World Bank Support to Reducing Child Undernutrition

Chapter 3 | World Bank Contribution to Nutrition Results

Highlights

The World Bank’s nutrition portfolio has improved its overall performance over time, and support to institutional strengthening and underlying determinants shows better results than support to immediate determinants. The adequacy of the enabling environment underlies the potential for a country to improve the determinants of nutrition, which in turn can improve a country’s nutrition outcomes for mother and child.

Community-based programs contribute to behavior changes that improve nutrition determinants. However, achieving sustained behavior change is challenging, and measurement of progress along the results chain is weak, undermining effective planning and evaluation to support behavior change. World Bank contributions to behaviors related to social norms are modest.

The measurement of nutrition results for projects exhibits persistent gaps, especially in tracking expected achievements from nutrition-specific and social norms interventions requiring behavior changes. Expected results from nutrition-sensitive interventions are most frequently measured, especially for those projects targeting health and family planning services, social safety nets, and agriculture and food systems.

Improving project performance in achieving nutrition results requires adequate monitoring and evaluation frameworks, sustained community-based implementation, strong government commitment and institutional capacity to support project activities, and a project design that intentionally integrates nutrition interventions that aim to improve nutrition determinants.

Nutrition Results: Project Performance and World Bank Contributions

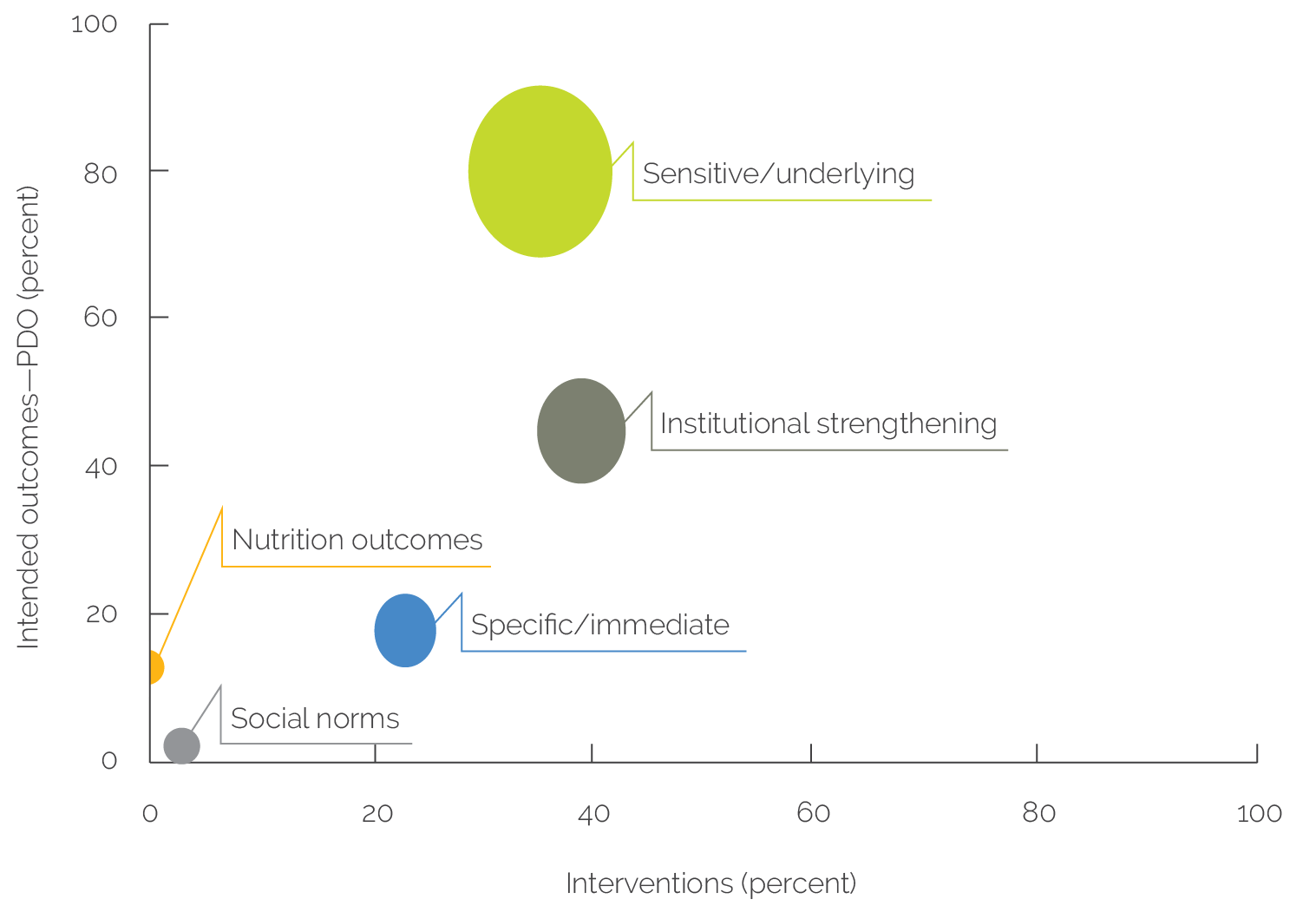

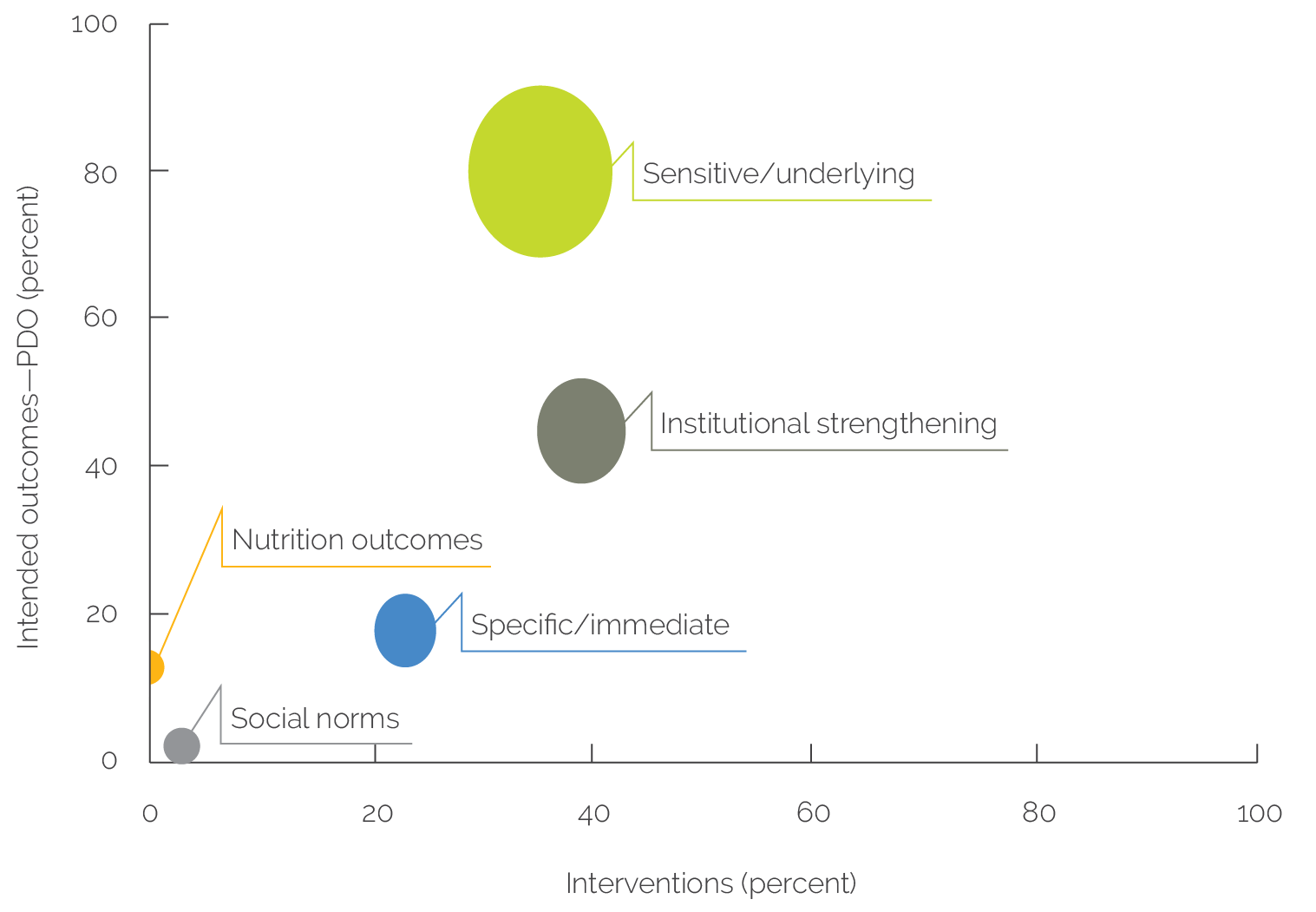

The World Bank’s nutrition portfolio overwhelmingly aims to improve the underlying determinants of nutrition and institutional strengthening in countries. This aim is consistent with the distribution of interventions that tend to concentrate at the foundations of the conceptual framework discussed in chapter 2 (figure 3.1). Social norms (women’s empowerment and early marriage and pregnancy) and to a lesser extent nutrition outcomes (anthropometric measurements, micronutrient status, and cognitive development) and immediate determinants (child feeding practices, diet diversity, and maternal and child health) are rarely part of the projects’ objectives, accounting for 2 percent, 13 percent, and 18 percent, respectively. This tendency to focus on nutrition determinants is not surprising given the relatively short duration of investment projects and the longer-term nature of nutrition outcomes and social norms.

