The International Development Association's Sustainable Development Finance Policy

Chapter 2 | Origins of the Sustainable Development Finance Policy

Public debt burdens in IDA-eligible countries have risen substantially over the past decade. Between 2010 and 2019, general government gross debt as a share of GDP for IDA-eligible countries rose, on average, from 39 to 54 percent.1 Factors behind the debt built up in individual countries varied. They include (i) the availability of lending at the low interest rates prevailing after the global financial crisis coupled with new financial instruments and major changes in financial markets;2 (ii) encouragement of developing economy governments to increase spending to finance growth-enhancing investments; (iii) inefficient spending (including for many public investments), resulting in a lower rate of return than anticipated; and (iv) weak domestic revenue mobilization.

There were a variety of drivers of increased debt burdens. In an environment characterized by relatively inexpensive credit, many IDA-eligible countries expanded public investment, particularly in infrastructure, often with disappointing returns. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimates that approximately 40 percent of the potential gains from public investment in LICs was lost because of inefficiencies in the public investment process (IMF 2015). Many IDA-eligible countries spent heavily on inefficient energy subsidies or faced stagnant tax revenues (often caused by high tax exemptions and deductions, narrow tax bases, and inefficient revenue mobilization; Fatás et al. 2019). Spending to respond to natural disasters, particularly in small island states, was also a factor for the buildup in debt.

The shift to less-concessional financing reflected changes in creditor composition, which has increased borrowing costs significantly. Between 2010 and 2019, the share of nonconcessional borrowing in the total external debt of IDA-eligible countries increased from 43 to 60 percent. Although the share of nonconcessional debt among IDA-only borrowers has seen only a modest increase (from 44 to 48 percent of total external debt), the share of nonconcessional finance in IDA gap and blend countries has risen from 42 percent of total external debt to 66 percent.3 The increase in nonconcessional borrowing from bilateral and private creditors has exposed countries to shorter maturities and greater rollover risks and has crowded out other public spending. During the 2010–19 period, variable rate debt as a share of total external debt for IDA-eligible countries increased, on average, from 11 to 16 percent.

The rapid increase in borrowing over the past decade has drawn attention to weaknesses in debt transparency that hindered full awareness of and accountability for exposure to fiscal risk. Comprehensive debt reporting and debt transparency have featured strongly in recent discussions of debt sustainability. The World Bank has clear reporting standards for debt transparency in place for its borrowers (box 2.1). Specifically, World Bank borrowers are required to provide regular, detailed reports on long-term external debt owed by a public agency or by a private agency with a public guarantee. However, these standards have not led to full disclosure of external debt, particularly debt contracted by public entities that does not benefit from a sovereign guarantee. Information on terms and conditions of some debt instruments, such as bilateral debt restructuring by nontraditional creditors, is also limited. The World Bank’s debtor reporting requirements do not apply to domestic debt, which has been an important factor in rising debt stress for several IDA countries.

Box 2.1. The World Bank’s Debtor Reporting System

The World Bank’s Debtor Reporting System (DRS) is the most important single source of verifiable information on the external indebtedness of low- and middle-income countries. World Bank borrowers are required to provide regular, detailed reports on long-term external debt owed by a public agency or by a private agency with a public guarantee. Borrowers are also required to report in aggregate on long-term external debt owed by the private sector with no public guarantee. Currently, approximately 120 countries are reporting to the DRS, including all International Development Association–eligible countries.

Information the DRS required on new loan commitments is readily available from loan agreements. As such, complying with DRS reporting requirements should not place an undue burden on national debt offices. Most reports are now submitted electronically, and borrowers that use the debt management software provided by the Commonwealth Secretariat and the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development have access to an automated link that derives DRS reports from the national debt database. The quality of reporting to the DRS has improved significantly in recent years in parallel with enhanced debt management capacity for measurement and monitoring of external public debt in many low- and middle-income countries. Countries that have difficulty complying with the DRS requirements tend to be poorer International Development Association borrowers, typically fragile states or those in conflict.

The most significant gap in reporting to the DRS is the omission of borrowing by state-owned enterprises (SOEs), particularly SOE borrowing without a government guarantee. Although a few countries might underreport the extent of public debt liabilities deliberately, most SOE-related omissions reflect shortcomings in legal frameworks whereby the authority of the national debt office does not extend to collecting information on SOEs’ nonstate guaranteed debts, which are nevertheless implicit contingent liabilities of the government (this practice is not limited to developing countries). The World Bank’s Development Economics Vice Presidency, which manages the DRS, is actively pursuing avenues to close this information gap, including (i) collaborating closely with World Bank and International Monetary Fund country teams and staff on suspected underreporting, (ii) communicating directly with central banks and agencies responsible for compiling Balance of Payments and International Investment Position statistics that routinely collect information on borrowing by SOEs and private sector entities, (iii) reaching out to bilateral creditors for information on their lending activities, and (iv) maximizing the use of information from market sources and in creditors’ annual reports.

