State Your Business!

Chapter 2 | Effectiveness of Bank Group Support to SOE Reforms

Highlights

This chapter examines the performance of the World Bank Group’s energy and financial sector portfolio of support for state-owned enterprise (SOE) reform, analyzing factors associated with success.

The SOE reform portfolio in these sectors, on average, met the World Bank and International Finance Corporation corporate targets for project success.

The Bank Group overall engages far more with state-owned commercial banks than with state-owned development banks. The success rate for development bank SOE reform interventions exceeded that for commercial bank interventions.

SOE reforms in the transmission and distribution sectors were the most effective, followed by power generation; those dealing with extractive industries (petroleum, gas, and mining) were successful only half the time.

Several factors at the country and project levels are predictive of intervention success—some within the Bank Group’s control and some outside of it.

Control of corruption at the country level is strongly associated with intervention success. Other things being equal, SOE reform interventions in a country with high control of corruption are more than twice as likely to succeed than in a country with low control of corruption.

Five project-level factors not directly controlled by the Bank Group (though potentially influenced by it) are strongly associated with successful SOE reform interventions:

- Client commitment to the reforms and reform activities;

- Coordination among donors and other stakeholders;

- Client institutional capacity and coordination;

- Political economy and vested interests; and

- External shocks (natural or other) posing both obstacles and opportunities.

Four internal factors at the project level that are under the Bank Group’s direct control are strongly associated with successful SOE reform interventions:

- Project design, including the appropriate choice of instrument, adaptation to local conditions, and simplicity (versus complexity);

- Supervision, including having in-country expertise during project implementation (especially for investment projects);

- A strong results framework with active monitoring and evaluation; and

- Sequencing of interventions, including link to prior analytic work.

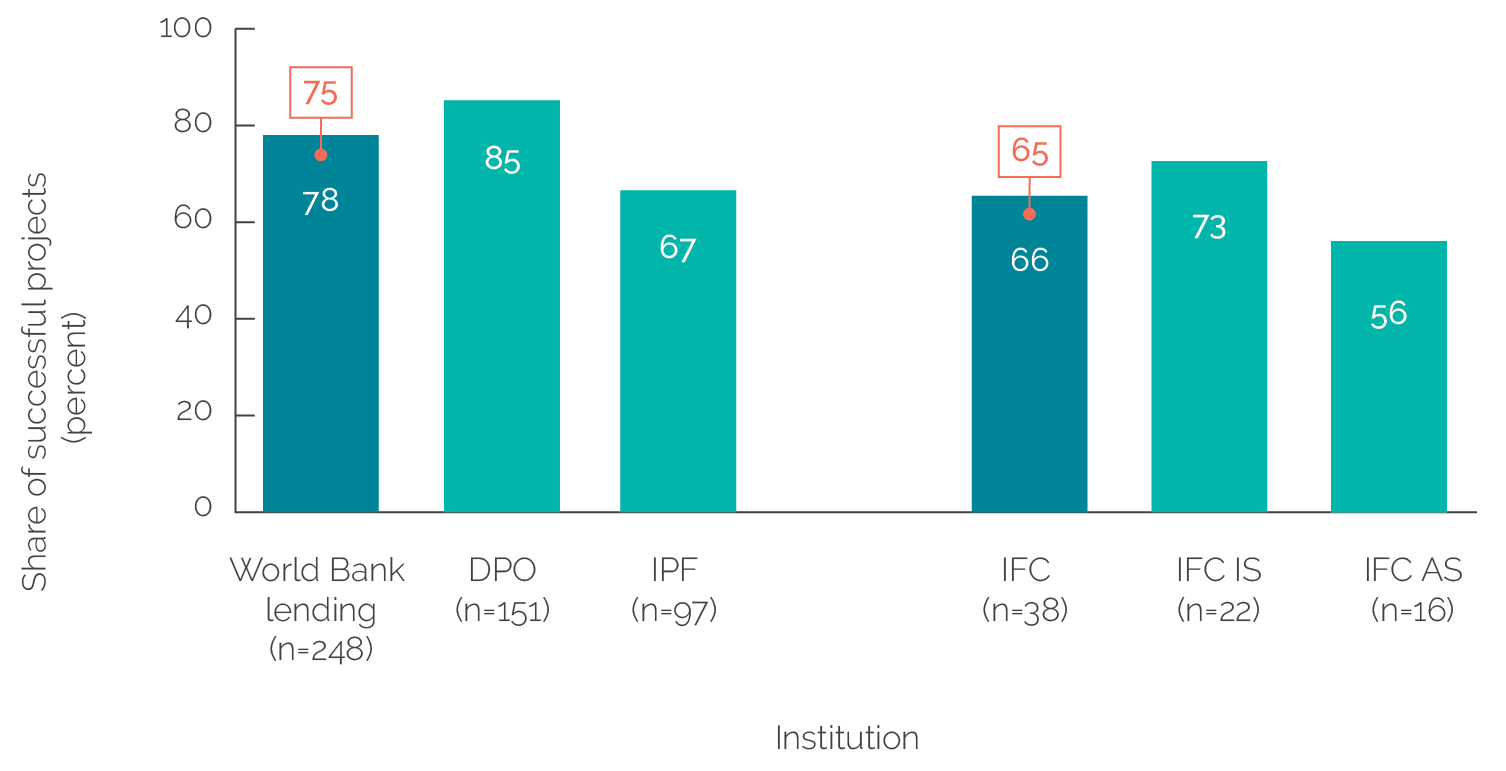

SOE Reform Performance in the Portfolio and Literature

On average, the overall SOE reform portfolio in the financial and energy sectors reviewed met the World Bank and IFC corporate targets for project success (figure 2.1). World Bank lending achieved an overall success rate of 78 percent against a target of 75 percent. Development policy lending (151 evaluated projects) achieved a success rate of 85 percent versus the investment project finance success rate of 67 percent (97 evaluated projects), but the two instruments focused on tackling different SOE reform challenges. Policy lending was more focused upstream, seeking to improve public finances; accountability, transparency, and oversight; or sector competition and productivity. Investment lending was more focused downstream, aiming to strengthen enterprise operational and financial performance as well as service delivery and quality. IFC achieved a success rate of 73 percent for investment services (22 evaluated projects) and 56 percent for advisory services against an overall target of 65 percent. Investment services were far more likely than advisory services to support improving service delivery and quality, and advisory services were far more likely to support strengthening financial and operational performance and improving transparency and oversight. Two evaluated MIGA guarantees both achieved their outcomes.

