The World Bank Group’s Early Support to Addressing the Coronavirus (COVID-19): Economic Response (April 2020-June 2021)

Chapter 3 | Relevance of the World Bank Group Early Response

Highlights

The relevance assessment focused on whether the World Bank Group COVID-19 economic interventions were (i) tailored to country and sector needs; (ii) designed based on diagnostics, lessons from past crises, and understanding of trade-offs; and (iii) based on the Bank Group’s comparative advantages.

The Bank Group’s early response generally was highly relevant to low-income countries, which were the ones most in need. Within countries, there was considerable variation in the extent to which Bank Group support went to sectors with greater needs.

Macrofiscal support (including social safety nets) via development policy financing was relevant to client governments. International Finance Corporation and Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency support to client firms in the financial sector; micro, small, and medium enterprises; and onlending to facilitate trade flows was mostly relevant.

The Bank Group used lessons from past crises well to inform its early response designs and approaches, including through country analytical work. Similarly, the International Finance Corporation adapted its response to the local context well based on lessons from the 2008 global financial crisis and disbursed effectively to regional clients. The Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency’s support to trade finance activities in partnership with the International Finance Corporation also built on past lessons.

The Bank Group’s assistance built on its comparative advantages. The World Development Report 2022 provided a strong knowledge base to inform country programs, but global knowledge work on the uniqueness of the crisis was missing (World Bank 2022e). The Bank Group also did not reflect in its operations lessons from developed countries on addressing the economic implications of the COVID-19 crisis. Although the early response benefited from the Bank Group’s global footprint, country office staff needed greater clarity on crisis protocols to be more relevant. Finally, data gaps exist that may impede targeted responses in future crises.

We assessed the relevance of the Bank Group’s response on three dimensions. Relevance means “doing the right things in the right places,” that is, deploying interventions that address countries’ and sectors’ needs to cope with the economic implications of COVID-19. To assess relevance, we evaluated three dimensions: (i) the extent to which Bank Group tailored its response to country and sector needs; (ii) the extent to which Bank Group’s response was informed by diagnostics, lessons from past crises, and understanding of trade-offs; and (iii) the extent to which the Bank Group used its comparative advantages (global knowledge, financing, and global footprint) to tailor its response. We also assessed whether the Bank Group prepared for a future targeted response by collecting the right data.

Relevance for Countries and Sectors

We assessed the relevance of Bank Group support to countries and sectors by comparing their needs with the support that the Bank Group provided to them. First, we constructed need scores related to the economic implications of COVID-19 at the country and sector levels. Second, we measured the strength of Bank Group support received as the ratio between the country’s total amount of received support and its GDP (that is, the support received per dollar of GDP). We calculated sector need scores using harmonized indicators from the World Bank Business Pulse Surveys and the World Bank Enterprise Survey follow-up on COVID-19.1 Third, we compared the need scores to the strength of Bank Group support received to assess the relevance of the Bank Group’s interventions. (For a full description of the methodology, see appendix A and Naeher, Narayanan, and Ziulu 2022.)

To assess country and sector relevance, we developed country and sector need scores as proxy measures of the overall degree to which a country or a sector was adversely affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. The country need score aggregates micro (firm-level) and macro (country-level) data across nine aspects of the economy into a single country-level composite index. The sector need score aggregates micro (firm-level) and macro (country-level) data for each aspect of the economy within a country. The nine aspects of the economy used to measure needs are (i) education, (ii) health, (iii) social protection, (iv) public finance, (v) financial sector, (vi) economic fitness, (vii) agriculture, (viii) manufacturing, and (ix) services.2 As an example, the analysis assumes that countries with fewer hospital beds and more reported deaths tend on average to be more vulnerable to the shocks triggered by COVID-19. We selected the nine sectors and the main indicators and subindicators associated with them based on data availability and similar existing approaches in the economic literature (appendix C).

