Enhancing the Effectiveness of the World Bank’s Global Footprint

Chapter 4 | Challenges and Inefficiencies

The quantitative targets help expand the global footprint, and work program planning and budgeting process is used to tailor the staffing to the country’s portfolio. However, the work program planning and budgeting process and the corporate targets do not guarantee that staffing decisions are sufficiently nuanced to take full advantage of decentralization’s benefits.

The World Bank’s knowledge generation system is largely headquarters based. Access to knowledge from the field remains challenging, while formal knowledge produced by field staff is often less valued and less frequently curated for global use than headquarters-generated knowledge.

Reduced circulation of staff between headquarters and the field, coupled with local staff’s limited exposure to the World Bank’s corporate vision and culture, can contribute to Regional and country silos and undermine the World Bank’s global nature.

There may be an unintended human resource bias toward country programs that host country directors, to the detriment of the Country Management Unit’s smaller country programs. For example, these countries host the largest share of professional staff. These staff are meant to serve nearby country offices, but this may not be working as intended.

There are also some inefficiencies related to the location of practice managers and project task team leaders. For example, the widespread co-task team leaders model is less effective when the task team leaders with accountability and decision-making responsibilities are not located in the client country.

There is untapped potential among locally recruited staff. They have limited opportunities for professional development through mentoring, learning events, and short-term assignments and are less exposed to the World Bank’s common corporate culture.

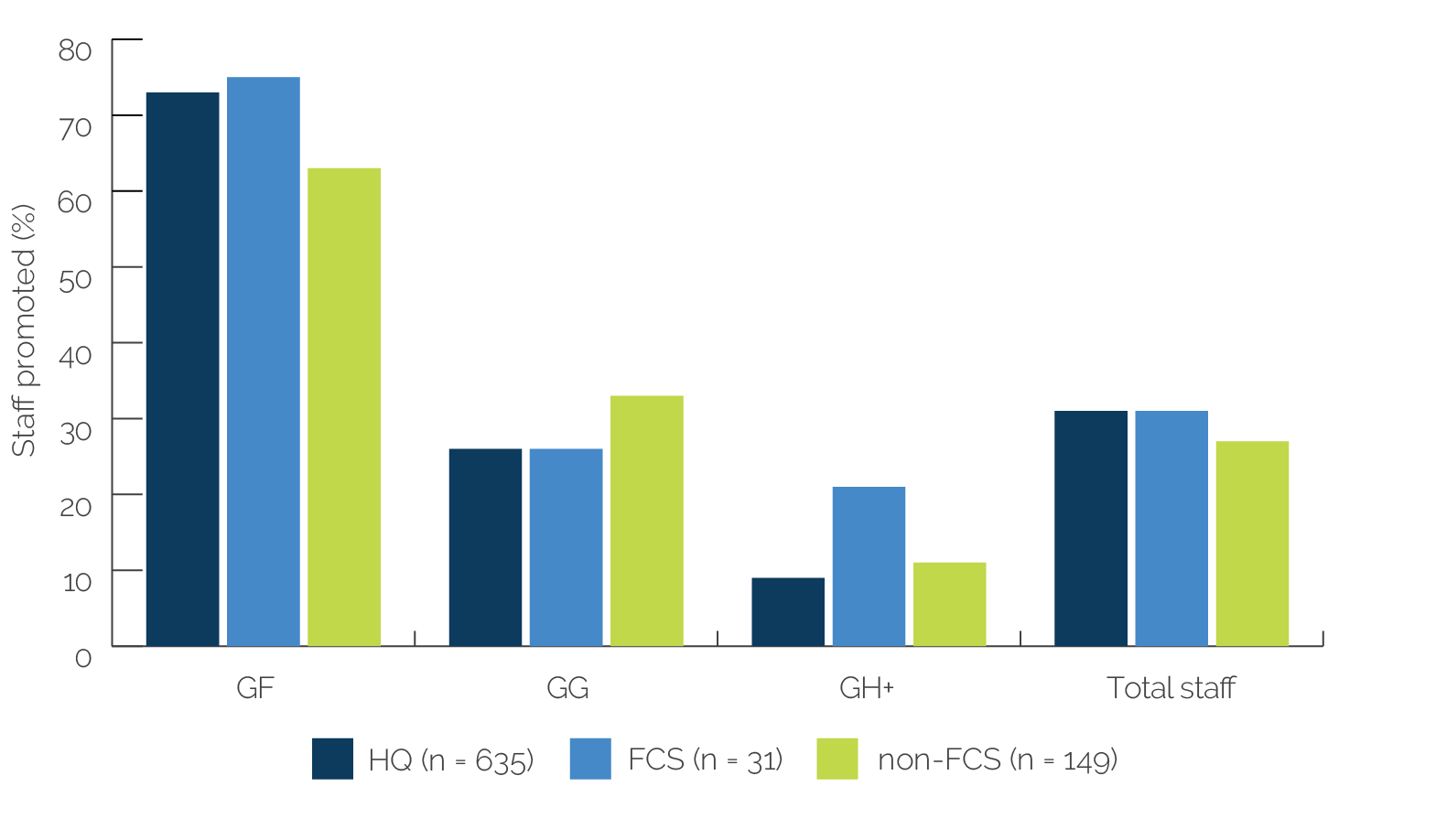

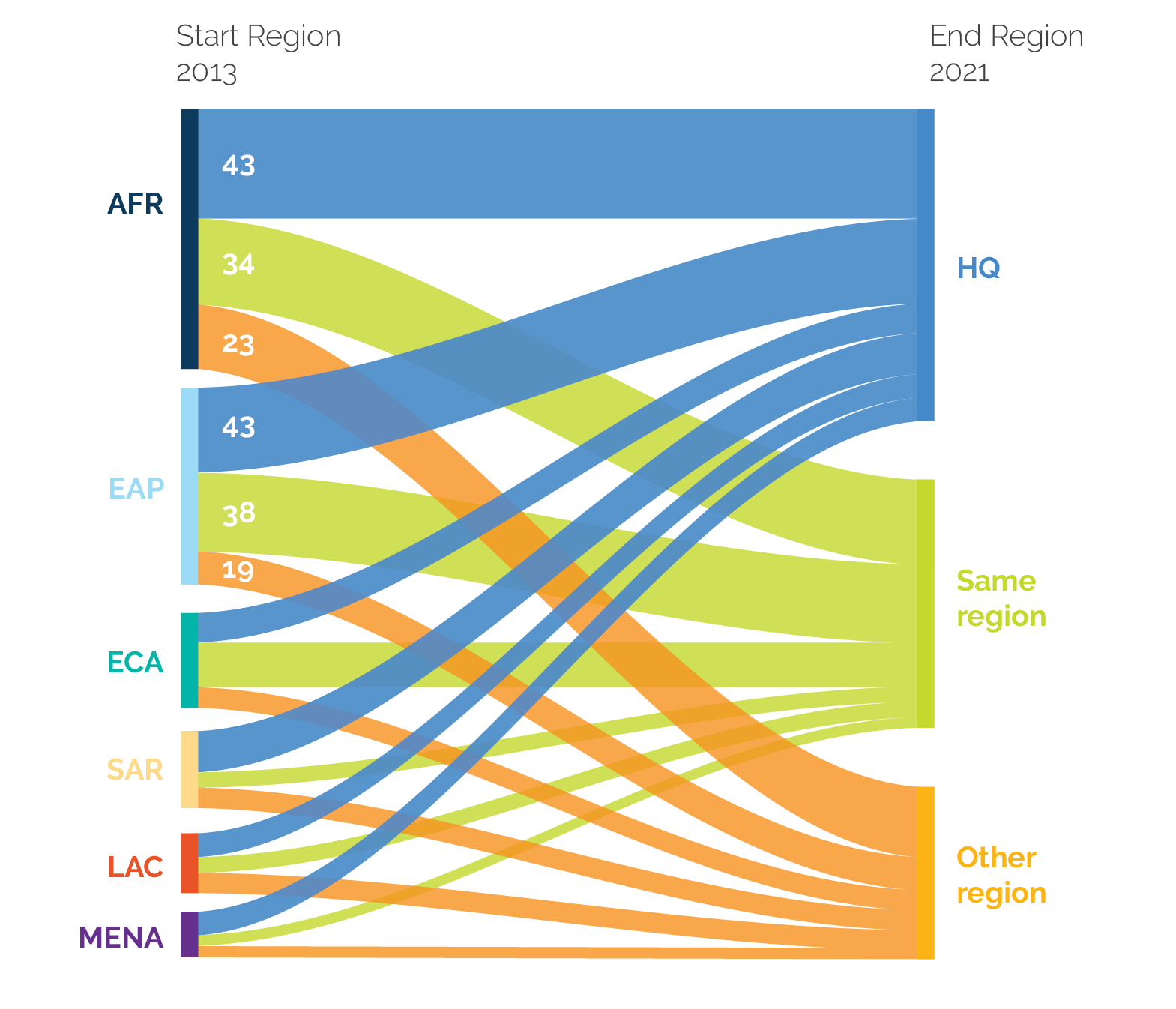

Field assignments do not hinder staff’s career progression or mobility, despite widespread beliefs among international staff that they do. However, international staff in fragile and conflict-affected situation (FCS) countries are more likely to remain in their Region than staff initially located in non-FCS countries.

It is difficult for the World Bank to attract international staff with relevant skills and the right mind-set to field posts in many FCS and lower-income countries. The factors contributing to this are the lower visibility and perceived limited career prospects in smaller countries that do not host country directors. International staff also have objective concerns about lower quality of life, health, and security at field posts in those countries.

This chapter focuses on some key challenges and inefficiencies in the World Bank’s current approach to decentralization, as depicted in the last column of the conceptual framework shown in figure 1.1, and demonstrates how these challenges and some human resources policies (enabling conditions in figure 1.1) undermine the desired effects of decentralization. The chapter contributes to evaluation question 2 and informs evaluation question 3. More specifically, the chapter examines decentralization’s challenges related to strategic direction, structure, decision-making, global knowledge flow and collaboration, and career development for staff and summarizes challenges from IFC’s decentralization experience.

