World Bank Support for Public Financial and Debt Management in IDA-Eligible Countries

Chapter 1 | The World Bank and the Management of Public Finance

Sound public finance management is critical to the achievement of the World Bank Group’s goals of eradicating extreme poverty and promoting shared prosperity. It is critical to fiscal discipline and the efficient and effective use of scarce public resources to deliver public services. Weaknesses in the management of public resources can have wide-ranging implications for development, including by driving a wedge between public policy and its implementation. The importance of sound public financial management (PFM) has been elevated with the onset of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic as policy makers face rising demands for public support and services in the face of reduced revenues.

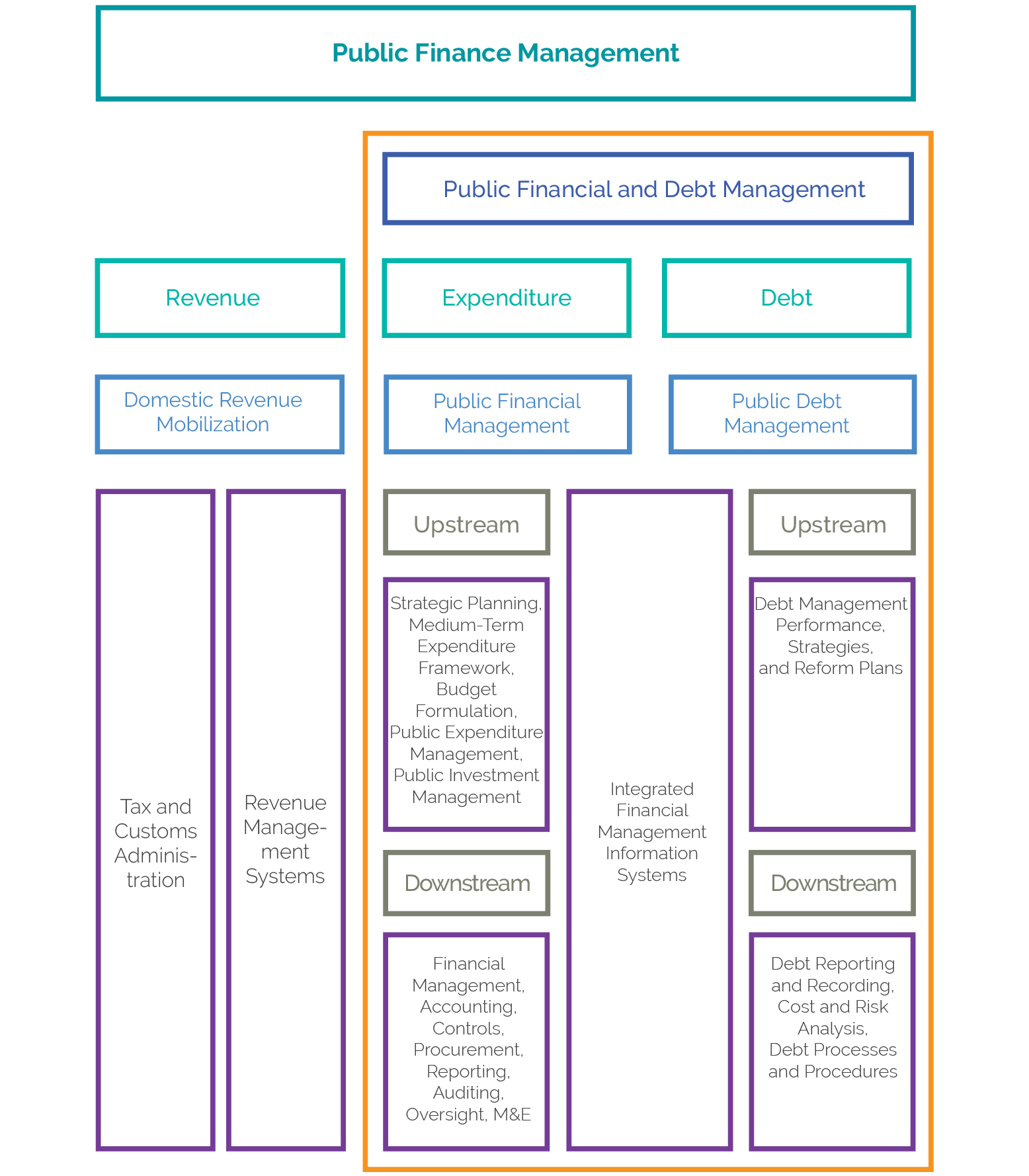

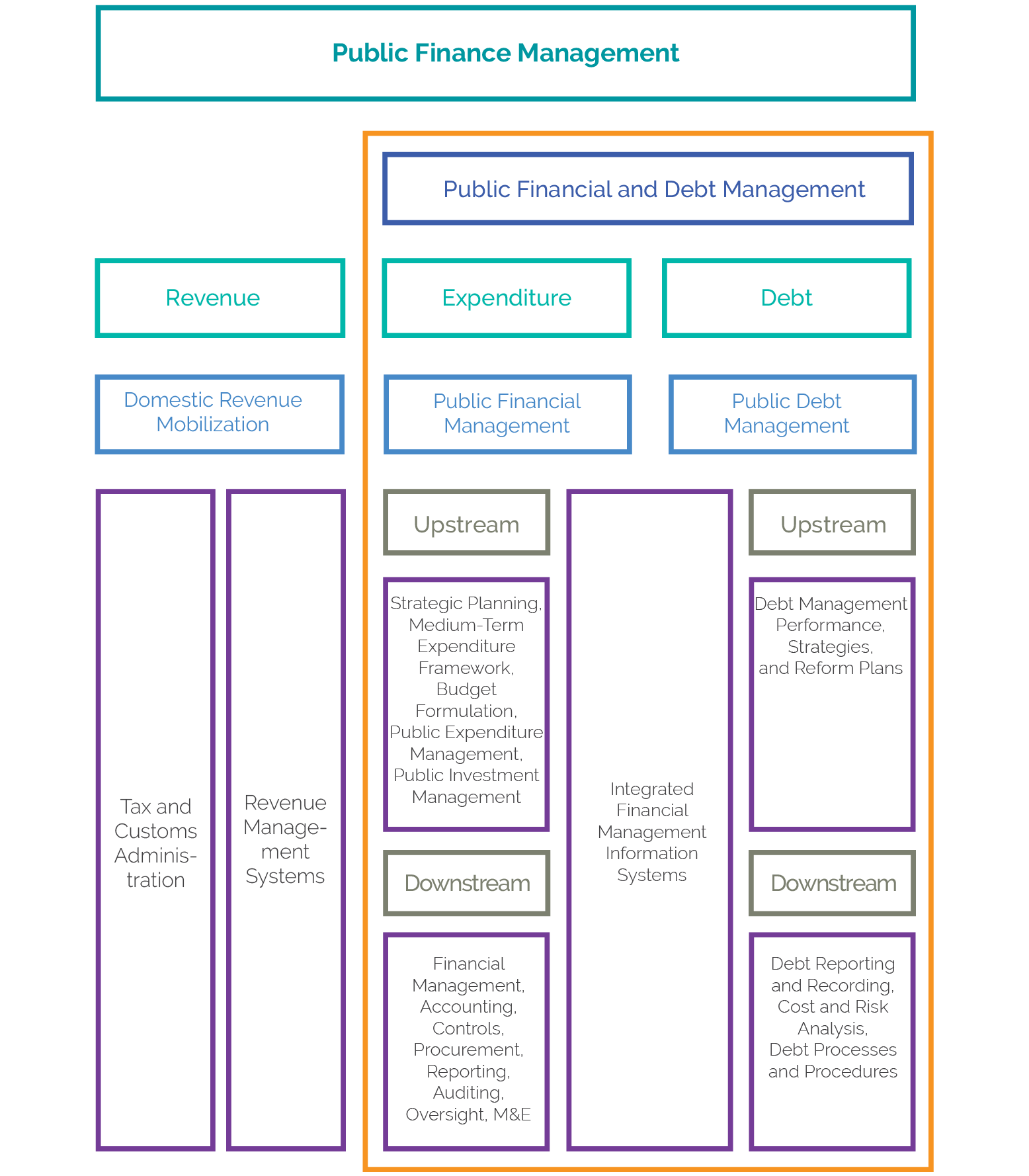

For this evaluation, public finance management is an umbrella concept that captures the processes and institutions used to implement fiscal policy while providing critical information to inform policy making. The key elements of public finance management are (i) revenue administration, (ii) PFM,1 and (iii) public debt management (PDM). This evaluation is focused on the last two elements; revenue administration is the subject of a parallel Independent Evaluation Group (IEG) evaluation, World Bank Group Support for Domestic Revenue Mobilization.

The World Bank helps International Development Association (IDA)–eligible client countries strengthen the management of public finance through a variety of channels and using a variety of instruments. The channels include support to (i) improve the efficiency, effectiveness, and equity of revenue collection; (ii) establish and strengthen systems for budget preparation and management (including public expenditure management [PEM]), public sector accounting, public investment management (PIM), and internal and external accountability; and (iii) build capacity to manage government assets and liabilities efficiently, including for macroeconomic policy and fiscal risk management. This support is delivered by IDA in a variety of forms, including through investment projects, development policy operations (DPOs), advisory services and analytics (ASA) activities, training, technical assistance, and diagnostics.

The World Bank approach to the management of public finance can be seen in the World Development Report 1988 on public finance in development (World Bank 1988). The report covered a broad range of public finance issues involving both policy formation and implementation: the use of fiscal policy for stabilization and adjustment, tax systems, the allocation of public spending, the financing of local governments, and the reform of state-owned enterprises. The approach was adapted over time, as seen in the World Development Report 1997: The State in a Changing World (World Bank 1997), which recognized the primacy of institutions in development (that is, the rules and customs that determine how economic technical inputs are used). More recent strategy papers have placed greater focus on anticorruption and developing “good fit” institutions adapted to local conditions. These include Reforming Public Institutions and Strengthening Governance (World Bank 2000), Strengthening World Bank Group Engagement on Governance and Anticorruption and its 2012 update (World Bank 2007, 2012b), and The World Bank’s Approach to Public Sector Management 2011–2020 (World Bank 2012c). Even more recently, the World Development Report 2017: Governance and the Law, went a step further to position institutions as the principal factor for success of governance-oriented reforms (World Bank 2017c).

Building the capacity of country clients to manage public finance is important to the fulfillment of the World Bank’s mandate. After shifting its attention to poverty eradication during the 1970s, the World Bank came to strongly emphasize support to improve the institutions and systems of public finance management during the early 1980s, as developing economies struggled with macroeconomic stability and debt sustainability challenges. During the 1980s and 1990s, the World Bank increasingly recognized the importance of institutional development—including for the management of public finances—as a key complement to the policy reforms it supported through adjustment lending.2 By the time the World Bank shifted from adjustment to development policy lending—with a new operational policy introduced in September 2004—supporting clients to strengthen the management of public finance accounted for a large share of the policy reforms supported by the World Bank (Koeberle, Stavreski, and Walliser 2006).

