In 2007, after the inauguration of President Rafael Correa, the government of Ecuador canceled World Bank loans to the country, stopped all but one of its operations, and expelled the Bank country representative.

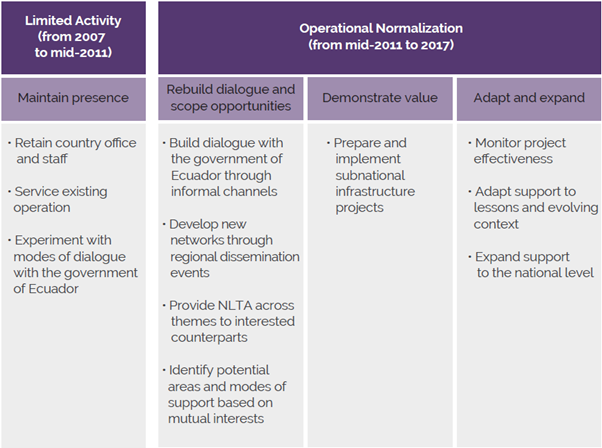

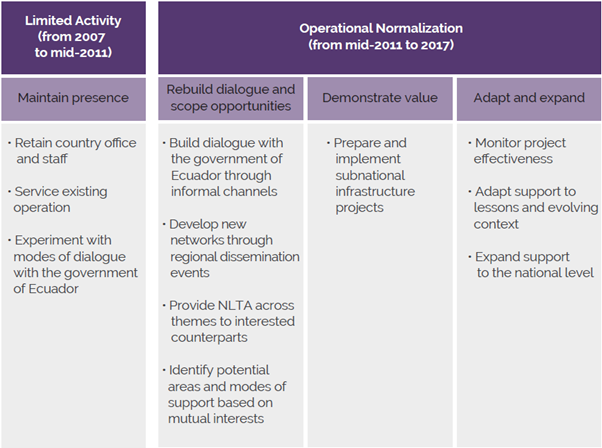

While International Finance Corporation activities were largely unaffected, the Bank faced the prospect of a complete collapse in relations. A new evaluation from the Independent Evaluation Group assesses the effectiveness of the World Bank Group’s engagement with Ecuador from 2008 to 2022 and traces Bank efforts to avoid a complete break in relations and rebuild the partnership. These efforts can be broken down into four stages:

Stage 1: Maintaining presence

The earliest efforts by the Bank from 2007 to mid-2011 were simple: to preserve a presence in Ecuador and prevent a more permanent disengagement. The Bank was effective in building goodwill and ensuring ties remained while respecting the government’s desire to limit the Bank’s visibility.

The Bank initially succeeded by maintaining a country office in Quito, arguing that it was necessary to service the remaining operation in Ecuador. A presence in the field allowed officials to assess developments, gradually rebuild dialogue with the government, and preserve open channels at the subnational level.

Step 2: Rebuild dialogue and scope opportunities

The Bank built on this limited platform to develop a more proactive role in Ecuador between mid-2011 and 2013.

First, the Bank increased its dialogue with the government by leveraging its expertise. It offered nonlending technical assistance and initiated analytic work on diverse topics, responded to requests across different sectors and levels of government, and increased its budget sixfold to support the heightened activity.

Second, the Bank experimented with different modes of dialogue with government. For example, in Quito in 2012, it hosted a launch event for a regional report on disability to showcase Ecuador’s efforts toward disability inclusion. Dialogue with subnational authorities on urban infrastructure ultimately paved the way for an eventual resumption of Bank lending directly to subnational authorities.

Step 3: Demonstrate value through subnational operations

Strengthened dialogue with subnational authorities led to a third stage in the Bank’s reengagement with the government of Ecuador: demonstrating its value to subnational authorities through infrastructure operations in transport and water.

Between 2014 and 2015, the Bank approved three investment operations (and initiated a fourth), directly to subnational or municipal authorities for infrastructure improvement. The first of these was the Quito metro project, for which the Bank cofinanced the construction of a universally accessible underground metro line. While the central government had no direct role, it provided a guarantee.

Step 4: Adapt and expand

Starting in 2016, the Bank strategy shifted to reestablishing investment operations at the national level. This strategy partly aimed to manage portfolio risks at a time of low implementation capacity for subnational projects low and many delays.

The shift also reflected a renewed openness by the central government to Bank finance as a result of a deteriorating macroeconomic environment and limited fiscal space. Between 2016 and 2017, the Bank delivered four national-level investment projects on education, disaster risk management, and agriculture.

The full rebuilding of the Bank’s scope of support in Ecuador (in particular through policy-based operations) did not take place until a change in government in mid-2017, when the new administration sought comprehensive support from the Bank for a new fiscally sustainable, private sector–led development model.

Key stages in World Bank reengagement decisions

Source: Independent Evaluation Group classification based on World Bank country program review.

Note: NLTA = nonlending technical assistance.

Lessons for reestablishing partnerships in challenging environments

The evaluation found that Bank Group projects over the reengagement period were generally effective, and Bank Group status in the country improved significantly. However, it also identified limitations to the Bank’s work, offering lessons for the future:

1. Balance responsiveness with due diligence in project preparation

Once relations with a country have been reestablished, it is tempting to deliver projects rapidly to demonstrate agility. But this should not compromise proper due diligence in project preparation. In some cases, rapid preparation came at the expense of quality engineering designs, resulting in substantial revisions during implementation and ultimately delaying public benefits and impact.

2. Build sufficient institutional capacity to mitigate risks

The evaluation found that Bank Group projects in the normalization period did not adequately account for constraints to the government’s institutional capacity. For example, the unit charged with the implementation of a project to improve public services in the city of Manta had no experience with Bank Group procedures, and project implementation was delayed by more than two and a half years. With a lapse in engagement (or with new borrowers), greater implementation support is required.

3. Stipulate higher-level outcomes

The Bank’s tentative position with the government meant it could not predict a five-year agenda of support in Ecuador between 2007 and 2017. This led to the Bank Group’s adoption of short-term (interim) strategies that did not include results frameworks stipulating higher-level objectives. This reduced accountability as well as the Bank Group’s ability to course correct to improve program performance. While the delicate relationship may have necessitated short-term strategies, the inclusion of higher-level results would have strengthened the line of sight between Bank Group support and high-level achievements.

Maintaining Bank Group support in an ever-changing world

In rare instances, transitions in political or economic circumstances can disrupt the Bank Group's relations with a host government, potentially leading to a halt in operations and, in the worst-case scenarios, a breakdown in dialogue.

In Ecuador, the Bank successfully rebuilt its partnership with the government from a severely constrained status by creating greater opportunities for dialogue, building goodwill, and demonstrating the World Bank’s value in politically acceptable ways.

Lessons from this experience can help Bank teams think through the relationship-rebuilding exercise, ensure knowledge is not lost during the interruption, and prepare to provide comprehensive support when adequate relations are restored.

Add new comment