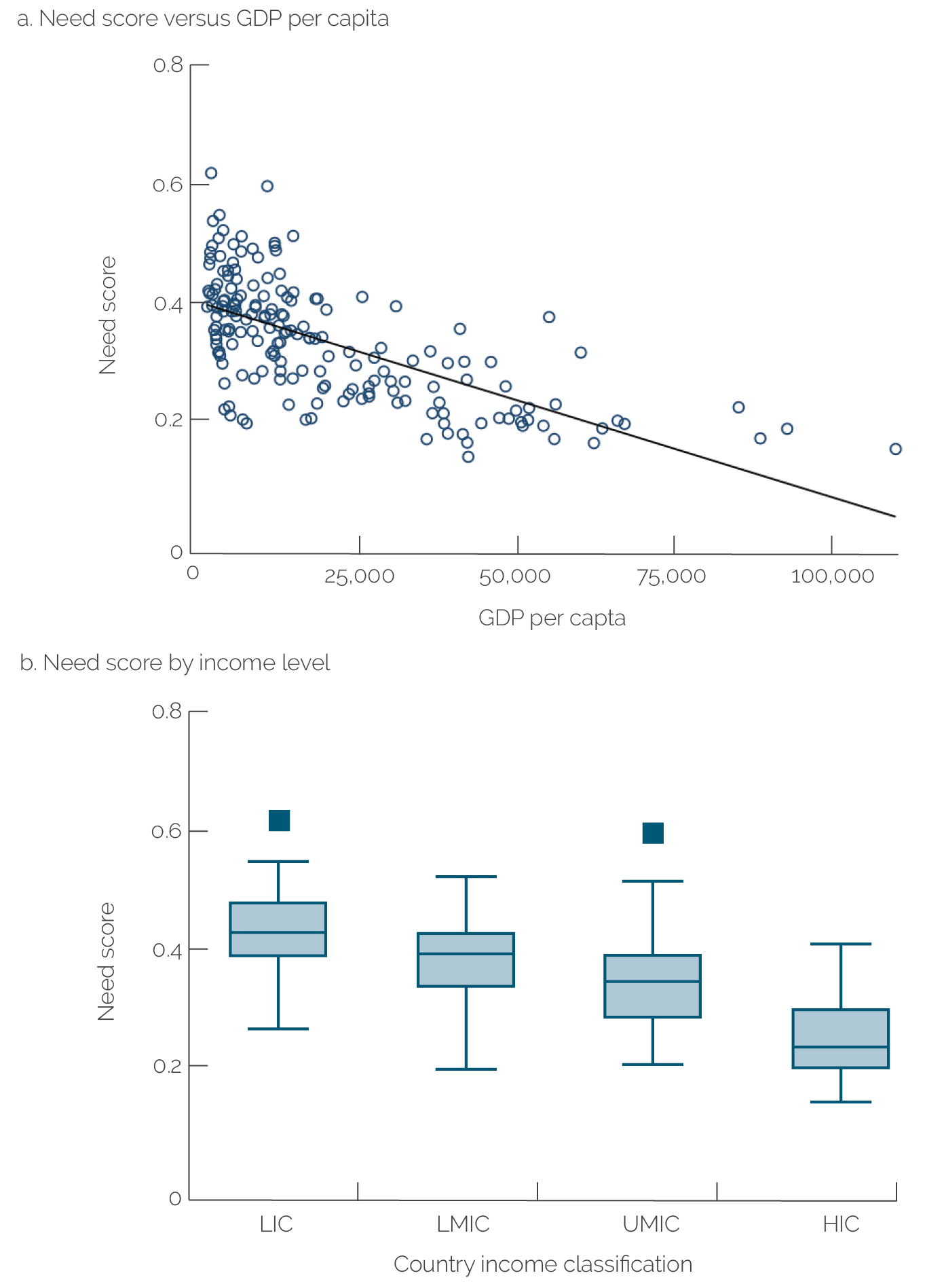

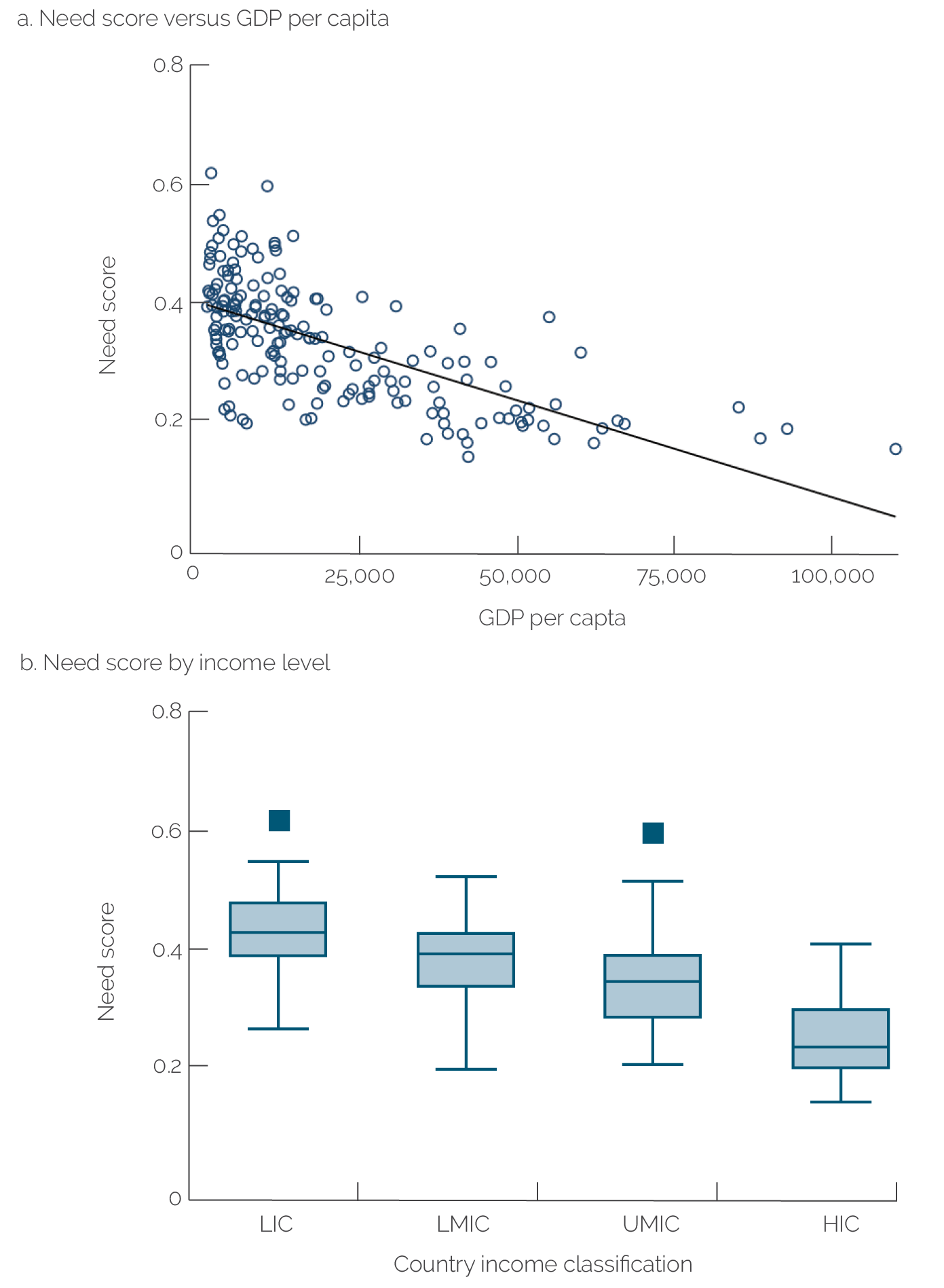

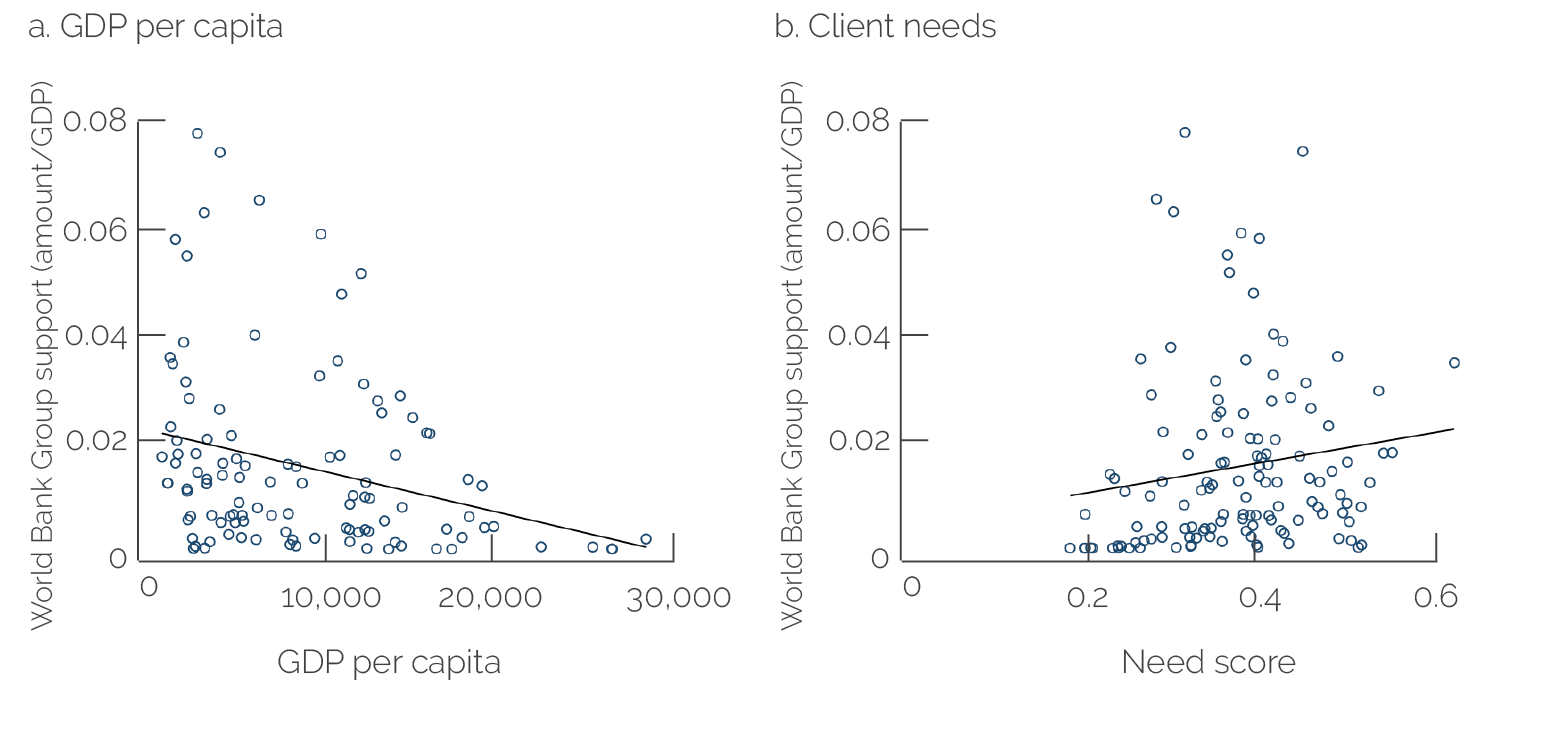

Overall, Bank Group support to countries was relevant because it focused on LICs, which tended to have greater needs for support to address the economic implications of COVID-19. Figure 3.1 shows that need score estimates were higher in LICs. Figure 3.1, panel a depicts the relationship between the need score and per capita GDP. Figure 3.1, panel b shows the ranges of the need score estimates for each income group. Both graphs show a clear negative relation between countries’ need score and income levels, indicating that LICs tended to be more vulnerable and in need of support than richer countries during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. It is important to note that the need score estimates for poor countries vary widely, with estimates ranging from 0.26 to 0.62 in the group of LICs. This indicates that not all poor countries suffered equally under COVID-19. In fact, there are several examples of LICs with need scores well below the average scores of higher-income groups. Figure 3.2 shows the relationships between Bank Group support (expressed as the total amount of support per dollar of GDP) and countries’ per capita GDP (panel a) and between Bank Group support and the need score (panel b). The negative relation between Bank Group support and per capita GDP indicates that the Bank Group’s early support in response to COVID-19 tended to be larger (relative to the size of the benefiting countries’ economies) in poorer countries. Given the greater vulnerability of poorer countries, as shown in figure 3.1, the Bank Group’s early response to COVID-19 provided relatively more support to countries with greater needs for support.

Figure 3.1. Relationship between Countries’ Income Levels and Need Score Estimates