Support for public finance management from the World Bank is particularly important to IDA-eligible countries. This was recognized by the IDA Deputies and reflected in their report for the 19th Replenishment of IDA to the IDA Board of Governors: “The first challenge is to assist IDA countries to ensure that the benefits exceed the costs of servicing their debt. IDA and other partners can help by supporting initiatives that enhance capacity in areas such as public finance management, public investment management including project screening and implementation, adoption of good procurement practices, and debt management” (IDA 2020a, 19).

IDA-eligible countries need to make the most of their resources if they are to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. Such measures need to reflect the countries’ significant development needs, historically limited access to global capital markets, and weak domestic resource mobilization. At the same time, World Bank attention to public finance management reflects a desire on the part of creditors—multilateral, bilateral, and commercial—to avoid a repeat of the extensive assistance provided to many low-income countries in the context of the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) Initiative and the Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative (MDRI), although, given the need to address the significant economic and social challenges of COVID-19, the accrual of more debt is inevitable. To avoid a resurgence of debt and ensure that resources freed up from debt service are channeled into productive, growth-enabling spending, the World Bank and development partners have paid particular attention to public financial and debt management (PFDM) capacity building after debt relief, with much of the support being provided through the multidonor Debt Management Facility (DMF) (World Bank 2019).

Evaluation Scope

This evaluation assesses the effectiveness of World Bank capacity-building support (to institutions, systems, and human capital development) to IDA-eligible countries between fiscal year (FY)08 and FY17 in two subthemes of public finance management: PFM and PDM (figure 1.1).

- PFM refers to the areas of budget formulation, planning, and execution (including predictability and control); public sector accounting; institutional accountability and transparency; external oversight of public finances; and systems and processes to enhance the efficiency and integrity of public spending and investment.

- PDM refers to aspects of public sector debt management such as coordination with macrofiscal policies; monitoring, reporting, and recording of public and publicly guaranteed debt; and provision of information to policy makers on how to meet financing needs at a low cost and with a prudent degree of risk while ensuring overall debt sustainability.

The evaluation universe includes the 85 client countries eligible for IDA for at least two years during the evaluation period (FY08–17). Nine current (FY21) International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD) countries were IDA eligible for at least two years during the evaluation period: Azerbaijan (graduated in FY11); Angola, Armenia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Georgia, and India (graduated in FY14); and the Plurinational State of Bolivia, Sri Lanka, and Vietnam (graduated in FY17). For the entire list of countries, see appendix B.

This evaluation excludes subthemes of public finance management that are being or have been addressed by other IEG evaluations. Revenue administration and management—the third pillar of public finance (revenue, expenditure, and debt), which includes support for both tax and customs administration—is being evaluated separately through the forthcoming IEG evaluation World Bank Group Support for Domestic Revenue Mobilization (see also World Bank 2017d). Fiscal decentralization and subnational PFM is being evaluated through the forthcoming IEG evaluation World Bank Group Engagement on Strengthening Subnational Governments. Countercyclical spending and related interventions have been previously evaluated, including in the World Bank reports The World Bank Group’s Response to the Global Economic Crisis (2010) and Crisis Response and Resilience to Systemic Shocks (2017b). Procurement reform was evaluated by IEG in The World Bank Group and Public Procurement (World Bank 2014a).3 This evaluation only covers support provided by the World Bank; neither the International Finance Corporation nor the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency are significantly involved in PFDM.

