The International Development Association's Sustainable Development Finance Policy

Chapter 3 | Assessing Sustainable Development Finance Policy Design

The evaluation of SDFP’s design focuses on the extent to which the SDFP as designed and implemented to date addresses the origins of the rise in debt stress in IDA-eligible countries over the past decade. The assessment is undertaken with respect to four dimensions:

- Country coverage

- Debt coverage

- Incentive structure for actions by borrowers and creditors

- Relevance of country-specific PPA

The assessment also considers the monitoring and evaluation framework in place by which to assess progress toward the policy’s objectives.

Country Coverage

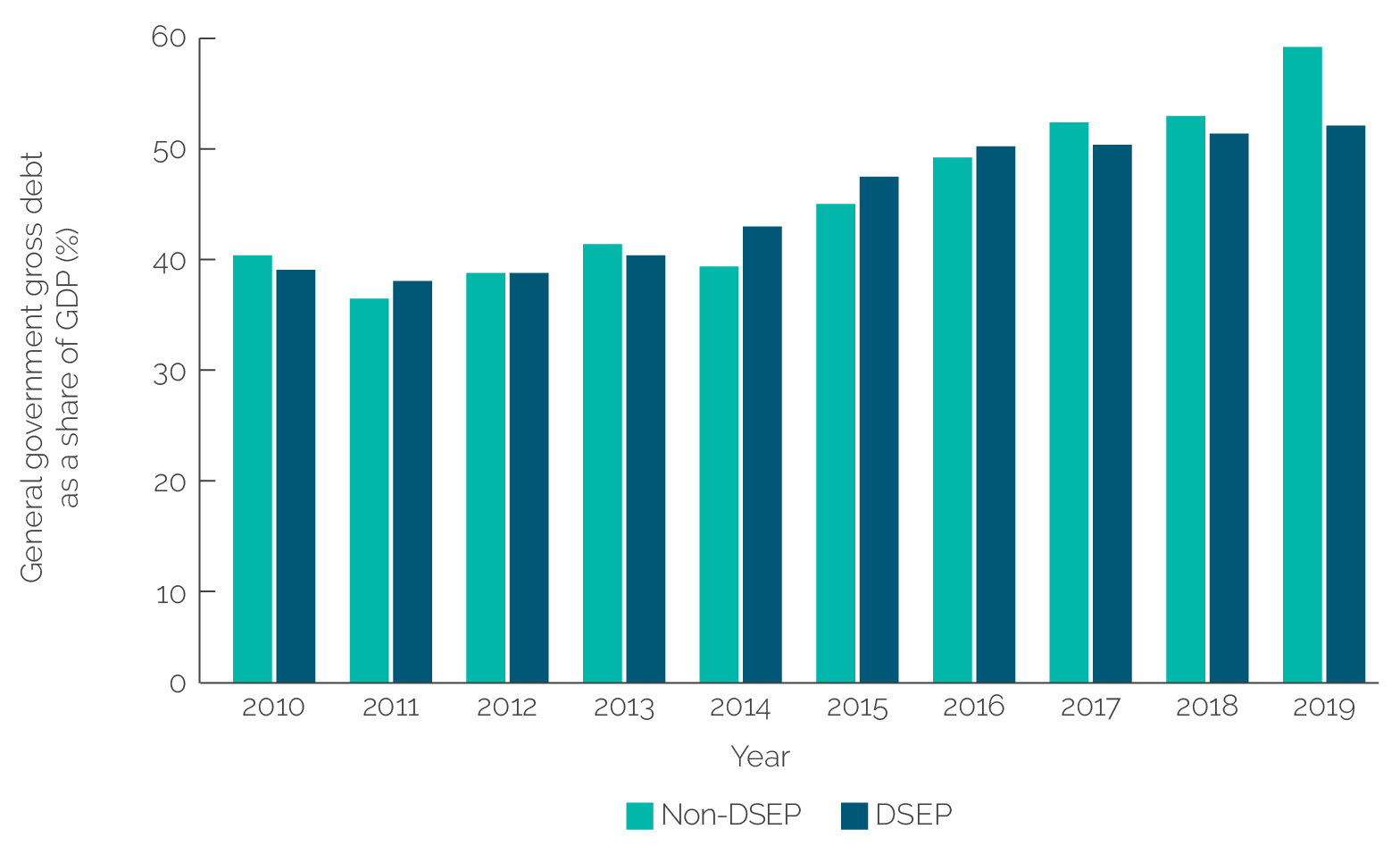

The SDFP expands the NCBP’s country coverage to a larger number of IDA-eligible countries facing risks of debt distress. Although the NCBP applied only to post-MDRI and grant-eligible IDA-only countries, the SDFP applies to all IDA-eligible countries. This expands the scope of the policy from 44 countries (under the NCBP) to 74 countries.1 Regarding the composition of countries covered, of the 40 (of 74) IDA-eligible countries determined to be at high risk of debt distress (or in debt distress) in FY21, the SDFP covers almost half (17) that the NCBP would not have covered. However, only a subset of SDFP countries implement policy actions under the DSEP. Fifty-five countries are required to implement PPAs under the SDFP, 11 more than were covered under the NCBP (figure 3.1).

The policy guidelines identify three categories of countries that are not required to agree to and implement PPAs: (i) countries at low risk of debt distress according to the Debt Sustainability Framework for LICs (LIC DSF) and countries under the Debt Sustainability Analysis for Market Access Countries (MAC DSA) for which management determines that debt vulnerabilities are limited;2 (ii) countries in nonaccrual status with the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development and IDA;3 and (iii) countries that are eligible for IDA’s Remaining Engaged during Conflict Allocation.4

Figure 3.1. Sustainable Development Finance Policy versus Non-Concessional Borrowing Policy by Country’s Risk of Debt Distress, FY21