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: The line in panel a represents the fitted values of a bivariate linear regression of need score on GDP per capita. In panel b, the boxes represent the range of values between the 25th and 75th percentile (including the median), the ends of the whiskers represent the lower and upper adjacent values, and the dots represent outliers. Countries with World Bank Group support (amount/GDP) greater than 0.1 are excluded. The need score is a normalized composite measure constructed using the methodology described in appendix C. Data are for 2020. GDP = gross domestic product; HIC = high-income country; LIC = low-income country; LMIC = lower-middle-income country; UMIC = upper-middle-income country.

Figure 3.2. Relevance of World Bank Group Support in Relation to Initial Conditions

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: The line in each graph represents the fitted values of a bivariate linear regression of the variable on the y-axis on the variable on the x-axis. High-income (nonclient) countries and countries with World Bank Group support (amount/GDP) greater than 0.1 are excluded. Data are for 2020. Robustness checks are described in appendix C. GDP = gross domestic product.

However, some countries with high needs received limited Bank Group support on the aggregate nine aspects of the economy used to measure the country need scores. Angola, Bangladesh, Gabon, India, Lebanon, Mongolia, Nigeria, the Philippines, South Africa, and Zimbabwe had country need scores above the median, taking into account all nine aspects of the economy (education, health, social protection, public finance, financial sector, economic fitness, agriculture, manufacturing, and services). Nevertheless, they received limited support from the Bank Group in aggregate on these nine areas. It is important to note that these countries may have not requested assistance from the Bank Group because they relied on other partners or on their own internal resources to address sectors’ needs, may have limited ongoing programs with the Bank Group, or may be in nonaccrual status.