Figure 1.1. Elements of Public Finance Management

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: M&E = monitoring and evaluation.

The effectiveness of PFDM is influenced by a wide range of factors (figure 1.2), technical and otherwise, many of which are outside of the World Bank’s control. This evaluation focuses on World Bank lending and nonlending support to build and improve the accountability systems of checks and balances, taking into account the efforts of development partners and the domestic and global context (namely global trends and events, the political economy, local conditions, and external shocks and factors such as the COVID-19 crisis). In debt management, issues of domestic debt market development and macroeconomic policy are also outside the scope of the evaluation. Although the World Bank is a leading provider of support for PFDM in IDA-eligible countries, other development partners—particularly the International Monetary Fund (IMF) but also regional development banks and bilateral partners—also provide support on PFDM either in parallel or in collaboration with the World Bank (figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2 Factors Influencing Public Financial and Debt Management and Its Impact

Figure 1.2 Factors Influencing Public Financial and Debt Management and Its Impact

Evaluation Approach and Methodology

The objective of this evaluation is to assess the success of the World Bank’s contributions to building PFDM capacity in support of improved transparency, accountability, and fiscal sustainability in IDA-eligible countries from FY08 to FY17. It seeks to identify trends in the PFDM portfolio and draw conclusions about the impact of World Bank interventions, while nonetheless acknowledging that the World Bank does not bear sole responsibility for PFDM outcomes in client countries. The evaluation makes recommendations to improve the effectiveness of PFDM capacity-building support provided by the World Bank.

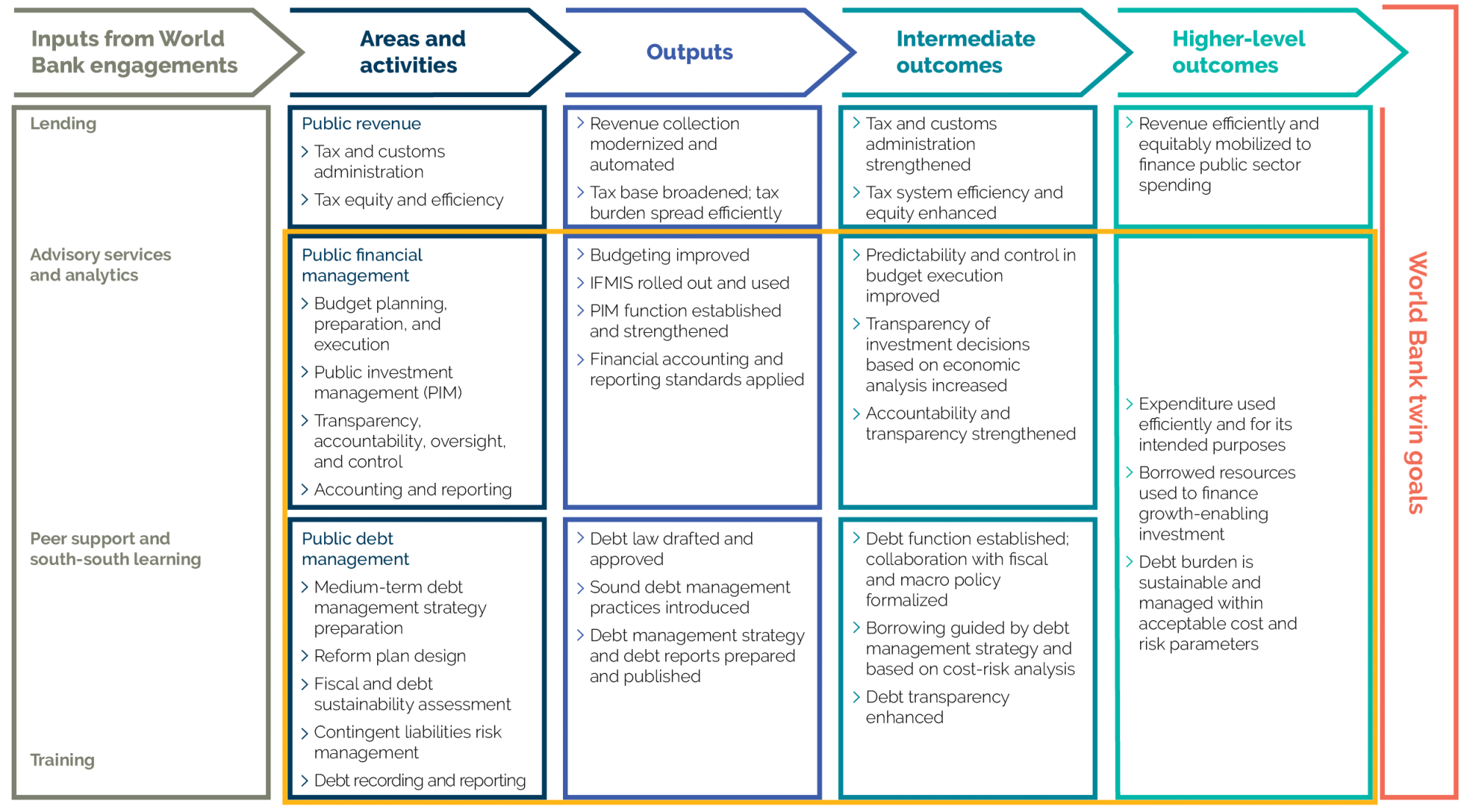

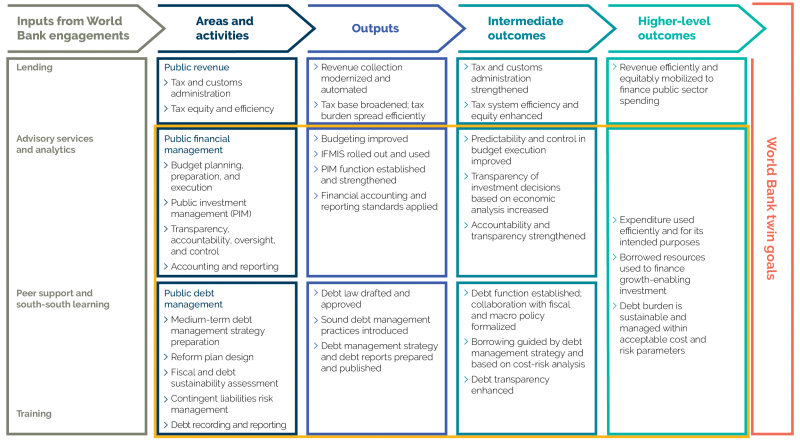

The theory of change tracing World Bank support for PFDM to improved outcomes is described in figure 1.3. It should be noted that World Bank–provided PFDM support is situated in the larger sphere of support for public finance management, including that provided by IMF and other development partners. PFDM is the main contributor to government stewardship of public resources, enabling efficient, effective, and accountable use and management of resources for development.4 In this way, PFDM contributes to the World Bank’s twin goals of ending extreme poverty and promoting shared prosperity.

