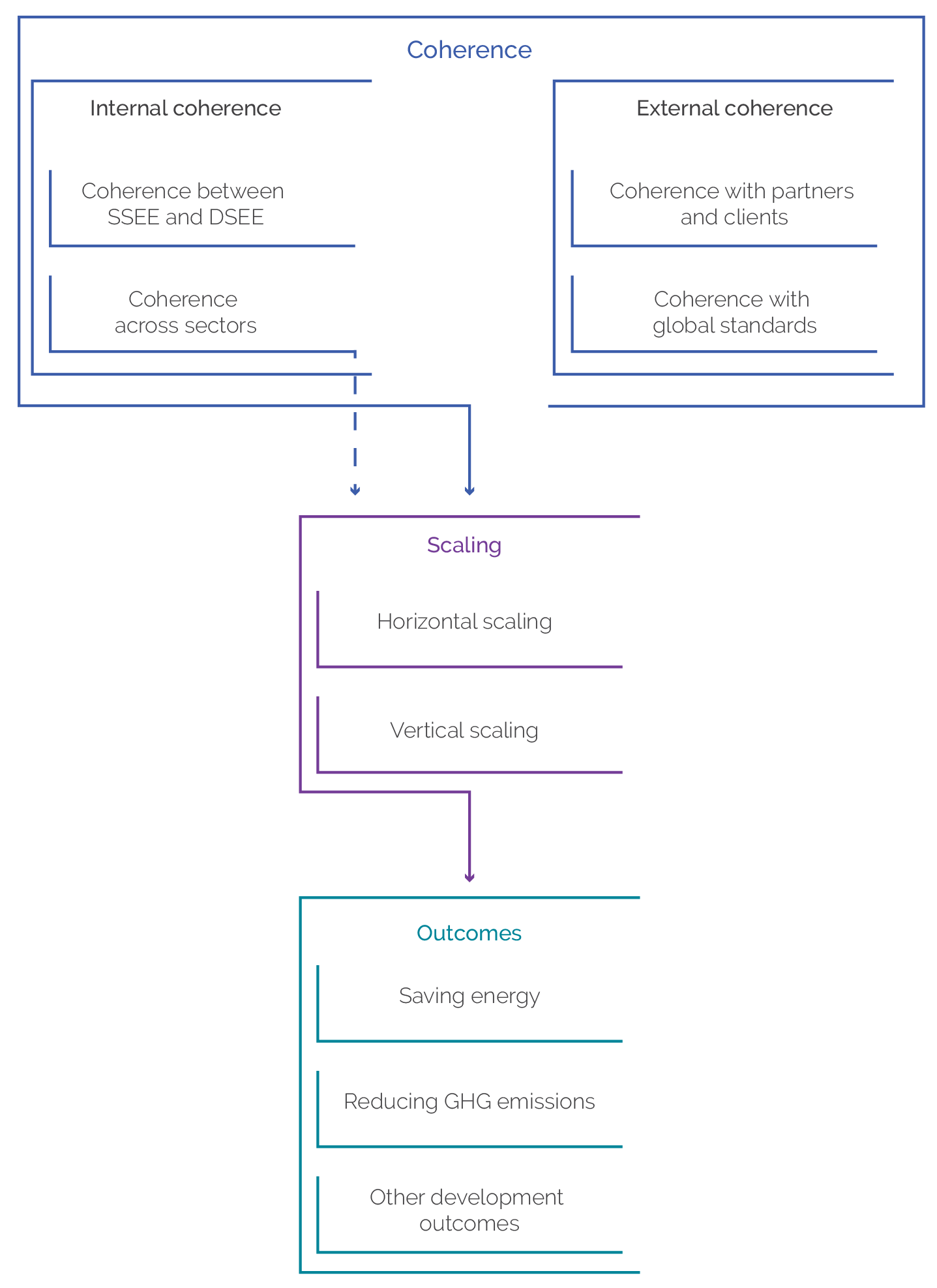

Coherence refers to the extent to which Bank Group DSEE interventions support or undermine each other and the interventions of Bank Group partners in reaching SDG 13, SDG 7, and Paris Agreement alignment.1 Achieving the desired long-term outcomes of DSEE—reducing energy use and GHG emissions—requires scaling. Scaling, in turn, requires coherence because incoherent approaches cannot, by themselves, achieve the scale needed for Paris Agreement alignment and meeting SDG 13 and SDG 7 targets. Only by working consistently in alignment internally and with external partners can the Bank Group hope to reach the scale that is necessary to have an impact.

Coherence has several aspects. Coherence can be internal (within the Bank Group) or external (between the Bank Group and other actors). In this report, internal coherence refers to (i) the complementarity of Bank Group support for addressing clients’ SSEE needs (such as utility upgrades and reforms) and support for addressing DSEE needs and (ii) the complementarity of interventions across sectors (including the complementarity of World Bank interventions across the GPs and of IFC interventions across industry groups). External coherence refers to (i) the complementarity of Bank Group interventions with those of client governments and partner development institutions and (ii) the alignment of Bank Group interventions with international standards. Evidence of coherence includes coordination, joint initiatives, cofinancing, consistency, avoidance of duplication, synergies among interventions, and alignment with international standards.

All aspects of coherence are important, but one stands out as particularly important: internal coherence across sectors, meaning that the Bank Group aligns its DSEE approaches in different sectors. Internal coherence across sectors is fundamental because horizontal scaling implies, by definition, scaling across multiple sectors. Therefore, coherence across sectors contributes directly to horizontal scaling (dashed arrow in figure 3.1). Horizontal scaling is essential for reducing energy use (SDG 7) and GHG emissions (SDG 13 and Paris Agreement alignment) at scale, yet it has been elusive in the portfolio.

Figure 3.1. The Relationship among Coherence, Scaling, and Outcomes

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: DSEE = demand-side energy efficiency; GHG = greenhouse gas; SSEE = supply-side energy efficiency.