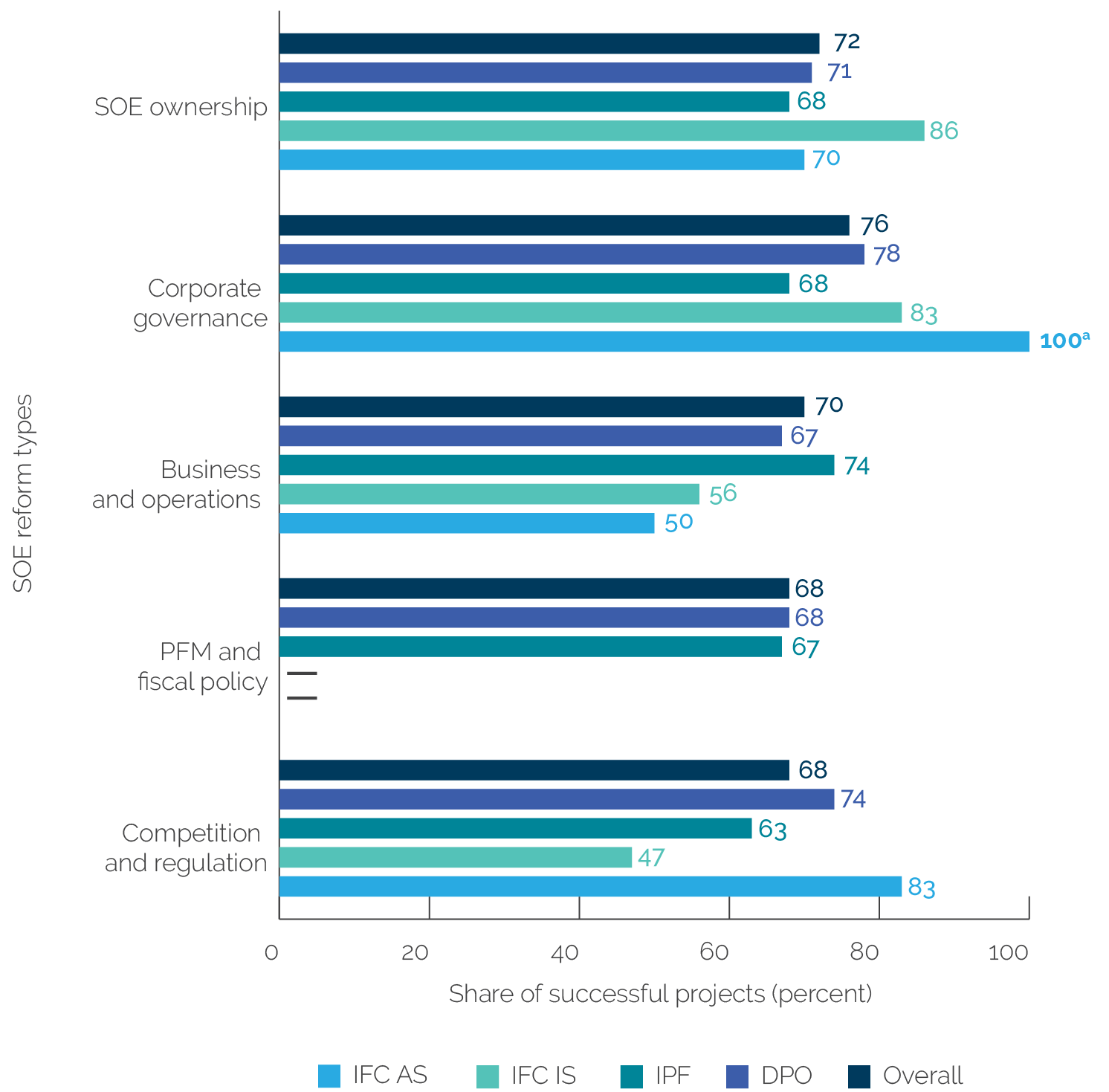

Across the five SOE reform types discussed in chapter 1, Bank Group projects supporting corporate governance, ownership reform, and business and operations showed statistically significantly higher success rates than did reforms in macrofiscal, and PFM and in competition and regulation (figure 2.2). World Bank DPOs were significantly more effective on average when pursuing competition and regulatory reforms than they were in the other four areas and significantly more successful at pursuing SOE ownership and corporate governance reforms than in pursuing business and operations and macrofiscal, and PFM reforms. World Bank investment operations were significantly more successful in pursuing business and operations reforms than they were in the other four areas but were also quite successful in pursuing privatization and corporate governance. They were relatively less successful in supporting reforms in competition and regulation and in macrofiscal and PFM.

Figure 2.1. Success Rate of State-Owned Enterprise Reform Projects Evaluated, FY08–18

Sources: Independent Evaluation Group portfolio review and analysis; World Bank Corporate Scorecard (updated to October 2017).

Note: The figure is based on 286 projects. The analysis excludes six World Bank lending projects for which outcome ratings were not available, rated, or applicable and three Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency guarantees, which achieved their intervention outcomes. The orange dots show FY17 corporate satisfactory outcomes targets. IFC updated its scorecard in November 2019 and eliminated its corporate success target of 65 percent. A project is now defined as “above the line,” or successful, if it is achieving or mostly achieving project outcomes. DPO = development policy operation; FY = fiscal year; IFC = International Finance Corporation; IFC AS = International Finance Corporation advisory services; IFC IS = International Finance Corporation investment services; IPF = investment project financing.

Figure 2.2. Success Rate of SOE Reform Interventions by Type and Instrument (Bank Group Evaluated by IEG)

Source: Independent Evaluation Group portfolio review analysis.

Note: n = 147 SOE ownership evaluated interventions (73 DPO, 47 IPF, 14 IFC IS, 10 IFC AS, and 3 Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency); 137 corporate governance evaluated interventions (88 DPO, 41 IPF, 6 IFC IS, and 2 IFC AS); 136 business and operations evaluated interventions (30 DPO, 89 IPF, 9 IFC IS, and 2 IFC AS); 22 fiscal policy evaluated interventions (19 DPO and 3 IPF); and 244 competition and regulation evaluated interventions (129 DPO, 94 IPF, 15 IFC IS, and 6 IFC AS). DPO = development policy operation; IEG = Independent Evaluation Group; IFC AS = International Finance Corporation advisory services; IFC IS = International Finance Corporation investment services; IPF = investment project financing; PFM = public financial management; SOE = state-owned enterprise.

a. n < 5 interventions.

IFC investment operations were significantly more successful at pursuing ownership reforms than they were in other areas but also had a high average success rate for the small number of corporate governance reforms evaluated. Advisory services had a higher average success rate in ownership, corporate governance, and competition and regulation, but with small numbers of evaluated projects for which statistical significance could not be compared. Although overall Bank Group privatization support was highly successful in both the energy and financial sectors, corporate governance reform was highly successful only in the financial sector (85 percent) and had a weaker record in the energy sector (62 percent).

The Bank Group’s success rate for development bank SOE reform interventions (77 percent) exceeded that for commercial bank SOE reform interventions (69 percent). However, the Bank Group overall engages far more with state-owned commercial banks than it does with state-owned development banks. For example, IFC successfully financed the turnaround and further privatization of Pakistan’s largest bank, Habib Bank Limited, through a $50 million loan and a $50 million equity investment. IFC supplemented this with advisory services (training) to strengthen staff and managerial capacity. Bank Group engagement with nonbank financial institutions is limited. World Bank investment projects supporting commercial state-owned bank reform fare poorly (61 percent success rate), but DPOs perform better (74 percent success rate). The reverse pattern holds for state-owned development banks: investment operations fare well (90 percent) and DPOs poorly (50 percent). For both categories of state-owned banks, support for business and operations was the most common, including support for risk management, product service improvement, and human resource management. Of 265 non-ASA financial sector SOFI interventions, 9 supported privatization of commercial banks, and 7 more supported privatization of other financial institutions. Eight ASA interventions of the 116 identified supported privatization.

In the power sector, SOE reforms were the most effective in the transmission and distribution sectors, followed by power generation; those dealing with extractive industries (petroleum, gas, and mining) were successful only half the time (box 2.1). IEG’s 2019 synthesis of findings on utility reform found that in the power sector, investment projects were more successful than DPOs at improving the overall financial performance of electric power utilities, but DPOs were more effective at influencing tariff adjustments. In power, IFC enjoyed substantial success in both investment services (88 percent) and advisory services (78 percent).

Box 2.1. Bank Group Engagement in Extractive Industries State-Owned Enterprise Reform

The oil, gas, and mining sector faces a unique set of environmental, social, and economic challenges and has a wide range of stakeholders (appendix E). State control is prevalent in the oil and gas sector, owning about 90 percent of reserves and 55 percent of production. In mining, state-owned enterprises have historically been less influential. The performance of national oil companies varies substantially according to state goals, geology, government interactions with the oil companies, and management strategy. Managerial and technical capacities are important to value creation.

Country case studies highlight interventions in the Arab Republic of Egypt, Kenya, Mozambique, Serbia, Ukraine, and Vietnam. Those in Egypt, Kenya, Ukraine, and Vietnam addressed improving the supply, prices, and reliability of natural gas or electricity supply. In Mozambique, reforms supported mining industry compliance with the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative.