Figure 1.3. World Bank Public Finance Management Capacity-Building Theory of Change

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: IFMIS = integrated financial management information system.

The report poses two sets of evaluation questions (see appendix A).

- Question 1: How relevant was the World Bank’s lending and nonlending support to building PFDM capacity in IDA-eligible countries?

- How relevant was World Bank support for PFDM to country fiscal and development needs and priorities?

- Did interventions to improve PFDM take into account existing technical capacity, and were they appropriate given underlying political and institutional constraints?

- Question 2: How effective were World Bank interventions in building PFDM capacity at the country level? What worked best and why? What did not work well?

- How effectively were the World Bank’s suite of lending and nonlending instruments applied in support of relevant PFDM-related objectives?

- How effectively did the World Bank collaborate with development partners in supporting client needs?

An evaluation of the effectiveness of World Bank PFDM support poses several methodological challenges:

- PFDM reforms require significant institutional development, which generally takes several years to take root. As many World Bank interventions—particularly policy-based lending—are shorter term in nature, the results of efforts may not emerge for several years after the intervention.

- Results indicators to measure the effectiveness of PFDM interventions are often not readily available without a formal PFDM monitoring framework. Standard diagnostics tools for assessing PFDM (for example, Public Expenditure and Financial Accountability [PEFA] and Debt Management Performance Assessments [DeMPAs]) are not applied on a regular basis and are insufficient by themselves to assess World Bank effectiveness. And even when they are applied regularly, they can lack the granularity necessary to track progress, particularly at lower levels of capacity. This is particularly problematic for monitoring improvements in PFDM for IDA-eligible countries (see box 1.1). These shortcomings are both limitations on the analysis in this evaluation and one of its findings.

- The implementation of PFDM reforms and their sustainability is highly dependent on a wide range of nontechnical factors, including political ownership, electoral cycles, independence of the civil service from political influence, and high civil service turnover, and can therefore be subject to swift reversals as governments change or trained technical staff leave for better-paying jobs in the private sector.

- Other multilateral institutions (for example, IMF and regional development banks) and bilateral donors provide similar or complementary support for PFDM to that provided by the World Bank. This complementary support has the potential to enhance the impact of World Bank support, which inevitably presents challenges in attributing the results of PFDM support to any single provider.

Box 1.1. Indicators Used to Measure Public Financial and Debt Management Performance

The evaluation used several public financial and debt management indicators to gauge performance, including the following:

- Country Policy and Institutional Assessments. The World Bank conducts annual Country Policy and Institutional Assessments for all borrowing countries. The assessment is composed of 16 criteria, grouped in four clusters: (i) economic management, (ii) structural policies, (iii) policies for social inclusion and equity, and (iv) public sector management and institutions. World Bank staff conduct the assessments, scoring criteria on a scale from 1 (low) to 6 (high). Criteria focus on policies and institutional arrangements—the key elements that are within a country’s control—rather than on actual outcomes, which are influenced by elements outside the country’s control. Two criteria are relevant for the public financial and debt management evaluation: debt policy and management, and quality of budgetary and financial management. Country Policy and Institutional Assessments scores are designed to allow for cross-country comparisons and comparison over time. One limitation of the data, however, is that subscores for the dimensions of each criterion are not publicly disclosed.

- Public Expenditure and Financial Accountability (PEFAs) assessments. The PEFA assessment measures performance over time using a set of high-level indicators that measure the performance of public financial management systems, processes, and institutions. PEFA assessments are generally conducted every four or so years by the World Bank or a development partner, with the support of client governments. Although most PEFA assessments are disclosed, not all are made public. PEFA indicator scores reflect a number of dimensions, which are scored on a four-point, ordinal scale—A, B, C, or D—according to criteria established for each dimension. To conduct quantitative analyses, the Independent Evaluation Group (IEG) used the PEFA Secretariat’s crosswalk, which allows users to convert alphabetic scores into numerical values for this purpose (with A being 4.0, B being 3.0, C being 2.0, and D being 1.0).PEFA indicators are meant to be compared within one country over time (and not across countries). To allow for longitudinal analysis, IEG looked only at the 41 countries within the evaluation universe that had at least two PEFA assessment scores during the evaluation period. However, some assessments were missing indicator scores, further limiting the number of observations. Although the PEFA methodology was altered in 2016, this evaluation (fiscal year 2008–17) only looked at those assessments that used the 2011 framework.

- Debt Management Performance Assessments (DeMPAs). The DeMPA is a World Bank diagnostic tool to assess the quality of government debt management practices and institutions. Through a comprehensive set of 15 debt performance indicators, organized into five areas and spanning the full range of government debt management functions, DeMPAs help identify areas for reform and guide the strengthening of debt management capacity, processes, and institutions. Repeat DeMPAs help governments monitor progress toward sound debt management practices.DeMPAs are treated as confidential, requiring the approval of the government for publication. Although World Bank staff are now actively encouraging DeMPA publication, the findings of many DeMPAs remain unavailable to the public and to development partners.Modeled on the PEFA framework, DeMPAs allow for longitudinal data analysis. Debt performance indicators are rated on a four-point ordinal scale (A, B, C, or D, converted into numerical values in the same manner as PEFA scores). However, DeMPA scores lack granularity, particularly at lower levels, which can constrain the assessment’s ability to register progress achieved by countries that do not meet the minimum standard (that is, a “D”). This is particularly problematic for low-capacity countries, many of which are International Development Association–eligible and thus part of the evaluation universe. It is expected that upcoming reforms to the DeMPA methodology will address this shortcoming.

- IEG project and operation performance ratings. IEG validates World Bank staff evaluations of projects and operations through Implementation Completion and Results Report Reviews or conducts its own in-depth evaluations (including through Project Performance Assessment Reports). Performance ratings assess the extent to which projects and operations have achieved their development objectives. Subratings assess World Bank performance in project design and implementation and the extent to which the project or operation objectives are relevant to the country context. IEG produces Implementation Completion and Results Report Reviews for all World Bank lending engagements; Project Performance Assessment Reports are prepared for approximately one-fifth of lending engagements.

This evaluation augments portfolio- and intervention-level analysis with several case studies (table 1.1). Chapter 1 describes the context and scope of the evaluation. Chapter 2 provides a brief description of the World Bank’s portfolio of PFDM support for IDA-eligible countries. Chapters 3–6 present findings from an in-depth analysis of the PFDM portfolio, interventions, and country case studies organized around four central pillars of PFDM: PEM, PIM, integrated financial management information systems (IFMISs), and PDM. Findings, lessons, and recommendations follow in chapter 7. Methodological approaches are described in appendix A.