Internal Coherence

Coherence between Supply-Side and Demand-Side Energy Efficiency

A minority of World Bank energy efficiency interventions had coherent SSEE and DSEE elements. Of a sample of 231 World Bank lending projects with SSEE, 25 percent (58 projects) had DSEE elements. For example, the $72 million credit to Malawi via the Energy Sector Support Project (P099626; 2015–18) aimed to increase the reliability and quality of electricity supply in the country and supported complementary SSEE and DSEE interventions. The SSEE interventions included rehabilitating underground transmission cables to reduce the amount of electricity lost because of inadequate insulation. The DSEE interventions (3 percent of the total project cost) included installing automated meter readers that allowed large commercial customers to better monitor and manage their energy consumption while allowing the utility a real-time (remote) monitoring of meter performance on customer sites to better detect losses due to theft. The cable rehabilitation, automated meter readers, and other activities that the project supported reduced electricity losses per year from 25 percent to 17 percent. Reducing losses increases energy efficiency because overcoming losses requires generating excess energy to meet end-user demand. (See Naeher, Narayanan, and Ziulu 2021 for more information about this project.)

The World Bank has taken various approaches to coherently addressing SSEE and DSEE needs. In addition to the approaches taken in the Malawi project, the World Bank has supported coherent supply- and demand-side interventions using smart metering (for example, in Burkina Faso and Poland), time-of-use pricing, and energy demand–based pricing for large consumers (for example, in Rwanda and Vietnam).2 These mechanisms are both supply-side and demand-side interventions because they provide information to utilities (supply) and consumers (demand) to maintain supply-demand equilibrium. Doing so promotes both system reliability and energy efficiency. For example, time-of-use pricing is a demand-response technique that adjusts the price of electricity based on when it is used. During hours of typically high demand, the cost of using electricity is higher, reflecting the cost of supplying electricity at that time. The price signal reduces electricity demand when supply is tight. The practice benefits both suppliers and consumers (for example, by improving system reliability and thus avoiding blackouts) in addition to increasing energy efficiency (Eid et al. 2016). Although limited in number (four projects), these interventions have increased access to and reliability of electricity by reducing peak load while simultaneously improving energy conservation by inducing people and firms to use less energy.3

Coherence across Sectors

World Bank DSEE interventions had limited coherence across the energy, water, agriculture, and transport sectors. In principle, many World Bank GPs, not only the Energy and Extractives GP, could address DSEE. However, in practice, GPs outside of Energy and Extractives have made limited contributions to DSEE. For example, the Transport GP was responsible for only 6 percent of total World Bank DSEE commitments ($0.8 billion in 4 projects over 10 years) and the Water GP for only 5 percent. In the water sector, a small share of energy efficiency interventions (18 projects with $500 million in lending commitments over 10 years) included upgrading and modernizing water treatment plants and pumping stations to help reduce energy costs and contribute to GHG emission reduction.

DSEE requires coherence in design, measures, and actions between the energy sector and other sectors to achieve parallel reforms and manage spillover effects. The Jordan First and Second Programmatic Energy and Water Sector Reforms development policy loans (2015–18) are a good example of a programmatic intervention designed to coherently address the water-energy nexus for horizontal scale-up. Jordan is among the countries most affected by water scarcity, and its energy and water sectors are highly interdependent. Energy use for water pumping and treatment accounts for half of the costs in the water sector, which uses 15 percent of Jordan’s total electricity generation and is the largest energy consumer. Consequently, policy and operational changes in one sector directly affect the other, requiring careful coordination among them. As the government aimed at cost recovery through tariff increases in both the energy and water sectors, the DPOs supported the government of Jordan in reducing inefficiencies in the water sector, particularly those related to energy use. The projects involved a combination of energy cost-reduction measures, including through energy efficiency in pumping operations, the improvement of water supply systems to reduce physical losses and energy input, and the use of renewable energy. This helped increase energy savings (achieved 84 gigawatt hours versus the target of 50 gigawatt hours) in the water sector by 2017, beyond the targets set by the Ministry of Water and Irrigation (World Bank 2019b). However, steep increases in electricity tariffs by the National Electric Power Company and charged to the Water Authority of Jordan since 2018 outpaced any energy efficiency gains achieved earlier without corresponding increases in water tariffs by the Water Authority of Jordan, diminishing the effectiveness of the parallel reforms. Furthermore, a lack of continuous World Bank engagement and cumulative investments limited spillover effects from the energy sector to other sectors, including water. The water sector in Jordan still struggles with the heavy burden of an average 24 percent increase in electricity tariffs since 2013 and from the additional pressure of hosting 1.3 million Syrian refugees (IMF 2022).

Transport interventions especially need to aim at increasing energy efficiency. The transport sector was responsible for approximately 27 percent of total energy-related GHG emissions in 2019 (IEA 2021b), and there are enormous unexploited mitigation potentials from energy efficiency in transport. However, the Transport GP did little on energy or fuel efficiency during the evaluation period. Measures to improve vehicles, fuels, and energy efficiency in transport facilities constituted only a fraction of the transport sector interventions. Moreover, typical interventions (such as the modernization of bus fleets) did not measure fuel efficiency. World Bank transport projects also did not explore digital services that could contribute to transport decarbonization (such as intelligent transport management that includes, for example, route optimization and shipping programming; Dominioni and Englert 2022). Designing transport projects to demonstrate energy efficiency and climate co-benefits would help scale DSEE, including by mobilizing green finance and demonstrating climate abatement opportunities to developers.