The World Bank’s nutrition portfolio has good overall performance, but support to institutional strengthening and underlying determinants shows better results than support to immediate determinants that are more challenging to achieve. Project performance is measured by the achievement rates of results framework indicators for 131 closed projects that had relevant nutrition-related indicators across the dimensions of the conceptual framework. Overall portfolio performance is about 70 percent, which also depends on the adequacy of the results framework in terms of quality of indicators and the ambitiousness of indicators targets. Information from country case study evidence, impact evaluations, and regression analysis have also been used to assess results achieved by the portfolio.

Contributions to Institutional Strengthening

The World Bank contributes to institutional strengthening, but there is limited evidence on the continued application of knowledge gained by actors involved in training and other support to sustain change. Project performance in strengthening institutions has improved over time (figure 3.1). Overall portfolio investments in policy, service delivery, and stakeholder engagement have achieved 79 percent of the expected results. Moreover, multivariate regression analysis of the portfolio offers some evidence that successful results in institutional strengthening, and in particular policy, financing, and coordination, are associated with better achievement of nutrition outcomes and its determinants at the project level.1 In addition, the World Bank’s contribution toward stakeholder engagement (strengthening knowledge and participatory roles of networks of community volunteers, local leaders, farmers, nongovernmental organizations, and other local actors in SBCC) is also highlighted as a major factor behind project performance.2 Further, institutional strengthening emphasizes the success of the World Bank in engaging actors (90 percent), especially service providers; in improving their knowledge (83 percent); and, to a lesser extent, in applying the acquired behavior (71 percent). However, there is limited tracking of these indicators beyond the level of engaging actors and learning, and no evidence is available on whether institutional strengthening has supported sustained behavior change, such as of frontline workers to consistently apply skills to deliver services.