Strategic and Structural Issues

The objectives of the World Bank’s ongoing wave of decentralization are not clearly articulated. It is unclear how the broad quantitative staffing targets that aim to provide more impetus to decentralization are linked to countries’ and Regions’ needs. Early in 2019, to help design the reform, the World Bank formed a high-level working group to contribute to early discussions on possible implications of an enhanced footprint. However, this group was disbanded at the beginning of the implementation, and there is currently no central unit responsible for elaborating the model’s design, providing guidance, monitoring decentralization’s performance and possible impacts on different parts of the World Bank’s work, or suggesting course corrections. The Regions do not articulate any objectives or strategies related to decentralization, either, despite differences in staffing needs and trends across Regions. An exception to this is the Bank Group’s FCV strategy for 2020–25. The strategy articulates the World Bank’s staffing needs for addressing fragility challenges and scaling up the financial support for low- and middle-income countries in FCV situations, but its implementation would benefit from elaborating on the type of staff needed and where they should be deployed to achieve better results.

The broad quantitative targets, without articulating expected outcomes of decentralization and some key guiding principles, do not support making tailored staffing decisions. In some Regions and GPs, the decisions on whom to send to the field were made to meet expected staffing targets. Staff and midlevel managers in interviews were critical of the World Bank for establishing these targets without linking them to clear goals and countries’ development needs. For example, the case studies uncovered instances where practice managers were sent to the field to meet staffing targets without that sector having a substantial portfolio in that Region. There were even more frequent cases of practice managers being sent to the field while leaving most of their GP staff in headquarters. One director noted, “Decentralization is a means to an end. Not the end. We are currently ticking boxes.” In other words, decentralized staffing targets increase the number of staff and managers in the field but do not ensure that decentralization decisions are tailored to country and program needs. The work program planning and budgeting process (Work Program Agreement) that aims to tailor the staffing to the country’s portfolio also does not seem to be sufficient to provide adequate and timely staffing support in some cases.

Decentralization’s impact on the delivery of country programs is rarely discussed in the context of CPFs. The World Bank does not formally link its field staffing to the achievement of CPF objectives. As a result, very few CPFs discuss staff location, nor is there any record of country programs using the CPF process to hold internal discussions about decentralization. Instead, country programs make staffing decisions at the margins in the context of annual Work Program Agreement discussions. Sixteen of the 20 case study countries’ CPFs discuss capacity constraints in implementation, fiduciary processes, safeguards, and monitoring and evaluation, but only a few—such as Afghanistan, Burundi, the Central African Republic, the Solomon Islands, Tunisia, and Vietnam—take the next step of noting the role the World Bank’s footprint plays in addressing these constraints. The Argentina Country Partnership Strategy (FY15–18), for example, says that “expanded engagement at the provincial level may also require additional capacity building at the local level,” but it stops short of saying what the implications of this are for the country office’s staffing levels and composition (World Bank 2014, 47). Only FCS country strategy documents generally discuss the need for enhanced country presence but with uneven coverage. Afghanistan’s Interim Strategy Note (FY12–14), for example, notes that “operational progress is most likely to be achieved with the strong engagement of TTLs who are experienced, reside or spend considerable time in Kabul, and who are persistent in their hands-on engagement with the counterparts and stakeholders” (World Bank 2012, 17). The Solomon Islands Completion and Learning Review noted that “limited on-the-ground presence” was one factor that caused the Country Partnership Strategy program to face “implementation challenges in reaching some objectives” (World Bank 2018b, 17).

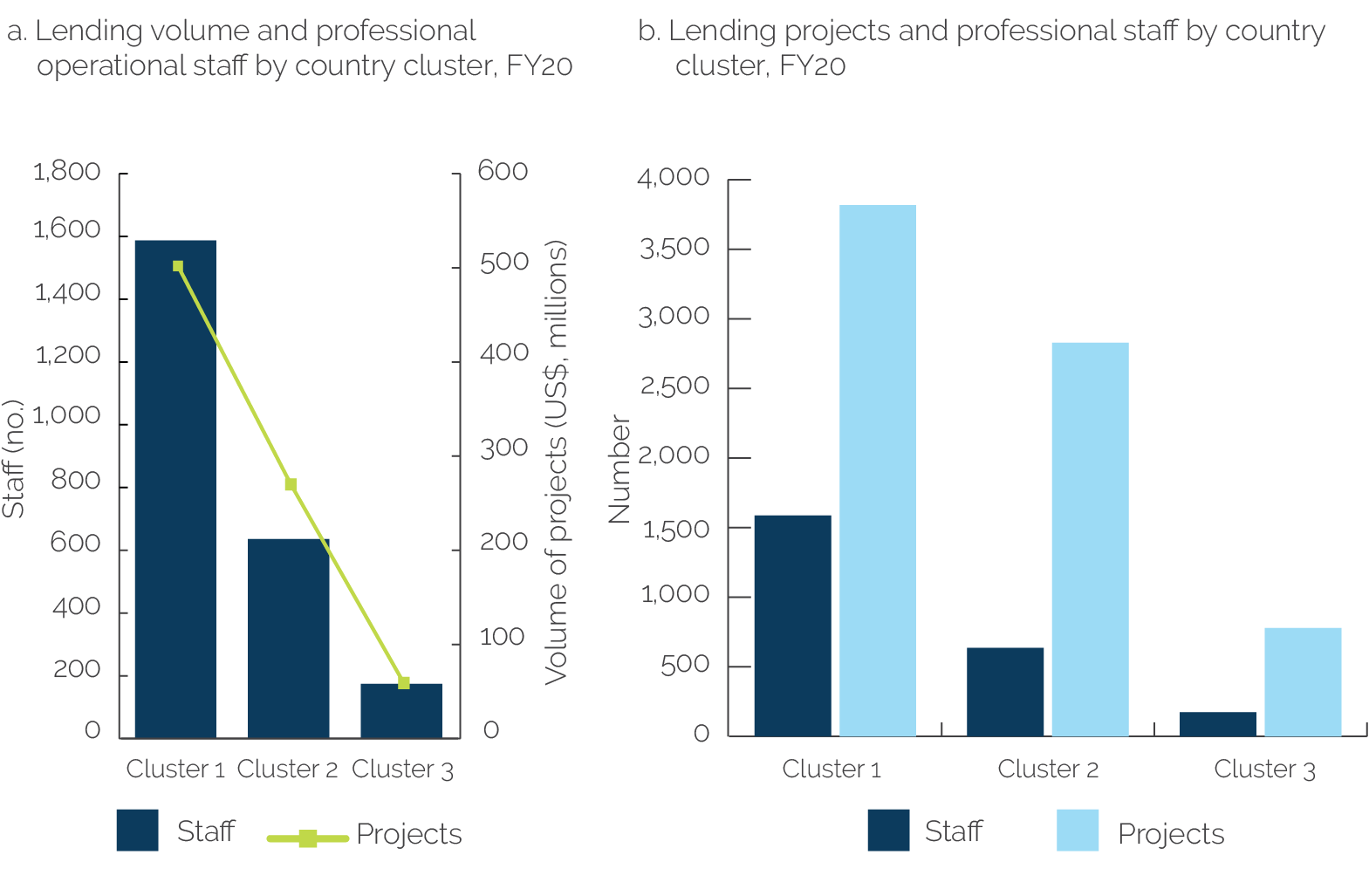

More staff are concentrated in CD countries regardless of those countries’ portfolio size. Placing professional staff near country directors in CMUs has been one of the World Bank’s strategies since 2008 to mitigate the limitation of having Washington, DC, as the only center to serve country offices. Few small countries with limited operational portfolios can justify the cost of having a full-time IRS located in-country. For this (but also other) reasons, IRS, including program leaders and managers, tend to locate in the primary country of the CMU with an assignment to cover all countries in the CMU. As shown in box 4.1, there are significantly more staff per project in the CD country of the CMU than in the CMU’s other country offices.