Table 1.1. Evaluation Case Studies

|

Region |

Country |

Lending Intensity |

ASA Intensity |

FCS |

HIPC |

||

|

High |

Low |

High |

Low |

||||

|

AFR |

Burkina Faso |

x |

x |

No |

Yes |

||

|

Ghana |

x |

x |

No |

Yes |

|||

|

Sierra Leone |

x |

x |

Yes |

Yes |

|||

|

EAP |

Vietnama |

x |

x |

No |

No |

||

|

ECA |

Georgiab |

x |

x |

No |

No |

||

|

LAC |

Honduras |

x |

x |

No |

Yes |

||

|

SAR |

Afghanistan |

x |

x |

Yes |

Yes |

||

|

Bangladesh |

x |

x |

No |

No |

|||

Source: Independent Evaluation Group.

Note: Bold countries represent field visits conducted for the evaluation. AFR = Africa; ASA = advisory services and analytics; EAP = East Asia and Pacific; ECA = Europe and Central Asia; FCS = fragile and conflict-affected situation; HIPC = heavily indebted poor countries; LAC = Latin America and the Caribbean; SAR = South Asia.a. Vietnam graduated from the International Development Association in the last year of the evaluation period (fiscal year 2017).b. Georgia graduated from the International Development Association in fiscal year 2014.