Figure 3.1. Portfolio Performance

Sources: Independent Evaluation Group; portfolio review and analysis.

Note: WASH = water, sanitation, and hygiene.

In-depth analysis in country case studies provides good examples of the World Bank’s contribution to strengthening institutions at national and subnational levels. Successful examples of institutional strengthening (through both ASA and lending) have included policy dialogue, leadership building, South-South knowledge exchange, evidence-based learning, support to M&E systems, and support to districts to oversee nutrition, use M&E, and strengthen extension services and community groups. A key variation across countries has been in the extent of support to policy and coordination relative to service delivery. At the national level, the World Bank has supported high-level leadership; coordination of nutrition, policies, financing, and strategies; and M&E systems, diagnostics, and research and evaluation. At the district level, it has supported learning, M&E, and supervision to oversee nutrition services. At the community level, the World Bank has strengthened the targeting of services, community groups, and extension workers (box 3.1).

Box 3.1. Contributions to Institutional Strengthening in 12 Countries

Policy, Financing, and Coordination

- Multisectoral coordination, strategies, financing, and planning. In Ethiopia, Indonesia, Malawi, Nepal, Rwanda, and Senegal, the World Bank has strengthened national nutrition coordination, policy dialogue, strategies, and planning. In Madagascar and Mozambique, however, the lack of continuity of this support across projects has limited the institutional strengthening of nutrition coordination capacities. In Senegal, the World Bank’s Nutrition Enhancement Program has improved coordination efforts by identifying areas of collaboration among sector ministries, with an emphasis on the delivery of multidimensional nutrition services in communities. In Indonesia and Rwanda, the World Bank has strengthened the multisectoral nutrition strategy, including district-level plans, and a communication strategy through a range diagnostic work on the nutrition situation, financing, and policy options. For example, the development of the National Strategy for Stunting Reduction in Indonesia and the reforms to develop the interoperability of social sector information systems in Rwanda have been catalyzed through South-South knowledge sharing supported by the World Bank on Peru’s experience in combating undernutrition.

Nutrition Service Delivery

- Strengthening decentralized and community-level interventions. In Nicaragua, the World Bank has strengthened the supervision and management capacities of local governments for the decentralized delivery of a multisector package of social services. In Madagascar, the World Bank has contributed to the refinement of community-based nutrition services through years of analytic work and advocacy. In Rwanda, the World Bank is helping in the development of community services, which engage community health workers, and the convergence of nutrition-sensitive interventions in social protection, early childhood development, and agriculture. In many countries (Ethiopia, Indonesia, Madagascar, Malawi, Mozambique, Peru, Rwanda, and Senegal), the World Bank has contributed to strengthen an integrated multidimensional package of community-based nutrition interventions. However, learning to organize sectoral and community actors to integrate the delivery of services remains a challenge.

- Monitoring and evaluation improvements. World Bank interventions in Ethiopia have helped develop nutrition surveillance capacity and geographic data. Support in Senegal has facilitated the measurement of multidimensional nutrition programs in communities. Activities in Peru have helped build capacity for the social monitoring of nutrition results. Indonesia and Rwanda are improving the accountability of service delivery by initiating village scorecard and child scorecards, which are planned to become an input into the formal management information system.

Stakeholder Engagement and Ownership

- Leadership building and stakeholder mobilization. In many countries, the engagement of government actors at all levels in nutrition strategy and planning has been instrumental for building leadership and government commitment. In Rwanda, Indonesia, and Senegal, the World Bank has supported high-level leadership and local leadership on nutrition. In Rwanda, the World Bank supports the monitoring of Imihigo, which is a contract between the president and local government leaders on achieving targets for key programs. In Indonesia, stunting summits are used to secure and sustain political leadership at national, provincial, district, and village levels, and provide a cascading system of accountability. Moreover, in most case study countries, the World Bank has strengthened social and behavior change communication to raise awareness and shape social norms at the community level. These ranged from awareness or advocacy campaigns (Bangladesh, Nicaragua, and Peru) to more intensive social mobilization programs (Madagascar, Malawi, and Senegal). Often these activities have involved multiple sectors and types of actors in communities.

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Contributions to the Immediate and Underlying Determinants of Nutrition

The World Bank makes important contributions in determinants of nutrition—with performance improving for underlying determinants and slightly declining for immediate determinants. There is more evidence of results for underlying determinants because the World Bank has invested more in nutrition-sensitive interventions over time and measurement is better. The performance of projects in achieving underlying determinants results has slightly improved over the evaluation period, and the most successful area has been agriculture and food, which has included improvements in food supply and production (vegetables, legumes, dairy products, livestock) productivity, market access, and food storage and transformation. But project achievements in immediate determinants of nutrition resulting from nutrition-specific interventions have slightly declined more recently. Although achieved results in adolescent health appear to be remarkable, that is due to a very small sample of indicators. As we have shown before, the World Bank’s attention to adolescent health interventions is limited and has considerable measurement gaps.