The World Bank’s DSEE community of practice and DSEE solutions group have been dormant in recent years, limiting collaboration on DSEE across sectors. During the first half of the evaluation period, the World Bank’s DSEE community of practice—which included representatives of the Energy and Extractives GP and the Climate Change Global Solutions Group of the Sustainable Development Practice Group—coordinated efforts with ESMAP. Together, they created a coherent blended DSEE approach, combining GCF commitments and World Bank lending for a new sustainable cooling initiative that cut across the energy and transport sectors. (It supported, for example, improvements in the efficiency of refrigeration services in both buildings and trucks.) Such forward-looking initiatives led to identifying cooling-related projects (such as cold chain logistics and warehousing)4 in Bangladesh, North Macedonia, Panama, and Sri Lanka. The approaches also led to innovative analytical work, such as The Cold Road to Paris (World Bank 2021a), needs assessment in food safety, and health sector interventions that require cooling solutions for food and vaccine transport. However, because the community of practice has been dormant in recent years, the World Bank has lacked an alternative centralized group or mechanism to facilitate the coherence of DSEE interventions across sectors. The inactivity of the community of practice and a limited focus on emerging DSEE issues have constrained cross–Practice Group collaboration and integrated approaches to DSEE projects.

IFC’s approach to DSEE has been coherent across diverse sectors (industry groups and business lines). IFC has mainstreamed DSEE investment projects across three industry groups: the Financial Institutions Group; Infrastructure and Natural Resources; and Manufacturing, Agribusiness, and Services (figure 3.2, panel a). Similarly, IFC advisory services mainstreamed DSEE across all its business lines (figure 3.2, panel b). During the second half of the evaluation period, Manufacturing, Agribusiness, and Services took the lead on DSEE in IFC investment services ($1.9 billion for FY16–20), driven by increased demand for green buildings. In the recent two-year period, Infrastructure and Natural Resources has been building its pipeline on DSEE by targeting publicly owned and private airports and developing opportunities for green public infrastructure. IFC’s Partnership for Cleaner Textile program is a good example of a coherent water and energy efficiency approach. Partnership for Cleaner Textile is a horizontally scalable program that supports the entire textile value chain—spinning, weaving, wet processing, and garment production—in adopting cleaner production practices.5 The program engages with technology suppliers, industrial associations, financial institutions, and governments to bring about systemic and positive environmental change for the Bangladesh textile sector and contribute to the sector’s long-term competitiveness and environmental sustainability.

Figure 3.2. International Finance Corporation Demand-Side Energy Efficiency Support

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: CDF = Disruptive Technologies and Funds; FIG = Financial Institutions Group; FY = fiscal year; IFC = International Finance Corporation; INR = Infrastructure and Natural Resources; MAS = Manufacturing, Agribusiness, and Services.

IFC has used blended finance to improve coherence on DSEE across sectors. Combining concessional loans with commercial loans for DSEE addresses several priorities and barriers at once: targeting critical economic actors operating in different sectors (for example, small and medium enterprises); providing financial instruments that are popular in one or more sectors (for example, leasing for small and medium enterprises operating in the energy, agriculture, and service sectors); removing barriers for domestic DSEE adoption (for example, by providing long-term financing in local financial markets where it is absent or limited); and targeting energy-intensive client firms (such as big importers of fuels). IFC’s successful blended finance model for DSEE in Türkiye is an example (box 3.1).