Box 4.1. Staffing in Countries with Different Decentralization Models

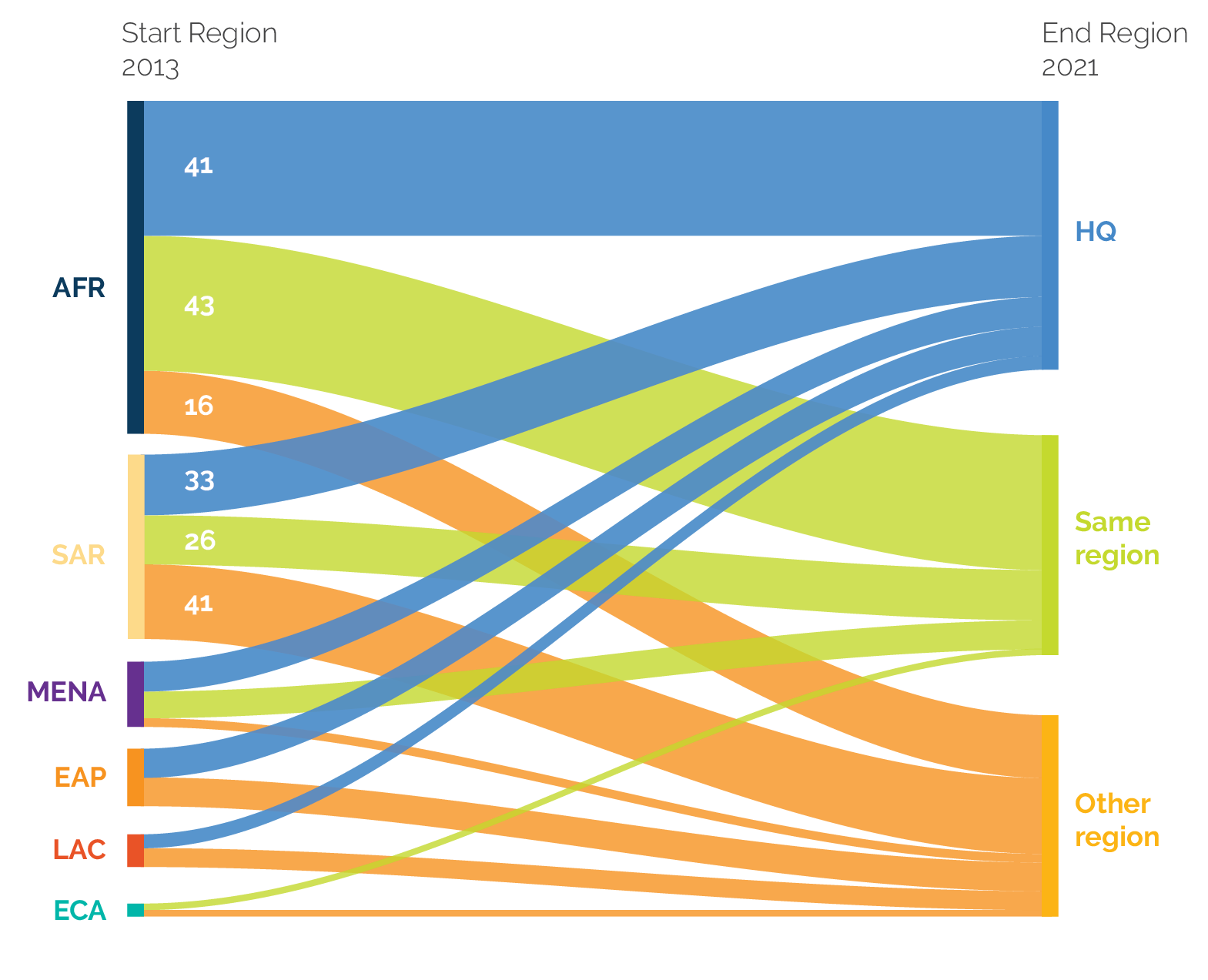

Countries in which a country director is based (CD countries) host significantly more professional staff than countries without a country director. Thirty-seven countries where country directors are located (cluster 1) had on average 22 professional GE+ staff (locally recruited and internationally recruited staff) in fiscal year 2020a but 57 countries with country directors located in a nearby country (cluster 2) had approximately four times fewer staff. Twenty-four countries that are served by nearby hubs or headquarters (cluster 3) had even fewer staff. CD countries do not necessarily have more projects per staff than non-CD countries—in CD countries, there are an average of 2.4 projects for every professional staff member, compared with approximately 4.5 projects in non-CD countries. In the same way, the lending volume per professional staff member is lower in CD countries than in non-CD countries (figure 4.1).

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: a. There is some variation within cluster 1 countries as well. Overall, large, single-country Country Management Units have more professional staff, especially locally recruited, than multicountry Country Management Units.

Figure 4.1. Professional Staff in Operations by Country Cluster

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: Cluster 1 = country director in a borrowing country—serving one country or multiple countries; cluster 2 = country director outside a borrowing country, located in a neighboring borrowing country; cluster 3 = country director outside a borrowing country, located in a hub (Part I country) or in Washington, DC, headquarters; FY = fiscal year.

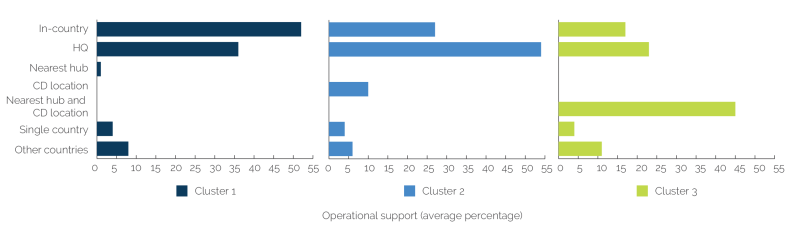

In multicountry CMUs, there may be an unintended human resource bias toward CD countries. Data analysis of the World Bank’s operational support (measured by the location of staff charging time to projects in case study countries) to the case study countries shows that this model may not be working the way it was intended (figure 4.2). For example, non-CD countries of CMUs (cluster 2) receive very little support from the CD country (only 10 percent) or from any other nearby office. Instead, more than half of the operational support to these countries still comes from headquarters, and only 27 percent of operational support comes from staff within the country. A vast majority of interviewees, including country managers and country directors, confirmed this resource allocation bias and awareness of the issue. Nearly all smaller non-CD countries revealed examples where an important project or an entire CPF business line was underachieved or delayed because the right expertise was not available in the country, and the country could not secure timely support from the CMU or a nearby hub. In one Europe and Central Asia Region country, the lack of a private sector expert with strong technical skills and global expertise hampered the country program’s private sector engagement as envisioned in the CPF. The case studies also demonstrate that IRS perform a wide range of other valuable tasks in the countries in which they are based that are not easily “programmed,” such as networking with the government, development partners, and civil society; developing new business; and mentoring LRS. It is much easier to carry out these less formal but important tasks if one is in the country than if one is in a nearby country. This suggests that although selected key staff are intended to be a CMU-wide resource, this often requires a deliberate effort from managers to make it happen.

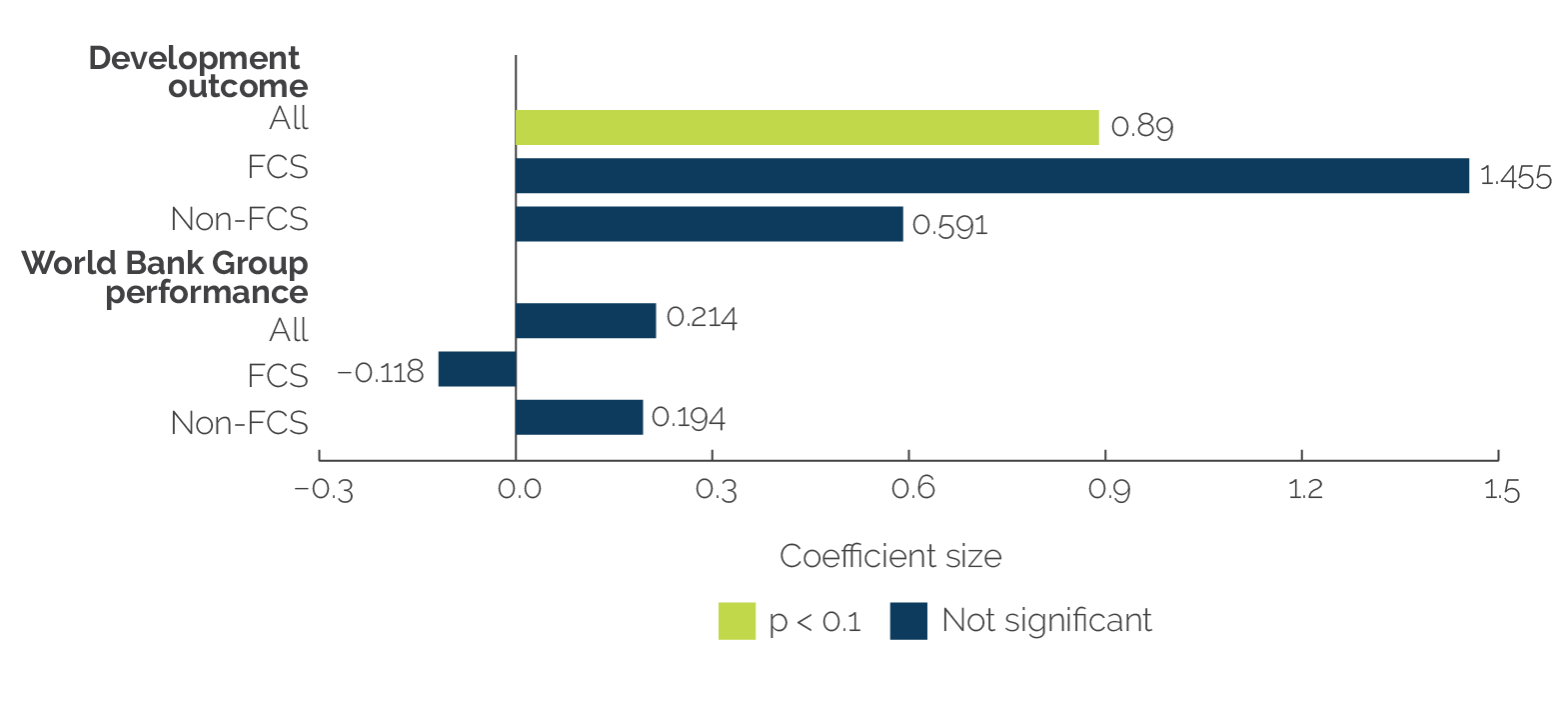

The availability of more professional staff in CD countries might contribute to better country program ratings in these countries, indicating the importance of having staff available in non-CD countries. A correlation analysis examined the effect of the country directors’ presence on the World Bank’s overall country program performance and the achievement of country development outcomes from FY10 to FY20.1 The analysis found that the country director’s field presence had a strong positive correlation with country program outcome ratings, measured by IEG’s CPF Completion and Learning Report Reviews. There is also a positive but nonsignificant correlation between the country director’s presence and the World Bank’s performance rating (figure 4.3). The positive influence a country director’s presence has on country program performance may suggest that the additional staff and resources, including more IRS, channeled to CD countries contribute to better outcomes.

Figure 4.2. Operational Support to 20 Case Study Countries by Cluster, Fiscal Years 2013–19

Source: Independent Evaluation Group analysis of World Bank staff time allocation data.

Note: Operational support refers to staff’s time allocation for a project measured by staff weeks. Cluster 1 = countries with country directors; cluster 2 = countries with country directors in a nearby country; cluster 3 = countries served by a nearby hub or headquarters. Nearest hub and country director locations are the same for cluster 3; “single country” refers to the country from which the case study country receives the most support; “other countries” refers to countries that provide operational support and that are not included in the rest of categories. For Cluster 1 countries, “in country” and “CD location” are the same. These data have some limitations; they exclude the support from financial management and procurement specialists, who charge their time to a central World Bank budget code rather than to projects. Program leaders’ time is also not fully allocated by projects, so it is possible that their support to neighboring countries is not fully reflected in these data. CD = country director; HQ = headquarters.