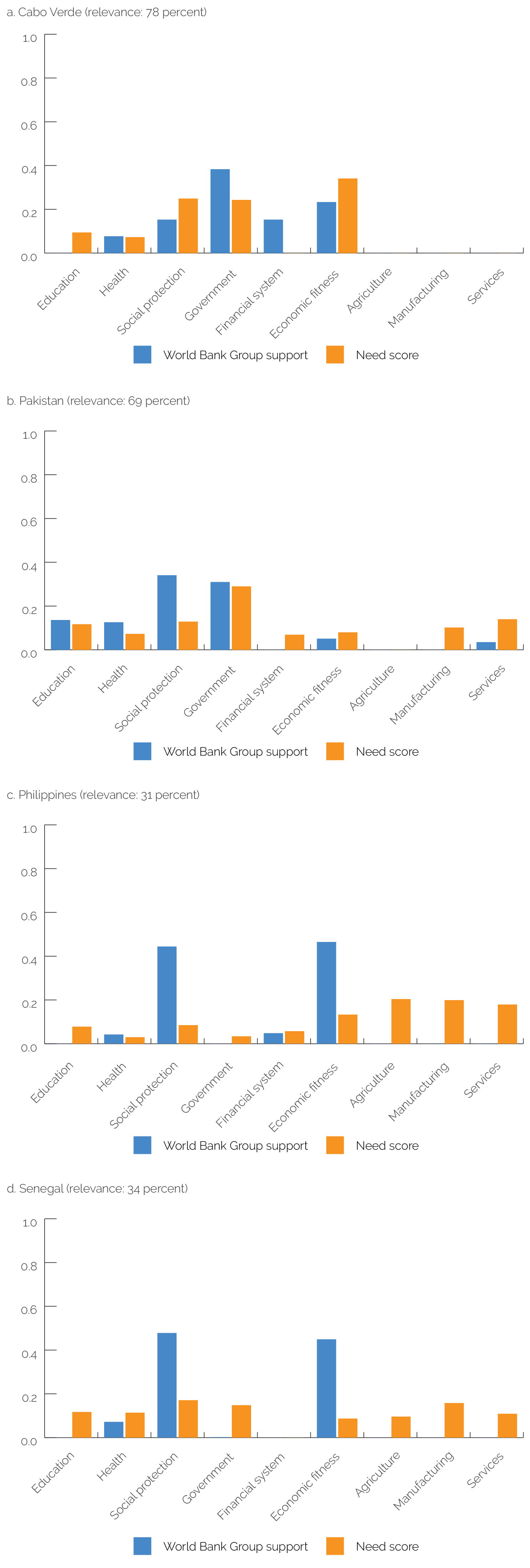

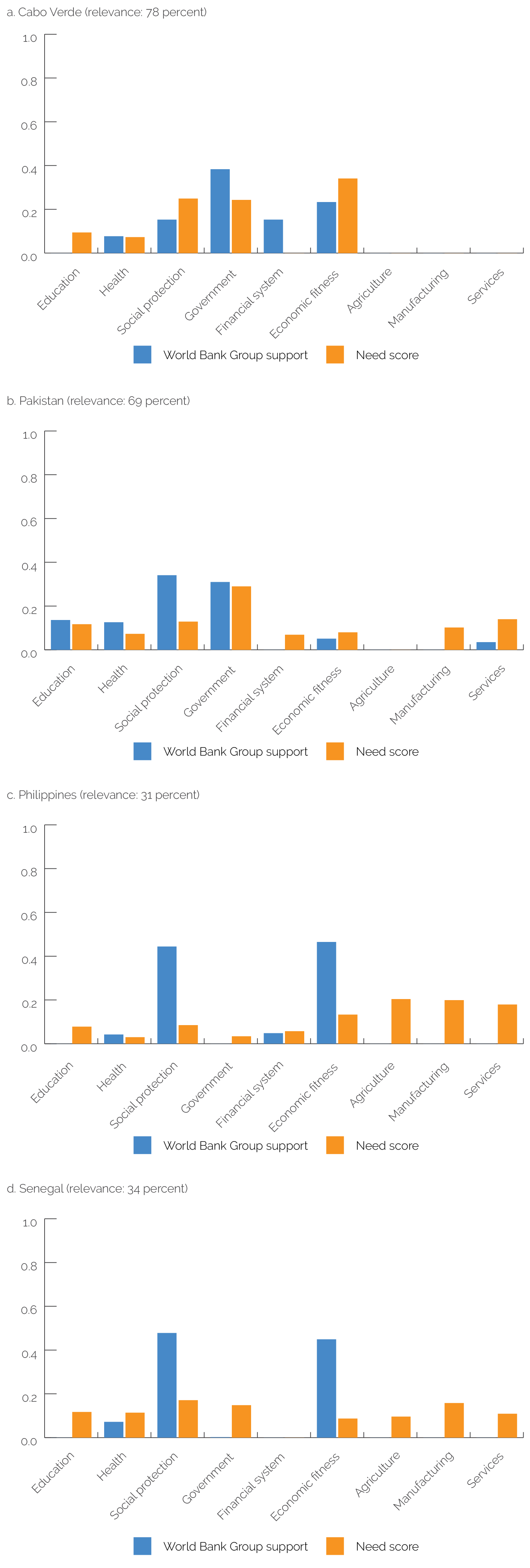

Within countries, the Bank Group’s support for sectors with greater needs varied. Figure 3.3 shows the sector-specific need score estimates and normalized distribution of Bank Group support for select country case studies (note that for some countries, data are missing for some sectors). Each graph also reports the relevance score, which is calculated based on comparing the distribution of Bank Group support (indicated by the blue bars in figure 3.3) with the need score (orange bars). These results give rise to several interesting insights. There is considerable variation in the degree to which Bank Group support aligned with the sector-specific need scores in each country. For example, in Cabo Verde and Pakistan, there was a strong correlation between the need scores and the relative magnitude of Bank Group support to each sector, corresponding to relevance scores of 78 percent and 69 percent, respectively. By contrast, the match between sector-specific needs and Bank Group support was weaker in the Philippines and Senegal,3 where the relevance scores were only 31 percent and 34 percent, respectively. Figure 3.3, panels c and d show, for example, that the Bank Group’s support in these countries focused mainly on social protection and economic fitness, as highlighted in the parallel IEG evaluation on preserving lives (World Bank 2022d). However, the Bank Group did not provide support for agriculture, manufacturing, or services in either country, although these sectors are estimated to have had relatively large needs (or vulnerabilities) compared with other sectors.

The World Bank held back support to a few countries, both in terms of commitments and, in some cases, disbursements, but these cases do not affect the overall relevance of the response because they were limited by government capacity. Because of governance gaps (for example, anticorruption efforts) and regressing policy reforms (for example, structuring fast disbursements to citizens), a few clients (including Nigeria and Zambia) did not get the necessary commitments during the pandemic (according to IEG interviews). In some cases, DPF may have been an appropriate instrument, but the World Bank held back its use based on country conditions and risk to development outcomes (for example, in South Africa). In a few cases (for example, Ecuador), a sound overlapping engagement with the IMF helped clients emerge out of the crisis faster than peers within the Region. In other cases (for example, Nigeria), clients’ structural issues limited the uptake of World Bank support within a reasonable time frame (12–18 months since commitment) during a pandemic (box 3.1).

Figure 3.3. Within-Country Needs Analysis by Sector versus World Bank Group Support in Case Study Countries, Sample

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: Depicted values of World Bank Group support, need score, and relevance score are normalized values constructed using the need score analysis methodology described in appendix C. The relevance score (ranging from 0 to 1) is converted to a percentage here for illustrative purposes for case study countries. If data on the indicators used in the construction of the need score for a sector are missing, then no (orange) bar is shown for that sector. Data are for 2020.