Context

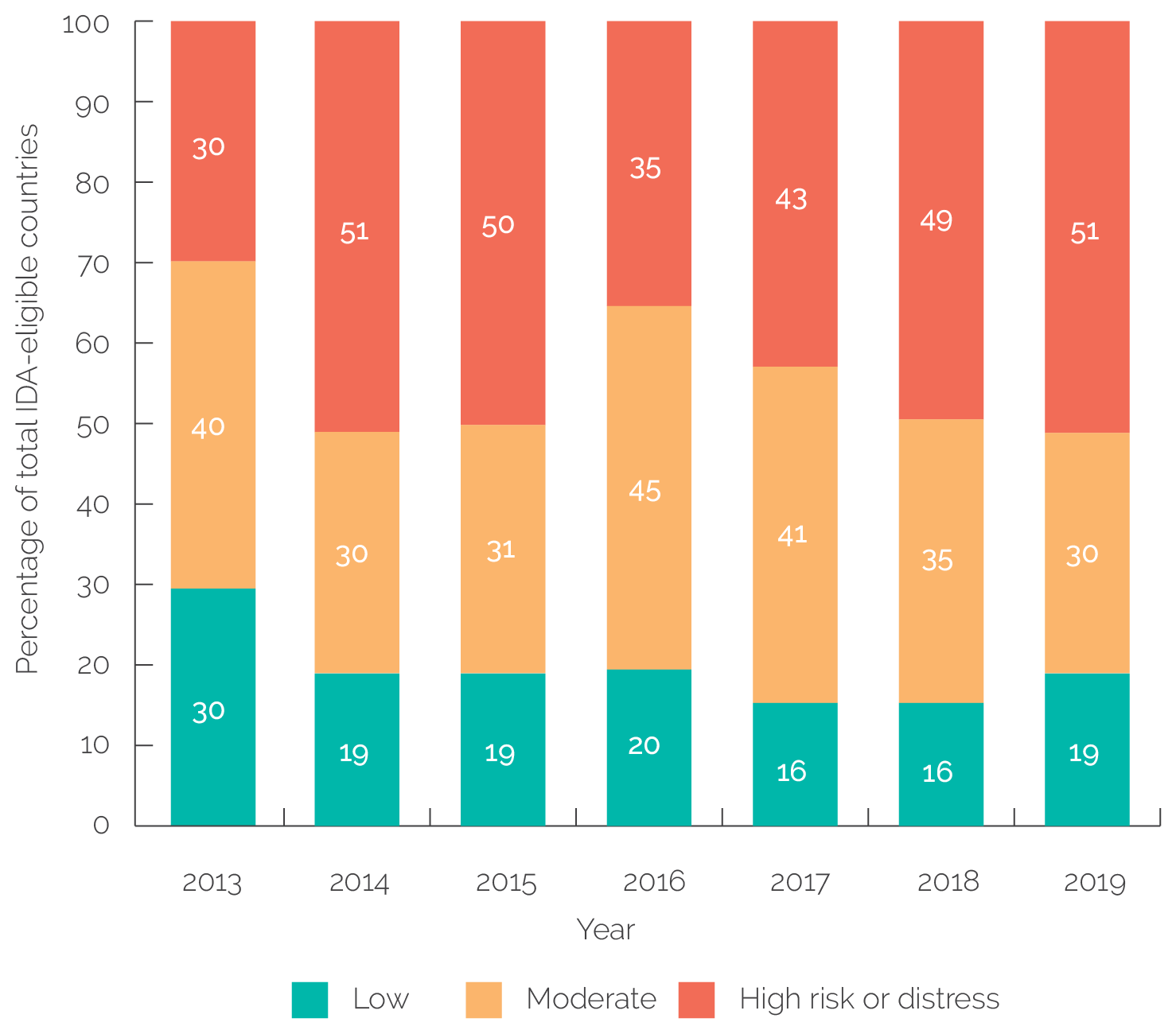

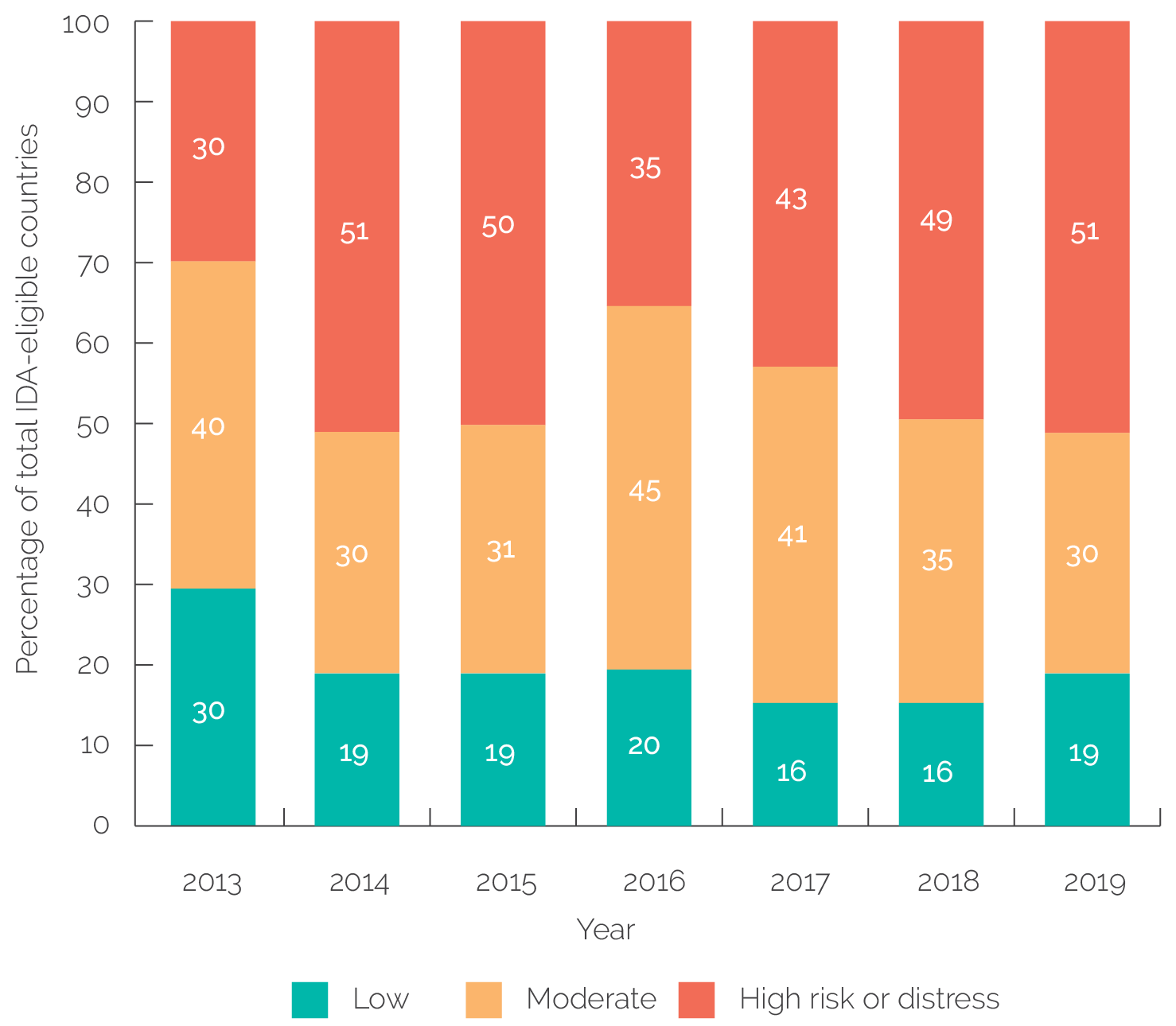

Although extensive PFDM assistance was provided to IDA-eligible countries, many still experienced a significant elevation of their risk of debt distress. Indeed, although many IDA-eligible countries remain at low or moderate risk of debt distress, the number at high risk or in debt distress increased from 13 in 2013 to 34 (of 85) by the end of July 2019 (figure 1.4). The reasons for this increase are numerous: After the global financial crisis of 2008–09, many IDA-eligible countries took advantage of their newly acquired fiscal space, historically low global interest rates due to abundant liquidity, and investor search for yield to engage in commercial borrowing and domestic debt issuance (figure 1.5).5 Much of the increased borrowing was nonconcessional and shorter term in nature (see, for example, World Bank 2013b). At the same time, many IDA-eligible countries engaged in extensive bilateral borrowing (often on opaque terms) to finance “growth-enhancing” public spending and investment, particularly in infrastructure. With varying capacities to identify and design quality investments and effectively manage their implementation, some investments fell short of growth aspirations, contributing to significant increases in debt-to-gross domestic product (GDP) ratios. This suggests a link between the quality of PIM and rising debt distress in many IDA-eligible countries. The emergence of COVID-19 and the resulting impact on economies across the globe has increased the salience of these issues and resurfaced concerns with the quality of debt management, sovereign defaults, debt restructuring, and debt relief.

Figure 1.4. Risk of Debt Distress in International Development Association–Eligible Countries

Source: Independent Evaluation Group; World Bank Debt Sustainability Analysis.

Note: IDA = International Development Association.