The DRS gives the World Bank both the tools and the leverage to improve debt transparency. Bank Procedure 14.10 clearly states, “As a condition of Board presentation of loans and financings, each Member Country must submit a complete report (or an acceptable plan of action for such reporting) on its foreign debt.” However, the World Bank has been reluctant to withhold lending for failure to meet debt reporting requirements, but it could do so. The Independent Evaluation Group was unable to find any instance of loans or financing being withheld because of incomplete reporting under the DRS. Data gaps that are linked directly to institutional lending imperatives have overridden strict enforcement of the World Bank’s policy. This has resulted in acceptance of aggregate reporting of public and publicly guaranteed debt by some large borrowers or deferral of the reporting requirement because of specific country circumstances.

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: International Development Association countries that receive only grants and with no outstanding debt obligations to the World Bank are not required to report to the DRS. These are typically small island economies—for example, Kiribati, the Marshall Islands, and Tuvalu.

Lessons from Review of the International Development Association’s Non-Concessional Borrowing Policy

The rise in debt vulnerabilities over the past decade underscored deficiencies in IDA’s NCBP. The NCBP came into effect in 2006 as part of IDA’s tool kit to support debt policies and long-term external debt sustainability after the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries Initiative and the Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative (MDRI). The policy was pursued through a two-pronged strategy designed to encourage appropriate borrowing behavior through disincentives to external nonconcessional borrowing by grant-eligible and post-MDRI countries and to enhance creditor coordination. By limiting nonconcessional borrowing, the NCBP also addressed institutional and IDA donor concerns with “free riding” by lenders offering nonconcessional terms (such as private bondholders and official lenders from countries that are not members of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) to grant-eligible countries because of cross-subsidization through IDA grants (World Bank 2006).

Earlier reviews of the NCBP noted shortcomings in achieving its objectives (World Bank 2015, 2019b). The NCBP lacked the capacity to stem the rise in IDA-eligible countries’ nonconcessional external borrowing over the past decade, partly because of its limited country and debt coverage. The NCBP covered only grant-eligible and nongap MDRI recipient countries, and it applied only to external nonconcessional borrowing, allowing for a subsequent rise in domestic debt (World Bank 2019b). The 2019 review concluded that the NCBP’s impact on creditor coordination had been “effective but limited in scope”—the NCBP was unable to meaningfully affect the lending decisions of non–Paris Club bilateral and private creditors. Regarding influencing creditors’ behavior, the NCBP review found that multilateral and bilateral creditors that formed the core of the global coalition for the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries Initiative and MDRI were already engaging with the World Bank on sustainable lending practices. These creditors were often found to have allocation mechanisms and lending procedures like IDA’s and were open to taking the lead from the World Bank and the IMF regarding assessment of debt sustainability. By contrast, engagement with non–Paris Club bilateral creditors and private creditors was sporadic, with most interactions limited to requests to IDA for information through IDA’s Lending to LICs mailbox.

World Bank Response to Emerging Debt Stress in International Development Association–Eligible Countries

In response to rising debt distress, the IMF and the World Bank implemented a joint strategy for addressing debt vulnerabilities in LICs. The Multipronged Approach to Addressing Emerging Debt Vulnerabilities came into effect in 2018 and comprised actions to (i) strengthen debt transparency by working with borrowing countries and creditors to compile and make better public sector debt data available, (ii) support capacity development in public debt management to mitigate debt vulnerabilities, (iii) provide suitable tools to analyze debt developments and risks, and (iv) adapt the IMF and World Bank surveillance and lending policies to better address debt risks and promote efficient resolution of debt crises (World Bank 2019c).

The multipronged approach encompasses many of the existing instruments and tools the World Bank uses to support IDA-eligible countries in creating fiscal space for growth-enhancing investments and to enhance debt management. These instruments include channels to (i) improve the efficiency, effectiveness, and equity of revenue collection; (ii) establish and strengthen systems for budget preparation and management (including public expenditure management, public sector accounting, PIM, and internal and external accountability); and (iii) build capacity to manage government assets and liabilities efficiently, including for macroeconomic policy and fiscal risk management purposes. The support takes varying forms, including through investment projects, advisory services and analytics, development policy operations (DPOs), and technical assistance.

IDA19 deputies and borrower representatives asked IDA to present options for adapting its allocation and financial policies to minimize risks of debt distress. These options were expected to ensure continuation of IDA’s focus on financial sustainability while supporting the achievement of country-specific development goals. An Options Paper was presented to IDA deputies, in which World Bank management proposed replacing IDA’s existing NCBP with the SDFP (World Bank 2019a).