Source: Independent Evaluation Group compilation based on International Development Association performance and policy action database.

Note: FY = fiscal year; MAC DSA = Debt Sustainability Analysis for Market Access Countries; NCBP = Non-Concessional Borrowing Policy; SDFP = Sustainable Development Finance Policy.

Screening countries for risk of debt stress relies on the World Bank–IMF debt sustainability analysis (DSA). The SDFP screens all IDA-eligible countries. IDA-only countries assessed to be at medium or high risk of debt distress or in debt distress, according to the LIC DSF, fall under the DSEP and are required to undertake PPA. IDA blend countries are evaluated using the MAC DSA. Countries found to breach the vulnerability thresholds for debt, gross financing needs, or debt profile indicators are subject to implementing PPAs under the DSEP. The LIC DSF (box 3.1) and MAC DSA draw heavily on the country’s past performance and projected outlook for real growth, international reserves coverage, remittance inflows, the state of the global environment, and the World Bank’s Country Policy and Institutional Assessment index. Different indicative thresholds for debt burdens are used depending on the country’s assessed debt-carrying capacity.

Box 3.1. Debt Sustainability Framework for Low-Income Countries

The Debt Sustainability Framework for Low-Income Countries (LIC DSF) applies to low-income countries that have substantially long-maturity debt with terms that are below market terms rates (concessional debt) or to countries that are eligible for the World Bank’s International Development Association grants.

The LIC DSF is the main tool to assess risks to debt sustainability in low-income countries. The framework classifies countries based on their assessed debt-carrying capacity, estimates threshold levels for selected debt burden indicators, evaluates baseline projections and stress test scenarios relative to these thresholds, and then combines indicative rules and staff judgment to assign risk ratings of debt distress.

First introduced in 2005, the LIC DSF has been subject to a comprehensive review every five years. The most recently revised LIC DSF became operational in 2018.

Source: World Bank Debt and Fiscal Risks Toolkit (https://www.worldbank.org/en/programs/debt-toolkit/dsf).