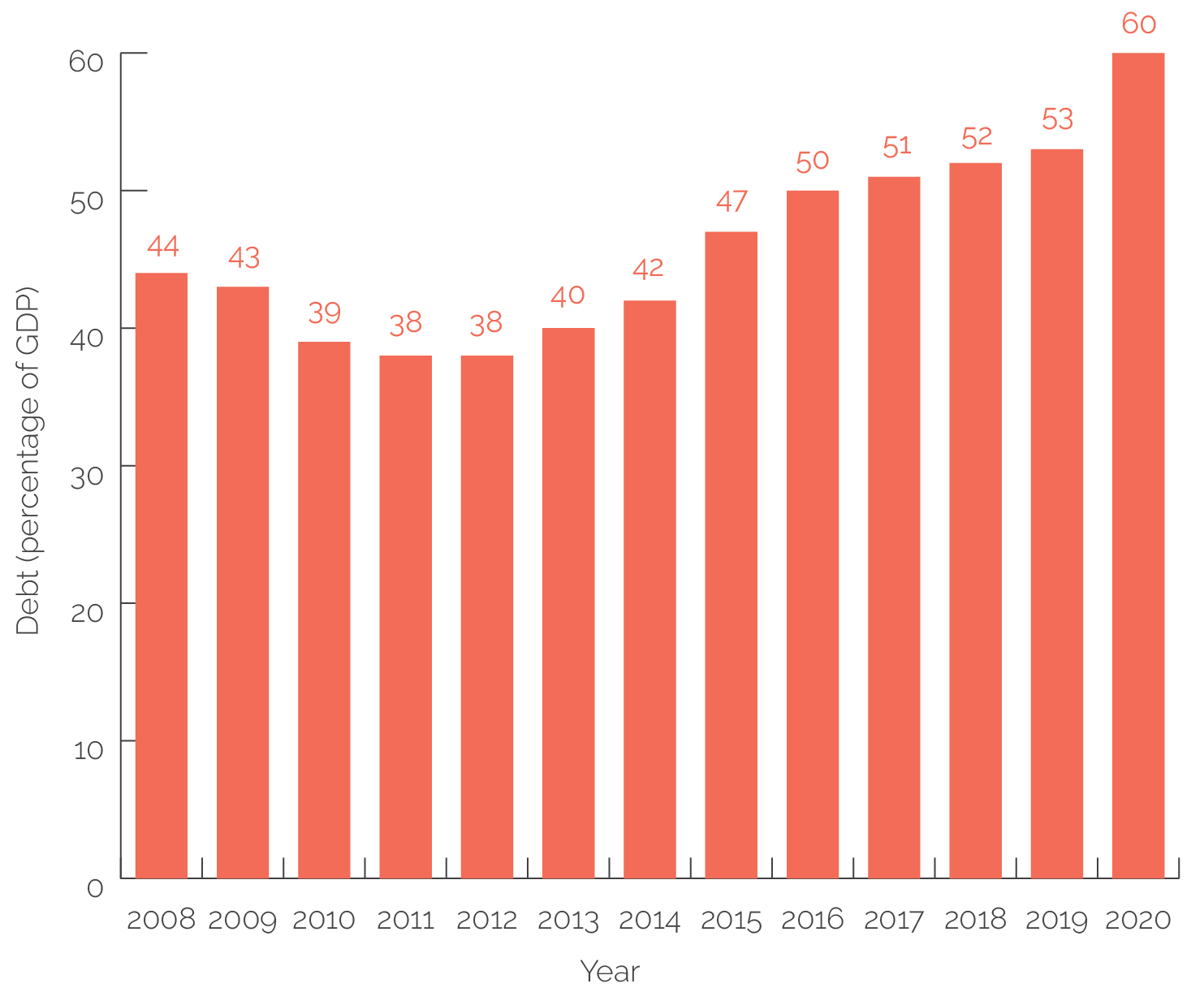

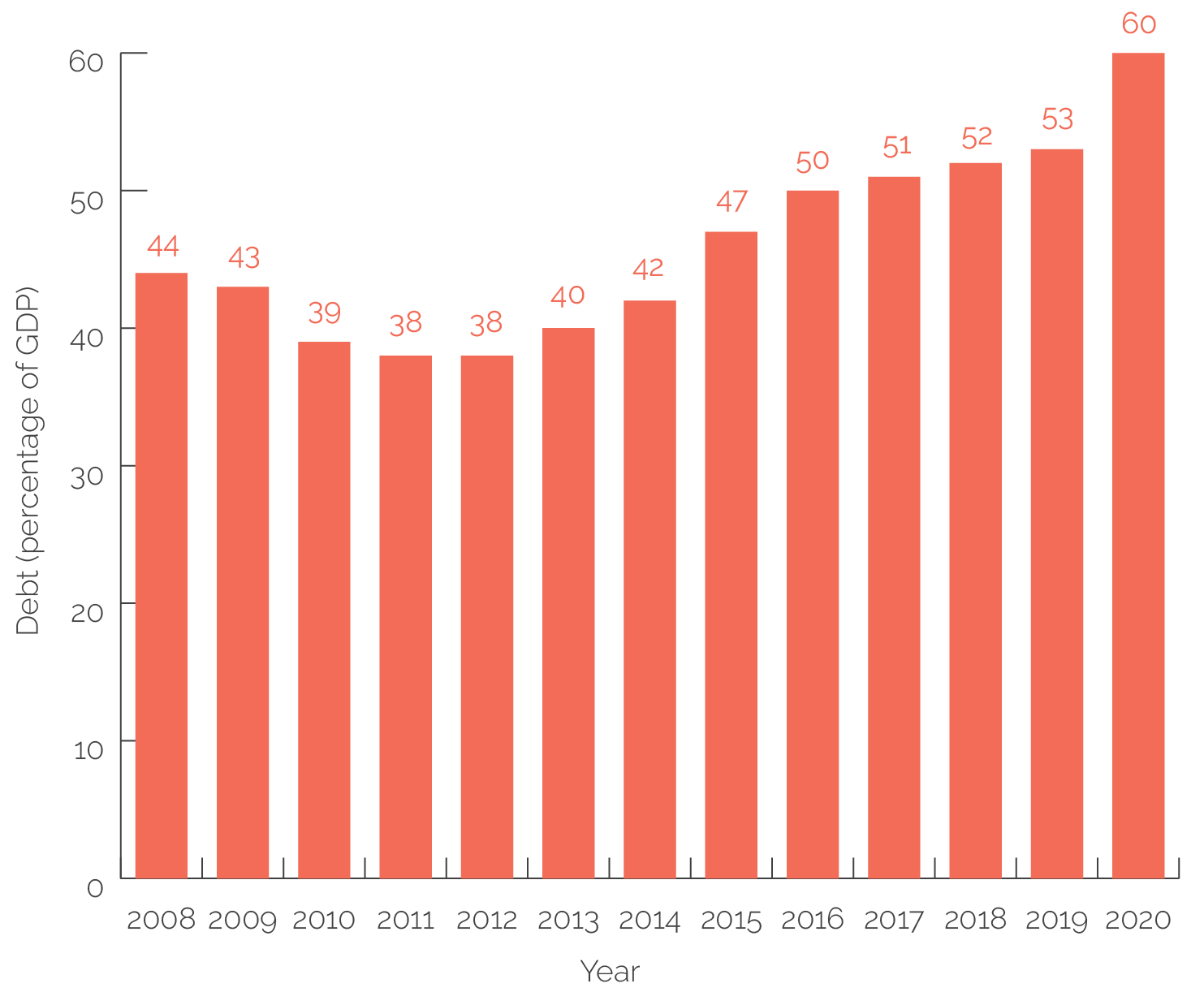

Figure 1.5. Public Debt as a Percentage of Gross Domestic Product for Low-Income Countries

Source: International Monetary Fund 2020b.

Note: The 2019 figures are preliminary; the 2020 figures are World Economic Outlook projections. GDP = gross domestic product.

In IDA-eligible countries, the average debt-to-GDP ratio increased from 44 percent in 2008 to 60 percent in 2020. The increase in general government gross debt-to-GDP ratios is less than that of IBRD countries (from 16 to 33 percent) over the same period. The average for the eight case study countries covered in this evaluation increased from 31 percent of GDP in 2008 to 42 percent in 2017; preliminary estimates for 2020 are 50 percent (table 1.2). This average, however, hides considerable variation across countries, from declines (Afghanistan and Bangladesh) to significant increases (all other countries), including to notably high levels in Ghana and Sierra Leone.

Table 1.2. Debt-to-Gross Domestic Product Ratio and Level of Debt Distress for Case Study Countries

|

Country |

Debt-to-GDP Ratio, General Government Gross Debt (percent) |

Level of Debt Distress |

||||

|

2008 |

2014 |

2020 est. |

2013 |

2018 |

||

|

Sierra Leonea |

42.4 |

35.1 |

77.4 |

High |

High |

|

|

Ghanaa |

24.9 |

51.2 |

76.7 |

High |

High |

|

|

Georgia |

30.3 |

33.3 |

58.7 |

(not LIC DSA assessed) |

||

|

Vietnam |

31.0 |

43.6 |

46.6 |

(not LIC DSA assessed) |

||

|

Burkina Fasoa |

23.0 |

26.6 |

46.6 |

Moderate |

Moderate |

|

|

Hondurasa |

22.3 |

37.1 |

46.0 |

Moderate |

Moderate |

|

|

Bangladesh |

40.6 |

35.3 |

39.6 |

Low |

Low |

|

|

Afghanistana |

19.1 |

8.7 |

7.8 |

High |

High |

|

|

Average |

30.7 |

42.0 |

49.9 |

— |

||

Source: Debt Management Monitor 2018; International Monetary Fund 2020b.

Note: DSA = debt sustainability analysis; est. = estimated; GDP = gross domestic product; LIC = low-income country. Countries listed in order of gross debt (percent).a. Heavily indebted poor countries.