Overall, the Independent Evaluation Group’s portfolio analysis identified 65 state-owned enterprise reform interventions through 34 projects. The majority (94 percent) are upstream World Bank lending interventions in oil and gas. Sub-Saharan Africa has more projects but less success (56 percent) than most other Regions. Success factors include client commitment, project design, and supervision. Negative factors include external shocks, weak monitoring and evaluation, insufficient public sector capacity, design issues (for example, complexity), and lack of client commitment.

Sources: NRGI 2019; Wolf 2009; Independent Evaluation Group deep dive on state-owned enterprise reform in extractive industries.

IEG’s in-depth reviews and literature review yield evidence of SOE reform success in three of the five reform types: privatization, corporate governance reform, and competition (unfortunately, this literature sheds little systematic light on the other areas of SOE reform). The literature consistently finds superior performance of private and privatized companies over public companies in both the energy and financial sectors and has especially negative findings about state-owned commercial banks. Multiple national and cross-national studies have shown the benefits of privatization (appendix G). A comprehensive literature review found that the studies focusing on before and after performance of privatized SOEs evidenced “significant improvements after companies are divested” (Megginson 2017, 1). It also found that China’s model (a socialist market economy based on a prominent role of public ownership and state-owned enterprises) evidenced “abysmal relative performance of state-controlled versus private firms in key industries—especially petroleum, banking, and technology” (50). On corporate governance, a small number of national studies of reforms have found that there were benefits to SOE performance but also that implementation of reforms is often incomplete. On competition, the literature shows that enhanced competition improves SOE performance in both the financial and power sectors on its own and as a complement to other reforms.

In the banking sector, research repeatedly finds that state-owned commercial banks perform poorly relative to private commercial banks (appendix G). There is “little evidence that government bank ownership provides substantial benefits (relative to other types of ownership) to the banking sector, the real economy, or users of banking services, especially in developing countries” (Cull, Pería, and Verrier 2018). Ho, Lin, and Tsai (2016) find that, for 39 countries, privatized banks outperform nonprivatized banks, that this benefit is larger in developing than in developed countries, and that good governance benefits privatization in developing countries. There is some evidence that well-managed state-owned development banks can direct credit to areas of policy priorities and benefit from a clear yet flexible mandate, adequate regulation and supervision, effective corporate governance and management, financial sustainability, and regular performance assessment (Abraham and Schmukler 2017). State-owned banks played a more positive role in countercyclical credit provision or, to be precise, were less procyclical in some countries than were private banks (Cull, Pería, and Verrier 2018). However, evidence is mostly negative regarding government ownership’s effects on bank competition, efficiency, and the stability of financial systems. There are mixed results on financial access. One study found that “women are more likely to be excluded from the financial sector where... state-owned banks have a bigger share in the banking system” (Morsy 2020).

Bank research has found that client country bank performance usually improved after privatization (Clarke, Cull, and Shirley 2005). The privatizations of Uganda Commercial Bank and the South African Stanbic Bank improved profitability and financial access (Rabiei and Rezaie 2013). A cross-country study in Southeast Asia and a panel of 22 developing countries found that bank privatization raises bank profitability and efficiency over time, even when the acquirer is a foreign bank (Boubakri et al. 2005; Williams and Nguyen 2005).

In the power sector, the World Bank’s research finds that “governance scores tend to be systematically higher for private utilities” (Foster and Rana 2020, 12). The efficiency of privatized utilities is “on par with the top half of performers among public utilities.” Only privatized utilities ever achieve full capital cost recovery. However, this research cautions that privatization of distribution utilities is rare and should be pursued only when enabling conditions are met, including adequate functioning of the utility and a strong authorizing environment (Foster and Rana 2020, 14).

Rigorous evidence of the effectiveness of corporate governance reforms comes only from national studies. For example, Heo (2018) finds a positive relationship between financial performance and board size and transparency and disclosure for 320 Korean SOEs. For Lithuanian SOEs, Jurkonis, Merkliopas, and Kyga (2016) find that management and board independence relate positively to returns on equity. Rudolph (2009), analyzing four well-performing SOFIs in Canada, Chile, Finland, and South Africa, finds that they share an efficiency and profitability objective that shareholders measure regularly, professional and qualified senior management, proper risk management systems, and independence from government in their financing.

Whatever the theoretical power of corporate governance reforms for SOEs, their realization is often incomplete. The 2019 World Bank power sector reform flagship report finds evidence that good governance practices are strongly associated with improvements in cost recovery and operational efficiency of distribution utilities, but it also finds “a significant governance gap between corporatized public utilities and privatized ones. Also, public utilities practice better governance when they coexist alongside private utilities” (World Bank 2019b). Areas in which public utilities lag include lack of autonomy in decision-making on matters of finance and human resources, considerable interference in the appointment and removal of board members, shortcomings in the rigor of accounting practices, and more lax human resource practices, with less ability to reward good performers and fire bad ones.

There is strong evidence that competition improves SOE performance in both the power and financial sectors. An econometric assessment of power sector data for 36 developing and transition countries over 18 years found that economic performance gains arose mainly from the introduction of competition (Zhang, Parker, and Kirkpatrick 2008). Privatization or regulatory reforms were less effective without a competitive market. In the financial sector, the negative effects of bank concentration on firms’ access to credit are stronger in countries with higher shares of state bank ownership (Beck, Demirgüç-Kunt, and Maksimovic 2004). The benefits of bank privatization are greater when they take place in more competitive environments (Clarke, Cull, and Shirley 2005).