Figure 4.3. Association between Country Director Presence and World Bank Country Program Outcomes, Fiscal Years 2010–20

Source: Independent Evaluation Group’s analysis of human resources data and its rating database of Country Assistance Strategy Completion Report Reviews and Completion and Learning Report Reviews.

Note: Country program outcomes as measured by the length of the bar shows the coefficient size, and the color indicates coefficient significance Independent Evaluation Group development outcome and World Bank Group performance ratings are shown. The length of the bar indicates the coefficient size, and the color indicates coefficient significance. FCS = fragile and conflict-affected situations.

Decision-Making Inefficiencies

Locating practice managers in the field is less beneficial when most of their staff are not also in the field, when they are responsible for a wide geographic area, and when the time zone difference between headquarters and client countries is insignificant. World Bank management aims to move a large share of practice managers to the field in the medium term, bringing them closer to clients and field staff. However, this is most beneficial if most of the practice manager’s staff are in the field. A practice manager pointed out how being in West Africa vastly increased his interaction with field staff, especially LRS, who are mostly located in that Region. TTLs were able to connect with him for real-time advice, and he could be present on short notice for critical discussions. By contrast, another practice manager in West Africa with all but two of her direct reports in headquarters found it difficult to supervise headquarters staff from the field. The time zone difference between headquarters and client countries is another argument in favor of decentralizing practice managers. A country director in the South Asia Region said, “If the manager is based in Washington [, DC,] and the staff are 10 hours ahead, then you have a short window to get guidance, and also the turnaround time for clearances is longer.” The evaluation also found that decentralizing practice managers is less effective when they are responsible for large geographic areas because the vastness of the geographic scope they cover does not bring them much closer to clients. A headquarters-based practice manager said, “I oversee 25 countries. Even if I were in the field, travel in Africa is difficult, and I would not have time to see all our clients.” Practice managers for Europe and Central Asia and East Asia and Pacific expressed similar concerns about the large number of countries under their purview. The TTL survey also confirmed the importance of timely access to and decisions by managers as a key success factor for better client responsiveness (figure 3.7).

The widespread co-TTL model is less effective when the TTL with ADM responsibilities is not based in the client country. Designating country-based staff as co-TTLs is insufficient to ensure timely support during project implementation unless authority for decision-making is also devolved to them. The multivariate statistical analysis suggests that the presence of ADM TTLs in project countries is more beneficial to project ratings than the presence of other team members without decision-making authority (appendix B). As discussed in chapter 2, only 28 percent of ADM TTLs for lending projects that are in the field are located in their project’s country, on average. This share is even lower for FCS countries. Meanwhile, most of these projects have co-TTLs in the project country. Interviews show that all projects led from outside the country greatly benefit from having a co-TTL or qualified team member in the country to interact with clients, supervise projects, and keep up with the evolving local context. However, having a co-TTL without decision-making powers does not bring the same benefits to clients. A high-ranking client in Liberia said, “[World] Bank TTLs need to be in the field. Coming four times a year doesn’t really give a view of the needs in the country.” In Ukraine, a road safety project moved more slowly when the ADM TTL was in headquarters and a local junior-level co-TTL with no decision-making powers was in the field. The situation improved when the ADM TTL moved to the field, which made the project move faster and allowed the ADM TTL to empower her co-lead. Several World Bank staff felt there was no reason why co-TTLs, who are often locally recruited seasoned professionals, could not have ADM responsibilities. Other World Bank staff said that for the co-TTL model to work well, it needs to involve equal responsibility among the TTLs.

Global Knowledge Flow and Collaboration Challenges

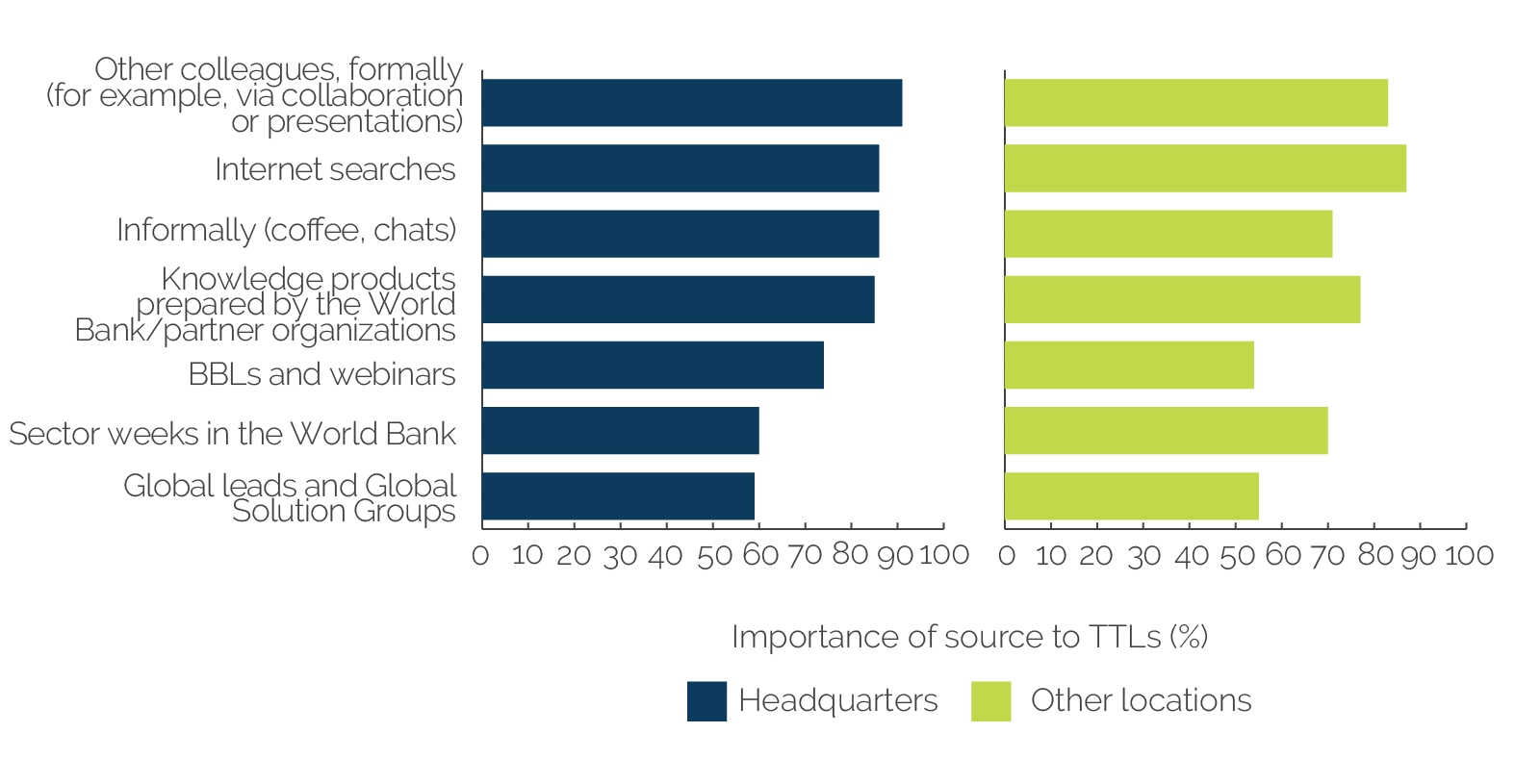

Decentralization and the World Bank’s internal knowledge management system impose inherent limitations on field staff’s access to formal global knowledge. Formal or explicit knowledge refers to reports, assessments, evaluations, learning events, or any number of official products. In interviews and surveys, World Bank staff expressed concern that decentralization and the organizational changes discussed in chapter 2 can pose a risk to knowledge flow across Regions. For example, most field-based TTLs found it difficult accessing global knowledge, with only 36 percent of those surveyed saying working in the field helped them access global knowledge. By contrast, 85 percent of headquarters-based TTLs felt their location helped them access global knowledge. This is partly because the World Bank’s knowledge generation system is largely in headquarters, where the largest number of sector staff are concentrated and where there is greater access to resources for learning events and analytical products. As a result, the World Bank’s knowledge largely comes from headquarters and is inevitably tailored more for headquarters staff. This is true despite this evaluation uncovering examples of decentralization bringing global knowledge and innovation to the field and generating valuable local knowledge from the field to inform World Bank strategies and operations. Interviews and the TTL survey also found that sector weeks, although highly valued, are infrequent; field staff have limited access to brown bag lunches because of connectivity issues or time zone differences; and some knowledge sharing mechanisms, such as Global Leads or Global Solution Groups, are ineffective.2 That said, the evaluation found that internet searches are one of the TTLs’ preferred sources of information, regardless of their location (figure 4.4), while many also noted the lack of sufficient time for learning as a constraint, regardless of their location.

Figure 4.4. Sources of Global Knowledge That Are Important or Somewhat Important for Task Team Leaders

Source: Independent Evaluation Group analysis of the TTL survey.

Note: Survey question: On a scale from 1 (unimportant) to 5 (important), please indicate how important the following sources of global knowledge were for your projects and other activities in fiscal year 2020, before the COVID-19 pandemic. BBL = brown bag lunch; TTL = task team leader.