The World Bank has contributed to improving nutrition determinants in all case study countries. In terms of food and care, in Ethiopia, Madagascar, and Nicaragua this has included improvements in breastfeeding, child feeding, and diet. However, in most case study countries, feeding and dietary improvements are modest. Through SPJ, the World Bank has contributed in some countries to improved food consumption, parenting skills, access to health services, livelihoods, and school enrollment among lower-income households. Through Agriculture, the World Bank has improved seasonal availability of food and crops (in Ethiopia, Malawi, and Rwanda), and biofortification (in Mozambique, Nicaragua, and Rwanda). In terms of access to health, the World Bank has improved access to health services (in Ethiopia, Indonesia, Mozambique, Nicaragua, Niger, and Rwanda), including to immunizations, family planning, institutional delivery, and antenatal and postnatal care. In some countries, the World Bank has contributed to child health through expanding growth monitoring and promotion, screening, and treatment of malnourished children (in Ethiopia, Madagascar, Niger, and Rwanda). There were also gains in the prevention and treatment of childhood diseases, including diarrhea, parasitic infection, and malaria, supported by health services. Contributions to maternal nutrition are limited across countries, whereas improvements have been made in the provision of iron–folic acid to pregnant women. In terms of access to WASH, in Ethiopia, Malawi, Nicaragua, and Rwanda, the World Bank has increased access to water and sanitation, such as piped water and latrines. Community programs in Madagascar likely improved WASH behaviors. However, in Madagascar, Mozambique, and Niger the World Bank’s contribution to WASH has been modest.

Health, food, and care interventions, such as nutrition counseling, parent education, breastfeeding promotion, and support to backyard gardens, account for most behavior change results in nutrition determinants. These interventions have been quite successful in tracking evidence of actual behavioral practices, achieving 55–70 percent of behavior change indicators at the apply level and 58–72 percent of sustain level changes in the behavior of mothers or caregivers and communities.3 Still, within most projects there is a lack of tracking incremental behavior changes along a results chain of engage-learn-apply-sustain, and sustained behaviors have been less measured overall.

Community-based programs supported by the World Bank contribute to behavior changes to improve nutrition determinants, but there was limited evidence of longer-term sustained changes. The behavior change framework and process mapping have been applied in case studies to assess how behavior changes have been supported by frontline workers, community groups, and nongovernmental organizations, among other types of stakeholders. Case study evidence suggests that the World Bank has contributed to engaging actors and learning (although this is not often measured), and in some cases to new practices by caregivers, farmers, and health workers, among others, but there was limited evidence that the World Bank has contributed to longer-term sustained changes in the behaviors of actors. In most of the countries, CBN programs are still being strengthened, providing an opportunity to improve evidence and learning regarding behavior change.4

Impact evaluations of specific project investments show positive results in improving nutrition determinants. For instance, a randomized controlled trial evaluation of over 3,000 villages and 1.8 million target beneficiaries of the Generasi program in Indonesia found that community block grants to rural communities are an effective tool where the use of basic health care services is constrained not just by demand but also by supply and access. Moreover, positive impacts on the use of basic health care services have been higher in communities whose grants were linked to performance-based incentives, suggesting that the attempt of the Generasi program to replicate the conditionality of cash transfers on a community-wide level can produce positive results (Olken, Onishi, and Wong 2011).5 Another randomized controlled trial evaluation of a Total Sanitation and Sanitation Marketing program in Indonesia, when the program had been implemented at scale in rural East Java, found that sanitation improvements were largely driven by an increase in the rate of toilet construction by nonpoor households, whereas improvements remain limited for lower-income households, which are more likely to be credit constrained. Self-reported open defecation has decreased and parasitic infestations in the nonpoor sample with no sanitation at baseline has also been reduced. Diarrhea prevalence has dropped 30 percent in treatment communities compared with control communities among young children likely affected by differences in drinking water and hand washing behavior (Cameron, Shah, and Olivia 2013).

Contributions to Social Norms

The World Bank is not contributing in a substantial way to improving social norms in the nutrition portfolio. The World Bank’s nutrition portfolio gives insufficient attention to social norms interventions relating to early marriage, early pregnancy, birth spacing, and women’s empowerment (decision-making regarding childcare, food production, and health care seeking) when designing nutrition projects. The alignment of the portfolio interventions falls short in addressing social norms needs given its relative importance for achieving better nutrition outcomes. Even when social norms are supported, expected results are rarely measured, further intensifying the lack of available results. The evidence base for project-level results is very thin, encompassing only 21 indicators.

Evidence gathered through case studies also reflects the modest contributions of the World Bank toward social norms outcomes. Projects likely had some contribution in improving knowledge on sexual and reproductive health and rights and in delaying pregnancy (Ethiopia, Nicaragua, and Niger); gender roles in agriculture (Madagascar, Niger, and Rwanda); girls’ enrollment in school (Niger); and family planning usage (Ethiopia, Niger, and Rwanda). For example, Nicaragua’s support to sexual and reproductive health and rights likely helped increase contraceptive usage and reduce teen pregnancy and gender-based violence. Agriculture support has likely been particularly important to improve women’s participation in food production, storage and transformation, and livestock farming for milk and meat.

Contributions to Nutrition Outcomes

In World Bank nutrition support, the pathway to improve nutrition outcomes for mothers and children has been through support to nutrition determinants. This approach is consistent with a low emphasis of nutrition outcomes in projects’ objectives and consequently the limited measurement of nutrition outcome indicators in projects’ results frameworks. In addition to their low frequency, improvements in nutrition outcomes at project level have been much harder to achieve (53 percent) compared with immediate and underlying determinants and institutional strengthening results. Moreover, the multivariate regression analysis found that the inclusion of nutrition indicators in results frameworks (such as anthropometric measurements, micronutrient status, and cognitive development) is associated with a lower project performance.6 This finding is likely due to the time lag to see movement in these indicators, which makes it difficult to measure improvement in outcomes in the time frame of a single project.