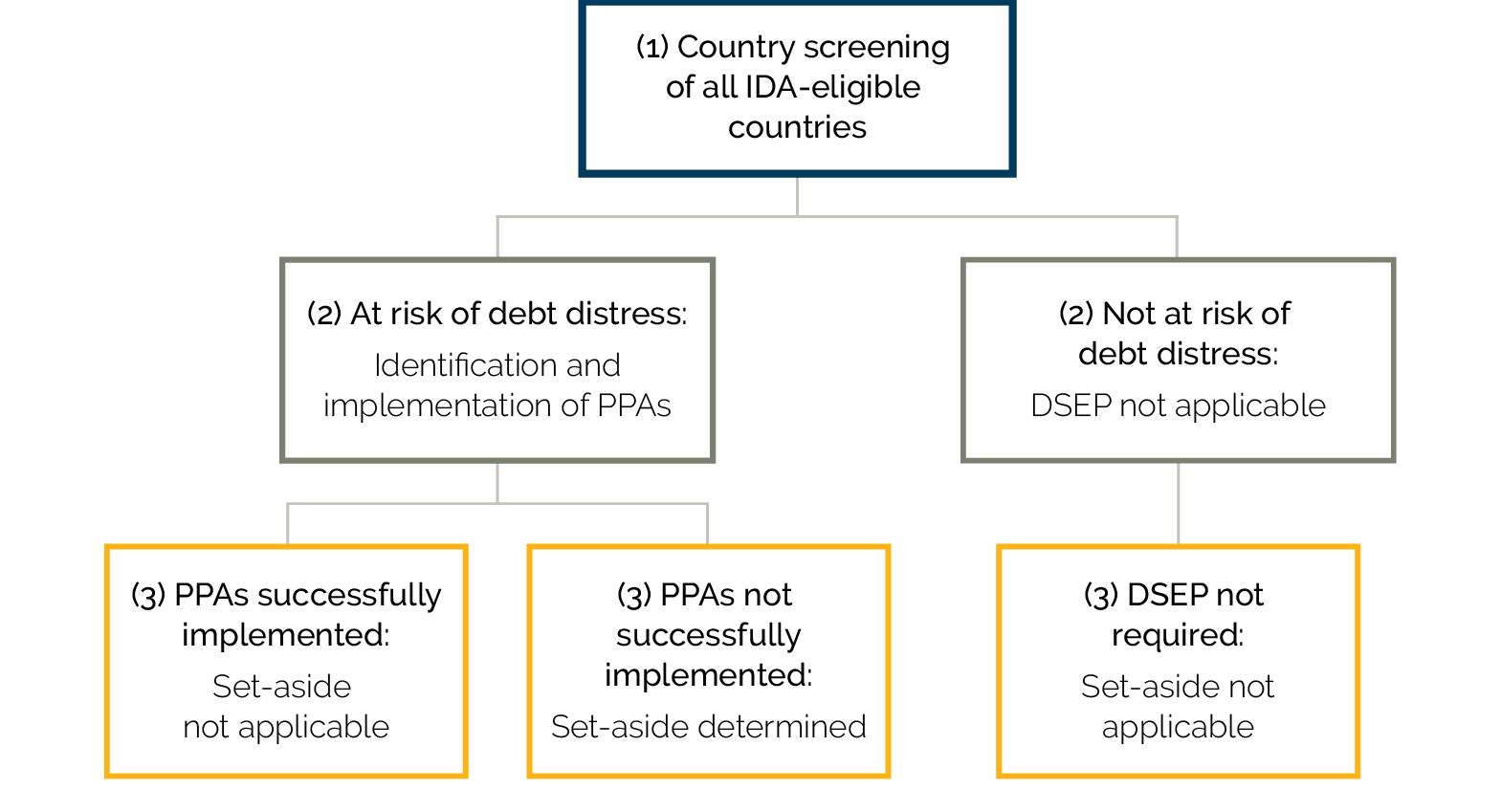

The SDFP is composed of the DSEP and the PCO. The DSEP seeks to create country-level incentives to enhance debt transparency and fiscal sustainability and to strengthen debt management. It does so by screening countries by levels of risk of debt distress and requiring countries at heightened levels of risk to undertake actions that would move the country toward more sustainable borrowing practices. Countries that do not undertake such actions successfully would be penalized through set-asides of their core IDA allocations. The key elements of the DSEP are as follows:

- Country screening: An initial screening of IDA-eligible countries to identify those at heightened risk of debt distress (using the World Bank–IMF Debt Sustainability Framework).4 Those at moderate risk of debt distress, high risk of debt distress, or in debt distress are required to implement PPAs.5

- PPAs: Countries subject to the DSEP define PPAs to address critical drivers to debt vulnerabilities. PPAs are implemented through lending instruments, technical assistance, and analytical work.