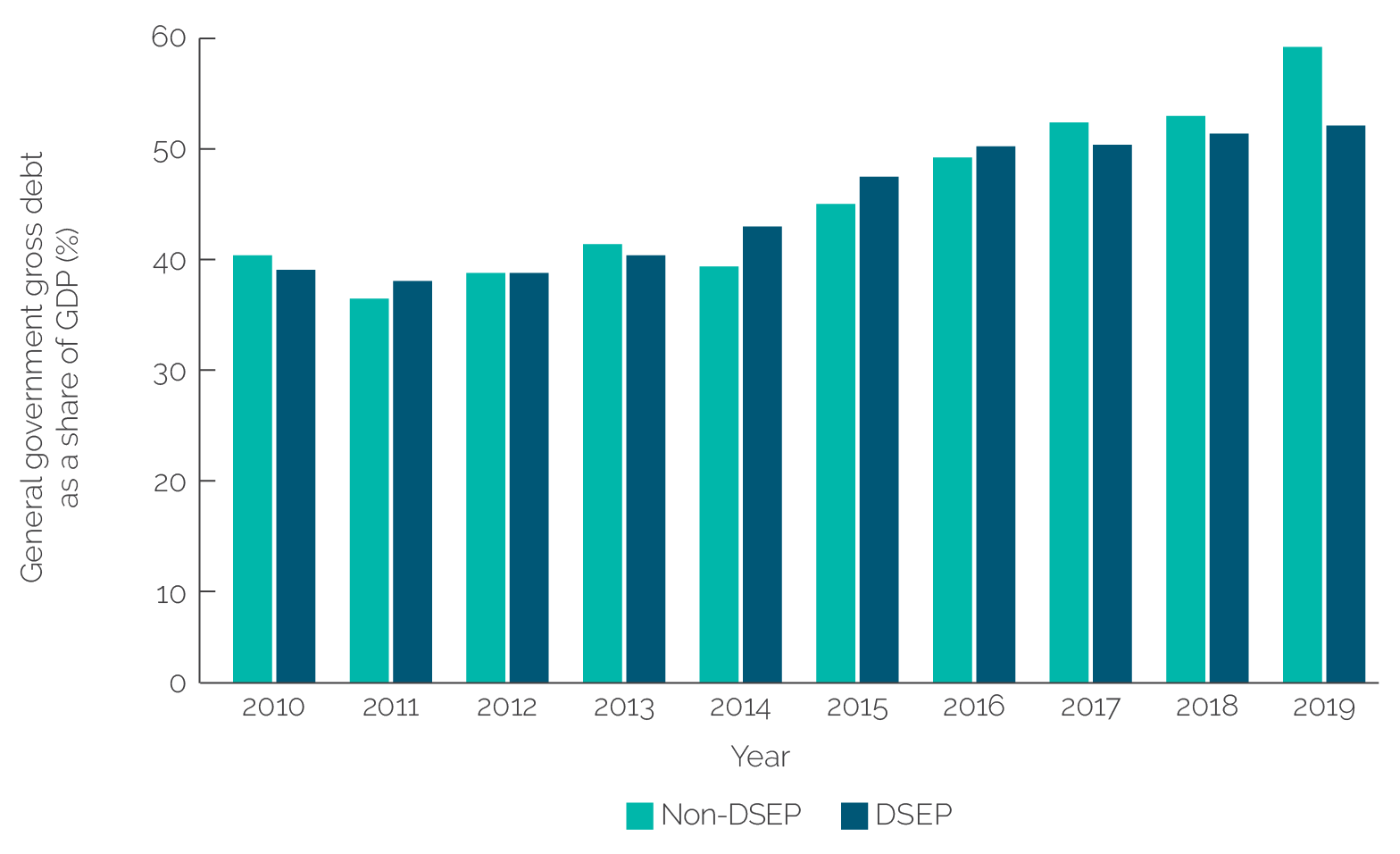

The pattern of debt accumulation is largely the same for IDA-eligible countries covered and not covered by the DSEP. The trajectory of debt-to-GDP across DSEP versus non-DSEP countries is nearly identical, and since 2017, debt as a share of GDP was, on average, higher in non-DSEP economies (figure 3.2). The DSA that underpins the LIC DSF is driven to a significant extent by assumptions about the future, many of which can change quickly because of unanticipated shocks or policy shifts (for example, growth outlook). Moreover, DSA growth assumptions have tended to have an optimistic bias, with downside risks often underestimated, particularly regarding contingent liabilities of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) or in assessing the potential impact of a compounding of vulnerabilities (World Bank, forthcoming). World Bank management has recognized this and is in the process of improving DSAs’ governance and contestability.

The underlying logic of not applying the DSEP to countries at low risk of debt distress rests on an implicit assumption that low risk equates to sustainable development financing practices. However, experience over the past decade shows that countries at low risk of debt distress can shift into higher levels of risk in a relatively short time. In fact, one-third of the countries that experienced an elevation in their risk of debt distress over the past decade experienced a two-level deterioration in less than three years.5 Countries can experience rapid deteriorations in risk ratings because of exogenous factors, such as global commodity price declines or natural disasters. Experience since 2016 and evaluative evidence suggest that the assigned probabilities have often been overoptimistic.