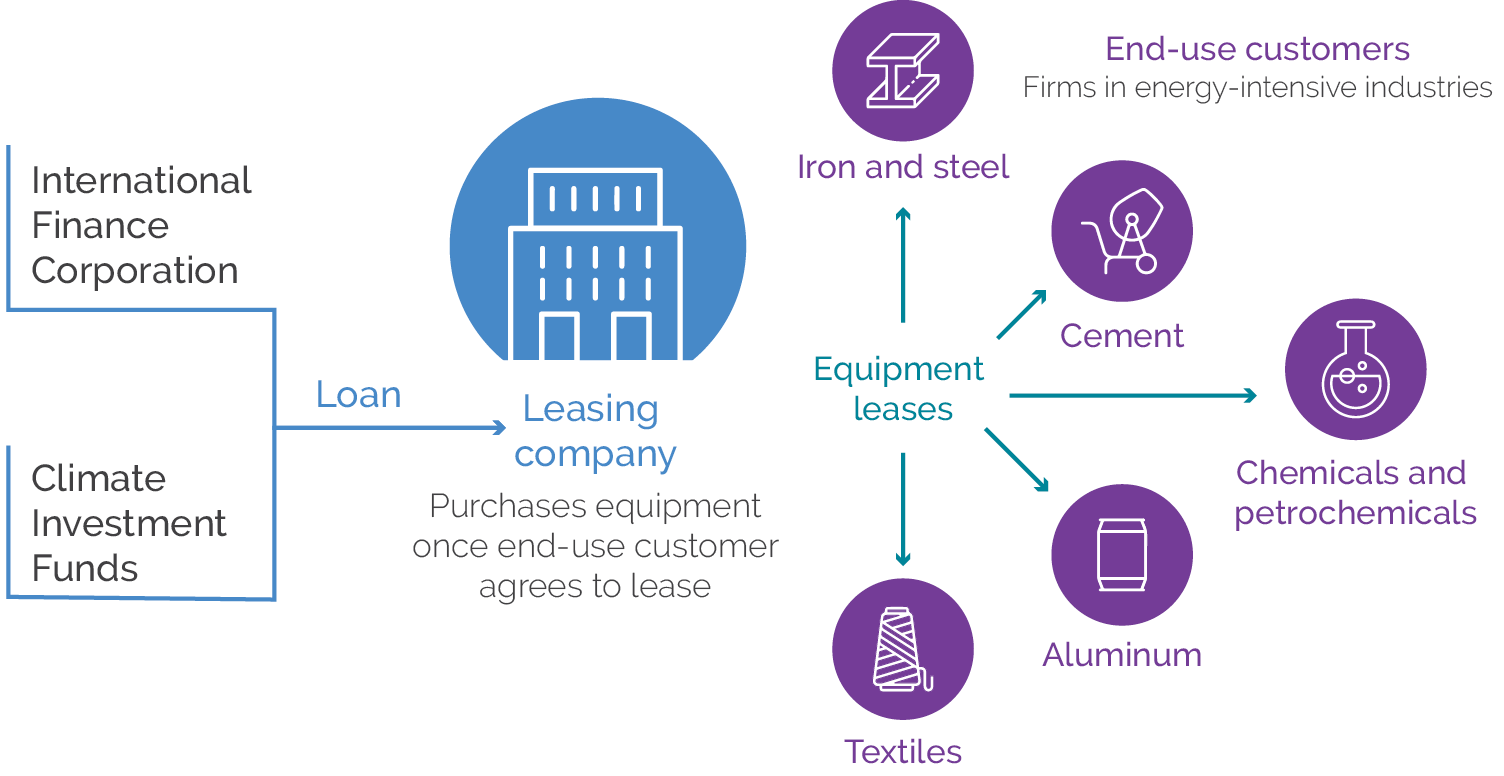

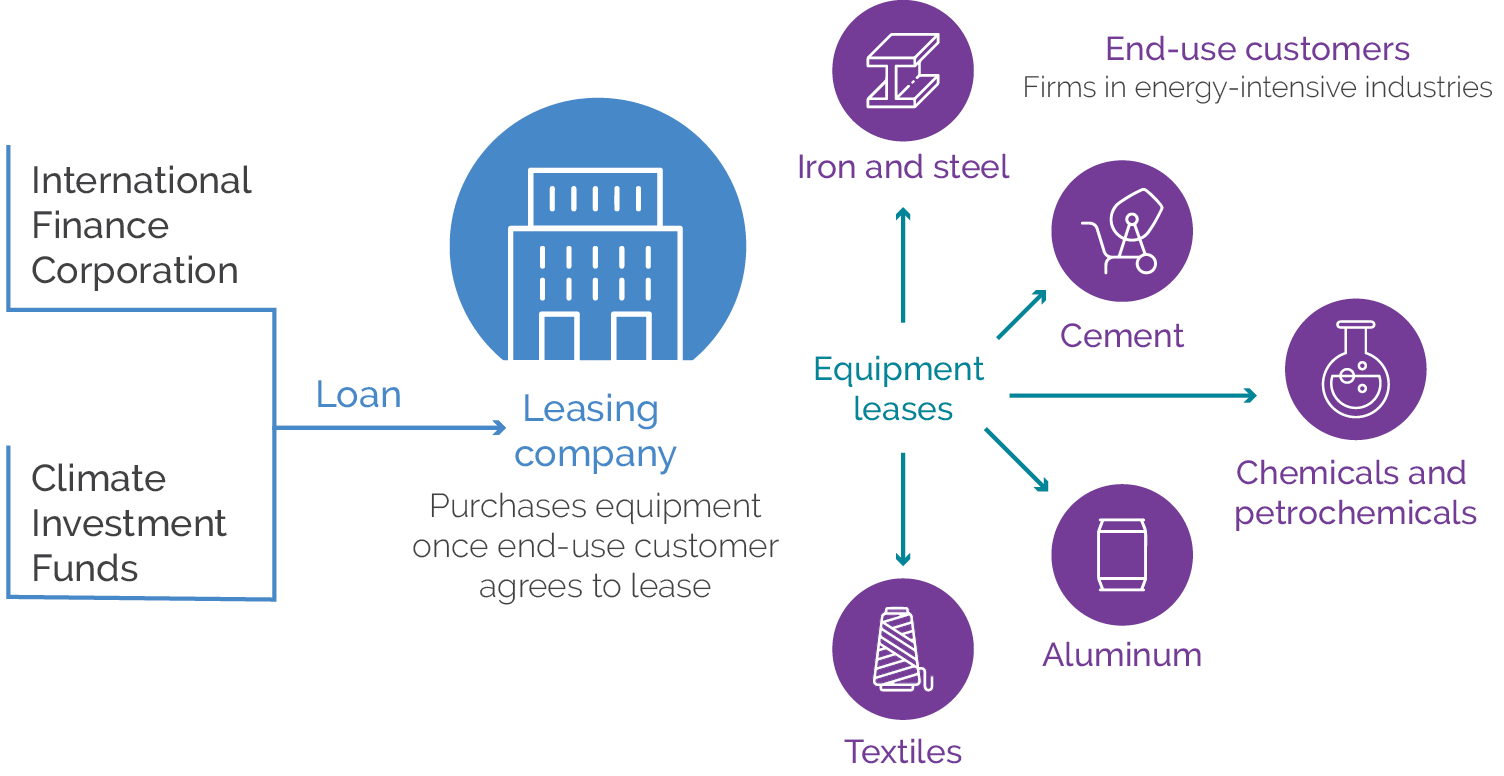

Box 3.1. Blended Finance to Support Demand-Side Energy Efficiency across Sectors

The International Finance Corporation (IFC) Commercializing Sustainable Energy Finance program in Türkiye coherently focused on multiple energy-intensive sectors, such as textile manufacturing and metal production, by increasing demand-side energy efficiency financing through local commercial banks. IFC financed the program with roughly US$21 million from the Clean Technology Fund (a World Bank–administered financial intermediary fund) blended with almost US$100 million of IFC’s own funds. IFC developed a leasing model for demand-side energy efficiency (figure B.3.1.1), which was nonexistent in Türkiye. IFC provided blended concessional loans to three Turkish leasing companies. The leasing companies, in turn, provided leases to firms operating in energy-intensive industries that wanted to finance demand-side energy efficiency projects and industrial equipment that met specific energy efficiency parameters (for example, reducing energy consumption by at least 15 percent). Once a customer decided to acquire energy-efficient equipment, one of the leasing companies would purchase the equipment using Commercializing Sustainable Energy Finance funds and provide the equipment through a lease to the customer. In 2015, IFC reduced its concessions to local banks and began lending on commercial terms because the market had transformed. The use of blended finance enabled a leasing model that allowed companies in several industries to improve energy efficiency, planting the seed for horizontal scale-up. The ensuing market transformation (local banks lending on commercial terms) reinforced the potential for scale-up.