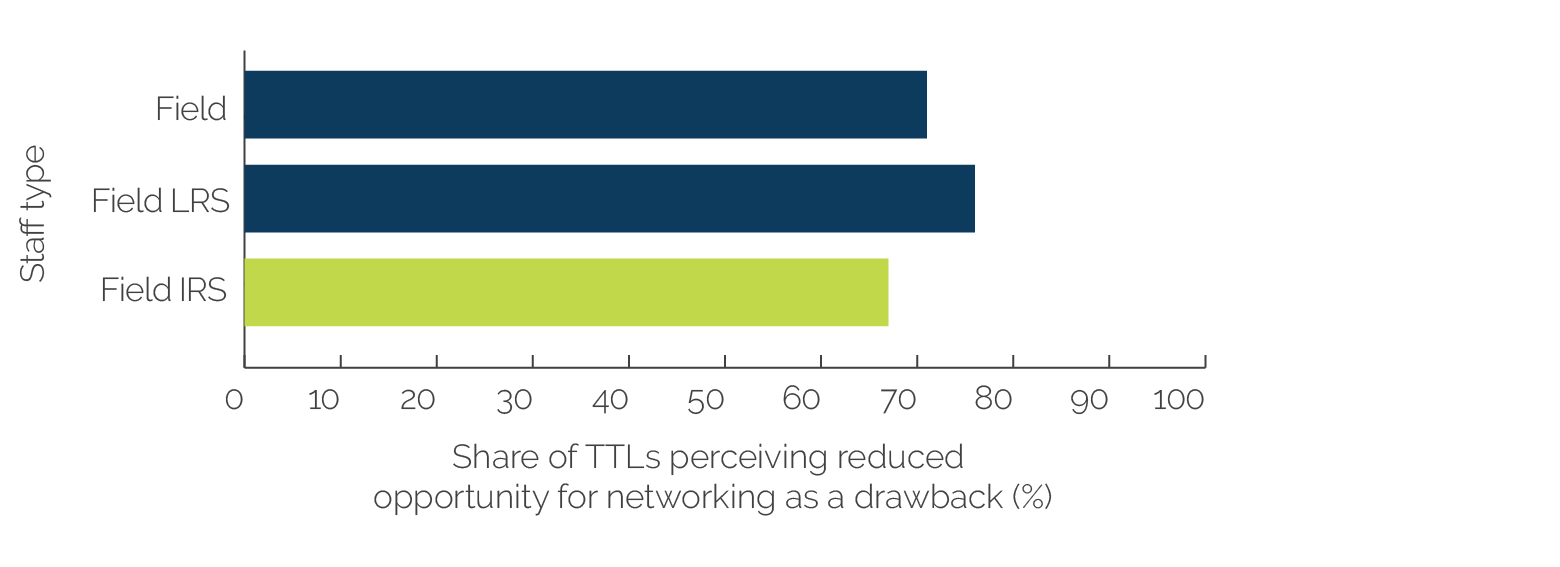

Decentralization makes it more difficult for field staff to acquire informal, or tacit, global knowledge and reduces global networking opportunities. Tacit knowledge is usually transferred through informal interactions. Interviews and the TTL survey show that informal interactions and idea exchanges among colleagues was one of staff’s most important sources for global knowledge. However, such interactions are limited for field-based staff, particularly LRS, because they are less globally mobile and have fewer networking opportunities than headquarters-based staff. According to the TTL survey, 71 percent of field-based TTLs, regardless of their recruitment type, felt that working in the field reduced the opportunity for networking. Reduced networking is particularly a problem for LRS TTLs, with 76 percent of them considering it a drawback of being in the field versus 67 percent of IRS (figure 4.5). Box 4.2 shows how staff in a country office can stay connected to the World Bank’s global network.

Figure 4.5. Task Team Leaders Perceiving Reduced Opportunity for Networking in a Country Office or Regional Hub

Source: Independent Evaluation Group analysis of the TTL survey.

Note: IRS = internationally recruited staff; LRS = locally recruited staff; TTL = task team leader.

Box 4.2. A Well-Connected Country Office: The Uganda Case Study

Uganda presents an interesting case study in how staff can be better connected to global networks in country offices, as opposed to in headquarters, hubs, or even the central Country Management Unit office. In Uganda, there is an unusually high number of internationally recruited and locally recruited staff in the country office and, contrary to the familiar refrain heard from staff in other country offices about the isolation from Global Practices (GPs), staff interviewed for the Uganda case seemed satisfied with their situation in this regard. Several factors seemed to contribute to this outcome, most of which could be replicated elsewhere. First, the relatively large size of the Uganda country office meant that there were at least two specialists per sector based in the country office. Second, the program leaders covering Uganda seem to have been especially conscientious about their role as the bridge between the GP and Country Management Unit, holding regular virtual team meetings with GP and Country Management Unit staff to share experiences and technical findings. Third, there were many high-level visits from both senior technical specialists and management, which allowed staff to connect with the broader institutional and GP-specific agendas. Fourth, the practice managers responsible for Uganda were strongly oriented toward nurturing staff potential and supporting staff’s professional development. And fifth, task team leaders in the Uganda country office were given opportunities to work across countries.

Source: Independent Evaluation Group, Uganda case study.

The human resource policy changes of 2020 may pose a risk to the flow of global knowledge by reducing the circulation of international staff between headquarters and the Regions and need to be carefully monitored. Several recent policy changes may have an impact on global knowledge flow and collaboration. As already noted in chapter 2, the remapping of sector staff to the Regions might reduce sector staff’s networking and opportunities to acquire work in other Regions. A practice manager said, “If you hire people directly to the field without them ever working in headquarters, they will not be able to network, and field staff will gradually work more in [R]egional silos. We know each other from cross-practices, but these connections will gradually disappear over the years. With the suggested Global Footprint Plan, how do you ensure rotation, how do you get to another [R]egion if they don’t know you?” A country director noted, “As more and more people are pushed further into the field, where they stay from 4 to 8 years, how will the flow of knowledge across the [R]egions be maintained? There were already challenges under the Global Practices model. How does cross-fertilization happen? What is the new model? It is important to think through this model in this process to preserve our global nature, so we don’t mimic regional development banks.” The new Career Development and Mobility Framework (FY21), which aims to improve the mobility of IRS by introducing a more structured approach to IRS rotation, also may inadvertently weaken the global knowledge flow. The framework is likely to reduce the flow of professional (sector) staff between headquarters and the Regions because the new approach does not guarantee a return to headquarters. Given the critical role of headquarters in generation and flow of knowledge, the lack of systematic circulation of IRS to Washington, DC, where GPs are located, might further fragment global knowledge. Likewise, in IFC, an increased decentralization raised concerns over Regional silos and the deterioration in global knowledge and sharing of global experience. IFC professional staff in the field have shorter experience at IFC than their headquarters peers, and this likely reduces opportunities for junior staff in the field to learn from senior staff because of high staff turnover.

Formal or explicit knowledge generated by field staff is often less valued and less frequently curated for global use than headquarters-generated knowledge. One of decentralization’s potential benefits is that it would help integrate local knowledge into the World Bank’s global knowledge network and inform World Bank strategies and operations. This is difficult to measure objectively, but there is a strong perception among World Bank staff that knowledge produced by field staff, such as country-focused reports and analytical studies, is less appreciated, recognized, and shared outside of the country or Region in which it was produced. A program leader in a large LMIC country said, “Every country unit is doing work on productivity, for example. Yet, it is never compiled. The chief economist is more interested in doing cutting-edge research than policy-relevant technical work. We need to bring these two together.” Field-based TTLs see this as an institution-wide problem that undervalues formal knowledge generated in the field. In the TTL survey, only 44 percent of field-based TTLs said their location helped them generate global knowledge, but 82 percent of headquarters-based TTLs said the same. In the view of many staff, the larger diagnostic products produced in headquarters have high visibility, despite often not being relevant to country programs, but in-country products that can have a profound influence on government policy and other operational work remain under the radar of headquarters units responsible for knowledge management and get less recognition. This low visibility strongly undermines chapter 3’s finding that the World Bank’s country-focused analytical products are a powerful conduit for influencing policy changes in client countries.

Decentralization can dilute the World Bank’s organizational cohesiveness and shared corporate culture. Organizational culture is defined as a set of beliefs, values, and assumptions that are shared by members of an organization (Schein 1985). Ample literature shows the importance of organizational culture on organizational effectiveness (Barney 1986; Schraeder and Self 2003; Bulent and Adnan 2009). Schneider (1988) defined corporate culture as the “glue” that holds organizations together by providing cohesiveness and coherence among the parts. This evaluation found that staff, particularly practice managers, are concerned about the potential negative impacts of decentralization on the World Bank’s corporate culture. The concern extends mainly to LRS in general and IRS who carry out several consecutive field assignments because they have limited exposure to headquarters. More than half of LRS TTLs were concerned about their limited access to corporate culture and global knowledge. The increasing trend in the World Bank to hire TCNs on indefinite assignments in the field is likely to pose similar risks. In fact, IFC’s more extensive experience with TCNs shows the difficulties in familiarizing them with IFC’s mission and headquarters’ services. The IFC decentralization experience also shows that the greater autonomy given to country programs and staff’s detachment from corporate culture corroded common quality standards.

LRS face certain in-country pressures that IRS and managers can effectively mitigate. LRS often must walk a fine line between becoming a trusted confidante of the government, civil society, and local development partners and remaining neutral when dealing with these local partners, many of whom may be friends or former colleagues. Maintaining impartiality is important for LRS when providing healthy criticism or conveying tough messages to clients. This is not a World Bank–specific issue but an inherent risk for any large, decentralized organization. This challenge is particularly poignant in countries with highly charged political environments. One interviewee from a small FCS country said that when LRS oppose local counterparts, “they are scared for their life and the safety of their family.” Many interviewees suggested that one way to relieve this pressure on local staff is to have international staff play the role of an “honest broker,” or “bad cop” to the LRS’s “good cop” in sensitive interactions with partners. In this context, it is important for IRS to not undermine LRS and make the World Bank’s reliance on the LRS’s judgment clear to the client.

Decentralization might reduce collaboration among GPs by dispersing sector staff in the field, but this risk is mitigated when different sector staff are co-located in the same field office. The TTL survey showed that 16 percent more headquarters-based TTLs than field-based TTLs felt that their location helped or greatly helped them with cross-GP collaboration (figure 4.6). According to interviews, the headquarters’ centralized structure also enhanced the collaboration among managers. A practice manager in Africa said, “In [headquarters], all GPs are present, so you can have more day-to-day interactions. Most Practice Managers and Regional Directors are still in [Washington,] DC, so connectivity [there] is better among management. Decentralization limits this connectivity, so there are some downsides.” For the same reasons, however, cross-GP collaboration can also work when staff from different GPs are co-located in the same physical space. A TTL based in the Romania country office, which has a large staff presence, said, “Collaboration works better because we have staff from different GPs in the field,” and another TTL from Argentina said, “Cross-GP work is so much more effective in the country when technical GP staff are sitting in one place.” A TTL in Vietnam said, “The rapport within the country team in the office brings multiple GPs together to work collectively. In [Washington,] DC, at times this cohesion falls apart.”