Factors of Success and Failure at the Country and Project Levels

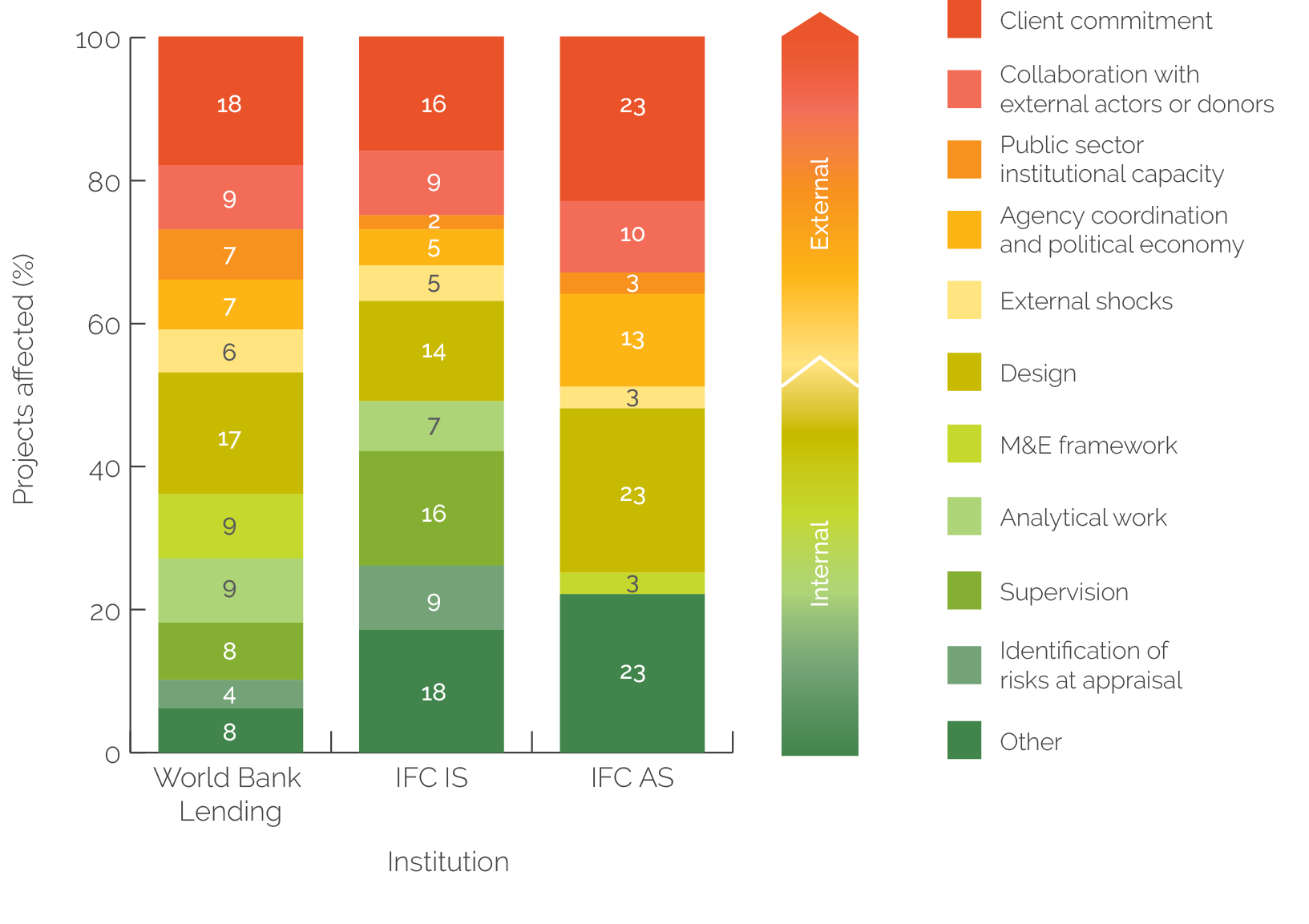

Several factors at the country and project levels are predictive of intervention success—some within the Bank Group’s control and some outside of it.1 IEG’s review of micro evaluative evidence from 294 projects and 671 interventions indicates several internal factors (those under the Bank Group’s control) and several external factors (those beyond its direct control) that are most commonly identified as explaining success or failure (figure 2.3). The leading internal factors include project design and supervision, the monitoring and evaluation (M&E) framework, and sequencing (including the availability of prior analytic work). The most common external factors are client commitment, collaboration with other donors and external actors, political economy, client capacity, agency coordination factors, and shocks. Client commitment and design quality are important across World Bank and IFC instruments, but supervision is a more common factor for IFC investment services, and political economy and agency coordination are more common factors for IFC advisory services. For IFC investments, identification of risks at appraisal is especially important.

Figure 2.3. Factors of Success and Failure for World Bank lending and IFC IS and AS

Source: Independent Evaluation Group portfolio review and analysis.

Note: Based on 857 factors identified for 294 evaluated projects. The projects can have multiple factors of success or failure. Excludes the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency. Percentages may not add up to 100 due to rounding. IFC AS = International Finance Corporation advisory services; IFC IS = International Finance Corporation investment services; M&E = monitoring and evaluation.

Design quality and client commitment are frequently identified as success factors across all five types of SOE reform support, although the frequency of other factors varies by area (figure 2.4). For example, risk at appraisal is more likely to be a factor in PFM and in fiscal (for the World Bank) and corporate governance reforms (for IFC and the World Bank), and supervision is relatively more important for privatization and ownership reform.

Figure 2.4. Frequency of Success and Failure Factors by SOE Reform Type

Source: Independent Evaluation Group portfolio review and analysis.

Note: Percentages may not add up to 100 due to rounding. M&E = monitoring and evaluation; PFM = public financial management; SOE = state-owned enterprise.

Business and operational reforms are relatively more sensitive to issues of agency coordination and political economy, and it is for these reforms that design and supervision issues are most likely to matter. Client commitment is a more frequent factor for both privatization and corporate governance reform than for other reform types.

At the country level, control of corruption is strongly associated with SOE reform success. Other things being equal, a country with high control of corruption is more than twice as likely to see SOE reform intervention success as one with low control of corruption. In conditions of weak public governance, it is more difficult to strengthen the governance, regulation, or performance of public enterprises.

The marginal effect of weak control of corruption is large, but in practice, several factors mitigate its negative influence on success. In the evaluated portfolio, the success rate for countries with low control of corruption is about 67 percent, but it is 76 percent for those with high control of corruption. Given the Bank Group’s commitment to engage in all client countries, it is not surprising that a significant minority of projects are in countries with characteristics predictive of a lower level of success. Overall, 26 percent of the identified portfolio was in countries with low control of corruption.

Corruption powerfully undermines performance. In Ukraine, for example, the Country Partnership Framework FY17–21 review and the case study found a widespread challenge of corruption and state capture impeding SOE reform progress. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development reported that by June 2018, more than 194 of the National Anti-Corruption Bureau’s 793 criminal proceedings dealt with about 50 SOEs and their officials. In Kenya, petty corruption among the field staff responsible for installing and reading meters reportedly frustrated efforts to stem power system losses, at least in part. The Vietnam case study found that cross-ownership among banks was a significant problem, opening the door to corruption and conflicts of interest. In Bangladesh, weak governance allowed huge banking scandals that wracked state-owned commercial banks (box 2.2).2

Box 2.2. The Sonali-Hallmark Scandal in Bangladesh

The Sonali-Hallmark scandal was one of several that plagued the state-owned commercial bank system after the World Bank–supported drive for strengthened corporate governance, privatization, and better oversight was abandoned in 2009. A single branch of Sonali Bank gave loans valued at about $454 million based on fraudulent documents. Fraudulent letters of credit to fictitious companies, combined with collusion or inaction by the Sonali Bank Board and the Bank of Bangladesh, enabled massive fraud. In 2014, Sonali Bank was reported to have a nonperforming loan ratio of 37 percent. Loans were assessed not according to their business potential, but with an eye toward “the influence or the connections of the person” asking for credit. Observers noted a strong incidence of default for loans approved by party-connected bank directors.

Sources: Allchin 2016; Economist 2014.

IEG analyzed successful projects in countries with weak control of corruption and found that they shared features that may mitigate adverse country conditions, thus improving their chance of success. These features include the internal factors of simple, selective, and flexible project design; prior analytic work;3 and strong supervision. Externally, they include strong client commitment and collaboration with external actors and donors. These factors combined explain the relatively high success rate (68 percent) of Bank Group projects in countries with low control of corruption. For example, the $150 million Guatemala financial sector adjustment loan (evaluated in FY08) largely succeeded in its sector reform objectives. Rooted in a prior Financial Sector Assessment Program, it was accompanied by technical analysis and support through active supervision. Continuous policy dialogue was key to maintaining government commitment through two administrations. IFC’s Zalkar Bank privatization project (592127) in the Kyrgyz Republic (approved in FY12) achieved its objective to support a bank privatization. IFC identified a buyer capable of implementing a restructuring plan to improve Zalkar Bank’s financial and operational performance. The project benefited from a flexible design that was well adapted to local circumstances as well as strong supervision by a well-composed team that included the local knowledge needed to navigate local regulatory requirements. Collaboration with external actors (including the International Monetary Fund) enhanced the government’s commitment to implement recommendations.

External Factors of Success

Five factors at the project level not directly controlled by the Bank Group (though potentially influenced by it) are strongly associated with the success of SOE reform interventions:

- Client commitment to the reforms and reform activities;

- Coordination among donors and other stakeholders;

- Client institutional capacity and coordination;

- Political economy (which can work for or against reforms, whereas vested interests often frustrate them); and

- External shocks, whether natural or human made, posing both obstacles and opportunities.