- Set-asides: Countries that fail to implement agreed-on PPAs have a share of their IDA allocation set aside (10 percent and 20 percent for countries at moderate and high risk of debt distress, respectively) and released only on satisfactory implementation of the agreed-on PPAs (figure 2.1).

Figure 2.1. Debt Sustainability Enhancement Program Implementation Framework

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: The DSEP includes some countries without risk ratings of debt stress (that is, countries with Debt Sustainability Analysis for Market Access Countries). DSEP = Debt Sustainability Enhancement Program; IDA = International Development Association; PPA = performance and policy action.

The PCO seeks to promote collective action at the creditor level to reduce debt-related risks to IDA-eligible countries. The program operates through promotion of greater information sharing, dialogue, and collective action among IDA-eligible country creditors, including traditional and nontraditional creditors (figure 2.2).

Figure 2.2. Program of Creditor Outreach Implementation Framework

Source: World Bank 2020b.

Note: SDFP = Sustainable Development Finance Policy.

The Group of Twenty (G-20) countries announced a Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI) when it became clear early in 2020 that the COVID-19 pandemic would have significant and negative implications for debt sustainability in many LICs. The DSSI offered a suspension of debt service repayments to G-20 bilateral creditors due from May 1 to December 31, 2020, for 73 countries that the United Nations classified as IDA-eligible or as “least-developed.” By late 2020, 43 countries had asked for support under DSSI, deferring just more than an estimated $5 billion in debt. The DSSI was subsequently extended to debt service due in 2021. The IMF also offered debt service relief to 29 of the poorest countries through the Catastrophe Containment and Relief Trust (IMF 2020c). The recently adopted G-20 Common Framework for Debt Treatments beyond the DSSI coordinates a sovereign debt solution that brings together Paris Club and other G-20 bilateral creditors and requires participating debtor countries to seek treatment at least as favorable from other bilateral and private creditors as that agreed to under the framework.

A secretariat in the Development Finance Vice Presidency manages the SDFP implementation and has compiled guidance for country teams for both the selection of PPAs and for drafting the PPA note. It also manages the PPA database and tracks their implementation. Technical staff in the Equitable Growth, Finance, and Institutions Global Practice’s debt unit provide guidance to country teams in developing PPAs, which an SDFP committee reviews. Final decisions on the PPAs and set-asides are taken by the managing director, on the recommendation of the regional vice presidents and the concurrence of the respective vice presidents of the Development Finance Vice Presidency; Operations Policy and Country Services; and Equitable Growth, Finance, and Institutions, with the advice of the SDFP Committee (see appendix B for discussion of SDFP governance arrangements). Together, these mechanisms seek to ensure that PPAs are based on sound diagnostics of the drivers of debt stress, reflect policy dialogue with and approval by country authorities, and support an ambitious but realistic pathway toward debt sustainability (World Bank 2020d).

Figure 2.3 sets out the framework through which the SDFP is expected to contribute to improvement of debt sustainability in IDA-eligible countries.

Figure 2.3. Sustainable Development Finance Policy and Its Role in Promoting Debt Sustainability

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: DSEP = Debt Sustainability Enhancement Program; G-20 = Group of Twenty; IDA = International Development Association; PCO = Program of Creditor Outreach; TA = technical assistance.

- Weighting by gross domestic product, the share of gross government debt rose from 32 to 49 percent over the period.

- This includes the rise of regional banks, a growing appetite for local currency bonds, the availability of concessional and nonconcessional lending from non–Paris Club creditors, and increased demand for emerging market and developing economy debt from the nonbank financial sector (Kose et al. 2021).

- International Development Association (IDA) gap countries are those above the operational cutoff for IDA but lacking the creditworthiness to borrow from the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development. IDA blend countries are countries eligible for IDA based on per capita income but also creditworthy for some International Bank for Reconstruction and Development borrowing.

- The Debt Sustainability Framework uses a set of indicative policy-dependent thresholds against which baseline scenario projections of external debt burden indicators over the next 20 years are compared to assess the risk of debt distress. Vulnerability to external and policy shocks are explored in alternative scenarios and standardized stress tests. The indicative threshold for each debt burden indicator is adjusted to reflect each country’s policy and institutional capacity as measured by three-year moving averages of the World Bank’s Country Policy and Institutional Assessment scores.

- Exceptions include countries with loans and credits in nonaccrual status and countries that are eligible for funding from IDA’s Remaining Engaged during Conflict Allocation.