Anthropometric measures and the micronutrients status of children under five have improved in most case study countries over the evaluation period, but these changes are more difficult to attribute to World Bank support. The prevalence of wasting and underweight has decreased in most of the countries, likely because of investments in growth monitoring and promotion and treatment of malnutrition. In countries such as Malawi and Mozambique, repeat crises likely have led to limited improvements in nutrition indicators. Indicators of stunted growth, LBW, and anemia may have decreased, but levels remain high in most of the countries. The achievement of nutrition outcomes at the country level is more difficult to attribute to World Bank support given the multiplicity of factors and development partners involved, the synergies among multisectoral interventions, and the rather longer time span for the changes in nutrition outcomes to materialize.

Impact evaluations for specific projects provide evidence on the positive impact of World Bank efforts on nutrition outcomes for target beneficiary groups. The impact evaluation of the Generasi program in Indonesia shows that nutrition outcomes for children in project implementation areas have improved compared with those of a control group. The impact was stronger in areas with higher undernutrition before project implementation, where underweight rates have declined by 8.8 percentage points (20 percent compared with control areas); severe underweight rates have dropped by 5.5 percentage points (33 percent compared with control areas); and severe stunted growth has been reduced by 6.6 percentage points (21 percent compared with control areas; Olken, Onishi, and Wong 2011). Another example is an experimental design evaluation of the ECD project for expanding access to community-based early childhood services in rural Indonesia, which has found that the project led to improvements in lower-income children’s social competence, language, cognitive development, and their emotional maturity (Brinkman et al. 2015).