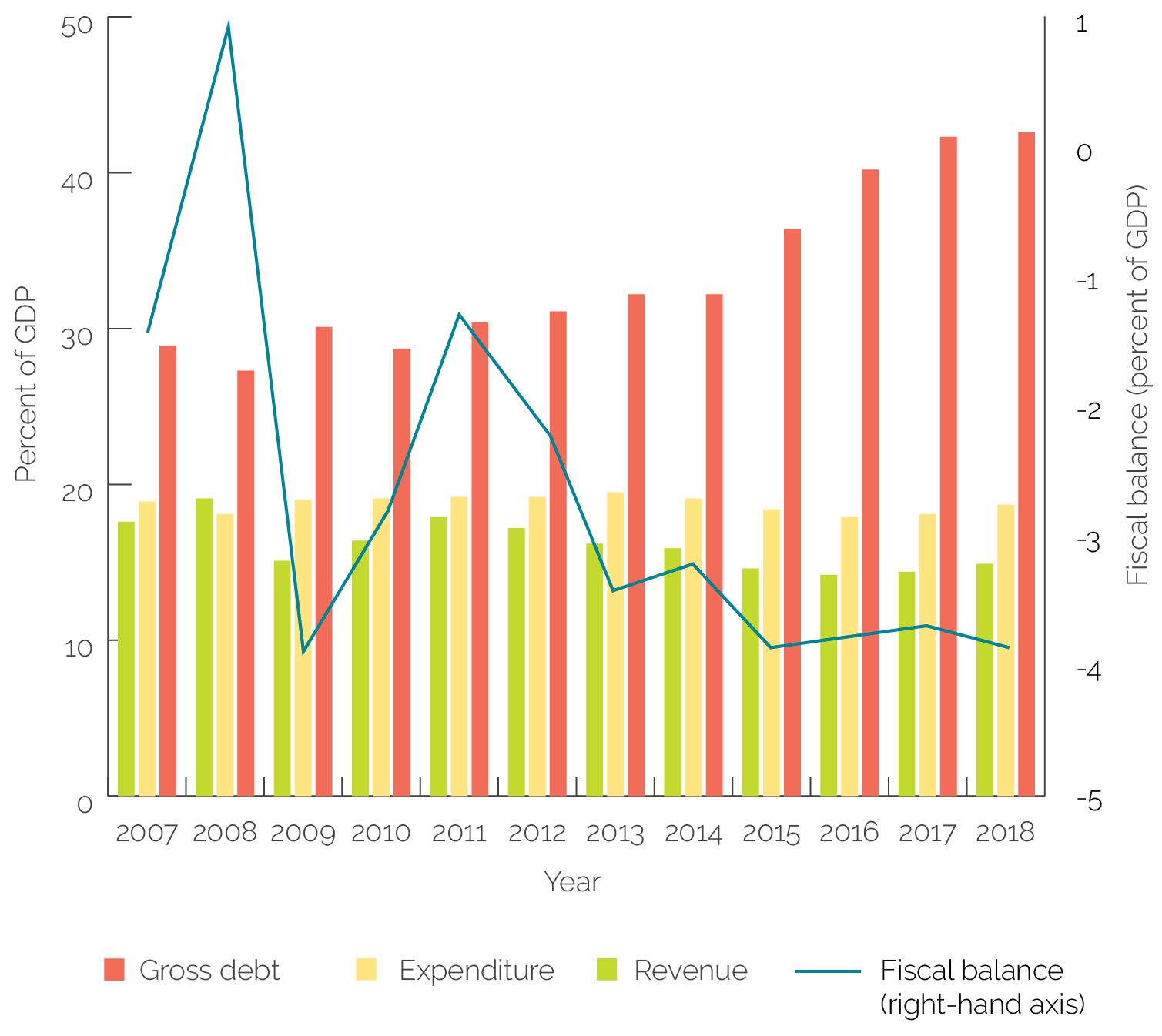

The worsening fiscal trend for IDA-eligible countries was particularly noticeable over the second half of the evaluation period (table 1.3). Figure 1.6 shows developments for revenue, expenditure, fiscal balance, and gross debt in relation to GDP for low-income countries. The sharp economic contraction and increase in financing needs due to COVID-19 will likely lead to a significant worsening of these indicators in 2020 and into 2021 for both low-income and middle-income countries.

Table 1.3. IDA-Eligible Countries—Fiscal Indicators (percent of GDP)

|

Indicator |

2007 |

2008 |

2009 |

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

|

Revenue |

18.3 |

19.8 |

15.8 |

17.0 |

18.8 |

18.0 |

16.7 |

16.5 |

15.1 |

14.7 |

14.9 |

15.4 |

|

Expenditure |

19.7 |

18.8 |

19.8 |

20.0 |

20.0 |

20.0 |

20.3 |

19.9 |

19.1 |

18.7 |

19.1 |

19.4 |

|

Fiscal balance |

−1.4 |

1.0 |

−4.0 |

−2.9 |

−1.3 |

−2.0 |

−3.5 |

−3.3 |

−3.9 |

−3.9 |

−4.2 |

−4.0 |

|

Gross debt |

30.1 |

28.6 |

31.7 |

29.9 |

31.5 |

31.8 |

32.9 |

33.7 |

37.7 |

41.3 |

43.7 |

45.0 |

Source: International Monetary Fund Fiscal Monitor database, April 2019.

Note: GDP = gross domestic product; IDA = International Development Association.

Figure 1.6. Low-Income Country Fiscal Indicators

Source: International Monetary Fund 2019a.

Note: GDP = gross domestic product.

- Public financial management (PFM) is itself an umbrella concept that, for the purposes of this evaluation, includes public expenditure management, which in turn includes public sector accounting, support for integrated financial management information systems, and public investment management.

- In 1983, the World Bank created its first organizational unit dedicated to research and operational support for administrative efficiency in government, the Public Sector Management Unit. This unit devoted much of its time to the restructuring of public enterprises, civil service reform, and PFM.

- The evaluation concluded, among other things, that procurement capacity building was disconnected from the World Bank’s broader support to public expenditure management: “Less successful have been efforts to mainstream procurement reform within the context of financial management reform and overall public expenditure management” (World Bank 2014a, 15).

- Although outside the scope of this evaluation, while establishing a clear relationship between strengthening PFM and achieving improved service delivery has proven elusive (see, for example, World Bank 2012a), there is growing momentum to rethink PFM support as a more “open” system that interacts fluidly with public policy and to better understand how PFM matters for service delivery (International Working Group 2020).

- Other exogenous shocks that affected the fiscal and debt outcomes of many International Development Association–eligible countries included the international oil and commodity price shock of 2014 and the Ebola outbreak in West Africa that same year.

- DMF: A 10-year Retrospective is available here: https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/387981607701888048/debt-management-facility-10-year-retrospective-2008-2018. Reports available here: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/debt/publication/strengthening-debt-management-capacity-in-low-and-middle-income-countries-an-assessment and https://www.imf.org/external/np/g20/pdf/2018/072718.pdf.. Reports available here: .

- The framework’s vision is to “strengthen debt management capacity in DMF-eligible countries to enable government to finance its public sector borrowing prudently with appropriate cost-risk mix, contribute to macro-economic stability and help support sustainable debt levels over the long term, and strengthen the framework for debt management to increase accountability, transparency and reporting.”

- Public financial management (PFM) is itself an umbrella concept that, for the purposes of this evaluation, includes public expenditure management, which in turn includes public sector accounting, support for integrated financial management information systems, and public investment management.

- In 1983, the World Bank created its first organizational unit dedicated to research and operational support for administrative efficiency in government, the Public Sector Management Unit. This unit devoted much of its time to the restructuring of public enterprises, civil service reform, and PFM.

- The evaluation concluded, among other things, that procurement capacity building was disconnected from the World Bank’s broader support to public expenditure management: “Less successful have been efforts to mainstream procurement reform within the context of financial management reform and overall public expenditure management” (World Bank 2014a, 15).