Box 3.1. Nigeria: Client Structural Issues as Constraints on World Bank Support

Complexity in Nigeria starts with the intergovernmental fiscal relations among the federal government, the 36 states of the federation, and 774 local governments. To date, the World Bank Group has also not done sufficient advisory services and analytics (World Bank) or advisory services work (International Finance Corporation) to clarify the responsibilities and accountability of the various levels of government, including at the state level. In this context, the World Bank supported a COVID-19 response financed by (i) a US$100 million International Development Association credit allocated to Nigeria through the fast-track COVID-19 facility under the crisis response window and Nigeria’s allocation under the 19th Replenishment of the International Development Association and (ii) a US$14 million grant through the Pandemic Emergency Financing Insurance Window, which provides financial support to International Development Association–eligible countries if major multicountry disease outbreaks occur. Despite major efforts by World Bank staff, at the time of this evaluation, the Pandemic Emergency Financing Project had not been disbursed because of the complexity of the federal structure and the well-documented dysfunction of the state and national governments. An upcoming Program-for-Results (2022) offers some hope for addressing the incentives for states to align with the federal government.

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

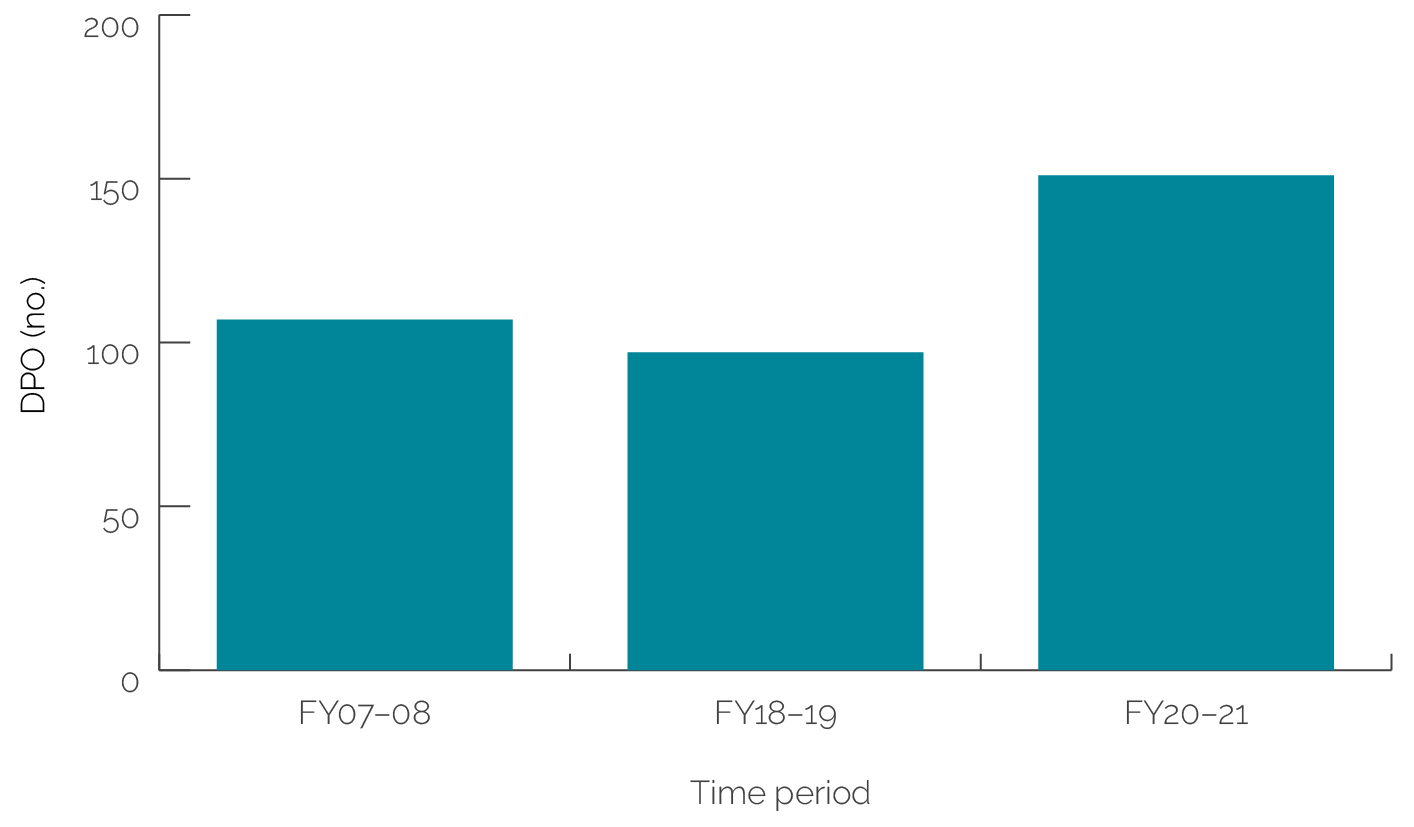

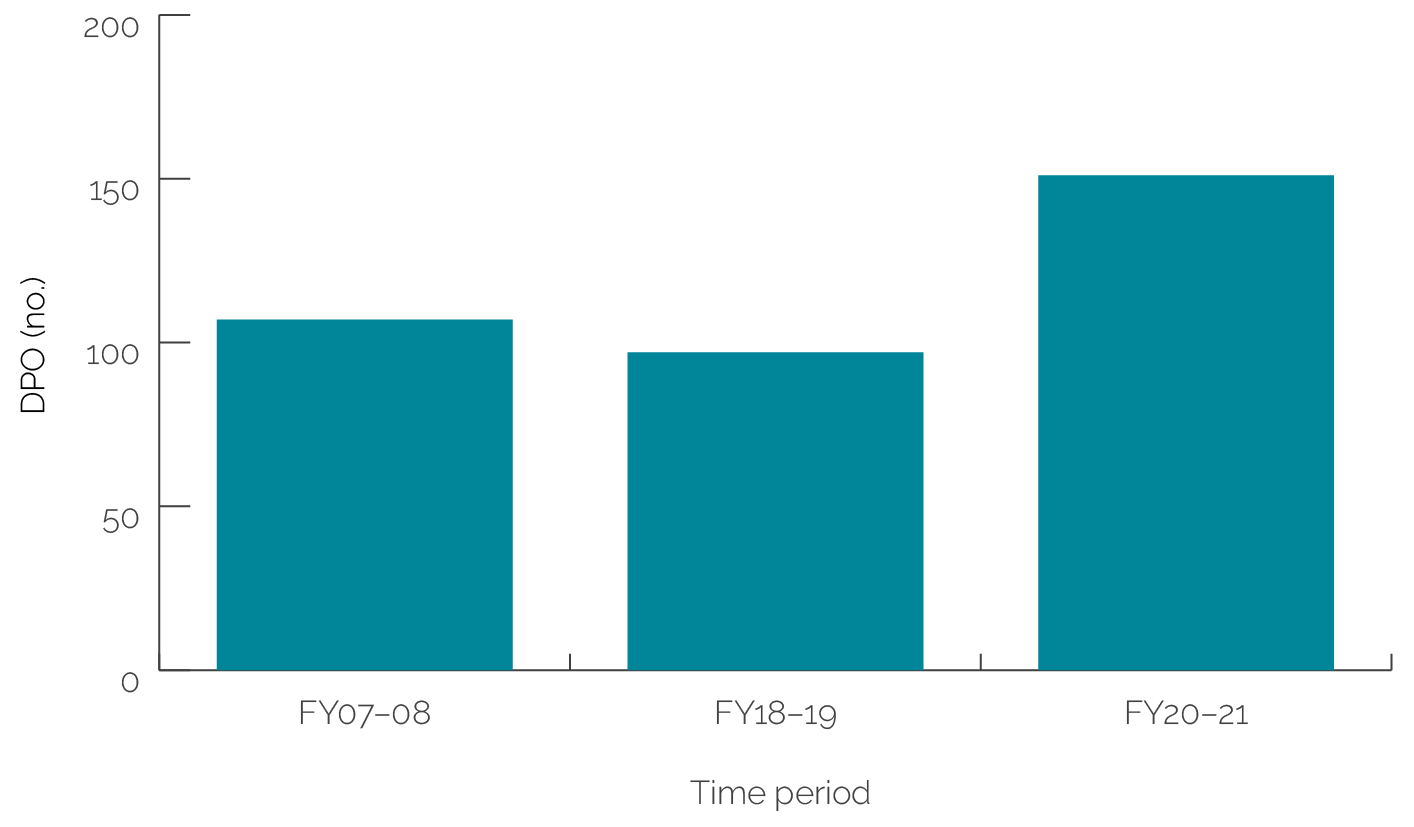

Macrofiscal support via DPF was highly relevant to clients. Given its flexibility and relatively agile disbursing ability, the World Bank used the full suite of DPF instrument variations to address the economic implications of COVID-19. Macrofiscal support was higher in volume commitments than during the global financial crisis (2008) and higher than the prepandemic level of support, suggesting the relevance of the response in addressing the economic shock felt in client countries (figure 3.4). Besides the stand-alone and series DPOs, the World Bank approved seven DPF CAT DDOs and one DPF policy-based guarantee. Under a DPF CAT DDO, budget support is disbursed on the activation of a catastrophe trigger, typically the declaration of a national emergency or disaster. Generally, the DPOs with additional components disbursed faster than the investment projects and played a relevant role in budget support in pillar 4 (institution strengthening), followed by pillar 3 (sector support). This focus broadly aligned with the Bank Group’s June 2020 COVID-19 response Approach Paper (World Bank 2020e).

Figure 3.4. Macrofiscal Support via Development Policy Operations, Select Time Periods

Source: Independent Evaluation Group calculations and Operations Policy and Country Services Development Policy Actions Database (April 2022).

Note: DPO = development policy operation; FY = fiscal year.

The IFC and MIGA early response was essential to supporting local banks in providing crisis financing. Without IFC and MIGA’s response, existing clients in the financial sector would have either defaulted on loans or cut back on their onlending programs, leading to severe disruption for firms (especially MSMEs) and supply chains. Without IFC and MIGA support, clients would have also launched employee reduction programs, leading to income reductions for workers and households (per key informant interviews and case studies). See box 3.2 for examples.