Measuring Nutrition Results

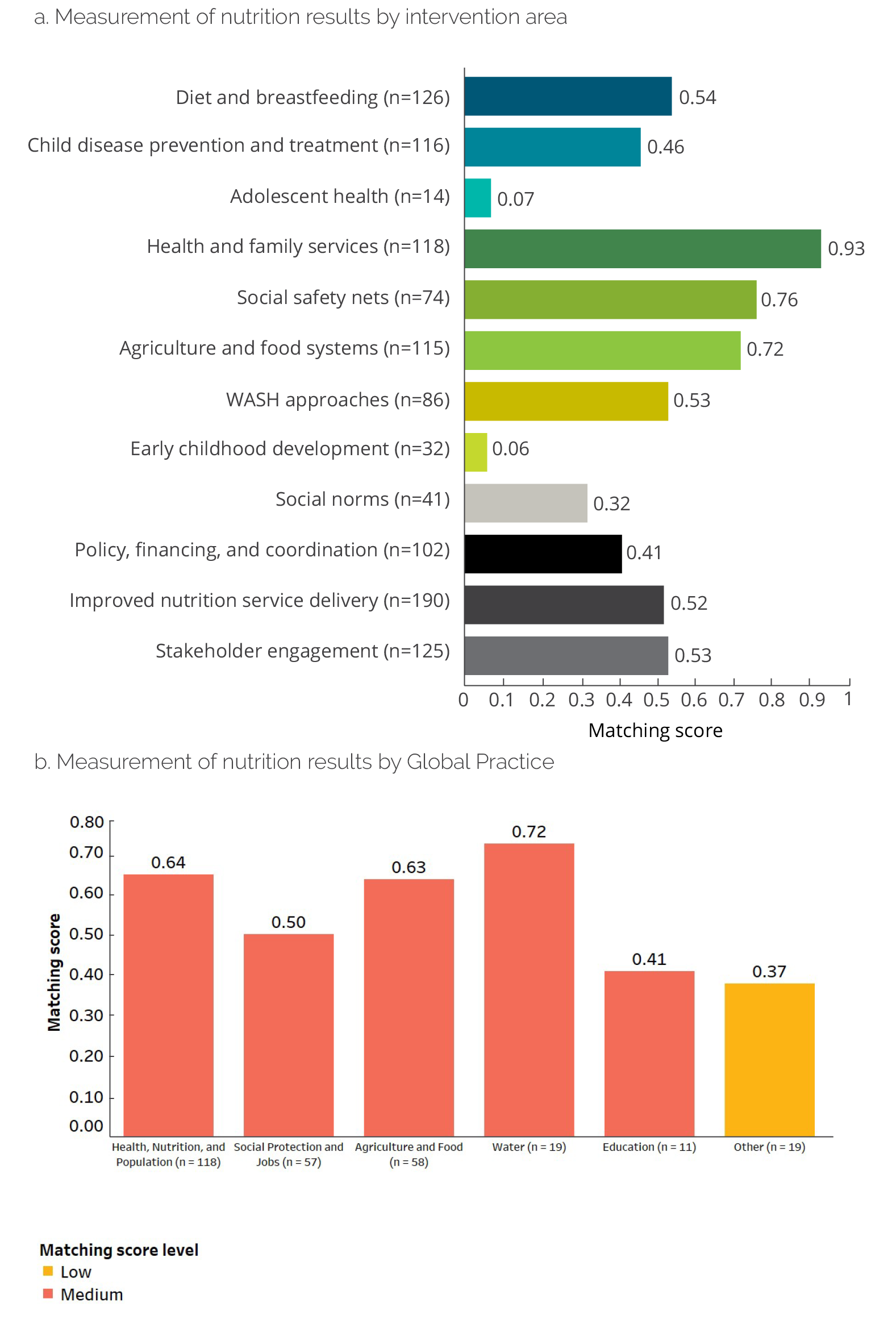

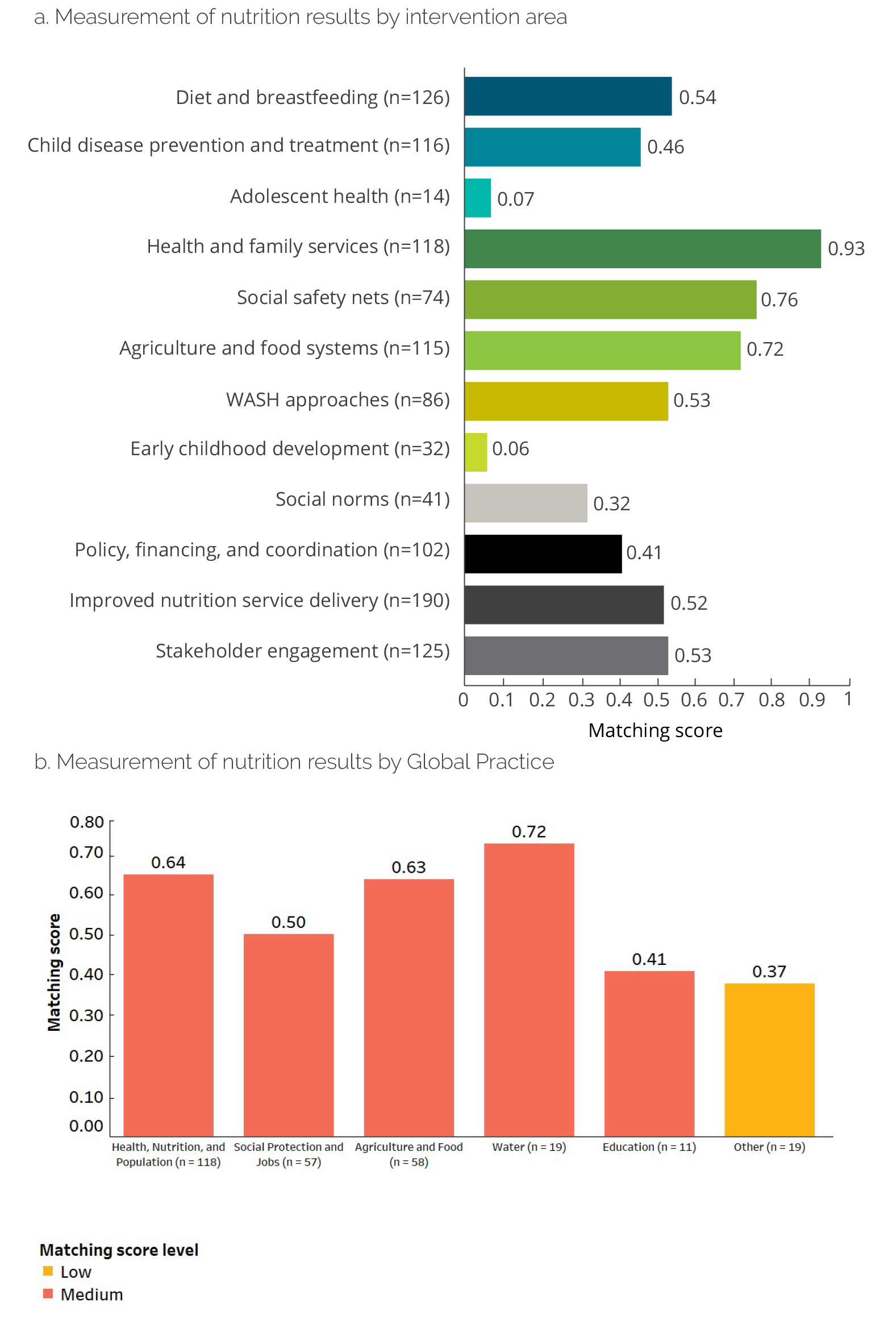

Persistent gaps exist in the measurement of nutrition-related results within projects, especially when tracking expected achievements from nutrition-specific and social norms interventions. IEG has calculated a matching score reflecting the alignment between the supported nutrition interventions and the presence of indicators to track progress on results based on a classification of more than 2,500 indicators according to the dimensions of the conceptual framework. On average, the matching score between interventions and indicators for the entire nutrition portfolio is 57 percent, and it has slightly improved over time (figures 3.2 and 3.3). Expected results from nutrition-sensitive interventions are the most frequently measured, especially in health and family planning services, social safety nets, and agriculture and food systems. The high measurement gap in social norms further intensifies the lack of available results in an area where the World Bank has not given enough attention when designing nutrition projects. Among GPs, Water, HNP, and Agriculture have most consistently tracked progress on results from their interventions.

Figure 3.2. Distribution of Interventions, Intended Outcomes, and Project Indicators

Sources: Independent Evaluation Group; portfolio review and analysis.

Note: The vertical axis represents the percentage of projects’ objectives per dimension, and the horizontal axis represents percentages of interventions. The size of each bubble represents the share of project indicators by area. PDO = project development objective.

Figure 3.3. Measurement of Nutrition Results at the Project Level

Sources: Independent Evaluation Group; portfolio review and analysis.

Note: The matching score is the share of interventions with an indicator to track progress of results in the same area. Matching score levels: Low, matching score <= 0.40; Medium, 0.40 < matching score <= 0.80; High, matching score > 0.80. The mean matching score is 0.59, the median is 0.57, the standard deviation is 0.29, and the range is 0–1. WASH = water, sanitation, and hygiene.