Figure 4.6. Extent to Which Task Team Leaders’ Location Helps or Hinders Collaboration with Colleagues from Other Global Practices

Source: Independent Evaluation Group analysis of the TTL survey.

Note: HQ = headquarters; TTL = task team leader.

Career Development Challenges

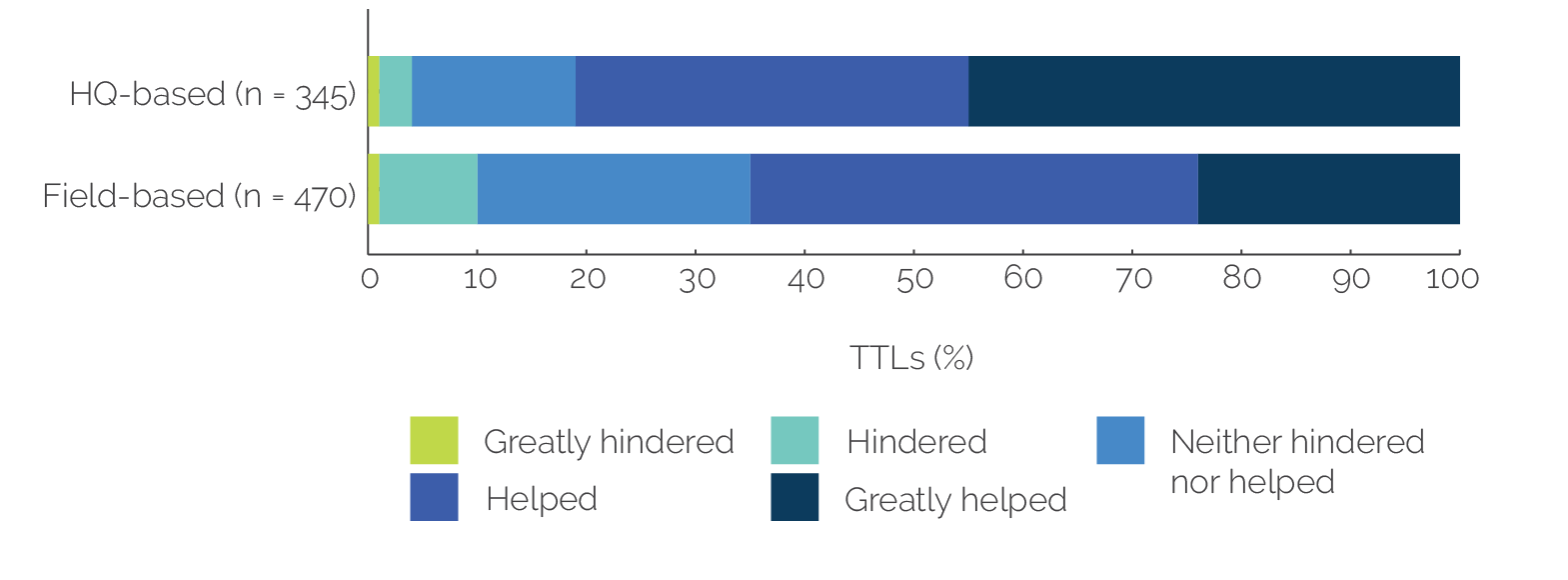

There are strong and widespread perceptions among World Bank staff that field postings inhibit career progression. Seventy-one percent of field-based and 56 percent of headquarters-based respondents in the TTL survey thought that being in the field hampers the “networking and visibility needed for career development.” Being in the field also makes finding the next job assignment more difficult (figure 4.7). These perceptions are also confirmed in interviews, where staff frequently noted that field assignments may result in fewer career growth opportunities because of lack of access to managers and sector peers. Interviews also show that staff commonly believe they will diminish their prospects of getting a position at headquarters if they accept a position in “difficult” field locations, becoming what they call “field nomads.”

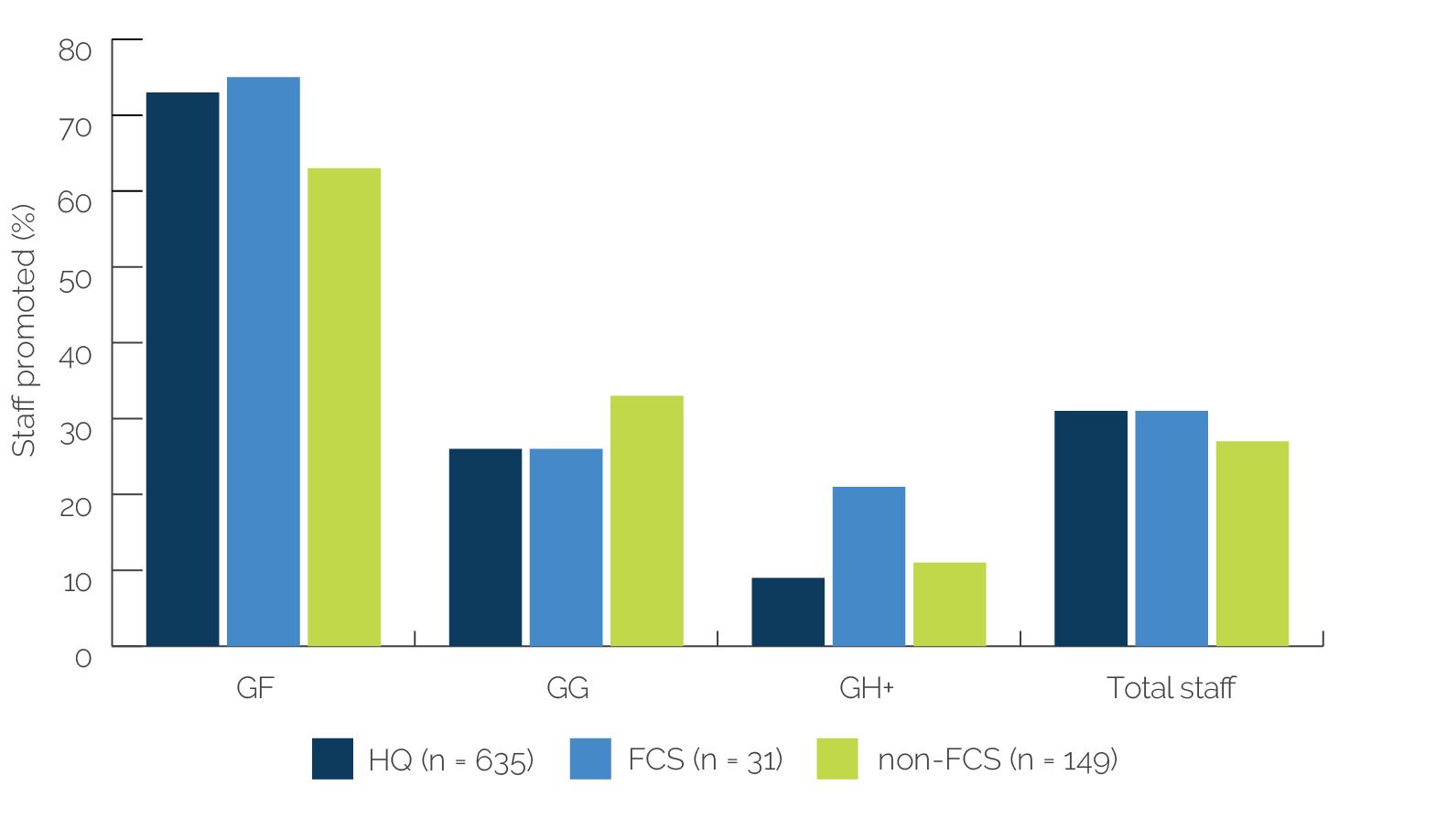

Despite such common misperceptions, the promotion rates were higher for field-based staff than for headquarters staff. The quantitative evidence over the evaluation period shows that promotion rates for field-based staff in both FCS and non-FCS countries at levels GG and above, encompassing most of the IRS staff in the field, is generally higher than for headquarters-based staff at the same levels. In fact, only GF-level staff at headquarters had a higher promotion rate than field-based staff in non-FCS countries, though these results may be skewed since GF staff are disproportionately present at headquarters (nearly 90 percent); even so, GF staff in FCS countries still had higher promotion rates than GF staff at headquarters (figure 4.8).

Figure 4.7. Perceived Drawbacks among Staff of Being in the Field

Source: Independent Evaluation Group analysis of the TTL survey.

Note: Survey question: Please indicate what you perceive to be drawbacks of being based in a country office or regional hub.

Figure 4.8. Promotion Rates by Staff Grade, Fiscal Years 2013–21

Source: Independent Evaluation Group analysis of human resources data.

Note: FCS = fragile and conflict-affected situation; HQ = headquarters.