Box 3.2. The International Finance Corporation and Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency Early Response

In Indonesia, local banks did not have the risk appetite to provide large financing to large real sector firms, mainly because of uncertainty about the direction of the pandemic. One example was Trans Corp, an existing International Finance Corporation (IFC) client that operated in the consumer segment. Trans Corp’s businesses largely counted on local consumers, and the pandemic severely affected local demand. Trans Corp faced short-term liquidity problems in 2020 as revenues fell because of temporary closures of its facilities in response to the government’s containment measures. Without IFC’s liquidity support to Trans Corp during the pandemic, Trans Corp would have laid off most of its employees. Moreover, the layoffs would have affected the company’s relationship with its suppliers, most of which were small and medium enterprises (SMEs) in the retail segment of its business. Absent IFC intervention, the company would have had to find resources to reduce its expenses or sell some of its real estate assets.

The vast majority of VP Bank’s portfolio in Vietnam focused on the retail and SME segment. Without IFC’s support, VP Bank would have raised liquidity support from other sources and collected only approximately half the amount it received from IFC. This lower liquidity would have prevented VP Bank from restructuring half of its US$1 billion loans affected by the pandemic, which would have harmed its SME clients. VP Bank’s full use of the Global Trade Finance Program limits during the pandemic indicates liquidity shortages in the market and limited support from international banks in Vietnam, even though Vietnam was one of the better performing countries during the pandemic (in terms of low-cost response to managing COVID-19, for example, rapidly rolling out moratoria on debt repayments, suspending social insurance payments, and increasing the firm-level interest deductibility cap).

The relevant support of IFC and the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency enabled ProCredit’s subsidiaries (Western Balkan countries) to onlend to SMEs, including for climate financing, and manage liquidity risks in a timely manner. The Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency and IFC collaborated at the time of the due diligence of ProCredit to assess the environment and social aspects of the project and agreed with ProCredit on specific targets for climate financing to SMEs.

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

MIGA’s early response supported firms in the substantial- to high-risk categories, predominantly in Africa and in Europe and Central Asia, and was relevant. Based on MIGA corporate portfolio risk analysis,4 most political risk insurance exposure gained via the MIGA early response was at the high tier of the country risk spectrum (44 percent at entry, 47 percent at the end of the evaluation period).5 Analysis of the non-honoring guarantee portfolio indicates that the MIGA non-honoring guarantee projects were in countries with risk assessed as substantial (84 percent at entry, 72 percent at the end of the evaluation period).6 The Africa and Europe and Central Asia portfolios experienced rising country risk throughout MIGA support. The rising risk points to MIGA’s relevant role in risk mitigation and capital mobilization under guaranteeing project risk in countries where commercial financing was needed.