Client commitment underpinned success in multiple countries, including sustained periods of power sector reform motivated by strong government commitment to improving power supply and expanding or universalizing access to electricity. Underlying government commitment helped drive reforms in the Arab Republic of Egypt, Kenya, and Vietnam. In Vietnam, government commitment to rural electrification became the basis for sector reform. In Mozambique, there was strong ownership of the reform program under the sixth, seventh, and eighth PRSCs, and a proactive government stance led to progress in applying the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative. IFC benefited from client commitment with the 2008 Philippines Olongapo Power project, its first successful PPP transaction with a municipality. The City of Olongapo had demonstrated its support for a PPP by launching a previous tender (though unsuccessful), securing necessary central government approvals to implement a PPP, and committing $130,000 in fees to IFC to cover staff and travel expenses.

Results suffered where client commitment was inconsistent, as seen in the case studies of Bangladesh, Egypt, Kenya, Serbia, and Ukraine (appendix F). For example, in Ukraine, commitment to the implementation of corporate governance reforms in SOEs waned as the 2014 crisis receded. However, with the support of the World Bank and other international financial institutions, the government prepared a state-owned bank strategy and road map to improve state-owned bank governance, though implementation progress was slow and limited. In the energy sector, a supervisory board was established in 2015 to strengthen corporate governance for the SOE giant Naftogaz. Supervisory board members resigned by 2017, citing the government’s attempts to block reform of the company. The government later amended the board’s charter to reduce its power. Bangladesh’s lack of commitment to financial sector reform after 2009 undermined corporate governance reforms introduced with World Bank support in the first decade of the 2000s. In Serbia, a changing government agenda challenged the effectiveness of an IFC investment and advisory project. A new government in 2013 wanted to cancel privatization of a key state-owned bank, Komercijalna Banka ad Beograd. Long negotiations managed to restore the agenda with a new timetable, contending with political influence on many levels, and leading to the conclusion of a deal for its sale in early 2020.

Strong and durable coordination among donors contributes to effectiveness, allowing donors to work in complementary support of reform and leverage one another’s resources and influence. Ukraine saw strong donor coordination in 2014 in both sectors, but this had eroded in the gas sector by 2019. In Vietnam, donors engaged in a formal consultative group and business forum, and 14 development partners supported the 10-year PRSC series. Vietnam’s power sector has seen remarkable success, including achieving universal access to electricity and growth (and improved efficiency and cost recovery) to become the second-largest power system in Southeast Asia, with the expectation that it will soon become the largest. Donor support, led by the Bank Group, also involved major support from the Asian Development Bank and financing from the Japan International Cooperation Agency and the German Bank for Reconstruction. In Bangladesh and Kenya, the World Bank led energy sector donor coordination bodies over key periods. Ukraine and Serbia both sought alignment with the European Union (EU) Energy Package. Serbia’s EU accession drive led to de facto donor coordination. In Ukraine, deposit insurance was part of a broader package involving the International Monetary Fund and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development to reform the banking sector, wherein donors often conducted missions jointly. Conversely, in Kenya, other donors’ support for a large wind power project impeded least-cost planning and the utilities’ financial viability. The econometric analysis confirms that coordination with other donors and partners is a significant component predicting success.

High public sector institutional capacity aids development effectiveness in SOE reform projects. For example, IEG’s review of the Serbia Country Partnership Strategy for 2008–11 found that in a period of harmonization with the EU, implementation lagged legislation as capacity was built. “When projects are housed with strong institutions, it can take time to reach initial agreement, but prospects for successful implementation are high. Weak institutions are less likely to implement agreements even if there is a high level of formal ownership” (World Bank 2012b). Portfolio analysis of evaluated projects indicates that weak public sector institutional capacity often appeared as a negative factor and was the third most frequently identified external factor in project evaluations.

Weak coordination among clients’ agencies could hinder projects. Complex management with multiple government stakeholders yielded coordination challenges and overlaps in authority. In Kenya, IEG’s case study found that while the World Bank was working to build regulatory capacity in the Ministry of Petroleum, new legislation transferred regulatory authority to the Ministry of Energy. In Bangladesh, the Ministry of Finance inserted itself between state-owned commercial banks and the Bank of Bangladesh, weakening the financial sector regulator’s oversight authority. In Ukraine, multiple rival government committees played a role in energy sector reform, which complicated decision-making. For example, the transfer of the state-owned electric transmission company, UkrEnergo, from the Ministry of Energy and Coal Industries to the Ministry of Finance in late 2018 delayed key approvals and payments.

Political economy factors influencing projects included shifts in commitment arising from political considerations, opposition from vested interests, and a variety of political difficulties caused by electoral cycles and regime change. IEG’s SOFI deep dive (summarized in appendix E) found that countries such as Bangladesh, Egypt, and Indonesia have signaled their intent to privatize state-owned banks but later halted efforts because of internal political constraints. One route of political economy influence is public engagement, which can either broaden ownership of reforms or diffuse opposition. In Egypt, for example, when residents opposed construction of a power plant because of misinformation, rumors, and implementation missteps, the Bank Group reacted swiftly through an extensive public awareness campaign, offering jobs in construction projects to the community members and holding several conferences in the Giza North and Cairo areas. This allowed implementation to move forward. However, the overall level of the World Bank’s public outreach on SOE reform was found to be inconsistent, with considerable potential to raise engagement.

Vested interests can assert themselves in a wide variety of ways, ranging from subtle internal resistance in SOEs to overt legislative action. In Ukraine, for example, the opposition of affected oligarchs frustrated financial sector reforms and the resolution of nonperforming loans. One major impact occurred when they influenced the courts to reverse the nationalization of PrivatBank—billions of dollars of public resources had been used to nationalize and recapitalize the bank to protect the financial system’s stability. The court ruling would transfer these resources to the private owner, whose actions had necessitated the bailout. In both Bangladesh and Kenya, exceptions at times granted to vested interests disrupted least-cost planning and the competitive award of contracts to independent power producers. In Kenya, near-textbook arrangements for corporatization and corporate governance of the power utilities suggested independence of the boards and the regulator. However, in the 2017 election cycle, the government (mindful of politics) reportedly pressured Kenya Power to continue a high rate of rural connections (more than 1 million)—despite a fiscal shortfall that prevented a promised budgetary allocation—and pressured the regulator to not increase electricity tariffs. The result was a sectorwide solvency crisis with ripple effects from distribution to generation to transmission. IEG’s literature review further documents how electoral cycles can influence SOFI activity.4

External shocks, whether natural or human made, can create opportunity by compelling action, but they can also hinder reforms. In Ukraine, for example, the 2008 global financial crisis, the 2014 conflict with the Russian Federation, and the ensuing civil conflict created windows for reforming financial sector SOEs, although momentum was lost a few years later. In Egypt and Kenya, electricity supply crises drove greater engagement. Conversely, the 2011 Egyptian revolution disrupted the World Bank’s SOE reform engagement. In one specification, the econometrics found that external shocks are a negative predictor of success.

Internal Factors of Success

Factors under the Bank Group’s direct control are of strong interest because they are most subject to improvement through Bank Group attention and action. Four such internal factors directly controlled by the Bank Group are strongly associated with successful SOE reform interventions:

- Project design, including the appropriate choice of instrument, adaptation to local conditions, and simplicity;

- Supervision, including having in-country expertise during project implementation (especially for investment projects);

- A strong results framework with active M&E; and

- Sequencing and complementarity of interventions, including the link of activities to prior analytic work and internal collaboration.

Choice of instrument was cited in 23 cases as a factor of success or failure. In most cases, it was a positive influence because the instruments chosen responded to country needs, were strategic, and combined financing and technical assistance. IEG’s recent utility reform synthesis report finds that the relatively long implementation periods of investment projects allow more time for hands-on operational support and corrective measures in the process (World Bank 2020b). Conversely, the synthesis found that DPOs, with their financing contingent on policy reform, were more effective than investment projects at influencing tariff adjustments (71 percent versus 55 percent success). Programmatic DPOs achieved better outcomes in utility financial recovery than one-off DPOs, which were found to suffer from complexity, overdesign, and an insufficient time frame for implementation. The econometric analysis did not indicate that any one instrument was systematically more successful, but one specification did confirm that the correct choice of instrument was a predictor of success.