Figure B.3.1.1 International Finance Corporation Blended Finance Approach to Demand-Side Energy Efficiency

Sources: Clean Technology Fund, https://www.climateinvestmentfunds.org/topics/clean-technologies; Independent Evaluation Group.

Some of IFC’s recent DSEE approaches specifically aim for coherence across sectors. Over the past three years, IFC’s DSEE approaches have evolved beyond targeting the energy efficiency of individual firms’ buildings to coherently targeting energy efficiency across supply chains of energy-intensive industries. For example, EDGE certified 49 stores of a retail food chain in an Eastern European country.6 IFC and the chain’s parent company have since discussed greening all of its more than 100 stores and other assets globally, including the logistics fleet. Doing so would involve greening cooling solutions in cold supply chains (for meat, for example) and storing goods in warehouses that use green building materials, minimizing heating and cooling needs, and taking advantage of natural lighting. Because this approach incorporates the transport and logistics sectors in a retail chain (or backward linkages),7 it is a promising example of coherence across sectors, even though it is too early to assess whether it will be effective. Another example of coherence across sectors is IFC’s support to an Argentina-based firm in the limestone industry. The IFC project aimed to implement energy efficiency measures to reduce the GHG emissions and embodied carbon of the limestone firm and firms in related industries. The project included support for the client to transfer its know-how and technology about improving energy and water efficiency to firms in other industries—such as mining and steel production—that could contribute to reducing the GHG emissions of the client’s buildings.

The IFC Climate Business team demonstrates that a centralized unit that supports coordination across sectors is critical for the coherence of DSEE interventions. IFC approached DSEE using a climate lens during the evaluation period, channeling most of its DSEE investments through the IFC Climate Business team as the central coordinating unit across IFC industry groups. The industry groups originate deals, and the Climate Business team, together with industry specialists and advisory teams, provides the groups with knowledge, technical, and industry specialist support. The Climate Business team also provides the industry groups with input on clients’ needs and collects feedback on global DSEE standards from industry actors and Bank Group colleagues. The Disruptive Technologies and Funds industry group initiated the IFC TechEmerge program in close collaboration with the Climate Business team and industry teams to provide concessional and grant funding to pilot projects across sectors. Examples include pilots for temperature-controlled logistics firms (the transport sector), cooling technologies in supermarkets (the retail sector), and resource efficiency and cooling solutions for hotels (the hospitality sector).

MIGA applies a coherent approach to green building standards in its projects. MIGA DSEE clients (from industrialized countries) have been well positioned to embrace either the LEED or EDGE global standards for buildings, the latter of which is a standard advocated by IFC. In the hospitality-cluster project, where IFC and MIGA are partnering across some of the subprojects (individual hotels), MIGA and IFC are jointly supporting the client’s adoption of the EDGE certification standard.

External Coherence

Coherence with Partners and Clients

MDBs as a group do not have a coherent approach to DSEE. MDBs, including the Bank Group, are incoherent in linking DSEE interventions to the primary DSEE development outcomes of saving energy and reducing GHG emissions. In addition, most MDBs do not have a unified approach to advancing DSEE standards. For example, the industrial and building segments have multiple national and international green building standards around the world in addition to EDGE: the US Green Building Council’s LEED, the UK government’s Building Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Method, and national standards, such as Building Energy Performance—Türkiye. The MDBs (including the Bank Group) do not have coherent approaches to advancing DSEE standards and deploy different standards for different interventions.

MDBs, including the Bank Group, are also incoherent in linking DSEE approaches to more comprehensive socioeconomic benefits and communicating the benefits of DSEE to stakeholders. Table 3.1 shows how the major MDBs approach central aspects of DSEE. Most consider DSEE a key priority. Some have cross-sectoral approaches and results frameworks for DSEE interventions. However, none track the socioeconomic benefits of DSEE interventions (related to health or gender, for example) or have a clear communication strategy to catalyze end-user adoption of DSEE at scale. In this incoherent environment, it is impossible for the Bank Group to consistently support interventions that complement those of partner development institutions and other multilateral actors. Yet, the Bank Group has missed opportunities to exhibit leadership in coordinating with other MDBs to increase external coherence in DSEE by, for example, setting green standards for public infrastructure, establishing precedents for using SOEs as project implementation units, improving links to DSEE co-benefits, and communicating benefits clearly to end users. The recently prepared joint MDB assessment framework for Paris Alignment (2022), which aims at collaborative work toward low-emission and climate-resilient development, is a step in the right direction.

Table 3.1. Multilateral Organizations’ Approaches to Demand-Side Energy Efficiency

|

Criterion |

ADB |

AfDB |

AIIB |

EBRD |

IDB |

IsDB |

World Bank Group |

|

DSEE key priority |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

— |

Y |

|

Results framework for DSEE interventions |

Y |

Y |

Y |

— |

— |

Y |

Y |

|

Socioeconomic links |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

|

Cross-sectoral approaches |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

— |

— |

|

Communication strategy on DSEE |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: Analysis is based on desk reviews of annual reports, MDB energy sector strategies, select country program documents of MDBs, and key informant interviews. — = no; ADB = Asian Development Bank; AfDB = African Development Bank; AIIB = Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank; DSEE = demand-side energy efficiency; EBRD = European Bank for Reconstruction and Development; IDB = Inter-American Development Bank; IsDB = Islamic Development Bank; MDB = multilateral development bank; Y = yes.