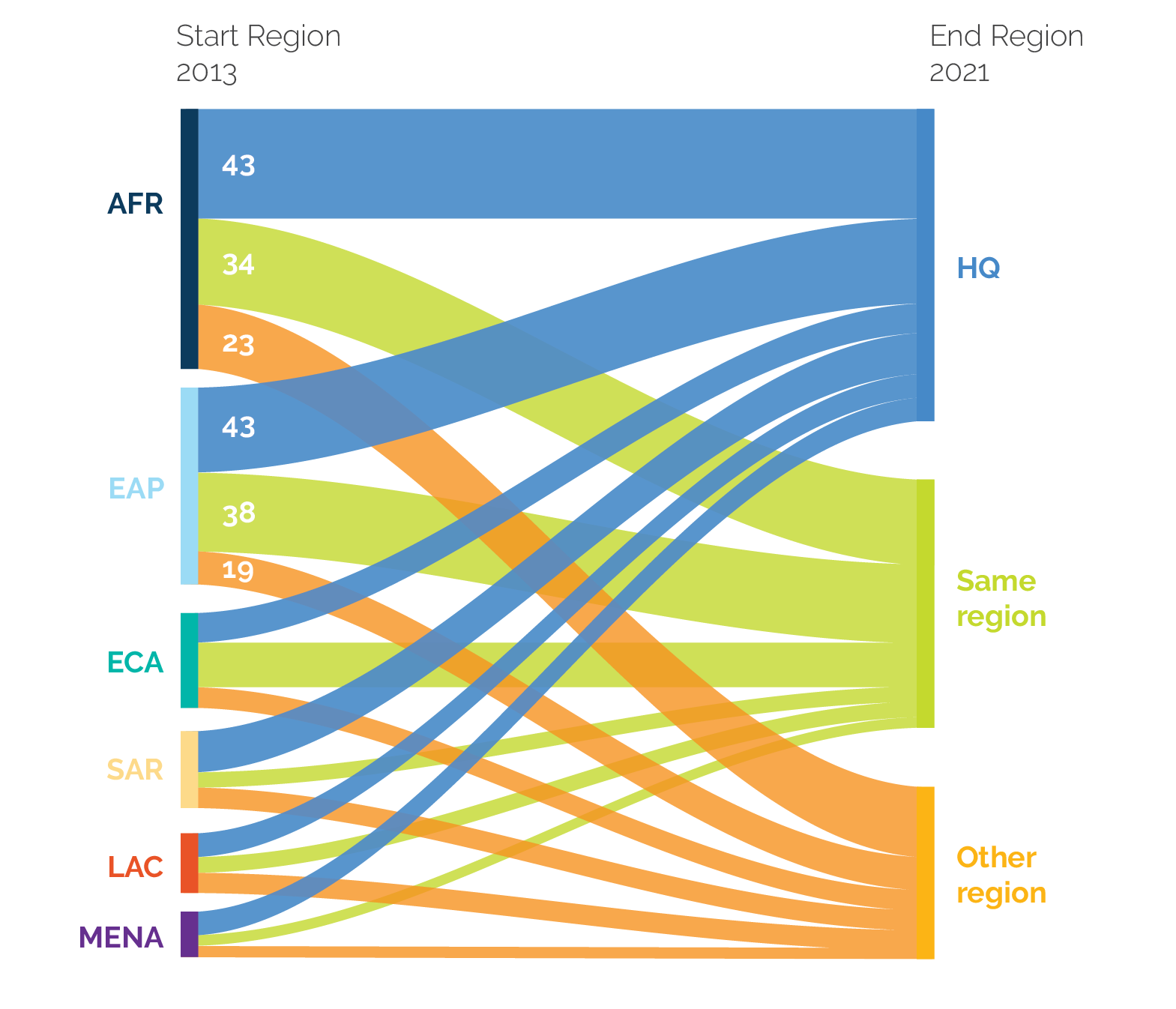

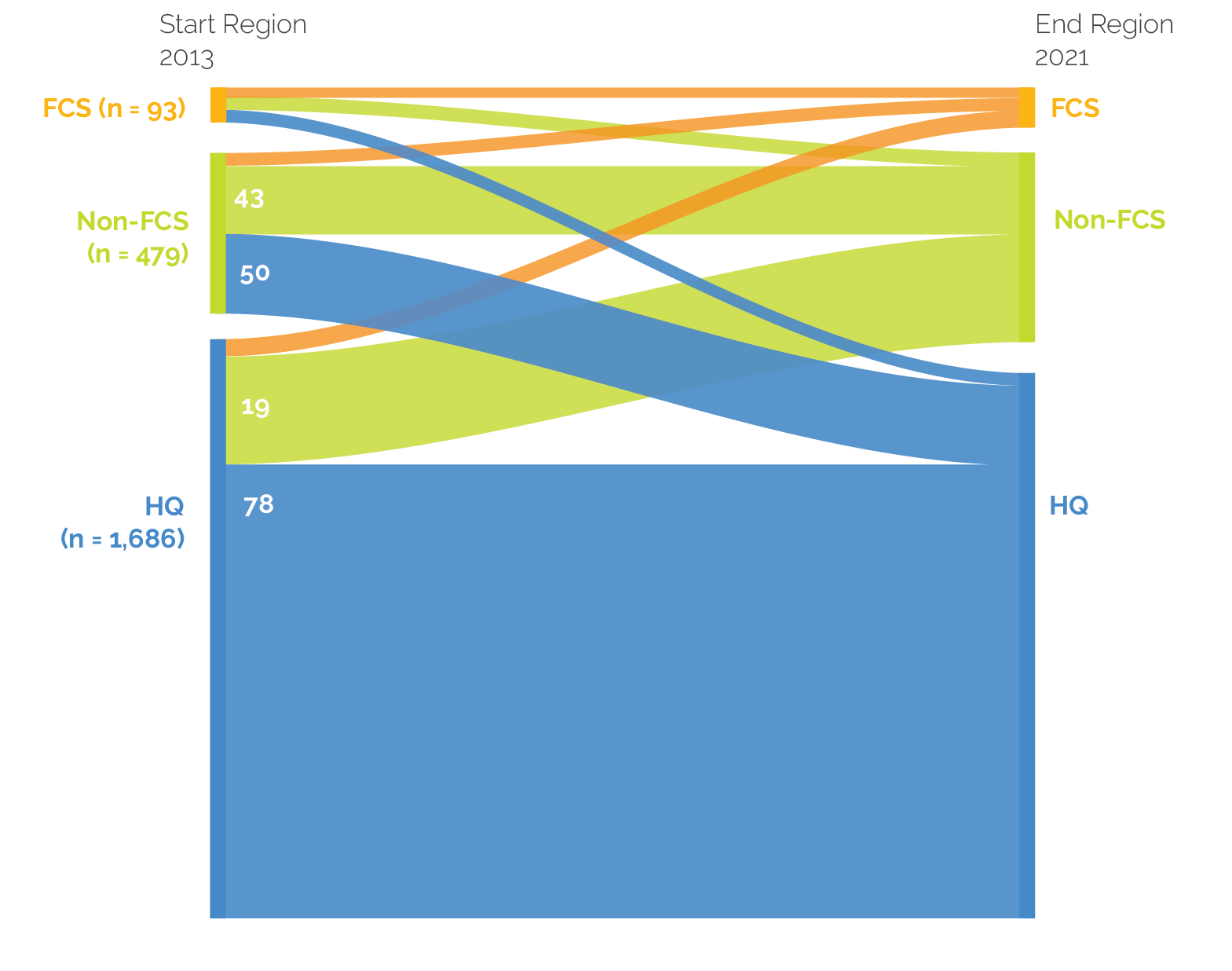

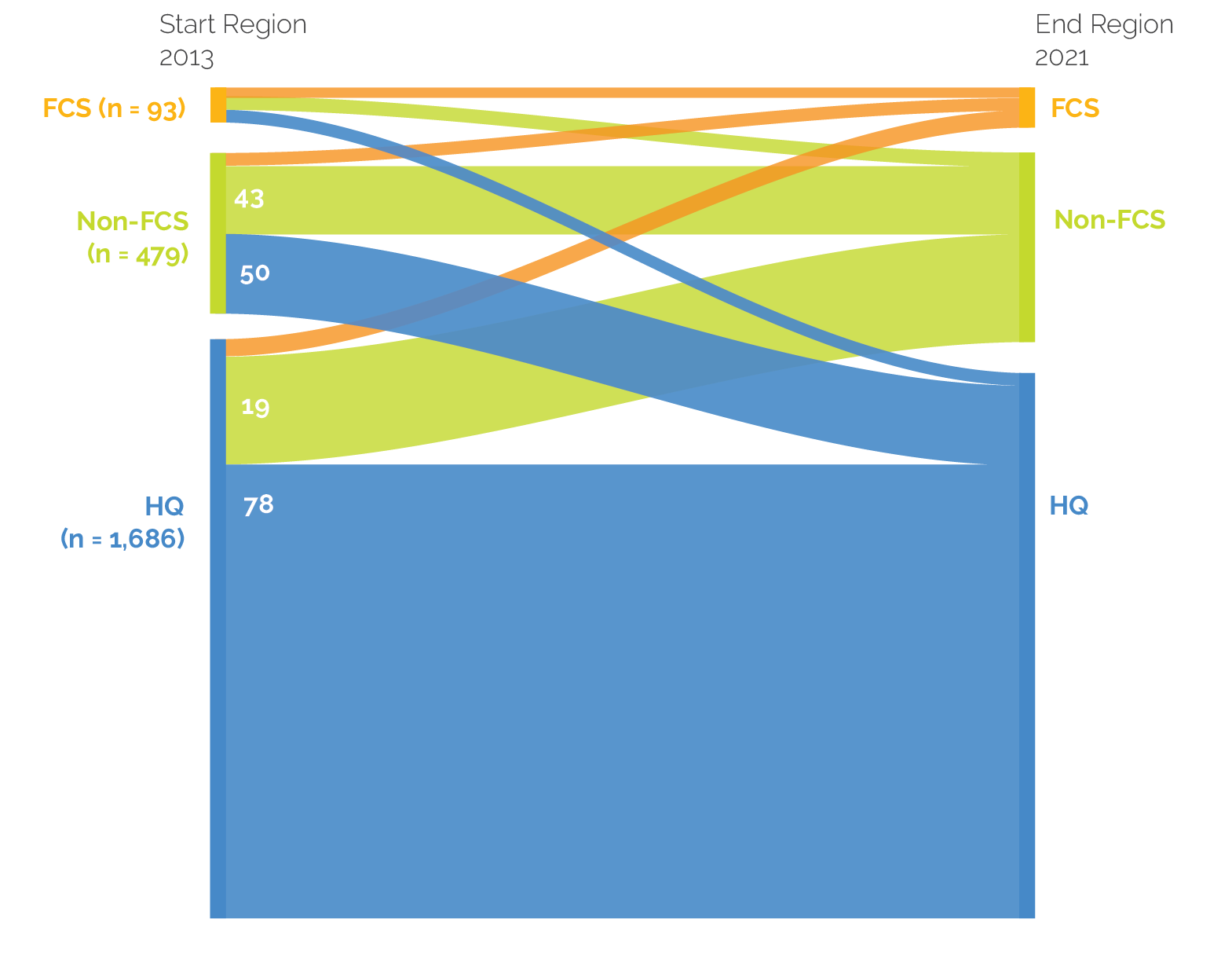

The movement of staff between headquarters and the Regions is also fluid, dispelling the strong perception that staff who move to field positions remain in field positions, especially in Africa and FCS locations. Forty-one percent of IRS based in FCS locations in Africa in FY13 moved to headquarters for their next assignment by FY21 (figure 4.10). This is 6 percent lower than in FY19 but still higher compared with the movement of IRS to headquarters from FCS locations in other Regions. Forty-three percent of IRS in Africa in FCS locations remained in the same Region, while only 34 percent of IRS who were in non-FCS countries in Africa in FY13 remained in the same Region in FY21. Africa and East Asia and Pacific Region have the largest share of staff moving to headquarters from non-FCS locations (figure 4.9). Moreover, it was the Europe and Central Asia and East Asia and Pacific Regions, not Africa, that had the highest rates of staff continuity in non-FCS locations among the Regions. In addition, figure 4.11 shows that the results in FCS countries in all Regions are similar, with a large share of staff in FCS countries in FY13 moving to headquarters or non-FCS locations rather than FCS locations by FY21. That said, IRS staff in FCS countries were, in fact, more likely to remain in their Region than staff initially located in non-FCS countries (figure 4.10).