Informed Design

The Bank Group used lessons from past crises well to inform its early response designs and approaches. Consistent with lessons learned from past crises, country analytical work contributed to the World Bank’s early response and aimed to address the pandemic through a three-pronged approach: budget, public health, and MSME support. In Serbia, the World Bank’s analytical work via Country Economic Memorandum and the “Western Balkans Regular Economic Report” informed the early response programs (World Bank 2020a, 2020f). Similarly, IFC adapted its response to the local context well based on lessons from the 2008 global financial crisis. IFC launched two new platforms—the Global Health Platform and Base of the Pyramid Platform—to better respond to clients’ needs at the time of the crisis. In Georgia, prior high-quality and tailored analytical work had identified key vulnerabilities (World Bank 2018); this work helped the World Bank quickly put together a customized program focused on those vulnerabilities. IFC, for example, provided Liquid Telecom with a flexible and efficient support package for the Sub-Saharan economy to digitalize firm activities. This project was critical at a time when many offline duties were shifted online because of COVID-19, allowing more people to perform their jobs from home and permitting Liquid Telecom to dispose of more capital to expand the company’s digital infrastructure network in fragile markets (such as Chad, Sudan, and Zambia). In South Africa and the Balkans, MIGA had expected severe pressures in some of its guarantee holder’s subsidiaries during the pandemic and facilitated capital relief solutions. MIGA’s support to trade finance activities in partnership with IFC is an innovative product based on lessons from past crises that backstops losses for client banks and supports MSMEs that have insufficient access to credit, training, and certification to become part of value chains.

MIGA’s early response was less relevant when it did not fully consider country conditions. Although highly complex at the time of crisis, including the COVID-19 crisis, assessing which countries are most in need of support is important to ensure that resources are targeted to vulnerable clients (box 3.3).

Country office staff continue to need greater clarity on specific crisis protocols, mechanisms, and guidelines for developing targeted approaches addressing economic implications of the COVID-19 crisis. Many country teams welcomed diagnostic tools, real-time sector analysis papers, and the World Development Report 2022. However, for day-to-day matters, they seek greater clarity and preparedness for the next crisis in (i) a country-level emergency procedures playbook that outlines the flexibility of instruments, policies, and procedures and informs crisis-time diagnostics at the country level; (ii) real-time dashboards and lighter versions of the World Development Report to inform integrated sector approaches; (iii) real-time guidance on strategic portfolio choices informed by continuing analysis of global response strategies; and (iv) surge-capacity plans (when and how to increase fixed- and variable-cost resources in country offices) to support staff welfare.

Box 3.3. Assessing Country Conditions: The Panama and Africa Cases

In Panama, the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA) issued a Non-Honoring of Financial Obligations of a state-owned enterprise guarantee to help Banco Nacional de Panama raise financing for a US$1 billion trust fund established by the Ministry of Economy and Finance to mitigate the economic effects of the pandemic. The trust fund was expected to provide loans to onshore commercial banks for emergency liquidity and lending to small and medium enterprises and companies in priority sectors. The MIGA project provided non-honoring guarantees to Goldman Sachs and Société Générale for providing senior unsecured loans totaling US$500 million to Banco Nacional de Panama. The Ministry of Economy and Finance contributed an additional US$500 million to the trust fund through the Rapid Financing Instrument from the International Monetary Fund. As of mid-May 2021, liquidity under the trust fund has not been drawn by any bank. Although assessing country conditions is complex, especially at the time of a crisis, and although the MIGA non-honoring guarantee was endorsed by the International Monetary Fund, its low relevance could have been expected in view of the strong standing of Panama’s financial sector in both capital markets and private credit markets and the fact that Panama is a fully dollarized economy. The design of the trust fund was also such that small and medium enterprises were not the primary project beneficiary, despite the original project’s objectives.

MIGA issued guarantees to the headquarters of FirstRand (in South Africa) as part of its COVID-19 response under the capital optimization program. MIGA expected that the capital relief generated from these guarantees would be deployed to seven FirstRand Group subsidiaries (across Sub-Saharan Africa) to absorb deleveraging pressures during the pandemic. However, capital relief was granted to tier 1 bank subsidiaries with relatively large market share (Botswana and Eswatini) and not to tier 2 bank subsidiaries with smaller market shares in countries in need (for example, Ghana, Mozambique, and Nigeria).

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Comparative Advantages

The Bank Group’s comparative advantages during a crisis predominantly lie in its ability to advance global knowledge and translate it into financial and advisory support to governments and firms, and in its global footprint. IEG corporate evaluations (2010–22) have provided extensive evidence that these are areas where the Bank Group has comparative advantages over other multilateral and regional development partners in responding to an economic crisis.

The World Bank’s early response was well informed by existing diagnostic tools. The World Bank’s early response was broadly aligned with—and structured based on—diagnostics, with additional financing for emergency government budget response to the social crisis and measures to maintain liquidity in the financial sector. The Bank Group relied on several existing analytical instruments to tailor its emergency COVID-19 response mechanisms. These include the IMF’s Article IV consultations, the debt sustainability analysis, the Financial Sector Assessment Program, household and business enterprise surveys, Country Economic Memorandums, and the three-year Country Program Frameworks, which the World Bank augmented with targeted additional financing to support country-specific fiscal, monetary, and financial policy.

Yet the World Bank did not conduct novel global knowledge work to deepen understanding of the unique characteristics of the evolving crisis or reflect on relevant lessons from developed countries. Despite the novelty of the pandemic and its implications globally, the World Bank did not conduct new global diagnostics to inform existing portfolio management and strategy or repurpose policy and institutional strengthening work. Also, the Bank Group did not seem to identify, analyze, and apply lessons from developed countries on how to address the economic implications of COVID-19. This conclusion regarding the gap in novel global knowledge work was based on two sets of reviews: (i) IEG’s review of the dashboards of the Multilateral Leaders Task Force on COVID-19 and the World Bank COVID-19 response was conducted to assess the availability of global knowledge work at the level of the World Development Report,7 and (ii) IEG’s review of global economic or meta-economic policy trackers was conducted to assess the Bank Group’s contributions to global knowledge work.8 Developed countries’ COVID-19 response programs (for example, in New Zealand and Switzerland) focused on, for example, payments to affected workers and households, including in high-contact sectors, which the Bank Group could have considered for some client countries (WEF 2020). Although some lessons from advanced countries may not be relevant for or applicable to the Bank Group’s clients, stakeholders we interviewed indicated that the Bank Group did not seem to have a way to systematically tap into the knowledge and experience of advanced countries to inform the dialogue with clients and to discuss whether lessons from these countries were relevant and applicable (or not).