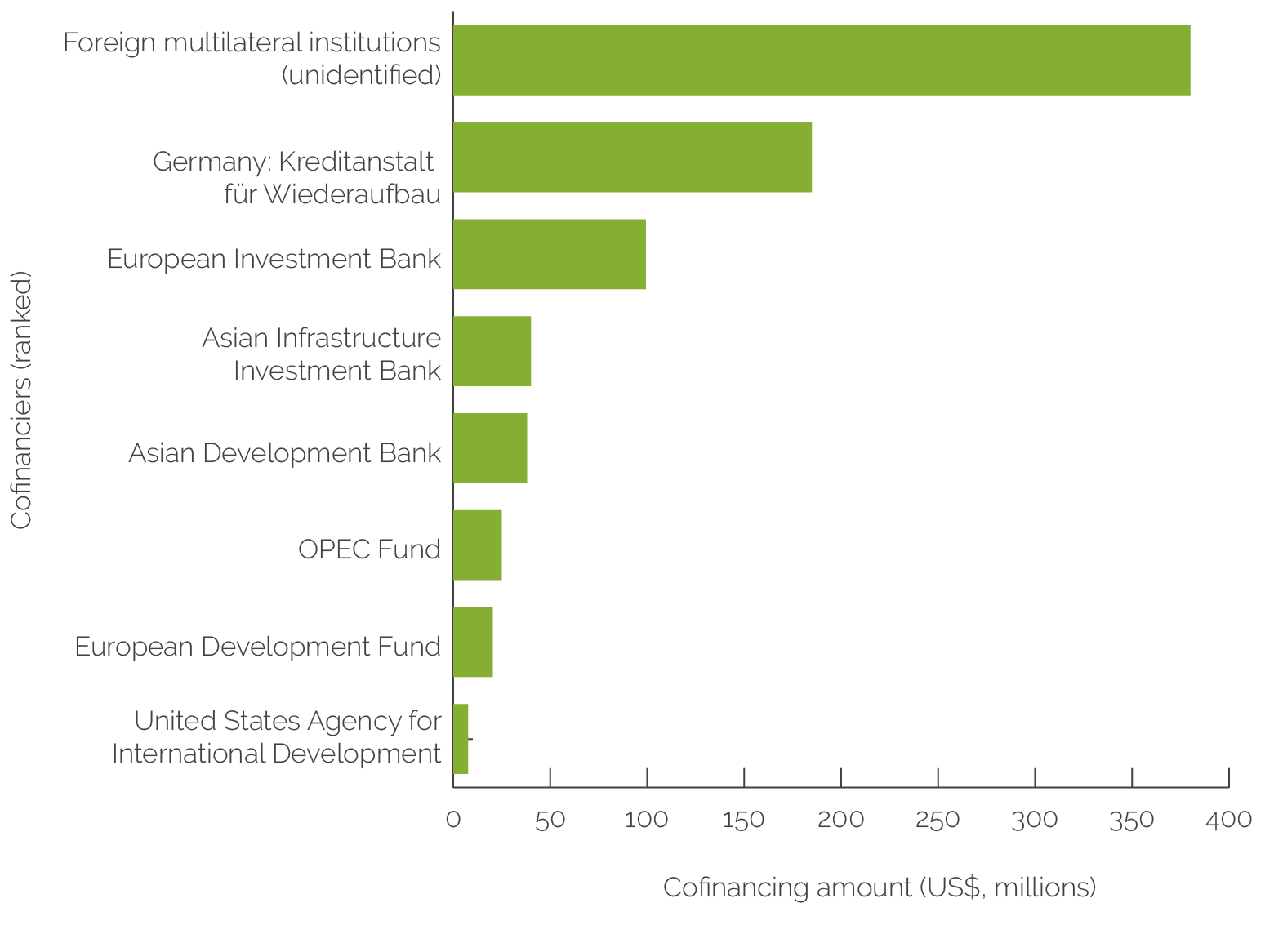

The Bank Group has been externally coherent with cofinanciers. The Bank Group has crowded in various funding sources (including MDBs, other development finance institutions,8 and donors) for DSEE lending, illustrating its coherence with these cofinanciers (figure 3.3). The amount of trust fund financing supporting World Bank lending for DSEE grew in the second half of the evaluation period through cofinancing arrangements with the CTF, the Global Infrastructure Facility, the GCF, and the ESMAP.

However, the World Bank has been less coherent on advisory support to clients and knowledge diffusion goals with clients and partners. World Bank ASA and ESMAP support (which focus on World Bank lending) have limited coherence related to crowding in global knowledge (for example, on Paris Agreement alignment needs or Net Zero Consortium efforts) and limited alignment with green standards and global consortiums. Recent World Bank research on green maritime transport (Englert et al. 2021) is promising.9

Figure 3.3. Demand-Side Energy Efficiency Cofinanciers by Commitment for Investment Project Finance, 2011–20

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: OPEC = Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries.

External coherence is important for greening public infrastructure at scale. The World Bank is ideally placed to decarbonize public infrastructure (including public buildings) as part of pursuing the two primary DSEE outcomes (GHG emissions reduction and energy-use savings). However, it can only do so if its actions are externally coherent. Reducing energy use in publicly owned buildings (such as schools and hospitals) requires building external coherence with cofinanciers (such as GEF and CTF) and eventually local financial institutions. A World Bank project in Armenia illustrates the point: it partially achieved the greening of public infrastructure, but it could have achieved more by improving external coherence with other partners (box 3.2).

Box 3.2. The World Bank’s Support for Demand-Side Energy Efficiency in Armenia

The World Bank Energy Efficiency Project in Armenia (2011) financed energy efficiency upgrades to eligible public and social buildings to reduce energy consumption. A World Bank–administered Global Environment Facility grant of US$1.82 million financed the project to demonstrate a replicable and sustainable model for energy efficiency investments in Armenia’s public sector with cofinancing from the implementing agency, the Renewable Resources and Energy Efficiency Fund. This fund was set up under a previous World Bank project (2005) as a nonprofit organization to promote renewable energy and energy efficiency. In this project, the fund acted as the implementation agency and channeled the World Bank and Global Environment Facility lending to demand-side energy efficiency (DSEE) using energy performance contracts. This approach of using a state-operated fund as an implementation agency to cofinance and deliver DSEE aimed to increase awareness of the economic benefits of energy efficiency and stimulate demand for energy efficiency financing.