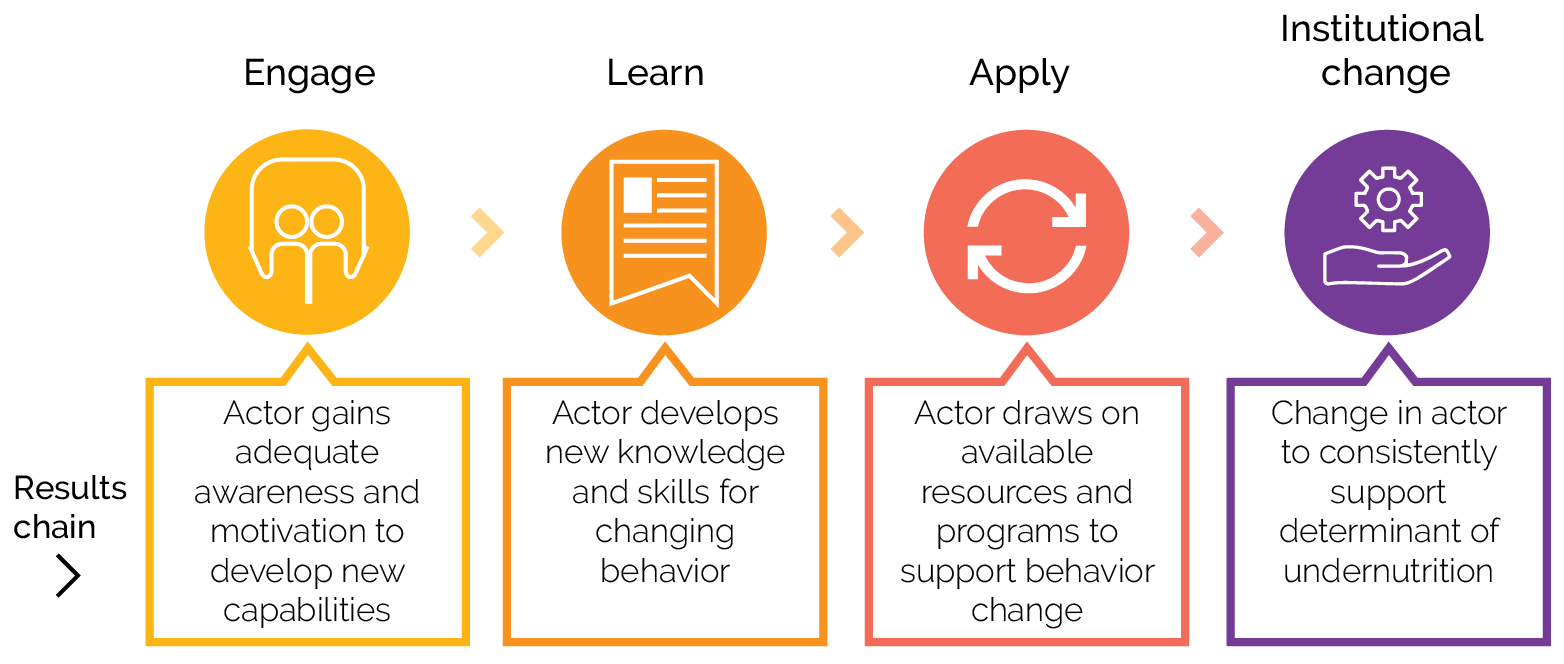

Similarly, weak measurement of the progression along the behavior change results chain hinders effective planning and evaluation. IEG has developed a framework and process map that traces evidence of behavior changes across different actors along the engage-learn-apply-sustain results chain (figure 3.4). The goal of behavior change interventions is to engage different actors to induce sustained practices in the long run. However, when tracking evidence of behavior change results, World Bank projects rarely follow the results chain, leading to an incomplete monitoring of change processes. Moreover, many projects do not measure behavior changes. For projects that measured behavior changes, they most often measured the apply level (43 percent), followed by the engage (23 percent), learn (14 percent), and sustain (23 percent) levels. For example, the case study found evidence of behavior change, although it was not always measured in the project indicators (appendix G). The behavior change map for Nicaragua shows that to improve access to food and care, at the engage level, parents were engaged by nutritionists and promoters in communities; at the learn level, parents learned to prepare new foods and learned practices for caregiving of children; at the apply level, families increased their consumption of a variety of foods, and women and children increased the number of food groups consumed; at the sustain level, there was no evidence available on sustained diet diversity.

Figure 3.4. Tracing Evidence of Behavior Change Levels in Actors

Sources: Independent Evaluation Group; behavior change analysis.

Explaining Nutrition Results: Successes and Failures behind Project Performance

Effective pathways to improve project performance in achieving nutrition results are improving M&E of determinants across sectoral areas, community-based implementation, country ownership, and designing projects to address nutrition determinants and to strengthen country coordination capacity. Based on analysis of Implementation Completion and Results Reports, Implementation Completion and Results Report Reviews, and Project Performance Assessment Reports of closed projects, IEG has identified nutrition-relevant factors behind the success or failure in achievement of nutrition results. Unsupervised hierarchical clustering machine learning algorithms have been used to build a taxonomy of factors emerging from the text of project documents, suggesting that project failure factors are the reverse or absence of success factors in the nutrition portfolio.7

Successful projects had M&E frameworks that measured the expected contribution to nutrition determinants across sectoral areas. Important was measuring indicators that were related to nutrition determinant in a theory of change, such as feeding practices, micronutrient supplementation, and use of nutrition-sensitive services; that were at a geographical level supported by the project, such as the community level, rather than nationwide; that measured changes that could be observed in the project time frame and at different levels of the results; that measured the expected achievements of a range of interventions supported by the project; that had a number of sources for routine (such as administrative data) and periodic data collection (such as population surveys and operational research studies), which could be triangulated to review progress; and that included indicators to measure the quality of services. Moreover, as observed in the country stocktaking (appendix H), the strengthening of the multisectoral collection of M&E data on nutrition interventions has been critical for implementation monitoring in Malawi, Peru, Rwanda, and Senegal.