The Bank Group’s early response leveraged its global footprint well. The Bank Group’s response benefited from its global footprint. Moreover, as the parallel IEG evaluation on preserving lives notes, “World Bank staff responded to enormous demands to deliver extraordinary support in unprecedented circumstances” (World Bank 2022d, 92). Bank Group staff adjusted well to remote and hybrid work overall, enabling them to react to client needs in an agile fashion. Bank Group staff managed the early response despite ongoing disruptions in engagement with country authorities and continued mobility restrictions that affected supervision efforts and clients’ implementation capacity. Staff in country offices demonstrated leadership at various levels despite facing a “triple whammy” of new crisis-related responsibilities: personal and family welfare, the welfare of existing clients, and the welfare needs of potential new clients (according to key informant interviews and case studies).

Data Gaps for a Targeted Response

Limited evidence is available on how the World Bank leveraged global data and its access to country budget systems to ensure that its support for the COVID-19 crisis reached the most vulnerable households. Tracking the flow of funds through the case study country budget departments to the provincial and community levels will require substantial analytics on community employment programs; local digital communities can help track the impact on household and enterprise finances of credits to bank cash cards and e-wallets. Furthermore, in the social sector–linked DPFs, the most visible pandemic response of the World Bank has been the conditional cash transfer programs. In response to advocacy group requests, the validation of these programs—particularly to public and commercial stakeholders—needs to be articulated better via a consultative group of real economy representatives. The support to Croatia, a noncase country, may be a best practice so far (box 3.4).

Box 3.4. Tracking World Bank Funds in Croatia

The World Bank’s budget support to Croatia (Crisis Response and Recovery Development Policy Operation, US$300 million, 2020) and investment project support (Helping Enterprises Access Liquidity in Croatia investment project financing, US$240 million) both used the capacity of the national development bank (the Croatian Bank for Reconstruction and Development), state audit office, and state financial agency for tracking trade, financial, and export data. Disbursement information and progress across key results indicators (for example, the number of exporters receiving subloans, the number of firms served in lagging regions, and the increased use of the European Union’s parallel financing by the Croatian Bank for Reconstruction and Development) were set up to be monitored at various levels of government for both projects, seamlessly leveraging data systems from the three organizations.

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

No evidence is available on how the Bank Group used its global reach to align with extrabudgetary funds (EBFs) that many client countries set up in parallel with the crisis but conflated with the specific vulnerabilities of the pandemic’s economic implications. More than 40 client countries set up EBFs to support firms and citizens, especially in Africa (figure 3.5). Such COVID-19 response funds from governments draw mainly on budgetary resources, but they usually target pooling private donations, public resources, and external sources of finance. Although most funds are not appropriated in the budget (that is, they are off-budget), some have used on-budget arrangements (for example, appropriations through specially created programs or subprograms of the budget). Most funds operate through separate banking, financial management, and reporting arrangements outside regular public finance management channels. No evidence was available to show the interactions between the World Bank support and the EBFs.

Figure 3.5. Countries with Extrabudgetary COVID-19 Response Funds

Sources: Independent Evaluation Group; International Monetary Fund.

Note: Dots indicate the countries that set up extrabudgetary funds to address the economic implications of COVID-19.

We could not assess the motivations and risks related to EBFs set up by clients to complement multilateral support during COVID-19. There are several motivations behind creating EBFs in the current crisis; a central one has been to accelerate government spending. Other reasons include the need for a high level of government discretion, to pool public and private resources, to coordinate interventions across different sectors and levels of government, or to ring-fence COVID-19 spending. EBFs are often regarded as suboptimal (Rahim et al. 2020). In the absence of strong safeguards, funds with independent spending authority—bypassing normal budgetary and expenditure controls—can dilute accountability and weaken fiscal control, creating significant fiscal risks and corruption vulnerabilities. The COVID-19 crisis heightens many of these risks. The rush to set up funds has led in some cases to a legal vacuum in which their purpose, management, and oversight are insufficiently defined. The pressure on governments to respond swiftly to the emergency has often led to the relaxation of ex ante financial controls and procurement processes and the weakening of oversight mechanisms. WHO conducted a global survey on EBFs in 2020, the findings of which revealed a wide array of approaches by client countries, but a central question remained on the level of transparency of the EBFs.

- The World Bank Business Pulse Surveys and World Bank Enterprise Survey data set capture 120,000 businesses’ performance across 60 countries in the real sector, including manufacturing, agriculture, and services. The data set captures sector impacts based on sales, labor, wages, liquidity, solvency, and operational performance.

- Many of these aspects of the economy (for example, health and social protection) fall under the subject of the parallel Independent Evaluation Group evaluation on preserving lives, The World Bank’s Early Support to Addressing COVID-19: Health and Social Response. We used them here simply because needs in any of these aspects of the economy could trigger economic distress. Additionally, in this case, we are trying to model a country’s total need to compare with gross domestic product. Finally, using this broad set of aspects of the economy allows for a within-country analysis that permits comparing the World Bank Group response to one aspect of the economy with its responses to other aspects.

- International Finance Corporation support in the Philippines included support to the rural microfinance sector via the Working Capital Solutions envelope.

- The portfolio analysis was conducted via a participatory approach with Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA) economics and risk teams.

- For this analysis, MIGA staff provided a streamlined version of their country risk categories aggregated on a four-point scale characterized in the following descending order: high, substantial, moderate, and low. These four categories consolidate MIGA’s internal political risk insurance ratings from a 10-point scale and its Non-Honoring of Sovereign Financial Obligations and Non-Honoring of Financial Obligations ratings from a 21-point scale.

- Non-Honoring of Sovereign Financial Obligations coverage protects against losses resulting from a government’s failure to make a payment when due under an unconditional and irrevocable financial payment obligation or guarantee given in favor of a project that otherwise meets all of MIGA’s normal requirements.

- See the “Multilateral Leaders Task Force on COVID-19 Vaccines, Therapeutics, and Diagnostics” (http://covid19taskforce.com) and “The World Bank Group’s Response to the COVID-19 (coronavirus) Pandemic” (https://www.worldbank.org/en/who-we-are/news/coronavirus-covid19).

- See “Oxford Supertracker” (https://supertracker.spi.ox.ac.uk/).