Figure 4.9. Movement (Job Change) of Internationally Recruited Staff in Non-FCS Countries by Region, Fiscal Years 2013–21 (%)

Source: Independent Evaluation Group analysis of human resources data.

Note: AFR = Africa; EAP = East Asia and Pacific; ECA = Europe and Central Asia; FCS = fragile and conflict-affected situations; HQ = headquarters; LAC = Latin America and the Caribbean; MENA = Middle East and North Africa; SAR = South Asia.

Attracting international staff with strong technical and operational skills and the right mind-set to field posts is difficult in many FCS and lower-income countries. The demand is high for IRS with strong technical or operational skills and the right attitude and people skills for field posts. However, these staff have limited interest in working in such countries because these posts have low visibility, are perceived to have limited prospects for career growth, and have a lower quality of life. Country directors and country managers for FCS countries reported that few high-quality staff applied for posted positions through the batch recruitment process and that they needed to proactively reach out to these candidates to encourage them to apply. By comparison, job advertisements for posts in some large middle-income countries attracted more than 50 qualified applicants. The lack of high-quality field staff can have negative consequences on a country program’s performance. For instance, according to IEG’s evaluation of knowledge flow and collaboration, country managers in smaller countries believed that inexperienced TTLs gave bad advice to clients and were unfamiliar with the World Bank’s internal policies and procedures (World Bank 2019b, 41).

Figure 4.10. Job Change of Internationally Recruited Staff in FCS Countries by Region, Fiscal Years 2013–21 (%)

Source: Independent Evaluation Group analysis of human resources data.

Note: AFR = Africa; EAP = East Asia and Pacific; ECA = Europe and Central Asia; FCS = fragile and conflict-affected situations; HQ = headquarters; LAC = Latin America and the Caribbean; MENA = Middle East and North Africa; SAR = South Asia.

Figure 4.11. Movement (Job Change) of Internationally Recruited Staff between FCS and Non-FCS Countries and Headquarters (%)

Source: Independent Evaluation Group analysis of human resources data.

Note: Figure shows staff who changed location and title; location and division; or location, division, and title, between 2013 and 2021. FCS = fragile and conflict-affected situation; HQ = headquarters.

Some recent human resources policies may further erode the incentives for qualified IRS to move to the field. One such policy from 2020 makes country manager positions “ungraded,” meaning that accepting the role may not come with a promotion. The aim of this move was to expand the eligibility for country manager positions to staff with a G grade level for “less complex” countries. However, this may put a staff with a higher-grade under the supervision of a lower-grade manager, discouraging higher-grade staff from applying to field positions. Placing a limit on promotions to lead specialist (H level) is another corporate policy that demotivates high-performing and qualified staff from applying for difficult assignments. A former country director for an FCS country said, “We’re pushing decentralization, but we have made it difficult for staff. In FCV countries, it is difficult to bring family. So, what is the incentive system for staff? We are cutting H-level positions and offer no real pay increases, no promotions; positions are downgraded. We are not providing the incentives for people to decentralize.” IFC also found that motivating staff to work in FCS countries, even when based in the hubs, was challenging. Although there is a strong push to grow IFC’s business in FCS countries, there were no performance incentives to match this (appendix D). IFC is attempting to rectify this by adopting FCS and IDA-specific performance indicators in its Corporate Scorecard. IFC’s experience in this area could point to avenues for the World Bank to pursue.

Many IRS feel that the World Bank’s support to families moving to the field, especially in poorer or FCS countries, must be improved. Studies in human resources and organizational performance show that inadequate repatriation practices and the insufficient adjustment of a staff member’s family to a new location can lead to unsatisfactory performance by the staff member and even their departure from post.3 Fifty-four percent of IRS TTLs considered reduced professional opportunities for spouses and partners as the main drawback of decentralization. A recent GLOBE workplace climate survey (2020) and interviews also highlighted the mobility and field career challenges of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex, and queer staff that need to be addressed as well. IRS in interviews said the World Bank did not help them enough in identifying work opportunities for spouses, finding good housing options, or providing logistical and legal guidance when moving to new locations. For example, nearly all the Kathmandu-based IRS interviewed for the Nepal country case study indicated there was no system to support staff that moved there, despite the difficult living conditions in the country. As a result, newly arrived IRS said they had to find their own housing, access utilities, and establish medical care for their families and education for their children, all while maintaining a full-time work schedule. These challenges have been amplified by the COVID-19 crisis, in which good health care and clear direction to moving staff are essential for protecting staff’s health.

The professional growth and career progression opportunities for senior LRS in the field are limited. Since the late 1990s, LRS have made up the core staff of most World Bank country offices. Most of them have worked in World Bank offices for many years and gained seniority and substantial experience during that time. A handful of LRS transition into IRS positions and move out of the country, but for most who want to remain in the country, the World Bank offers few options for professional growth. An IRS in Vietnam said, “We need to find ways to help the career development of local staff who do not want to become IRS because they don’t want to leave their country. They need to be able to diversify their programs and gain experience and seniority.” LRS’s limited career development opportunities are aggravated by fewer networking opportunities and less access to managers, who are located in hubs or headquarters. A Somalia program leader said, “If you do not give LRS opportunities to grow, you dissipate your human capital and de-skill them over time.” The evaluation found that international staff and managers almost unanimously supported providing structured professional and career growth opportunities for their local colleagues. In this spirit, box 4.3 shows how exposing talented LRS to cross-country experiences can be beneficial for both the institution and the staff member’s career.

Box 4.3. Effect of Exposing LRS to Cross-Country Experiences

When the World Bank’s office closed in the Republic of Yemen in 2015 because of the political crisis, the World Bank relocated four of its Yemeni staff to Amman, Jordan. Three of these staff had previously worked only on operations in the Republic of Yemen, but one had Regional experience. By fiscal year 2020, only the staff with the Regional operational experience was selected to lead operations in Jordan, and the others remained in supporting roles. It was this staff’s Regional experience that qualified him for this leadership position.

Source: Independent Evaluation Group, Jordan case study.

The mentoring of field-based LRS does not happen regularly unless done intentionally and proactively. In headquarters, staff have regular interactions with managers and senior technical specialists, so mentoring occurs naturally. In field offices, however, there are fewer opportunities for this type of informal interaction and mentoring, so country programs must make specific, intentional efforts to do so. IFC’s experience suggests that relying on informal mentoring in country offices is unlikely to meet the needs of new and junior staff. The Vietnam country office, for example, has put in place formal mentoring programs to ensure that LRS can grow professionally. Mentoring is particularly important for new local hires in country offices to ensure they understand the World Bank’s mission and their role in supporting it. Country managers, program leaders, practice managers, and experienced IRS can facilitate this by being proactive in ensuring that junior staff and LRS can turn to them for advice and guidance. In interviews for the Afghanistan and Armenia case studies, a number of country directors and managers proudly shared experiences of helping local staff successfully engage in Regional opportunities or successfully compete for IRS positions by providing them with guidance, feedback, training, and opportunities to do cross-support. The consensus in interviews and the TTL survey was that mentoring works best when it is done among field-based staff in the same office, particularly in FCS countries, where missions tend to be short and intense and offer fewer opportunities for visiting staff to mentor. In Myanmar, for example, the tight labor market means that few local staff have much experience; therefore, mentorship helps build needed capacity.

Overall, despite the perceived drawbacks and challenges associated with field assignments, field-based staff often have high job satisfaction. The World Bank’s annual staff surveys show that field-based staff tend to be more satisfied than headquarters staff with their work and authorizing environment. The interviews for the country case studies also reflected field-based staff’s high personal satisfaction with work. An IRS in Hanoi said, “Perhaps most important of all, it is exciting to be in the field—you just have much more enthusiasm for the job.” Another particular benefit of being located in the field is that mission travel, although more frequent, tends to be of shorter duration, leaving more time for family and social demands. Sixty percent of field-based TTLs indicated that professional travel did not impose a burden on their personal lives, compared with only 20 percent of headquarters-based staff.

- See appendix A for detailed results from the correlation analysis and its limitations. The analysis replicates the analysis carried out for the Independent Evaluation Group’s 2010 Results and Performance of the World Bank Group, which looked at the correlation between country director location and country program outcomes (World Bank 2010b).

- Sector learning weeks or forums are a weeklong on-site annual gatherings of professional staff, international and local affilitated with a Global Practice, for trainings, knowledge exchange, and networking. Sector weeks were usually held in Washington, DC.

- These studies found that a spouse’s lack of a social network, increased financial dependency, and lack of status were the main reasons for spousal dissatisfaction. Expatriate success could be improved by emphasizing the importance of the family for the position and providing support systems for the spouse. See, for example, Stoner, Aram, and Rubin (1972).