Successful projects have a strong community-based implementation, which is also key to induce behavior changes that improve nutrition determinants. The strength of community engagement, participation, and leadership in implementing nutrition interventions; support for capacity building in communities for selecting and managing local subprojects; and collaboration between communities and local partners in delivering social services matter for the achievement of nutrition results. This evaluative finding is consistent with multivariate regression estimates.8 For example, community participation has been key for a project in Burundi that sought to strengthen the capacities of local community groups to work together in selecting, implementing, financing, and monitoring and maintaining priority community services. Project implementation has included timely contribution by beneficiaries to subproject costs so that they would own the subprojects and be very much involved in their maintenance and continued operation.

Other important factors explaining projects’ success are country ownership and having a design to reinforce existing country structures and to develop country coordination capacity for nutrition. This includes supporting government commitment to nutrition and aligning projects to develop institutional capacity for nutrition in terms of coordinating adequate financing, supporting nutrition-related reforms, the availability and commitment of a skilled workforce to support nutrition, and developing the capacity of line ministries and executing agencies to coordinate action and service delivery. A project in Senegal that sought to reduce nutrition insecurity of children under five by expanding the country’s National Enhancement Program, for instance, has seen that the institutional setup in the prime minister’s office has enhanced coordination of the policy dialogue among multiple stakeholders and sectors. This has increased stakeholders’ shared responsibility of the observed nutrition-related problems, which in turn has contributed to the enhanced uptake of services.

The intentional design of interventions to support results in nutrition determinants matters for project success and is often better in projects with a heavy focus on nutrition than in sectoral projects. Where interventions are integrated in sectoral projects with few nutrition interventions, the design of support to achieve expected results in nutrition determinants is often weak. Multivariate regression analysis found that sectoral projects that integrated a few nutrition interventions had a lower achievement of nutrition outcomes and determinants when they planned interventions beyond their area of expertise, but projects that were designed with a heavy nutrition focus were able to contribute to results for nutrition determinants across a range of sectors. In case study countries, interventions integrated in Agriculture and Water projects have often lacked an intentional design to improve nutrition determinants, such as access to nutritious foods or hygiene and sanitation practices of households with children.

The use of diagnostics to inform project design and evidence-based policies contributes to project success in achieving nutrition results and is particularly important in multisectoral approaches toward reducing undernutrition for country programs and policy. In Rwanda and Indonesia, a nutrition situation analysis, rapid mapping on nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive interventions, and nutrition public expenditure review have supported the government in developing its multisector strategy and identifying needs to improve nutrition financing for multisectoral coordination. Consistently, regression analysis has found a strong positive association between project performance and the use of diagnostic and analytical work at project design. Although some countries (Ethiopia, Indonesia, and Rwanda) have better leveraged a mix of knowledge activities to help strengthen the nutrition results of both projects and the country’s program, countries’ support seldom strategically balances analytical work, knowledge sharing, and leadership building for improving evidence-based policies and nutrition programming. For example, in Mozambique, although services have been emphasized, attention to relevant analytical work, support to leadership, knowledge sharing, and coordination activities has been limited. Moreover, although Madagascar has done extensive evidence learning to develop its services, less support has been given to develop leadership, policies, and coordination of nutrition.

Over the years, a clear consensus has grown that the key to solving child undernutrition is multidimensionality in programming. Countries with a World Bank project portfolio that has a mix of nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive interventions and institutional strengthening provide a pathway to improve nutrition determinants and contribute to outcomes. Regression analysis offers some evidence that multidimensional country portfolios, having a mix of nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive interventions, are slightly positively associated with project performance. But strengthening the World Bank’s within-country alignment and targeting of relevant interventions to address disaggregated needs or priorities is key, and case studies showed that projects in different GPs have been mostly implemented in different geographical areas and target groups, and they lacked mechanisms to integrate or converge actions or build on respective achievements to improve nutrition outcomes in the same communities. Although learning to integrate or converge the implementation of interventions of different sectors in the same geographical areas is emerging in countries, the World Bank needs to improve coordination across GPs in the implementation of interventions. Multidimensional projects offer one approach to overcome coordinated targeting challenges, but they do not perform better on average than those focusing on a narrow set of intervention areas. Moreover, noncore nutrition projects that integrate a small nutrition component tend to perform worse in achieving nutrition results in areas that are not related to their sectors.

- See appendix I on multivariate regression analysis for more details.

- See section on factors of success and failure in project performance in appendix D.

- See table C.1 for examples of behavior change indicators at the engage-learn-apply-sustain levels.

- See table G.3 for behavior change assessment in selected countries.

- The Generasi program target health indicators are (i) four prenatal care visits; (ii) taking iron tablets during pregnancy; (iii) delivery assisted by a trained professional; (iv) two postnatal care visits; (v) complete childhood immunizations; (vi) adequate monthly weight increases for infants; (vii) weighing monthly for children under three and biannually for children under five; and (viii) vitamin A twice a year for children under five.

- See appendix I on multivariate regression analysis for estimation results.

- The emerging taxonomy of factors has been reviewed and validated by the evaluation team. See appendix D for the complete taxonomy of success and failures factors.

- See appendix I on multivariate regression analysis.