Figure 3.2. Public Sector Debt/GDP for Debt Sustainability Enhancement Program versus Non-Debt Sustainability Enhancement Program IDA-Eligible Countries, 2010–19

Source: Staff estimates from World Development Indicators data.

Note: DSEP = Debt Sustainability Enhancement Program; GDP = gross domestic product; IDA = International Development Association.

Exempting countries at low risk of debt distress from the DSEP is not without risk. Exempting countries at low risk of debt distress from the DSEP’s requirement to implement PPAs is not without risk. It may incentivize IDA-eligible countries to pursue sustainable financing practices, but the strength of this incentive is unproven. The SDFP guidelines state that a change in risk rating during the FY will not change a country’s PPA eligibility status for that FY, as in Rwanda, where the assessed risk of debt distress moved from low in FY20 to moderate in FY21. However, the guidelines also indicate that exceptions could be considered and cite as criteria (i) a marked deterioration in the country’s debt sustainability outlook, coupled with a sharp increase in debt burden indicators, or a reassessment of the debt as unsustainable; or (ii) a deterioration driven by endogenous factors, including insufficient debt transparency.

Debt Coverage

The SDFP expanded coverage of public debt beyond that in the NCBP. The NCBP applied only to external nonconcessional borrowing to reflect that, at the time of its introduction, nonconcessional external borrowing was perceived as the predominant risk to debt sustainability. The SDFP expands coverage to all external and domestic public sector borrowing. This reflects more accurately the debt accumulation over the past decade that has led to higher debt risks in IDA-eligible countries. For some countries, domestic public sector borrowing played a significant role in the rapid rise in debt stress. The focus on public external debt under the NCBP occasionally resulted in large “debt surprises” when contingent liabilities (such as SOE debt) were realized or when guarantees had to be honored.

Incentive Structure for Borrowers and Creditors

IDA Allocation Set-Asides

The SDFP relies on potential set-asides of IDA allocations to incentivize DSEP countries to implement agreed-on PPAs. Countries that fail to implement agreed-on PPAs have a portion of their IDA allocation set aside (10 percent for countries at moderate risk of debt distress and 20 percent for those at high risk or in debt distress). Originally, set-asides were designed for a three-year IDA cycle. Over the first two years of an IDA Replenishment, those set-asides would remain within the country’s multiyear IDA allocation. However, if the country had not implemented agreed-on PPAs by the start of the third year of an IDA cycle, the set-aside for the third year and accumulated set-asides would be released to be reallocated across other IDA-eligible countries through the Performance-Based Allocation formula.

With the shortening of the IDA19 cycle in the face of unanticipated COVID-19 needs, the system for set-asides has been adjusted. Now, the SDFP set-aside and discount mechanism is Replenishment neutral, running continuously across IDA cycles while maintaining the incentive structure that underpins the PPAs’ implementation. A Replenishment cycle–neutral set-aside implies that unsatisfactory implementation of PPAs in any particular FY would generate a set-aside, which can be recovered in the next year if the PPA is implemented satisfactorily, regardless of when in the IDA cycle the set-aside happens.

Although there is no direct and concrete experience yet with the use of set-asides for failure to implement PPAs, experience with the NCBP provides some insight into the credibility and efficacy of underlying incentives. The NCBP, like the SDFP, allowed for sanctions in response to a failure to adhere to the policy in the form of reductions in IDA allocations and hardening of IDA terms. Since 2015, there have been 17 cases of NCBP breach in six countries. As noted in the 2019 NCBP review (World Bank 2019b, 8), waivers for most breaches were granted ex post, which does not provide confidence in the strength of the incentive to adhere to the NCBP. IDA financing terms were hardened for three countries (Ethiopia, Maldives, and Mozambique). Hardening of terms usually involved converting some portion of the grant element of IDA financing into regular IDA credits. IDA allocation was reduced in only one country (Mozambique).