Flexibility and adaptation of design to capacity were frequently identified as factors associated with successful development outcomes in SOE reform projects. The Bank Group’s country-driven model is responsive to crises, adapts to differences in client capacity and priorities, and allows the Bank Group to leverage service delivery goals to reform SOEs. Crises pose both a danger and an opportunity regarding SOE reform. Shocks are negatively associated with project success, yet they often provide an opening for reform progress. In banking, over the evaluation period, the World Bank responded twice to crises in Ukraine: after the global financial crisis of 2008 and again after the Russian-Ukrainian conflict beginning in 2014. In between, client demand for reform was weak, but each crisis brought new commitment and some progress. In energy, case studies showed high Bank Group responsiveness in Bangladesh, Kenya, and Ukraine when they confronted serious power shortages, and in each case, the response included measures advancing SOE reform. In Ukraine, the World Bank provided timely support to the gas sector to address supply uncertainty, diversify sources, and build storage reserves. In Mozambique, when discovery of undisclosed SOE liabilities sparked a fiscal crisis in 2016, the World Bank responded with a program to strengthen public investment and fiscal management, addressing SOE debt and fiscal risks.

Adaptability has meant that in several cases where client sectoral capacity or commitment was initially low, the Bank Group has shown an ability to engage over the long term to enhance it. In the power sectors in Bangladesh and Vietnam and in China’s financial sector, capacity and shared understandings were built over time (box 2.3). Long-term engagement and mobilization of multiple complementary and sequential instruments have helped build capacity and Bank Group credibility. In some cases, the Bank Group leverages its efforts through both internal and external coordination.

Flexibility in adapting to lower client capacity can yield long-term results. In Mozambique, for example, the World Bank’s support for power sector reform originally aimed at unbundling the state power utility, Electricidade de Moçambique, with a separate transmission company and a newly created private market for distribution and generation. Progress was slow, and when new research signaled that unbundling was not the best course for low-capacity countries with small power sectors, the World Bank dropped unbundling and shifted its focus to increasing the role and effectiveness of the nascent national electricity regulator, Conselho Nacional de Electricidade, particularly in monitoring Electricidade de Moçambique.

The country economic model allows the Bank Group to adapt to some markedly different client priorities. In Vietnam, for example, the government has maintained ownership and control of thousands of SOEs, including the four largest banks, which make up almost half of total sector assets. Despite the political infeasibility of privatizing large state banks, the Bank Group has remained engaged with a large SOE reform program across the financial and energy sectors. With mixed effect, the World Bank has been able to engage (including through major analytic work) on work to separate regulation from ownership, strengthen the legal and institutional foundations of financial markets, and enhance regulation and stability. In energy, the World Bank worked with the government on unbundling in the power sector gradually as part of its efforts to improve sector performance and achieve universal electricity access. However, important differences between the World Bank and the government have remained on the pace of reforms and on pricing mechanisms.

In contrast to Vietnam, Serbia was aggressively pursuing a more orthodox set of reforms and EU accession, and the Bank Group mobilized to support its agenda. For example, IFC invested in two state-owned banks (Čačanska Banka and Komercijalna Banka ad Beograd). IFC aimed to strengthen Čačanska Banka’s capital base through a capital increase, improve its competitive position, enable it to bear likely stresses, and support its lending to the small and medium enterprise segment alongside the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, all to facilitate privatization. IEG’s case study found that IFC had contributed as a shareholder to improving the corporate governance of the two state-owned banks. In 2015, a majority share of Čačanska Banka was sold to a Turkish banking group.

One important entry point for the Bank Group on SOE reform is client desire to improve the quantity, quality, and consistency of service delivery. This is an explicit objective of 22 percent of SOE reform interventions that IEG reviewed (the second most common). However, engaging adaptably often achieves further SOE reform. With multiple power utilities, the Bank Group’s support for improved generation eased discussions of reforms to regulation, institutions, and operations reforms and private participation. For example, Vietnam prioritized rapid expansion of citizen access to electricity, so the World Bank’s support facilitated trust and broader conversations about utility reform. In the Bangladesh, Kenya, and Ukraine case studies, IEG found that severe deficiencies in power availability and reliability, along with ambitious access goals, increased willingness to partner with the Bank Group.

If adaptability is often a benefit, complex project designs undermine effectiveness, potentially overwhelming both client capacity and World Bank supervisory capacity. This problem appeared only in World Bank projects, which tend to have multiple components. In Kenya, for example, an effort to address the needs of an emerging extractive sector in energy comprehensively resulted in a highly complex project. The $50 million 2014 Kenya Petroleum Technical Assistance Project originally included 11 project components or subcomponents and three project implementation units, which had to engage with 21 counterpart executive agencies. At midterm, when it was only 19 percent disbursed, the project had to be restructured to simplify it and reduce the implementation agencies to one project implementation unit. Another example is the $250 million 2004 Enterprise Reform and Bank Modernization Project (P081969) in Bangladesh. This project was faulted in IEG’s Implementation Completion and Results Report Review for combining too many elements into a single project. Early attention focused on privatization of manufacturing industries (especially jute mills), with a loss of focus on state-owned commercial bank privatization, which the project also supported. A separate operation might have handled addressing state-owned bank privatization better, and by the project’s end, the window for reform had closed. In Ukraine, IEG found that a World Bank investment loan became too complex when it added substantial energy sector policy reform objectives. “Combining an ambitious sector reform program with significant investment activities in a fragile political economy carries high risks” (World Bank 2017e). In the Democratic Republic of Congo, a component of the $120 million Private Sector Development and Competitiveness Project (2003) on SOE reform was found to be too ambitious given the limited resources allocated, the weak client capacity, and the politically fragile environment.

Supervision is important to success, and having country and regional office experts on site helps. In the power sector in Bangladesh and Kenya and in Ukraine’s financial sector, on-site experts forged trust and partnership over longer tenures, reducing transaction costs and strengthening implementation and oversight. For IFC, evaluation showed that its success in supporting the initial public offering (privatization) of the geothermal energy company Energy Development Corporation in 2007 was enabled by a project team that included experienced local business developers with strong client relationship skills, and officers with power sector, corporate governance, and SOE knowledge and strong processing capabilities. However, experts not located on site sometimes faced problems, such as in supporting the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative in Ukraine. Positive aspects of team composition include strong local presence, necessary skills (or ready access to technical guidance), and continuity in project teams and supervision. Negative aspects of team composition include a high turnover of task team leaders, lack of adequate expertise in project teams, and delayed establishment of the project implementation unit. For example, the quality of supervision for the Mali Energy Support Project suffered from high turnover of task teams and the fact that most task team leaders were located in Washington, DC, instead of in the field (World Bank 2019b). The econometric analysis supports the predictive power of team composition (a combination of expertise, experience, and stability) as a predictor of success.

Projects in which M&E frameworks contributed to success had a clear statement of objectives and indicators that captured the achievement of the project’s development objectives. Such projects had well-specified actions, clear and monitorable outcome indicators, baseline and target values, and sources of information for tracking progress. For example, after restructuring, the modified indicators for the Zambia Increased Access to Electricity Services Project were found to be appropriately linked to the objectives and properly designed to monitor progress toward the project objectives. Furthermore, the M&E framework was useful to monitor progress and aided project refinement over the course of implementation (World Bank 2016c).