The 2011 DSEE project financed insulation of walls, basements, and attics; repair or replacement of external doors and windows; window optimization; reflective surfacing of walls behind radiators; improvements or replacement of boilers and heating systems; replacement of mercury vapor lamps with high-pressure sodium vapor lamps (or LEDs); and replacement of incandescent bulbs with compact fluorescent lamps. Investments in schools and universities, hospitals and medical centers, penitentiaries, street lighting, and theaters resulted in lifetime energy savings for the end users of about 540.2 gigawatt hours and a greenhouse gas emissions reduction of approximately 145 metric kilotons of carbon dioxide, exceeding the project’s targets.

Yet the project addressed only a small fraction of the country-level needs in greening the public sector in Armenia; the 124 public buildings upgraded through the project amount to only about 2 percent of more than 5,800 public buildings. Moreover, there were no spillover effects or continuity beyond the initial results. There was no concerted effort to build a more comprehensive network of cofinanciers, such as domestic financial institutions or development finance institutions willing to take on commercial risk or partner with donor organizations. Doing so would have required greater external coherence from the World Bank, working with development partners and the private sector to engage with the government of Armenia, identify the right project implementation unit, and catalyze DSEE investments at scale.

Source: World Bank 2019a.

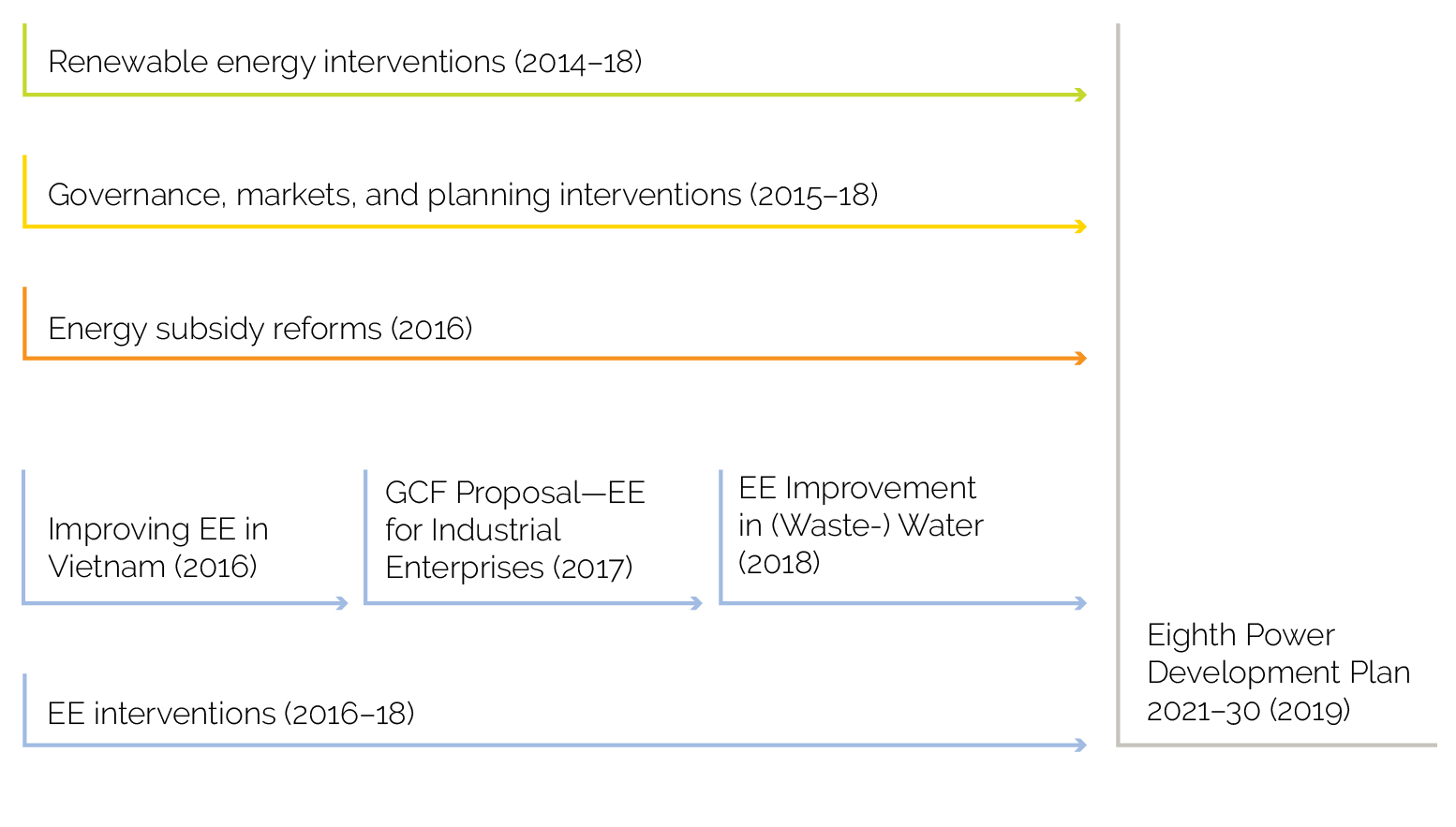

The external coherence of the World Bank Energy and Extractives GP and ESMAP in Vietnam can be a model for interventions in other industrializing countries. The World Bank’s ESMAP offers a unique pathway for collective action with cofinancing partners such as development finance institutions, governments, and agencies financing trust funds, including the GEF and the CTF. Coherent ESMAP technical assistance support was at the heart of the government of Vietnam’s energy planning, which included concurrent and sequential interventions on energy efficiency, energy subsidies, renewable energy, and governance (figure 3.4). Three factors were critical for success in Vietnam. The first was ESMAP’s status as a preferred partner on energy sector development. The second was coherent sequencing of ESMAP interventions, such as developing the overall government policy framework ( World Bank 2010b) before supporting scale-up in the industrial sector (GCF proposal on energy efficiency for industrial enterprises in 2017) and the real sector (energy efficiency improvement in wastewater in the Vietnam Scaling Up Energy Efficiency project, 2018). The third factor of success was aligning and linking activities across ESMAP’s cross-cutting programs. For example, ESMAP complemented efforts to reduce subsidies under its Energy Subsidy Reform Facility by using its Annual Block Grants program to finance a software model for assessing the impacts of such pricing changes. ESMAP’s coherence in Vietnam has contributed to substantial results: the government of Vietnam is promoting more aggressive energy efficiency targets; the 2019–30 energy savings program aims to reduce the total nationwide energy consumption by 8 to 10 percent, up to 2.5 exajoules (equal to approximately 78 times the daily electricity production of all the nuclear power plants in the world).