Although hardening of terms remains an option, SDFP incentives are expected to rely primarily on set-asides of future IDA allocations. Hardening of terms remains an option but is not expected to be used as the primary mechanism. This may reflect concern (articulated by World Bank management in the context of the 2006 NCBP policy paper) that a hardening of terms could make IDA financing relatively less attractive to countries with continued access to alternative sources of financing. Nevertheless, most of the cases of sanctions have involved a hardening of terms (World Bank 2019b, table 1). In light of the limited experience with using volume reductions, the credibility of a set-aside cannot be taken for granted amid a global economic crisis triggered by a pandemic, particularly given the importance that IDA has assigned to rapidly increasing commitments to affected countries. Therefore, there is a risk that weak PPAs could be adopted to try to reconcile the trade-off between PPA adherence and increased IDA commitment. At this point, there is little if any experience on which to base an assessment of PPA efficacy and the credibility of set-aside incentives.

The fact that IDA resources generally represent a declining share of IDA-eligible country finance might also make the credibility of a set-aside questionable. IDA has provided extraordinary support in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, but generally, IDA represents an increasingly small share of total net financial flows (debt and equity), particularly for market access countries. Among DSSI-eligible countries, IDA and International Bank for Reconstruction and Development lending represents only about 10 percent of net financial flows.

Program of Creditor Outreach

The PCO’s primary objective is “leveraging the World Bank’s potential as a convener to promote stronger collective action, greater debt transparency, and closer coordination among borrowers and creditors to mitigate debt-related risks.” This objective is similar to the NCBP’s, though with more ambitious aspirations for the range of creditors and countries with which to engage. There have been a number of workshops and meetings to date with other multilateral creditors and borrowing countries but modest engagement with non–Paris Club creditors, with the first major event planned for October 2021 (World Bank 2020c).

Review of the NCBP found that its PCO has had a positive but limited impact on creditors’ lending decisions. Multilateral and bilateral creditors, which formed the core of the global coalition for the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries Initiative and MDRI, were found to have engaged with the World Bank on sustainable lending practices. These creditors often have allocation mechanisms and lending procedures like IDA’s and were open to taking their lead from the World Bank and the IMF regarding assessment of debt sustainability. This coordination continues to be effective. The extent to which the new PCO represents significant additionality with respect to this group of creditors is therefore unclear.

Previous efforts at coordination with non–Paris Club and private creditors, including under the NCBP, produced little in concrete results. Engagement between IDA and non–Paris Club and private creditors was sporadic and generally limited to responding to requests for information through the Lending to LICs mailbox. The 2019 review of the NCBP did not offer findings on which to base improvements in collective action with non–Paris Club and private creditors.6 Given the significant role these two groups of creditors played in the rise in debt stress among IDA-eligible countries over the past decade (see figure 1.4), a successful PCO would need to lead to more effective collaboration with these groups of creditors. But it is not obvious that the World Bank on its own has sufficient leverage as a convener and enabler to promote substantive collective action and closer coordination among non–Paris Club and private sector creditors.

To date, there is little evidence of inroads made to strengthen collective action with non–Paris Club and private creditor groups. Given that these are the groups most implicated in the rise in debt distress over the past decade, the PCO’s success will hinge on performance in this area. Although the SDFP offers a general framework for outreach, and despite stakeholder events over FY21, the modalities and strategy for achieving PCO objectives with respect to non–Paris Club and private creditor groups have yet to be articulated. Experience to date, including with the NCBP, suggests that past practices are unlikely to be sufficient for success.

- The determination of countries under Non-Concessional Borrowing Policy eligibility reflects countries that would have been classified as International Development Association–only for fiscal year 2021. The determination of countries under Sustainable Development Finance Policy and Debt Sustainability Enhancement Program eligibility is based on the information provided in World Bank (2021c).

- A low-income country may eventually graduate from the Debt Sustainability Framework for Low-Income Countries and migrate to the Debt Sustainability Analysis for Market Access Countries when its per capita income level exceeds a certain threshold for a specified period or when it has the capacity to access international markets on a durable and substantial basis.

- Countries currently in nonaccrual status with the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development or the International Development Association are Eritrea, the Syrian Arab Republic, and Zimbabwe.

- Countries currently in this category are South Sudan and the Republic of Yemen.

- Twenty-four (of 75) International Development Association–eligible countries for which data were available over the 2012–19 period experienced an increase in their risk of debt distress. Of these, nine rose in debt distress risk from low to high (or from moderate to in debt distress), and the average time for the two-level increase was 2.7 years.

- The 2019 Non-Concessional Borrowing Policy review suggests expanding dissemination to creditors through a Lending to LICs (low-income countries) mailbox (World Bank 2019b), but there is no significant evidence that the mailbox has had an impact on creditor behavior.