Poor M&E design (including results frameworks) undermined effectiveness. The portfolio review yields many examples of where effectiveness was constrained by projects failing to do the following: incorporate relevant quantitative indicators into the Project Appraisal Document for tracking the progress of projects, have consistent indicators over the life of the project and across similar projects, generate baseline data, establish a clear relationship between project activities and outcome indicators, report only outcomes attributable to the project, or effectively monitor or recalibrate indicators to reflect project changes. For example, the 2006 China Economic Reform Implementation Project lacked well-defined and measurable outcome indicators that could be monitored to facilitate project implementation. It failed to establish targets for its outcome indicators and monitor outcomes at the subproject level. Thus, the lack of relevant monitoring information was found to have impeded a midcourse correction during supervision. For the Ghana 2006 Economic Management Capacity Building Project ($50 million), the lack of a clear relationship between project activities and the outcome indicators made it difficult to see if the project was making adequate progress. In IFC’s 2011 project investing $307 million in VietinBank for small and medium enterprise banking and risk management, evaluation found that the M&E framework did not incorporate relevant indicators to track project results and performance against project objectives for the risk management component. The econometric analysis confirmed the significance of a good M&E framework as a predictor of intervention success (appendix D).

Sequential and complementary interventions aid success. Sequential engagements involving financing and technical and analytic support built institutional and physical capacity, and the trust of underlying relationships carried reform momentum through difficult periods.5 The econometric analysis confirmed that sequencing can be a significant predictor of intervention success. The case studies exemplify the benefits of sequenced and complementary engagements (box 2.3). In Kenya, for example, sequential engagements in the power sector supported broad reform, including upstream support of sectoral policy and planning; construction and rehabilitation of generation, transmission, and distribution infrastructure; capacity-building assistance to utilities, including improvement of their corporate governance; and strengthening of financing and the ability of state-owned utilities to attract long-term private capital to refinance short-term debt (see Kenya case study, appendix F).

Box 2.3. Sequencing and Complementarity to Build Credibility and Capacity

The World Bank Group strategies and programs in Bangladesh’s power sector were aligned with successive government five-year plans. From at least 2004, the Bank Group engaged in unbundling and building technical capacity through financing and technical assistance. This covered regulation, generation, transmission, and distribution. The World Bank also supported the Power Cell, which channeled technical, planning, and coordination support to government while facilitating the role of private power producers. The Power Cell is an acknowledged success, and the client owns it fully. The regulator, Bangladesh Energy Regulatory Commission, has benefited from Bank Group support since its creation. The World Bank, the International Finance Corporation (IFC), and the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency were all involved in a Cascade-type approach in supporting independent power providers. Over time, sector performance improved through reduced losses, reduced arrears, and an elimination of the energy gap. The Bank Group became a trusted partner in energy state-owned enterprise (SOE) reform through its expertise in the field, access to global expertise, long-standing relationships with key government agencies, coordination of donors, and consistent policy view.

In Vietnam’s power sector, the Bank Group engaged comprehensively in all aspects of the power sector (rural electrification, generation, transmission, distribution, load dispatch, renewables, development of wholesale and retail power markets, regulatory aspects, and SOE reform). The credibility and trust generated enabled the Bank Group to support the government in sequencing sectorwide reform. The Bank Group tapped a wide range of instruments to support SOE reform in both the energy and financial sectors, including seven Poverty Reduction Support Credits, three Economic Management and Competitiveness Credits, three power sector development policy operations, an energy sector loan, and four financial sector lending projects, along with significant analytical work. IFC engagement included four advisory services and one investment project in the financial sector. The Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency provided a guarantee for a hydropower project.

China’s financial sector saw complementary support by IFC (piloting state bank privatizations downstream) and the World Bank (knowledge generation, including flagship policy reports; joint studies; policy dialogue; and technical assistance). When the government chose to partner with IFC, IFC created models meant to have demonstration effects. IFC investments in the first decade of the 2000s supported the privatization or restructuring of three SOEs, and a focus on frontier regions contributed to increasing foreign direct investment flows. IFC worked to attract private investment to diversify state-owned financial institution ownership, also providing advisory services on insolvency and corporate governance. IFC investments and involvement in investee boards supported good corporate governance practices.

Source: Independent Evaluation Group case studies (see appendix F).

Analytic work before financing interventions figures prominently in sequencing and is the second most common factor of success or failure that project evaluations identified. The Bank Group has a plethora of analytic products producing findings relevant to SOE reform (box 2.4). Beyond informing operations, the Bangladesh and Ukraine case studies reveal that even where reforms stalled and the World Bank disengaged financially for a period, an ongoing program of analytic work in each case kept the World Bank current and offered a basis for reforms once conditions allowed. In most of the case studies, the Bank Group’s ability to share relevant knowledge arising from analytic work was a key source of comparative advantage among donors.

In Serbia, a decade of sequential and complementary support built a strong partnership on SOE reform. The Bank Group supported the Serbian government in reforming commercial SOEs for more than a decade and was one of the government’s few trusted partners. World Bank projects supported SOE restructuring, privatization, and improved corporate governance. IFC advisory services supported corporate governance reform. IFC joined the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development to provide long-term financing to two of IFC’s state-owned bank clients to prepare them for privatization. In 2015, one of the banks was sold, and the other, Komercijalna Banka ad Beograd, continued to be reformed and is expected to be sold to a private owner in late 2020. Other World Bank interventions aimed to improve fiscal discipline and management, reduce direct and indirect SOE subsidies, implement an electricity tariff adjustment, and support public expenditure reform. The World Bank also supported assistance to workers scheduled to be laid off in SOE restructuring and privatization and supported reforms in M&E, auditing, worker safeguards, and environmental standards compliance. Similar cases were found in the power sectors in Bangladesh, Ukraine, and Vietnam and in China’s financial sector.

IFC has also had sequential SOE reform engagements with key clients with notable effects. In 2005, IFC assisted the Bank of Beijing to strengthen its capital base, introduce international standards and practices, become a competitive regional player in the market, improve corporate governance and transparency, and establish an environmental and management system. The project benefited from an effective integration between investment and advisory services. IEG’s evaluation found that IFC placed a high regional priority on the bank and had a clear engagement plan, which it updated regularly. In 2007, IFC invested in a risk-sharing facility for the China Utility-Based Energy Efficiency Finance Program, building on the Bank of Beijing’s participation in IFC’s sustainable finance training. The relationship team actively coordinated introducing the program to the World Bank. An advisory team provided tailored services to the Bank of Beijing headquarters and branches in market development, product design, technical assessment, and relationship brokering with energy-efficiency vendors. In FY10, four training courses and three market promotions were conducted, which helped the Bank of Beijing establish its capacity in energy-efficiency finance, particularly for small and medium enterprises.

Box 2.4. State-Owned Enterprise Reform in World Bank Group Analytic Work

The Independent Evaluation Group (IEG) found substantial Bank Group analytic work identifying state-owned enterprise (SOE) reform priorities.

Systematic Country Diagnostics (SCDs). In a sample of 46 countries, IEG identified 39 SCDs, and 92 percent identified SOEs as a reform priority. Ninety percent of the SCDs focused on energy sector SOEs, and 26 percent focused on financial sector SOEs. These clearly informed country strategies: for the same sample of countries, 83 percent of Country Partnership Frameworks foresaw Bank Group work to support SOE reforms, mostly in sector-level regulatory framework reform and enterprise-level business and operational reform. SOE reform in more than one area is common.

Country Private Sector Diagnostics (CPSDs). All 10 International Finance Corporation–World Bank Country Private Sector Diagnostics (CPSDs) that IEG reviewed addressed SOE reforms. This relatively new, joint International Finance Corporation–World Bank CPSD tool aims to inform the SCD (and thus the Country Partnership Framework) and operations by assessing constraints to and opportunities for private sector–led growth. The CPSDs identified SOE issues ranging from reducing crowding out within the financial sector to reforming the independent power producer regime and sector planning in the energy sector. Ownership reforms were most frequent among the recommendations, but reforms in regulation, corporate governance, and competition were also common. Two recent CPSDs (Morocco and Rwanda) adopted the Markets and Competition Policy Assessment Tool’s competitive neutrality framework. The Morocco CPSD employs a full competitive neutrality gap analysis focused on SOE advantages, and the Rwanda CPSD makes competitive neutrality and strengthening of competition policy a key focal point.