IFC’s DSEE approaches are coherent with the policies and strategies of select client governments that aim to address climate change and energy shortages. In Colombia, for example, IFC responded to a government request for support in reducing GHG emissions in the construction sector by promoting energy efficiency and water conservation in new buildings. In Indonesia, IFC aligned with the government policy in both its investment and advisory services to reduce GHG emissions from buildings through the enforcement of mandatory regulations. Between 2012 and 2015, the government passed 13 separate pieces of legislation promoting green buildings and supporting climate-smart investments. IFC’s DSEE approaches assisted with establishing green building codes using incentives (such as green mortgages and home insurance) to attract residential buyers and encourage private sector uptake (for example, by commercial and residential real-estate property developers). IFC addressed the government of South Africa’s issue of high peak loads and a need to reduce power consumption to stop frequent rolling blackouts by providing advisory services to facilitate the adoption of green building standards.

Figure 3.4. World Bank and Energy Sector Management Assistance Program Contributions to Vietnam’s Energy Planning

Source: ICF International 2020.

Note: EE = energy efficiency; GCF = Green Climate Fund.

Coherence with Global Standards

Mandating building standards via the construction sector, when the standards are formulated and aligned with global standards, continuously updated, and enforced, contributes to scaling DSEE. Mandating building energy efficiency standards (for example, building codes for roofing or windows) has proven to be effective in developed and industrialized countries by reducing energy use (IEA 2020a). Furthermore, an IEG literature review suggests that mandatory global standards can initiate a positive feedback loop of government-led enforcement, supply of technologies and materials from the private sector, development of compliance capacity at enforcement agencies, and alignment with investor expectations that is reinforced over time. Review of advisory and knowledge work suggests that the Bank Group has been coherent in advocating for global building standards in client countries.

The World Bank’s ESMAP and the Carbon Finance Unit have actively promoted global building standards and the benefits of enforcement since 2008 via advisory and knowledge work. The World Bank demonstrated coherence of its work with global DSEE standards in three different ways. First, through its knowledge products (for example, Mainstreaming Building Energy Efficiency Codes in Developing Countries [World Bank 2010a]), the World Bank evaluated and showcased global experiences with building standards, extracted good practices in implementing building standards, and developed a carbon finance methodology for supporting programs and projects that invest in creating more energy-efficient buildings. Second, through the promotion of the United Nations’ Clean Development Mechanism, the World Bank has further advocated for global building standards in the past decade. Finally, the World Bank ESMAP has advocated for IFC’s global certification and standard processes (via EDGE) in its advisory programs.

IFC is coherent with global DSEE standards with a singular focus on green buildings. IFC has been coherently using its EDGE certification and standards process to advance DSEE priorities with its client groups in the buildings sector. IFC uses the certification as an entry point to identify investment opportunities for greening buildings across subsectors in the six Bank Group Regions. IFC communicates consistently with its clients and partners and has prioritized EDGE standard adoption. In addition, EDGE is supported by several development partners, including the GEF and ESMAP.

MIGA has been externally coherent with other development partners and DSEE-related building standards. MIGA has exhibited external coherence in contributing to energy efficiency by supporting investments in green buildings for health care facilities and offices in Türkiye via cofinancing arrangements with the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development. For example, MIGA’s provision of political risk insurance for a European Bank for Reconstruction and Development bond in Türkiye boosted the bond’s rating; the improved rating increased the bond’s attractiveness to investors, mobilizing funding from international and local banks and institutional investors (Rosca 2016). Moreover, MIGA was coherent with external green building certifications. The five subprojects for the health sector in Türkiye obtained external green building certifications, including LEED and Building Energy Performance—Türkiye.

1 This evaluation uses the definition of coherence from the Development Assistance Committee Network on Development Evaluation of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (https://www.oecd.org/dac/evaluation/daccriteriaforevaluatingdevelopmentassistance.htm#coherence-block).).

2 Demand-based pricing is a demand-response technique that adds a surcharge to end-user utility bills based on their highest period of energy use in a month.

3 Peak load is the greatest amount of energy that consumers draw from the grid in a set period of time (for example, one day).

4 A cold chain is a low-temperature-controlled supply chain. An unbroken cold chain is an uninterrupted series of refrigerated production, storage, and distribution activities, along with associated equipment and logistics, which maintain quality via a desired low-temperature range.

5 Cleaner production means using resources, such as raw materials, electricity, and water, more efficiently to minimize waste.

6 Excellence in Design for Greater Efficiencies certifies buildings as “green,” meaning that they efficiently use resources, such as energy, water, and materials.

7 Backward linkages characterize the relationship of an industry or institution with its supply chain. An industry has significant backward linkages when its production of outputs requires substantial intermediate inputs from many other industries.

8 A development finance institution is any financial institution that provides risk capital on a noncommercial basis for economic development. A multilateral development bank is a financial institution created by a group of countries to provide financing and professional advice for enhancing international economic development. As such, a multilateral development bank is a type of development finance institution. Other types of development finance institutions include national development banks, community development banks, and certain microfinance institutions, among others.

9 The World Bank has commissioned an external consultant and academics (UMAS: University Maritime Advisory Services) to study the potential for green bunker fuels, such as ammonia and hydrogen, and to promote decarbonization in the shipping and maritime industry. The second volume of the study will focus on liquefied natural gas as a transition fuel.