Financial Sector Assessment Programs. Most Financial Sector Assessment Program reports, conducted jointly by the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, discuss and make recommendations about the reform of state-owned financial institutions. The same sample of countries for SCDs yielded 29 Financial Sector Assessment Programs, three-quarters of which substantially discussed these issues and reforms, most focusing on state-owned commercial banks. Upstream, the greatest focus was on sector regulatory frameworks, governance, and ownership. Downstream, the focus was on firm ownership.

Markets and Competition Policy Assessment Tool. This tool was introduced in 2016. By late 2019, IEG found only seven countries and one subregion with comprehensive Bank Group competition analyses. This analytic work systematically addresses both industrial structure and competitive neutrality issues pertaining to SOEs.

SOE Corporate Governance Assessments. IEG reviewed nine SOE Corporate Governance Assessments that followed the 2014 SOE Corporate Governance Tool with some variations. For example, only five of the nine addressed the first Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Corporate Governance of SOE Guidelines principle: the rationale for state ownership.

Integrated SOE Framework. IEG reviewed two works under the Integrated SOE Framework label: one for Niger and one for Sri Lanka. Substantial variations between the two suggest this product is still in development.

Source: Independent Evaluation Group reviews of analytic work for this evaluation.

Note: Late in the evaluation period, the World Bank introduced a new product, the Infrastructure Sector Assessment Program (InfraSAP), which aims to identify a mix of policy reforms and advisory and investment activities that would maximize commercial and private finance for infrastructure. However, only one relevant country study and one regional study were completed during the evaluation period.

Collaboration among Bank Group institutions, although relatively rare, can provide complementary support that aids SOE reform success. Among the diagnostic products described in box 2.4, the CPSD, which consistently treats SOE reform, is a strategic tool that IFC and the World Bank produce jointly. CPSDs provide a shared perspective on challenges and opportunities for private sector development (including concerning SOEs) as an input to Systematic Country Diagnostics and Country Partnership Frameworks. The MCPAT is also a shared World Bank and IFC platform of analysis for regulation and competition.

IEG found in several case studies an operationally collaborative approach consistent with Cascade, under which the World Bank, IFC, and MIGA work to their comparative advantages. Institutional collaboration to mobilize private financing is a key expectation raised in the MFD and Cascade approaches.6 The MFD and Cascade reinforce the existing World Bank Group Strategy calling for a “One World Bank Group” approach.7 Yet project evaluations identify collaboration as a factor that facilitated or constrained success in only 13 of 294 SOE reform projects.

Experiences in several countries show the operational promise of MFD and its embedded Cascade approach in power generation where Bank Group institutions work together to create conditions that attract private investment. For example, in Kenya, the Bank Group helped attract private investment in independent power providers through a risk mitigation package supported by International Development Association partial risk guarantees, MIGA guarantees, and IFC investment loans. This combination, together with IFC’s leadership in establishing a consortium of other financiers, raised private investors’ comfort level. The initiative stimulated the construction of 302 megawatts of installed power generation capacity, equivalent to about one-quarter of total national power consumption at the time. In Bangladesh, IFC’s joint engagement with MIGA and the Japan International Cooperation Agency enabled a PPP for the Sirajganj 4 generator project. This facilitated construction of one of the country’s largest and most efficient gas turbine combined cycle power stations to address chronic energy shortages and supply instability.

As observed in a recent IEG evaluation of joint projects, coordination requires an informed perspective on both benefits and costs (World Bank 2017f). For example, joint projects have been especially helpful in high-risk contexts. They have worked best where the Bank Group had a clear comparative advantage and where the roles, division of labor, and responsibilities among the different Bank Group institutions and respective project teams were clear. Realistically, the costs involved for internal coordination can require additional resources for administration, preparation, and implementation, regardless of commitment amounts.

At a corporate level, there is no clear road map for collaboration to support SOE reform. The implications of MFD and the Cascade and of sector strategies for how Bank Group institutions can work together to support SOE reform have not been spelled out. The implications of IFC’s new emphasis on upstream engagement to create, deepen, and expand markets bring new opportunities and challenges to coordination with the World Bank and MIGA.

- In this chapter, the Independent Evaluation Group triangulates from multiple evidence sources on World Bank Group effectiveness and factors influencing it. These include the portfolio review, microevaluations, country case studies, deep dives, literature reviews, and econometric analysis. The portfolio analysis draws on 294 evaluated projects with 671 intervention-level ratings. Because World Bank advisory services and analytics has no validated results framework, it does not represent a relevant evidence source. The Independent Evaluation Group undertook a rigorous econometric analysis to assess success factors to identify plausible explanatory variables associated with the achievement of state-owned enterprise (SOE) reform intervention outcomes, introducing country-level control variables. The analysis was based on a logistic regression model that sought to identify potential predictors of SOE intervention success. It included individual factors coded in the portfolio review and analysis, composite factors identified through principal component analysis, and country-level variables. The appendixes summarize findings from the portfolio analysis and the country case studies, econometric analysis, and country diagnostics and strategy reviews; however, they are not individually cited for each finding in the chapter.

- Imam, Jamasb, and Llorca (2019) found that in Sub-Saharan Africa, corruption reduces electricity sector technical efficiency and constrains efforts to increase access to electricity and national income. Chen et al. (2016) found that corruption is associated with underperformance of state banks.

- Analytical work was an important factor that influenced the positive outcome of 59 evaluated operations. Analysis showed that the Bank Group used analytical work to support project design, implementation, and government and client capacity building, as well as to ensure continuity in its engagement. For example, in Turkey, the Second Competitiveness and Employment development policy loan (P096840, FY08), which achieved its objective of privatizing an SOE and selling the state-owned assets, benefited from a large number of analytical works that fed a lasting, stable policy dialogue in the areas supported by the reform.

- Dinc (2005) provides cross-country evidence that government-owned banks increase their lending in election years relative to private banks; the effect is about 11 percent of a government-owned banks total loan portfolio. Claessens, Feijen, and Laeven (2008) show that Brazilian firms contributing to winning campaigns increase their bank financing relative to a control group after each election, with an economic cost of at least 0.2 percent of gross domestic product. Cole (2009) shows that Indian government–owned banks increase agricultural credit by 5 to 10 percentage points in an election year with no significant impact on agricultural output. Bircan and Saka (2018) find for Turkey that state-owned banks systematically adjust their lending in relation to local elections compared with private banks in the same province, based on electoral competition and political alignment of incumbent mayors, with negative effects for firms in opposition-dominated areas.

- The International Finance Corporation (IFC), in its comments to IEG on the draft evaluation, notes that where privatization is not immediately possible, SOE reform can, over time, help SOEs graduate from sovereign-guaranteed borrowing to borrow from the IFC (directly and through mobilization) and then graduate to commercial-only borrowing, when possible, including direct access to capital markets. The IFC also notes that SOEs are central to the development of capital markets in most emerging markets. Underperforming SOEs can potentially limit the development of strong, sustainable capital markets.

- “The MFD [Maximizing Finance for Development] approach builds on substantial cross–Bank Group experience in working with governments to crowd in the private sector to help meet development goals. MFD seeks to make this systematic. Recent examples of cross–Bank Group collaboration which have crowded in private solutions provide some important lessons.… These highlight the importance of country ownership and of upstream knowledge and advisory work in helping clients improve investment environments, the complementarity of different Bank Group interventions in transforming the sectors, and the benefits of collaboration with other development partners” (World Bank 2017a).

- In 2013, “One World Bank Group” was enshrined in the World Bank Group Strategy, which stated: “The new Strategy encompasses the concept of acting as One World Bank Group, significantly increasing collaboration across its agencies.… The One World Bank Group approach will entail joint projects managed more collaboratively than in the past” (World Bank Group, 2013).